Bakeries

Adapted from 3rd edition, “Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety”.

The manufacture of foodstuffs from starches and sugars is done in bakeries and biscuit-, pastry- and cake-making establishments. The safety and health hazards presented by the raw materials, the plant and equipment and the manufacturing processes in these plants are similar. This article deals with small-scale bakeries and covers bread and various related products.

Production

There are three main stages in breadmaking—mixing and moulding, fermentation and baking. These processes are carried out in different work areas—the raw materials store, the mixing and moulding room, cold and fermentation chambers, the oven, the cooling room and the wrapping and packaging shop. The sales premises are frequently attached to the manufacturing shops.

Flour, water, salt and yeast are mixed together to make dough; hand mixing has been largely replaced by the use of mechanical mixing machines. Beating machines are used in the manufacture of other products. The dough is left to ferment in a warm, humid atmosphere, after which it is divided, weighed, moulded and baked (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Bread production for a supermarket chain in Switzerland

Small-scale production ovens are of the fixed-hearth type with direct or indirect heat transfer. In the direct type, the refractory lining is heated either intermittently or continuously before each charge. Off-gases pass to the chimney through the adjustable orifices at the rear of the chamber. In the indirect type, the chamber is heated by steam passing through tubes in the chamber wall or by forced hot-air circulation. The oven may be fired by wood, coal, oil, town gas, liquefied petroleum gas or electricity. In rural areas, ovens with hearths heated directly by wood fires are still found. Bread is charged into the oven on paddles or trays. The oven interior can be illuminated so that the baking bread can be observed through the chamber windows. During baking, the air in the chamber becomes charged with water vapour given off by the product and/or introduced in the form of steam. The excess usually escapes up the chimney, but the oven door may also be left open.

Small-scale production ovens are of the fixed-hearth type with direct or indirect heat transfer. In the direct type, the refractory lining is heated either intermittently or continuously before each charge. Off-gases pass to the chimney through the adjustable orifices at the rear of the chamber. In the indirect type, the chamber is heated by steam passing through tubes in the chamber wall or by forced hot-air circulation. The oven may be fired by wood, coal, oil, town gas, liquefied petroleum gas or electricity. In rural areas, ovens with hearths heated directly by wood fires are still found. Bread is charged into the oven on paddles or trays. The oven interior can be illuminated so that the baking bread can be observed through the chamber windows. During baking, the air in the chamber becomes charged with water vapour given off by the product and/or introduced in the form of steam. The excess usually escapes up the chimney, but the oven door may also be left open.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Working conditions

The working conditions in artisanal bakehouses can have the following features: night work starting at 2:00 or 3:00 a.m., especially in Mediterranean countries, where the dough is prepared in the evening; premises often infested with parasites such as cockroaches, mice and rats, which may be carriers of pathogenic micro-organisms (suitable construction materials should be used to ensure that these premises are maintained in an adequate state of hygiene); house-to-house bread delivery, which is not always carried out in adequate conditions of hygiene and which may entail an excess workload; low wages supplemented by board and lodging.

Premises

Premises are often old and dilapidated and lead to considerable safety and health problems. The problem is particularly acute in rented premises for which neither the lessor nor the lessee can afford the cost of renovation. Floor surfaces can be very slippery when wet, although reasonably safe when dry; non-slip surfaces should be provided whenever possible. General hygiene suffers owing to defective sanitary facilities, increased hazards of poisoning, explosions and fire, and the difficulty of modernizing heavy bakehouse plant owing to the terms of the lease. Small premises cannot be suitably divided up; consequently traffic aisles are blocked or littered, equipment is inadequately spaced, handling is difficult, and the danger of slips and falls, collisions with plant, burns and injuries resulting from overexertion is increased. Where premises are located on two or more storeys there is the danger of falls from a height. Basement premises often lack emergency exits, have access stairways which are narrow, winding or steep and are fitted with poor artificial lighting. They are usually inadequately ventilated, and consequently temperatures and humidity levels are excessive; the use of simple cellar ventilators at street level merely leads to the contamination of the bakehouse air by street dust and vehicle exhaust gases.

Accidents

Knives and needles are widely used in artisanal bakeries, with a risk of cuts and puncture wounds and subsequent infection; heavy, blunt objects such as weights and trays may cause crush injuries if dropped on the worker’s foot.

Ovens present a number of hazards. Depending on the fuel used, there is the danger of fire and explosion. Flashbacks, steam, cinders, baked goods or uninsulated plant may cause burns or scalds. Firing equipment which is badly adjusted or has insufficient draw, or defective chimneys, may lead to the accumulation of unburnt fuel vapours or gases, or of combustion products, including carbon monoxide, which may cause intoxication or asphyxia. Defective electrical equipment and installations, especially of the portable or mobile type, may cause electric shock. The sawing or chopping of wood for wood-fired ovens may result in cuts and abrasions.

Flour is delivered in sacks weighing up to 100 kg, and these must often be lifted and carried by workers through tortuous gangways (steep inclines and staircases) to the storage rooms. There is the danger of falls while carrying heavy loads, and this arduous manual handling may cause back pain and lesions of intervertebral discs. The hazards may be avoided by: providing suitable access ways to the premises; stipulating a suitable maximum weight for sacks of flour; using mechanical handling equipment of a type suitable for use in small undertakings and at a price within the range of most artisanal workers; and by wider use of bulk flour transport, which is, however, suitable only when the baker has a sufficiently large turnover.

Flour dust is also a fire and explosion hazard, and proper precautions should be taken, including fire and explosion suppression systems.

In mechanized bakeries, dough which is in an active state of fermentation may give off dangerous amounts of carbon dioxide; thorough ventilation should therefore be provided in confined spaces wherever the gas is likely to accumulate (dough chutes and so on). Workers should be trained in confined-space procedures.

A wide variety of machines are used in bread manufacture, particularly in industrial bakeries. Mechanization can bring serious accidents in its wake. Modern bakery machines are usually equipped with built-in guards whose correct operation often depends upon the functioning of electrical limit switches and positive interlocks. Feed hoppers and chutes present special hazards which can be eliminated by extending the length of the feed opening beyond arm’s length to prevent the operator from reaching the moving parts; hinged double gates or rotary flaps are sometimes used as feeding devices for the same purpose. Nips on dough brakes can be protected by either fixed or automatic guards. A variety of guards (covers, grids and so on) can be used on dough mixers to prevent access to the trapping zone while permitting insertion of additional material and scraping of the bowl. Increasing use is made of bread-slicing and wrapping machines with alternating saw blades or rotary knives; all moving parts should be completely enclosed, interlocking covers being provided where access is necessary. There should be a lockout/tagout programme for maintenance and repair of machinery.

Health Hazards

Bakehouse workers are usually lightly clothed and sweat profusely; they are subject to draughts and pronounced variations in ambient temperature when changing, for example, from oven charging to cooler work. Airborne flour dust may cause rhinitis, throat disorders, bronchial asthma (“baker’s asthma”) and eye diseases; sugar dust may cause dental caries. Airborne vegetable dust should be controlled by suitable ventilation. Allergic dermatitis may occur in persons with special predisposition. The above health hazards and the high incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis amongst bakers emphasize the need for medical supervision with frequent periodic examinations; in addition, strict personal hygiene is essential in the interests of both workers and the public in general.

Grain, Grain Milling and Grain-based Consumer Products

Grain goes through many steps and processes to be prepared for human consumption. The major steps are: collection, consolidation and storage at grain elevators; milling into an intermediate product such as starch or flour; and processing into finished products such as bread, cereal or snacks.

