74. Mining and Quarrying

Chapter Editors: James R. Armstrong and Raji Menon

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Mining: An Overview

Norman S. Jennings

Exploration

William S. Mitchell and Courtney S. Mitchell

Types of Coal Mining

Fred W. Hermann

Techniques in Underground Mining

Hans Hamrin

Underground Coal Mining

Simon Walker

Surface Mining Methods

Thomas A. Hethmon and Kyle B. Dotson

Surface Coal Mining Management

Paul Westcott

Processing Ore

Sydney Allison

Coal Preparation

Anthony D. Walters

Ground Control in Underground Mines

Luc Beauchamp

Ventilation and Cooling in Underground Mines

M.J. Howes

Lighting in Underground Mines

Don Trotter

Personal Protective Equipment in Mining

Peter W. Pickerill

Fires and Explosions in Mines

Casey C. Grant

Detection of Gases

Paul MacKenzie-Wood

Emergency Preparedness

Gary A. Gibson

Health Hazards of Mining and Quarrying

James L. Weeks

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Design air quantity factors

2. Clothing-corrected air cooling powers

3. Comparison of mine light sources

4. Heating of coal-hierarchy of temperatures

5. Critical elements/sub-elements of emergency preparedness

6. Emergency facilities, equipment & materials

7. Emergency preparedness training matrix

8. Examples of horizontal auditing of emergency plans

9. Common names & health effects of hazardous gases

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Mining: An Overview

Minerals and mineral products are the backbone of most industries. Some form of mining or quarrying is carried out in virtually every country in the world. Mining has important economic, environmental, labour and social effects—both in the countries or regions where it is carried out and beyond. For many developing countries mining accounts for a significant proportion of GDP and, often, for the bulk of foreign exchange earnings and foreign investment.

The environmental impact of mining can be significant and long-lasting. There are many examples of good and bad practice in the management and rehabilitation of mined areas. The environmental effect of the use of minerals is becoming an important issue for the industry and its workforce. The debate on global warming, for example, could affect the use of coal in some areas; recycling lessens the amount of new material required; and the increasing use of non-mineral materials, such as plastics, affects the intensity of use of metals and minerals per unit of GDP.

Competition, declining mineral grades, higher treatment costs, privatization and restructuring are each putting pressure on mining companies to reduce their costs and increase their productivity. The high capital intensity of much of the mining industry encourages mining companies to seek the maximum use of their equipment, calling in turn for more flexible and often more intensive work patterns. Employment is falling in many mining areas due to increased productivity, radical restructuring and privatization. These changes not only affect mineworkers who must find alternative employment; those remaining in the industry are required to have more skills and more flexibility. Finding the balance between the desire of mining companies to cut costs and those of workers to safeguard their jobs has been a key issue throughout the world of mining. Mining communities must also adapt to new mining operations, as well as to downsizing or closure.

Mining is often considered to be a special industry involving close-knit communities and workers doing a dirty, dangerous job. Mining is also a sector where many at the top—managers and employers—are former miners or mining engineers with wide, first-hand experience of the issues that affect their enterprises and workforces. Moreover, mineworkers have often been the elite of industrial workers and have frequently been at the forefront when political and social changes have taken place faster than was envisaged by the government of the day.

About 23 billion tonnes of minerals, including coal, are produced each year. For high-value minerals, the quantity of waste produced is many times that of the final product. For example, each ounce of gold is the result of dealing with about 12 tonnes of ore; each tonne of copper comes from about 30 tonnes of ore. For lower value materials (e.g., sand, gravel and clay)—which account for the bulk of the material mined—the amount of waste material that can be tolerated is minimal. It is safe to assume, however, that the world’s mines must produce at least twice the final amount required (excluding the removal of surface “overburden”, which is subsequently replaced and therefore handled twice). Globally, therefore, some 50 billion tonnes of ore are mined each year. This is the equivalent of digging a 1.5 metre deep hole the size of Switzerland every year.

Employment

Mining is not a major employer. It accounts for about 1% of the world’s workforce—some 30 million people, 10 million of whom produce coal. However, for every mining job there is at least one job that is directly dependent on mining. In addition, it is estimated that at least 6 million people not included in the above figure work in small-scale mines. When one takes dependants into account, the number of people relying on mining for a living is likely to be about 300 million.

Safety and Health

Mineworkers face a constantly changing combination of workplace circumstances, both daily and throughout the work shift. Some work in an atmosphere without natural light or ventilation, creating voids in the earth by removing material and trying to ensure that there will be no immediate reaction from the surrounding strata. Despite the considerable efforts in many countries, the toll of death, injury and disease among the world’s mineworkers means that, in most countries, mining remains the most hazardous occupation when the number of people exposed to risk is taken into account.

Although only accounting for 1% of the global workforce, mining is responsible for about 8% of fatal accidents at work (around 15,000 per year). No reliable data exist as far as injuries are concerned, but they are significant, as is the number of workers affected by occupational diseases (such as pneumoconioses, hearing loss and the effects of vibration) whose premature disability and even death can be directly attributed to their work.

The ILO and Mining

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has been dealing with labour and social problems of the mining industry since its early days, making considerable efforts to improve work and life of those in the mining industry—from the adoption of the Hours of Work (Coal Mines) Convention (No. 31) in 1931 to the Safety and Health in Mines Convention (No. 176), which was adopted by the International Labour Conference in 1995. For 50 years tripartite meetings on mining have addressed a variety of issues ranging from employment, working conditions and training to occupational safety and health and industrial relations. The results are over 140 agreed conclusions and resolutions, some of which have been used at the national level; others have triggered ILO action—including a variety of training and assistance programmes in member States. Some have led to the development of codes of safety practice and, most recently, to the new labour standard.

In 1996 a new system of shorter, more focused tripartite meetings was introduced, in which topical mining issues will be identified and discussed in order to address the issues in a practical way in the countries and regions concerned, at the national level and by the ILO. The first of these, in 1999, will deal with social and labour issues of small-scale mining.

Labour and social issues in mining cannot be separated from other considerations, whether they be economic, political, technical or environmental. While there can be no model approach to ensuring that the mining industry develops in a way that benefits all those involved, there is clearly a need that it should do so. The ILO is doing what it can to assist in the labour and social development of this vital industry. But it cannot work alone; it must have the active involvement of the social partners in order to maximize its impact. The ILO also works closely with other international organizations, bringing the social and labour dimension of mining to their attention and collaborating with them as appropriate.

Because of the hazardous nature of mining, the ILO has been always deeply concerned with the improvement of occupational safety and health. The ILO’s International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconioses is an internationally recognized tool for recording systematically radiographic abnormalities in the chest provoked by the inhalation of dusts. Two codes of practice on safety and health deal exclusively with underground and surface mines; others are relevant to the mining industry.

The adoption of the Convention on Safety and Health in Mines in 1995, which has set the principle for national action on the improvement of working conditions in the mining industry, is important because:

- Special hazards are faced by mineworkers.

- The mining industry in many countries is assuming increasing importance.

- Earlier ILO standards on occupational safety and health, as well as the existing legislation in many countries, are inadequate to deal with the specific needs of mining.

The first two ratifications of the Convention occurred in mid-1997; it will enter into force in mid-1998.

Training

In recent years the ILO has carried out a variety of training projects aimed at improving the safety and health of miners through greater awareness, improved inspection and rescue training. The ILO’s activities to date have contributed to progress in many countries, bringing national legislation into conformity with international labour standards and raising the level of occupational safety and health in the mining industry.

Industrial relations and employment

The pressure to improve productivity in the face of intensified competition can sometimes result in basic principles of freedom of association and collective bargaining being called into question when enterprises perceive that their profitability or even survival is in doubt. But sound industrial relations based on the constructive application of those principles can make an important contribution to productivity improvement. This issue was examined at length at a meeting in 1995. An important point to emerge was the need for close consultation between the social partners for any necessary restructuring to be successful and for the mining industry as a whole to obtain lasting benefits. Also, it was agreed that new flexibility of work organization and work methods should not jeopardize workers’ rights, nor adversely affect health and safety.

