Dobrovolsky, Leonard A.

Address: Scientific and Medical Information Department, Institute of Occupational Health, 75 Saksagansky Street, 252033 Kiev

Country: Ukraine

Phone: 44 220 6106

Fax: 44 220 6677

Past position(s): Student, Kiev Medical Institute; Deputy Head Physician of District Hospital, Chu Kazakhstan; Postgraduate (1957-1960), Junior and Senior Scientist, Lab. Radiology (1960-1968) of; Institute for Occupational Health, Kiev; Regional Officer for Occupational Health, World Health Organization, EURO, Copenhagen

Education: MD, 1955, Kiev Medical Institute; PhD, 1963, Institute for Occupational Health, Kiev; DSc, 1988, Institute for Occupational Health, Kiev

Areas of interest: Combined effects of ionizing and non-ionizing factors on the organism; safe use of pesticides; effects of high temperature; effects of heavy metals

Pesticides

Introduction

Human exposure to pesticides has different characteristics according to whether it occurs during industrial production or use (table 1). The formulation of commercial products (by mixing active ingredients with other coformulants) has some exposure characteristics in common with pesticide use in agriculture. In fact, since formulation is typically performed by small industries which manufacture many different products in successive operations, the workers are exposed to each of several pesticides for a short time. In public health and agriculture, the use of a variety of compounds is generally the rule, although in some specific applications (for example, cotton defoliation or malaria control programmes) a single product may be used.

Table 1. Comparison of exposure characteristics during production and use of pesticides

|

Exposure on production |

Exposure on use |

|

|

Duration of exposure |

Continuous and prolonged |

Variable and intermittent |

|

Degree of exposure |

Fairly constant |

Extremely variable |

|

Type of exposure |

To one or few compounds |

To numerous compounds either in sequence or concomitantly |

|

Skin absorption |

Easy to control |

Variable according to work procedures |

|

Ambient monitoring |

Useful |

Seldom informative |

|

Biological monitoring |

Complementary to ambient monitoring |

Very useful when available |

Source: WHO 1982a, modified.

The measurement of biological indicators of exposure is particularly useful for pesticide users where the conventional techniques of exposure assessment through ambient air monitoring are scarcely applicable. Most pesticides are lipid-soluble substances that penetrate the skin. The occurrence of percutaneous (skin) absorption makes the use of biological indicators very important in assessing the level of exposure in these circumstances.

Organophosphate Insecticides

Biological indicators of effect:

Cholinesterases are the target enzymes accounting for organophosphate (OP) toxicity to insect and mammalian species. There are two principal types of cholinesterases in the human organism: acetylcholinesterase (ACHE) and plasma cholinesterase (PCHE). OP causes toxic effects in humans through the inhibition of synaptic acetylcholinesterase in the nervous system. Acetylcholinesterase is also present in red blood cells, where its function is unknown. Plasma cholinesterase is a generic term covering an inhomogeneous group of enzymes present in glial cells, plasma, liver and some other organs. PCHE is inhibited by OPs, but its inhibition does not produce known functional derangements.

Inhibition of blood ACHE and PCHE activity is highly correlated with intensity and duration of OP exposure. Blood ACHE, being the same molecular target as that responsible for acute OP toxicity in the nervous system, is a more specific indicator than PCHE. However, sensitivity of blood ACHE and PCHE to OP inhibition varies among the individual OP compounds: at the same blood concentration, some inhibit more ACHE and others more PCHE.

A reasonable correlation exists between blood ACHE activity and the clinical signs of acute toxicity (table 2). The correlation tends to be better as the rate of inhibition is faster. When inhibition occurs slowly, as with chronic low-level exposures, the correlation with illness may be low or totally non-existent. It must be noted that blood ACHE inhibition is not predictive for chronic or delayed effects.

Table 2. Severity and prognosis of acute OP toxicity at different levels of ACHE inhibition

|

ACHE inhibition (%) |

Level of poisoning |

Clinical symptoms |

Prognosis |

|

50–60 |

Mild |

Weakness, headache, dizziness, nausea, salivation, lacrimation, miosis, moderate bronchial spasm |

Convalescence in 1-3 days |

|

60–90 |

Moderate |

Abrupt weakness, visual disturbance, excess salivation, sweating, vomiting, diarrhoea, bradycardia, hypertonia, tremors of hands and head, disturbed gait, miosis, pain in the chest, cyanosis of the mucous membranes |

Convalescence in 1-2 weeks |

|

90–100 |

Severe |

Abrupt tremor, generalized convulsions, psychic disturbance, intensive cyanosis, lung oedema, coma |

Death from respiratory or cardiac failure |

Variations of ACHE and PCHE activities have been observed in healthy people and in specific physiopathological conditions (table 3). Thus, the sensitivity of these tests in monitoring OP exposure can be increased by adopting individual pre-exposure values as a reference. Cholinesterase activities after exposure are then compared with the individual baseline values. One should make use of population cholinesterase activity reference values only when pre-exposure cholinesterase levels are not known (table 4).

Table 3. Variations of ACHE and PCHE activities in healthy people and in selected physiopathological conditions

|

Condition |

ACHE activity |

PCHE activity |

|

Healthy people |

||

|

Interindividual variation1 |

10–18 % |

15–25 % |

|

Intraindividual variation1 |

3–7 % |

6% |

|

Sex differences |

No |

10–15 % higher in male |

|

Age |

Reduced up to 6 months old |

|

|

Body mass |

Positive correlation |

|

|

Serum cholesterol |

Positive correlation |

|

|

Seasonal variation |

No |

No |

|

Circadian variation |

No |

No |

|

Menstruation |

Decreased |

|

|

Pregnancy |

Decreased |

|

|

Pathological conditions |

||

|

Reduced activity |

Leukaemia, neoplasm |

Liver disease; uraemia; cancer; heart failure; allergic reactions |

|

Increased activity |

Polycythaemia; thalassaemia; other congenital blood dyscrasias |

Hyperthyroidism; other conditions of high metabolic rate |

1 Source: Augustinsson 1955 and Gage 1967.

Table 4. Cholinesterase activities of healthy people without exposure to OP measured with selected methods

|

Method |

Sex |

ACHE* |

PCHE* |

|

Michel1 (DpH/h) |

male female |

0.77±0.08 0.75±0.08 |

0.95±0.19 0.82±0.19 |

|

Titrimetric1 (mmol/min ml) |

male/female |

13.2±0.31 |

4.90±0.02 |

|

Ellman’s modified2 (UI/ml) |

male female |

4.01±0.65 3.45±0.61 |

3.03±0.66 3.03±0.68 |

* mean result, ± standard deviation.

Source: 1 Laws 1991. 2 Alcini et al. 1988.

Blood should preferably be sampled within two hours after exposure. Venipuncture is preferred to extracting capillary blood from a finger or earlobe because the sampling point can be contaminated with pesticide residing on the skin in exposed subjects. Three sequential samples are recommended to establish a normal baseline for each worker before exposure (WHO 1982b).

Several analytical methods are available for the determination of blood ACHE and PCHE. According to WHO, the Ellman spectrophotometric method (Ellman et al. 1961) should serve as a reference method.

Biological indicators of exposure.

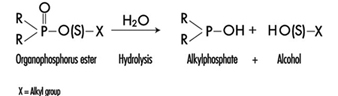

The determination in urine of metabolites that are derived from the alkyl phosphate moiety of the OP molecule or of the residues generated by the hydrolysis of the P–X bond (figure 1) has been used to monitor OP exposure.

Figure 1. Hydrolysis of OP insecticides

Alkyl phosphate metabolites.

The alkyl phosphate metabolites detectable in urine and the main parent compound from which they can originate are listed in table 5. Urinary alkyl phosphates are sensitive indicators of exposure to OP compounds: the excretion of these metabolites in urine is usually detectable at an exposure level at which plasma or erythrocyte cholinesterase inhibition cannot be detected. The urinary excretion of alkyl phosphates has been measured for different conditions of exposure and for various OP compounds (table 6). The existence of a relationship between external doses of OP and alkyl phosphate urinary concentrations has been established in a few studies. In some studies a significant relationship between cholinesterase activity and levels of alkyl phosphates in urine has also been demonstrated.

