Sources of meat slaughtered for human consumption include cattle, hogs, sheep, lambs and, in some countries, horses and camels. The size and production of slaughterhouses vary considerably. Except for very small operations located in rural areas, animals are slaughtered and processed in factory-type workplaces. These workplaces are usually subject to food-safety controls by the local government to prevent bacterial contamination that can cause foodborne illnesses in consumers. Examples of known pathogens in meat include salmonella and Escherichia coli. In these meat processing plants the work has become very specialized, with almost all the work being done on production disassembly lines where the meat moves on chains and conveyors, and each worker does only one operation. Almost all the cutting and processing is still done by workers. Production jobs can require between 10,000 and 20,000 cuts a day. In some large plants in the United States, for example, a few jobs, such as carcass splitting and bacon slicing, have been automated.

Slaughtering Process

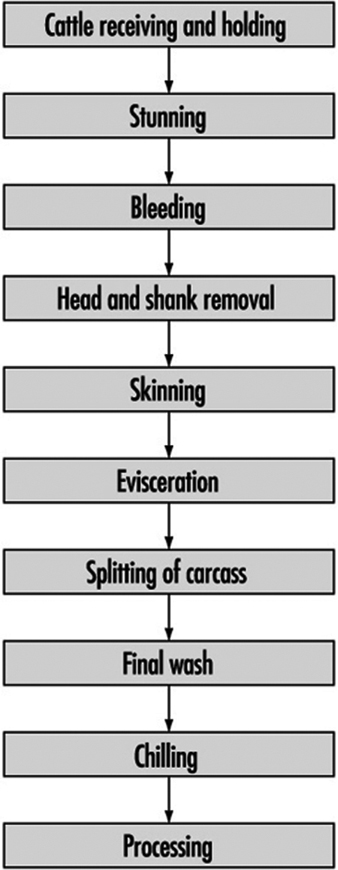

The animals are herded through a holding pen to slaughter (see figure 1). The animal must be stunned before being bled, unless slaughtered in accordance with Jewish or Muslim rites. Usually the animal is either knocked to an unconscious state with a bolt stunner gun or with a stunner gun utilizing compressed air that drives a pin into the head (the medulla oblongata) of the animal. After the stunning or “knocking” process, one of the animal’s hind legs is secured by a chain hooked onto an overhead conveyor which transfers the animal to the next room, where it is bled by “sticking” the jugular arteries in the neck with a sharp knife. The bleeding-out process follows, and the blood is drained through pipes for processing on floors below.

Figure 1. Beef slaughtering flow chart

The skin (hide) is removed by a series of cuts with knives (new air-powered knives are being used in the larger plants for some hide-removal operations) and the animal is then suspended by both hind legs from the overhead conveyor system. In some hog operations, the skin is not removed at this stage. Rather the hair is removed by sending the carcass through tanks of water heated to 58 ºC and then through a dehair machine that rubs the hair off the skin. Any remaining hair is removed by singeing and finally shaving.

The front legs and then the viscera (intestines) are removed. The head is then cut and dropped, and the carcass is split in half vertically along the spinal column. Hydraulic band saws are the usual tool for this job. After the carcass is split, it is rinsed with hot water, and may be steam vacuumed or even treated with a newly developed pasteurization process being introduced in some countries.

Government health inspectors usually inspect after the head removal, the viscera removal and the carcass splitting and final wash.

After this, the carcass, still hanging from the overhead conveyor system, moves to a cooler for chilling over the next 24 to 36 hours. The temperature is usually about 2 ºC to slow bacterial growth and inhibit spoilage.

Processing

Once chilled, the carcass halves are then cut into front and hind quarters. After this, pieces are further divided into prime cuts, depending on customer specifications. Some quarters are processed for delivery as the front or hind quarters without any further significant trimming. These pieces can weigh from 70 to 125 kg. Many plants (in the United States, the majority of plants) conduct further processing of the meat (some plants do only this processing and receive their meat from slaughterhouses). Products from these plants are shipped in boxes weighing approximately 30 kg.

