57. Audits, Inspections and Investigations

Chapter Editor: Jorma Saari

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Safety Audits and Management Audits

Johan Van de Kerckhove

Hazard Analysis: The Accident Causation Model

Jop Groeneweg

Hardware Hazards

Carsten D. Groenberg

Hazard Analysis: Organizational Factors

Urban Kjellén

Workplace Inspection and Regulatory Enforcement

Anthony Linehan

Analysis and Reporting: Accident Investigation

Michel Monteau

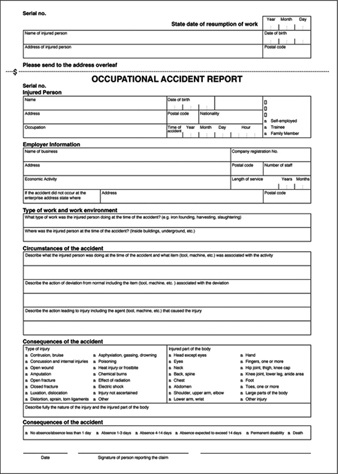

Reporting and Compiling Accident Statistics

Kirsten Jorgensen

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Strata in quality & safety policy

2. PAS safety audit elements

3. Assessment of behaviour-control methods

4. General failure types & definitions

5. Concepts of the accident phenomenon

6. Variables characterizing an accident

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Safety Audits and Management Audits

During the 1990s, the organizational factors in safety policy are becoming increasingly important. At the same time, the views of organizations regarding safety have dramatically changed. Safety experts, most of whom have a technical training background, are thus confronted with a dual task. On the one hand, they have to learn to understand the organizational aspects and take them into account in constructing safety programmes. On the other hand, it is important that they be aware of the fact that the view of organizations is moving further and further away from the machine concept and placing a clear emphasis on less tangible and measurable factors such as organizational culture, behaviour modification, responsibility-raising or commitment. The first part of this article briefly covers developments in opinions relating to organizations, management, quality and safety. The second part of the article defines the implications of these developments for audit systems. This is then very briefly placed in a tangible context using the example of an actual safety audit system based on the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001 standards.

New Opinions Concerning Organization and Safety

Changes in social-economic circumstances

The economic crisis that started to impact upon the Western world in 1973 has had a significant influence on thought and action in the field of management, quality and work safety. In the past, the accent in economic development was placed on expansion of the market, increasing exports and improving productivity. However, the emphasis gradually shifted to the reduction of losses and the improvement of quality. In order to retain and acquire customers, a more direct response was provided to their requirements and expectations. This resulted in a need for greater product differentiation, with the direct consequence of greater flexibility within organizations in order to always be able to respond to market fluctuations on a “just in time” basis. Emphasis was placed on the commitment and creativity of employees as the major competitive advantage in the economic competitive struggle. Besides increasing quality, limiting loss-making activities became an important means of improving operating results.

Safety experts enlisted in this strategy by developing and instituting “total loss control” programmes. Not only are the direct costs of accidents or the increased insurance premiums significant in these programmes, but so also are all direct or indirect unnecessary costs and losses. A study of how much production should be increased in real terms to compensate for these losses immediately reveals that reducing costs is today often more efficient and profitable than increasing production.

In this context of improved productivity, reference was recently made to the major benefits of reducing absenteeism due to sickness and stimulating employee motivation. Against the background of these developments, safety policy is increasingly and clearly taking on a new form with different accents. In the past, most corporate leaders considered work safety as merely a legal obligation, as a burden they would quickly delegate to technical specialists. Today, safety policy is more and more distinctly being viewed as a way of achieving the two aims of reducing losses and optimizing corporate policy. Safety policy is therefore increasingly evolving into a reliable barometer of the soundness of the corporation’s success with respect to these aims. In order to measure progress, increased attention is being devoted to management and safety audits.

Organizational Theory

It is not only economic circumstances that have given company heads new insights. New visions relating to management, organizational theory, total quality care and, in the same vein, safety care, are resulting in significant changes. An important turning point in views on the organization was elaborated in the renowned work published by Peters and Waterman (1982), In Search of Excellence. This work was already espousing the ideas which Pascale and Athos (1980) discovered in Japan and described in The Art of Japanese Management. This new development can be symbolized in a sense by McKinsey’s “7-S” Framework (in Peters and Waterman 1982). In addition to three traditional management aspects (Strategy, Structure and Systems), corporations now also emphasize three additional aspects ( Staff, Skills and Style). All six of these interact to provide the input to the 7th “S”, Superordinate goals (figure 1). With this approach, a very clear accent is placed on the human-oriented aspects of the organization.

Figuer 1.The values, mission and organizational culture of a corporation according to McKinsey’s 7-S Framework

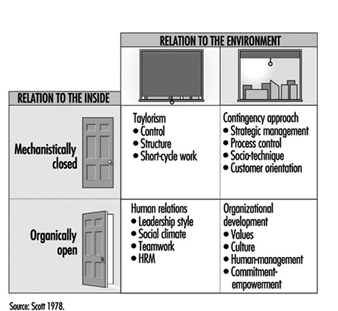

The fundamental shifts can best be demonstrated on the basis of the model presented by Scott (1978), which was also used by Peters and Waterman (1982). This model uses two approaches:

- The closed-system approaches deny the influence of developments from outside the organization. With the mechanistic closed approaches, the objectives of an organization are clearly defined and can be logically and rationally determined.

- Open-system approaches take outside influences fully into account, and the objectives are more the result of diverse processes, in which clearly irrational factors contribute to decision making. These organically open approaches more truly reflect the evolution of an organization, which is not determined mathematically or on the basis of deductive logic, but grows organically on the basis of real people and their interactions and values (figure 2).

Figure 2.Organizational Theories

Four fields are thus created in figure 2 . Two of these (Taylorism and contingency approach) are mechanically closed, and the other two (human relations and organizational development) are organically open. There has been enormous development in management theory, moving from the traditional rational and authoritarian machine model (Taylorism) to the human-oriented organic model of human resources management (HRM).

Organizational effectiveness and efficiency are being more clearly linked to optimal strategic management, a flat organizational structure and sound quality systems. Furthermore, attention is now given to superordinate goals and significant values that have a bonding effect within the organization, such as skills (on the basis of which the organization stands out from its competitors) and a staff that is motivated to maximum creativity and flexibility by placing the emphasis on commitment and empowerment. With these open approaches, a management audit cannot limit itself to a number of formal or structural characteristics of the organization. The audit must also include a search for methods to map out less tangible and measurable cultural aspects.

From product control to total quality management

In the 1950s, quality was limited to a post-factum end product control, total quality control (TQC). In the 1970s, partly stimulated by NATO and the automotive giant Ford, the accent shifted to the achievement of the goal of total quality assurance (TQA) during the production process. It was only during the 1980s that, stimulated by Japanese techniques, attention shifted towards the quality of the total management system and total quality management (TQM) was born. This fundamental change in the quality care system has taken place cumulatively in the sense that each foregoing stage was integrated into the next. It is also clear that while product control and safety inspection are facets more closely related to a Tayloristic organizational concept, quality assurance is more associated with a socio-technical system approach where the aim is not to betray the trust of the (external) customer. TQM, finally, relates to an HRM approach by the organization as it is no longer solely the improvement of the product that is involved, but continuous improvement of the organizational aspects in which explicit attention is also devoted to the employees.

In the total quality leadership (TQL) approach of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), the emphasis is very strongly placed on the equal impact of the organization on the customer, the employees and the overall society, with the environment as the key point of attention. These objectives can be realized by including concepts such as “leadership” and “people management”.