Grain Collection, Consolidation and Storage

Grains are grown on farms and moved to grain elevators. They are transported by truck, rail, barge or ship depending on the location of the farm and the size and type of elevator. Grain elevators are used to collect, classify and store agricultural products. Grains are separated according to their quality, protein content, moisture content and so on. Grain elevators consist of bins, tanks or silos with vertical and horizontal continuous belts. Vertical belts have cups on them to carry the grain up to weighing scales and horizontal belts for distribution of the grain into bins. Bins have discharges on the bottoms which deposit grain on a horizontal belt which conveys the product to a vertical belt for weighing and transportation or return to storage. Elevators can have capacities ranging from just a few thousand bushels at a country elevator to millions of bushels at a terminal elevator. As these products move towards processing, they may be handled many times through elevators of increasing size and capacity. When they are ready to be transported to another elevator or processing facility, they will be loaded into either truck, railcar, barge or ship.

Grain Milling

Milling is a series of operations involving the grinding of grains to produce starch or flour, most commonly from wheat, oats, corn, rye, barley or rice. The raw product is ground and sifted until the desired size is reached. Typically, milling involves the following steps: raw grain is delivered to a mill elevator; grain is cleaned and prepared for milling; grain is milled and separated by size and grain part; flour, starch and by-products are packaged for consumer distribution or bulk transported to be used in various industrial applications.

Grain-based Consumer Products Manufacturing

Bread, cereal and other baked goods are produced using a series of steps, including: combining raw ingredients, batter production and processing, product forming, baking or toasting, enrobing or frosting, packaging, casing, palletizing and final shipment.

Raw materials are often stored in bins and tanks. Some are handled in large bags or other containers. The materials are transported to processing areas using pneumatic conveyors, pumps or manual material-handling methods.

Dough production is a step where raw ingredients, including flour, sugar and fats or oils, and minor ingredients, such as flavorings, spices and vitamins, are combined in a cooking vessel. Any particulate ingredients are added along with puréed or pulped fruits. Nuts are usually husked and cut to size. Cookers (either continuous process or batch) are used. Processing of the dough into intermediate product stages can involve extruders, formers, pelletizers and shaping systems. Further processing can involve rolling systems, formers, heaters, dryers and fermentation systems.

Packaging systems take the finished product and encase it in a paper or plastic individual wrapping, place individual products in a box and then pack boxes on a pallet to prepare for shipment. Manual pallet stacking or product handling is used along with fork-lift trucks.

Mechanical Safety Issues

Equipment safety hazards include points of operation which can abrade, cut, bruise, crush, fracture and amputate. Workers can be protected by guarding or isolating the hazards, de-energizing all power sources prior to performing any maintenance or adjustment on the equipment and training workers in proper procedures to follow when working on the equipment.

The machines used to mill and convey products can be particularly dangerous. The pneumatic system and its rotary valves can cause severe finger or hand amputations. The equipment must be locked out while maintenance or clean-up is being performed. All equipment must be properly guarded and all workers need to be trained in proper operating procedures.

Processing systems have mechanical parts moving under automatic control which can cause severe injury, especially to fingers and hands. Cookers are hot and noisy, usually involving steam heating under pressure. Extrusion dies can have hazardous moving parts, including knives moving at high speed. Blenders and mixing machines can cause severe injuries and are particularly dangerous during clean-up between batches. Lockout and tagout procedures will minimize risk to workers. Slitter knives and water knives can cause severe lacerations and are especially dangerous during change-outs and adjustment procedures. Further processing can involve rolling systems, formers, heaters, dryers and fermentation systems, which present additional hazards to the extremities in the form of crushing and burn injuries. Manual handling and opening of bags can result in cuts and bruises.

Packaging systems have automated moving parts and can cause crushing or tearing injuries. Maintenance and adjustment procedures are particularly hazardous. Manual pallet stacking or product handling can cause repetitive strain injuries. Fork-lift trucks and hand pallet movers are also dangerous, and poorly stacked or secured loads can fall on nearby personnel.

Fire and Explosion

Fire and explosion can destroy grain-handling facilities and injure or kill workers and others who are in the facility or nearby at the time of explosion. Explosions require oxygen (air), fuel (grain dust), an ignition source of sufficient energy and duration (spark, flame or hot surface) and confinement (to allow pressure build-up). Typically, when an explosion occurs at a grain handling facility, it is not a single explosion but a series of explosions. The primary explosion, which can be quite small and localized, can suspend dust in the air throughout the facility in concentrations sufficient to sustain secondary explosions of great magnitude. The lower explosion limit for grain dust is approximately 20,000 mg/m3. Prevention of fire and explosion hazards can be accomplished by designing plants with minimal confinement (except for bins, tanks and silos); controlling dust emissions into air and accumulations on floors and equipment surfaces (enclosing product streams, LEV, housekeeping and grain additives such as food-grade mineral oil or water); and controlling the explosion (fire and explosion suppression systems, explosion venting). There should be adequate fire exits or means of escape. Firefighting equipment should be strategically located, and workers should be trained in emergency response; but only very small fires should be fought because of the explosion potential.

Health Hazards

Dust can be created when grain is moved or disturbed. Although most grain dusts are simple respiratory irritants, the dusts from unprocessed grain can contain moulds and other contaminants which can cause fever and allergic asthma reactions in sensitive persons. Employees tend not to work for prolonged times in dusty areas. Typically, a respirator is worn when needed. The highest dust exposures occur during loading/unloading operations or during major cleaning. Some research has indicated pulmonary function changes related to dust exposure. The current American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) TLVs for occupational exposure to grain dust are 4 mg/m3 for oat, wheat and barley and 10 mg/m3 for other grain dust (particulates, not otherwise classified).

Respiratory protection is often worn to minimize dust exposure. Approved dust respirators can be very effective if worn properly. Workers need to be trained in their proper use, maintenance and limitations. Housekeeping is essential.

Pesticides are used in the grain and grain-processing industries to control insects, rodents, birds, mould and so on. Some of the more common pesticides are phosphine, organophosphates and pyrethrins. Potential health effects can include dermatitis, dizziness, nausea and long-term problems with liver, kidney and nervous system functions. These effects occur only if employees are overexposed. Proper use of PPE and following safety procedures will prevent overexposure.

Most grain-processing facilities apply pesticides during shut-down times, when there are few employees in the buildings. Those workers present should be on the pesticide application team and receive special training. Re-entry rules should be followed to prevent overexposure. Many locations heat the entire structure to about 60 ºC for 24 to 48 hours in lieu of using chemical pesticides. Workers may also be exposed to pesticides on treated grain being brought to the truck cargo facility in trucks or rail cars.

Noise is a common problem in most grain-processing plants. The predominant noise levels range from 83 to 95 dBA, but can exceed 100 dBA in some areas. Relatively little acoustical absorption can be used due to the need for cleaning of equipment used in these facilities. Most floors and walls are made of cement, tile and stainless steel to allow easy cleaning and to prevent the facility from becoming a refuge for insects. Many employees move from area to area and spend little time working in the noisiest areas. This reduces personal exposure considerably, but hearing protection should be worn to reduce noise exposure to acceptable levels.

Working in a confined space such as a bin, tank or silo can present workers with health and physical hazards. The greatest concern is oxygen deficiency. Tightly sealed bins, tanks and silos can become oxygen deficient due to inert gases (nitrogen and carbon dioxide to prevent pest infestation) and biological action (insect infestation or mouldy grain). Prior to any entry into a bin, tank, silo or other confined space, the atmospheric conditions inside the confined space need to be checked for sufficient oxygen. If oxygen is less than 19.5%, the confined space must be ventilated. Confined spaces should also be checked for recent pesticide application or any other toxic material which may be present. Physical hazards in confined spaces include engulfment in the grain and entrapment in the space due to its configuration (inward sloping walls or entrapment in equipment inside the space). No worker should be in a confined space such as a grain silo, bin or tank while grain is being removed. Injury and death can be prevented by de-energizing and locking out all equipment associated with the confined space, ensuring that workers wear harnesses with lifelines while inside the confined space and maintaining a supply of breathable air. Prior to entry, the atmosphere inside a bin, silo or tank should be tested for the presence of combustible gases, vapours or toxic agents, and for the presence of sufficient oxygen. Employees must not enter bins, silos or tanks underneath a bridging condition, or where build-up of grain products on the sides could fall and bury them.