Cutting is done by hand or powered saws, depending on the cuts, usually following trimming operations to remove skin. Many plants also use large grinders for grinding hamburger and other ground meats. Further processing can involve equipment including bacon presses, ham tumblers and extruders, bacon slicers, electric meat tenderizers and smoke houses. Conveyor belts and screw augers are often used to transport product. Processing areas are also kept cool, with temperatures in the 4 °C range.

Offal meats, such as liver, hearts, sweetbreads, tongues and glands, are processed in a separate area.

Many plants also treat the hides before sending them to a tanner.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Meatpacking has one of the highest rates of injury of all industries. A worker may be injured by the moving animals as they are led through the holding pen into the plant. Adequate training must be given to workers on handling live animals, and minimal worker exposure in this process is advised. Stunner guns may prematurely or inadvertently discharge while workers try to still the animals. Falling animals and nervous system reactions in stunned cattle that cause jerking present hazards to workers in the area. Further, many operations utilize a series of hooks, chains and conveyor tram rails to move the product between processing steps, posing the hazard of falling carcasses and product.

Adequate maintenance of all equipment is necessary, especially equipment used to move meat. Such equipment must be checked frequently and repaired as needed. Adequate safeguards for knocking guns, such as safety switches and making sure there is no blow back, must be taken. Workers involved in knocking and sticking operations must be trained on the hazards of this job, as well as provided with guarded knives and protective equipment to prevent injury. For sticking operations this includes arm guards, mesh gloves and special guarded knives.

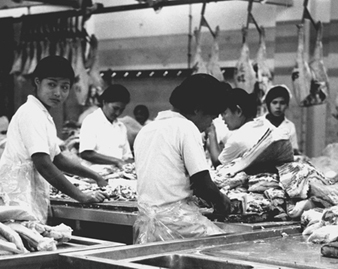

Both in the slaughter and further processing of animals, hand knives and mechanical cutting devices are used. Mechanical cutting devices include head splitters, bone splitters, snout pullers, electric band and circular saws, electric- or air-powered circular-blade knives, grinding machines and bacon processors. These types of operations have a high rate of injury, from knife cuts to amputations, because of the speed at which workers operate, the inherent danger of the tools being used and the often slippery nature of the product from fat and wet processes. Workers can be cut by their own knives and by other workers’ knives during the butchering process (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Cutting and sorting meat without protective equipment in a Thai meat packing factory

The above operations require protective equipment, including protective helmets, footwear, mesh gloves and aprons, wrist and forearm guards and waterproof aprons. Protective goggles may be required during boning, trimming and cutting operations to prevent foreign objects from entering workers’ eyes. Metal mesh gloves must not be used while operating any type of powered or electrical saw. Powered saws and tools must have proper safety guards, such as blade guards and shut-off switches. Unguarded sprockets and chains, conveyor belts and other equipment can pose a hazard. All such equipment must be properly guarded. Hand knives should also have guards to prevent the hand holding the knife from slipping over the blade. Training and adequate spacing between workers is necessary to conduct operations safely.

Workers maintaining, cleaning or unjamming equipment such as conveyor belts, bacon processors, meat grinders and other processing equipment are subject to the hazard of the inadvertent start-up of equipment. This has caused fatalities and amputations. Some equipment is cleaned while running, subjecting workers to the hazard of getting caught in the machinery.

Workers must be trained in safety lockout/tagout procedures. Implementation of procedures that prevent workers from fixing, cleaning or unjamming equipment until the equipment is off and locked out will prevent injuries. Workers involved in locking out pieces of equipment must be trained on procedures for neutralizing all energy sources.

Wet and treacherously slippery floors and stairs throughout the plant pose a serious hazard to workers. Elevated work platforms also pose a falling hazard. Workers must be provided with safety shoes with non-slip soles. Non-slip floor surfaces and roughened floors, approved by local health agencies, are available and should be used on floors and stairways. Adequate drainage in wet areas must be provided, along with proper and adequate housekeeping of floors during production hours to minimize wet and slippery surfaces. All elevated surfaces must also be properly equipped with guard rails both to prevent workers from accidental falls and to prevent worker contact and materials falling from conveyors. Toe boards should also be used on elevated platforms, where necessary. Guardrails should also be used on stairways on the production floor to prevent slipping.

