The motion picture and television industry is found throughout the world. Motion picture production can take place in fixed studios, on large commercial studio lots or on location anywhere. Film production companies range in size from large corporations’ own studios to small companies that rent space in commercial studios. The production of television shows, soap operas, videos and commercials has much in common with motion picture production.

Motion picture production involves many stages and a crew of interacting specialists. The planning stages include obtaining a finished script, determining the budget and schedule, choosing types of location and studios, designing the scene-by-scene appearance of the film, selecting costumes, planning sequence of action and camera locations and lighting schemes.

Once the planning is completed, the detailed process of choosing the location, building sets, gathering the props, arranging the lighting and hiring the actors, stunt performers, special effects operators and other needed support personnel begins. Filming follows the preproduction stage. The final step is film processing and editing, which is not discussed in this article.

Motion picture and television production can involve a wide variety of chemical, electrical and other hazards, many of which are unique to the film industry.

Hazards and Precautions

Filming location

Filming in a studio or on a studio lot has the advantage of permanent facilities and equipment, including ventilation systems, power, lighting, scene shops, costume shops and more control over environmental conditions. Studios can be very large in order to accommodate a variety of filming situations.

Filming on location, especially outdoors in remote locations, is more difficult and hazardous than in a studio because transportation, communications, power, food, water, medical services, living quarters and so on must be provided. Filming on location can expose the film crew and actors to a wide variety of hazardous conditions, including wild animals, poisonous reptiles and plants, civil unrest, climate extremes and adverse local weather conditions, communicable diseases, contaminated food and water, structurally unsafe buildings, and buildings contaminated with asbestos, lead, biological hazards and so on. Filming on water, in the mountains, in deserts and other dangerous locales poses obvious hazards.

The initial survey of possible filming locations should involve evaluating these and other potential hazards to determine the need for special precautions or alternative locations.

Fabricating scenery for motion pictures can involve constructing or modifying a building or buildings, building of indoor and outdoor sets and so on. These can be full size or scaled down. Stages and scenery should be strong enough to bear the loads under consideration (see “Scenery shops” in this chapter).

Life safety

Basic life safety includes ensuring adequate exits, keeping access routes and exits marked and clear of equipment and electrical cables and removal or proper storage and handling of combustible materials, flammable liquids and compressed gases. Dry vegetation around outdoor locations and combustible materials used in filming such as sawdust and tents must be removed or flame-proofed.

Automobiles, boats, helicopters and other means of transportation are common on film locations and a cause of many accidents and fatalities, both when used for transportation and while filming. It is essential that all drivers of vehicles and aircraft be fully qualified and obey all relevant laws and regulations.

Scaffolding and rigging

On location and in studios, lights are rigged to sets, scaffolding or permanent overhead grids, or are free standing. Rigging is also used to fly scenery or people for special effects. Hazards include collapsing scaffolds, falling lights and other equipment and failures of rigging systems.

Precautions for scaffolds include safe construction, guardrails and toeboards, proper supporting of rolling scaffolds and securing of all equipment. Construction, operation, maintenance, inspection and repair of rigging systems should be done only by properly trained and qualified persons. Only assigned personnel should have access to work areas such as scaffolds and catwalks.

Electrical and lighting equipment

Large amounts of power are usually needed for camera lights and everyday electrical needs on a set. In the past direct current (DC) power was used, but alternating current (AC) power is common today. Often, and especially on location, independent sources of power are used. Examples of electrical hazards include shorting of electrical wiring or equipment, inadequate wiring, deteriorated wiring or equipment, inadequate grounding of equipment and working in wet locations. Tie-ins to the power sources and un-ties at the end of filming are two of the most dangerous activities.

All electrical work should be done by licensed electricians and should follow standard electrical safety practices and codes. Safer direct current should be used around water when possible, or ground fault circuit interrupters installed.

Lighting can pose both electrical and health hazards. High-voltage gas discharge lamps such as neons, metal halide lamps and carbon arc lamps are especially hazardous and can pose electrical, ultraviolet radiation and toxic fume hazards.

Lighting equipment should be kept in good condition, regularly inspected and adequately secured to prevent lights from tipping or falling. It is particularly important to check high-voltage discharge lamps for lens cracks that could leak ultraviolet radiation.

Cameras

Camera crews can film in many hazardous situations, including shooting from a helicopter, moving vehicle, camera crane or side of a mountain. Basic types of camera mountings include fixed tripods, dollies for mobile cameras, camera cranes for high shots and insert camera cars for shots of moving vehicles. There have been several fatalities among camera operators while filming under unsafe conditions or near stunts and special effects.

Basic precautions for camera cranes include testing of lift controls, ensuring a stable surface for the crane base and pedestal; properly laid tracking surfaces, ensuring safe distances from high-tension electrical wires; and body harnesses where required.