Medical Screening

Potential employees should be given a medical examination focusing on any pre-existing allergies and checking liver, kidney and lung function. Special examinations may be required for pesticide applicators and workers who use respiratory protection. Evaluations of hearing need to be made to assess any hearing loss. Periodic follow-up should seek to detect any changes.

Cocoa Production and the Chocolate Industry

Cocoa is indigenous to the Amazon region of South America, and, during the first years of the twentieth century, the southern region of Bahia provided the perfect conditions for its growth. The cocoa-producing region of Bahia is composed of 92 municipalities and Ilheus and Itabuna are its main centres. This region accounts for 87% of the national production of cocoa in Brazil, currently world’s the second largest producer of cocoa beans. Cocoa is also produced in about 50 other countries, with Nigeria and Ghana being major producers.

The vast majority of this production is exported to countries like Japan, the Russian Federation, Switzerland and the United States; half of this is sold as processed products (chocolate, vegetable fat, chocolate liquor, cocoa powder and butter) and the rest is exported as cocoa beans.

Process Overview

The industrial method for processing cocoa involves several stages. It begins with the storage of the raw material in adequate sheds, where it undergoes fumigation to prevent the proliferation of rodents and insects. Next, the process of cleaning the grains begins in order to remove any foreign objects or residues. Then all cocoa beans are dried out to extract excess moisture until an ideal level is reached. The next stage is the cracking of the grains in order to separate the skin from the core, followed by the roasting stage, which consists of the heating of the inner part of the grain.

The resulting product, which is in the shape of small particles known as “nibs”, is subject to a process of grinding (crushing), thus becoming a liquid paste, which in turn is strained and solidified in refrigeration chambers and sold as paste.

Most grinding companies normally separate the liquor through a process of pressing it until the fat is extracted and converted into two final products: cocoa butter and cocoa cake. The cake is packed in solid pieces while the cocoa butter is filtered, deodorized, cooled in refrigeration chambers and later packaged.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Although, the processing of cocoa is usually automated in such a way that it requires little manual contact and a high level of hygiene is maintained, the great majority of the employees in the industry still are exposed to a variety of occupational risks.

Noise and excessive vibration are problems found throughout the production line since, in order to prevent the easy access of rodents and insects, closed sheds are built with the machinery suspended on metal platforms. These machines must be subjected to proper maintenance and adjustment routines. Anti-vibratory devices should be installed. Noisy machinery should be isolated or noise reduction barriers should be used.

During the fumigation process, tablets of aluminium phosphate are utilized; as these come in contact with humid air, phosphine gas is released. It is recommended that grains remain covered for periods of 48 to 72 hours during and after these fumigation sessions. Air sampling should be done before re-entry.

The operation of grinders, hydraulic presses and drying machinery generate a great deal of heat with the high levels of noise; the high heat is intensified by the type of construction of the buildings. However, many safety measures can be adopted: use of barriers, isolation of the operations, implementation of schedules of working hours and breaks, availability of liquids to drink, use of adequate attire and the appropriate acclimatization of the employees.

In the areas of finished products, where the average temperature is 10 °C, staff members should wear appropriate clothing and have working periods of 20 to 40 minutes. The process of acclimatization is also important. Rest breaks in warm areas are necessary.

In the operations of product reception, where storage of raw materials and all finished products are packaged, ergonomically inadequate procedures and equipment are common. Mechanized equipment should replace manual handling where possible since moving and carrying loads can cause injuries, heavy articles can hit employees and injuries can result from the use of machinery without proper guards.

Procedures and equipment should be evaluated from an ergonomic point of view. Falls due to slippery floors are also a concern. In addition, there are other activities, like the cracking of the grains and the grinding and production of cocoa powder, where there are high levels of organic dust. Adequate dilution ventilation or local exhaust systems should be installed; processes and operations isolated and segregated as appropriate.

A rigorous programme of environmental risks prevention is highly recommended, in addition to the regular system of fire prevention and safety, adequate guarding of machinery and good standards of hygiene. Signs and informational bulletins should be posted in highly visible places and equipment and devices for the personal protection should be distributed to each worker. In maintaining machinery, a lockout/tagout programme should be instituted to prevent injuries.

Dairy Products Industry

Dairy products have formed an important element in human food since the earliest days when animals were first domesticated. Originally the work was done within the home or farm, and even now much is produced in small-scale enterprises, although in many countries large-scale industries are common. Cooperatives have been of great importance in the development of the industry and the improvement of its products.

In many countries, there are strict regulations governing the preparation of dairy products—for example, a requirement that all liquids be pasteurized. In most dairies, milk is pasteurized; sometimes it is sterilized or homogenized. Safe, high-quality dairy products are the goal of manufacturing plants today. While recent advances in technology allow for more sophistication and automation, safety is still a concern.

Liquid or fluid milk is the basic raw material for the dairy products industry. The milk is received via tanker trucks (or sometimes in cans) and is unloaded. Each tanker is checked for drug residues and temperature. The milk is filtered and stored in tanks/silos. Temperature of the milk should be less than 7 °C and held for no more than 72 hours. After storage, the milk is separated, the raw cream is stored in house or shipped elsewhere and the remaining milk is pasteurized. The raw cream temperature should also be less than 7 °C and held for no more than 72 hours. Before or after pasteurization (heating to 72°C for 15 seconds), vitamins may be added. If vitamins are added, proper concentrations must be administered. After pasteurization, the milk goes into a storage tank. The milk is then packaged, refrigerated and entered into distribution.

In the production of cheddar cheese, the incoming raw milk is filtered, stored, and the cream separated as discussed above. Before pasteurization, the dry and non-dairy ingredients are blended with the milk. This blended product is then pasteurized at a temperature greater than 72 °C for over 15 seconds. After pasteurization, the starter media (which has also been pasteurized) is added. The cheese-milk mixture then enters the cheese vat. At this time colour, salt (NaCl), rennet and calcium chloride (CaCl2) may be added. The cheese then enters the drain table. Salt may also be added at this time. Whey is then expelled and put into a storage tank. A metal detector can be used prior to filling to detect any metal fragments present in the cheese. After filling, the cheese is pressed, packaged, stored and entered into the distribution chain.

For the formation of butter, the raw cream from milk separation is either stored in house or received via trucks or cans. The raw cream is pasteurized at temperatures over 85 °C for over 25 seconds and placed in storage tanks. The cream is pre-heated and pumped into the churn. During churning, water, colour, salt and/or starter distillate may be added. After churning, the buttermilk that is produced is stored in tanks. The butter is pumped into a silo and subsequently packaged. A metal detector may be used prior to or after packaging to detect any metal fragments present in the butter. After packaging, the butter is palletized, stored and entered into the distribution chain.

In the production of dry milk, the raw milk is received, filtered and stored as previously discussed. After storage, the milk is preheated and separated. The raw cream is stored in house or shipped elsewhere. The remaining milk is pasteurized. The temperature of the raw cream and raw skim should be less than 7 °C and held for no more than 72 hours. The raw skim milk is pasteurized at a temperature over 72 °C for 15 seconds, evaporated by drying between heated cylinders or by spray drying and stored in tanks. After storage, the product enters a drying system. After drying, the product is cooled. Both the heated and cool air used must be filtered. After cooling, the product enters a bulk storage tank, is sifted and packaged. A magnet may be used prior to packaging to detect any ferrous metal fragments greater than 0.5 mm in the dry milk. A metal detector may be used prior to or after packaging. After packaging, the dry milk is stored and shipped.

