Socialization

The process by which outsiders become organizational insiders is known as organizational socialization. While early research on socialization focused on indicators of adjustment such as job satisfaction and performance, recent research has emphasized the links between organizational socialization and work stress.

Socialization as a Moderator of Job Stress

Entering a new organization is an inherently stressful experience. Newcomers encounter a myriad of stressors, including role ambiguity, role conflict, work and home conflicts, politics, time pressure and work overload. These stressors can lead to distress symptoms. Studies in the 1980s, however, suggest that a properly managed socialization process has the potential for moderating the stressor-strain connection.

Two particular themes have emerged in the contemporary research on socialization:

- the acquisition of information during socialization,

- supervisory support during socialization.

Information acquired by newcomers during socialization helps alleviate the considerable uncertainty in their efforts to master their new tasks, roles and interpersonal relationships. Often, this information is provided via formal orientation-cum-socialization programmes. In the absence of formal programmes, or (where they exist) in addition to them, socialization occurs informally. Recent studies have indicated that newcomers who proactively seek out information adjust more effectively (Morrison l993). In addition, newcomers who underestimate the stressors in their new job report higher distress symptoms (Nelson and Sutton l99l).

Supervisory support during the socialization process is of special value. Newcomers who receive support from their supervisors report less stress from unmet expectations (Fisher l985) and fewer psychological symptoms of distress (Nelson and Quick l99l). Supervisory support can help newcomers cope with stressors in at least three ways. First, supervisors may provide instrumental support (such as flexible work hours) that helps alleviate a particular stressor. Secondly, they may provide emotional support that leads a newcomer to feel more efficacy in coping with a stressor. Thirdly, supervisors play an important role in helping newcomers make sense of their new environment (Louis l980). For example, they can frame situations for newcomers in a way that helps them appraise situations as threatening or nonthreatening.

In summary, socialization efforts that provide necessary information to newcomers and support from supervisors can prevent the stressful experience from becoming distressful.

Evaluating Organizational Socialization

The organizational socialization process is dynamic, interactive and communicative, and it unfolds over time. In this complexity lies the challenge of evaluating socialization efforts. Two broad approaches to measuring socialization have been proposed. One approach consists of the stage models of socialization (Feldman l976; Nelson l987). These models portray socialization as a multistage transition process with key variables at each of the stages. Another approach highlights the various socialization tactics that organizations use to help newcomers become insiders (Van Maanen and Schein l979).

With both approaches, it is contended that there are certain outcomes that mark successful socialization. These outcomes include performance, job satisfaction, organizational commit-ment, job involvement and intent to remain with the organization. If socialization is a stress moderator, then distress symptoms (specifically, low levels of distress symptoms) should be included as an indicator of successful socialization.

Health Outcomes of Socialization

Because the relationship between socialization and stress has only recently received attention, few studies have included health outcomes. The evidence indicates, however, that the socialization process is linked to distress symptoms. Newcomers who found interactions with their supervisors and other newcomers helpful reported lower levels of psychological distress symptoms such as depression and inability to concentrate (Nelson and Quick l99l). Further, newcomers with more accurate expectations of the stressors in their new jobs reported lower levels of both psychological symptoms (e.g., irritability) and physiological symptoms (e.g., nausea and headaches).

Because socialization is a stressful experience, health outcomes are appropriate variables to study. Studies are needed that focus on a broad range of health outcomes and that combine self-reports of distress symptoms with objective health measures.

Organizational Socialization as Stress Intervention

The contemporary research on organizational socialization suggests that it is a stressful process that, if not managed well, can lead to distress symptoms and other health problems. Organizations can take at least three actions to ease the transition by way of intervening to ensure positive outcomes from socialization.

First, organizations should encourage realistic expectations among newcomers of the stressors inherent in the new job. One way of accomplishing this is to provide a realistic job preview that details the most commonly experienced stressors and effective ways of coping (Wanous l992). Newcomers who have an accurate view of what they will encounter can preplan coping strategies and will experience less reality shock from those stressors about which they have been forewarned.

Secondly, organizations should make numerous sources of accurate information available to newcomers in the form of booklets, interactive information systems or hotlines (or all of these). The uncertainty of the transition into a new organization can be overwhelming, and multiple sources of informational support can aid newcomers in coping with the uncertainty of their new jobs. In addition, newcomers should be encouraged to seek out information during their socialization experiences.

Thirdly, emotional support should be explicitly planned for in designing socialization programmes. The supervisor is a key player in the provision of such support and may be most helpful by being emotionally and psychologically available to newcomers (Hirshhorn l990). Other avenues for emotional support include mentoring, activities with more senior and experienced co-workers, and contact with other newcomers.

Gravel

Gravel is a loose conglomerate of stones that have been mined from a surface deposit, dredged from a river bottom or obtained from a quarry and crushed into desired sizes. Gravel has a variety of uses, including: for rail beds; in roadways, walkways and roofs; as filler in concrete (often for foundations); in landscaping and gardening; and as a filter medium.

The principal safety and health hazards to those who work with gravel are airborne silica dust, musculoskeletal problems and noise. Free crystalline silicon dioxide occurs naturally in many rocks that are used to make gravel. The silica content of bulk species of stone varies and is not a reliable indicator of the percentage of airborne silica dust in a dust sample. Granite contains about 30% silica by weight. Limestone and marble have less free silica.

Silica can become airborne during quarrying, sawing, crushing, sizing and, to a lesser extent, spreading of gravel. Generation of airborne silica can usually be prevented with water sprays and jets, and sometimes with local exhaust ventilation (LEV). In addition to construction workers, workers exposed to silica dust from gravel include quarry workers, railroad workers and landscape workers. Silicosis is more common among quarry or stone-crushing workers than among construction workers who work with gravel as a finished product. An elevated risk of mortality from pneumoconiosis and other non-malignant respiratory disease has been observed in one cohort of workers in the crushed-stone industry in the United States.