Small-scale Mining

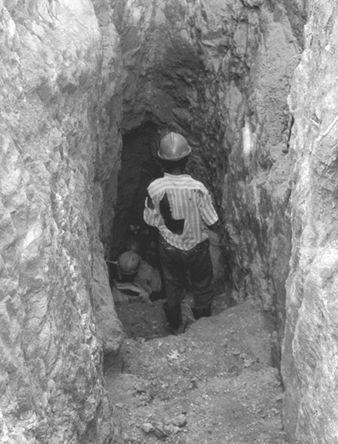

Small-scale mining falls into two broad categories. The first is the mining and quarrying of industrial and construction materials on a small scale, operations that are mostly for local markets and present in every country (see figure 1). Regulations to control and tax them are often in place but, as for small manufacturing plants, lack of inspection and lax enforcement mean that informal or illegal operations persist.

Figure 1. Small-scale stone quarry in West Bengal

The second category is the mining of relatively high-value minerals, notably gold and precious stones (see figure 2). The output is generally exported, through sales to approved agencies or through smuggling. The size and character of this type of small-scale mining have made what laws there are inadequate and impossible to apply.

Figure 2. Small-scale gold mine in Zimbabwe

Small-scale mining provides considerable employment, particularly in rural areas. In some countries, many more people are employed in small-scale, often informal, mining than in the formal mining sector. The limited data that exist suggest that upwards of six million people engage in small-scale mining. Unfortunately, however, many of these jobs are precarious and are far from conforming with international and national labour standards. Accident rates in small-scale mines are routinely six of seven times higher than in larger operations, even in industrialized countries. Illnesses, many due to unsanitary conditions are common at many sites. This is not to say that there are no safe, clean, small-scale mines—there are, but they tend to be a small minority.

A special problem is the employment of children. As part of its International Programme for the Elimination of Child Labour, the ILO is undertaking projects in several countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America to provide educational opportunities and alternative income-generating prospects to remove children from coal, gold and gemstone mines in three regions in these countries. This work is being coordinated with the international mineworkers union (ICEM) and with local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and government agencies.

NGOs have also worked hard and effectively at the local level to introduce appropriate technologies to improve efficiency and mitigate the health and environmental impact of small-scale mining. Some international governmental organizations (IGOs) have undertaken studies and developed guidelines and programmes of action. These address child labour, the role of women and indigenous people, taxation and land title reform, and environmental impact but, so far, they appear to have had little discernible effect. It should be noted, however, that without the active support and participation of governments, the success of such efforts is problematic.

Also, for the most part, there seems to be little interest among small-scale miners in using cheap, readily-available and effective technology to mitigate health and environmental effects, such as retorts to recapture mercury. There is often no incentive to do so, since the cost of mercury is not a constraint. Moreover, particularly in the case of itinerant miners, there is frequently no long-term interest in preserving the land for use after the mining has ceased. The challenge is to show small-scale miners that there are better ways to go about their mining that would not unduly constrain their activities and be better for them in terms of health and wealth, better for the land and better for the country. The “Harare Guidelines”, developed at the 1993 United Nations Interregional Seminar on Guidelines for the Development of Small/Medium Scale Mining, provide guidance for governments and for development agencies in tackling the different issues in a complete and coordinated way. The absence of involvement by employers’ and workers’ organizations in most small-scale mining activity puts a special responsibility on the government in bringing small-scale mining into the formal sector, an action that would improve the lot of small-scale miners and markedly increase the economic and social benefits of small-scale mining. Also, at an international roundtable in 1995 organized by the World Bank, a strategy for artisanal mining that aims to minimize negative side effects—including poor safety and health conditions of this activity—and maximize the socio-economic benefits was developed.

The Safety and Health in Mines Convention and its accompanying Recommendation (No. 183) set out in detail an internationally agreed benchmark to guide national law and practice. It covers all mines, providing a floor—the minimum safety requirement against which all changes in mine operations should be measured. The provisions of the Convention are already being included in new mining legislation and in collective agreements in several countries and the minimum standards it sets are exceeded by the safety and health regulations already promulgated in many mining countries. It remains for the Convention to be ratified in all countries (ratification would give it the force of law), to ensure that the appropriate authorities are properly staffed and funded so that they can monitor the implementation of the regulations in all sectors of the mining industry. The ILO will also monitor the application of the Convention in countries that ratify it.

Exploration

Mineral exploration is the precursor to mining. Exploration is a high-risk, high-cost business that, if successful, results in the discovery of a mineral deposit that can be mined profitably. In 1992, US$1.2 billion was spent worldwide on exploration; this increased to almost US$2.7 billion in 1995. Many countries encourage exploration investment and competition is high to explore in areas with good potential for discovery. Almost without exception, mineral exploration today is carried out by interdisciplinary teams of prospectors, geologists, geophysicists and geochemists who search for mineral deposits in all terrain throughout the world.

Mineral exploration begins with a reconnaissance or generative stage and proceeds through a target evaluation stage, which, if successful, leads to advanced exploration. As a project progresses through the various stages of exploration, the type of work changes as do health and safety issues.

Reconnaissance field work is often conducted by small parties of geoscientists with limited support in unfamiliar terrain. Reconnaissance may comprise prospecting, geologic mapping and sampling, wide-spaced and preliminary geochemical sampling and geophysical surveys. More detailed exploration commences during the target testing phase once land is acquired through permit, concession, lease or mineral claims. Detailed field work comprising geologic mapping, sampling and geophysical and geochemical surveys requires a grid for survey control. This work frequently yields targets that warrant testing by trenching or drilling, entailing the use of heavy equipment such as back-hoes, power shovels, bulldozers, drills and, occasionally, explosives. Diamond, rotary or percussion drill equipment may be truck-mounted or may be hauled to the drill site on skids. Occasionally helicopters are used to sling drills between drill sites.

Some project exploration results will be sufficiently encouraging to justify advanced exploration requiring the collection of large or bulk samples to evaluate the economic potential of a mineral deposit. This may be accomplished through intensive drilling, although for many mineral deposits some form of trenching or underground sampling may be necessary. An exploration shaft, decline or adit may be excavated to gain underground access to the deposit. Although the actual work is carried out by miners, most mining companies will ensure that an exploration geologist is responsible for the underground sampling programme.

Health and Safety

In the past, employers seldom implemented or monitored exploration safety programmes and procedures. Even today, exploration workers frequently have a cavalier attitude towards safety. As a result, health and safety issues may be overlooked and not considered an integral part of the explorer’s job. Fortunately, many mining exploration companies now strive to change this aspect of the exploration culture by requiring that employees and contractors follow established safety procedures.

Exploration work is often seasonal. Consequently there are pressures to complete work within a limited time, sometimes at the expense of safety. In addition, as exploration work progresses to later stages, the number and variety of risks and hazards increase. Early reconnaissance field work requires only a small field crew and camp. More detailed exploration generally requires larger field camps to accommodate a greater number of employees and contractors. Safety issues—especially training on personal health issues, camp and worksite hazards, the safe use of equipment and traverse safety—become very important for geoscientists who may not have had previous field work experience.

Because exploration work is often carried out in remote areas, evacuation to a medical treatment centre may be difficult and may depend on weather or daylight conditions. Therefore, emergency procedures and communications should be carefully planned and tested before field work commences.

While outdoor safety may be considered common sense or “bush sense”, one should remember that what is considered common sense in one culture may not be so considered in another culture. Mining companies should provide exploration employees with a safety manual that addresses the issues of the regions where they work. A comprehensive safety manual can form the basis for camp orientation meetings, training sessions and routine safety meetings throughout the field season.

Preventing personal health hazards

Exploration work subjects employees to hard physical work that includes traversing terrain, frequent lifting of heavy objects, using potentially dangerous equipment and being exposed to heat, cold, precipitation and perhaps high altitude (see figure 1). It is essential that employees be in good physical condition and in good health when they begin field work. Employees should have up-to-date immunizations and be free of communicable diseases (e.g., hepatitis and tuberculosis) that may rapidly spread through a field camp. Ideally, all exploration workers should be trained and certified in basic first aid and wilderness first-aid skills. Larger camps or worksites should have at least one employee trained and certified in advanced or industrial first-aid skills.