Good Manufacturing Practices

Good manufacturing practices (GMPs) are guidelines to assist in the day-to-day operation of a dairy plant and to ensure the manufacture of a safe dairy product. Areas covered include premises, receiving/storage, equipment performance and maintenance, personnel training programmes, sanitation and recall programmes.

Microbiological, physical and chemical contamination of dairy products is a major industry concern. Microbiological hazards include Brucella, Clostridium botulinum, Listeria monocytogenes, hepatitis A and E, salmonella, Escherichia coli 0157:H7, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus and parasites. Physical hazards include metal, glass, insects, dirt, wood, plastic and personal effects. Chemical hazards include natural toxins, metals, drug residues, food additives and inadvertent chemicals. As a result, dairies do extensive drug, microbiological and other testing to ensure product purity. Steam and chemical cleaning of equipment is necessary to maintain sanitary conditions.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Safety hazards include slips and falls caused by wet or soapy floor and ladder surfaces; exposures to unguarded machinery such as pinch points, conveyors, packing machines, fillers, slicers and so forth; and exposure to electrical shock, especially in wet areas.

Aisles should be kept clear. Spilled materials should be cleaned immediately. Floors should be covered with non-slip material. Machinery should be adequately guarded and properly grounded, and ground fault circuit interrupters should be installed in wet areas. Proper lockout/tagout procedures are necessary to ensure that the possibility of unexpected start-up of machines and equipment will not cause injury to plant personnel.

Thermal burns can occur from steam lines and steam cleaning and from leaks or line breaks of high-pressure hydraulic equipment. Cryogenic “burns” can occur from exposure to liquid ammonia refrigerant. Good maintenance, spill and leak procedures and training can minimize the risk of burns.

Fires and explosions. Leaking ammonia systems (the lower explosive limit for ammonia is 16%; the upper explosive limit is 25%), dry milk powder and other flammable and combustible materials, welding and leaking high-pressure hydraulic equipment can all result in fires or explosions. An ammonia leak detector should be installed in areas with ammonia refrigeration systems. Flammable and combustible materials must be stored in closed metal receptacles. Spraying of milk powder should meet appropriate explosion-proof requirements. Only authorized personnel should perform welding. Compressed-gas cylinders should be regularly examined. Precautions should be taken to prevent the mixture of oxygen with flammable gases. Cylinders should be kept away from sources of heat.

Frostbite and cold stress can occur from exposure in the freezers and coolers. Adequate protective clothing, job rotation to warmer areas, warm lunchrooms and provision of hot drinks are recommended precautions.

Exposures to high noise levels can occur in processing, packaging, grinding and plastic model blow-moulding operations. Precautions include isolation of noisy equipment, proper maintenance, wearing of hearing protectors and a hearing conservation programme.

When entering confined spaces—for example, when entering sewer pits or cleaning tanks—ventilation must be provided. The area should be free from equipment, product, gas and personnel. Impellers, agitators and other equipment should be locked out.

Lifting of raw materials, pulling cases of product and packaging of products are associated with ergonomic problems. Solutions include mechanization and automation of manual operations.

A wide variety of chemical exposures can occur in the dairy products industry, including exposure to:

- ammonia vapours due to leaks in ammonia refrigeration systems

- corrosive chemicals (e.g., phosphoric acid used in the manufacture of cottage cheese, cleaning compounds, battery acids and so on)

- chlorine gas generated by inadvertent mixing of chlorinated sanitizer with acids

- hydrogen peroxide generated during ultra-high-temperature packaging operations

- ozone (and ultraviolet) exposure from UV light used in sanitizing operations

- carbon monoxide generated by the action of caustics reacting with milk sugar in clean-in-place (CIP) operations in milk evaporators

- carbon monoxide generated from propane or gasoline lift trucks, gas-fired heaters or gas-fired carton heat sealers

- chromium, nickel and other welding fumes and gases.

Employees should be trained and aware of handling practices for hazardous chemicals. Chemicals must be labelled properly. Standard operating procedures should be established and followed when cleaning up spills. LEV should be provided where necessary. Protective clothing, safety goggles, face shields, gloves and so on must be available for use and subsequently maintained. An eye wash facility and a quick drench shower should be accessible when working with corrosive materials.

Biological hazards. Employees may be exposed to a variety of bacteria and other microbiological hazards from the unprocessed raw milk and cheeses. Precautions include proper gloves, good personal hygiene and adequate sanitary facilities.

Poultry Processing

Economic Importance

Chicken and turkey production has increased dramatically in the United States since the 1980s. According to a US Department of Labor report this has been due to a change in consumer eating patterns (Hetrick 1994). A shift from red meat and pork to poultry is due in part to early medical studies.

The rise in consumption correspondingly has spurred an increase in the number of processing facilities and growers and a large rise in levels of employment. For example, the United States poultry industry experienced an increase in employment of 64% from 1980 to 1992. Productivity, in terms of pounds yield per worker, increased 3.1% due to mechanization or automation, as well as an increase in line speed, or birds per work hour. However, in comparison to red meat production, poultry production is still very labour intensive.

Globalization is also ocurring. There are production and processing facilities jointly owned by US investors and China and breeding, grow-out and processing facilities in China export product to Japan.

Typical poultry line workers are relatively unskilled, less educated, often members of minority groups and much lower paid than workers in the red meat and manufacturing sectors. Turnover is unusually high in certain aspects of the process. Live hanging, deboning and sanitation jobs are particularly stressful and have high turnover rates. Poultry processing by its nature is a largely rural-based industry found in economically depressed areas where there is a labour surplus. In the United States many processing plants have an increasing number of Spanish-speaking workers. These workers are somewhat transient, working in the processing plants part of the year. As the region’s crops near harvest, large segments of the workers move outdoors to pick and harvest.

Processing

Throughout the processing of chicken, rigid sanitation requirements must be met. This means that floors must be washed down periodically and often and that debris, parts and fat must be removed. Conveyors and processing equipment must be accessible, washed down and sanitized also. Condensation must not be allowed to accumulate on ceilings and equipment over exposed chicken; it must be wiped down with long-handled sponge mops. Overhead, unguarded radial-blade fans circulate the air in the processing areas.

Because of these sanitation requirements, guarded rotating equipment often cannot be silenced for noise-abatement purposes. Consequently, in the majority of the processing plant’s production areas, there is high noise exposure. A proper and well-run hearing conservation programme is necessary. Not only should initial audiograms and annual audiograms be given, but periodic dosimetry should also be done to document exposure. Purchased processing equipment should have as low an operating noise level as possible. Particular care needs to be taken in educating and training the workforce.

Receiving and live hang

The first step in processing involves off-loading of the modules and destacking the trays onto a conveyor system to the live hang area. Work here is in almost complete darkness, since this has a quieting effect on the birds. The conveyor belt with a tray is at about waist level. A hanger, with gloved hands, must reach and grab a bird by both thighs and hang its feet in a shackle on an overhead conveyor travelling in the opposite direction.

The hazards of the operation vary. Aside from the normal high level of noise, the darkness and the disorienting effect of opposite running conveyors, there is the dust from flapping birds, suddenly sprayed urine or faeces in the face and the possibility of a gloved finger being caught in a shackle. Conveyor lines need to be equipped with emergency stops. Hangers are constantly striking the backs of their hands against neighboring shackles as they pass overhead.

It is not uncommon for a hanger to be required to hang an average of 23 (or more) birds per minute. (Some positions on the hanger’s lines require more physical motions, perhaps 26 birds per minute.) Typically, seven hangers on one line may hang 38,640 birds in 4 hours before they get a break. If each bird weighs approximately 1.9 kg, each hanger conceivably lifts a total of 1,057 kg during the first 4 hours of his or her shift before a scheduled break. The hanger’s job is extremely stressful from both a physiological and psychological standpoint. Reducing workload could lessen this stress. The constant grabbing with both hands, pulling in and simultaneously lifting a flapping, scratching bird at shoulder or head height is stressful to the upper shoulder and neck.

