Adapted from 3rd edition, “Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety”.

Brewing is one of the oldest industries: beer in different varieties was drunk in the ancient world, and the Romans introduced it to all their colonies. Today it is brewed and consumed in almost every country, particularly in Europe and areas of European settlement.

Process Overview

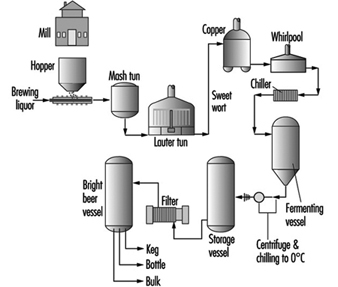

The grain used as the raw material is usually barley, but rye, maize, rice and oatmeal are also employed. In the first stage the grain is malted, either by causing it to germinate or by artificial means. This converts the carbohydrates to dextrin and maltose, and these sugars are then extracted from the grain by soaking in a mash tun (vat or cask) and then agitating in a lauter tun. The resulting liquor, known as sweet wort, is then boiled in a copper vessel with hops, which give a bitter flavour and helps to preserve the beer. The hops are then separated from the wort and it is passed through chillers into fermenting vessels where the yeast is added—a process known as pitching—and the main process of converting sugar into alcohol is carried out. (For discussion of fermentation see the chapter Pharmaceutical industry.) The beer is then chilled to 0 °C, centrifuged and filtered to clarify it; it is then ready for dispatch by keg, bottle, aluminium can or bulk transport. Figure 1 is a flow chart of the brewing process.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the brewing process.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Manual handling

Manual handling accounts for most of the injuries in breweries: hands are bruised, cut or punctured by jagged hoops, splinters of wood and broken glass. Feet are bruised and crushed by falling or rolling barrels. Much can be done to prevent these injuries by suitable hand and foot protection. Increase in automation and standardization of barrel size (say at 50 l) can reduce the lifting risks. The back pain caused by lifting and carrying of barrels and so on can be dramatically reduced by training in sound lifting techniques. Mechanical handling on pallets can also reduce ergonomic problems. Falls on wet and slippery floors are common. Non-slip surfaces and footwear, and a regular system of cleaning, are the best precaution.

Handling of grain can produce barley itch, caused by a mite infesting the grain. Mill-worker’s asthma, sometimes called malt fever, has been recorded in grain handlers and has been shown to be an allergic response to the grain weevil (Sitophilus granarius). Manual handling of hops can produce a dermatitis due to the absorption of the resinous essences through broken or chapped skin. Preventive measures include good washing and sanitary facilities, efficient ventilation of the workrooms, and medical supervision of the workers.

When barley is malted by the traditional method of steeping it and then spreading it on floors to produce germination, it may become contaminated by Aspergillus clavatus, which can produce growth and spore formation. When the barley is turned to prevent root matting of the shoots, or when it is loaded into kilns, the spores may be inhaled by the workers. This may produce extrinsic allergic alveolitis, which in symptomatology is indistinguishable from farmer’s lung; exposure in a sensitized subject is followed by a rise in body temperature and shortness of breath. There is also a fall in normal lung functions and a decrease in the carbon monoxide transfer factor.

A study of organic dusts containing high levels of endotoxin in two breweries in Portugal found the prevalence of symptoms of organic dust toxic syndrome, which is distinct from alveolitis or hypersensitivity pneumonia, to be 18% among brewery workers. Mucous membrane irritation was found among 39% of workers (Carveilheiro et al. 1994).

In an exposed population, the incidence of the disease is about 5%, and continued exposure produces severe respiratory incapacity. With the introduction of automated malting, where workers are not exposed, this disease has largely been eliminated.

Machinery

Where malt is stored in silos, the opening should be protected and strict rules enforced regarding entry of personnel, as described in the box on confined spaces in this chapter. Conveyors are much used in bottling plants; traps in the gearing between belts and drums can be avoided by efficient machinery guarding. There should be an effective lockout/tagout programme for maintenance and repair. Where there are walkways across or above conveyors, frequent stop buttons should also be provided. In the filling process, very serious lesions can be caused by bursting bottles; adequate guards on the machinery and face guards, rubber gloves, rubberized aprons and non-slip boots for the workers can prevent injury.

Electricity

Owing to the prevailing damp conditions, electrical installations and equipment need special protection, and this applies particularly to portable apparatus. Ground fault circuit interrupters should be installed where necessary. Wherever possible, low voltages should be used, especially for portable inspection lamps. Steam is used extensively, and burns and scalds occur; lagging and protection of pipes should be provided, and safety locks on steam valves will prevent accidental release of scalding steam.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is formed during fermentation and is present in fermenting tuns, as well as vats and vessels that have contained beer. Concentrations of 10%, even if breathed only for a short time, produce unconsciousness, asphyxia and eventual death. Carbon dioxide is heavier than air, and efficient ventilation with extraction at a low height is essential in all fermentation chambers where open vats are used. As the gas is imperceptible to the senses, there should be an acoustic warning system which will operate immediately if the ventilation system breaks down. Cleaning of confined spaces presents serious hazards: the gas should be dispelled by mobile ventilators before workers are permitted to enter, safety belts and lifelines and respiratory protective equipment of the self-contained or supplied-air type should be available, and another worker should be posted outside for supervision and rescue, if necessary.

Gassing

Gassing has occurred during relining of vats with protective coatings containing toxic substances such as trichloroethylene. Precautions should be taken similar to those listed above against carbon dioxide.

Refrigerant gases

Chilling is used to cool the hot wort before fermentation and for storage purposes. Accidental discharge of refrigerants can produce serious toxic and irritant effects. In the past, chloromethane, bromomethane, sulphur dioxide and ammonia were mainly used, but today ammonia is most common. Adequate ventilation and careful maintenance will prevent most risks, but leak detectors and self-contained breathing apparatus should be provided for emergencies frequently tested. Precautions against explosive risks may also be necessary (e.g., flameproof electrical fittings, elimination of naked flames).

Hot work

In some processes, such as cleaning out mash tuns, workers are exposed to hot, humid conditions while performing heavy work; cases of heat stroke and heat cramps can occur, especially in those new to the work. These conditions can be prevented by increased salt intake, adequate rest periods and the provision and use of shower baths. Medical supervision is necessary to prevent mycoses of the feet (e.g., athlete’s foot), which spread rapidly in hot, humid conditions.

Throughout the industry, temperature and ventilation control, with special attention to the elimination of steam vapour, and the provision of PPE are important precautions, not only against accident and injury but also against more general hazards of damp, heat and cold (e.g., warm working clothes for workers in cold rooms).

Control should be exercised to prevent excessive consumption of the product by the persons employed, and alternative hot beverages should be available at meal breaks.

Noise

When metal barrels replaced wooden casks, breweries were faced with a severe noise problem. Wooden casks made little or no noise during loading, handling or rolling, but metal casks when empty create high noise levels. Modern automated bottling plants generate a considerable volume of noise. Noise can be reduced by the introduction of mechanical handling on pallets. In the bottling plants, the substitution of nylon or neoprene for metal rollers and guides can substantially reduce the noise level.