Musculoskeletal problems can occur as a result of manual loading or unloading of gravel or during manual spreading. The larger the individual pieces of stone and the larger the shovel or other tool used, the more difficult it is to manage the material with hand tools. The risk of sprains and strains can be reduced if two or more workers work together on strenuous tasks, and more so if draught animals or powered machines are used. Smaller shovels or rakes carry or push less weight than larger ones and can reduce the risk of musculoskeletal problems.

Noise accompanies mechanical processing or handling of stone or gravel. Stone crushing using a ball mill generates considerable low-frequency noise and vibration. Transporting gravel through metal chutes and mixing it in drums are both noisy processes. Noise can be controlled by using sound-absorbing or -reflecting materials around the ball mill, by using chutes lined with wood or other sound-absorbing (and durable) material or by using noise-insulated mixing drums.

Asphalt

Asphalts can generally be defined as complex mixtures of chemical compounds of high molecular weight, predominantly asphaltenes, cyclic hydrocarbons (aromatic or naphthenic) and a lesser quantity of saturated components of low chemical reactivity. The chemical composition of asphalts depends both on the original crude oil and on the process used during refining. Asphalts are predominantly derived from crude oils, especially heavier residue crude oil. Asphalt also occurs as a natural deposit, where it is usually the residue resulting from the evaporation and oxidation of liquid petroleum. Such deposits have been found in California, China, the Russian Federation, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela. Asphalts are non-volatile at ambient temperatures and soften gradually when heated. Asphalt should not be confused with tar, which is physically and chemically dissimilar.

A wide variety of applications include paving streets, highways and airfields; making roofing, waterproofing and insulating materials; lining irrigation canals and reservoirs; and the facing of dams and levees. Asphalt is also a valuable ingredient of some paints and varnishes. It is estimated that the current annual world production of asphalts is over 60 million tonnes, with more than 80% being used in need construction and maintenance and more than 15% used in roofing materials.

Asphalt mixes for road construction are produced by first heating and drying mixtures of graded crushed stone (such as granite or limestone), sand and filler and then mixing with penetration bitumen, referred to in the US as straight-run asphalt. This is a hot process. The asphalt is also heated using propane flames during application to a road bed.

Exposures and Hazards

Exposures to particulate polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in asphalt fumes have been measured in a variety of settings. Most of the PAHs found was composed of napthalene derivatives, not the four- to six-ring compounds which are more likely to pose a significant carcinogenic risk. In refinery asphalt processing units, respirable PAH levels range from non-detectable to 40 mg/m3. During drum-filling operations, 4 hour breathing zone samples ranged from 1.0 mg/m3upwind to 5.3 mg/m3 downwind. At asphalt mixing plants, exposures to benzene-soluble organic compounds ranged from 0.2 to 5.4 mg/m3. During paving operations, exposures to respirable PAH ranged from less than 0.1 mg/m3 to 2.7 mg/m3. Potentially noteworthy worker exposures may also occur during the manufacture and application of asphalt roofing materials. Little information is available regarding exposures to asphalt fumes in other industrial situations and during the application or use of asphalt products.

Handling of hot asphalt can cause severe burns because it is sticky and is not readily removed from the skin. The principal concern from the industrial toxicological aspect is irritation of the skin and eyes by fumes of hot asphalt. These fumes may cause dermatitis and acne-like lesions as well as mild keratoses on prolonged and repeated exposure. The greenish-yellow fumes given off by boiling asphalt can also cause photosensitization and melanosis.

Although all asphaltic materials will combust if heated sufficiently, asphalt cements and oxidized asphalts will not normally burn unless their temperature is raised about 260°C. The flammability of the liquid asphalts is influenced by the volatility and amount of petroleum solvent added to the base material. Thus, the rapid-curing liquid asphalts present the greatest fire hazard, which becomes progressively lower with the medium- and slow-curing types.

Because of its insolubility in aqueous media and the high molecular weight of its components, asphalt has a low order of toxicity.

The effects on the tracheobronchial tree and lungs of mice inhaling an aerosol of petroleum asphalt and another group inhaling smoke from heated petroleum asphalt included congestion, acute bronchitis, pneumonitis, bronchial dilation, some peribronchiolar round cell infiltration, abscess formation, loss of cilia, epithelial atrophy and necrosis. The pathological changes were patchy, and in some animals were relatively refractory to treatment. It was concluded that these changes were a non-specific reaction to breathing air polluted with aromatic hydrocarbons, and that their extent was dose dependent. Guinea pigs and rats inhaling fumes from heated asphalt showed effects such as chronic fibrosing pneumonitis with peribronchial adenomatosis, and the rats developed squamous cell metaplasia, but none of the animals had malignant lesions.

Steam-refined petroleum asphalts were tested by application to the skin of mice. Skin tumours were produced by undiluted asphalts, dilutions in benzene and a fraction of steam-refined asphalt. When air-refined (oxidized) asphalts were applied to the skin of mice, no tumour was found with undiluted material, but, in one experiment, an air-refined asphalt in solvent (toluene) produced topical skin tumours. Two cracking-residue asphalts produced skin tumours when applied to the skin of mice. A pooled mixture of steam- and air-blown petroleum asphalts in benzene produced tumours at the site of application on the skin of mice. One sample of heated, air-refined asphalt injected subcutaneously into mice produced a few sarcomas at the injection sites. A pooled mixture of steam- and air-blown petroleum asphalts produced sarcomas at the site of subcutaneous injection in mice. Steam-distilled asphalts injected intramuscularly produced local sarcomas in one experiment in rats. Both an extract of road-surfacing asphalt and its emissions were mutagenic to Salmonella typhimurium.

Evidence for carcinogenicity to humans is not conclusive. A cohort of roofers exposed to both asphalts and coal tar pitches showed an excess risk for respiratory cancer. Likewise, two Danish studies of asphalt workers found an excess risk for lung cancer, but some of these workers may also have been exposed to coal tar, and they were more likely to be smokers than the comparison group. Among Minnesota (but not California) highway workers, increases were noted for leukaemia and urological cancers. Even though the epidemiological data to date are inadequate to demonstrate with a reasonable degree of scientific certainty that asphalt presents a cancer risk to humans, general agreement exists, on the basis of experimental studies, that asphalt may pose such a risk.