The bird’s feathers and feet can easily scratch a hanger’s unprotected arms. The hangers are required to stand for prolonged periods of time on hard surfaces, which can lead to lower-back discomfort and pain. Proper footwear, possible use of a rump rest stand, protective eyewear, single-use disposable respirators, eyewash facilities and arm guards need to be available for the hanger’s protection.

An extremely important element to ensure the worker’s health is a proper job conditioning programme. For a period of up to 2 weeks, a new hanger must be acclimated to the conditions and slowly work up to a full shift. Another key ingredient is job rotation; after two hours of hanging birds, a hanger may be rotated to a less strenuous position. The division of labour among the hangers may be such that frequent short rest breaks in an air conditioned area are essential. Some plants have tried double crewing to allow crews to work for 20 minutes and rest for 20 minutes, to reduce the ergonomic stressors.

The health and comfort conditions for the hangers are somewhat dependent on the outside weather conditions and the conditions of the birds. If the weather is hot and dry, the birds carry with them dust and mites, which easily become airborne. If the weather is wet, the birds are harder to handle, the hangers’ gloves readily become wet and the hangers must work harder to hold onto the birds. There have been recent developments in reusable gloves with padded backs.

The impact of airborne particulates, feathers, mites and so on may be lessened with an efficient local exhaust ventilation (LEV) system. A balanced system using the push-pull principle, which uses down-draft cooling or heating, would benefit the workers. Additional cooling fans placed about would upset the efficiency of a balanced push-pull system.

Once hung in the shackles, the birds are conveyed to be initially stunned with electricity. The high voltage does not kill them but forces them to hang limply as a rotating wheel (bicycle tyre) guides their neck against a counter-rotating circular cutting blade. The neck is partially severed with the bird’s heart still beating to pump out the remainder of blood. There must be no blood in the carcass. A skilled worker must be positioned to slice those birds the kill machine misses. Because of the excessive amount of blood, the worker must be protected by wearing wet gear (a rain suit) and eye protection. Eye washing or flushing facilities must be made available also.

Dressing

The conveyor of birds then passes through a series of troughs or tanks of circulating hot water. These are called scalders. Water is usually heated by steam coils. The water is usually treated or chlorinated to kill bacteria. This phase allows the feathers to be easily removed. Care must be taken when working around the scalders. Often piping and valves are unprotected or poorly insulated and are contact points for burns.

As the birds exit the scalders, the carcass is passed through a U-shaped arrangement which pulls the head off. These parts are usually conveyed in flowing water troughs to a rendering (or by-products) area.

The line of carcasses passes through machines which have a series of rotating drums fixed with rubber fingers which remove the feathers. The feathers drop into a trench below with flowing water leading to the rendering area.

Consistency in bird weight is extremely critical to all aspects of the processing operation. If the weights vary from load to load, the production departments must adjust their processing equipment accordingly. For example, if lighter-weight birds follow heavier birds through the pickers, the rotating drums may not get all the feathers off. This causes rejects and rework. Not only does it add to the processing costs, but it causes additional ergonomic hand stresses, because someone has to hand pick the feathers using a pincer grip.

Once through the pickers, the line of birds passes through a singer. This is a gas-fired arrangement with three burners on each side, used to singe the fine hairs and feathers of each bird. Care must be taken to assure that the gas piping’s integrity is maintained due to the corrosive conditions of the picking or dressing area.

The birds then pass a hock cutter to sever the feet (or paws). The paws may be conveyed separately to a separate processing area of the plant for cleaning, sizing, sorting, chilling and packaging for the Asian market.

The birds must be rehung on different shackles before they enter the evisceration section of the plant. The shackles here are configured slightly differently, usually longer. Automation is readily available for this part of the process (see figure 1). However, workers need to provide back-up if a machine jams, to rehang dropped birds or to manually cut the feet off with pruning shears if the hock cutter fails to sever properly. From a processing and cost standpoint, it is critical that every shackle be filled. Rehang jobs involve exposure to highly repetitive motions and work involving awkward postures (raised elbows and shoulders). These workers are at increased risk for cumulative trauma disorders (CDTs).

Figure 1. Multi-cut machines reducing repetitive manual work

If a machine goes down or gets out of adjustment, a great deal of effort and stress is applied to get the lines running, sometimes at the expense of workers’ safety. When climbing to access points on the equipment, a maintenance worker may not take the time to get a ladder, instead stepping on top of wet, slippery equipment. Falls are a hazard. When any such equipment is purchased and installed, provisions must be made for easy access and maintenance. Lockout points and shut-offs need to be placed on each piece of equipment. The manufacturer must consider the environment and hazardous conditions under which their equipment must be maintained.

Evisceration

As the conveyor of birds pass out of dressing into a physically separate part of the process, they usually pass through another singer and then through a rotating circular blade which cuts out the oil sac or gland on each bird’s back at the base of the tail. Often such equipment’s blades are free rotating and need to guarded properly. Again, if the machine is not adjusted according to the bird’s weight, workers must be assigned to remove the sac by slicing it off with a knife.

Next, the conveyor line of birds passes through an automatic venting machine, which pushes up on the abdomen slightly while a blade cuts open the carcass without disturbing the bowel. The next machine or part of the process scoops into the cavity and pulls out the unbroken viscera for inspection. In the United States, the next few processing steps may involve government inspectors who check for growths, air sac disease, faecal contamination and a series of other abnormalities. Usually one inspector checks for only two or three items. If there is a high rate of abnormalities, the inspectors will slow the line down. Often the abnormalities do not cause total rejects, but specific parts of the birds may be washed or salvaged from the carcass to increase yield.

The more rejects, the more manual rework involving repetitive motion due to cutting, slicing and so on the production workers must perform. Government inspectors are usually seated on mandated adjustable elevating stands, whereas production workers called helpers, to their left and right, stand on grating or may use an adjustable sit stand if provided. Foot rests, adjustable height platforms, sit stands and job rotation will help relieve the physical and psychological stresses associated with this part of the process.

Once past the inspections, the viscera are sorted as they pass through a liver/heart or giblet harvester. The separated intestines, stomachs, spleens, kidneys and gall bladders are discarded and flushed into a flowing trench below. The heart and liver are separated and pumped to separate sorting conveyors, where workers inspect and pick by hand. The remaining intact livers and hearts are pumped or carried to a separate processing area to be bulk-packed by hand or later recombined in a giblet pack for stuffing by hand into the cavity of a whole bird for sale.

Once the carcass clears the harvester, the bird’s crop is augured out; each body cavity is probed by hand to pull out the remaining viscera and gizzard if necessary. The worker uses each hand in a separate bird as the conveyor passes in front. A suction device is often used to vacuum out any remaining lungs or kidneys. Frequently, due to the bird’s habit of ingesting small pebbles or pieces of litter during grow-out, a worker will reach into the bird’s cavity and receive painful puncture wounds in the tips of the fingers or under the finger nails.

The small wounds, if not treated properly, run the risk of serious infection since the bird’s cavity still is not cleaned of bacteria. Since tactile sensitivity is necessary for the job, there are no gloves yet available to prevent these frequent incidents. A tight-fitting surgeon’s type glove has been tried with some success. The line pace is so fast that it does not allow the worker to carefully insert his or her hands.

Finally, the carcass’s neck is removed by machine and harvested. The birds go through a bird washer which uses chlorinated spray to wash out excess viscera inside and outside each bird.

Throughout the dressing and evisceration, workers are exposed to high levels of noise, slippery floors and high ergonomic stress on kill, scissor and packaging jobs. According to a NIOSH study, rates of CTDs documented in poultry plants can range from 20 to 30% of workers (NIOSH 1990).