Table 5. Alkyl phosphates detectable in urine as metabolites of OP pesticides

|

Metabolite |

Abbreviation |

Principal parent compounds |

|

Monomethylphosphate |

MMP |

Malathion, parathion |

|

Dimethylphosphate |

DMP |

Dichlorvos, trichlorfon, mevinphos, malaoxon, dimethoate, fenchlorphos |

|

Diethylphosphate |

DEP |

Paraoxon, demeton-oxon, diazinon-oxon, dichlorfenthion |

|

Dimethylthiophosphate |

DMTP |

Fenitrothion, fenchlorphos, malathion, dimethoate |

|

Diethylthiophosphate |

DETP |

Diazinon, demethon, parathion,fenchlorphos |

|

Dimethyldithiophosphate |

DMDTP |

Malathion, dimethoate, azinphos-methyl |

|

Diethyldithiophosphate |

DEDTP |

Disulfoton, phorate |

|

Phenylphosphoric acid |

Leptophos, EPN |

Table 6. Examples of levels of urinary alkyl phosphates measured in various conditions of exposure to OP

|

Compound |

Condition of exposure |

Route of exposure |

Metabolite concentrations1 (mg/l) |

|

Parathion2 |

Nonfatal poisoning |

Oral |

DEP = 0.5 DETP = 3.9 |

|

Disulfoton2 |

Formulators |

Dermal/inhalation |

DEP = 0.01-4.40 DETP = 0.01-1.57 DEDTP = <0.01-.05 |

|

Phorate2 |

Formulators |

Dermal/inhalation |

DEP = 0.02-5.14 DETP = 0.08-4.08 DEDTP = <0.01-0.43 |

|

Malathion3 |

Sprayers |

Dermal |

DMDTP = <0.01 |

|

Fenitrothion3 |

Sprayers |

Dermal |

DMP = 0.01-0.42 DMTP = 0.02-0.49 |

|

Monocrotophos4 |

Sprayers |

Dermal/inhalation |

DMP = <0.04-6.3/24 h |

1 For abbreviations see table 27.12 [BMO12TE].

2 Dillon and Ho 1987.

3 Richter 1993.

4 van Sittert and Dumas 1990.

Alkyl phosphates are usually excreted in urine within a short time. Samples collected soon after the end of the workday are suitable for metabolite determination.

The measurement of alkyl phosphates in urine requires a rather sophisticated analytical method, based on derivatization of the compounds and detection by gas-liquid chromatography (Shafik et al. 1973a; Reid and Watts 1981).

Hydrolytic residues.

p-Nitrophenol (PNP) is the phenolic metabolite of parathion, methylparathion and ethyl parathion, EPN. The measurement of PNP in urine (Cranmer 1970) has been widely used and has proven to be successful in evaluating exposure to parathion. Urinary PNP correlates well with the absorbed dose of parathion. With PNP urinary levels up to 2 mg/l, the absorption of parathion does not cause symptoms, and little or no reduction of cholinesterase activities is observed. PNP excretion occurs rapidly and urinary levels of PNP become insignificant 48 hours after exposure. Thus, urine samples should be collected soon after exposure.

Carbamates

Biological indicators of effect.

Carbamate pesticides include insecticides, fungicides and herbicides. Insecticidal carbamate toxicity is due to the inhibition of synaptic ACHE, while other mechanisms of toxicity are involved for herbicidal and fungicidal carbamates. Thus, only exposure to carbamate insecticides can be monitored through the assay of cholinesterase activity in red blood cells (ACHE) or plasma (PCHE). ACHE is usually more sensitive to carbamate inhibitors than PCHE. Cholinergic symptoms have been usually observed in carbamate-exposed workers with a blood ACHE activity lower than 70% of the individual baseline level (WHO 1982a).

Inhibition of cholinesterases by carbamates is rapidly reversible. Therefore, false negative results can be obtained if too much time elapses between exposure and biological sampling or between sampling and analysis. In order to avoid such problems, it is recommended that blood samples be collected and analysed within four hours after exposure. Preference should be given to the analytical methods that allow the determination of cholinesterase activity immediately after blood sampling, as discussed for organophosphates.

Biological indicators of exposure.

The measurement of urinary excretion of carbamate metabolites as a method to monitor human exposure has so far been applied only to few compounds and in limited studies. Table 7 summarizes the relevant data. Since carbamates are promptly excreted in the urine, samples collected soon after the end of exposure are suitable for metabolite determination. Analytical methods for the measurements of carbamate metabolites in urine have been reported by Dawson et al. (1964); DeBernardinis and Wargin (1982) and Verberk et al. (1990).

Table 7. Levels of urinary carbamate metabolites measured in field studies

|

Compound |

Biological index |

Condition of exposure |

Environmental concentrations |

Results |

References |

|

Carbaryl |

a-naphthol a-naphthol a-naphthol |

formulators mixer/applicators unexposed population |

0.23–0.31 mg/m3 |

x=18.5 mg/l1 , max. excretion rate = 80 mg/day x=8.9 mg/l, range = 0.2–65 mg/l range = 1.5–4 mg/l |

WHO 1982a |

|

Pirimicarb |

metabolites I2 and V3 |

applicators |

range = 1–100 mg/l |

Verberk et al. 1990 |

1 Systemic poisonings have been occasionally reported.

2 2-dimethylamino-4-hydroxy-5,6-dimethylpyrimidine.

3 2-methylamino-4-hydroxy-5,6-dimethylpyrimidine.

x = standard deviation.

Dithiocarbamates

Biological indicators of exposure.

Dithiocarbamates (DTC) are widely used fungicides, chemically grouped in three classes: thiurams, dimethyldithiocarbamates and ethylene-bis-dithiocarbamates.

Carbon disulphide (CS2) and its main metabolite 2-thiothiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (TTCA) are metabolites common to almost all DTC. A significant increase in urinary concentrations of these compounds has been observed for different conditions of exposure and for various DTC pesticides. Ethylene thiourea (ETU) is an important urinary metabolite of ethylene-bis-dithiocarbamates. It may also be present as an impurity in market formulations. Since ETU has been determined to be a teratogen and a carcinogen in rats and in other species and has been associated with thyroid toxicity, it has been widely applied to monitor ethylene-bis-dithiocarbamate exposure. ETU is not compound-specific, as it may be derived from maneb, mancozeb or zineb.

Measurement of the metals present in the DTC has been proposed as an alternative approach in monitoring DTC exposure. Increased urinary excretion of manganese has been observed in workers exposed to mancozeb (table 8).

Table 8. Levels of urinary dithiocarbamate metabolites measured in field studies

|

Compound |

Biological index |

Condition of exposure |

Environmental concentrations* ± standard deviation |

Results ± standard deviation |

References |

|

Ziram |

Carbon disulphide (CS2) TTCA1 |

formulators formulators |

1.03 ± 0.62 mg/m3 |

3.80 ± 3.70 mg/l 0.45 ± 0.37 mg/l |

Maroni et al. 1992 |

|

Maneb/Mancozeb |

ETU2 |

applicators |

range = < 0.2–11.8 mg/l |

Kurttio et al. 1990 |

|

|

Mancozeb |

Manganese |

applicators |

57.2 mg/m3 |

pre-exposure: 0.32 ± 0.23 mg/g creatinine; post-exposure: 0.53 ± 0.34 mg/g creatinine |

Canossa et al. 1993 |

* Mean result according to Maroni et al. 1992.

1 TTCA = 2-thiothiazolidine-4-carbonylic acid.

2 ETU = ethylene thiourea.

CS2, TTCA, and manganese are commonly found in urine of non-exposed subjects. Thus, the measurement of urinary levels of these compounds prior to exposure is recommended. Urine samples should be collected in the morning following the cessation of exposure. Analytical methods for the measurements of CS2, TTCA and ETU have been reported by Maroni et al. (1992).

Synthetic Pyrethroids

Biological indicators of exposure.

Synthetic pyrethroids are insecticides similar to natural pyrethrins. Urinary metabolites suitable for application in biological monitoring of exposure have been identified through studies with human volunteers. The acidic metabolite 3-(2,2’-dichloro-vinyl)-2,2’-dimethyl-cyclopropane carboxylic acid (Cl2CA) is excreted both by subjects orally dosed with permethrin and cypermethrin and the bromo-analogue (Br2CA) by subjects treated with deltamethrin. In the volunteers treated with cypermethrin, a phenoxy metabolite, 4-hydroxy-phenoxy benzoic acid (4-HPBA), has also been identified. These tests, however, have not often been applied in monitoring occupational exposures because of the complex analytical techniques required (Eadsforth, Bragt and van Sittert 1988; Kolmodin-Hedman, Swensson and Akerblom 1982). In applicators exposed to cypermethrin, urinary levels of Cl2CA have been found to range from 0.05 to 0.18 mg/l, while in formulators exposed to a-cypermethrin, urinary levels of 4-HPBA have been found to be lower than 0.02 mg/l.