Safety and Health Measures

Since heated asphalt will cause severe skin burns, those working with it should wear loose clothing in good condition, with the neck closed and the sleeves rolled down. Hand and arm protection should be worn. Safety shoes should be about 15 cm high and laced so that no openings are left through which hot asphalt may reach the skin. Face and eye protection is also recommended when heated asphalt is handled. Changing rooms and proper washing and bathing facilities are desirable. At crushing plants where dust is produced and at boiling pans from which fumes escape, adequate exhaust ventilation should be provided.

Asphalt kettles should be set securely and be levelled to preclude the possibility of their tipping. Workers should stand upwind of a kettle. The temperature of heated asphalt should be checked frequently in order to prevent overheating and possible ignition. If the flash point is approached, the fire under a kettle must be put out at once and no open flame or other source of ignition should be permitted nearby. Where asphalt is being heated, fire-extinguishing equipment should be within easy reach. For asphalt fires, dry chemical or carbon dioxide types of extinguishers are considered most appropriate. The asphalt spreader and the driver of an asphalt paving machine should be offered half-face respirators with organic vapour cartridges. In addition, to prevent the inadvertent swallowing of toxic materials, workers should not eat, drink or smoke near a kettle.

If molten asphalt strikes the exposed skin, it should be cooled immediately by quenching with cold water or by some other method recommended by medical advisers. An extensive burn should be covered with a sterile dressing and the patient should be taken to a hospital; minor burns should be seen by a physician. Solvents should not be used to remove asphalt from burned flesh. No attempt should be made to remove particles of asphalt from the eyes; instead the victim should be taken to a physician at once.

Classes of bitumens / asphalts

Class 1: Penetration bitumens are classified by their penetration value. They are usually produced from the residue from atmospheric distillation of petroleum crude oil by applying further distillation under vacuum, partial oxidation (air rectification), solvent precipitation or a combination of these processes. In Australia and the United States, bitumens that are approximately equivalent to those described here are called asphalt cements or viscosity-graded asphalts, and are specified on the basis of viscosity measurements at 60°C.

Class 2: Oxidized bitumens are classified by their softening points and penetration values. They are produced by passing air through hot, soft bitumen under controlled temperature conditions. This process alters the characteristics of the bitumen to give reduced temperature susceptibility and greater resistance to different types of imposed stress. In the United States, bitumens produced using air blowing are known as air-blown asphalts or roofing asphalts and are similar to oxidized bitumens.

Class 3: Cutback bitumens are produced by mixing penetration bitumens or oxidized bitumens with suitable volatile diluents from petroleum crudes such as white spirit, kerosene or gas oil, to reduce their viscosity and render them more fluid for ease of handling. When the diluent evaporates, the initial properties of bitumen are recovered. In the United States, cutback bitumens are sometimes referred to as road oils.

Class 4: Hard bitumens are normally classified by their softening point. They are manufactured similarly to penetration bitumens, but have lower penetration values and higher softening points (i.e., they are more brittle).

Class 5: Bitumen emulsions are fine dispersions of droplets of bitumen (from classes 1, 3 or 6) in water. They are manufactured using high-speed shearing devices, such as colloid mills. The bitumen content can range from 30 to 70% by weight. They can be anionic, cationic or non-ionic. In the United States, they are referred to as emulsified asphalts.

Class 6: Blended or fluxed bitumens may be produced by blending bitumens (primarily penetration bitumens) with solvent extracts (aromatic by-products from the refining of base oils), thermally cracked residues or certain heavy petroleum distillates with final boiling points above 350°C.

Class 7: Modified bitumens contain appreciable quantities (typically 3 to 15% by weight) of special addidtives, such as polymers, elastomers, sulphur and other products used to modify their properties; they are used for specialized applications.

Class 8: Thermal bitumens were produced by extended distillation, at high temperature, of a petroleum residue. Currently, they are not manufactured in Europe or in the United States.

Source: IARC1985

Cement and Concrete

Cement

Cement is a hydraulic bonding agent used in building construction and civil engineering. It is a fine powder obtained by grinding the clinker of a clay and limestone mixture calcined at high temperatures. When water is added to cement it becomes a slurry that gradually hardens to a stone-like consistency. It can be mixed with sand and gravel (coarse aggregates) to form mortar and concrete.

There are two types of cement: natural and artificial. The natural cements are obtained from natural materials having a cement-like structure and require only calcining and grinding to yield hydraulic cement powder. Artificial cements are available in large and increasing numbers. Each type has a different composition and mechanical structure and has specific merits and uses. Artificial cements may be classified as portland cement (named after the town of Portland in the United Kingdom) and aluminous cement.

Production

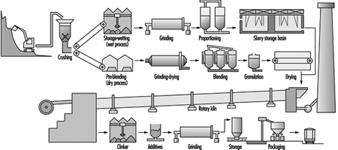

The portland process, which accounts for by far the largest part of world cement production, is illustrated in figure 1. It comprises two stages: clinker manufacture and clinker grinding. The raw materials used for clinker manufacture are calcareous materials such as limestone and argillaceous materials such as clay. The raw materials are blended and ground either dry (dry process) or in water (wet process). The pulverised mixture is calcined either in vertical or rotary-inclined kilns at a temperature ranging from 1,400 to 1,450°C. On leaving the kiln, the clinker is cooled rapidly to prevent the conversion of tricalcium silicate, the main ingredient of portland cement, into bicalcium silicate and calcium oxide.