It is clear that there is also a very important difference in emphasis between quality assurance as described in the ISO standards and the TQL approach of the EFQM. ISO quality assurance is an extended and improved form of quality inspection, focusing not only on the products and internal customers, but also on the efficiency of the technical processes. The objective of the inspection is to investigate the conformity with the procedures set out in ISO. TQM, on the other hand, endeavours to meet the expectations of all internal and external customers as well as all processes within the organization, including the more soft and human-oriented ones. The involvement, the commitment and the creativity of the employees are clearly important aspects of TQM.

From Human Error to Integrated Safety

Safety policy has evolved in a similar manner to quality care. Attention has shifted from post-factum accident analysis, with emphasis on the prevention of injuries, to a more global approach. Safety is seen more in the context of “total loss control” - a policy aimed at the avoidance of losses through management of safety involving the interaction of people, processes, materials, equipment, installations and the environment. Safety therefore focuses on the management of the processes that could lead to losses. In the initial development period of safety policy the emphasis was placed on a human error approach. Consequently, employees were given a heavy responsibility for the prevention of industrial accidents. Following a Tayloristic philosophy, conditions and procedures were drawn up and a control system was established to maintain the prescribed standards of behaviour. This philosophy may filter through into modern safety policy via the ISO 9000 concepts resulting in the imposition of a sort of implicit and indirect feeling of guilt upon the employees, with all the adverse consequences this entails for the corporate culture - for instance, a tendency may develop that performance will be impeded rather than enhanced.

At a later stage in the evolution of safety policy, it was recognized that employees carry out their work in a particular environment with well-defined working resources. Industrial accidents were considered as a multicausal event in a human/machine/environment system in which the emphasis shifted in a technical-system approach. Here again we find the analogy with quality assurance, where the accent is placed on controlling technical processes through means such as statistical process control.

Only recently, and partly stimulated by the TQM philosophy, has the emphasis in safety policy systems shifted into a social-system approach, which is a logical step in the improvement of the prevention system. In order to optimize the human/machine/environment system it is not sufficient to ensure safe machines and tools by means of a well-developed prevention policy, but there is also the need for a preventive maintenance system and the assurance of security among all technical processes. Moreover, it is of crucial importance that employees be sufficiently trained, skilled and motivated with regard to health and safety objectives. In today’s society, the latter objective can no longer be achieved through the authoritarian Tayloristic approach, as positive feedback is much more stimulating than a repressive control system that often has only negative effects. Modern management entails an open, motivating corporate culture, in which there is a common commitment to achieving key corporate objectives in a participatory, team-based approach. In the safety-culture approach, safety is an integral part of the objectives of the organizations and therefore an essential part of everyone’s task, starting with top management and passing along the entire hierarchical line down to employees on the shop floor.

Integrated safety

The concept of integrated safety immediately presents a number of central factors in an integrated safety system, the most important of which can be summarized as follows:

A clearly visible commitment from the top management. This commitment is not only given on paper, but is translated right down to the shop floor in practical achievements.

Active involvement of the hierarchical line and the central support departments. Care for safety, health and welfare is not only an integral part of everyone’s task in the production process, but is also integrated into the personnel policy, into preventive maintenance, into the design stage and into working with third parties.

Full participation of the employees. Employees are full discussion partners with whom open and constructive communication is possible, with their contribution being given full weight. Indeed, participation is of crucial importance for carrying through corporate and safety policy in an efficient and motivating way.

A suitable profile for a safety expert. The safety expert is no longer the technician or jack of all trades, but is a qualified adviser to the top management, with particular attention being devoted to optimizing the policy processes and the safety system. He or she is therefore not someone who is only technically trained, but also a person who, as a good organizer, can deal with people in an inspiring manner and collaborate in a synergetic way with other prevention experts.

A pro-active safety culture. The key aspect of an integrated safety policy is a pro-active safety culture, which includes, among other things, the following:

- Safety, health and welfare are the key ingredients of an organization’s value system and of the objectives it seeks to attain.

- An atmosphere of openness prevails, based on mutual trust and respect.

- There is a high level of cooperation with a smooth flow of information and an appropriate level of coordination.

- A pro-active policy is implemented with a dynamic system of constant improvement perfectly matching the prevention concept.

- The promotion of safety, health and welfare is a key component of all decision-making, consultations and teamwork.

- When industrial accidents occur, suitable preventive measures are sought, not a scapegoat.

- Members of staff are encouraged to act on their own initiative so that they possess the greatest possible authority, knowledge and experience, enabling them to intervene in an appropriate manner in unexpected situations.

- Processes are set in motion with a view to promoting individual and collective training to the maximum extent possible.

- Discussions concerning challenging and attainable health, safety and welfare objectives are held on a regular basis.

Safety and Management Audits

General description

Safety audits are a form of risk analysis and evaluation in which a systematic investigation is carried out in order to determine the extent to which the conditions are present that provide for the development and implementation of an effective and efficient safety policy. Each audit therefore simultaneously envisions the objectives that must be realized and the best organizational circumstances to put these into practice.

Each audit system should, in principle, determine the following:

- What is management seeking to achieve, by what means and by what strategy?

- What are the necessary provisions in terms of resources, structures, processes, standards and procedures that are required to achieve the proposed objectives, and what has been provided? What minimum programme can be put forward?

- What are the operational and measurable criteria that must be met by the chosen items to allow the system to function optimally?

The information is then thoroughly analysed to examine to what extent the current situation and the degree of achievement meet the desired criteria, followed by a report with positive feedback that emphasizes the strong points, and corrective feedback that refers to aspects requiring further improvement.

Auditing and strategies for change

Each audit system explicitly or implicitly contains a vision both of an ideal organization’s design and conceptualization, and of the best way of implementing improvements.

Bennis, Benne and Chin (1985) distinguish three strategies for planned changes, each based on a different vision of people and of the means of influencing behaviour:

- Power-force strategies are based on the idea that the behaviour of employees can be changed by exercising sanctions.

- Rational-empirical strategies are based on the axiom that people make rational choices depending on maximizing their own benefits.

- Normative-re-educative strategies are based on the premise that people are irrational, emotional beings and in order to realize a real change, attention must also be devoted to their perception of values, culture, attitudes and social skills.

Which influencing strategy is most appropriate in a specific situation not only depends on the starting vision, but also on the actual situation and the existing organizational culture. In this respect it is very important to know which sort of behaviour to influence. The famous model devised by Danish risk specialist Rasmussen (1988) distinguishes among the following three sorts of behaviour:

- Routine actions (skill-based behaviour) automatically follow the associated signal. Such actions are carried out without one’s consciously devoting attention to them - for example, touch-typing or manually changing gears when driving.

- Actions in accordance with instructions (rule-based) require more conscious attention because no automatic response to the signal is present and a choice must be made between different possible instructions and rules. These are often actions which can be placed in an “ifthen” sequence, as in “If the meter rises to 50 then this valve must be closed”.

- Actions based on knowledge and insight (knowledge-based) are carried out after a conscious interpretation and evaluation of the different problem signals and the possible alternative solutions. These actions therefore presuppose a fairly high degree of knowledge of and insight into the process concerned, and the ability to interpret unusual signals.

Strata in behavioural and cultural change

Based on the above, most audit systems (including those based on the ISO series of standards) implicitly depart from power-force strategies or rational-empirical strategies, with their emphasis on routine or procedural behaviour. This means that insufficient attention is paid in these audit systems to “knowledge-based behaviour” that can be influenced mainly via normative–re-educative strategies. In the typology used by Schein (1989), attention is devoted only to the tangible and conscious surface phenomena of the organizational culture and not to the deeper invisible and subconscious strata that refer more to values and fundamental presuppositions.

Many audit systems limit themselves to the question of whether a particular provision or procedure is present. It is therefore implicitly assumed that the sheer existence of this provision or procedure is a sufficient guarantee for the good functioning of the system. Besides the existence of certain measures, there are always different other “strata” (or levels of probable response) that must be addressed in an audit system to provide sufficient information and guarantees for the optimum functioning of the system.