Figure 1. Drilling in mountains in British Columbia, Canada, with a light Winkie drill

William S. Mitchell

Outdoor workers should wear suitable clothing that protects them from extremes of heat, cold and rain or snow. In regions with high levels of ultraviolet light, workers should wear a broad-brimmed hat and use a sunscreen lotion with a high sun protection factor (SPF) to protect exposed skin. When insect repellent is required, repellent that contains DEET (N,N-diethylmeta-toluamide) is most effective in preventing bites from mosquitoes. Clothing treated with permethrin helps protect against ticks.

Training. All field employees should receive training in such topics as lifting, the correct use of approved safety equipment (e.g., safety glasses, safety boots, respirators, appropriate gloves) and health precautions needed to prevent injury due to heat stress, cold stress, dehydration, ultraviolet light exposure, protection from insect bites and exposure to any endemic diseases. Exploration workers who take assignments in developing countries should educate themselves about local health and safety issues, including the possibility of kidnapping, robbery and assault.

Preventive measures for the campsite

Potential health and safety issues will vary with the location, size and type of work performed at a camp. Any field campsite should meet local fire, health, sanitation and safety regulations. A clean, orderly camp will help reduce accidents.

Location. A campsite should be established as close as safely possible to the worksite to minimize travel time and exposure to dangers associated with transportation. A campsite should be located away from any natural hazards and take into consideration the habits and habitat of wild animals that may invade a camp (e.g., insects, bears and reptiles). Whenever possible, camps should be near a source of clean drinking water (see figure 2). When working at very high altitude, the camp should be located at a lower elevation to help prevent altitude sickness.

Figure 2. Summer field camp, Northwest Territories, Canada

William S. Mitchell

Fire control and fuel handling. Camps should be set up so that tents or structures are well spaced to prevent or reduce the spread of fire. Fire-fighting equipment should be kept in a central cache and appropriate fire extinguishers kept in kitchen and office structures. Smoking regulations help prevent fires both in camp and in the field. All workers should participate in fire drills and know the plans for fire evacuation. Fuels should be accurately labelled to ensure that the correct fuel is used for lanterns, stoves, generators and so on. Fuel caches should be located at least 100 m from camp and above any potential flood or tide level.

Sanitation. Camps require a supply of safe drinking water. The source should be tested for purity, if required. When necessary, drinking water should be stored in clean, labelled containers separate from non-potable water. Food shipments should be examined for quality upon arrival and immediately refrigerated or stored in containers to prevent invasions from insects, rodents or larger animals. Handwashing facilities should be located near eating areas and latrines. Latrines must conform to public health standards and should be located at least 100 m away from any stream or shoreline.

Camp equipment, field equipment and machinery. All equipment (e.g., chain saws, axes, rock hammers, machetes, radios, stoves, lanterns, geophysical and geochemical equipment) should be kept in good repair. If firearms are required for personal safety from wild animals such as bears, their use must be strictly controlled and monitored.

Communication. It is important to establish regular communication schedules. Good communication increases morale and security and forms a basis for an emergency response plan.

Training. Employees should be trained in the safe use all equipment. All geophysicists and helpers should be trained to use ground (earth) geophysical equipment that may operate at high current or voltage. Additional training topics should include fire prevention, fire drills, fuel handling and firearms handing, when relevant.

Preventive measures at the worksite

The target testing and advanced stages of exploration require larger field camps and the use of heavy equipment at the worksite. Only trained workers or authorized visitors should be permitted onto worksites where heavy equipment is operating.

Heavy equipment. Only properly licensed and trained personnel may operate heavy equipment. Workers must be constantly vigilant and never approach heavy equipment unless they are certain the operator knows where they are, what they intend to do and where they intend to go.

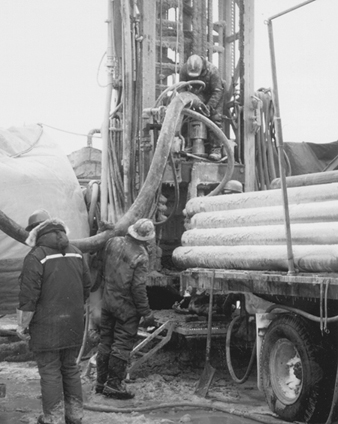

Figure 3. Truck-mounted drill in Australia

Williams S. Mitchll

Drill rigs. Crews should be fully trained for the job. They must wear appropriate personal protective equipment (e.g., hard hats, steel-toed boots, hearing protection, gloves, goggles and dust masks) and avoid wearing loose clothing that may become caught in machinery. Drill rigs should comply with all safety requirements (e.g., guards that cover all moving parts of machinery, high pressure air hoses secured with clamps and safety chains) (see figure 3). Workers should be aware of slippery, wet, greasy, or icy conditions underfoot and the drill area kept as orderly as possible (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Reverse circulation drilling on a frozen lake in Canada

William S. Mitchell

Excavations. Pits and trenches should be constructed to meet safety guidelines with support systems or the sides cut back to 45º to deter collapse. Workers should never work alone or remain alone in a pit or trench, even for a short period of time, as these excavations collapse easily and may bury workers.

Explosives. Only trained and licensed personnel should handle explosives. Regulations for handling, storage and transportation of explosives and detonators should be carefully followed.

Preventive measures in traversing terrain

Exploration workers must be prepared to cope with the terrain and climate of their field area. The terrain may include deserts, swamps, forests, or mountainous terrain of jungle or glaciers and snowfields. Conditions may be hot or cold and dry or wet. Natural hazards may include lightning, bush fires, avalanches, mudslides or flash floods and so on. Insects, reptiles and/or large animals may present life-threatening hazards.

Workers must not take chances or place themselves in danger to secure samples. Employees should receive training in safe traversing procedures for the terrain and climate conditions where they work. They need survival training to recognize and combat hypothermia, hyperthermia and dehydration. Employees should work in pairs and carry enough equipment, food and water (or have access in an emergency cache) to enable them to spend an unexpected night or two out in the field if an emergency situation arises. Field workers should maintain routine communication schedules with the base camp. All field camps should have established and tested emergency response plans in case field workers need rescuing.

Preventive measures in transportation

Many accidents and incidents occur during transportation to or from an exploration worksite. Excessive speed and/or alcohol consumption while driving vehicles or boats are relevant safety issues.

Vehicles. Common causes of vehicle accidents include hazardous road and/or weather conditions, overloaded or incorrectly loaded vehicles, unsafe towing practices, driver fatigue, inexperienced drivers and animals or people on the road—especially at night. Preventive measures include following defensive driving techniques when operating any type of vehicle. Drivers and passengers of cars and trucks must use seatbelts and follow safe loading and towing procedures. Only vehicles that can safely operate in the terrain and weather conditions of the field area, e.g., 4-wheel drive vehicles, 2-wheel motor bikes, all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) or snowmobiles should be used (see figure 5). Vehicles must have regular maintenance and contain adequate equipment including survival gear. Protective clothing and a helmet are required when operating ATVs or 2-wheel motor bikes.

Figure 5. Winter field transportation in Canada

William S. Mitchell

Aircraft. Access to remote sites frequently depends on fixed wing aircraft and helicopters (see figure 6). Only charter companies with well-maintained equipment and a good safety record should be engaged. Aircraft with turbine engines are recommended. Pilots must never exceed the legal number of allowable flight hours and should never fly when fatigued or be asked to fly in unacceptable weather conditions. Pilots must oversee the proper loading of all aircraft and comply with payload restrictions. To prevent accidents, exploration workers must be trained to work safely around aircraft. They must follow safe embarkation and loading procedures. No one should walk in the direction of the propellers or rotor blades; they are invisible when moving. Helicopter landing sites should be kept free of loose debris that may become airborne projectiles in the downdraft of rotor blades.