Chiller operations

Depending on the process, necks are pumped to a open-surfaced chiller tank with rotating arms, paddles or augers. These open tanks pose a serious threat to the safety of the worker during operation and need to be properly guarded by removable covers or grills. The tank’s cover must allow for visual inspection of the tank. If a cover is removed or lifted, interlocks must be provided to shut off the rotating arms or auger. The chilled necks are either bulk-packed for later processing or taken to the giblet wrap area for recombining and wrapping.

Once through evisceration, the conveyor lines of birds are either dropped into large, open-surfaced horizontal chilling tanks or, in Europe, pass through refrigerated, circulating air. These chillers are fitted with paddles which slowly rotate through the chiller, bringing down the bird’s body temperature. The chilled water is highly chlorinated (20 ppm or greater) and aerated for agitation. Bird carcass residence time in the chiller may be up to an hour.

Due to the high levels of free chlorine released and circulated, workers are exposed and may experience symptoms of eye and throat irritation, coughing and shortness of breath. NIOSH conducted several studies of eye and upper respiratory irritation in poultry processing plants, which recommended that levels of chlorine be monitored and controlled closely, that curtains be used to contain the liberated chlorine (or an enclosure of some sort should surround the open surface of the tank) and that an exhaust ventilation system should be installed (Sanderson, Weber and Echt 1995).

The resident time is critical and a matter of some controversy. Upon exiting evisceration, the carcass is not completely clean, and the skin pores and feather follicles are open and harbour disease-causing bacteria. The main purpose of the trip through the chiller is to chill the bird quickly to reduce spoilage. It does not kill bacteria, and the risk of cross contamination is a serious public health issue. Critics have called the chiller bath method “faecal soup”. From a profit perspective, a side benefit is the fact that the meat will absorb the chiller water like a sponge. It adds almost 8% to the market weight of the product (Linder 1996).

Upon exiting the chiller, the carcasses are deposited on a conveyor or shaker table. Specially trained workers called graders inspect the birds for bruises, skin breaks and so on and rehang the birds on separate shackle lines travelling in front of them. Downgraded birds may travel to different processes for parts recovery. Graders stand for prolonged periods handling chilled birds, which can result in numbness and hand pain. Gloves with liners are worn not only to protect the hands of workers from the chlorine residue, but also to provide some degree of warmth.

Cut-up

From grading the birds travel overhead to different processes, machines and lines in an area of the plant called second or further processing. Some machines are hand fed with two-handed trips. Other, more modern European equipment, at separate stations, may remove the thighs and wings and split the breast, without being touched by the worker. Again, consistency in bird size or weight is critical to the successful operation of this automated equipment. Rotating circular blades must be changed every day.

Skilled maintenance technicians and operators must be attentive to the equipment. Access to such equipment for adjustment, maintenance and sanitation needs to be frequent, requiring stairs, not ladders, and substantial work platforms. During blade changing, handling needs to be cautious because of the slipperiness due to fat build-up. Special cut- and slip-resistant gloves with the fingertips removed protect most of the hand, while the tips of the fingers can be used to manipulate the tools, bolts and nuts used for replacement.

Evolving consumer tastes have affected the production process. In some cases, the products (e.g., drumstick, thighs and breasts) are required to be skinless. Processing equipment has been developed to efficiently remove skin so workers do not have to do so by hand. However, as automated processing equipment is added and lines are rearranged, conditions become more crowded and awkward for workers to get around, manoeuvre floor jacks and carry totes, or plastic tubs, of iced product weighing over 27 kg over slippery, wet floors.

Depending on the customer demand and product mix sales, workers stand facing fixed-height conveyors, selecting and arranging product on plastic trays. The product travels in one direction or drops from a chute. The trays arrive on overhead conveyors, descending so the workers can grab a stack and set them in front for easy reach. Product defects may be either placed on a counter-flow conveyor below or hung in a shackle travelling in the opposite direction overhead. Workers stand for prolonged periods of time almost shoulder to shoulder, perhaps separated only by a tote into which defects or waste are dropped. Workers need to be provided with gloves, aprons and boots.

Some products may be bulk-packed in cartons covered with ice. This is called ice pack. Workers fill cartons by hand onto scales and manually transfer them to moving conveyors. Later in the ice pack room, ice is added, cartons recovered and the cartons removed and stacked manually on pallets ready for shipment.

Some workers in cut-up are also exposed to high levels of noise.

Deboning

If the carcass is destined for deboning, the product is tanked out in large aluminium bins or cardboard boxes (or gaylords) mounted on pallets. Breast meat must be aged for a certain number of hours before processing either by machine or hand. Fresh chicken is difficult to cut and trim by hand. From an ergonomic standpoint, meat ageing is a key point in helping to reduce repetitive motion injuries to the hand.

There are two methods used in deboning. In the manual method, once ready, carcasses with only the breast meat remaining are dumped into a hopper leading to a conveyor. This section of the line’s workers must handle each carcass and hold them against two horizontal, in-running textured skinner rolls. The carcass is rolled over the rolls as the skin is pulled away and down to a conveyor below. There is a risk of workers becoming inattentive or distracted and having their fingers pulled into the rollers. Emergency stop (E-stop) switches need to be provided within easy reach of either the free hand or knee. Gloves and loose clothing cannot be worn around such equipment. Aprons (worn snugly) and protective eyewear must be worn due to the possibility of bone chips or fragments being thrown.

The next step is performed by workers called nickers. They hold a carcass in one hand and make a slice along the keel (or breastbone) with the other. Sharp, short-bladed knives are normally used. Stainless steel mesh gloves are usually worn over a latex- or nitrile-gloved hand holding the carcass. Knives used for this operation do not need to have a sharp point. Protective eye wear needs to be worn.

The third step is performed by the keel pullers. This may be done manually or with a jig or fixture where the carcass is guided over an inexpensive “Y” fixture (made out of stainless steel rod stock) and pulled toward the worker. The working height of each fixture needs to be adjusted to the worker. The manual method simply requires the worker to use a pincer grip with a gloved hand and pull the keel bone out. Protective eyewear must be worn as described above.

The fourth step requires hand filleting. Workers stand shoulder to shoulder reaching for breast meat as it travels on shackle trays in front of them. There are certain techniques that must be observed for this part of the process. Proper job instruction and immediate correction when errors are observed are necessary. Workers are protected with a chain or mesh glove on one hand. In the other, they hold an extremely sharp knife (with a tip that may be too sharply pointed).

The work is fast paced, and workers who get behind are pressured to take short cuts, such as reaching across in front of the associate next to them or reaching for and/or stabbing a piece of meat travelling by out of their reach. Not only does the knife puncture reduce the quality of the product, but it also results in serious injury to fellow workers in the form of lacerations, which are often subject to infection. Protective plastic arm guards are available to prevent this frequent type of injury.

As the fillet meat is replaced on the conveyor shackle, it is picked off by the next section of workers, called trimmers. These workers must trim excess fat, missed skin and bones out of the meat using sharp and adjusted shears. Once trimmed, the finished product is either tray packed by hand or dropped into bulk bags and placed into cartons for restaurant use.

The second method of deboning involves automatic processing equipment developed in Europe. As with the manual method, bulk boxes or tanks of carcasses, sometimes with wings still attached, are loaded into a hopper and chute. Carcasses may then be picked manually and placed into segmented conveyors, or each carcass must be placed manually onto a shoe of the machine. The machine moves rapidly, carrying the carcass through a series of fingers (to remove skin), cutting blades and slitters. All that remains is a meatless carcass that is bulked out and used elsewhere. Most of the manual line’s positions are eliminated, except for the trimmers with scissors.