In more concrete terms, the following example concerns response to a fire emergency:

- A given provision, instruction or procedure is present (“sound the alarm and use the extinguisher”).

- A given instruction or procedure is also familiarly known to the parties concerned (workers know where alarms and extinguishers are located and how to activate and use them).

- The parties concerned also know as much as possible as to the “why and wherefore” of a particular measure (employees have been trained or educated in extinguisher use and typical types of fires).

- The employee is also motivated to apply needful measures (self preservation, save the job, etc.).

- There is sufficient motivation, competence and ability to act in unforeseen circumstances (employees know what to do in the event fire gets out of hand, requiring professional fire-fighting response).

- There are good human relations and an atmosphere of open communication (supervisors, managers and employees have discussed and agreed upon fire emergency response procedures).

- Spontaneous creative processes originate in a learning organiz-ation (changes in procedures are implemented following “lessons learned” in actual fire situations).

Table 1 lays out some strata in quality audio safety policy.

Table 1. Strata in quality and safety policy

|

Strategies |

Behaviour |

||

|

Skills |

Rules |

Knowledge |

|

|

Power-force |

Human error approach |

||

|

Rational-empirical |

Technical system approach |

||

|

Normative-re-educative |

Social system approach TQM |

Safety culture approach PAS EFQM |

|

The Pellenberg Audit System

The name Pellenberg Audit System (PAS) derives from the place where the designers gathered many times to develop the system (the Maurissens Château in Pellenberg, a building of the Catholic University of Leuven). PAS is the result of intense collaboration by an interdisciplinary team of experts with years of practical experience, both in the area of quality management and in the area of safety and environmental problems, in which a variety of approaches and experiences were brought together. The team also received support from the university science and research departments, and thus benefited from the most recent insights in the fields of management and organizational culture.

PAS encompasses an entire set of criteria that a superior company prevention system ought to meet (see table 2). These criteria are classified in accordance with the ISO standard system (quality assurance in design, development, production, installation and servicing). However, PAS is not a simple translation of the ISO system into safety, health and welfare. A new philosophy is developed, departing from the specific product that is achieved in safety policy: meaningful and safe jobs. The contract of the ISO system is replaced by the provisions of the law and by the evolving expectations that exist among the parties involved in the social field with regard to health, safety and welfare. The creation of safe and meaningful jobs is seen as an essential objective of each organization within the framework of its social responsibility. The enterprise is the supplier and the customers are the employees.

Table 2. PAS safety audit elements

|

PAS safety audit elements |

Correspondence with ISO 9001 |

|

|

1. |

Management responsibility |

|

|

1.1. |

Safety policy |

4.1.1. |

|

1.2. |

Organization |

|

|

1.2.1. |

Responsibility and authority |

4.1.2.1. |

|

1.2.2. |

Verification resources and personnel |

4.1.2.2. |

|

1.2.3. |

Health and safety service |

4.1.2.3. |

|

1.3. |

Safety management system review |

4.1.3. |

|

2. |

Safety management system |

4.2. |

|

3. |

Obligations |

4.3. |

|

4. |

Design control |

|

|

4.1. |

General |

4.4.1. |

|

4.2. |

Design and development planning |

4.4.2. |

|

4.3. |

Design input |

4.4.3. |

|

4.4. |

Design output |

4.4.4. |

|

4.5. |

Design verification |

4.4.5. |

|

4.6. |

Design changes |

4.4.6. |

|

5. |

Document control |

|

|

5.1. |

Document approval and issue |

4.5.1. |

|

5.2. |

Document changes/modifications |

4.5.2. |

|

6. |

Purchasing and contracting |

|

|

6.1. |

General |

4.6.1. |

|

6.2. |

Assessment of suppliers and contractors |

4.6.2. |

|

6.3. |

Purchasing data |

4.6.3. |

|

6.4. |

Third party’s products |

4.7. |

|

7. |

Identification |

4.8. |

|

8. |

Process control |

|

|

8.1. |

General |

4.9.1. |

|

8.2. |

Process safety control |

4.11. |

|

9. |

Inspection |

|

|

9.1. |

Receiving and pre-start-up inspection |

4.10.1. |

|

9.2. |

Periodic inspections |

4.10.2. |

|

9.3. |

Inspection records |

4.10.4. |

|

9.4. |

Inspection equipment |

4.11. |

|

9.5. |

Inspection status |

4.12. |

|

10. |

Accidents and incidents |

4.13. |

|

11. |

Corrective and preventive action |

4.13. |

|

12. |

Safety records |

4.16. |

|

13. |

Internal safety audits |

4.17. |

|

14. |

Training |

4.18. |

|

15. |

Maintenance |

4.19. |

|

16. |

Statistical techniques |

4.20. |

Several other systems are integrated in the PAS system:

- At a strategic level, the insights and requirements of ISO are of particular importance. As far as possible, these are comple-mented by the management vision as this was originally devel-oped by the European Foundation for Quality Management.

- At a tactical level, the systematics of the “Management’s Oversight and Risk Tree” encourages people to seek out what are the necessary and sufficient conditions in order to achieve the desired safety result.

- At an operational level a multitude of sources could be drawn upon, including existing legislation, regulations and other criteria such as the International Safety Rating System (ISRS), in which the emphasis is placed on certain concrete conditions that should guarantee the safety result.

The PAS constantly refers to the broader corporate policy within which the safety policy is embedded. After all, an optimum safety policy is at the same time a product and a producer of a pro-active company policy. Assuming that a safe company is at the same time an effective and efficient organization and vice versa, special attention is therefore devoted to the integration of safety policy in the overall policy. Essential ingredients of a future-oriented corporate policy include a strong corporate culture, a far-reaching commitment, the participation of the employees, a special emphasis on the quality of the work, and a dynamic system of continual improvement. Although these insights also partly form the background of the PAS, they are not always very easy to reconcile with the more formal and procedural approach of the ISO philosophy.

Formal procedures and directly identifiable results are indisputably important in safety policy. However, it is not enough to base the safety system on this approach alone. The future results of a safety policy are dependent on the present policy, on the systematic efforts, on the constant search for improvements, and particularly on the fundamental optimizing of processes that ensure durable results. This vision is incorporated in the PAS system, with strong emphasis among other things on a systematic improvement of the safety culture.

One of the main advantages of the PAS is the opportunity for synergy. By departing from the systematics of ISO, the diverse lines of approach become immediately recognizable for all those concerned with total quality management. There are clearly several opportunities for synergy between these various policy areas because in all these fields the improvement of the management processes is the key aspect. A careful purchasing policy, a sound system of preventive maintenance, good housekeeping, participatory management and the stimulation of an enterprising approach by employees are of paramount importance for all these policy areas.

The various care systems are organized in an analogous manner, based on principles such as the commitment of top management, the involvement of the hierarchical line, the active participation of employees, and a valorized contribution from the specific experts. The different systems also contain analogous policy instruments such as the policy statement, annual action plans, measuring and control systems, internal and external audits and so on. The PAS system therefore clearly invites the pursuance of an effective, cost-saving, synergetic cooperation between all these care systems.

The PAS does not offer the easiest road to achievement in the short term. Few company managers allow themselves to be seduced by a system that promises great benefits in the short term with little effort. Every sound policy requires an in-depth approach, with strong foundations being laid for future policy. More important than results in the short term is the guarantee that a system is being built up that will generate sustainable results in the future, not only in the field of safety, but also at the level of a generally effective and efficient corporate policy. In this respect working towards health, safety and welfare also means working towards safe and meaningful jobs, motivated employees, satisfied customers and an optimum operating result. All this takes place in a dynamic, pro-active atmosphere.