Figure 1. The manufacture of cement

The lumps of cooled clinker are often mixed with gypsum and various other additives which control the setting time and other properties of the mixture in use. In this way it is possible to obtain a wide range of different cements such as normal portland cement, rapid-setting cement, hydraulic cement, metallurgical cement, trass cement, hydrophobic cement, maritime cement, cements for oil and gas wells, cements for highways or dams, expansive cement, magnesium cement and so on. Finally, the clinker is ground in a mill, screened and stored in silos ready for packaging and shipping. The chemical composition of normal portland cement is:

- calcium oxide (CaO): 60 to 70%

- silicon dioxide (SiO2) (including about 5% free SiO2): 19 to 24%

- aluminium trioxide (Al3O3): 4 to 7%

- ferric oxide (Fe2O3): 2 to 6%

- magnesium oxide (MgO): less than 5%

Aluminous cement produces mortar or concrete with high initial strength. It is made from a mixture of limestone and clay with a high aluminium oxide content (without extenders) which is calcined at about 1,400°C. The chemical composition of aluminous cement is approximately:

- aluminium oxide (Al2O3): 50%

- calcium oxide (CaO): 40%

- ferric oxide (Fe2O3): 6%

- silicon dioxide (SiO2): 4%

Fuel shortages lead to the increased production of natural cements, especially those using tuff (volcanic ash). If necessary, this is calcined at 1,200°C, instead of 1,400 to 1,450°C as required for portland. The tuff may contain 70 to 80% amorphous free silica and 5 to 10% quartz. With calcination the amorphous silica is partially transformed to tridimite and crystobalite.

Uses

Cement is used as a binding agent in mortar and concrete —a mixture of cement, gravel and sand. By varying the processing method or by including additives, different types of concrete may be obtained using a single type of cement (e.g., normal, clay, bituminous, asphalt tar, rapid-setting, foamed, waterproof, microporous, reinforced, stressed, centrifuged concrete and so on).

Hazards

In the quarries from which the clay, limestone and gypsum for cement are extracted, workers are exposed to the hazards of climatic conditions, dusts produced during drilling and crushing, explosions and falls of rock and earth. Road transport accidents occur during haulage to the cement works.

During cement processing, the main hazard is dust. In the past, dust levels ranging from 26 to 114 mg/m3 have been recorded in quarries and cement works. In individual processes the following dust levels were reported: clay extraction—41.4 mg/m3; raw materials crushing and milling—79.8 mg/m3; sieving— 384 mg/m3; clinker grinding—140 mg/m3; cement packing— 256.6 mg/m3; and loading, etc.—179 mg/m3. In modern factories using the wet process, 15 to 20 mg dust/m3 air are occasionally the upper short-time values. The air pollution in the neighbourhood of cement factories is around 5 to 10% of the old values, thanks in particular to the widespread use of electrostatic filters. The free silica content of the dust usually varies between the level in raw material (clay may contain fine particulate quartz, and sand may be added) and that of the clinker or the cement, from which all the free silica will normally have been eliminated.

Other hazards encountered in cement works include high ambient temperatures, especially near furnace doors and on furnace platforms, radiant heat and high noise levels (120 dB) in the vicinity of the ball mills. Carbon monoxide concentrations ranging from trace quantities up to 50 ppm have been found near limestone kilns.

Other hazardous conditions encountered in cement industry workers include diseases of the respiratory system, digestive disorders, skin diseases, rheumatic and nervous conditions and hearing and visual disorders.

Respiratory tract diseases

Respiratory tract disorders are the most important group of occupational diseases in the cement industry and are the result of inhalation of airborne dust and the effects of macroclimatic and microclimatic conditions in the workplace environment. Chronic bronchitis, often associated with emphysema, has been reported as the most frequent respiratory disease.

Normal portland cement does not cause silicosis because of the absence of free silica. However, workers engaged in cement production may be exposed to raw materials which present great variations in free silica content. Acid-resistant cements used for refractory plates, bricks and dust contain high amounts of free silica, and exposure to them involves a definite risk of silicosis.

Cement pneumoconiosis has been described as a benign pinhead or reticular pneumoconiosis, which may appear after prolonged exposure, and presents a very slow progression. However, a few cases of severe pneumoconiosis have also been observed, most likely following exposure to materials other than clay and portland cement.

Some cements also contain varying amounts of diatomaceous earth and tuff. It is reported that when heated, diatomaceous earth becomes more toxic due to the transformation of the amorphous silica into cristobalite, a crystalline substance even more pathogenic than quartz. Concomitant tuberculosis may complicate the course of the cement pneumoconiosis.

Digestive disorders

Attention has been drawn to the apparently high incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers in the cement industry. Examination of 269 cement plant workers revealed 13 cases of gastroduodenal ulcer (4.8%). Subsequently, gastric ulcers were induced in both guinea pigs and a dog fed on cement dust. However, a study at a cement works showed a sickness absence rate of 1.48 to 2.69% due to gastroduodenal ulcers. Since ulcers may pass through an acute phase several times a year, these figures are not excessive when compared with those for other occupations.

Skin diseases

Skin diseases are widely reported in the literature and have been said to account for about 25% and more of all the occupational skin diseases. Various forms have been observed, including inclusions in the skin, periungal erosions, diffuse eczematous lesions and cutaneous infections (furuncles, abscesses and panaritiums). However, these are more frequent among cement users (e.g., bricklayers and masons) than among cement manufacturing plant workers.

As early as 1947 it was suggested that cement eczema might be due to the presence in the cement of hexavalent chromium (detected by the chromium solution test). The chromium salts probably enter the dermal papillae, combine with proteins and produce a sensitization of an allergic nature. Since the raw materials used for cement manufacture do not usually contain chromium, the following have been listed as the possible sources of the chromium in cement: volcanic rock, the abrasion of the refractory lining of the kiln, the steel balls used in the grinding mills and the different tools used for crushing and grinding the raw materials and the clinker. Sensitization to chromium may be the leading cause of nickel and cobalt sensitivity. The high alkalinity of cement is considered an important factor in cement dermatoses.

Rheumatic and nervous disorders

The wide variations in macroclimatic and microclimatic conditions encountered in the cement industry have been associated with the appearance of various disorders of the locomotor system (e.g., arthritis, rheumatism, spondylitis and various muscular pains) and the peripheral nervous system (e.g., back pain, neuralgia and radiculitis of the sciatic nerves).