A 24-hour urine collection period started after the end of exposure is recommended for metabolite determinations.

Organochlorines

Biological indicators of exposure.

Organochlorine (OC) insecticides were widely used in the 1950s and 1960s. Subsequently, the use of many of these compounds was discontinued in many countries because of their persistence and consequent contamination of the environment.

Biological monitoring of OC exposure can be carried out through the determination of intact pesticides or their metabolites in blood or serum (Dale, Curley and Cueto 1966; Barquet, Morgade and Pfaffenberger 1981). After absorption, aldrin is rapidly metabolized to dieldrin and can be measured as dieldrin in blood. Endrin has a very short half-life in blood. Therefore, endrin blood concentration is of use only in determining recent exposure levels. The determination of the urinary metabolite anti-12-hydroxy-endrin has also proven to be useful in monitoring endrin exposure (van Sittert and Tordoir 1987) .

Significant correlations between the concentration of biological indicators and the onset of toxic effects have been demonstrated for some OC compounds. Instances of toxicity due to aldrin and dieldrin exposure have been related to levels of dieldrin in blood above 200 μg/l. A blood lindane concentration of 20 μg/l has been indicated as the upper critical level as far as neurological signs and symptoms are concerned. No acute adverse effects have been reported in workers with blood endrin concentrations below 50 μg/l. Absence of early adverse effects (induction of liver microsomal enzymes) has been shown on repeated exposures to endrin at urinary anti-12-hydroxy-endrin concentrations below 130 μg/g creatinine and on repeated exposures to DDT at DDT or DDE serum concentrations below 250 μg/l.

OC may be found in low concentrations in the blood or urine of the general population. Examples of observed values are as follows: lindane blood concentrations up to 1 μg/l, dieldrin up to 10 μg/l, DDT or DDE up to 100 μg/l, and anti-12-hydroxy-endrin up to 1 μg/g creatinine. Thus, a baseline assessment prior to exposure is recommended.

For exposed subjects, blood samples should be taken immediately after the end of a single exposure. For conditions of long-term exposure, the time of collection of the blood sample is not critical. Urine spot samples for urinary metabolite determination should be collected at the end of exposure.

Triazines

Biological indicators of exposure.

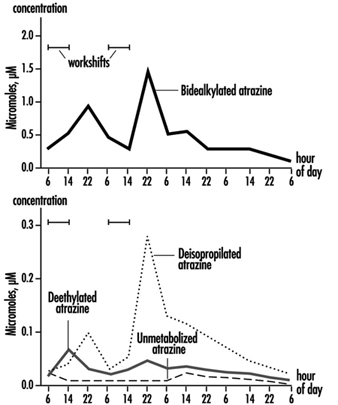

The measurement of urinary excretion of triazinic metabolites and the unmodified parent compound has been applied to subjects exposed to atrazine in limited studies. Figure 2 shows the urinary excretion profiles of atrazine metabolites of a manufacturing worker with dermal exposure to atrazine ranging from 174 to 275 μmol/workshift (Catenacci et al. 1993). Since other chlorotriazines (simazine, propazine, terbuthylazine) follow the same biotransformation pathway of atrazine, levels of dealkylated triazinic metabolites may be determined to monitor exposure to all chlorotriazine herbicides.

Figure 2. Urinary excretion profiles of atrazine metabolites

The determination of unmodified compounds in urine may be useful as a qualitative confirmation of the nature of the compound that has generated the exposure. A 24–hour urine collection period started at the beginning of exposure is recommended for metabolite determination.

Recently, by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA test), a mercapturic acid conjugate of atrazine has been identified as its major urinary metabolite in exposed workers. This compound has been found in concentrations at least 10 times higher than those of any dealkylated products. A relationship between cumulative dermal and inhalation exposure and total amount of the mercapturic acid conjugate excreted over a 10-day period has been observed (Lucas et al. 1993).

Coumarin Derivatives

Biological indicators of effect.

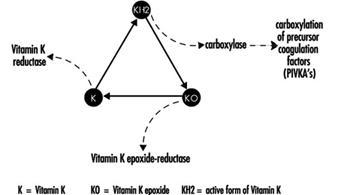

Coumarin rodenticides inhibit the activity of the enzymes of the vitamin K cycle in the liver of mammals, humans included (figure 3), thus causing a dose-related reduction of the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors, namely factor II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X. Anticoagulant effects appear when plasma levels of clotting factors have dropped below approximately 20% of normal.

Figure 3. Vitamin K cycle

These vitamin K antagonists have been grouped into so-called “first generation” (e.g., warfarin) and “second generation” compounds (e.g., brodifacoum, difenacoum), the latter characterized by a very long biological half-life (100 to 200 days).

The determination of prothrombin time is widely used in monitoring exposure to coumarins. However, this test is sensitive only to a clotting factor decrease of approximately 20% of normal plasma levels. The test is not suitable for detection of early effects of exposure. For this purpose, the determination of the prothrombin concentration in plasma is recommended.

In the future, these tests might be replaced by the determination of coagulation factor precursors (PIVKA), which are substances detectable in blood only in the case of blockage of the vitamin K cycle by coumarins.

With conditions of prolonged exposure, the time of blood collection is not critical. In cases of acute overexposure, biological monitoring should be carried out for at least five days after the event, in view of the latency of the anticoagulant effect. To increase the sensitivity of these tests, the measurement of baseline values prior to exposure is recommended.

Biological indicators of exposure.

The measurement of unmodified coumarins in blood has been proposed as a test to monitor human exposure. However, experience in applying these indices is very limited mainly because the analytical techniques are much more complex (and less standardized) in comparison with those required to monitor the effects on the coagulation system (Chalermchaikit, Felice and Murphy 1993).

Phenoxy Herbicides

Biological indicators of exposure.

Phenoxy herbicides are scarcely biotransformed in mammals. In humans, more than 95% of a 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) dose is excreted unchanged in urine within five days, and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T) and 4-chloro-2-methylphenoxyacetic acid (MCPA) are also excreted mostly unchanged via urine within a few days after oral absorption. The measurement of unchanged compounds in urine has been applied in monitoring occupational exposure to these herbicides. In field studies, urinary levels of exposed workers have been found to range from 0.10 to 8 μg/l for 2,4-D, from 0.05 to 4.5 μg/l for 2,4,5-T and from below 0.1 μg/l to 15 μg/l for MCPA. A 24-hour period of urine collection starting at the end of exposure is recommended for the determination of unchanged compounds. Analytical methods for the measurements of phenoxy herbicides in urine have been reported by Draper (1982).

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds

Biological indicators of exposure.

Diquat and paraquat are herbicides scarcely biotransformed by the human organism. Because of their high water solubility, they are readily excreted unchanged in urine. Urine concentrations below the analytical detection limit (0.01 μg/l) have been often observed in paraquat exposed workers; while in tropical countries, concentrations up to 0.73 μg/l have been measured after improper paraquat handling. Urinary diquat concentrations lower than the analytical detection limit (0.047 μg/l) have been reported for subjects with dermal exposures from 0.17 to 1.82 μg/h and inhalation exposures lower than 0.01 μg/h. Ideally, 24 hours sampling of urine collected at the end of exposure should be used for analysis. When this is impractical, a spot sample at the end of the workday can be used.

Determination of paraquat levels in serum is useful for prognostic purposes in case of acute poisoning: patients with serum paraquat levels up to 0.1 μg/l twenty-four hours after ingestion are likely to survive.

The analytical methods for paraquat and diquat determination have been reviewed by Summers (1980).

Miscellaneous Pesticides

4,6-Dinitro-o-cresol (DNOC).

DNOC is an herbicide introduced in 1925, but the use of this compound has been progressively decreased due to its high toxicity to plants and to humans. Since blood DNOC concentrations correlate to a certain extent with the severity of adverse health effects, the measure of unchanged DNOC in blood has been proposed for monitoring occupational exposures and for the evaluation of the clinical course of poisonings.

Pentachlorophenol.

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) is a wide-spectrum biocide with pesticidal action against weeds, insects, and fungi. Measurements of blood or urinary unchanged PCP have been recommended as suitable indices in monitoring occupational exposures (Colosio et al. 1993), because these parameters are significantly correlated with PCP body burden. In workers with prolonged exposure to PCP the time of blood collection is not critical, while urine spot samples should be collected on the morning after exposure.

A multiresidue method for the measurement of halogenated and nitrophenolic pesticides has been described by Shafik et al.(1973b).

