Wallerstein, Nina

Address: University of New Mexico, 2400 Tucker Avenue NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5241

Country: United States

Phone: 1 (505) 272-4173

Fax: 1 (505) 272-4494

E-mail: nwall@unm.edu

Past position(s): Assistant Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, UNM

Education: BA, 1976, University of California-Berkeley; MPH, 1980, University of California-Berkeley; DrPH, 1988, University of California-Berkeley

Areas of interest: Empowerment education; popular education; methodology; health and safety education and evaluation; community evaluation

Evaluating Health and Safety Training: A Case Study in Chemical Workers Hazardous Waste Worker Education

Until very recently the effectiveness of training and education in controlling occupational health and safety hazards was largely a matter of faith rather than systematic evaluation (Vojtecky and Berkanovic 1984-85; Wallerstein and Weinger 1992). With the rapid expansion of intensive federally-funded training and education programmes in the past decade in the United States, this has begun to change. Educators and researchers are applying more rigorous approaches to evaluating the actual impact of worker training and education on outcome variables such as accident, illness and injury rates and on intermediate variables such as the ability of workers to identify, handle and resolve hazards in their workplaces. The programme that combines chemical emergency training as well as hazardous waste training of the International Chemical Workers Union Center for Worker Health and Safety Education provides a useful example of a well-designed programme which has incorporated effective evaluation into its mission.

The Center was established in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1988 under a grant which the International Chemical Workers Union (ICWU) received from the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences to provide training for hazardous waste and emergency response workers. The Center is a cooperative venture of six industrial unions, a local occupational health centre and a university environmental health department. It adopted an empowerment education approach to training and defines its mission broadly as:

… promoting worker abilities to solve problems and to develop union-based strategies for improving health and safety conditions at the worksite (McQuiston et al. 1994).

To evaluate the programme’s effectiveness in this mission the Center conducted long-term follow-up studies with the workers who went through the programme. This comprehensive evaluation went considerably beyond the typical assessment which is conducted immediately following training, and measures trainees’ short-term retention of information and satisfaction with (or reaction to) the education.

Programme and Audience

The course that was the subject of evaluation is a four or five-day chemical emergency/hazardous waste training programme. Those attending the courses are members of six industrial unions and a smaller number of management personnel from some of the plants represented by the unions. Workers who are exposed to substantial releases of hazardous substances or who work with hazardous waste less proximately are eligible to attend. Each class is limited to 24 students so as to promote discussion. The Center encourages local unions to send three or four workers from each site to the course, believing that a core group of workers is more likely than an individual to work effectively to reduce hazards when they return to the workplace.

The programme has established interrelated long-term and short-term goals:

Long-term goal: for workers to become and remain active participants in determining and improving the health and safety conditions under which they work.

Immediate educational goal: to provide students with relevant tools, problem-solving skills, and the confidence needed to use those tools (McQuiston et al. 1994).

In keeping with these goals, instead of focusing on information recall, the programme takes a “process oriented” training approach which seeks “to build self-reliance that stresses knowing when additional information is needed, where to find it, and how to interpret and use it.” (McQuiston et al. 1994.)

The curriculum includes both classroom and hands-on training. Instructional methods emphasize small group problem-solving activities with the active participation of the workers in the training. The development of the course also employed a participatory process involving rank-and-file safety and health leaders, programme staff and consultants. This group evaluated initial pilot courses and recommended revisions of the curriculum, materials and methods based on extensive discussions with trainees. This formative evaluation is an important step in the evaluation process that takes place during programme development, not at the end of the programme.

The course introduces the participants to a range of reference documents on hazardous materials. Students also develop a “risk chart” for their own facility during the course, which they use to evaluate their plant’s hazards and safety and health programmes. These charts form the basis for action plans which create a bridge between what the students learn at the course and what they decide needs to be implemented back in the workplace.