Hearing and vision disorders

Moderate cochlear hypoacusia in workers in a cement mill has been reported. The main eye disease is conjunctivitis, which normally requires only ambulatory medical care.

Accidents

Accidents in quarries are due in most cases to falls of earth or rock, or they occur during transportation. In cement works the main types of accidental injuries are bruises, cuts and abrasions which occur during manual handling work.

Safety and health measures

A basic requirement in the prevention of dust hazards in the cement industry is a precise knowledge of the composition and, especially, of the free silica content of all the materials used. Knowledge of the exact composition of newly-developed types of cement is particularly important.

In quarries, excavators should be equipped with closed cabins and ventilation to ensure a pure air supply, and dust suppression measures should be implemented during drilling and crushing. The possibility of poisoning due to carbon monoxide and nitrous gases released during blasting may be countered by ensuring that workers are at a suitable distance during shotfiring and do not return to the blasting point until all fumes have cleared. Suitable protective clothing may be necessary to protect workers against inclement weather.

All dusty processes in cement works (grinding, sieving, transfer by conveyor belts) should be equipped with adequate ventilation systems, and conveyor belts carrying cement or raw materials should be enclosed, with special precautions being taken at conveyor transfer points. Good ventilation is also required on the clinker cooling platform, for clinker grinding and in cement packing plants.

The most difficult dust control problem is that of the clinker kiln stacks, which are usually fitted with electrostatic filters, preceded by bag or other filters. Electrostatic filters may be used also for the sieving and packing processes, where they must be combined with other methods for air pollution control. Ground clinker should be conveyed in enclosed screw conveyors.

Hot work points should be equipped with cold air showers, and adequate thermal screening should be provided. Repairs on clinker kilns should not be undertaken until the kiln has cooled adequately, and then only by young, healthy workers. These workers should be kept under medical supervision to check their cardiac, respiratory and sweat function and prevent the occurrence of thermal shock. Persons working in hot environments should be supplied with salted drinks when appropriate.

Skin disease prevention measures should include the provision of shower baths and barrier creams for use after showering. Desensitization treatment may be applied in cases of eczema: after removal from cement exposure for 3 to 6 months to allow healing, 2 drops of 1:10,000 aqueous potassium dichromate solution is applied to the skin for 5 minutes, 2 to 3 times per week. In the absence of local or general reaction, contact time is normally increased to 15 minutes, followed by an increase in the strength of the solution. This desensitization procedure can also be applied in cases of sensitivity to cobalt, nickel and manganese. It has been found that chrome dermatitis—and even chrome poisoning—may be prevented and treated with ascorbic acid. The mechanism for the inactivation of hexavalent chromium by ascorbic acid involves reduction to trivalent chromium, which has a low toxicity, and subsequent complex formation of the trivalent species.

Concrete and Reinforced Concrete Work

To produce concrete, aggregates, such as gravel and sand, are mixed with cement and water in motor-driven horizontal or vertical mixers of various capacities installed at the construction site, but sometimes it is more economical to have ready-mixed concrete delivered and discharged into a silo on the site. For this purpose concrete mixing stations are installed in the periphery of towns or near gravel pits. Special rotary-drum lorries are used to avoid separation of the mixed constituents of the concrete, which would lower the strength of concrete structures.

Tower cranes or hoists are used to transport the ready-mixed concrete from the mixer or silo to the framework. The size and height of certain structures may also require the use of concrete pumps for conveying and placing the ready-mixed concrete. There are pumps which lift the concrete to heights of up to 100 m. As their capacity is by far greater than that of cranes of hoists, they are used in particular for the construction of high piers, towers and silos with the aid of climbing formwork. Concrete pumps are generally mounted on lorries, and the rotary-drum lorries used for transporting ready-mixed concrete are now frequently equipped to deliver the concrete directly to the concrete pump without passing through a silo.

Formwork

Formwork has followed the technical development rendered possible by the availability of larger tower cranes with longer arms and increased capacities, and it is no longer necessary to prepare shuttering in situ.

Prefabricated formwork up to 25 m2 in size is used in particular for making the vertical structures of large residential and industrial buildings, such as facades and dividing walls. These structural-steel formwork elements, which are prefabricated in the site shop or by the industry, are lined with sheet-metal or wooden panels. They are handled by crane and removed after the concrete has set. Depending on the type of building method, prefabricated formwork panels are either lowered to the ground for cleaning or taken to the next wall section ready for pouring.

So-called formwork tables are used to make horizontal structures (i.e., floor slabs for large buildings). These tables are composed of several structural-steel elements and can be assembled to form floors of different surfaces. The upper part of the table (i.e., the actual floor-slab form) is lowered by means of screw jacks or hydraulic jacks after the concrete has set. Special beak-like load-carrying devices have been devised to withdraw the tables, to lift them to the next floor and to insert them there.

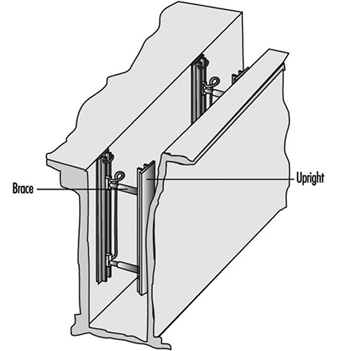

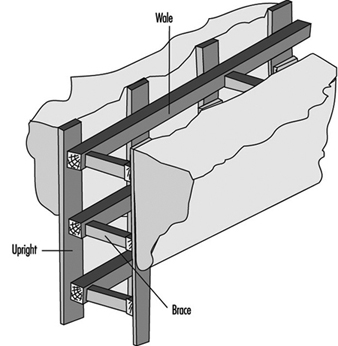

Sliding or climbing formwork is used to build towers, silos, bridge piers and similar high structures. A single formwork element is prepared in situ for this purpose; its cross-section corresponds to that of the structure to be erected, and its height may vary between 2 and 4 m. The formwork surfaces in contact with the concrete are lined with steel sheets, and the entire element is linked to jacking devices. Vertical steel bars anchored in the concrete which is poured serve as jacking guides. The sliding form is jacked upwards as the concrete sets, and the reinforcement work and concrete placing continue without interruption. This means that work has to go on around the clock.