Summary

Continual improvement is an essential precondition for each safety audit system that seeks to reap lasting success in today’s rapidly evolving society. The best guarantee for a dynamic system of continual improvement and constant flexibility is the full commitment of competent employees who grow with the overall organization because their efforts are systematically valorized and because they are given the opportunities to develop and regularly update their skills. Within the safety audit process, the best guarantee of lasting results is the development of a learning organization in which both the employees and the organization continue to learn and evolve.

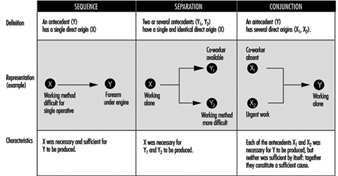

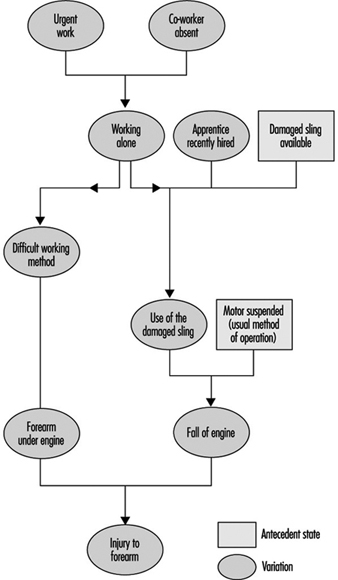

Hazard Analysis: The Accident Causation Model

This article examines the role of human factors in the accident causation process and reviews the various preventive measures (and their effectiveness) by which human error may be controlled, and their application to the accident causation model. Human error is an important contributing cause in at least 90 of all industrial accidents. While purely technical errors and uncontrollable physical circumstances may also contribute to accident causation, human error is the paramount source of failure. The increased sophistication and reliability of machinery means that the proportion of causes of accidents attributed to human error increases as the absolute number of accidents decreases. Human error is also the cause of many of those incidents that, although not resulting in injury or death, nevertheless result in considerable economic damage to a company. As such, it represents a major target for prevention, and it will become increasingly important. For effective safety management systems and risk identification programmes it is important to be able to identify the human component effectively through the use of general failure type analysis.

The Nature of Human Error

Human error can be viewed as the failure to reach a goal in the way that was planned, either from a local or wider perspective, due to unintentional or intentional behaviour. Those planned actions may fail to achieve the desired outcomes for the following four reasons:

1. Unintentional behaviour:

- The actions did not go as planned (slips).

- The action was not executed (lapses).

2. Intentional behaviour:

- The plan itself was inadequate (mistakes).

- There were deviations from the original plan (violations).

Deviations can be divided in three classes: skill-, rule- and knowledge-based errors.

- At the skill-based level, behaviour is guided by pre-programmed action schemes. The tasks are routine and continuous, and feedback is usually lacking.

- At the rule-based level, behaviour is guided by general rules. They are simple and can be applied many times in specific situations. The tasks consist of relatively frequent action sequences that start after a choice is made among rules or procedures. The user has a choice: the rules are not automatically activated, but are actively chosen.

- Knowledge-based behaviour is shown in completely new situations where no rules are available and where creative and analytical thinking is required.

In some situations, the term human limitation would be more appropriate than human error. There also are limits to the ability to foresee the future behaviour of complex systems (Gleick 1987; Casti 1990).

Reason and Embrey’s model, the Generic Error Modelling System (GEMS) (Reason 1990), takes into account the error-correcting mechanisms on the skill-, rule- and knowledge-based levels. A basic assumption of GEMS is that day-to-day behaviour implies routine behaviour. Routine behaviour is checked regularly, but between these feedback loops, behaviour is completely automatic. Since the behaviour is skill-based, the errors are slips. When the feedback shows a deviation from the desired goal, rule-based correction is applied. The problem is diagnosed on the basis of available symptoms, and a correction rule is automatically applied when the situation is diagnosed. When the wrong rule is applied there is a mistake.

When the situation is completely unknown, knowledge-based rules are applied. The symptoms are examined in the light of knowledge about the system and its components. This analysis can lead to a possible solution the implementation of which constitutes a case of knowledge-based behaviour. (It is also possible that the problem cannot be solved in a given way and that further knowledge-based rules have to be applied.) All errors on this level are mistakes. Violations are committed when a certain rule is applied that is known to be inappropriate: the thinking of the worker may be that application of an alternative rule will be less time-consuming or is possibly more suitable for the present, probably exceptional, situation. The more malevolent class of violations involves sabotage, a subject that is not within the scope of this article. When organizations are attempting to eliminate human error, they should take into account whether the errors are on the skill-, rule- or knowledge-based level, as each level requires its own techniques (Groeneweg 1996).

Influencing Human Behaviour: An Overview

A comment often made with regard to a particular accident is, “Maybe the person did not realize it at the time, but if he or she had not acted in a certain way, the accident would not have happened.” Much of accident prevention is aimed at influencing the crucial bit of human behaviour alluded to in this remark. In many safety management systems, the solutions and policies suggested are aimed at directly influencing human behaviour. However, it is very uncommon that organizations assess how effective such methods really are. Psychologists have devoted much thought to how human behaviour can best be influenced. In this respect, the following six ways of exercising control over human error will be set forth, and an evaluation will be performed of the relative effectiveness of these methods in controlling human behaviour on a long-term basis (Wagenaar 1992). (See table 1.)

Table 1. Six ways to induce safe behaviour and assessment of their cost-effectiveness

|

No. |

Way of influencing |

Cost |

Long-term effect |

Assessment |

|

1 |

Don’t induce safe behaviour, |

High |

Low |

Poor |

|

2 |

Tell those involved what to do. |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

|

3 |

Reward and punish. |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|

4 |

Increase motivation and awareness. |

Medium |

Low |

Poor |

|

5 |

Select trained personnel. |

High |

Medium |

Medium |

|

6 |

Change the environment. |

High |

High |

Good |

Do not attempt to induce safe behaviour, but make the system “foolproof”

The first option is to do nothing to influence the behaviour of people but to design the workplace in such a way that whatever the employee does, it will not result in any kind of undesirable outcome. It must be acknowledged that, thanks to the influence of robotics and ergonomics, designers have considerably improved on the user-friendliness of workplace equipment. However, it is almost impossible to anticipate all the different kinds of behaviour that people may evince. Besides, workers often regard so-called foolproof designs as a challenge to “beat the system”. Finally, as designers are human themselves, even very carefully foolproof-designed equipment can have flaws (e.g., Petroski 1992). The additional benefit of this approach relative to existing hazard levels is marginal, and in any event initial design and installation costs may increase exponentially.

Tell those involved what to do

Another option is to instruct all workers about every single activity in order to bring their behaviour fully under the control of management. This will require an extensive and not very practical task inventory and instruction control system. As all behaviour is de-automated it will to a large extent eliminate slips and lapses until the instructions become part of the routine and the effect fades away.

It does not help very much to tell people that what they do is dangerous - most people know that very well - because they will make their own choices concerning risk regardless of attempts to persuade them otherwise. Their motivation to do so will be to make their work easier, to save time, to challenge authority and perhaps to enhance their own career prospects or claim some financial reward. Instructing people is relatively cheap, and most organizations have instruction sessions before the start of a job. But beyond such an instruction system the effectiveness of this approach is assessed to be low.

Reward and punish

Although reward and punishment schedules are powerful and very popular means for controlling human behaviour, they are not without problems. Reward works best only if the recipient perceives the reward to be of value at the time of receipt. Punishing behaviour that is beyond an employee’s control (a slip) will not be effective. For example, it is more cost-effective to improve traffic safety by changing the conditions underlying traffic behaviour than by public campaigns or punishment and reward programmes. Even an increase in the chances of being “caught” will not necessarily change a person’s behaviour, as the opportunities for violating a rule are still there, as is the challenge of successful violation. If the situations in which people work invite this kind of violation, people will automatically choose the undesired behaviour no matter how they are punished or rewarded. The effectiveness of this approach is rated as of medium quality, as it usually is of short-term effectiveness.