Evaluation Methodology

The Center conducts anonymous pre-training and post-training knowledge tests of participants to document increased levels of knowledge. However, to determine the long-term effectiveness of the programme the Center uses telephone follow-up interviews of students 12 months after training. One attendee from each local union is interviewed while every manager attendee is interviewed. The survey measures outcomes in five major areas:

- students’ ongoing use of resource and reference materials introduced during training

- the amount of secondary training, that is, training conducted by participants for co-workers back at the worksite following attendance at the Center course

- trainee attempts and successes in obtaining changes in worksite emergency response or hazardous waste programmes, procedures or equipment

- post-training improvements in the way spills are handled at the worksite

- students' perceptions of training programme effectiveness.

The most recent published results of this evaluation are based on 481 union respondents, each representing a distinct worksite, and 50 management respondents. The response rates to the interviews were 91.9% for union respondents and 61.7% for management.

Results and Implications

Use of resource materials

Of the six major resource materials introduced in the course, all except the risk chart were used by at least 60% of the union and management trainees. The NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards and the Center’s training manual were the most widely used.

Training of co-workers

Almost 80% of the union trainees and 72% of management provided training to co-workers back at the worksite. The average number of co-workers taught (70) and the average length of training (9.7 hours) were substantial. Of special significance was that more than half of the union trainees taught managers at their worksites. Secondary training covered a wide range of topics, including chemical identification, selection and use of personal protective equipment, health effects, emergency response and use of reference materials.

Obtaining worksite improvements

The interviews asked a series of questions related to attempts to improve company programmes, practices and equipment in 11 different areas, including the following seven especially important ones:

- health effects training

- availability of material safety data sheets

- chemical labelling

- respirator availability, testing and training

- gloves and protective clothing

- emergency response

- decontamination procedures.

The questions determined whether respondents felt changes were needed and, if so, whether improvements had been made.

In general, union respondents felt greater need for and attempted more improvements than management, although the degree of difference varied with specific areas. Still fairly high percentages of both unions and management reported attempted improvements in most areas. Success rates over the eleven areas ranged from 44 to 90% for unionists and from 76 to 100% for managers.

Spill response

Questions concerning spills and releases were intended to ascertain whether attendance at the course had changed the way spills were handled. Workers and managers reported a total of 342 serious spills in the year following their training. Around 60% of those reporting spills indicated that the spills were handled differently because of the training. More detailed questions were subsequently added to the survey to collect additional qualitative and quantitative data. The evaluation study provides workers’ comments on specific spills and the role the training played in responding to them. Two examples are quoted below:

Following training the proper equipment was issued. Everything was done by the books. We have come a long way since we formed a team. The training was worthwhile. We don’t have to worry about the company, now we can judge for ourselves what we need.

The training helped by informing the safety committee about the chain of command. We are better prepared and coordination through all departments has improved.

Preparedness

The great majority of union and management respondents felt that they are “much better” or “somewhat better” prepared to handle hazardous chemicals and emergencies as a result of the training.

Conclusion

This case illustrates many of the fundamentals of training and education programme design and evaluation. The goals and objectives of the educational programme are explicitly stated. Social action objectives regarding workers’ ability to think and act for themselves and advocate for systemic changes are prominent along with the more immediate knowledge and behaviour objectives. The training methods are chosen with these objectives in mind. The evaluation methods measure the achievement of these objectives by discovering how the trainees applied the material from the course in their own work environments over the long term. They measure training impact on specific outcomes such as spill response and on intermediate variables such as the extent to which training is passed on to other workers and how course participants use resource materials.

Worker Education and Training

Worker training in occupational safety and health may serve many different purposes. Too often, worker training is viewed only as a way to comply with governmental regulations or to reduce insurance costs by encouraging individual workers to follow narrowly defined safe work behaviours. Worker education serves a far broader purpose when it seeks to empower workers to take an active part in making the workplace safe, rather than simply to encourage worker compliance with management safety rules.

Over the past two decades, there has been a move in many countries toward the concept of broad worker involvement in safety and health. New regulatory approaches rely less on government inspectors alone to enforce safety and health on the job. Labour unions and management are increasingly encouraged to collaborate in promoting safety and health, through joint committees or other mechanisms. This approach requires a skilled and well-informed workforce that can interact directly with management on issues of safety and health.