The combination of wet working conditions and elaborate electrical wiring poses a hazard of electrocution to workers. All equipment must be properly grounded. Electrical outlet boxes should be provided with covers which effectively protect against accidental contact. All electrical wiring should be checked periodically for cracking, fraying or other defects, and all electrical equipment should be grounded. Ground fault circuit interrupters should be used where possible.

Lugging of carcasses (which can weigh up to 140 kg) and repetitive lifting of 30 kg boxes of meat ready for shipping can cause back injuries. Cumulative trauma disorders such as carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis and tenosynovitis are widespread in the industry. In the United States, for example, meatpacking operations have higher rates of these disorders than any other industry. The wrist, elbow and shoulder are all affected. These disorders can arise from the highly repetitive and forceful nature of the assembly line work in the plants, the use of vibrating equipment in some jobs, the use of dull knives, the cutting of frozen meat and the use of high-pressure hoses in cleaning operations. Prevention of these disorders comes through ergonomic redesign of equipment, use of mechanical assists, vigilant maintenance of vibrating equipment to minimize vibration, and improved worker training and medical programmes. Ergonomic redesign measures include:

- lowering overhead conveyors to reduce repetitive overhead throws on production lines (see figure 3)

- moving horizontal platforms that allow workers to split animals with a minimum of reaches

- providing sharp knives with redesigned handles

- building mechanical assists that reduce the force of a job (see figure 4)

- increased staffing on high-force jobs, assuring properly sized hand tools and gloves and careful design of packing areas to minimize twisting when lifting, as well as to minimize lifting from below the knees and above the shoulders

- vacuum hoists and other mechanical lifting devices to reduce lifting of boxes (see figure 5).

Figure 3. With conveyer belts located beneath worktables, workers can push finished products through a hole in the table instead of having to throw meat over their heads

United Food & Commercial Workers, AFL-CIO

Figure 4. Having paddle bones pulled out by the force of an attached chain rather than manually lessens musculoskeletal hazards

United Food & Commercial Workers, AFL-CIO

Figure 5. The use of vacuum hoists for lifting boxes allows workers to guide boxes rather than load them by hand

United Food & Commercial Workers, AFL-CIO

Aisles and walkways should be dry and free of obstacles so that carrying and transporting heavy loads can be done safely.

Workers should be trained or proper use of knives. Cutting frozen meat should be avoided completely.

Early medical intervention and treatment for symptomatic workers is also desirable. Because of the similar nature of the stressors on jobs in this industry, job rotation must be used with caution. Job analyses must be carried out and reviewed to assure that the same muscle tendon groups are not used in different tasks. In addition, workers must be adequately trained in all jobs in any planned rotation.

Machines and equipment found in meatpacking plants produce a high level of noise. Workers must be provided with ear plugs, as well as hearing examinations to ascertain any potential hearing loss. Further, sound-dampening equipment should be used on machinery where possible. Good maintenance on conveyor systems can prevent unnecessary noise.

Workers can be exposed to toxic chemicals during the cleaning and sanitizing of equipment. Compounds used include both alkaline (caustic) and acid cleaners. These can cause dryness, allergic rashes and other skin problems. Liquids can splash up and burn the eyes. Depending on the type of cleaning compound used, PPE—including eye, face and arm coverings, aprons and protective footwear—must be provided. Hand and eye washing facilities should also be available. High-pressure hoses used to transport hot water for disinfecting equipment can also cause burns. Adequate worker training on the use of such hoses is important. Chlorine in the water used to wash the carcasses can also cause eye, throat and skin irritation. New anti-bacterial rinses are being introduced on the slaughter side to decrease bacteria that can cause foodborne illnesses. Adequate ventilation must be provided. Special care to assure that the strength of the chemicals does not exceed manufacturers’ instructions must be taken.

Ammonia is used as a refrigerant in the industry, and ammonia leaks from pipes are common. Ammonia gas is irritating to the eyes and skin. Mild to moderate exposure to the gas can produce headaches, burning in the throat, perspiration, nausea and vomiting. If escape is not possible, there may be severe irritation of the respiratory tract, producing cough, pulmonary oedema or respiratory arrest. Adequate maintenance of refrigeration lines is key to preventing such leaks. In addition, once an ammonia leak is detected, monitoring and evacuation procedures must be carried out to prevent dangerous exposures.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) in the form of dry ice is used in the packaging area. During this process, CO2 gas may escape from these vats and spread throughout the room. Exposure can cause headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting and, at high levels, death. Adequate ventilation must be provided.