Insert camera cars that have been engineered for mounting of cameras and towing of the vehicle to be filmed are recommended instead of mounting cameras on the outside of the vehicle being filmed. Special precautions include having a safety checklist, limiting the number of personnel on the car, rigging done by experts, abort procedures and having a dedicated radio communications procedure.

Actors, extras and stand-ins

See the article “Actors” in this chapter.

Costumes

Costumes are made and cared for by wardrobe attendants, who may be exposed to a wide variety of dyes and paints, hazardous solvents, aerosol sprays and so on, often without ventilation.

Hazardous chlorinated cleaning solvents should be replaced with safer solvents such as mineral spirits. Adequate local exhaust ventilation should be used when spraying dyes or using solvent-containing materials. Mixing of powders should be done in an enclosed glove box.

Special effects

A wide variety of special effects are used in motion picture production to simulate real events that would otherwise be too dangerous, impractical or expensive to execute. These include fogs, smoke, fire, pyrotechnics, firearms, snow, rain, wind, computer-generated effects and miniature or scaled-down sets. Many of these have significant hazards. Other hazardous special effects can involve the use of lasers, toxic chemicals such as mercury to give silvery effects, flying objects or people with rigging and electric hazards associated with rain and other water effects. Appropriate precautions would need to be taken with such special effects.

General precautions for hazardous special effects include adequate preplanning, having written safety procedures, using adequately trained and experienced operators and the least hazardous special effects possible, coordinating with the fire department and other emergency services, making everyone aware of the intended use of special effects (and being able to refuse to participate), not allowing children in the vicinity, running detailed rehearsals with testing of the effects, clearing the set of all but essential personnel, having a dedicated emergency communications system, minimizing the number of retakes and having procedures ready to abort production.

Pyrotechnics are used to create effects involving explosions, fires, light, smoke and sound concussions. Pyrotechnics materials are usually low explosives (mostly Class B), including flash powder, flash paper, gun cotton, black powder and smokeless powder. They are used in bullet hits (squibs), blank cartridges, flash pots, fuses, mortars, smoke pots and many more. Class A high explosives, such as dynamite, should not be used, although detonating cord is sometimes used. The major problems associated with pyrotechnics include premature triggering of the pyrotechnic effect; causing a fire by using larger quantities than needed; lack of adequate fire extinguishing capabilities; and having inadequately trained and experienced pyrotechnics operators.

In addition to the general precautions, special precautions for explosives used in pyrotechnics include proper storage, the use of appropriate type and in smallest amounts necessary to achieve the effect, and testing them in the absence of spectators. When pyrotechnics are used smoking should be banned and firefighting equipment and trained personnel should be on hand. The materials should be set off by electronic firing controls and adequate ventilation is needed.

The uses of fire effects range from ordinary gas stoves and fireplaces to the destructive fires involved in burning cars, houses, forests and even people (figure 1). In some cases, fires can be simulated by flickering lights and other electronic effects. Materials used to create fire effects include propane gas burners, rubber cement, gasoline and kerosene. They are often used in conjunction with pyrotechnic special effects. Hazards are directly related to the fire getting out of control and the heat they generate. Poor maintenance of fire generating equipment and the excessive use of flammable materials or the presence of other unintended combustible materials, and improper storage of combustible and flammable liquids and gases are all risks. Inexperienced special effects operators can also be a cause of accidents as well.

Figure 1. Fire special effect

William Avery

Special precautions are similar to those needed for pyrotechnics, such as replacing gasoline, rubber cement and other flammable substances with the safer combustible gels and liquid fuels which have been developed in recent years. All materials in the fire area should be non-combustible or flame-proofed. This precaution includes flame-proofed costumes for actors in the vicinity.

Fogs and smoke effects are common in filming. Dry ice (carbon dioxide), liquid nitrogen, petroleum distillates, zinc chloride smoke generators (which might also contain chlorinated hydrocarbons), ammonium chloride, mineral oil, glycol fogs and water mists are common fog-generating substances. Some materials used, such as petroleum distillates and zinc chloride, are severe respiratory irritants and can cause chemical pneumonia. Dry ice, liquid nitrogen and water mists represent the least chemical hazards, although they can displace oxygen in enclosed areas, possibly making the air unfit for supporting life, especially in enclosed areas. Microbiological contamination can be a problem associated with water-mist generating systems. Some evidence is forthcoming that respiratory irritation is possible from those fogs and smokes that were thought to be safest, such as mineral oil and glycols.

Special precautions include eliminating the most hazardous fogs and smoke; using a fog with the machine designed for it; limiting duration of use, including limiting the number of retakes; and avoiding use in enclosed spaces. Fogs should be exhausted as soon as possible. Respiratory protection for the camera crew should be provided.