Other tests proposed for the biological monitoring of pesticide exposure are listed in table 9.

Table 9. Other indices proposed in the literature for the biological monitoring of pesticide exposure

|

Compound |

Biological index |

|

|

Urine |

Blood |

|

|

Bromophos |

Bromophos |

Bromophos |

|

Captan |

Tetrahydrophtalimide |

|

|

Carbofuran |

3-Hydroxycarbofuran |

|

|

Chlordimeform |

4-Chloro-o-toluidine derivatives |

|

|

Chlorobenzilate |

p,p-1-Dichlorobenzophenone |

|

|

Dichloropropene |

Mercapturic acid metabolites |

|

|

Fenitrothion |

p-Nitrocresol |

|

|

Ferbam |

Thiram |

|

|

Fluazifop-Butyl |

Fluazifop |

|

|

Flufenoxuron |

Flufenoxuron |

|

|

Glyphosate |

Glyphosate |

|

|

Malathion |

Malathion |

Malathion |

|

Organotin compounds |

Tin |

Tin |

|

Trifenomorph |

Morpholine, triphenylcarbinol |

|

|

Ziram |

Thiram |

|

Conclusions

Biological indicators for monitoring pesticide exposure have been applied in a number of experimental and field studies.

Some tests, such as those for cholinesterase in blood or for selected unmodified pesticides in urine or blood, have been validated by extensive experience. Biological exposure limits have been proposed for these tests (table 10). Other tests, in particular those for blood or urinary metabolites, suffer from greater limitations because of analytical difficulties or because of limitations in interpretation of results.

Table 10. Recommended biological limit values (as of 1996)

|

Compound |

Biological index |

BEI1 |

BAT2 |

HBBL3 |

BLV4 |

|

ACHE inhibitors |

ACHE in blood |

70% |

70% |

70%, |

|

|

DNOC |

DNOC in blood |

20 mg/l, |

|||

|

Lindane |

Lindane in blood |

0.02mg/l |

0.02mg/l |

||

|

Parathion |

PNP in urine |

0.5mg/l |

0.5mg/l |

||

|

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) |

PCP in urine PCP in plasma |

2 mg/l 5 mg/l |

0.3mg/l 1 mg/l |

||

|

Dieldrin/Aldrin |

Dieldrin in blood |

100 mg/l |

|||

|

Endrin |

Anti-12-hydroxy-endrin in urine |

130 mg/l |

|||

|

DDT |

DDT and DDEin serum |

250 mg/l |

|||

|

Coumarins |

Prothrombin time in plasma Prothrombin concentration in plasma |

10% above baseline 60% of baseline |

|||

|

MCPA |

MCPA in urine |

0.5 mg/l |

|||

|

2,4-D |

2,4-D in urine |

0.5 mg/l |

1 Biological exposure indices (BEIs) are recommended by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH 1995).

2 Biological tolerance values (BATs) are recommended by the German Commission for the Investigation of Health Hazards of Chemical Compounds in the Work Area (DFG 1992).

3 Health-based biological limits (HBBLs) are recommended by a WHO Study Group (WHO 1982a).

4 Biological limit values (BLVs) are proposed by a Study Group of the Scientific Committee on Pesticides of the International Commission on Occupational Health (Tordoir et al. 1994). Assessment of working conditions is called for if this value is exceeded.

This field is in rapid development and, given the enormous importance of using biological indicators to assess exposure to these substances, new tests will be continuously developed and validated.

Occupational Health and Safety Measures in Agricultural Areas Contaminated by Radionuclides: The Chernobyl Experience

Massive contamination of agricultural lands by radionuclides occurs, as a rule, due to large accidents at the enterprises of nuclear industry or nuclear power stations. Such accidents occurred at Windscale (England) and South Ural (Russia). The largest accident happened in April 1986 at the Chernobyl nuclear power station. The latter entailed intensive contamination of soils over several thousands of square kilometres.

The major factors contributing to radiation effects in agricultural areas are as follows:

- whether radiation is from a single or a long-term exposure

- total quantity of radioactive substances entering the environment

- ratio of radionuclides in the fallout

- distance from the source of radiation to agricultural lands and settlements

- hydrogeological and soil characteristics of agricultural lands and the purpose of their use

- peculiarities of work of the rural population; diet, water supply

- time since the radiological accident.

As a result of the Chernobyl accident more than 50 million Curies (Ci) of mostly volatile radionuclides entered the environment. At the first stage, which covered 2.5 months (the “iodine period”), iodine-131 produced the greatest biological hazard, with significant doses of high-energy gamma radiation.

Work on agricultural lands during the iodine period should be strictly regulated. Iodine-131 accumulates in the thyroid gland and damages it. After the Chernobyl accident, a zone of very high radiation intensity, where no one was permitted to live or work, was defined by a 30 km radius around the station.

Outside this prohibited zone, four zones with various rates of gamma radiation on the soils were distinguished according to which types of agricultural work could be performed; during the iodine period, the four zones had the following radiation levels measured in roentgen (R):

- zone 1—less than 0.1 mR/h

- zone 2—0.1 to 1 mR/h

- zone 3—1.0 to 5 mR/h

- zone 4—5 mR/h and more.

Actually, due to the “spot” contamination by radionuclides over the iodine period, agricultural work in these zones was performed at levels of gamma irradiation from 0.2 to 25 mR/h. Apart from uneven contamination, variation in gamma radiation levels was caused by different concentrations of radionuclides in different crops. Forage crops in particular are exposed to high levels of gamma emitters during harvesting, transportation, ensilage and when they are used as fodder.

After the decay of iodine-131, the major hazard for agricultural workers is presented by the long-lived nuclides caesium-137 and strontium-90. Caesium-137, a gamma emitter, is a chemical analogue of potassium; its intake by humans or animals results in uniform distribution throughout the body and it is relatively quickly excreted with urine and faeces. Thus, the manure in the contaminated areas is an additional source of radiation and it must be removed as quickly as possible from stock farms and stored in special sites.

Strontium-90, a beta emitter, is a chemical analogue of calcium; it is deposited in bone marrow in humans and animals. Strontium-90 and caesium-137 can enter the human body through contaminated milk, meat or vegetables.

The division of agricultural lands into zones after the decay of short-lived radionuclides is carried out according to a different principle. Here, it is not the level of gamma radiation, but the amount of soil contamination by caesium-137, strontium-90 and plutonium-239 that are taken into account.

In the case of particularly severe contamination, the population is evacuated from such areas and farm work is performed on a 2-week rotation schedule. The criteria for zone demarcation in the contaminated areas are given in table 1.

Table 1. Criteria for contamination zones

|

Contamination zones |

Soil contamination limits |

Dosage limits |

Type of action |

|

1. 30 km zone |

– |

– |

Residing of |

|

2. Unconditional |

15 (Ci)/km2 |

0.5 cSv/year |

Agricultural work is performed with 2-week rotation schedule under strict radiological control. |

|

3. Voluntary |

5–15 Ci/km2 |

0.01–0.5 |

Measures are undertaken to reduce |

|

4. Radio- ecological |

1–5 Ci/km2 |

0.01 cSv/year |

Agricultural work is |

When people work on agricultural lands contaminated by radionuclides, the intake of radionuclides by the body through respiration and contact with soil and vegetable dusts may occur. Here, both beta emitters (strontium-90) and alpha emitters are extremely dangerous.

As a result of accidents at nuclear power stations, part of radioactive materials entering the environment are low-dispersed, highly active particles of the reactor fuel—“hot particles”.

Considerable amounts of dust containing hot particles are generated during agricultural work and in windy periods. This was confirmed by the results of investigations of tractor air filters taken from machines which were operated on the contaminated lands.

The assessment of dose loads on the lungs of agricultural workers exposed to hot particles revealed that outside the 30 km zone the doses amounted to several millisieverts (Loshchilov et al. 1993).

According to the data of Bruk et al. (1989) the total activity of caesium-137 and caesium-134 in the inspired dust in machine operators amounted to 0.005 to 1.5 nCi/m3. According to their calculations, over the total period of field work the effective dose to lungs ranged from 2 to

70 cSv.

The relation between the amount of soil contamination by caesium-137 and radioactivity of work zone air was established. According to the data of the Kiev Institute for Occupational Health it was found that when the soil contamination by caesium-137 amounted to 7.0 to 30.0 Ci/km2 the radioactivity of the breathing zone air reached 13.0 Bq/m3. In the control area, where the density of contamination amounted to 0.23 to 0.61 Ci/km3, the radioactivity of work zone air ranged from 0.1 to 1.0 Bq/m3 (Krasnyuk, Chernyuk and Stezhka 1993).

