Aims and Principles

Biomechanics is a discipline that approaches the study of the body as though it were solely a mechanical system: all parts of the body are likened to mechanical structures and are studied as such. The following analogies may, for example, be drawn:

- bones: levers, structural members

- flesh: volumes and masses

- joints: bearing surfaces and articulations

- joint linings: lubricants

- muscles: motors, springs

- nerves: feedback control mechanisms

- organs: power supplies

- tendons: ropes

- tissue: springs

- body cavities: balloons.

The main aim of biomechanics is to study the way the body produces force and generates movement. The discipline relies primarily on anatomy, mathematics and physics; related disciplines are anthropometry (the study of human body measurements), work physiology and kinesiology (the study of the principles of mechanics and anatomy in relation to human movement).

In considering the occupational health of the worker, biomechanics helps to understand why some tasks cause injury and ill health. Some relevant types of adverse health effect are muscle strain, joint problems, back problems and fatigue.

Back strains and sprains and more serious problems involving the intervertebral discs are common examples of workplace injuries that can be avoided. These often occur because of a sudden particular overload, but may also reflect the exertion of excessive forces by the body over many years: problems may occur suddenly or may take time to develop. An example of a problem that develops over time is “seamstress’s finger”. A recent description describes the hands of a woman who, after 28 years of work in a clothing factory, as well as sewing in her spare time, developed hardened thickened skin and an inability to flex her fingers (Poole 1993). (Specifically, she suffered from a flexion deformity of the right index finger, prominent Heberden’s nodes on the index finger and thumb of the right hand, and a prominent callosity on the right middle finger due to constant friction from the scissors.) X-ray films of her hands showed severe degenerative changes in the outermost joints of her right index and middle fingers, with loss of joint space, articular sclerosis (hardening of tissue), osteophytes (bony growths at the joint) and bone cysts.

Inspection at the workplace showed that these problems were due to repeated hyperextension (bending up) of the outermost finger joint. Mechanical overload and restriction in blood flow (visible as a whitening of the finger) would be maximal across these joints. These problems developed in response to repeated muscle exertion in a site other than the muscle.

Biomechanics helps to suggest ways of designing tasks to avoid these types of injuries or of improving poorly designed tasks. Remedies for these particular problems are to redesign the scissors and to alter the sewing tasks to remove the need for the actions performed.

Two important principles of biomechanics are:

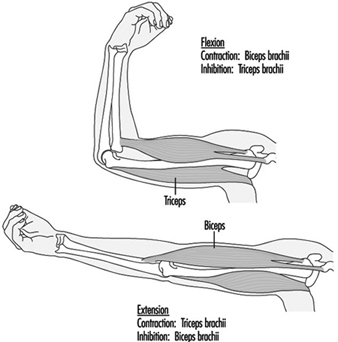

- Muscles come in pairs. Muscles can only contract, so for any joint there must be one muscle (or muscle group) to move it one way and a corresponding muscle (or muscle group) to move it in the opposite direction. Figure 1 illustrates the point for the elbow joint.

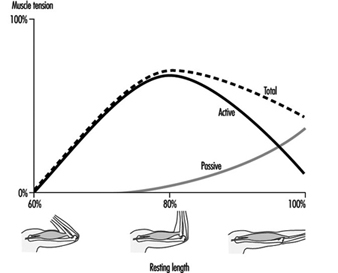

- Muscles contract most efficiently when the muscle pair is in relaxed balance. The muscle acts most efficiently when it is in the midrange of the joint it flexes. This is so for two reasons: first, if the muscle tries to contract when it is shortened, it will pull against the elongated opposing muscle. Because the latter is stretched, it will apply an elastic counterforce that the contracting muscle must overcome. Figure 2 shows the way in which muscle force varies with muscle length.

Figure 1. Skeletal muscles occur in pairs in order to initiate or reverse a movement

Figure 2. Muscle tension varies with muscle length

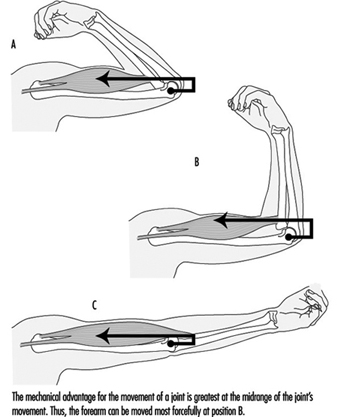

Second, if the muscle tries to contract at other than the midrange of the movement of the joint, it will operate at a mechanical disadvantage. Figure 3 illustrates the change in mechanical advantage for the elbow in three different positions.