Deboning workers are exposed to serious ergonomic hazards from the forceful, repetitive nature of the work. In each of the deboning positions, especially filleters and trimmers, job rotation may be a key element to reducing ergonomic stresses. It must be understood that the position a worker rotates to must not use the same muscle group. A weak argument has been made that filleters and trimmers may rotate to each other’s position. This should not be allowed, because the same gripping, twisting and turning methods are used in the hand not holding the tool (knife or scissors). It may be argued that the muscles holding a knife loosely for twisting and turning while making fillet cuts are used differently when opening and closing scissors. However, twisting and turning of the hand is still required. Line speeds play a critical role in the onset of ergonomic disorders on these jobs.

Overwrap and chilling

After the product is tray packed in either cut-up or deboning, the trays are conveyed to another step in the process called overwrap. Workers retrieve specific product in trays and feed the trays into machines which apply and stretch printed clear wrap over the tray, tuck it under and pass the tray over a heat sealer. The tray may then pass through a washer, where it is retrieved and placed in a basket. The basket containing a particular product is placed on a conveyor where it passes into a chiller area. Trays are then sorted and stacked either manually or automatically.

Workers in the overwrap area stand for prolonged periods of time and are rotated so the hands they use to pick up the product trays are rotated. Normally the overwrap area is relatively dry. Cushioned mats would reduce leg and back fatigue.

Consumer demand, sales and marketing can create special ergonomic hazards. At certain times of the year, large trays are packed with several pounds of product for “convenience and cost savings”. This added weight has contributed to additional repetitive motion-related hand injuries simply because the process and conveying system is designed for one-handed pick-up. A worker simply does not have the strength necessary for repeated one-handed lifts of overweight trays.

The clear plastic wrap used in the packing may release slight amounts of monomer or other decomposition products when heated for sealing. If complaints arise concerning the fumes, the manufacturer or supplier of the film should be called in to help assess the problem. LEV may be necessary. The heat-sealing equipment needs to be maintained properly and its E-stops checked for proper operation at the beginning of each shift.

The chilling room or refrigeration area poses a different set of fire, safety and health risks. From a fire standpoint, the product packaging poses a risk since it is usually highly combustible polystyrene. The wall’s insulation is usually a polystyrene foam core. Chillers should be properly protected with pre-action dry sprinkler systems designed for extraordinary hazard. (Pre-action systems employ automatic sprinklers attached to piping systems containing dry air or nitrogen as well as a supplemental detection system installed in the same area as the sprinklers.)

Once the baskets of trays enter the chiller, workers must physically pick up a basket and lift it to shoulder height or higher to a stack on a dolly. After so many baskets are stacked, workers are required to assist each other to stack the baskets of product higher.

Temperatures in the chiller may run as low as –2 °C. Workers should be issued and instructed to wear multilayered clothing or “freezer suits” along with insulated safety-toed footwear. Dollies or stacks of baskets must be physically handled and pushed to various areas of the chiller until called for. Often, workers attempt to save time by pushing several stacks of trays at one time, which can result in muscle or lower-back strain.

Basket integrity is an important aspect of both product quality control and worker safety. If broken baskets are stacked with other full baskets stacked on top, the entire load becomes unstable and is easily tipped over. Product packages fall on the floor and become dirty or damaged, resulting in rework and extra manual handling by workers. Stacks of baskets may also fall on other workers.

When a particular product mix is called for, baskets may be destacked manually. Trays are loaded onto a conveyor with a scale which weighs them and attaches labels marked with the weight and codes for tracking purposes. Trays are packed manually in cartons or boxes sometimes lined with impermeable liners. Workers often have to reach for trays. As in the case of the overwrap process, larger, heavier packages of product can cause stress to the hands, arms and shoulders. Workers stand for prolonged periods in one spot. Antifatigue mats can reduce leg and lower-back stresses.

As the cartons of packages pass down a conveyor, liners may be heat sealed while CO2 is injected. This, along with continued refrigeration, prolongs product shelf life. Also, as the carton or case continues its progress, a scoop of CO2 nuggets (dry ice) is added to prolong shelf life on its way to a customer in a refrigerated trailer. However, CO2 has inherent hazards in enclosed areas. The nuggets may either be dropped by the chute or scooped out of a large, partially covered bin. Though the exposure limit (TLV) for CO2 is relatively high, and continuous monitors are readily available, workers also need to learn its hazards and symptoms and wear protective gloves and eye protection. Proper warning signs should also be posted in the area.

Cartons or cases of trayed product usually are sealed with hot-melt adhesive injected onto the cardboard. Painful contact burns are possible if adjustments, sensors and pressures are improper. Workers need to wear protective eyewear with side shields. The application and sealing equipment needs to be completely de-energized, with pressure bled off, before adjustments or repairs are made.

Once the cartons are sealed, they may either be manually lifted from the conveyor or run through an automatic palletizer or other remotely operated equipment. Due to the high rate of production, the potential for back injuries exists. This work is usually performed in a cold environment, which has a tendency to lead to strain injuries.

From an ergonomic standpoint, carton retrieval and stacking is easily automated, but investment and maintenance costs will be high.

Thigh deboning and ground chicken

No part of the chicken is wasted in modern poultry processing. Chicken thighs are bulk-packed, stored at or near freezing and then further processed, or deboned, either with scissors or pneumatically actuated hand-operated trimmers. Like the breast deboning operation, thigh deboning workers must remove excess fat and skin with scissors. Work area temperatures may be as low as 4 to 7 °C. Despite the fact that trimmers may wear liners with gloves, their hands are sufficiently chilled to restrict blood circulation, thereby magnifying the ergonomic stresses.

Once chilled, the thigh meat is further processed by adding flavours and grinding under a CO2 blanket. It is extruded as ground chicken patties or bulk.

Deli processing

Necks, backs and remaining carcasses from breast deboning are not wasted, but dumped into large paddle grinders or mixers, pumped through chilled mixers and extruded into bulk containers. This is usually sold or sent for further processing into what is called “chicken hot dogs” or “frankfurters”.

The recent development of convenience foods, which require little processing or preparation in the home, has resulted in high-value-added products for the poultry industry. Select pieces of meat from breast deboning are placed in a rotating vessel; solutions of flavouring and spices are then mixed under vacuum for a prescribed length of time. The meat gains not only flavour but weight as well, which improves the profit margin. The pieces are then packaged individually in trays. The trays are sealed under vacuum and packed off in small cases for shipment. This process is not time dependent, so workers are not subjected to the same line speeds as others in cut-up. The final product must be handled, inspected and packed carefully so it presents well in the stores.

Summary

Throughout poultry plants, wet processes and fat can create very dangerous floors, with a concurrent high risk of slipping and falling hazards. Proper cleaning of floors, adequate drainage (with protective barriers placed on all floor holes), proper footwear (waterproof and anti-slip) provided to workers and anti-slip floors are key to preventing these hazards.

In addition, high levels of noise are pervasive in poultry plants. Attention must be paid to engineering measures that decrease noise levels. Earplugs and replacements must be provided, as well as a full hearing conservation programme with annual hearing exams.

The poultry industry is an interesting blend of labour-intensive operations and high-tech processing. Human sweat and anguish still characterize the industry. The demands for increased yield and higher line speeds frequently overshadow efforts to properly train and protect the workers. As the technology improves to help eliminate repetitive-motion injuries or disorders, the equipment must be carefully maintained and calibrated by skilled technicians. The industry generally does not attract highly skilled technicians because of the mediocre pay levels, extremely stressful working conditions and often autocratic management, which also often resists positive changes that can be achieved with pro-active safety and health programming.

Meatpacking/Processing

Sources of meat slaughtered for human consumption include cattle, hogs, sheep, lambs and, in some countries, horses and camels. The size and production of slaughterhouses vary considerably. Except for very small operations located in rural areas, animals are slaughtered and processed in factory-type workplaces. These workplaces are usually subject to food-safety controls by the local government to prevent bacterial contamination that can cause foodborne illnesses in consumers. Examples of known pathogens in meat include salmonella and Escherichia coli. In these meat processing plants the work has become very specialized, with almost all the work being done on production disassembly lines where the meat moves on chains and conveyors, and each worker does only one operation. Almost all the cutting and processing is still done by workers. Production jobs can require between 10,000 and 20,000 cuts a day. In some large plants in the United States, for example, a few jobs, such as carcass splitting and bacon slicing, have been automated.