The medical examinations of agricultural machine operators in the “clear” and contaminated zones revealed an increase in cardiovascular diseases in workers in the contaminated zones, in the form of ischaemic heart disease and neurocirculatory dystonia. Among other disorders dysplasia of the thyroid gland and an increased level of monocytes in the blood were registered more frequently.

Hygienic Requirements

Work schedules

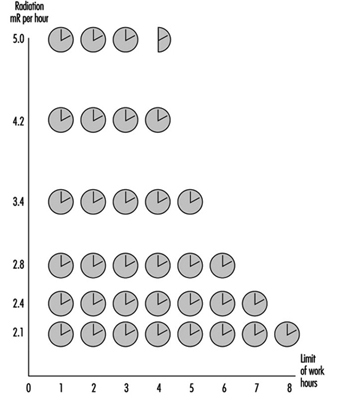

After large accidents at nuclear power stations, temporary regulations for the population are usually adopted. After the Chernobyl accident temporary regulations for a period of one year were adopted, with the TLV of 10 cSv. It is assumed that workers receive 50% of their dose due to external radiation during work. Here, the threshold of intensity of radiation dose over the eight-hour work day should not exceed 2.1 mR/h.

During agricultural work, the radiation levels at workplaces can fluctuate significantly, depending on the concentrations of radioactive substances in soils and plants; they also fluctuate during technological processing (siloing, preparation of dry fodder and so on). In order to reduce dosages to workers, regulations of time limits for agricultural work are introduced. Figure 1 shows regulations which were introduced after the Chernobyl accident.

Figure 1. Time limits for agricultural work depending on intensity of gamma-ray radiation at workplaces.

Agrotechnologies

When carrying out agricultural work in conditions of high contamination of soils and plants, it is necessary to strictly observe measures directed at prevention of dust contamination. The loading and unloading of dry and dusty substances should be mechanized; the neck of the conveyer tube should be covered with fabric. Measures directed at the decrease of dust release must be undertaken for all types of field work.

Work using agricultural machinery should be carried out taking due account of cabin pressurization and the choice of the proper direction of operation, with the wind at the side being preferable. If possible it is desirable to first water the areas being cultivated. The wide use of industrial technologies is recommended so as to eliminate manual work on the fields as much as possible.

It is appropriate to apply substances to the soils which can promote absorption and fixation of radionuclides, changing them into insoluble compounds and thus preventing the transfer of radionuclides into plants.

Agricultural machinery

One of the major hazards for the workers is agricultural machinery contaminated by radionuclides. The allowable work time on the machines depends on the intensity of gamma radiation emitted from the cabin surfaces. Not only is the thorough pressurization of cabins required, but due control over ventilation and air conditioning systems as well. After work, wet cleaning of cabins and replacement of filters should be carried out.

When maintaining and repairing the machines after decontamination procedures, the intensity of gamma radiation at the outer surfaces should not exceed 0.3 mR/h.

Buildings

Routine wet cleaning should be done inside and outside buildings. Buildings should be equipped with showers. When preparing fodder which contains dust components, it is necessary to adhere to procedures aimed at prevention of dust intake by the workers, as well as to keep the dust off the floor, equipment and so on.

Pressurization of the equipment should be under control. Workplaces should be equipped with effective general ventilation.

Use of pesticides and mineral fertilizers

The application of dust and granular pesticides and mineral fertilizers, as well as spraying from aeroplanes, should be restricted. Machine spraying and application of granular chemicals as well as liquid mixed fertilizers are preferable. The dust mineral fertilizers should be stored and transported only in tightly closed containers.

Loading and unloading work, preparation of pesticide solutions and other activities should be performed using maximum individual protective equipment (overalls, helmets, goggles, respirators, rubber gauntlets and boots).

Water supply and diet

There should be special closed premises or motor vans without draughts where workers can take their meals. Before taking meals workers should clean their clothes and thoroughly wash their hands and faces with soap and running water. During summer periods field workers should be supplied with drinking water. The water should be kept in closed containers. Dust must not enter containers when filling them with water.

Preventive medical examinations of workers

Periodic medical examinations should be carried out by a physician; laboratory analysis of blood, ECG and tests of respiratory function are compulsory. Where radiation levels do not exceed permissible limits, the frequency of medical examinations should be not less than once every 12 months. Where there are higher levels of ionizing radiation the examinations should be carried out more frequently (after sowing, harvesting and so on) with due account of radiation intensity at workplaces and the total absorbed dose.

Organization of Radiological Control over Agricultural Areas

The major indices characterizing the radiological situation after fallout are gamma radiation intensity in the area, contamination of agricultural lands by the selected radionuclides and content of radionuclides in agricultural products.

The determination of gamma radiation levels in the areas allows the drawing of the borders of severely contaminated areas, estimation of doses of external radiation to people engaged in agricultural work and the establishing of corresponding schedules providing for radiological safety.

The functions of radiological monitoring in agriculture are usually the responsibility of radiological laboratories of the sanitary service as well as veterinary and agrochemical radiological laboratories. The training and education of the personnel engaged in dosimetric control and consultations for the rural population are carried out by these laboratories.

Pesticides

Adapted from 3rd edition, Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. Revision includes information from A. Baiinova, J.F. Copplestone, L.A. Dobrobolskij,

F. Kaloyanova-Simeonova, Y.I. Kundiev and A.M. Shenker.

The word pesticide generally denotes a chemical substance (which may be mixed with other substances) that is used for the destruction of an organism deemed to be detrimental to humans. The word clearly has a very wide meaning and includes a number of other terms, such as insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, rodenticides, bactericides, miticides, nematocides and molluscicides, which individually indicate the organisms or pests that the chemical or class of chemicals is designed to kill. As different types of chemical agents are used for these general classes, it is usually advisable to indicate the particular category of pesticide.

General Principles

Acute toxicity is measured by the LD50 value; this is a statistical estimate of the number of mg of the chemical per kg of body weight required to kill 50% of a large population of test animals. The dose may be administered by a number of routes, usually orally or dermally, and the rat is the standard test animal. Oral or dermal LD50 values are used according to which route has the lower value for a specific chemical. Other effects, either as a result of short-term exposure (such as neurotoxicity or mutagenicity) or of long-term exposure (such as carcinogenicity), have to be taken into account, but pesticides with such known properties are not registered for use. The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 1996-1997 issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies technical products according to the acute risk to human health as follows:

- Class IA—extremely hazardous

- Class IB—highly hazardous

- Class II—moderately hazardous

- Class III—slightly hazardous.

The guidelines based on the WHO Classification list pesticides according to toxicity and physical state; these are presented in a separate article in this chapter.

Poisons enter the body through the mouth (ingestion), the lungs (inhalation), the intact skin (percutaneous absorption) or wounds in the skin (inoculation). The inhalation hazard is determined by the physical form and solubility of the chemical. The possibility and degree of percutaneous absorption varies with the chemical. Some chemicals also exert a direct action on the skin, causing dermatitis. Pesticides are applied in many different forms—as solids, by spraying in dilute or concentrated form, as dusts (fine or granulated), and as fogs and gases. The method of use has a bearing on the likelihood of absorption.

The chemical may be mixed with solids (often with food used as bait), water, kerosene, oils or organic solvents. Some of these diluents have some degree of toxicity of their own and may influence the rate of absorption of the pesticide chemical. Many formulations contain other chemicals which are not themselves pesticides but which enhance the effectiveness of the pesticide. Added surface-active agents are a case in point. When two or more pesticides are mixed in the same formulation, the action of one or both may be enhanced by the presence of the other. In many cases, the combined effects of mixtures have not been fully worked out, and it is a good rule that mixtures should always be treated as more toxic than any of the constituents on their own.

By their very nature and purpose, pesticides have adverse biological effects on at least some species, human beings included. The following discussion provides a broad overview of the mechanisms by which pesticides can act, and some of their toxic effects. Carcinogenicity, biological monitoring and safeguards in the use of pesticides are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.

Organochlorine Pesticides

The organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) have caused intoxication following skin contact, ingestion or inhalation. Examples are endrin, aldrin and dieldrin. The rate of absorption and toxicity differ depending on the chemical structure and the solvents, surfactants and emulsifiers used in the formulation.