Figure 3. Optimal positions for joint movement

An important criterion for work design follows from these principles: Work should be arranged so that it occurs with the opposing muscles of each joint in relaxed balance. For most joints, this means that the joint should be at about its midrange of movement.

This rule also means that muscle tension will be at a minimum while a task is performed. One example of the infringement of the rule is the overuse syndrome (RSI, or repetitive strain injury) which affects the muscles of the top of the forearm in keyboard operators who habitually operate with the wrist flexed up. Often this habit is forced on the operator by the design of the keyboard and workstation.

Applications

The following are some examples illustrating the application of biomechanics.

The optimum diameter of tool handles

The diameter of a handle affects the force that the muscles of the hand can apply to a tool. Research has shown that the optimum handle diameter depends on the use to which the tool is put. For exerting thrust along the line of the handle, the best diameter is one that allows the fingers and thumb to assume a slightly overlapping grip. This is about 40 mm. To exert torque, a diameter of about 50-65 mm is optimal. (Unfortunately, for both purposes most handles are smaller than these values.)

The use of pliers

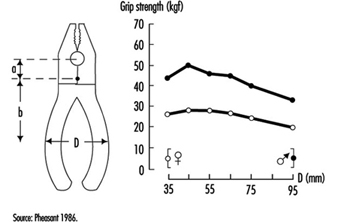

As a special case of a handle, the ability to exert force with pliers depends on the handle separation, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. Grip strength of pliers jaws exerted by male and female users as a function of handle separation

Seated posture

Electromyography is a technique that can be used to measure muscle tension. In a study of the tension in the erector spinae muscles (of the back) of seated subjects, it was found that leaning back (with the backrest inclined) reduced the tension in these muscles. The effect can be explained because the backrest takes more of the weight of the upper body.

X-ray studies of subjects in a variety of postures showed that the position of relaxed balance of the muscles that open and close the hip joint corresponds to a hip angle of about 135º. This is close to the position (128º) naturally adopted by this joint in weightless conditions (in space). In the seated posture, with an angle of 90º at the hip, the hamstring muscles that run over both the knee and hip joints tend to pull the sacrum (the part of the vertebral column that connects with the pelvis) into a vertical position. The effect is to remove the natural lordosis (curvature) of the lumbar spine; chairs should have appropriate backrests to correct for this effort.

Screwdriving

Why are screws inserted clockwise? The practice probably arose in unconscious recognition that the muscles that rotate the right arm clockwise (most people are right-handed) are larger (and therefore more powerful) that the muscles that rotate it anticlockwise.

Note that left-handed people will be at a disadvantage when inserting screws by hand. About 9% of the population are left-handed and will therefore require special tools in some situations: scissors and can openers are two such examples.

A study of people using screwdrivers in an assembly task revealed a more subtle relation between a particular movement and a particular health problem. It was found that the greater the elbow angle (the straighter the arm), the more people had inflammation at the elbow. The reason for this effect is that the muscle that rotates the forearm (the biceps) also pulls the head of the radius (lower arm bone) onto the capitulum (rounded head) of the humerus (upper arm bone). The increased force at the higher elbow angle caused greater frictional force at the elbow, with consequent heating of the joint, leading to the inflammation. At the higher angle, the muscle also had to pull with greater force to effect the screwing action, so a greater force was applied than would have been required with the elbow at about 90º. The solution was to move the task closer to the operators to reduce the elbow angle to about 90º.

The cases above demonstrate that a proper understanding of anatomy is required for the application of biomechanics in the workplace. Designers of tasks may need to consult experts in functional anatomy to anticipate the types of problems discussed. (The Pocket Ergonomist (Brown and Mitchell 1986) based on electromyographical research, suggests many ways of reducing physical discomfort at work.)

Manual Material Handling

The term manual handling includes lifting, lowering, pushing, pulling, carrying, moving, holding and restraining, and encompasses a large part of the activities of working life.

Biomechanics has obvious direct relevance to manual handling work, since muscles must move to carry out tasks. The question is: how much physical work can people be reasonably expected to do? The answer depends on the circumstances; there are really three questions that need to be asked. Each one has an answer that is based on scientifically researched criteria:

- How much can be handled without damage to the body (in the form, for example, of muscle strain, disc injury or joint problems)? This is called the biomechanical criterion.

- How much can be handled without overexerting the lungs (breathing hard to the point of panting)? This is called the physiological criterion.

- How much do people feel able to handle comfortably? This is called the psychophysical criterion.