Figure 6. Unloading field supplies from Twin Otter, Northwest Territories, Canada

William S. Mitchell

Slinging. Helicopters are often used to move supplies, fuel, drill and camp equipment. Some major hazards include overloading, incorrect use of or poorly maintained slinging equipment, untidy worksites with debris or equipment that may be blown about, protruding vegetation or anything that loads may snag on. In addition, pilot fatigue, lack of personnel training, miscommunication between parties involved (especially between the pilot and groundman) and marginal weather conditions increase the risks of slinging. For safe slinging and to prevent accidents, all parties must follow safe slinging procedures and be fully alert and well briefed with mutual responsibilities clearly understood. The sling cargo weight must not exceed the lifting capacity of the helicopter. Loads should be arranged so they are secure and nothing will slip out of the cargo net. When slinging with a very long line (e.g., jungle, mountainous sites with very tall trees), a pile of logs or large rocks should be used to weigh down the sling for the return trip because one should never fly with empty slings or lanyards dangling from the sling hook. Fatal accidents have occurred when unweighted lanyards have struck the helicopter tail or main rotor during flight.

Boats. Workers who rely on boats for field transportation on coastal waters, mountain lakes, streams or rivers may face hazards from winds, fog, rapids, shallows, and submerged or semi-submerged objects. To prevent boating accidents, operators must know and not exceed the limitations of their boat, their motor and their own boating capabilities. The largest, safest boat available for the job should be used. All workers should wear a good quality personal flotation device (PFD) whenever travelling and/or working in small boats. In addition, all boats must contain all legally required equipment plus spare parts, tools, survival and first aid equipment and always carry and use up-to-date charts and tide tables.

Types of Coal Mining

The rationale for selecting a method for mining coal depends on such factors as topography, geometry of the coal seam, geology of the overlying rocks and environmental requirements or restraints. Overriding these, however, are the economic factors. They include: availability, quality and costs of the required work force (including the availability of trained supervisors and managers); adequacy of housing, feeding and recreational facilities for the workers (especially when the mine is located at a distance from a local community); availability of the necessary equipment and machinery and of workers trained to operate it; availability and costs of transportation for workers, necessary supplies, and for getting the coal to the user or purchaser; availability and the cost of the necessary capital to finance the operation (in local currency); and the market for the particular type of coal to be extracted (i.e., the price at which it may be sold). A major factor is the stripping ratio, that is, the amount of overburden material to be removed in proportion to the amount of coal that can be extracted; as this increases, the cost of mining becomes less attractive. An important factor, especially in surface mining, that, unfortunately, is often overlooked in the equation, is the cost of restoring the terrain and the environment when the mining operation is closed down.

Health and Safety

Another critical factor is the cost of protecting the health and safety of the miners. Unfortunately, particularly in small-scale operations, instead of being weighed in deciding whether or how the coal should be extracted, the necessary protective measures are often ignored or short-changed.

Actually, although there are always unsuspected hazards—they may come from the elements rather than the mining operations—any mining operation can be safe providing there is a commitment from all parties to a safe operation.

Surface Coal Mines

Surface mining of coal is performed by a variety of methods depending on the topography, the area in which the mining is being undertaken and environmental factors. All methods involve the removal of overburden material to allow for the extraction of the coal. While generally safer than underground mining, surface operations do have some specific hazards that must be addressed. Prominent among these is the use of heavy equipment which, in addition to accidents, may involve exposure to exhaust fumes, noise and contact with fuel, lubricants and solvents. Climatic conditions, such as heavy rain, snow and ice, poor visibility and excessive heat or cold may compound these hazards. When blasting is required to break up rock formations, special precautions in the storage, handling and use of explosives are required.

Surface operations require the use of huge waste dumps to store overburden products. Appropriate controls must be implemented to prevent dump failure and to protect the employees, the general public and the environment.

Underground Mining

There is also a variety of methods for underground mining. Their common denominator is the creation of tunnels from the surface to the coal seam and the use of machines and/or explosives to extract the coal. In addition to the high frequency of accidents—coal mining ranks high on the list of hazardous workplaces wherever statistics are maintained—the potential for a major incident involving multiple loss of life is always present in underground operations. Two primary causes of such catastrophes are cave-ins due to faulty engineering of the tunnels and explosion and fire due to the accumulation of methane and/or flammable levels of airborne coal dust.

Methane

Methane is highly explosive in concentrations of 5 to 15% and has been the cause of numerous mining disasters. It is best controlled by providing adequate air flow to dilute the gas to a level that is below its explosive range and to exhaust it quickly from the workings. Methane levels must be continuously monitored and rules established to close down operations when its concentration reaches 1 to 1.5% and to evacuate the mine promptly if it reaches levels of 2 to 2.5%.

Coal dust

In addition to causing black lung disease (anthracosis) if inhaled by miners, coal dust is explosive when fine dust is mixed with air and ignited. Airborne coal dust can be controlled by water sprays and exhaust ventilation. It can be collected by filtering recirculating air or it can be neutralized by the addition of stone dust in sufficient quantities to render the coal dust/air mixture inert.

Techniques in Underground Mining

There are underground mines all over the world presenting a kaleidoscope of methods and equipment. There are approximately 650 underground mines, each with an annual output that exceeds 150,000 tonnes, which account for 90% of the ore output of the western world. In addition, it is estimated that there are 6,000 smaller mines each producing less than 150,000 tonnes. Each mine is unique with workplace, installations and underground workings dictated by the kinds of minerals being sought and the location and geological formations, as well as by such economic considerations as the market for the particular mineral and the availability of funds for investment. Some mines have been in continuous operation for more than a century while others are just starting up.

Mines are dangerous places where most of the jobs involve arduous labour. The hazards faced by the workers range from such catastrophes as cave-ins, explosions and fire to accidents, dust exposure, noise, heat and more. Protecting the health and safety of the workers is a major consideration in properly conducted mining operations and, in most countries, is required by laws and regulations.

The Underground Mine

The underground mine is a factory located in the bedrock inside the earth in which miners work to recover minerals hidden in the rock mass. They drill, charge and blast to access and recover the ore, i.e., rock containing a mix of minerals of which at least one can be processed into a product that can be sold at a profit. The ore is taken to the surface to be refined into a high-grade concentrate.

Working inside the rock mass deep below the surface requires special infrastructures: a network of shafts, tunnels and chambers connecting with the surface and allowing movement of workers, machines and rock within the mine. The shaft is the access to underground where lateral drifts connect the shaft station with production stopes. The internal ramp is an inclined drift which links underground levels at different elevations (i.e., depths). All underground openings need services such as exhaust ventilation and fresh air, electric power, water and compressed air, drains and pumps to collect seeping ground water, and a communication system.

Hoisting plant and systems

The headframe is a tall building which identifies the mine on the surface. It stands directly above the shaft, the mine’s main artery through which the miners enter and leave their workplace and through which supplies and equipment are lowered and ore and waste materials are raised to the surface. Shaft and hoist installations vary depending on the need for capacity, depth and so on. Each mine must have at least two shafts to provide an alternate route for escape in case of an emergency.

Hoisting and shaft travelling are regulated by stringent rules. Hoisting equipment (e.g., winder, brakes and rope) is designed with ample margins of safety and is checked at regular intervals. The shaft interior is regularly inspected by people standing on top of the cage, and stop buttons at all stations trigger the emergency brake.

The gates in front of the shaft barricade the openings when the cage is not at the station. When the cage arrives and comes to a full stop, a signal clears the gate for opening. After miners have entered the cage and closed the gate, another signal clears the cage for moving up or down the shaft. Practice varies: the signal commands may be given by a cage tender or, following the instructions posted at each shaft station, the miners may signal shaft destinations for themselves. Miners are generally quite aware of the potential hazards in shaft riding and hoisting and accidents are rare.

Diamond drilling

A mineral deposit inside the rock must be mapped before the start of mining. It is necessary to know where the orebody is located and define its width, length and depth to achieve a three-dimensional vision of the deposit.