Fortunately, there are many international models for training workers in the full range of skills necessary to participate broadly in workplace health and safety efforts. These models have been developed by a combination of labour unions, university-based labour education programmes and community-based non-governmental organizations. Many innovative worker training programmes were developed originally with financing from special government grant programmes, union funds or employer contributions to collectively bargained safety and health funds.

These participatory worker training programmes, designed in a variety of national settings for diverse worker populations, share a general approach to training. The educational philosophy is based on sound adult education principles and draws upon the empowerment philosophy of “popular education”. This article describes the educational approach and its implications for designing effective worker training.

Educational Approach

Two disciplines have influenced the development of labour-oriented safety and health education programmes: the field of labour education and, more recently, the field of “popular” or empowerment education.

Labour education began simultaneously with the trade union movement in the 1800s. Its early goals were directed towards social change, that is, to promote union strength and the integration of working people into political and union organizing. Labour education has been defined as a “specialized branch of adult education that attempts to meet the educational needs and interests arising out of workers’ participation in the union movement”. Labour education has proceeded according to well-recognized principles of adult learning theory, including the following:

- Adults are self-motivated, especially with information that has immediate application to their lives and work. They expect, for example, practical tools to help them solve problems in the workplace.

- Adults learn best by building on what they already know so that they can incorporate new ideas into their existing, vast reservoir of learning. Adults wish to be respected for their experience in life. Therefore, effective methods draw on participants' own knowledge and encourage reflection on their knowledge base.

- Adults learn in different ways. Each person has a particular learning style. An educational session will work best if participants have the opportunity to engage in multiple learning modalities: to listen, look at visuals, ask questions, simulate situations, read, write, practice with equipment and discuss critical issues. Variety not only ensures that each cognitive style is addressed but also provides repetition to reinforce learning and, of course, combats boredom.

- Adults learn best when they are actively engaged, when they “learn by doing”. They are more responsive to active, participatory methods than to passive measures. Lectures and written materials have their place in a full repertoire of methods. But case studies, role plays, hands-on simulations and other small-group activities that allow each individual to be involved are more likely to result in the retention and application of new learning. Ideally, each session involves interaction between participants and includes occasions for learning new information, for applying new skills and for discussing causes of problems and barriers to solving them. Participatory methods require more time, smaller groups and perhaps different instructional skills than those that many trainers currently possess. But to increase the impact of education, active participation is essential.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, worker safety and health training has also been influenced by the perspective of “popular” or “empowerment” education. Popular education since the 1960s has developed largely from the philosophy of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. It is an approach to learning that is participatory and is based on the reality of student/worker experiences in their worksites. It fosters dialogue between educators and workers; critically analyses the barriers to change, such as organizational or structural causes of problems; and has worker action and empowerment as its goals. These tenets of popular education incorporate the basic principles of adult education, yet stress the role of worker action in the educational process, both as a goal to improve worksite conditions and as a mechanism for learning.

Participatory education in an empowerment context is more than small group activities that involve students/workers in active learning within the classroom. Participatory popular education means students/workers have the opportunity to acquire analytic and critical thinking skills, practice social action skills and develop the confidence to develop strategies for the improvement of the work environment long after the education sessions end.

Design of Education Programmes

It is important to realize that education is a continuing process, not a one-time event. It is a process that requires careful and skilful planning though each major stage. To implement a participatory education process that is based on sound adult education principles and that empowers workers, certain steps must be taken for planning and implementing participatory worker education which are similar to those used in other training programmes (see “Principles of Training”), but require special attention to meeting the goal of worker empowerment:

Step one: Assess needs

Needs assessment forms the foundation for the entire planning process. A thorough needs assessment for worker training includes three components: a hazards assessment, a profile of the target population and background on the social context of training. The hazards assessment is aimed at identifying high-priority problems to be addressed. The target population profile attempts to answer a broad set of questions about the workforce: Who can most benefit from training? What training has the target population already received? What knowledge and experience will the trainees bring to the process? What is the ethnic and gender makeup of the workforce? What is the literacy level of the workers and what languages do they speak? Whom do they respect and whom do they mistrust? Finally, gathering information on the social context of training allows the trainer to maximize the impact of training by looking at the forces that may support improved safety and health conditions (such as strong union protection that allow workers to speak out freely about hazards) and those that may pose barriers (such as productivity pressures or lack of job security).

