Fatigue and recovery are periodic processes in every living organism. Fatigue can be described as a state which is characterized by a feeling of tiredness combined with a reduction or undesired variation in the performance of the activity (Rohmert 1973).

Not all the functions of the human organism become tired as a result of use. Even when asleep, for example, we breathe and our heart is pumping without pause. Obviously, the basic functions of breathing and heart activity are possible throughout life without fatigue and without pauses for recovery.

On the other hand, we find after fairly prolonged heavy work that there is a reduction in capacity—which we call fatigue. This does not apply to muscular activity alone. The sensory organs or the nerve centres also become tired. It is, however, the aim of every cell to balance out the capacity lost by its activity, a process which we call recovery.

Stress, Strain, Fatigue and Recovery

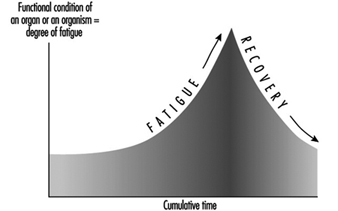

The concepts of fatigue and recovery at human work is closely related to the ergonomic concepts of stress and strain (Rohmert 1984) (figure 1).

Figure 1. Stress, strain and fatigue

Stress means the sum of all parameters of work in the working system influencing people at work, which are perceived or sensed mainly over the receptor system or which put demands on the effector system. The parameters of stress result from the work task (muscular work, non-muscular work—task-oriented dimensions and factors) and from the physical, chemical and social conditions under which the work has to be done (noise, climate, illumination, vibration, shift work, etc.—situation-oriented dimensions and factors).

The intensity/difficulty, the duration and the composition (i.e., the simultaneous and successive distribution of these specific demands) of the stress factors results in combined stress, which all the exogenous effects of a working system exert on the working person. This combined stress can be actively coped with or passively put up with, specifically depending on the behaviour of the working person. The active case will involve activities directed towards the efficiency of the working system, while the passive case will induce reactions (voluntary or involuntary), which are mainly concerned with minimizing stress. The relation between the stress and activity is decisively influenced by the individual characteristics and needs of the working person. The main factors of influence are those that determine performance and are related to motivation and concentration and those related to disposition, which can be referred to as abilities and skills.

The stresses relevant to behaviour, which are manifest in certain activities, cause individually different strains. The strains can be indicated by the reaction of physiological or biochemical indicators (e.g., raising the heart rate) or it can be perceived. Thus, the strains are susceptible to “psycho-physical scaling”, which estimates the strain as experienced by the working person. In a behavioural approach, the existence of strain can also be derived from an activity analysis. The intensity with which indicators of strain (physiological-biochemical, behaviouristic or psycho-physical) react depends on the intensity, duration, and combination of stress factors as well as on the individual characteristics, abilities, skills, and needs of the working person.

Despite constant stresses the indicators derived from the fields of activity, performance and strain may vary over time (temporal effect). Such temporal variations are to be interpreted as processes of adaptation by the organic systems. The positive effects cause a reduction of strain/improvement of activity or performance (e.g., through training). In the negative case, however, they will result in increased strain/reduced activity or performance (e.g., fatigue, monotony).

The positive effects may come into action if the available abilities and skills are improved in the working process itself, e.g., when the threshold of training stimulation is slightly exceeded. The negative effects are likely to appear if so-called endurance limits (Rohmert 1984) are exceeded in the course of the working process. This fatigue leads to a reduction of physiological and psychological functions, which can be compensated by recovery.

To restore the original performance rest allowances or at least periods with less stress are necessary (Luczak 1993).

When the process of adaptation is carried beyond defined thresholds, the employed organic system may be damaged so as to cause a partial or total deficiency of its functions. An irreversible reduction of functions may appear when stress is far too high (acute damage) or when recovery is impossible for a longer time (chronic damage). A typical example of such damage is noise-induced hearing loss.

Models of Fatigue

Fatigue can be many-sided, depending on the form and combi-nation of strain, and a general definition of it is yet not possible. The biological proceedings of fatigue are in general not measurable in a direct way, so that the definitions are mainly oriented towards the fatigue symptoms. These fatigue symptoms can be divided, for example, into the following three categories.

- Physiological symptoms: fatigue is interpreted as a decrease of functions of organs or of the whole organism. It results in physiological reactions, e.g., in an increase of heart rate frequency or electrical muscle activity (Laurig 1970).

- Behavioural symptoms: fatigue is interpreted mainly as a decrease of performance parameters. Examples are increasing errors when solving certain tasks, or an increasing variability of performance.

- Psycho-physical symptoms: fatigue is interpreted as an increase of the feeling of exertion and deterioration of sensation, depending on the intensity, duration and composition of stress factors.

In the process of fatigue all three of these symptoms may play a role, but they may appear at different points in time.

Physiological reactions in organic systems, particularly those involved in the work, may appear first. Later on, the feelings of exertion may be affected. Changes in performance are manifested generally in a decreasing regularity of work or in an increasing quantity of errors, although the mean of the performance may not yet be affected. On the contrary, with appropriate motivation, the working person may even try to maintain performance through will-power. The next step may be a clear reduction of performance ending with a breakdown of performance. The physiological symptoms may lead to a breakdown of the organism including changes of the structure of personality and in exhaustion. The process of fatigue is explained in the theory of successive destabilization (Luczak 1983).