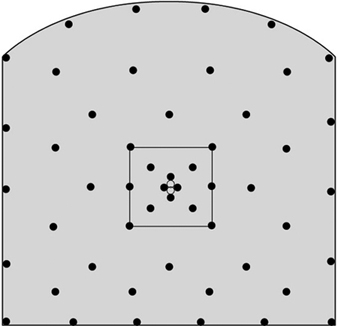

Diamond drilling is used to explore a rock mass. Drilling can be done from the surface or from the drift in the underground mine. A drill bit studded with small diamonds cuts a cylindrical core that is captured in the string of tubes that follows the bit. The core is retrieved and analysed to find out what is in the rock. Core samples are inspected and the mineralized portions are split and analysed for metal content. Extensive drilling programmes are required to locate the mineral deposits; holes are drilled at both horizontal and vertical intervals to identify the dimensions of the orebody (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Drill pattern, Garpenberg Mine, a lead-zinc mine, Sweden

Mine development

Mine development involves the excavations needed to establish the infrastructure necessary for stope production and to prepare for the future continuity of operations. Routine elements, all produced by the drill-blast-excavation technique, include horizontal drifts, inclined ramps and vertical or inclined raises.

Shaft sinking

Shaft sinking involves rock excavation advancing downwards and is usually assigned to contractors rather than being done by mine’s personnel. It requires experienced workers and special equipment, such as a shaft-sinking headframe, a special hoist with a large bucket hanging in the rope and a cactus-grab shaft mucking device.

The shaft-sinking crew is exposed to a variety of hazards. They work at the bottom of a deep, vertical excavation. People, material and blasted rock must all share the large bucket. People at the shaft bottom have no place to hide from falling objects. Clearly, shaft sinking is not a job for the inexperienced.

Drifting and ramping

A drift is a horizontal access tunnel used for transport of rock and ore. Drift excavation is a routine activity in the development of the mine. In mechanized mines, two-boom, electro-hydraulic drill jumbos are used for face drilling. Typical drift profiles are 16.0 m2 in section and the face is drilled to a depth of 4.0 m. The holes are charged pneumatically with an explosive, usually bulk ammonium nitrate fuel oil (ANFO), from a special charging truck. Short-delay non-electric (Nonel) detonators are used.

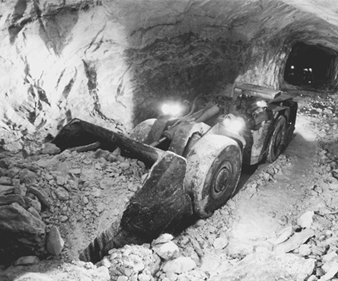

Mucking is done with (load-haul-dump) LHD vehicles (see figure 2) with a bucket capacity of about 3.0 m3. Muck is hauled directly to the ore pass system and transferred to truck for longer hauls. Ramps are passageways connecting one or more levels at grades ranging from 1:7 to 1:10 (a very steep grade compared to normal roads) that provide adequate traction for heavy, self-propelled equipment. The ramps are often driven in an upward or downward spiral, similar to a spiral staircase. Ramp excavation is a routine in the mine’s development schedule and uses the same equipment as drifting.

Figure 2. LHD loader

Atlas Copco

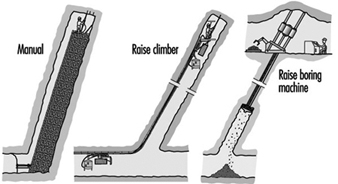

Raising

A raise is a vertical or steeply-inclined opening that connects different levels in the mine. It may serve as a ladderway access to stopes, as an ore pass or as an airway in the mine’s ventilation system. Raising is a difficult and dangerous, but necessary job. Raising methods vary from simple manual drill and blast to mechanical rock excavation with raise boring machines (RBMs) (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Raising methods

Manual raising

Manual raising is difficult, dangerous and physically demanding work that challenges the miner’s agility, strength and endurance. It is a job to be assigned only to experienced miners in good physical condition. As a rule the raise section is divided into two compartments by a timbered wall. One is kept open for the ladder used for climbing to the face, air pipes, etc. The other fills with rock from blasting which the miner uses as a platform when drilling the round. The timber parting is extended after each round. The work involves ladder climbing, timbering, rock drilling and blasting, all done in a cramped, poorly ventilated space. It is all performed by a single miner, as there is no room for a helper. Mines search for alternatives to the hazardous and laborious manual raising methods.

The raise climber

The raise climber is a vehicle that obviates ladder climbing and much of the difficulty of the manual method. This vehicle climbs the raise on a guide rail bolted to the rock and provides a robust working platform when the miner is drilling the round above. Very high raises can be excavated with the raise climber with safety much improved over the manual method. Raise excavation, however, remains a very hazardous job.

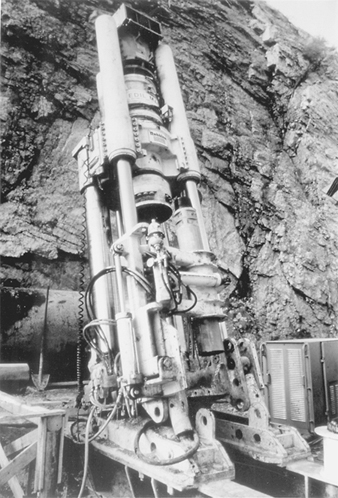

The raise boring machine

The RBM is a powerful machine that breaks the rock mechanically (see figure 4). It is erected on top of the planned raise and a pilot hole about 300 mm in diameter is drilled to break through at a lower level target. The pilot drill is replaced by a reamer head with the diameter of the intended raise and the RBM is put in reverse, rotating and pulling the reamer head upward to create a full-size circular raise.

Figure 4. Raise boring machine

Atlas Copco

Ground control

Ground control is an important concept for people working inside a rock mass. It is particularly important in mechanized mines using rubber-tyred equipment where the drift openings are 25.0 m2 in section, in contrast to the mines with rail drifts where they are usually only 10.0 m2. The roof at 5.0 m is too high for a miner to use a scaling bar to check for potential rock falls.

Different measures are used to secure the roof in underground openings. In smooth blasting, contour holes are drilled closely together and charged with a low-strength explosive. The blast produces a smooth contour without fracturing the outside rock.

Nevertheless, since there are often cracks in the rock mass which do not show on the surface, rock falls are an ever-present hazard. The risk is reduced by rock bolting, i.e., insertion of steel rods in bore holes and fastening them. The rock bolt holds the rock mass together, prevents cracks from spreading, helps to stabilize the rock mass and makes the underground environment safer.

Methods for Underground Mining

The choice of mining method is influenced by the shape and size of the ore deposit, the value of the contained minerals, the composition, stability and strength of the rock mass and the demands for production output and safe working conditions (which sometimes are in conflict). While mining methods have been evolving since antiquity, this article focuses on those used in semi- to fully-mechanized mines during the late twentieth century. Each mine is unique, but they all share the goals of a safe workplace and a profitable business operation.

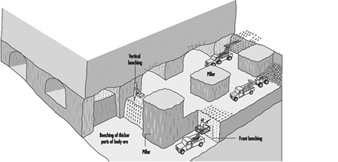

Flat room-and-pillar mining

Room-and-pillar mining is applicable to tabular mineralization with horizontal to moderate dip at an angle not exceeding 20° (see figure 5). The deposits are often of sedimentary origin and the rock is often in both hanging wall and mineralization in competent (a relative concept here as miners have the option to install rock bolts to reinforce the roof where its stability is in doubt). Room-and-pillar is one of the principal underground coal-mining methods.

Figure 5. Room-and-pillar mining of a flat orebody

Room-and-pillar extracts an orebody by horizontal drilling advancing along a multi-faced front, forming empty rooms behind the producing front. Pillars, sections of rock, are left between the rooms to keep the roof from caving. The usual result is a regular pattern of rooms and pillars, their relative size representing a compromise between maintaining the stability of the rock mass and extracting as much of the ore as possible. This involves careful analysis of the strength of the pillars, the roof strata span capacity and other factors. Rock bolts are commonly used to increase the strength of the rock in the pillars. The mined-out stopes serve as roadways for trucks transporting the ore to the mine’s storage bin.