Slaughtering Process

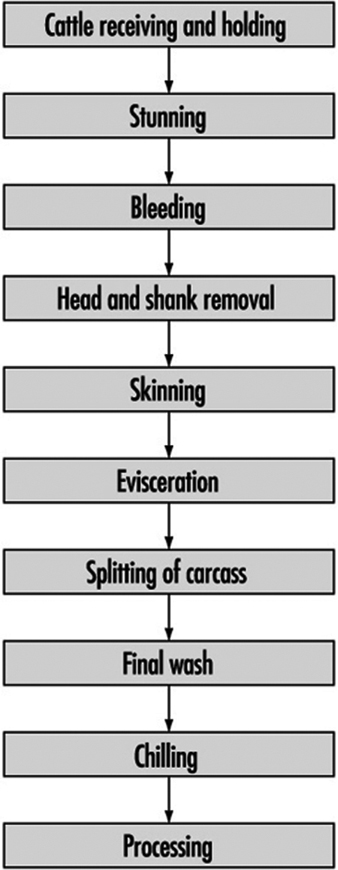

The animals are herded through a holding pen to slaughter (see figure 1). The animal must be stunned before being bled, unless slaughtered in accordance with Jewish or Muslim rites. Usually the animal is either knocked to an unconscious state with a bolt stunner gun or with a stunner gun utilizing compressed air that drives a pin into the head (the medulla oblongata) of the animal. After the stunning or “knocking” process, one of the animal’s hind legs is secured by a chain hooked onto an overhead conveyor which transfers the animal to the next room, where it is bled by “sticking” the jugular arteries in the neck with a sharp knife. The bleeding-out process follows, and the blood is drained through pipes for processing on floors below.

Figure 1. Beef slaughtering flow chart

The skin (hide) is removed by a series of cuts with knives (new air-powered knives are being used in the larger plants for some hide-removal operations) and the animal is then suspended by both hind legs from the overhead conveyor system. In some hog operations, the skin is not removed at this stage. Rather the hair is removed by sending the carcass through tanks of water heated to 58 ºC and then through a dehair machine that rubs the hair off the skin. Any remaining hair is removed by singeing and finally shaving.

The front legs and then the viscera (intestines) are removed. The head is then cut and dropped, and the carcass is split in half vertically along the spinal column. Hydraulic band saws are the usual tool for this job. After the carcass is split, it is rinsed with hot water, and may be steam vacuumed or even treated with a newly developed pasteurization process being introduced in some countries.

Government health inspectors usually inspect after the head removal, the viscera removal and the carcass splitting and final wash.

After this, the carcass, still hanging from the overhead conveyor system, moves to a cooler for chilling over the next 24 to 36 hours. The temperature is usually about 2 ºC to slow bacterial growth and inhibit spoilage.

Processing

Once chilled, the carcass halves are then cut into front and hind quarters. After this, pieces are further divided into prime cuts, depending on customer specifications. Some quarters are processed for delivery as the front or hind quarters without any further significant trimming. These pieces can weigh from 70 to 125 kg. Many plants (in the United States, the majority of plants) conduct further processing of the meat (some plants do only this processing and receive their meat from slaughterhouses). Products from these plants are shipped in boxes weighing approximately 30 kg.

Cutting is done by hand or powered saws, depending on the cuts, usually following trimming operations to remove skin. Many plants also use large grinders for grinding hamburger and other ground meats. Further processing can involve equipment including bacon presses, ham tumblers and extruders, bacon slicers, electric meat tenderizers and smoke houses. Conveyor belts and screw augers are often used to transport product. Processing areas are also kept cool, with temperatures in the 4 °C range.

Offal meats, such as liver, hearts, sweetbreads, tongues and glands, are processed in a separate area.

Many plants also treat the hides before sending them to a tanner.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Meatpacking has one of the highest rates of injury of all industries. A worker may be injured by the moving animals as they are led through the holding pen into the plant. Adequate training must be given to workers on handling live animals, and minimal worker exposure in this process is advised. Stunner guns may prematurely or inadvertently discharge while workers try to still the animals. Falling animals and nervous system reactions in stunned cattle that cause jerking present hazards to workers in the area. Further, many operations utilize a series of hooks, chains and conveyor tram rails to move the product between processing steps, posing the hazard of falling carcasses and product.

Adequate maintenance of all equipment is necessary, especially equipment used to move meat. Such equipment must be checked frequently and repaired as needed. Adequate safeguards for knocking guns, such as safety switches and making sure there is no blow back, must be taken. Workers involved in knocking and sticking operations must be trained on the hazards of this job, as well as provided with guarded knives and protective equipment to prevent injury. For sticking operations this includes arm guards, mesh gloves and special guarded knives.

Both in the slaughter and further processing of animals, hand knives and mechanical cutting devices are used. Mechanical cutting devices include head splitters, bone splitters, snout pullers, electric band and circular saws, electric- or air-powered circular-blade knives, grinding machines and bacon processors. These types of operations have a high rate of injury, from knife cuts to amputations, because of the speed at which workers operate, the inherent danger of the tools being used and the often slippery nature of the product from fat and wet processes. Workers can be cut by their own knives and by other workers’ knives during the butchering process (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Cutting and sorting meat without protective equipment in a Thai meat packing factory

The above operations require protective equipment, including protective helmets, footwear, mesh gloves and aprons, wrist and forearm guards and waterproof aprons. Protective goggles may be required during boning, trimming and cutting operations to prevent foreign objects from entering workers’ eyes. Metal mesh gloves must not be used while operating any type of powered or electrical saw. Powered saws and tools must have proper safety guards, such as blade guards and shut-off switches. Unguarded sprockets and chains, conveyor belts and other equipment can pose a hazard. All such equipment must be properly guarded. Hand knives should also have guards to prevent the hand holding the knife from slipping over the blade. Training and adequate spacing between workers is necessary to conduct operations safely.

Workers maintaining, cleaning or unjamming equipment such as conveyor belts, bacon processors, meat grinders and other processing equipment are subject to the hazard of the inadvertent start-up of equipment. This has caused fatalities and amputations. Some equipment is cleaned while running, subjecting workers to the hazard of getting caught in the machinery.

Workers must be trained in safety lockout/tagout procedures. Implementation of procedures that prevent workers from fixing, cleaning or unjamming equipment until the equipment is off and locked out will prevent injuries. Workers involved in locking out pieces of equipment must be trained on procedures for neutralizing all energy sources.

Wet and treacherously slippery floors and stairs throughout the plant pose a serious hazard to workers. Elevated work platforms also pose a falling hazard. Workers must be provided with safety shoes with non-slip soles. Non-slip floor surfaces and roughened floors, approved by local health agencies, are available and should be used on floors and stairways. Adequate drainage in wet areas must be provided, along with proper and adequate housekeeping of floors during production hours to minimize wet and slippery surfaces. All elevated surfaces must also be properly equipped with guard rails both to prevent workers from accidental falls and to prevent worker contact and materials falling from conveyors. Toe boards should also be used on elevated platforms, where necessary. Guardrails should also be used on stairways on the production floor to prevent slipping.

The combination of wet working conditions and elaborate electrical wiring poses a hazard of electrocution to workers. All equipment must be properly grounded. Electrical outlet boxes should be provided with covers which effectively protect against accidental contact. All electrical wiring should be checked periodically for cracking, fraying or other defects, and all electrical equipment should be grounded. Ground fault circuit interrupters should be used where possible.