Increase motivation and awareness

Sometimes it is believed that people cause accidents because they lack motivation or are unaware of danger. This assumption is false, as studies have shown (e.g., Wagenaar and Groeneweg 1987). Furthermore, even if workers are capable of judging danger accurately, they do not necessarily act accordingly (Kruysse 1993). Accidents happen even to people with the best motivation and the highest degree of safety awareness. There are effective methods for improving motivation and awareness which are discussed below under “Change the environment”. This option is a delicate one: in contrast with the difficulty to further motivate people it is almost too easy to de-motivate employees to the extent that even sabotage is considered.

The effects of motivation enhancement programmes are positive only when coupled with behaviour modification techniques such as employee involvement.

Select trained personnel

The first reaction to an accident is often that those involved must have been incompetent. With hindsight, the accident scenarios appear straightforward and easily preventable to someone sufficiently intelligent and properly trained, but this appearance is a deceptive one: in actual fact the employees involved could not possibly have foreseen the accident. Therefore, better training and selection will not have the desirable effect. A base level of training is however a prerequisite for safe operations. The tendency in some industries to replace experienced personnel with inexperienced and inadequately trained people is to be discouraged, as increasingly complex situations call for rule- and knowledge-based thinking that requires a level of experience that such lower-cost personnel often do not possess.

A negative side-effect of instructing people very well and selecting only the highest-classified people is that behaviour can become automatic and slips occur. Selection is expensive, while the effect is not more than medium.

Change the environment

Most behaviour occurs as a reaction to factors in the working environment: work schedules, plans, and management expectations and demands. A change in the environment results in different behaviour. Before the working environment can be effectively changed, several problems must be solved. First, the environmental factors that cause the unwanted behaviour must be identified. Second, these factors must be controlled. Third, management must allow discussion about their role in creating the adverse working environment.

It is more practical to influence behaviour through creating the proper working environment. The problems that should be solved before this solution can be put into practice are (1) that it must be known which environmental factors cause the unwanted behaviour, (2) that these factors must be controlled and (3) that previous management decisions must be considered (Wagenaar 1992; Groeneweg 1996). All these conditions can indeed be met, as will be argued in the remainder of this article. The effectiveness of behaviour modification can be high, even though a change of environment may be quite costly.

The Accident Causation Model

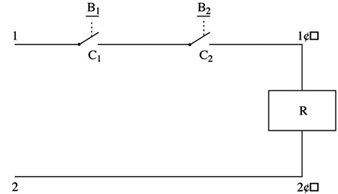

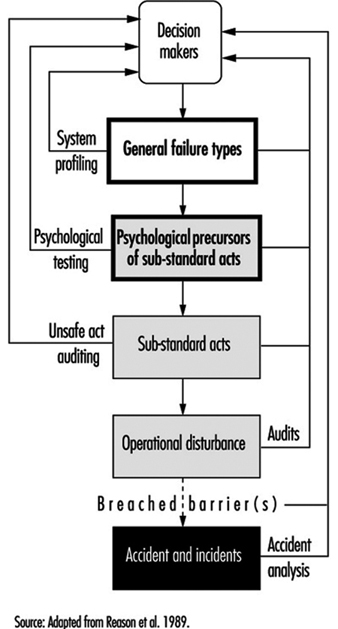

In order to get more insight into the controllable parts of the accident causation process, an understanding of the possible feedback loops in a safety information system is necessary. In figure 1, the complete structure of a safety information system is presented that can form the basis of managerial control of human error. It is an adapted version of the system presented by Reason et al. (1989).

Figure 1. A safety information system

Accident investigation

When accidents are investigated, substantial reports are produced and decision-makers receive information about the human error component of the accident. Fortunately, this is becoming more and more obsolete in many companies. It is more effective to analyse the “operational disturbances” that precede the accidents and incidents. If an accident is described as an operational disturbance followed by its consequences, then sliding from the road is an operational disturbance and getting killed because the driver did not wear a safety belt is an accident. Barriers may have been placed between the operational disturbance and the accident, but they failed or were breached or circumvented.

Unsafe act auditing

A wrong act committed by an employee is called a “substandard act” and not an “unsafe act” in this article: the notion of “unsafe” seems to limit the applicability of the term to safety, whereas it can also be applied, for example, to environmental problems. Substandard acts are sometimes recorded, but detailed information as to which slips, mistakes and violations were performed and why they were performed is hardly ever fed back to higher management levels.

Investigating the employee’s state of mind

Before a substandard act is committed, the person involved was in a certain state of mind. If these psychological precursors, like being in a state of haste or feeling sad, could be adequately controlled, people would not find themselves in a state of mind in which they would commit a substandard act. Since these states of mind cannot be effectively controlled, such precursors are regarded as “black box” material (figure 1).

General failure types

The GFT (general failure type) box in figure 1 represents the generating mechanisms of an accident - the causes of substandard acts and situations. Because these substandard acts cannot be controlled directly, it is necessary to change the working environment. The working environment is determined by 11 such mechanisms (table 2). (In the Netherlands the abbreviation GFT already exists in a completely different context, and has to do with ecologically sound waste disposal, and to avoid confusion another term is used: basic risk factors (BRFs) (Roggeveen 1994).)

Table 2. General failure types and their definitions

|

General failures |

Definitions |

|

1. Design (DE) |

Failures due to poor design of a whole plant as well as individual |

|

2. Hardware (HW) |

Failures due to poor state or unavailability of equipment and tools |

|

3. Procedures (PR) |

Failures due to poor quality of the operating procedures with |

|

4. Error enforcing |

Failures due to poor quality of the working environment, with |

|

5. Housekeeping (HK) |

Failures due to poor housekeeping |

|

6. Training (TR) |

Failures due to inadequate training or insufficient experience |

|

7. Incompatible goals(IG) |

Failures due to the poor way safety and internal welfare are |

|

8. Communication (CO) |

Failures due to poor quality or absence of lines of communication |

|

9. Organization (OR) |

Failures due to the way the project is managed |

|

10. Maintenance |

Failures due to poor quality of the maintenance procedures |

|

11. Defences (DF) |

Failures due to the poor quality of the protection against hazardous |

The GFT box is preceded by a “decision-maker’s” box, as these people determine to a large extent how well a GFT is managed. It is management’s task to control the working environment by managing the 11 GFTs, thereby indirectly controlling the occurrence of human error.

All these GFTs can contribute to accidents in subtle ways by allowing undesirable combinations of situations and actions to come together, by increasing the chance that certain persons will commit substandard acts and by failing to provide the means to interrupt accident sequences already in progress.

There are two GFTs that require some further explanation: maintenance management and defences.

Maintenance management (MM)

Since maintenance management is a combination of factors that can be found in other GFTs, it is not, strictly speaking, a separate GFT: this type of management is not fundamentally different from other management functions. It may be treated as a separate issue because maintenance plays an important role in so many accident scenarios and because most organizations have a separate maintenance function.

Defences (DF)

The category of defences is also not a true GFT, as it is not related to the accident causation process itself. This GFT is related to what happens after an operational disturbance. It does not generate either psychological states of mind or substandard acts by itself. It is a reaction that follows a failure due to the action of one or more GFTs. While it is indeed true that a safety management system should focus on the controllable parts of the accident causation chain before and not after the unwanted incident, nevertheless the notion of defences can be used to describe the perceived effectiveness of safety barriers after a disturbance has occurred and to show how they failed to prevent the actual accident.