The room-and-pillar stope face is drilled and blasted as in drifting. The stope width and height correspond to the size of the drift, which can be quite large. Large productive drill jumbos are used in normal height mines; compact rigs are used where the ore is less than 3.0 m thick. The thick orebody is mined in steps starting from the top so that the roof can be secured at a height convenient for the miners. The section below is recovered in horizontal slices, by drilling flat holes and blasting against the space above. The ore is loaded onto trucks at the face. Normally, regular front-end loaders and dump trucks are used. For the low-height mine, special mine trucks and LHD vehicles are available.

Room-and-pillar is an efficient mining method. Safety depends on the height of the open rooms and ground control standards. The main risks are accidents caused by falling rock and moving equipment.

Inclined room-and-pillar mining

Inclined room-and-pillar applies to tabular mineralization with an angle or dip from 15° and 30° to the horizontal. This is too steep an angle for rubber-tyred vehicles to climb and too flat for a gravity assist rock flow.

The traditional approach to the inclined orebody relies on manual labour. The miners drill blast holes in the stopes with hand-held rock drills. The stope is cleaned with slusher scrapers.

The inclined stope is a difficult place to work. The miners have to climb the steep piles of blasted rock carrying with them their rock drills and the drag slusher pulley and steel wires. In addition to rock falls and accidents, there are the hazards of noise, dust, inadequate ventilation and heat.

Where the inclined ore deposits are adaptable to mechanization, “step-room mining” is used. This is based on converting the “difficult dip” footwall into a “staircase” with steps at an angle convenient for trackless machines. The steps are produced by a diamond pattern of stopes and haulage-ways at the selected angle across the orebody.

Ore extraction starts with horizontal stope drives, branching out from a combined access-haulage drift. The initial stope is horizontal and follows the hanging wall. The next stope starts a short distance further down and follows the same route. This procedure is repeated moving downward to create a series of steps to extract the orebody.

Sections of the mineralization are left to support the hanging wall. This is done by mining two or three adjacent stope drives to the full length and then starting the next stope drive one step down, leaving an elongated pillar between them. Sections of this pillar can later be recovered as cut-outs that are drilled and blasted from the stope below.

Modern trackless equipment adapts well to step-room mining. The stoping can be fully mechanized, using standard mobile equipment. The blasted ore is gathered in the stopes by the LHD vehicles and transferred to mine truck for transport to the shaft/ore pass. If the stope is not high enough for truck loading, the trucks can be filled in special loading bays excavated in the haulage drive.

Shrinkage stoping

Shrinkage stoping may be termed a “classic” mining method, having been perhaps the most popular mining method for most of the past century. It has largely been replaced by mechanized methods but is still used in many small mines around the world. It is applicable to mineral deposits with regular boundaries and steep dip hosted in a competent rock mass. Also, the blasted ore must not be affected by storage in the slopes (e.g., sulphide ores have a tendency to oxidize and decompose when exposed to air).

Its most prominent feature is the use of gravity flow for ore handling: ore from stopes drops directly into rail cars via chutes obviating manual loading, traditionally the most common and least liked job in mining. Until the appearance of the pneumatic rocker shovel in the 1950s, there was no machine suitable for loading rock in underground mines.

Shrinkage stoping extracts the ore in horizontal slices, starting at the stope bottoms and advancing upwards. Most of the blasted rock remains in the stope providing a working platform for the miner drilling holes in the roof and serving to keep the stope walls stable. As blasting increases the volume of the rock by about 60%, some 40% of the ore is drawn at the bottom during stoping in order to maintain a work space between the top of the muckpile and the roof. The remaining ore is drawn after blasting has reached the upper limit of the stope.

The necessity of working from the top of the muckpile and the raise-ladder access prevents the use of mechanized equipment in the stope. Only equipment light enough for the miner to handle alone may be used. The air-leg and rock drill, with a combined weight of 45 kg, is the usual tool for drilling the shrinkage stope. Standing on top of the muckpile, the miner picks up the drill/feed, anchors the leg, braces the rock drill/drill steel against the roof and starts drilling; it is not easy work.

Cut-and-fill mining

Cut-and-fill mining is suitable for a steeply dipping mineral deposit contained in a rock mass with good to moderate stability. It removes the ore in horizontal slices starting from a bottom cut and advances upwards, allowing the stope boundaries to be adjusted to follow irregular mineralization. This permits high-grade sections to be mined selectively, leaving low-grade ore in place.

After the stope is mucked clean, the mined out space is backfilled to form a working platform when the next slice is mined and to add stability to the stope walls.

Development for cut-and-fill mining in a trackless environment includes a footwall haulage drive along the orebody at the main level, undercut of the stope provided with drains for the hydraulic backfill, a spiral ramp excavated in the footwall with access turn-outs to the stopes and a raise from the stope to the level above for ventilation and fill transport.

Overhand stoping is used with cut-and-fill, with both dry rock and hydraulic sand as backfill material. Overhand means that the ore is drilled from below by blasting a slice 3.0 m to 4.0 m thick. This allows the complete stope area to be drilled and the blasting of the full stope without interruptions. The “uppers” holes are drilled with simple wagon drills.

Up-hole drilling and blasting leaves a rough rock surface for the roof; after mucking out, its height will be about 7.0 m. Before miners are allowed to enter the area, the roof must be secured by trimming the roof contours with smooth-blasting and subsequent scaling of the loose rock. This is done by miners using hand-held rock drills working from the muckpile.

In front stoping, trackless equipment is used for ore production. Sand tailings are used for backfill and distributed in the underground stopes via plastic pipes. The stopes are filled almost completely, creating a surface sufficiently hard to be traversed by rubber-tyred equipment. The stope production is completely mechanized with drifting jumbos and LHD vehicles. The stope face is a 5.0 m vertical wall across the stope with a 0.5 m open slot beneath it. Five-meter-long horizontal holes are drilled in the face and ore is blasted against the open bottom slot.

The tonnage produced by a single blast depends on the face area and does not compare to that yielded by the overhand stope blast. However, the output of trackless equipment is vastly superior to the manual method, while roof control can be accomplished by the drill jumbo which drills smooth-blast holes together with the stope blast. Fitted with an oversize bucket and large tyres, the LHD vehicle, a versatile tool for mucking and transport, travels easily on the fill surface. In a double face stope, the drill jumbo engages it on one side while the LHD handles the muckpile at the other end, providing efficient use of the equipment and enhancing the production output.

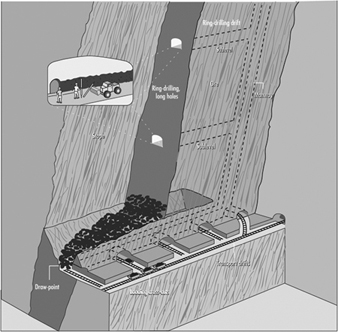

Sublevel stoping removes ore in open stopes. Backfilling of stopes with consolidated fill after the mining allows the miners to return at a later time to recover the pillars between the stopes, enabling a very high recovery rate of the mineral deposit.

Development for sublevel stoping is extensive and complex. The orebody is divided into sections with a vertical height of about 100 m in which sublevels are prepared and connected via an inclined ramp. The orebody sections are further divided laterally in alternating stopes and pillars and a mail haulage drive is created in the footwall, at the bottom, with cut-outs for drawpoint loading.

When mined out, the sublevel stope will be a rectangular opening across the orebody. The bottom of the stope is V-shaped to funnel the blasted material into the draw-points. Drilling drifts for the long-hole rig are prepared on the upper sublevels (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Sublevel stoping using ring drilling & cross-cut loading

Blasting requires space for the rock to expand in volume. This requires that a slot a few metres wide be prepared before the start of long-hole blasting. This is accomplished by enlarging a raise from the bottom to the top of the stope to a full slot.