Climbing forms differ from sliding ones in that they are anchored in the concrete by means of screw sleeves. As soon as the poured concrete has set to the required strength, the anchor screws are undone, the form is lifted to the height of the next section to be poured, anchored and prepared for receiving the concrete.

So-called form cars are frequently used in civil engineering, in particular for making bridge deck slabs. Especially when long bridges or viaducts are built, a form car replaces the rather complex falsework. The deck forms corresponding to one length of bay are fitted to a structural-steel frame so that the various form elements can be jacked into position and be removed laterally or lowered after the concrete has set. When the bay is finished, the supporting frame is advanced by one bay length, the form elements are again jacked into position, and the next bay is poured

When a bridge is built using the so-called cantilever technique the form-supporting frame is much shorter than the one described above. It does not rest on the next pier but must be anchored to form a cantilever. This technique, which is generally used for very high bridges, often relies on two such frames which are advanced by stages from piers on both sides of the span.

Prestressed concrete is used particularly for bridges, but also in building especially designed structures. Strands of steel wire wrapped in steel-sheet or plastic sheathing are embedded in the concrete at the same time as the reinforcement. The ends of the strands or tendons are provided with head plates so that the prestressed concrete elements may be pretensioned with the aid of hydraulic jacks before the elements are loaded.

Prefabricated elements

Construction techniques for large residential buildings, bridges and tunnels have been rationalized even further by prefabricating elements such as floor slabs, walls, bridge beams and so on, in a special concrete factory or near the construction site. The prefabricated elements, which are assembled on the site, do away with the erection, displacement and dismantling of complex formwork and falsework, and a great deal of dangerous work at height can be avoided.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is generally delivered to the site cut and bent according to bar and bending schedules. Only when prefabricating concrete elements on the site or in the factory are the reinforcement bars tied or welded to each other to form cages or mats which are inserted into the forms before the concrete is poured.

Prevention of accidents

Mechanization and rationalization have eliminated many traditional hazards on building sites, but have also created new dangers. For instance, fatalities due to falls from height have considerably diminished thanks to the use of form cars, form-supporting frames in bridge building and other techniques. This is due to the fact that the work platforms and walkways with their guard rails are assembled only once and displaced at the same time as the form car, whereas with traditional formwork the guard rails were often neglected. On the other hand, mechanical hazards are increasing and electrical hazards are particularly serious in wet environments. Health hazards arise from cement itself, from substances added for curing or waterproofing and from lubricants for formwork.

Some important accident prevention measures to be taken for various operations are given below.

Concrete mixing

As concrete is nearly always mixed by machine, special attention should be paid to the design and layout of switchgear and feed-hopper skips. In particular, when concrete mixers are being cleaned, a switch may be unintentionally actuated, starting the drum or the skip and causing injury to the worker. Therefore, switches should be protected and also arranged in such a manner that no confusion is possible. If necessary, they should be interlocked or provided with a lock. The skips should be free from danger zones for the mixer attendant and workers moving on passageways near it. It must also be ensured that workers cleaning the pits beneath feed-hopper skips are not injured by the accidental lowering of the hopper.

Silos for aggregates, especially sand, present a hazard of fatal accidents. For example, workers entering a silo without a standby person and without a safety harness and lifeline may fall and be buried in the loose material. Silos should therefore be equipped with vibrators and platforms from which sticking sand can be poked down, and corresponding warning notices should be displayed. No person should be allowed to enter the silo without another standing by.

Concrete handling and placing

The proper layout of concrete transfer points and their equipment with mirrors and bucket receiving cages obviates the danger of injuring a standby worker who otherwise has to reach out for the crane bucket and guide it to a proper position.

Transfer silos which are jacked up hydraulically must be secured so that they are not suddenly lowered if a pipeline breaks.

Work platforms fitted with guard rails must be provided when placing the concrete in the forms with the aid of buckets suspended from the crane hook or with a concrete pump. The crane operators must be trained for this type of work and must have normal vision. If large distances are covered, two-way telephone communication or walkie-talkies have to be used.

When concrete pumps with pipelines and placer masts are used, special attention should be paid to the stability of the installation. Agitating lorries (cement mixers) with built-in concrete pumps must be equipped with interlocked switches which make it impossible to start the two operations simultaneously. The agitators must be guarded so that the operating personnel cannot come into contact with moving parts. The baskets for collecting the rubber ball which is pressed through the pipeline to clean it after the concrete has been poured, are now replaced by two elbows arranged in opposite directions. These elbows absorb almost all the pressure needed to push the ball through the placing line; they not only eliminate the whip effect at the line end, but also prevent the ball from being shot out of the line end.

When agitating lorries are used in combination with placing plant and lifting equipment, special attention has to be paid to overhead electric lines. Unless the overhead line can be displaced they must be insulated or guarded by protective scaffolds within the work range to exclude any accidental contact. It is important to contact the power supply station.

Formwork

Falls are common during the assembly of traditional formwork composed of square timber and boards because the necessary guard rails and toe boards are often neglected for work platforms which are only required for short periods. Nowadays, steel supporting structures are widely used to speed up formwork assembly, but here again the available guard rails and toe boards are frequently not installed on the pretext that they are needed for so short a time.

Plywood form panels, which are increasingly used, offer the advantage of being easy and quick to assemble. However, often after being used several times, they are frequently misappropriated as platforms for rapidly required scaffolds, and it is generally forgotten that the distances between the supporting transoms must be considerably reduced in comparison with normal scaffold planks. Accidents resulting from breakage of form panels misused as scaffold platforms are still rather frequent.