Managers need a structure that will enable them to relate identified problems to preventive actions. Measures taken at the levels of safety barriers or substandard acts are still necessary, although these measures can never be completely successful. To trust “last line” barriers is to trust factors that are to a large extent out of management control. Management should not attempt to manage such uncontrollable external devices, but instead must try to make their organizations inherently safer at every level.

Measuring the Level of Control over Human Error

Ascertaining the presence of the GFTs in an organization will enable accident investigators to identify the weak and strong points in the organization. Given such knowledge, one can analyse accidents and eliminate or mitigate their causes and identify the structural weaknesses within a company and fix them before they in fact contribute to an accident.

Accident investigation

The task of an accident analyst is to identify contributing factors and to categorize them. The number of times a contributing factor is identified and categorized in terms of a GFT indicates the extent to which this GFT is present. This is often done by means of a checklist or computer analysis program.

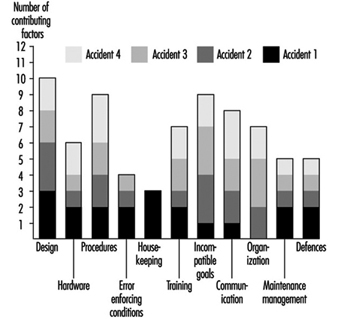

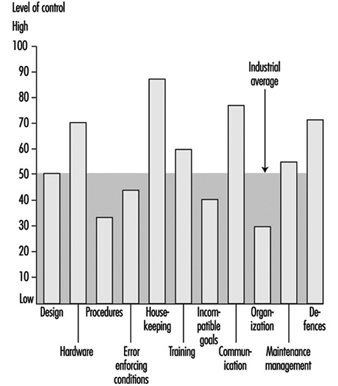

It is possible and desirable to combine profiles from different but similar types of accidents. Conclusions based upon an accumulation of accident investigations in a relatively short time are far more reliable than those drawn from a study in which the accident profile is based upon a single event. An example of such a combined profile is presented in figure 2, which shows data relating to four occurrences of one type of accident.

Figure 2. Profile of an accident type

Some of the GFTs - design, procedures and incompatible goals - score consistently high in all four particular accidents. This means that in each accident, factors have been identified that were related to these GFTs. With respect to the profile of accident 1, design is a problem. Housekeeping, although a major problem area in accident 1, is only a minor problem if more than the first accident is analysed. It is suggested that about ten similar types of accidents be investigated and combined in a profile before far-reaching and possibly expensive corrective measures are taken. This way, the identification of the contributing factors and subsequent categorization of these factors can be done in a very reliable way (Van der Schrier, Groeneweg and van Amerongen 1994).

Identifying the GFTs within an organization pro-actively

It is possible to quantify the presence of GFTs pro-actively, regardless of the occurrence of accidents or incidents. This is done by looking for indicators of the presence of that GFT. The indicator used for this purpose is the answer to a straightforward yes or no question. If answered in the undesired way, it is an indication that something is not functioning properly. An example of an indicator question is: “In the past three months, did you go to a meeting that turned out to be cancelled?” If the employee answers the question in the affirmative, it does not necessarily signify danger, but it is indicative of a deficiency in one of the GFTs—communication. However, if enough questions that test for a given GFT are answered in a way that indicates an undesirable trend, it is a signal to management that it does not have sufficient control of that GFT.

To construct a system safety profile (SSP), 20 questions for each of the 11 GFTs have to be answered. Each GFT is assigned a score ranging from 0 (low level of control) to 100 (high level of control). The score is calculated relative to the industry average in a certain geographical area. An example of this scoring procedure is presented in the box.

The indicators are pseudo-randomly drawn from a database with a few hundred questions. No two subsequent checklists have questions in common, and questions are drawn in such a way that each aspect of the GFT is covered. Failing hardware could, for instance, be the result of either absent equipment or defective equipment. Both aspects should be covered in the checklist. The answering distributions of all questions are known, and checklists are balanced for equal difficulty.

It is possible to compare scores obtained with different checklists, as well as those obtained for different organizations or departments or the same units over a period of time. Extensive validation tests have been done to ensure that all questions in the database have validity and that they are all indicative of the GFT to be measured. Higher scores indicate a higher level of control - that is, more questions have been answered in the “desired” way. A score of 70 indicates that this organization is ranked among the best 30 (i.e., 100 minus 70) of comparable organizations in this kind of industry. Although a score of 100 does not necessarily mean that this organization has total control over a GFT, it does means that with regard to this GFT the organization is the best in the industry.

An example of an SSP is shown in figure 3. The weak areas of Organization 1, as exemplified by the bars in the chart, are procedures, incompatible goals, and error enforcing conditions, as they score below the industry average as shown by the dark grey area. The scores on housekeeping, hardware and defences are very good in Organization 1. On the surface, this well-equipped and tidy organization with all safety devices in place appears to be a safe place to work. Organization 2 scores exactly at the industry average. There are no major deficiencies, and although the scores on hardware, housekeeping and defences are lower, this company manages (on the average) the human error component in accidents better than Organization 1. According to the accident causation model, Organization 2 is safer than Organization 1, although this would not necessarily be apparent in comparing the organizations in “traditional” audits.

Figure 3. Example of a system safety profile

If these organizations had to decide where to allocate their limited resources, the four areas with below average GFTs would have priority. However, one cannot conclude that, since the other GFT scores are so favourable, resources may be safely withdrawn from their upkeep, since these resources are what have most probably kept them at so high a level in the first place.

Conclusions

This article has touched upon the subject of human error and accident prevention. The overview of the literature regarding control of the human error component in accidents yielded a set of six ways by which one can try to influence behaviour. Only one, restructuring the environment or modifying behaviour in order to reduce the number of situations in which people are liable to commit an error, has a reasonably favourable effect in a well-developed industrial organization where many other attempts have already been made. It will take courage on the part of management to recognize that these adverse situations exist and to mobilize the resources that are needed to effect a change in the company. The other five options do not represent helpful alternatives, as they will have little or no effect and will be quite costly.

“Controlling the controllable” is the key principle supporting the approach presented in this article. The GFTs must be discovered, attacked and eliminated. The 11 GFTs are mechanisms that have proven to be part of the accident causation process. Ten of them are aimed at preventing operational disturbances and one (defences) is aimed at the prevention of the operational disturbance’s turning into an accident. Eliminating the impact of the GFTs has a direct bearing upon the abatement of contributing causes of accidents. The questions in the checklists are aimed at measuring the “health state” of a given GFT, from both a general and a safety point of view. Safety is viewed as an integrated part of normal operations: doing the job the way it should be done. This view is in accordance with the recent “quality oriented” management approaches. The availability of policies, procedures and management tools is not the chief concern of safety management: the question is rather whether these methods are actually used, understood and adhered to.

The approach described in this article concentrates upon systemic factors and the way in which management decisions can be translated into unsafe conditions at the workplace, in contrast to the conventional belief that attention should be directed towards the individual workers who perform unsafe acts, their attitudes, motivations and perceptions of risk.

An indication of the level of control your organization has over the GFT “Communication”

In this box a list of 20 questions is presented. The questions in this list have been answered by employees of more than 250 organizations in Western Europe. These organizations were operating in different fields, ranging from chemical companies to refineries and construction companies. Normally, these questions would be tailor-made for each branch. This list serves as an example only to show how the tool works for one of the GFTs. Only those questions have been selected that have proved to be so “general” that they are applicable in at least 80% of the industries.

In “real life” employees would not only have to answer the questions (anonymously), they would also have to motivate their answers. It is not sufficient to answer “Yes” on, for example, the indicator “Did you have to work in the past 4 weeks with an outdated procedure?” The employee would have to indicate which procedure it was and under which conditions it had to be applied. This motivation serves two goals: it increases the reliability of the answers and it provides management with information it can act upon.