Needs assessment can be based on questionnaires, review of documents, observations made in the workplace and interviews with workers, their union representatives and others. The popular education approach utilizes an ongoing “listening” process to gather information about the social context of training, including people's concerns and the obstacles that might inhibit change.

Step two: Gain support

Successful worker education programmes rely on identifying and involving key actors. The target population must be involved in the planning process; it is difficult to gain their trust without having sought their input. In a popular education model, the educator attempts to develop a participatory planning team from the union or shop floor who can provide ongoing advice, support, networking and a check on the validity of the needs assessment findings.

Labour unions, management and community-based groups are all potential providers of worker safety and health education. Even if not sponsoring the training directly, each of these groups may have a key role to play in supporting the educational effort. The union can provide access to the workforce and back up the efforts for change that hopefully will emerge from the training. Union activists who are respected for their knowledge or commitment can assist in outreach and help ensure a successful training outcome. Management is able to provide paid released time for training and may more readily support efforts to improve safety and health that grow out of a training process they have “bought into”. Some employers understand the importance and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive worker training in safety and health, while others will not participate without government-mandated training requirements or a collectively bargained right to paid educational leave for safety and health training.

Community-based non-governmental organizations can provide training resources, support or follow-up activities. For non-union workers, who may be especially vulnerable to retaliation for safety and health advocacy on the job, it is particularly important to identify community support resources (such as religious groups, environmentalist organizations, disabled worker support groups or minority workers’ rights projects). Whoever has a significant role to play must be involved in the process through co-sponsorship, participation on an advisory committee, personal contact or other means.

Step three: Establish education objectives and content

Using information from the needs assessment, the planning team can identify specific learning objectives. A common mistake is to assume that the objective of workshops is simply to present information. What is presented matters less than what the target population receives. Objectives should be stated in terms of what workers will know, believe, be able to do or accomplish as a result of the training. The majority of traditional training programmes focus on objectives to change the individuals' knowledge or behaviours. The goal of popular worker education is to create an activist workforce that will advocate effectively for a healthier work environment. Popular education objectives may include learning new information and skills, changing attitudes and adopting safe behaviours. However, the ultimate goal is not individual change, but collective empowerment and workplace change. The objectives leading to this goal include the following:

- Information objectives are geared towards the specific knowledge the learner will receive, for example, information about the health hazards of solvents.

- Skill objectives are intended to ensure that participants can do specific tasks that they will need to be able to perform back on the job. These can range from individual, technical skills (such as how to lift properly) to group action skills (such as how to advocate for ergonomic redesign of the workplace). Empowerment-oriented education emphasizes social action skills over mastery of individual tasks.

- Attitude objectives aim to have an impact on what the worker believes. They are important for ensuring that people move beyond their own barriers to change so that they are able to actually put their new-found knowledge and skills to use. Examples of attitudes that may be addressed include beliefs that accidents are caused by the careless worker, that workers are apathetic and do not care about safety and health or that things never change and nothing one can do will make a difference.

- Individual behavioural objectives aim to affect not just what a worker can do, but what a worker actually does back on the job as a result of training. For example, a training programme with behavioural objectives would aim to have a positive impact on respirator use on the job, not just to convey information in the classroom as to how to use a respirator properly. The problem with individual behaviour change as an objective is that workplace safety and health improvements rarely take place on an individual level. One can use a respirator properly only if the right respirator is provided and if there is time allowed for taking all necessary precautions, regardless of production pressures.