Two outstanding hazards must be borne in mind when using prefabricated form elements. These elements must be stored in such a manner that they cannot turn over. Since it is not always feasible to store form elements horizontally, they must be secured by stays. Form elements permanently equipped with platforms, guard rails and toeboards may be attached by slings to the crane hook as well as being assembled and dismantled on the structure under construction. They constitute a safe workplace for the personnel and do away with the provision of work platforms for placing the concrete. Fixed ladders may be added for safer access to platforms. Scaffold and work platforms with guard rails and toe boards permanently attached to the form element should be used in particular with sliding and climbing formwork.

Experience has shown that accidents due to falls are rare when work platforms do not have to be improvised and rapidly assembled. Unfortunately, form elements fitted with guard rails cannot be used everywhere, especially where small residential buildings are being erected.

When the form elements are raised by crane from storage to the structure, lifting tackle of appropriate size and strength, such as slings and spreaders, must be used. If the angle between the sling legs is too large, the form elements must be handled with the aid of spreaders.

The workers cleaning the forms are exposed to a health hazard which is generally overlooked: the use of portable grinders to remove concrete residues adhering to the form surfaces. Dust measurements have shown that the grinding dust contains a high percentage of respirable fractions and silica. Therefore, dust control measures must be taken (e.g., portable grinders with exhaust devices linked to a filter unit or an enclosed form-board cleaning plant with exhaust ventilation.

Assembly of prefabricated elements

Special lifting equipment should be used in the manufacturing plant so that the elements can be moved and handled safely and without injury to the workers. Anchor bolts embedded in the concrete facilitate their handling not only in the factory but also on the assembly site. To avoid bending of the anchor bolts by oblique loads, large elements must be lifted with the aid of spreaders with short rope slings. If a load is applied to the bolts at an oblique angle, concrete may spill off and the bolts may be torn out. The use of inappropriate lifting tackle has caused serious accidents resulting from falling concrete elements.

Appropriate vehicles must be used for the road transport of prefabricated elements. They must be approximately secured against overturning or sliding—for example, when the driver has to brake the vehicle suddenly. Visibly displayed weight indications on the elements facilitate the task of the crane operator during loading, unloading and assembly on the site.

Lifting equipment on the site should be adequately chosen and operated. Tracks and roads must be kept in good condition in order to avoid overturning of loaded equipment during operation.

Work platforms protecting personnel against falls from height must be provided for the assembly of the elements. All possible means of collective protection, such as scaffolds, safety nets and overhead travelling cranes erected before completion of the building, should be taken into consideration before recourse is taken to reliance on PPE. It is, of course, possible to equip the workers with safety harnesses and lifelines, but experience has shown that there are workers who use this equipment only when they are under constant close supervision. Lifelines are indeed a hindrance when certain tasks are performed, and certain workers are proud of being capable of working at great heights without using any protection.

Before starting to design a prefabricated building, the architect, the manufacturer of the prefabricated elements and the building contractor should meet to discuss and study the course and safety of all operations. When it is known beforehand what types of handling and lifting equipment are available on the site, the concrete elements may be provided in the factory with fastening devices for guard rails and toe boards. The façade ends of floor elements, for instance, are then easily fitted with prefabricated guard rails and toe boards before the elements are lifted into place. The wall elements corresponding to the floor slab may thereafter be safely assembled because the workers are protected by guard rails.

For the erection of certain high industrial structures, mobile work platforms are lifted into position by crane and hung from suspension bolts embedded in the structure itself. In such cases it may be safer to transport the workers to the platform by crane (which should have high safety characteristics and be run by a qualified operator) than to use improvised scaffolds or ladders.

When post-tensioning concrete elements, attention should be paid to the design of the post-tensioning recesses, which should enable the tensioning jacks to be applied, operated and removed without any hazard for the personnel. Suspension hooks for tensioning jacks or openings for passing the crane rope must be provided for post-tensioning work beneath bridge decks or in box-type elements. This type of work, too, requires the provision of work platforms with guard rails and toe boards. The platform floor should be sufficiently low to allow for ample work space and safe handling of the jack. No person should be permitted at the rear of the tensioning jack because serious accidents may result from the high energy released in the breakage of an anchoring element or a steel tendon. The workers should also avoid being in front of the anchor plates as long as the mortar pressed into the tendon sheaths has not set. As the mortar pump is connected with hydraulic pipes to the jack, no person should be permitted in the area between pump and jack during tensioning. Continuous communication among the operators and with supervisors is also very important.

Training

Thorough training of plant operators in particular and all construction site personnel in general is becoming more and more important in view of increasing mechanization and the use of many types of machinery, plant and substances. Unskilled labourers or helpers should be employed in exceptional cases only, if the number of construction site accidents is to be reduced.

Elevators, Escalators and Hoists

Elevators

An elevator (lift) is a permanent lifting installation serving two or more defined landing levels, comprising an enclosed space, or car, whose dimensions and means of construction clearly permit the access of people, and which runs between rigid vertical guides. A lift, therefore, is a vehicle for raising and lowering people and/or goods from one floor to another floor within a building directly (single push-button control) or with intermediate stops (collective control).

A second category is the service lift (dumb waiter), a permanent lifting installation serving defined levels, but with a car that is too small to transport people. Service lifts transport foods and supplies in hotels and hospitals, books in libraries, mail in office buildings and so on. Generally, the floor area of such a car does not exceed 1 m2, its depth 1 m, and its height 1.20 m.

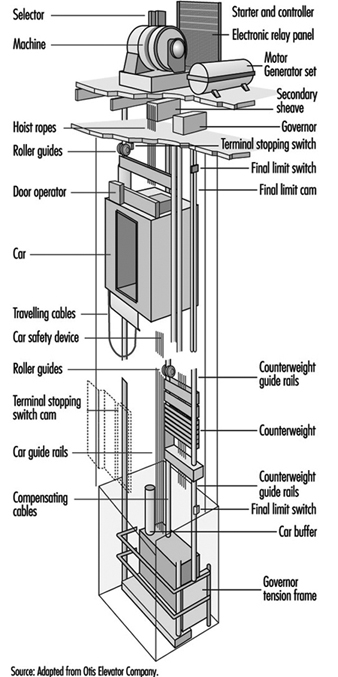

Elevators are driven directly by an electric motor (electric lifts; see figure 1) or indirectly, through the movement of a liquid under pressure generated by a pump driven by an electric motor (hydraulic lifts).