Caution is also necessary when interpreting the percentile score: in a real measurement, each organization would be matched against a representative sample of branch-related organizations for each of the 11 GFTs. The distribution of percentiles is from May 1995, and this distribution does change slightly over time.

How to measure the “level of control”

Answer all 20 indicators with your own situation in mind and beware of the time limits in the questions. Some of the questions might not be applicable for your situation; answer them with “n.a.” It might be impossible for you to answer some questions; answer them with a question mark“?”.

After you have answered all questions, compare your answers with the reference answers. You get a point for each “correctly” answered question.

Add the number of points together. Calculate the percentage of correctly answered questions by dividing the number of points by the number of questions you have answered with either “Yes” or “No”. The “n.a.” and “?” answers are not taken into account. The result is a percentage between 0 and 100.

The measurement can be made more reliable by having more people answering the questions and by averaging their scores over the levels or functions in the organization or comparable departments.

Twenty questions about the GFT “Communication”

Possible answers to the questions: Y = Yes; N = No; n.a. = not applicable; ? = don’t know.

- In the past 4 weeks has the telephone directory provided you with incorrect or insufficient information?

- In the past 2 weeks has your telephone conversation been interrupted due to a malfunctioning of the telephone system?

- Have you received mail in the past week that was not relevant to you?

- Has there been an internal or external audit in the past 9 months of your office paper trail?

- Was more than 20% of the information you received in the past 4 weeks labelled “urgent”?

- Did you have to work in the past 4 weeks with a procedure that was difficult to read (e.g., phrasing or language problems)?

- Have you gone to a meeting in the past 4 weeks that turned out not to be held at all?

- Has there been a day in the past 4 weeks that you had five or more meetings?

- Is there a “suggestion box” in your organization?

- Have you been asked to discuss a matter in the past 3 months that later turned out to be already decided upon?

- Have you sent any information in the past 4 weeks that was never received?

- Have you received information in the past 6 months about changes in policies or procedures more than a month after it had been put into effect?

- Have the minutes of the last three safety meetings been sent to your management?

- Has “office” management stayed at least 4 hours at the location when making the last site visit?

- Did you have to work in the past 4 weeks with procedures with conflicting information?

- Have you received within 3 days feedback on requests for information in the past 4 weeks?

- Do people in your organization speak different languages or dialects (different mother tongue)?

- Was more than 80% of the feedback you received (or gave) from management in the past 6 months of a “negative nature”?

- Are there parts of the location/workplace where it is difficult to understand each other due to extreme noise levels?

- In the past 4 weeks, have tools and/or equipment been delivered that not had been ordered?

Reference answers:

1 = N; 2 = N; 3 = N; 4 = Y; 5 = N; 6 = N; 7 = N; 8 = N; 9 = N; 10 = N; 11 = N; 12 = N; 13 = Y; 14 = N; 15 = N; 16 = Y; 17 = N; 18 = N; 19 = Y; 20 = N.

Scoring GFT “Communication”

Percent score = (a/b) x 100

where a = no. of questions answered correctly

where b = no. of questions answered “Y” or “N”.

|

Your score % |

Percentile |

% |

Equal or better |

|

0-10 |

0-1 |

100 |

99 |

|

11-20 |

2-6 |

98 |

94 |

|

21-30 |

7-14 |

93 |

86 |

|

31-40 |

15-22 |

85 |

78 |

|

41-50 |

23-50 |

79 |

50 |

|

51-60 |

51-69 |

49 |

31 |

|

61-70 |

70-85 |

30 |

15 |

|

71-80 |

86-97 |

14 |

3 |

|

81-90 |

98-99 |

2 |

1 |

|

91-100 |

99-100 |

Hardware Hazards

This article addresses “machine” hazards, those which are specific to the appurtenances and hardware used in the industrial processes associated with pressure vessels, processing equipment, powerful machines and other intrinsically risky operations. This article does not address worker hazards, which implicate the actions and behaviour of individuals, such as slipping on working surfaces, falling from elevations and hazards from using ordinary tools. This article focuses on machine hazards, which are characteristic of an industrial job environment. Since these hazards threaten anyone present and may even be a threat to neighbours and the external environment, the analysis methods and the means for prevention and control are similar to the methods used to deal with risks to the environment from industrial activities.

Machine Hazards

Good quality hardware is very reliable, and most failures are caused by secondary effects like fire, corrosion, misuse and so on. Nevertheless, hardware may be highlighted in certain accidents, because a failing hardware component is often the most conspicuous or visibly prominent link of the chain of events. Although the term hardware is used in a broad sense, illustrative examples of hardware failures and their immediate “surroundings” in accident causation have been taken from industrial workplaces. Typical candidates for investigation of “machine” hazards include but are not limited to the following:

- pressure vessels and pipes

- motors, engines, turbines and other rotating machines

- chemical and nuclear reactors

- scaffolding, bridges, etc.

- lasers and other energy radiators

- cutting and drilling machinery, etc.

- welding equipment.

Effects of Energy

Hardware hazards can include wrong use, construction errors or frequent overload, and accordingly their analysis and mitigation or prevention can follow rather different directions. However, physical and chemical energy forms that elude human control often exist at the heart of hardware hazards. Therefore, one very general method to identify hardware hazards is to look for the energies that are normally controlled with the actual piece of equipment or machinery, such as a pressure vessel containing ammonia or chlorine. Other methods use the purpose or intended function of the actual hardware as a starting point and then look for the probable effects of malfunctions and failures. For example, a bridge failing to fulfil its primary function will expose subjects on the bridge to the risk of falling down; other effects of the collapse of a bridge will be the secondary ones of falling items, either structural parts of the bridge or objects situated on the bridge. Further down the chain of consequences, there may be derived effects related to functions in other parts of the system that were dependent on the bridge performing its function properly, such as the interruption of emergency response vehicular traffic to another incident.

Besides the concepts of “controlled energy” and “intended function”, dangerous substances must be addressed by asking questions such as, “How could agent X be released from vessels, tanks or pipe systems and how could agent Y be produced?” (either or both may be hazardous). Agent X might be a pressurized gas or a solvent, and agent Y might be an extremely toxic dioxin whose formation is favoured by the “right” temperatures in some chemical processes, or it could be produced by rapid oxidation, as the result of a fire. However, the possible hazards add up to much more than just the risks of dangerous substances. Conditions or influences might exist which allow the presence of a particular item of hardware to lead to harmful consequences to humans.

Industrial Work Environment

Machine hazards also involve load or stress factors that may be dangerous in the long run, such as the following:

- extreme working temperatures

- high intensities of light, noise or other stimuli

- inferior air quality

- extreme job demands or workloads.

These hazards can be recognized and precautions taken because the dangerous conditions are already there. They do not depend on some structural change in the hardware to come about and work a harmful result, or on some special event to effect damage or injury. Long-term hazards also have specific sources in the working environment, but they must be identified and evaluated through observing workers and the jobs, instead of just analysing hardware construction and functions.

Dangerous hardware or machine hazards are usually exceptional and rather seldom found in a sound working environment, but cannot be avoided completely. Several types of uncontrolled energy, such as the following risk agents, can be the immediate consequence of hardware malfunction:

- harmful releases of dangerous gas, liquids, dusts or other substances

- fire and explosion

- high voltages

- falling objects, missiles, etc.

- electric and magnetic fields

- cutting, trapping, etc.

- displacement of oxygen

- nuclear radiation, x rays and laser light

- flooding or drowning

- jets of hot liquid or steam.

Risk Agents

Moving objects. Falling and flying objects, liquid flows and jets of liquid or steam, such as listed, are often the first external consequences of hardware or equipment failure, and they account for a large proportion of accidents.