- Social action objectives also aim to have an effect on what the worker will do back on the job but address the goal of collective action for change in the work environment, rather than individual behaviour change. Actions that result from such training can range from small steps, such as investigating one specific hazard, to large undertakings, such as starting an active safety and health committee or campaigning to redesign a dangerous work process.

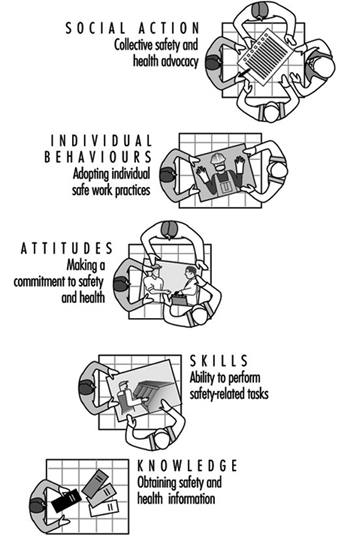

There is a hierarchy of these objectives (figure 1). Compared with the other training objectives, knowledge objectives are the easiest to achieve (but they are by no means easy to attain in an absolute sense); skill objectives require more hands-on training to ensure mastery; attitude objectives are more difficult because they may involve challenging deeply held beliefs; individual behaviour objectives are achievable only if attitude barriers are addressed and if performance, practice and on-the-job follow-up are built into the training; and social action objectives are most challenging of all, because training must also prepare participants for collective action in order to achieve more than they can on an individual basis.

Figure 1. Hierarchy of training objectives.

For example, it is a reasonably straightforward task to communicate the risks that asbestos poses to workers. The next step is to ensure that they have the technical skills to follow all safety procedures on the job. It is more difficult still to change what workers believe (e.g., to convince them that they and their fellow workers are at risk and that something can and should be done about it). Even armed with the right skills and attitudes, it may be difficult for workers to actually follow safe work practices on the job, especially since they may lack the proper equipment or management support. The ultimate challenge is to promote social action, so that workers may gain the skills, confidence and willingness to insist on using less hazardous substitute materials or to demand that all necessary environmental controls be used when they are working with asbestos.

Empowerment-oriented labour education always aims to have an impact on the highest level—social action. This requires that workers develop critical thinking and strategic planning skills that will allow them to set achievable goals, constantly respond to barriers and reshape their plans as they go. These are complex skills that require the most intensive, hands-on approach to training, as well as strong on-going support that the workers will need in order to sustain their efforts.

The specific content of educational programmes will depend on the needs assessment, regulatory mandates and time considerations. Subject areas that are commonly addressed in worker training include the following:

- health hazards of relevant exposures (such as noise, chemicals, vibration, heat, stress, infectious diseases and safety hazards)

- hazard identification methods, including means of obtaining and interpreting data regarding workplace conditions

- control technologies, including engineering and work organization changes, as well as safe work practices and personal protective equipment

- legal rights, including those relating to regulatory structures, the worker’s right to know about job hazards, the right to file a complaint and the right to compensation for injured workers

- union safety and health provisions, including collectively bargained agreements giving members the right to a safe environment, the right to information and the right to refuse to perform under hazardous conditions

- union, management, government and community resources

- the roles and responsibilities of safety and health committee members

- prioritizing hazards and developing strategies to improve the worksite, including analysis of possible structural or organizational barriers and design of action plans

Step four: Select education methods

It is important to select the right methods for the chosen objectives and content areas. In general, the more ambitious the objectives, the more intensive the methods must be. Whatever methods are selected, the profile of the workforce must be considered. For example, educators need to respond to workers’ language and literacy levels. If literacy is low, the trainer should use oral methods and highly graphic visuals. If a variety of languages is in use among the target population the trainer should use a multilingual approach.

Because of time limitations, it may not be possible to present all of the relevant information. It is more important to provide a good mix of methods to enable workers to acquire research skills and to develop social action strategies so that they can pursue their own knowledge, rather than attempt to condense too much information into a short period of time.