Firearms are common in films. All types of firearms are used, ranging from antique firearms to shotguns and machine guns. In many countries (not including the United States) live ammunition is banned. However, blank ammunition, which is commonly used in conjunction with live bullet hits in order to simulate actual bullet impacts, has caused many injuries and fatalities. Blank ammunition used to consist of a metal casing with a percussion primer and smokeless powder topped with a paper wad, which could be ejected at high velocity when fired. Some modern safety blanks use special plastic inserts with a primer and flash powder, giving only a flash and noise. Blank ammunition is commonly used in conjunction with bullet hits (squibs), consisting of a plastic-cased detonator imbedded in the object to be struck by the bullet to simulate actual bullet impacts. Hazards, besides the use of live ammunition, include the effects of use of blanks at close range, mixing up live and blank ammunition or using the wrong ammunition in a firearm. Improperly modified firearms can be dangerous, as can the lack of adequate training in the use of blank-firing firearms.

Live ammunition and unmodified firearms should be banned from a set and non-firing facsimile weapons used whenever possible. Firearms that can actually fire a bullet should not be used, only proper safety blanks. Firearms should be checked regularly by the property master or other firearms expert. Firearms should be locked away, as should all ammunition. Guns should never be pointed at actors in a scene, and the camera crew and others in close proximity to the set should be protected with shields from blanks fired from weapons.

Stunts

A stunt can be defined as any action sequence that involves a greater than normal risk of injury to performers or others on the set. With increasing demands for realism in films, stunts have become very common. Examples of potentially hazardous stunts include high falls, fights, helicopter scenes, car chases, fires and explosions. About half the fatalities occurring during filming are stunt-related, often also involving special effects.

Stunts can endanger not only the stunt performer but often the camera crew and other performers may be injured as well. Most of the general precautions described for special effects also apply to stunts. In addition, the stunt performer should be experienced in the type of stunt being filmed. A stunt coordinator should be in charge of all stunts since a person cannot perform a stunt and be in adequate control of safety, especially when there are several stunt performers.

Aircraft, especially helicopters, have been involved in the most serious multiple fatality accidents in motion picture production. Pilots are often not adequately qualified for stunt flying. Acrobatic manoeuvres, hovering close to the ground, flying too close to sets using pyrotechnics and filming from helicopters with open doors or from the pontoons without adequate fall protection are some of the most dangerous situations. See the article “Helicopters” elsewhere in the Encyclopaedia.

One precaution is to employ an independent aviation consultant, in addition to the pilot, to recommend and oversee safety procedures. Restriction of personnel within 50 feet of grounded aircraft and clear written procedures for filming on ground near aircraft with their engines running or during aircraft landings or takeoffs are other safety measures. Coordination with any pyrotechnics or other hazardous special effects operators is essential, as are procedures to ensure the safety of camera operators filming from aircraft. Procedures for aborting an operation are needed.

Vehicle action sequences have also been a source of many accidents and fatalities. Special effects, such as explosions, crashes, driving into rivers and car chase scenes with multiple cars, are the most common cause of accidents. Motorcycle scenes can be even more hazardous than automobiles because the operator of the motorcycle suffers from the lack of personal protection.

Special precautions include using camera cars. Using stunt drivers for all cars in a stunt scene can lower the accident rate, as can special training for non-stunt passengers. Other safety rules include proper safety equipment, inspection of all ramps and other equipment to be used during a stunt, using dummies in cars during crashes, explosions and other extremely high risk sequences and not driving cars directly towards cameras if there is a camera operator behind the camera. See figure 2 for an example of using dummies in a roller coaster stunt. Adequate ventilation is needed for automobiles that are being filmed indoors with engines running. Stunt motorcycles should be equipped with a deadman switch so that the motor shuts off when the rider separates from the motorcycle.

Figure 2. Using dummies for a roller coaster stunt.

William Avery

Stunts using fire and explosion place performers at higher risk and require special precautions beyond those used just for the special effects. Protection for stunt performers directly exposed to flames includes wearing a protective barrier gel (e.g., Zel Jel) on the hair, the skin, clothing and so on. Proper protective clothing, including fireproof suits under costumes; flame-resistant gloves and boots; and sometimes hidden oxygen tanks, should be supplied. Specially trained personnel equipped with carbon dioxide fire extinguishers should be on hand in case of an emergency.

Fight scenes can involve performers in fistfights or other unarmed combat or the use of knives, swords, firearms and other combat equipment. Many film and stage fights do not involve the use of stunt performers, thus increasing the risk of injury because of the lack of training.

Simulated weapons, such as knives and swords with retractable blades, are one safeguard. Weapons should be stored carefully. Training is key. The performer should know how to fall and how to use specific weapons. Adequate choreography and rehearsals of the fights is needed, as is proper protective clothing and equipment. A blow should never be aimed directly at an actor. If a fight involves a high degree of hazard, such as falling down a flight of stairs or crashing through a window, a professional stunt double should be used.