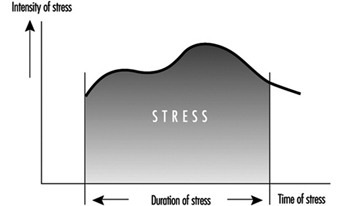

The principal trend of fatigue and recovery is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Principal trend of fatigue and recovery

Prognosis of Fatigue and Recovery

In the field of ergonomics there is a special interest in predicting fatigue dependent on the intensity, duration and composition of stress factors and to determine the necessary recovery time. Table 1 shows those different activity levels and consideration periods and possible reasons of fatigue and different possibilities of recovery.

Table 1. Fatigue and recovery dependent on activity levels

|

Level of activity |

Period |

Fatigue from |

Recovery by |

|

Work life |

Decades |

Overexertion for |

Retirement |

|

Phases of work life |

Years |

Overexertion for |

Holidays |

|

Sequences of |

Months/weeks |

Unfavourable shift |

Weekend, free |

|

One work shift |

One day |

Stress above |

Free time, rest |

|

Tasks |

Hours |

Stress above |

Rest period |

|

Part of a task |

Minutes |

Stress above |

Change of stress |

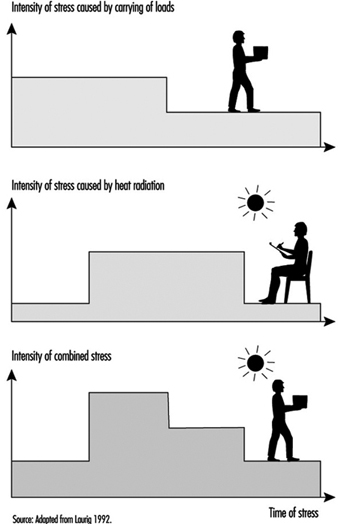

In ergonomic analysis of stress and fatigue for determining the necessary recovery time, considering the period of one working day is the most important. The methods of such analyses start with the determination of the different stress factors as a function of time (Laurig 1992) (figure 3).

Figure 3. Stress as a function of time

The stress factors are determined from the specific work content and from the conditions of work. Work content could be the production of force (e.g., when handling loads), the coordination of motor and sensory functions (e.g., when assembling or crane operating), the conversion of information into reaction (e.g., when controlling), the transformations from input to output information (e.g., when programming, translating) and the production of information (e.g., when designing, problem solving). The conditions of work include physical (e.g., noise, vibration, heat), chemical (chemical agents) and social (e.g., colleagues, shift work) aspects.

In the easiest case there will be a single important stress factor while the others can be neglected. In those cases, especially when the stress factors results from muscular work, it is often possible to calculate the necessary rest allowances, because the basic concepts are known.

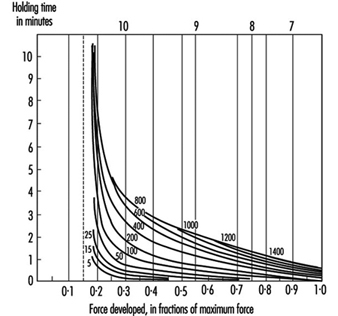

For example, the sufficient rest allowance in static muscle work depends on the force and duration of muscular contraction as in an exponential function linked by multiplication according to the formula:

![]()

with

R.A. = Rest allowance in percentage of t

t = duration of contraction (working period) in minutes

T = maximal possible duration of contraction in minutes

f = the force needed for the static force and

F = maximal force.

The connection between force, holding time and rest allowances is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. Percentage rest allowances for various combinations of holding forces and time

Similar laws exist for heavy dynamic muscular work (Rohmert 1962), active light muscular work (Laurig 1974) or different industrial muscular work (Schmidtke 1971). More rarely you find comparable laws for non-physical work, e.g., for computing (Schmidtke 1965). An overview of existing methods for determining rest allowances for mainly isolated muscle and non-muscle work is given by Laurig (1981) and Luczak (1982).

More difficult is the situation where a combination of different stress factors exists, as shown in figure 5, which affect the working person simultaneously (Laurig 1992).

Figure 5. The combination of two stress factors

The combination of two stress factors, for example, can lead to different strain reactions depending on the laws of combination. The combined effect of different stress factors can be indifferent, compensatory or cumulative.

In the case of indifferent combination laws, the different stress factors have an effect on different subsystems of the organism. Each of these subsystems can compensate for the strain without the strain being fed into a common subsystem. The overall strain depends on the highest stress factor, and thus laws of superposition are not needed.

A compensatory effect is given when the combination of different stress factors leads to a lower strain than does each stress factor alone. The combination of muscular work and low temperatures can reduce the overall strain, because low temperatures allow the body to lose heat which is produced by the muscular work.

A cumulative effect arises if several stress factors are superimposed, that is, they must pass through one physiological “bottleneck”. An example is the combination of muscular work and heat stress. Both stress factors affect the circulatory system as a common bottleneck with resultant cumulative strain.

Possible combination effects between muscle work and physical conditions are described in Bruder (1993) (see table 2).

Table 2. Rules of combination effects of two stress factors on strain

|

Cold |

Vibration |

Illumination |

Noise |

|

|

Heavy dynamic work |

– |

+ |

0 |

0 |

|

Active light muscle work |

+ |

+ |

0 |

0 |

|

Static muscle work |

+ |

+ |

0 |

0 |

0 indifferent effect; + cumulative effect; – compensatory effect.

Source: Adapted from Bruder 1993.

For the case of the combination of more than two stress factors, which is the normal situation in practice, only limited scientific knowledge is available. The same applies for the successive combination of stress factors, (i.e., the strain effect of different stress factors which affect the worker successively). For such cases, in practice, the necessary recovery time is determined by measuring physiological or psychological parameters and using them as integrating values.