The teaching methods chart (see table 1) provides a summary of different methods and the objectives which each might fulfil. Some methods, such as lectures or informational films, primarily fulfil knowledge objectives. Worksheets or brainstorming exercises can fulfil information or attitude objectives. Other more comprehensive methods, such as case studies, role-plays or short videotapes that trigger discussion may be aimed at social action objectives, but may also contain new information and may present opportunities to explore attitudes.

Table 1. Teaching methods chart

| Teaching methods | Strengths | Limitations | Objectives achieved |

| Lecture | Presents factual material in direct and logical manner. Contains experiences which inspire. Stimulates thinking to open a discussion. For large audiences. |

Experts may not always be good teachers. Audience is passive. Learning difficult to gauge. Needs clear introduction and summary. |

Knowledge |

| Worksheets and questionnaires | Allow people to think for themselves without being influenced by others in discussion. Individual thoughts can then be shared in small or large groups. |

Can be used only for short period of time. Handout requires preparation time. Requires literacy. | Knowledge Attitudes/emotions |

| Brainstorming | Listening exercise that allows creative thinking for new ideas. Encourages full participation because all ideas equally recorded. | Can become unfocused. Needs to be limited to 10 to 15 minutes. |

Knowledge Attitudes/emotions |

| Planning deck | Can be used to quickly catalogue information. Allows students to learn a procedure by ordering its component parts. Group planning experience. |

Requires planning and creation of multiple planning decks. | Knowledge |

| Risk mapping | Group can create visual map of hazards, controls, and plans for action. Useful as follow-up tool. |

Requires workers from same or similar workplace. May require outside research. |

Knowledge Skills/social action |

| Audiovisual materials (films, slide shows, etc.) | Entertaining way of teaching content and raising issues. Keeps audience’s attention. Effective for large groups. |

Too many issues often presented at one time. Too passive if not combined with discussion. |

Knowledge/skills |

| Audiovisuals as triggers | Develops analytic skills. Allows for exploration of solutions. |

Discussion may not have full participation. | Social action Attitudes/emotions |

| Case studies as triggers | Develops analytic and problem-solving skills. Allows for exploration of solutions. Allows students to apply new knowledge and skills. |

People may not see relevance to own situation. Cases and tasks for small groups must be clearlydefined to be effective. |

Social action Attitudes/emotions Skills |

| Role playing session (trigger) | Introduces problem-situation dramatically. Develops analytic skills. Provides opportunity for people to assume roles of others. Allows for exploration of solutions. |

People may be too self-conscious. Not appropriate for large groups. |

Social action Attitudes/emotions Skills |

| Report back session | Allows for large group discussion of role plays, case studies, and small group exercise. Gives people a chance to reflect on experience. | Can be repetitive if each small group says the same thing. Instructors need to prepare focused questions to avoid repetitiveness. | Social action skills Information |

| Prioritizing and planning activity | Ensures participation by students. Provides experience in analysing and prioritizing problems. Allows for active discussion and debate. | Requires a large wall or blackboard for posting. Posting activity should proceed at a lively pace to be effective. | Social action Skills |

| Hands-on practice | Provides classroom practise of learned behaviour. | Requires sufficient time, appropriate physical space, and equipment. | Behaviours Skills |

Adapted from: Wallerstein and Rubenstein 1993. By permission.

Step five: Implementing an education session

Actually conducting a well-designed education session becomes the easiest part of the process; the educator simply carries out the plan. The educator is a facilitator who takes the learners through a series of activities designed to (a) learn and explore new ideas or skills, (b) share their own thoughts and abilities and (c) combine the two.

For popular education programmes, based on active participation and sharing of worker’s own experiences, it is critical that workshops establish a tone of trust, safety in discussion and ease of communication. Both physical and social environments need to be well planned to allow for maximum interaction, small group movement and confidence that there is a shared group norm of listening and willingness to participate. For some educators, this role of learning facilitator may require some “retooling”. It is a role that relies less on a talent for effective public speaking, the traditional centrepiece of training skills, and more on an ability to foster cooperative learning.