The elimination of OCPs from the body takes place slowly through the kidneys. Metabolism in the cells involves various mechanisms—oxidation, hydrolysis and others. OCPs have a strong tendency to penetrate cell membranes and to be stored in the body fat. Because of their attraction to fatty tissues (lipotropic properties) OCPs tend to be stored in the central nervous system (CNS), liver, kidneys and the myocardium. In these organs they cause damage to the function of important enzyme systems and disrupt the biochemical activity of the cells.

OCPs are highly lipophilic and tend to accumulate in fatty tissue as long as exposure persists. When exposure ceases, they are released slowly into the bloodstream, often over a period of many years, from whence they can be transported to other organs where genotoxic effects, including cancer, may be initiated. The great majority of US residents, for example, have detectable levels of organochlorine pesticides, including breakdown products of DDT, in their adipose (fatty) tissue, and the concentrations increase with age, reflecting lifetime accumulations.

A number of OCPs that have been used throughout the world as insecticides and herbicides are also proven or suspected carcinogens to humans. These are discussed in more detail in the Toxicology and Cancer chapters of this Encyclopaedia.

Acute intoxications

Aldrin, endrin, dieldrin and toxaphene are most frequently implicated in acute poisoning. Delay in the onset of symptoms in severely acute intoxications is about 30 minutes. With lower toxicity OCPs it is several hours but not more than twelve.

Intoxication is demonstrated by gastrointestinal symptoms: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and stomach pains. The basic syndrome is cerebral: headache, dizziness, ataxia and paraesthesia. Gradually tremors set in, starting from the eyelids and the face muscles, descending towards the whole body and the limbs; in severe cases this leads to fits of tonic-clonic convulsions, which gradually extend to the different muscle groups. Convulsions may be connected with elevated body temperature and unconsciousness and may result in death. In addition to the cerebral signs, acute intoxications may lead to bulbar paralysis of the respiratory and/or vasomotor centres, which causes acute respiratory deficiency or apnoea, and to severe collapse.

Many patients develop signs of toxic hepatitis and toxic nephropathy. After these symptoms have disappeared some patients develop signs of prolonged toxic polyneuritis, anaemia and haemorrhagic diathesis connected with the impaired thrombocytopoiesis. Typical of toxaphene is an allergic bronchopneumonia.

Acute intoxications with OCPs last up to 72 hours. When organ function has been seriously impaired, the illness may continue up to several weeks. Complications in cases of liver and kidney damage can be long-lasting.

Chronic poisoning

During the application of OCPs in agriculture as well as in their production, poisoning is most commonly chronic—that is, low doses of exposure over time. Acute intoxication (or high-level exposures at a particular instant) are less common and are usually the result of misuse or accidents, both in the home and in industry. Chronic intoxication is characterized by damage to the nervous, digestive and cardiovascular systems and the blood-formation process. All OCPs are CNS stimulants and are capable of producing convulsions, which frequently appear to be epileptic in character. Abnormal electroencephalographic (EEG) data have been recorded, such as irregular alpha rhythms and other abnormalities. In some cases bitemporal sharp-peaked waves with shifting localization, low voltage and diffuse theta activity have been observed. In other cases paroxysmal emissions have been registered, composed of slow sharp-peaked waves, sharp-peaked complexes and rhythmic peaks with low voltage.

Polyneuritis, encephalopolyneuritis and other nervous system effects have been described following occupational exposure to OCPs. Tremor of the limbs and alterations in the electromyograms (EMGs) have also been observed in workers. In workers handling OCPs such as BHC, polychloropinene, hexachlorobutadiene and dichloroethane, non-specific signs (e.g., diencephalic signs) have been observed and very often develop together with other signs of chronic intoxication. The most common signs of intoxication are headache, dizziness, numbness and tingling in the limbs, rapid changes in blood pressure and other signs of circulatory disturbances. Less frequently, colic pains below the right ribs and in the region of the umbilicus, and dyskinesia of the bile ducts, are observed. Behavioural changes, such as disturbances of sensory and equilibrium functions, are found. These symptoms are often reversible after cessation of the exposure.

OCPs cause liver and kidney damage. Microsomal enzyme induction has been observed, and increased ALF and aldolase activity have also been reported. Protein synthesis, lipoid synthesis, detoxification, excretion and liver functions are all affected. Reduction of creatinine clearance and phosphorus reabsorption are reported in workers exposed to pentachlorophenol, for example. Pentachlorophenol, along with the family of chlorophenols, are also considered possible human carcinogens (group 2B as classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)). Toxaphene is also considered to be a group 2B carcinogen.

Cardiovascular disturbances have been observed in exposed persons, most frequently demonstrated as dyspnoea, high heart rate, heaviness and pain in the heart region, increased heart volume and hollow heart tones.

Blood and capillary disturbances have also been reported following contact with OCPs. Thrombopenia, anaemia, pancytopenia, agranulocytosis, haemolysis and capillary disorders have all been reported. Medullar aplasia can be complete. The capillary damage (purpura) can develop following long- or short-term but intensive exposures. Eosinopenia, neutropenia with lymphocytosis, and hypochromic anaemia have been observed in workers subjected to prolonged exposures.

Skin irritation is reported to follow from skin contact with some OCPs, particularly chlorinated terpenes. Often chronic intoxications are clinically demonstrated by signs of allergic damage.

Organophosphate Pesticides

The organophosphorus pesticides are chemically related esters of phosphoric acid or certain of its derivatives. The organic phosphates are also identified by a common pharmacological property—the ability to inhibit the action of the cholinesterase enzymes.

Parathion is among the most dangerous of the organophosphates and is discussed in some detail here. In addition to parathion’s pharmacological effects, no insect is immune to its lethal action. Its physical and chemical properties have rendered it useful as an insecticide and acaricide for agricultural purposes. The description of parathion’s toxicity applies to other organophosphates, although their effects may be less rapid and extensive.

The toxic action of all organic phosphates is on the CNS through inhibition of the cholinesterase enzymes. Inhibiting these cholinesterases produces excessive and continuous stimulation of those muscle and gland structures which are activated by acetylcholine, to a point where life can no longer be sustained. Parathion is an indirect inhibitor because it must be converted in the environment or in vivo before it can effectively inhibit cholinesterase.

Organophosphates can generally enter the body by any route. Serious and even fatal poisoning may occur by ingesting a small amount of parathion while eating or smoking, for example. Organophosphates may be inhaled when dusts or volatile compounds are even briefly handled. Parathion is easily absorbed through the skin or the eye. The ability to penetrate the skin in fatal quantities without the warning of irritation makes parathion especially difficult to handle.

Signs and symptoms of organophosphate poisoning can be explained on the basis of cholinesterase inhibition. Early or mild poisoning may be hard to distinguish because of a number of other conditions; heat exhaustion, food poisoning, encephalitis, asthma and respiratory infections share some of the manifestations and confuse the diagnosis. Symptoms can be delayed for several hours after the last exposure but rarely longer than 12 hours. Symptoms most often appear in this order: headaches, fatigue, giddiness, nausea, sweating, blurred vision, tightness in the chest, abdominal cramps, vomiting and diarrhoea. In more advanced poisoning, difficult breathing, tremors, convulsions, collapse, coma, pulmonary oedema and respiratory failure follow. The more advanced the poisoning, the more obvious are the typical signs of cholinesterase inhibition, which are: pinpoint pupils; rapid, asthmatic type breathing; marked weakness; excessive sweating; excessive salivation; and pulmonary oedema.

In very severe parathion poisoning, in which the victim has been unconscious for some time, brain damage from anoxia may occur. Fatigue, ocular symptoms, electroencephalogram abnormalities, gastrointestinal complaints, excessive dreams and exposure intolerance to parathion have been reported to persist for days to months following acute poisoning. There is no evidence that permanent impairment occurs.

Chronic exposure to parathion may be cumulative in the sense that repeated exposures closely following each other can reduce cholinesterase faster than it can be regenerated, to the point where a very small exposure can precipitate acute poisoning. If the person is removed from exposure, clinical recovery is usually rapid and complete within a few days. The red blood cells and plasma should be tested for cholinesterase inhibition when phosphate ester poisoning is suspected. Red cell cholinesterase activity is most often reduced and close to zero in severe poisoning. Plasma cholinesterase is also severely reduced and is a more sensitive and more rapid indicator of exposure. There is no advantage in chemical determinations of parathion in the blood because metabolism of the pesticide is too rapid. However, p-nitrophenol, an end-product of the metabolism of parathion, can be determined in the urine. Chemical examination to identify the pesticide can be made on contaminated clothing or other material where contact is suspected.