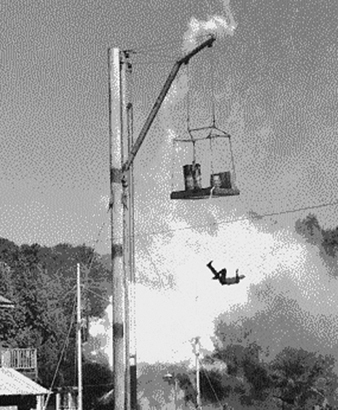

Falls in stunts can range from falling down a flight of stairs to falling off a horse, being thrown through the air by a trampoline or ratchet catapult system, or a high fall off a cliff or building (figure 3). There have been many injuries and fatalities from poorly prepared falls.

Figure 3. High fall stunt.

Only experienced stunt performers should attempt fall stunts. When possible, the fall should be simulated. For example, falling down a flight of stairs can be filmed a few stairs at a time so the stunt performer is never out of control, or a fall off a tall building simulated by a fall of a few feet onto a net and using a dummy for the rest of the fall. Precautions for high falls involve a high fall coordinator and a specialized fall/arrest system for safe deceleration. Falls of more than 15 feet require two safety spotters. Other precautions for falls include airbags, crash pads of canvas filled with sponge rubber, sand pits and so on, depending on the type of fall. Testing of all equipment is crucial.

Animal scenes are potentially very hazardous because of the unpredictability of animals. Some animals, such as large cats, can attack if startled. Large animals like horses can be a hazard just because of their size. Dangerous, untrained or unhealthy animals should not be used on sets. Venomous reptiles such as rattlesnakes are particularly hazardous. In addition to the hazards to personnel, the health and safety of the animals should be considered.

Only trained animal handlers should be allowed to work with animals. Adequate conditions for the animals are needed, as is basic animal safety equipment, such as fire extinguishers, fire hoses, nets and tranquilizing equipment. Animals should be allowed adequate time to become familiar with the set, and only required personnel should be permitted on the set. Conditions that could upset animals should be eliminated and animals kept from exposure to loud noises or light flashes whenever possible, thus ensuring the animals will not be injured and will not become unmanageable. Certain situations—for example, those using venomous reptiles or large numbers of horses—will require special precautions.

Water stunts can include diving, filming in fast-moving water, speedboat stunts and sea battles. Hazards include drowning, hypothermia in cold water, underwater obstructions and contaminated water. Emergency teams, including certified safety divers, should be on hand for all water stunts. Diver certification for all performers or camera operators using self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) and provision of standby breathing equipment are other precautions. Emergency decompression procedures for dives over 10 m should be in place. Safety pickup boats for rescue and proper safety equipment, such as use of nets and ropes in fast-moving water, are needed.

Health and Safety Programmes

Most major film studios have a full-time health and safety officer to oversee the health and safety programme. Problems of responsibility and authority can occur, however, when a studio rents facilities to a production company, as is increasingly common. Most production companies do not have a health and safety programme. A health and safety officer, with authority to establish safety procedures and to ensure they are carried out, is essential. There is a need to coordinate the activities of others charged with production planning, such as stunt coordinators, special effects operators, firearms experts and the key grip (who is usually the individual most responsible for the safety of sets, cameras, scaffolding, etc.), each of whom has specialized safety knowledge and experience. A health and safety committee that meets regularly with representatives from all departments and unions can provide a conduit between the management and employees. Many unions have an independent health and safety committee which can be a source of health and safety expertise.

Medical services

Both non-emergency and emergency medical services are essential during film production. Many film studios have a permanent medical department, but most production companies do not. The first step in determining the degree of on-location medical services to be provided is a needs assessment, to identify potential medical risks, including the need for vaccination in certain countries, possible local endemic diseases, evaluation of local environmental and climate conditions, and an evaluation of the quality of local medical resources. The second, pre-planning stage involves a detailed analysis of major risks and availability of adequate emergency and other medical care in order to determine what type of emergency planning is essential. In situations where there are high risks and/or remote locations, trained emergency physicians would be needed on location. Where there is quick access to adequate emergency facilities, paramedics or emergency medical technicians with advanced training would suffice. In addition, adequate emergency transportation should be arranged beforehand. There have been several fatalities due to the lack of adequate emergency transportation (Carlson 1989; McCann 1989).

Standards

There are few occupational safety and health regulations aimed specifically at the film production industry. However, many general regulations, such as those affecting fire safety, electrical hazards, scaffolding, lifts, welding and so on, are applicable. Local fire departments generally require special fire permits for filming and may require that standby fire personnel be present on filming sites.

Many productions have special requirements for the licensing of certain special effects operators, such as pyrotechnicians, laser operators and firearms users. There can be regulations and permits required for specific situations, such as the sale, storage and use of pyrotechnics, and the use of firearms.