There is a need for these three different criteria because there are three broadly different reactions that can occur to lifting tasks: if the work goes on all day, the concern will be how the person feels about the task—the psychophysical criterion; if the force to be applied is large, the concern would be that muscles and joints are not overloaded to the point of damage—the biomechanical criterion; and if the rate of work is too great, then it may well exceed the physiological criterion, or the aerobic capacity of the person.

Many factors determine the extent of the load placed on the body by a manual handling task. All of them suggest opportunities for control.

Posture and Movements

If the task requires a person to twist or reach forward with a load, the risk of injury is greater. The workstation can often be redesigned to prevent these actions. More back injuries occur when the lift begins at ground level compared to mid-thigh level, and this suggests simple control measures. (This applies to high lifting as well.)

The load.

The load itself may influence handling because of its weight and its location. Other factors, such as its shape, its stability, its size and its slipperiness may all affect the ease of a handling task.

Organization and environment.

The way work is organized, both physically and over time (temporally), also influences handling. It is better to spread the burden of unloading a truck in a delivery bay over several people for an hour rather than to ask one worker to spend all day on the task. The environment influences handling—poor light, cluttered or uneven floors and poor housekeeping may all cause a person to stumble.

Personal factors.

Personal handling skills, the age of the person and the clothing worn also can influence handling requirements. Education for training and lifting are required both to provide necessary information and to allow time for the development of the physical skills of handling. Younger people are more at risk; on the other hand, older people have less strength and less physiological capacity. Tight clothing can increase the muscle force required in a task as people strain against the tight cloth; classic examples are the nurse’s smock uniform and tight overalls when people do work above their heads.

Recommended Weight Limits

The points mentioned above indicate that it is impossible to state a weight that will be “safe” in all circumstances. (Weight limits have tended to vary from country to country in an arbitrary manner. Indian dockers, for example, were once “allowed” to lift 110 kg, while their counterparts in the former People’s Democratic Republic of Germany were “limited” to 32 kg.) Weight limits have also tended to be too great. The 55 kg suggested in many countries is now thought to be far too great on the basis of recent scientific evidence. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in the United States has adopted 23 kg as a load limit in 1991 (Waters et al. 1993).

Each lifting task needs to be assessed on its own merits. A useful approach to determining a weight limit for a lifting task is the equation developed by NIOSH:

RWL = LC x HM x VM x DM x AM x CM x FM

Where

RWL = recommended weight limit for the task in question

HM = the horizontal distance from the centre of gravity of the load to the midpoint between the ankles (minimum 15 cm, maximum 80 cm)

VM = the vertical distance between the centre of gravity of the load and the floor at the start of the lift (maximum 175 cm)

DM = the vertical travel of the lift (minimum 25 cm, maximum 200 cm)

AM = asymmetry factor–the angle the task deviates from straight out in front of the body

CM = coupling multiplier–the ability to get a good grip on the item to be lifted, which is found in a reference table

FM = frequency multipliers–the frequency of the lifting.

All variables of length in the equation are expressed in units of centimetres. It should be noted that 23 kg is the maximum weight that NIOSH recommends for lifting. This has been reduced from 40 kg after observation of many people doing many lifting tasks has revealed that the average distance from the body of the start of the lift is 25 cm, not the 15 cm assumed in an earlier version of the equation (NIOSH 1981).

Lifting index.

By comparing the weight to be lifted in the task and the RWL, a lifting index (LI) can be obtained according to the relationship:

LI=(weight to be handled)/RWL.

Therefore, particularly valuable use of the NIOSH equation is the placing of lifting tasks in order of severity, using the lifting index to set priorities for action. (The equation has a number of limitations, however, that need to be understood for its most effective application. See Waters et al. 1993).

Estimating Spinal Compression Imposed by the Task

Computer software is available to estimate the spinal compression produced by a manual handling task. The 2D and 3D Static Strength Prediction Programs from the University of Michigan (“Backsoft”) estimate spinal compression. The inputs required to the program are:

- the posture in which the handling activity is performed

- the force exerted

- the direction of the force exertion

- the number of hands exerting the force

- the percentile of the population under study.

The 2D and 3D programs differ in that the 3D software allows computations applying to postures in three dimensions. The program output gives spinal compression data and lists the percentage of the population selected that would be able to do the particular task without exceeding suggested limits for six joints: ankle, knee, hip, first lumbar disc-sacrum, shoulder, and elbow. This method also has a number of limitations that need to be fully understood in order to derive maximum value out of the program.