Carbamates and Thiocarbamates

The biological activity of carbamates was discovered in 1923 when the structure of the alkaloid eserine (or physostigmine) contained in the seeds of Calabar beans was first described. In 1929 physostigmine analogues were synthesized, and soon such derivatives of dithiocarbamic acid as thiram and ziram were available. The study of carbamic compounds began in the same year, and now more than 1,000 carbamic acid derivatives are known. More than 50 of them are used as pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and nematocides. In 1947 the first carbamic acid derivatives having insecticide properties were synthesized. Some thiocarbamates have proved effective as vulcanization accelerators, and derivatives of dithiocarbamic acid have been obtained for the treatment of malignant tumours, hypoxia, neuropathies, radiation injuries and other diseases. Aryl esters of alkylcarbamic acid and alkyl esters of arylcarbamic acid are also used as pesticides.

Some carbamates can produce sensitization in exposed individuals, and a variety of foetotoxic, embryotoxic and mutagenic effects have also been observed for members of this family.

Chronic effects

The specific effects produced by acute poisoning have been described for each substance listed. A review of the specific effects gained from an analysis of published data makes it possible to distinguish similar features in the chronic action of the different carbamates. Some authors believe that the main toxic effect of carbamic acid esters is the involvement of the endocrine system. One of the peculiarities of carbamate poisoning is the possible allergic reaction of exposed subjects. The toxic effects of carbamates may not be immediate, which can present a potential hazard because of lack of warning. Results from animal experiments are indicative of embryotoxic, teratogenic, mutagenic and carcinogenic effects of some carbamates.

Baygon (isopropoxyphenyl-N-methylcarbamate) is produced by reaction of alkyl isocyanate with phenols, and is used as an insecticide. Baygon is a systemic poison. It causes inhibition of the serum cholinesterase activity up to 60% after oral administration of 0.75 to 1 mg/kg. This highly toxic substance exerts a weak effect on the skin.

Carbaryl is a systemic poison which produces moderately severe acute effects when ingested, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. It may cause local skin irritation. Being a cholinesterase inhibitor, it is much more active in insects than in mammals. Medical examinations of workers exposed to concentrations of 0.2 to 0.3 mg/m3 seldom reveal a fall in cholinesterase activity.

Betanal (3-(methoxycarbonyl)aminophenyl-N-(3-methylphenyl) carbamate; N-methylcarbanilate) belongs to the arylcarbamic acid alkyl esters and is used as a herbicide. Betanal is slightly toxic for the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. Its dermal toxicity and local irritation are insignificant.

Isoplan is a highly toxic member of the group, its action, like that of Sevin and others, being characterized by the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity. Isoplan is used as an insecticide. Pyrimor (5,6-dimethyl-2-dimethylamino-4-pyrimidinyl methylcarbamate) is a derivative of arylcarbamic acid alkyl esters. It is highly toxic for the gastrointestinal tract. Its general absorption and local irritative effect are not very pronounced.

Thiocarbamic Acid Esters

Ronite (sym-ethylcyclohexylethyl thiocarbamate; Eurex); Eptam (sym-ethyl-N,N-dipropyl thiocarbamate); and Tillam (sym-propyl-N-ethyl-N-butylthiocarbamate) are esters which are synthesized by reaction of alkylthiocarbamates with amines and of alkaline mercaptides with carbamoyl chlorides. They are effective herbicides of selective action.

The compounds of this group are slightly to moderately toxic, and the toxicity is reduced when they are absorbed through the skin. They can affect the oxidative processes as well as the nervous and endocrine systems.

Dithiocarbamates and bisdithiocarbamates include the following products, which have much in common as regards their use and their biological effects. Ziram is used as a vulcanization accelerator for synthetic rubbers and, in agriculture, as a fungicide and seed fumigant. This compound is very irritant to the conjunctiva and upper airway mucous membranes. It can cause extreme pain in the eyes, skin irritation and liver function disorders. It has embryotoxic and teratogenic effects. TTD is used as a seed fumigant, irritates the skin, causes dermatitis and affects the conjunctiva. It increases sensitivity to alcohol. Nabam is a plant fungicide and serves as an intermediate in the production of other pesticides. It is irritating to the skin and mucous membranes, and it is a narcotic in high concentrations. In the presence of alcohol it can cause violent vomiting. Ferbam is a fungicide of relatively low toxicity, but may cause renal function disorders. It irritates the conjunctiva, the mucous membranes of the nose and upper airways, and the skin.

Zineb is an insecticide and fungicide that can cause irritation of the eyes, nose and larynx, and is harmful if inhaled or swallowed. Maneb is a fungicide that can cause irritation of the eyes, nose and larynx, and is harmful if inhaled or swallowed. Vapam (sodium methyldithiocarbamate; carbation) is white crystalline powder of unpleasant smell similar to that of carbon disulphide. It is an effective soil fumigant which destroys weed seeds, fungi and insects. It irritates the skin and mucous membranes.

Rodenticides

Rodenticides are toxic chemicals used for the control of rats, mice and other pest species of rodents. An effective rodenticide must conform to stringent criteria, a fact that is borne out by the small number of compounds that are currently in satisfactory use.

Poisoned baits are the most generally effective and widely used means of formulating rodenticides, but some are used as “contact” poisons (i.e., dusts, foams and gels), where the toxicant adheres to the fur of the animal and is ingested during subsequent grooming, while a few are applied as fumigants to burrows or infested premises. Rodenticides may conveniently be divided into two categories, depending on their mode of action: acute (single dose) poisons and chronic (multiple dose) poisons.

Acute poisons, such as zinc phosphide, norbormide, fluoracetamide, alpha-chloralose, are highly toxic compounds, with LD50s that are usually less than 100 mg/kg, and can cause death after a single dose consumed during a period not longer than a few hours.

Most acute rodenticides have the disadvantages of producing symptoms of poisoning rather quickly, of being generally rather non-specific, and lacking satisfactory antidotes. They are used at relatively high concentrations (0.1 to 10%) in bait.

Chronic poisons, which may act, for example, as anticoagulants (e.g., calciferol), are compounds that, having a cumulative mode of action, may need to be eaten by the prey over a succession of days to cause death. Anticoagulants have the advantage of producing symptoms of poisoning very late, usually well after the target species has eaten a lethal dose. An effective antidote to anticoagulants is available for those accidentally exposed. Chronic poisons are used at relatively low concentrations (0.002 to 0.1%).

Application

Rodenticides intended for use in baits are available in one or more of the following forms: technical grade material, concentrate (“master-mix”) or ready-to-use bait. Acute poisons are usually acquired as the technical material and mixed with the bait-base shortly before use. Chronic poisons, because they are used at low concentrations, are normally sold as concentrates, where the active ingredient is incorporated into a finely powdered flour (or talc) base.

When the final bait is prepared, the concentrate is added to the bait-base at the relevant rate. If the bait-base is of a coarse consistency, it may be necessary to add a vegetable or mineral oil at a prescribed rate to act as a “sticker”, thus ensuring that the poison adheres to the bait-base. It is commonly compulsory for a warning dye to be added to concentrates or ready-to-use baits.

In control treatments against rats and mice, poisoned baits are laid at frequent intervals throughout the infested area. When acute rodenticides are used, better results are obtained when unpoisoned bait (“prebait”) is laid for a few days before the poison is given. In “acute” treatments, poisoned bait is presented for a few days only. When anticoagulants are used, prebaiting is unnecessary, but the poison should remain in position for 3 to 6 weeks to achieve complete control.

Contact formulations of rodenticides are especially useful in situations where baiting is difficult for any reason, or where the rodents are not being drawn satisfactorily off their normal diet. The poison is usually incorporated in a finely divided powder (e.g., talc), which is laid on runways or around bait points, or is blown into burrows, wall cavities and so on. The compound may also be formulated in gels or foams, which are inserted into burrows.

The use of contact rodenticides relies on the target animal ingesting the poison while grooming itself. Because the amount of dust (or foam, etc.) adhering to the fur may be small, the concentration of the active ingredient in the formulation is usually relatively high, making it safe to use only where the contamination of food and so on cannot occur. Other specialized formulations of rodenticides include water baits and wax-impregnated blocks. The former, which are aqueous solutions of soluble compounds, are especially useful in dry environments. The latter are made by impregnating the toxicant and bait-base in molten paraffin wax (of low melting point) and casting the mixture into blocks. Wax-impregnated baits are designed to withstand wet climates and insect attack.