Blood tanks present hazards associated with confined spaces if the plant does not utilize a closed piping and processing system for the blood. Toxic substances emitted from decomposing blood and lack of oxygen pose serious hazards to those having to enter and/or clean tanks or work in the area. Prior to entry, the atmosphere must be tested for toxic chemicals, and the presence of adequate oxygen must be assured.

Workers are exposed to infectious diseases such as brucellosis, erysipeloid, leptospirosis, dermatophytoses and warts.

Brucellosis is caused by a bacterium and is transmitted by the handling of infected cattle or swine. Persons infected by this bacterium experience constant or recurring fever, headaches, weakness, joint pain, night sweats and loss of appetite. Limiting the number of infected cattle slaughtered is one key to preventing this disorder.

Erysipeloid and leptospirosis are also caused by bacteria. Erysipeloid is transmitted by infection of skin puncture wounds, scratches and abrasions; it causes redness and irritation around the site of infection and can spread to the bloodstream and lymph nodes. Leptospirosis is transmitted through direct contact with infected animals or through water, moist soil or vegetation contaminated by the urine of infected animals. Muscular aches, eye infections, fever, vomiting, chills and headaches occur, and kidney and liver damage may develop.

Dermatophytosis, on the other hand, is a fungal disease and is transmitted by contact with the hair and skin of infected persons and animals. Dermatophytosis, also know as ringworm, causes the hair to fall out and small, yellowish cuplike crusts to develop on the scalp.

Verruca vulgaris, a wart caused by a virus, can be spread by infectious workers who have contaminated towels, meat, fish knives, work tables or other objects.

Other diseases that are found in meatpacking plants in some countries include Q fever and tuberculosis. The primary carriers of Q fever are cattle, sheep, goats and ticks. Humans are usually infected by inhaling aerosolized particles from contaminated environments. Typical symptoms include fever, malaise, severe headache and muscular and abdominal pain. The incidence of toxoplasma antibodies amongst abattoir workers is high in certain countries.

Dermatitis is also common in meatpacking plants. Exposure to blood and other animal fluids, exposure to wet conditions, and exposure to cleaning compounds used for cleaning/sanitation in facilities can lead to skin irritation.

Infectious diseases and dermatitis can be prevented with personal hygiene that includes ready and easy access to sanitation and hand-washing facilities that contain soap and disposable hand towels, the provision of proper PPE (which may include protective gloves as well as eye and respiratory protection where exposure to airborne animal body fluids is possible), the use of some barrier creams to provide limited protection against irritants, worker education and early medical care.

The kill floor, where the slaughtering, bleeding and splitting of the animal is done, can be especially hot and humid. A properly working ventilation system that removes the hot, humid air and prevents heat stress should be used. Fans, preferably overhead or roof fans, increase air movement. Beverages should be provided to replace fluids and salts lost through sweating, and frequent rest breaks, in a cool area, should be allowed.

There is also a distinctive smell in slaughterhouses, due to a mixture of odours such as those of wet leather, blood, vomit, urine and faeces of animals. This smell spreads throughout the kill floor, offal, rendering and hide areas. Exhaust ventilation is necessary to remove the odours.

Refrigerated work environments are essential in the meatpacking industry. Processing and transporting meat products generally require temperatures at or below 9 °C. Areas such as freezers may require temperatures to go as low as –40 °C. The most common cold-related injuries are frostnip, frostbite, immersion foot and trenchfoot, which occur in localized areas of the body. A serious consequence of cold stress is hypothermia. The respiratory system, the circulatory system and the osteoarticular system can also be affected by overexposure to the cold.

To prevent the consequences of cold stress and reduce the hazards of cold working conditions, workers should wear appropriate clothing, and the workplace should have proper equipment, administrative controls and engineering controls. Multiple layers of clothing provide better protection than single thick garments. Cooling equipment and air distribution systems should minimize air velocity. Unit coolers should be placed as far away from workers as possible, and wind deflectors and barriers should be used to protect workers from windchill.