After opening the slot, the long-hole rig (see figure 7) begins production drilling in sublevel drifts following precisely a detailed plan designed by blasting experts which specifies all the blast holes, the collaring position, depth and direction of the holes. The drill rig continues drilling until all the rings on one level are completed. It is then transferred to the next sublevel to continue drilling. Meanwhile the holes are charged and a blast pattern which covers a large area within the stope breaks up a large volume of ore in one blast. The blasted ore drops to the stope bottom to be recovered by the LHD vehicles mucking in the draw-point beneath the stope. Normally, the long-hole drilling stays ahead of the charging and blasting providing a reserve of ready-to-blast ore, thus making for an efficient production schedule.

Figure 7. Long-hole drill rig

Atlas Copco

Sublevel stoping is a productive mining method. Efficiency is enhanced by the ability to use fully mechanized productive rigs for the long-hole drilling plus the fact that the rig can be used continuously. It is also relatively safe because doing the drilling inside sublevel drifts and mucking through draw-points eliminates exposure to potential rock falls.

Vertical crater retreat mining

Like sublevel stoping and shrinkage stoping, vertical crater retreat (VCR) mining is applicable to mineralization in steeply dipping strata. However, it uses a different blasting technique breaking the rock with heavy, concentrated charges placed in holes (“craters”) with very large diameter (about 165 mm) about 3 m away from a free rock surface. Blasting breaks a cone-shaped opening in the rock mass around the hole and allows the blasted material to remain in the stope during the production phase so that the rock fill can assist in supporting the stope walls. The need for rock stability is less than in sublevel stoping.

The development for VCR mining is similar to that for sublevel stoping except for requiring both over-cut and under-cut excavations. The over-cut is needed in the first stage to accommodate the rig drilling the large-diameter blast holes and for access while charging the holes and blasting. The under-cut excavation provided the free surface necessary for VCR blasting. It may also provide access for a LHD vehicle (operated by remote control with the operator remaining outside the stope) to recover the blasted ore from the draw-points beneath the stope.

The usual VCR blast uses holes in a 4.0 × 4.0 m pattern directed vertically or steeply inclined with charges carefully placed at calculated distances to free the surface beneath. The charges cooperate to break off a horizontal ore slice about 3.0 m thick. The blasted rock falls into the stope underneath. By controlling the rate of mucking out, the stope remains partly filled so that the rock fill assists in stabilizing the stope walls during the production phase. The last blast breaks the over-cut into the stope, after which the stope is mucked clean and prepared for back filling.

VCR mines often uses a system of primary and secondary stopes to the orebody. Primary stopes are mined in the first stage, then backfilled with cemented fill. The stope is left for the fill to consolidate. Miners then return and recover the ore in the pillars between the primary stopes, the secondary stopes. This system, in combination with the cemented backfill, results in close to a 100% recovery of the ore reserves.

Sublevel caving

Sublevel caving is applicable to mineral deposits with steep to moderate dip and large extension at depth. The ore must fracture into manageable block with blasting. The hanging wall will cave following the ore extraction and the ground on the surface above the orebody will subside. (It must be barricaded to prevent any individuals from entering the area.)

Sublevel caving is based on gravity flow inside a broken-up rock mass containing both ore and rock. The rock mass is first fractured by drilling and blasting and then mucked out through drift headings underneath the rock mass cave. It qualifies as a safe mining method because the miners always work inside drift-size openings.

Sublevel caving depends on sublevels with regular patterns of drifts prepared inside the orebody at rather close vertical spacing (from 10.0 m to 20 0 m). The drift layout is the same on each sublevel (i.e., parallel drives across the orebody from the footwall transport drive to the hanging wall) but the patterns on each sublevel are slightly off-set so that the drifts on a lower level are located between the drifts on the sublevel above it. A cross section will show a diamond pattern with drifts in regular vertical and horizontal spacing. Thus, development for sublevel caving is extensive. Drift excavation, however, is a straightforward task which can readily be mechanized. Working on multiple drift headings on several sublevels favours high utilization of the equipment.

When the development of the sublevel is completed, the long-hole drill rig moves in to drill a blast holes in a fan-spread pattern in the rock above. When all of the blast holes are ready, the long-hole drill rig is moved to the sublevel below.

The long-hole blast fractures the rock mass above the sublevel drift, initiating a cave that starts at the hanging wall contact and retreats toward the footwall following a straight front across the orebody on the sublevel. A vertical section would show a staircase where each upper sublevel is one step ahead of the sublevel below.

The blast fills the sublevel front with a mix of ore and waste. When the LHD vehicle arrives, the cave contains 100% ore. As loading continues, the proportion of waste rock will gradually increase until the operator decides that the waste dilution is too high and stops loading. As the loader moves to the next drift to continue mucking, the blaster enters to prepare the next ring of holes for blasting.

Mucking out on sublevels is an ideal application for the LHD vehicle. Available in different sizes to meet particular situations, it fills the bucket, travels some 200 m, empties the bucket into the ore pass and returns for another load.

Sublevel caving features a schematic layout with repetitive work procedures (development drifting, long-hole drilling, charging and blasting, loading and transport) that are carried out independently. This allows the procedures to move continuously from one sublevel to another, allowing for the most efficient use of work crews and equipment. In effect the mine is analogous to a departmentalized factory. Sublevel mining, however, being less selective than other methods, does not yield particularly efficient extraction rates. The cave includes some 20 to 40% of waste with a loss of ore that ranges from 15 to 25%.

Block-caving

Block-caving is a large-scale method applicable to mineralization on the order of 100 million tonnes in all directions contained in rock masses amenable to caving (i.e., with internal stresses which, after removal of the supporting elements in the rock mass, assist the fracturing of the mined block). An annual output ranging from 10 to 30 million tonnes is the anticipated yield. These requirements limit block-caving to a few specific mineral deposits. Worldwide, there are block-caving mines exploiting deposits containing copper, iron, molybdenum and diamonds.

Block refers to the mining layout. The orebody is divided into large sections, blocks, each containing a tonnage sufficient for many years of production. The caving is induced by removing the supporting strength of the rock mass directly underneath the block by means of an undercut, a 15 m high section of rock fractured by long-hole drilling and blasting. Stresses created by natural tectonic forces of considerable magnitude, similar to those causing continental movements, create cracks in the rock mass, breaking the blocks, hopefully to pass draw-point openings in the mine. Nature, though, often needs the assistance of miners to handle oversize boulders.

Preparation for block-caving requires long-range planning and extensive initial development involving a complex system of excavations beneath the block. These vary with the site; they generally include undercut, drawbells, grizzlies for control of oversize rock and ore passes that funnel the ore into train loading.

Drawbells are conical openings excavated underneath the undercut which gather ore from a large area and funnel it into the drawpoint at the production level below. Here the ore is recovered in LHD vehicles and transferred to ore passes. Boulders too large for the bucket are blasted in draw-points, while smaller ones are dealt with on the grizzly. Grizzlies, sets of parallel bars for screening coarse material, are commonly used in block-caving mines although, increasingly, hydraulic breakers are being preferred.

Openings in a block-caving mine are subject to high rock pressure. Drifts and other openings, therefore, are excavated with the smallest possible section. Nevertheless, extensive rock bolting and concrete lining is required to keep the openings intact.

Properly applied, block-caving is a low-cost, productive mass mining method. However, the amenability of a rock mass to caving is not always predictable. Also, the comprehensive development that is required results in a long lead-time before the mine starts producing: the delay in earnings can have a negative influence on the financial projections used to justify the investment.

Longwall mining

Longwall mining is applicable to bedded deposits of uniform shape, limited thickness and large horizontal extension (e.g., a coal seam, a potash layer or the reef, the bed of quartz pebbles exploited by gold mines in South Africa). It is one of the main methods for mining coal. It recovers the mineral in slices along a straight line that are repeated to recover materials over a larger area. The space closest to the face in kept open while the hanging wall is allowed to collapse at a safe distance behind the miners and their equipment.