Chemical substances. Chemical hazards also contribute to worker accidents as well as affecting the environment and the public. The Seveso and Bhopal accidents involved chemical releases which affected numerous members of the public, and many industrial fires and explosions release chemicals and fumes to the atmosphere. Traffic accidents involving gasoline or chemical delivery trucks or other dangerous goods transports, unite two risk agents - moving objects and chemical substances.

Electromagnetic energy. Electric and magnetic fields, x rays and gamma rays are all manifestations of electromagnetism, but are often treated separately as they are encountered under rather different circumstances. However, the dangers of electromagnetism have some general traits: fields and radiation penetrate human bodies instead of just making contact on the application area, and they cannot be sensed directly, although very large intensities cause heating of the affected body parts. Magnetic fields are created by the flow of electric current, and intense magnetic fields are to be found in the vicinity of large electric motors, electric arc welding equipment, electrolysis apparatus, metal works and so forth. Electric fields accompany electric tension, and even the ordinary mains voltages of 200 to 300 volts cause the accumulation of dirt over several years, the visible sign of the field’s existence, an effect also known in connection with high-tension electrical lines, TV picture tubes, computer monitors and so on.

Electromagnetic fields are mostly found rather close to their sources, but electromagnetic radiation is a long-distance traveller, as radar and radio waves exemplify. Electromagnetic radiation is scattered, reflected and damped as it passes through space and meets intervening objects, surfaces, different substances and atmospheres, and the like; its intensity is therefore reduced in several ways.

The general character of the electromagnetic (EM) hazard sources are:

- Instruments are needed to detect the presence of EM fields or EM radiation.

- EM does not leave primary traces in the form of “contamination”.

- Dangerous effects are usually delayed or long-term, but immediate burns are caused in severe cases.

- X rays and gamma rays are damped, but not stopped, by lead and other heavy elements.

- Magnetic fields and x rays are stopped immediately when the source is de-energized or the equipment turned off.

- Electric fields can survive for long periods after turning the generating systems off.

- Gamma rays come from nuclear processes, and these radiation sources cannot be turned off as can many EM sources.

Nuclear radiation. The hazards associated with nuclear radiation are of special concern to workers in nuclear power plants and in plants working with nuclear materials such as fuel manufacturing and the reprocessing, transport and storage of radioactive matter. Nuclear radiation sources are also used in medicine and by some industries for measurement and control. One most common usage is in fire alarms/smoke detectors, which use an alpha-particle emitter like americium to monitor the atmosphere.

Nuclear hazards are principally centred around five factors:

- gamma rays

- neutrons

- beta particles (electrons)

- alpha particles (helium nuclei)

- contamination.

The hazards arise from the radioactive processes in nuclear fission and the decaying of radioactive materials. This sort of radiation is emitted from reactor processes, reactor fuel, reactor moderator material, from the gaseous fission products that may be developed, and from certain construction materials that become activated by exposure to radioactive emissions arising from reactor operation.

Other risk agents. Other classes of risk agents that release or emit energy include:

- UV radiance and laser light

- infrasound

- high-intensity sound

- vibration.

Triggering the Hardware Hazards

Both sudden and gradual shifts from the controlled - or “safe” - condition to one with increased danger can come about through the following circumstances, which can be controlled through appropriate organizational means such as user experience, education, skills, surveillance and equipment testing:

- wear and overloads

- external impact (fire or impact)

- ageing and failure

- wrong supply (energy, raw materials)

- insufficient maintenance and repair

- control or process error

- misuse or misapplication

- hardware breakdown

- barrier malfunction.

Since proper operations cannot reliably compensate for improper design and installation, it is important to consider the entire process, from selection and design through installation, use, maintenance and testing, in order to evaluate the actual state and conditions of the hardware item.

Hazard Case: The Pressurized Gas Tank

Gas can be contained in suitable vessels for storage or transport, like the gas and oxygen cylinders used by welders. Often, gas is handled at high pressure, affording a great increase in the storing capacity, but with higher accident risk. The key accidental phenomenon in pressurized gas storage is the sudden creation of a hole in the tank, with these results:

- the confinement function of the tank ceases

- the confined gas gets immediate access to the surrounding atmosphere.

The development of such an accident depends on these factors:

- the type and amount of gas in the tank

- the situation of the hole in relation to the tank’s contents

- the initial size and subsequent growth rate of the hole

- the temperature and pressure of the gas and the equipment

- the conditions in the immediate environment (sources of ignition, people, etc.).

The tank contents can be released almost immediately or over a period of time, and result in different scenarios, from the burst of free gas from a ruptured tank, to moderate and rather slow releases from small punctures.

The behaviour of various gases in the case of leakage

When developing release calculation models, it is most important to determine the following conditions affecting the system’s potential behaviour:

- the gas phase behind the hole (gaseous or liquid?)

- temperature and wind conditions

- the possible entry of other substances into the system or their possible presence in its surroundings

- barriers and other obstacles.

The exact calculations pertaining to a release process where liquefied gas escapes from a hole as a jet and then evaporates (or alternatively, first becomes a mist of droplets) are difficult. The specification of the later dispersion of the resultant clouds is also a difficult problem. Consideration must be given to the movements and dispersion of gas releases, whether the gas forms visible or invisible clouds and whether the gas rises or stays at ground level.

While hydrogen is a light gas compared to any atmosphere, ammonia gas (NH3, with a molecular weight of 17.0) will rise in an ordinary air-like, oxygen-nitrogen atmosphere at the same temperature and pressure. Chlorine (Cl2, with a molecular weight of 70.9) and butane (C4H10, mol. wt.58) are examples of chemicals whose gas phases are denser than air, even at ambient temperature. Acetylene (C2H2, mol. wt. 26.0) has a density of about 0.90g/l, approaching that of air (1.0g/l), which means that in a working environment, leaking welding gas will not have a pronounced tendency to float upwards or to sink downwards; therefore it can mix easily with the atmosphere.

But ammonia released from a pressure vessel as a liquid will at first cool as a consequence of its evaporation, and may then escape via several steps:

- Pressurized, liquid ammonia emanates from the hole in tank as jet or cloud.

- Seas of liquid ammonia can be formed on the nearest surfaces.

- The ammonia evaporates, thereby cooling itself and the near environment.

- Ammonia gas gradually exchanges heat with surroundings and equilibrates with ambient temperatures.

Even a cloud of light gas may not rise immediately from a liquid gas release; it may first form a fog - a cloud of droplets - and stay near the ground. The gas cloud’s movement and gradual mixing/dilution with the surrounding atmosphere depends on weather parameters and on the surrounding environment—enclosed area, open area, houses, traffic, presence of the public, workers and so on.

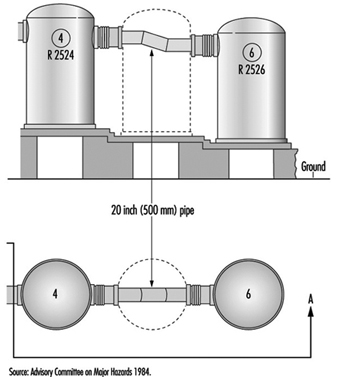

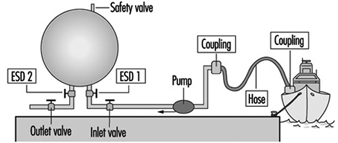

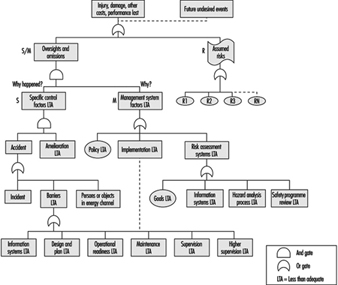

Tank Failure