The use of peer trainers is gaining in popularity. Training workers to train their peers has two major advantages: (1) worker trainers have the practical knowledge of the workplace to make training relevant and (2) peer trainers remain in the workplace to provide on-going safety and health consultation. The success of peer trainer programmes is dependent on providing a solid foundation for worker trainers through comprehensive “training of trainer” programmes and access to technical experts when needed.

Step six: Evaluate and follow up

Though often overlooked in worker education, evaluation is essential and serves several purposes. It allows the learner to judge his or her progress toward new knowledge, skills, attitudes or actions; it allows the educator to judge the effectiveness of the training and to decide what has been accomplished; and it can document the success of training to justify future expenditures of resources. Evaluation protocols should be set up in concert with the education objectives. An evaluation effort should tell you whether or not you have achieved your training objectives.

The majority of evaluations to date have assessed immediate impact, such as knowledge learned or degree of satisfaction with the workshop. Behaviour-specific evaluations have used observations at the worksite to assess performance.

Evaluations that look at workplace outcomes, particularly injury and illness incidence rates, can be deceptive. For example, management safety promotion efforts often include incentives for keeping accident rates low (e.g., by offering a prize to the crew with the least accidents in a year). These promotional efforts result in under-reporting of accidents and often do not represent actual safety and health conditions on the job. Conversely, empowerment-oriented training encourages workers to recognize and report safety and health problems and may result, at first, in an increase in reported injuries and illnesses, even when safety and health conditions are actually improving.

Recently, as safety and health training programmes have begun to adopt empowerment and popular education goals and methods, evaluation protocols have been broadened to include assessment of worker actions back at the worksite as well as actual worksite changes. Social action objectives require long-term evaluation that assesses changes on both the individual level and on the environmental and organization level, and the interaction between individual and environmental change. Follow-up is critical for this long-term evaluation. Follow-up phone calls, surveys or even new sessions may be used not only to assess change, but also to support the students/workers in applying their new knowledge, skills, inspiration or social action resulting from training.

Several programmatic components have been identified as important for promoting actual behavioural and worksite changes: union support structures; equal union participation with management; full access to training, information and expert resources for workers and their unions; conducting training within the context of a structure for comprehensive changes; programme development based on worker and workplace needs assessments; use of worker-produced materials; and integration of small group interactive methods with worker empowerment and social action goals.

Conclusion

In this article, the growing need for preparing workers for broad participation in workplace injury and illness prevention efforts has been depicted as well as the critical role of workers as advocates for safety and health. The distinct role of labour empowerment training in responding to these needs and the educational principles and traditions that contribute to a labour empowerment approach to education were addressed. Finally, a step-by-step educational process that is required to achieve the goals of worker involvement and empowerment was described.

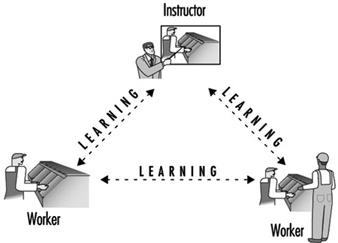

This learner-centred approach to education implies a new relationship between occupational safety and health professionals and workers. Learning can no longer be a one-way street with an “expert” imparting knowledge to the “students”. The educational process, instead, is a partnership. It is a dynamic process of communication that taps the skills and knowledge of workers. Learning occurs in all directions: workers learn from the instructors; instructors learn from workers; and workers learn from one another (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Learning is a three-way process.

For a successful partnership, workers must be involved in every stage of the educational process, not just in the classroom. Workers must participate in the who, what, where, when and how of training: Who will design and deliver the training? What will be taught? Who will pay for it? Who will have access to it? Where and when will training take place? Whose needs will be met and how will success be measured?

" DISCLAIMER: The ILO does not take responsibility for content presented on this web portal that is presented in any language other than English, which is the language used for the initial production and peer-review of original content. Certain statistics have not been updated since the production of the 4th edition of the Encyclopaedia (1998)."