Preparation for longwall mining involves the network of drifts required for access to the mining area and transport of the mined product to the shaft. Since the mineralization is in the form of a sheet that extends over a wide area, the drifts can usually be arranged in a schematic network pattern. The haulage drifts are prepared in the seam itself. The distance between two adjacent haulage drifts determines the length of the longwall face.

Backfilling

Backfilling of mine stopes prevents rock from collapsing. It preserves the inherent stability of the rock mass which promotes safety and allows more complete extraction of the desired ore. Backfilling is traditionally used with cut-and-fill but it is also common with sublevel stoping and VCR mining.

Traditionally, miners have dumped waste rock from development in empty stopes instead of hauling it to the surface. For example, in cut-and-fill, waste rock is distributed over the empty stope by scrapers or bulldozers.

Hydraulic backfilling uses tailings from the mine’s dressing plant which are distributed underground through bore holes and plastic tubing. The tailings are first de-slimed, only the coarse fraction being used for filling. The fill is a mix of sand and water, about 65% of which is solid matter. By mixing cement into the last pour, the fill’s surface will harden into a smooth roadbed for rubber-tyred equipment.

Backfilling is also used with sublevel stoping and VCR mining, with crushed rock introduced as a complement to sand fill. The crushed and screened rock, produced in a nearby quarry, is delivered underground through special backfill raises where it is loaded on trucks and delivered to the stopes where it is dumped into special fill raises. Primary stopes are backfilled with cemented rock fill produced by spraying a cement-fly ash slurry on the rockfill before it is distributed to the stopes. The cemented rockfill hardens into a solid mass forming an artificial pillar for mining the secondary stope. The cement slurry is generally not required when secondary stopes are backfilled, except for the last pours to establish a firm mucking floor.

Equipment for Underground Mining

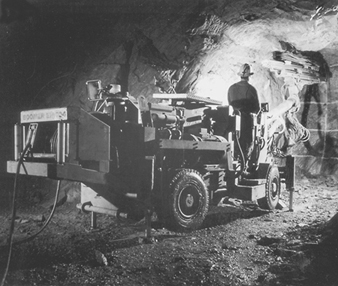

Underground mining is becoming increasingly mechanized wherever circumstances permit. The rubber-tyred, diesel-powered, four-wheel traction, articulated steer carrier is common to all mobile underground machines (see figure 8).

Figure 8. Small-size face rig

Atlas Copco

Face drill jumbo for development drilling

This is an indispensable workhorse in mines that is used for all rock excavation work. It carries one or two booms with hydraulic rock drills. With one worker at the control panel, it will complete a pattern of 60 blast holes 4.0 m deep in a few hours.

Long-hole production drill rig

This rig (see figure 7 drills blast holes in a radial spread around the drift which cover a large area of rock and break off large volumes of ore. It is used with sublevel stoping, sublevel caving, block-caving and VCR mining. With a powerful hydraulic rock drill and carousel storage for extension rods, the operator uses remote controls to perform rock drilling from a safe position.

Charging truck

The charging truck is a necessary complement to the drifting jumbo. The carrier mounts a hydraulic service platform, a pressurized ANFO explosive container and a charging hose that permit the operator to fill blast holes all over the face in a very short time. At the same time, Nonel detonators may be inserted for the correct timing of the individual blasts.

LHD vehicle

The versatile load-haul-dump vehicle (see figure 10) is used for a variety of services including ore production and materials handling. It is available in a choice of sizes allowing miners to select the model most appropriate for each task and each situation. Unlike the other diesel vehicles used in mines, the LHD vehicle engine is generally run continuously at full power for long periods of time generating large volumes of smoke and exhaust fumes. A ventilation system capable of diluting and exhausting these fumes is essential to compliance with acceptable breathing standards in the loading area.

Underground haulage

The ore recovered in stopes spread along an orebody is transported to an ore dump located close to the hoisting shaft. Special haulage levels are prepared for longer lateral transfer; they commonly feature rail track installations with trains for ore transport. Rail has proved to be an efficient transport system carrying larger volumes for longer distances with electric locomotives that do not contaminate the underground atmosphere like diesel-powered trucks used in trackless mines.

Ore handling

On its route from the stopes to the hoisting shaft, the ore passes several stations with a variety of materials-handling techniques.

The slusher uses a scraper bucket to draw ore from the stope to the ore pass. It is equipped with rotating drums, wires and pulleys, arranged to produce a back and forth scraper route. The slusher does not need preparation of the stope flooring and can draw ore from a rough muckpile.

The LHD vehicle, diesel powered and travelling on rubber tyres, takes the volume held in its bucket (sizes vary) from the muckpile to the ore pass.

The ore pass is a vertical or steeply inclined opening through which rock flows by gravity from upper to lower levels. Ore passes are sometimes arranged in a vertical sequence to collect ore from upper levels to a common delivery point on the haulage level.

The chute is the gate located at the bottom of the ore pass. Ore passes normally end in rock close to the haulage drift so that, when the chute is opened, the ore can flow to fill cars on the track beneath it.

Close to the shaft, the ore trains pass a dump station where the load may be dropped into a storage bin, A grizzly at the dump station stops oversized rocks from falling into the bin. These boulders are split by blasting or hydraulic hammers; a coarse crusher may be installed below the grizzly for further size control. Under the storage bin is a measure pocket which automatically verifies that the load’s volume and weight do not exceed the capacities of the skip and the hoist. When an empty skip, a container for vertical travel, arrives at the filling station, a chute opens in the bottom of the measure pocket filling the skip with a proper load. After the hoist lifts the loaded skip to the headframe on the surface, a chute opens to discharge the load into the surface storage bin. Skip hoisting can be automatically operated using closed-circuit television to monitor the process.

Underground Coal Mining

Underground coal production first began with access tunnels, or adits, being mined into seams from their surface outcrops. However, problems caused by inadequate means of transport to bring coal to the surface and by the increasing risk of igniting pockets of methane from candles and other open flame lights limited the depth to which early underground mines could be worked.

Increasing demand for coal during the Industrial Revolution gave the incentive for shaft sinking to access deeper coal reserves, and by the mid-twentieth century by far the greater proportion of world coal production came from underground operations. During the 1970s and 1980s there was widespread development of new surface coal mine capacity, particularly in countries such as the United States, South Africa, Australia and India. In the 1990s, however, renewed interest in underground mining resulted in new mines being developed (in Queensland, Australia, for instance) from the deepest points of former surface mines. In the mid-1990s, underground mining accounted for perhaps 45% of all the hard coal mined worldwide. The actual proportion varied widely, ranging from under 30% in Australia and India to around 95% in China. For economic reasons, lignite and brown coal are rarely mined underground.

An underground coal mine consists essentially of three components: a production area; coal transport to the foot of a shaft or decline; and either hoisting or conveying the coal to the surface. Production also includes the preparatory work that is needed in order to permit access to future production areas of a mine and, in consequence, represents the highest level of personal risk.

Mine Development

The simplest means of accessing a coal seam is to follow it in from its surface outcrop, a still widely practised technique in areas where the overlying topography is steep and the seams are relatively flat-lying. An example is the Appalachian coalfield of southern West Virginia in the United States. The actual mining method used in the seam is immaterial at this point; the important factor is that access can be gained cheaply and with minimal construction effort. Adits are also commonly used in areas of low-technology coal mining, where the coal produced during mining of the adit can be used to offset its development costs.

Other means of access include declines (or ramps) and vertical shafts. The choice usually depends on the depth of the coal seam being worked: the deeper the seam, the more expensive it is to develop a graded ramp along which vehicles or belt conveyors can operate.

Shaft sinking, in which a shaft is mined vertically downwards from the surface, is both costly and time-consuming and requires a longer lead-time between the commencement of construction and the first coal being mined. In cases where the seams are deep-lying, as in most European countries and in China, shafts often have to be sunk through water-bearing rocks overlying the coal seams. In this instance, specialist techniques, such as ground freezing or grouting, have to be used to prevent water from flowing into the shaft, which is then lined with steel rings or cast concrete to provide a long-term seal.