Hazards of rodenticides

Although toxicity levels of rodenticides may vary between target and non-target species, all poisons must be presumed to be potentially lethal to humans. Acute poisons are potentially more dangerous than chronic ones because they are rapid in action, non-specific and generally lack effective antidotes. Anticoagulants, on the other hand, are slow and cumulative, allowing adequate time for the administration of a reliable antidote, such as vitamin K.

As stated above, the concentrations of active ingredients in contact formulations of a given poison are higher than those in bait preparations, thus making operator hazard considerably greater. Fumigants present a special danger when used to treat infested premises, holds of ships and so on, and should be used only by trained technicians. The gassing of rodent burrows, although less hazardous, must also be carried out with extreme caution.

Herbicides

Grassy and broad-leaved weeds compete with crop plants for light, space, water and nutrients. They are hosts to bacteria, fungi and viruses, and hamper mechanical harvesting operations. Losses in crop yields as a result of weed infestation can be very heavy, commonly reaching 20 to 40%. Weed-control measures such as hand weeding and hoeing are ineffective in intensive farming. Chemical weedkillers or herbicides have successfully replaced mechanical methods of weed control.

In addition to their use in agriculture in cereals, meadows, open fields, pastures, fruit growing, greenhouses and forestry, herbicides are applied on industrial sites, railway tracks and power lines to remove vegetation. They are used for destroying weeds in canals, drainage channels and natural or artificial pools.

Herbicides are sprayed or dusted on weeds or on the soil they infest. They remain on the leaves (contact herbicides) or penetrate into the plant and so disturb its physiology (systemic herbicides). They are classified as non-selective (total—used to kill all vegetation) and selective (used to suppress the growth of or kill weeds without damaging the crop). Both non-selective and selective can be contact or systemic.

Selectivity is true when the herbicide applied in the correct dose and, at the right time, is active against certain species of weed only. An example of true selective herbicides are the chlorophenoxy compounds, which affect broad-leaved but not grassy plants. Selectivity can also be achieved by placement (i.e., by using the herbicide in such a way that it comes into contact with the weeds only). For example, paraquat is applied to orchard crops, where it is easy to avoid the foliage. Three types of selectivity are distinguished:

1. physiological selectivity, which relies upon the plant’s ability to degrade the herbicide into non-phytotoxic components

2. physical selectivity, which exploits the particular habit of the cultivated plant (e.g., the upright in cereals) and/or a specially fashioned surface (e.g., wax-coating, resistant cuticule) protecting the plant against herbicide penetration

3. positional selectivity, in which the herbicide remains fixed in the upper soil layers adsorbed on colloidal soil particles and does not reach the root zone of the cultivated plant, or at least not in harmful quantities. Positional selectivity depends on the soil, precipitation and temperature as well as the water solubility and soil adsorption of the herbicide.

Some commonly used herbicides

Following are brief descriptions of acute and chronic effects associated with some commonly used herbicides.

Atrazine gives rise to decreased body weight, anaemia, disturbed protein and glucose metabolism in rats. It causes occupational contact dermatitis due to skin sensitization. It is considered a possible human carcinogen (IARC group 2B).

Barban, in repeated contact with 5% water emulsion, causes severe skin irritation in rabbits. It provokes skin sensitization in both experimental animals and agricultural workers, and causes anaemia, methaemoglobinaemia and changes in lipid and protein metabolism. Ataxia, tremor, cramps, bradycardia and ECG deviations are found in experimental animals.

Chlorpropharm can produce slight dermal irritation and penetration. In rats, exposure to atrazine causes anaemia, methaemoglobinaemia and reticulocytosis. Chronic application causes skin carcinoma in rats.

Cycloate causes polyneuropathia and liver damage in experimental animals. No clinical symptoms have been described after occupational exposure of workers for three consecutive days.

2,4-D poses moderate dermal toxicity and skin irritancy risks to exposed persons. It is highly irritating to the eyes. Acute exposures in workers provoke headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, raised temperature, low blood pressure, leucocytosis, and heart and liver injury. Chronic occupational exposure without protection may cause nausea, liver functional changes, contact toxic dermatitis, irritation of airways and eyes, as well as neurological changes. Some of the derivatives of 2,4-D are embryotoxic and teratogenic for experimental animals in high doses only.

2,4-D and the related phenoxy herbicide 2,4,5-T are rated as group 2B carcinogens (possible human carcinogens) by the IARC. Lymphatic cancers, particularly non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), have been associated in Swedish agricultural workers with exposure to a commercial mixture of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T (similar to the herbicide Agent Orange used by the US military in Viet Nam during the years 1965 to 1971). Possible carcinogenicity is often ascribed to contamination of 2,4,5-T with 2,3,7,8-tetrachloro-dibenzo-p-dioxin. However, a US National Cancer Institute research group reported a risk of 2.6 for adult NHL among Kansas residents exposed to 2,4-D alone, which is not thought to be dioxin-contaminated.

Dalapon-Na can cause depression, an unbalanced gait, decreased body weight, kidney and liver changes, thyroid and pituitary dysfunctions, and contact dermatitis in workers who are exposed. Diallate has dermal toxicity and causes irritation to the skin, eyes and mucous membranes. Diquat is an irritant to the skin, eyes and upper respiratory tract. It can cause a delay in the healing of cuts and wounds, gastrointestinal and respiratory disturbances, bilateral cataract and functional liver and kidney changes.

Dinoseb presents dangers because of its toxicity through dermal contact. It can cause moderate skin and pronounced eye irritation. The fatal dose for humans is about 1 to 3 g. After an acute exposure, Dinoseb causes central nervous system disturbances, vomiting, reddening (erythema) of the skin, sweating and high temperature. Chronic exposure without protection results in decreased weight, contact (toxic or allergic) dermatitis and gastrointestinal, liver and kidney disturbances. Dinoseb is not used in many countries because of its serious adverse effects.

Fluometuron is a moderate skin sensitizer in guinea-pigs and humans. It has been observed to cause decreased body weight, anaemia, and liver, spleen and thyroid gland disturbances. The biological action of diuron is similar.

Linuron causes mild irritation to the skin and eyes, and has low cumulative toxicity (threshold value after single inhalation 29 mg/m3). It causes CNS, liver, lung and kidney changes in experimental animals, as well as thyroid dysfunction.

MCPA is highly irritant to skin and mucous membranes, has low cumulative toxicity and is embryotoxic and teratogenic in high doses in rabbits and rats. Acute poisoning in humans (an estimated dose of 300 mg/kg) results in vomiting, diarrhoea, cyanosis, mucus burns, clonic spasms, and myocardium and liver injury. It provokes severe contact toxic dermatitis in workers. Chronic exposure without protection results in dizziness, nausea, vomiting, stomach aches, hypotonia, enlarged liver, myocardium dysfunction and contact dermatitis.

Molinate can reach a toxic concentration after single inhalation of 200 mg/m3 in rats. It causes liver, kidney and thyroid disturbances, and is gonadotoxic and teratogenic in rats. It is a moderate skin sensitizer in humans.

Monuron in high doses can result in liver, myocardium and kidney disturbances. It causes skin irritation and sensitization. Similar effects are shown by monolinuron, chloroxuron, chlortoluron and dodine.

Nitrofen is a strong skin and eye irritant. Chronic occupational exposure without protection results in CNS disturbances, anaemia, raised temperature, decreased body weight, fatigue and contact dermatitis. It is considered a possible human carcinogen (group 2B) by the IARC.

Paraquat has dermal toxicity and irritant effects on skin or mucous membranes. It causes nail damage and nose bleeding in occupational conditions without protection. Accidental oral poisoning with paraquat has resulted when it was left within reach of children or transferred from the original container into a bottle used for a beverage. Early manifestations of such intoxication are corrosive gastrointestinal effects, renal tubular damage and liver dysfunction. Death is due to circulatory collapse and progressive pulmonary damage (pulmonary oedema and haemorrhage, intra-alveolar and interstitial fibrosis with alveolitis and hyaline membranes), clinically revealed by dyspnoea, hypoxaemia, basal rales and roentgenographic evidence of infiltration and athelectasis. The renal failure is followed by lung damage, and accompanied in some cases by liver or myocardium disturbances. Mortality is higher with poisoning from liquid concentrate formulations (87.8%), and lower from granular forms (18.5%). The fatal dose is 6 g paraquat ion (equivalent to 30 ml Gramoxone or 4 packets of Weedol), and no survivors are reported at greater doses, irrespective of the time or vigour of treatment. Most survivors had ingested less than 1 g paraquat ion.

Potassium cyanate is associated with high inhalation and dermal toxicity in experimental animals and humans due to the metabolic conversion to cyanide, which is discussed elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.