Figure 1. A cut-away view of an elevator installation showing the essential components

Electric lifts are almost exclusively driven by traction machines, geared or gearless, depending on car speed. The designation “traction” means that the power from an electric motor is transmitted to the multiple rope suspension of the car and a counterweight by friction between the specially shaped grooves of the driving or traction sheave of the machine and the ropes.

Hydraulic lifts have become widely used since the 1970s for the transport of goods and passengers, usually for a height not exceeding six floors. Hydraulic oil is used as pressure fluid. The direct-acting system with a ram supporting and moving the car is the simplest one.

Standardization

Technical Committee 178 of the ISO has drafted standards for: loads and speeds up to 2.50 m/s; car and hoistway dimensions to accommodate passengers and goods; bed and service lifts for residential buildings, offices, hotels, hospitals and nursing homes; control devices, signals and additional accessories; and selection and planning of lifts in residential buildings. Each building should be provided with at least one lift accessible to handicapped people in wheelchairs. The Association française de normalisation (AFNOR) is in charge of the Secretariat of this Technical Committee.

General safety requirements

Every industrialized country has a safety code drawn up and kept up to date by a national standards committee. Since this work was started in the 1920s, the various codes have gradually been made more similar, and differences now are generally not fundamental. Large manufacturing firms produce units that comply with the codes.

In the 1970s the ILO, in close cooperation with the International Committee for the Reglementation of Lifts (CIRA), published a code of practice for the construction and installation of lifts and service lifts and, a few years later, for escalators. These directives are intended as a guide for countries engaged in the drafting or modification of safety rules. A standardized set of safety rules for electric and hydraulic lifts, service lifts, escalators and passenger conveyors, the object being the elimination of technical barriers to trade among the member countries of the European Community, is also under the purview of the European Committee for Standardization (CEN). The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has devised a safety code for lifts and escalators.

Safety rules are aimed at several types of possible accidents with lifts: shearing, crushing, falling, impact, trapping, fire, electric shock, damage to material, accidents due to wear, and accidents due to corrosion. People to be safeguarded are: users, maintenance and inspection personnel and people outside the hoistway and the machine room. Objects to be safeguarded are: loads in the car, components of the lift installation and the building.

Committees drawing up safety rules have to assume that all components are correctly designed, are of sound mechanical and electrical construction, are made of material of adequate strength and suitable quality and are free from defects. Potential imprudent acts of users have to be taken into account.

Shearing is prevented by providing adequate clearances between moving components and between moving and fixed parts. Crushing is prevented by providing sufficient headroom at the top of the hoistway between the roof of the car in its highest position and the top of the shaft and a clear space in the pit where someone can remain safely when the car is in its lowest position. These spaces are assured by buffers or stops.

Protection against falling down the hoistway is obtained by solid landing doors and an automatic cut off that prevents movement of the cab until the doors are fully closed and locked. Landing doors of the power-operated sliding type are preferred for passenger lifts.

Impact is limited by restraining the kinetic energy of closing power-operated doors; trapping of passengers in a stalled car is prevented by providing an emergency unlocking device on the doors and a means for specially trained personnel to open them and extricate the passengers.

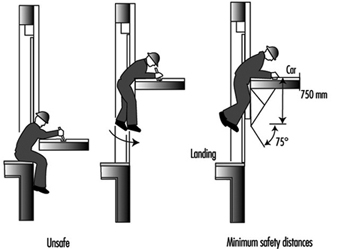

Overloading of a car is prevented by a strict ratio between the rated load and the net floor area of the car. Doors are required on all the cars passenger lifts to keep passengers from being trapped in the space between the car sill and the hoistway or the landing doors. Car sills must be fitted with a toe guard of a height of not less than 0.75 m to prevent accidents, as shown in figure 2. Cars have to be provided with safety gear capable of stopping and holding a fully loaded car in the event of overspeed or failure of the suspension. The gear is operated by an overspeed governor driven by the car by means of a rope (see figure 1). As passengers stand upright and move in a vertical direction, the retardation during the operation of the safety device should lie between 0.2 and 1.0 g (m/s2) to guard against injuries (g = standard acceleration of free fall).

Figure 2. Layout of the toe guard on the car sill to prevent trapping

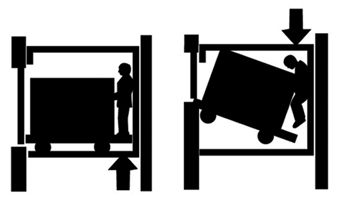

Depending on national legislation, lifts intended mainly for the transport of goods, vehicles and motor cars accompanied by authorized and instructed users may have one or two opposite car entrances not provided with car doors, under the condition that the rated speed does not exceed 0.63 m/s, the car depth is not less than 1.50 m and the wall of the hoistway facing the entrance, including the landing doors, is flush and smooth. On heavy-duty freight elevators (goods lifts), the landing doors are usually vertical bi-parting power-operated doors, which usually do not meet these conditions. In such a case, the required car door is a vertically sliding mesh gate. The clear width of the lift car and the landing doors must be the same to avoid damage to panels on the lift car by fork trucks or other vehicles entering or leaving the lift. The whole design of such a lift has to take account of the load, the weight of the handling equipment and the heavy forces involved in running, stopping and reversing these vehicles. The lift car guides require special reinforcement. When the transport of people is permitted, the number allowed should correspond to the maximum available area of the car floor. For example, the car floor area of a lift for a rated load of 2,500 kg should be 5 m2, corresponding to 33 persons. Loading and accompanying a load must be done with great care. Figure 3 shows a faulty situation.

Figure 3. Example of dangerous loading of a freight elevator (goods-lift).

Controls

All modern lifts are push-button and computer controlled, the car switch system operated by an attendant having been abandoned.

Single lifts and those grouped in two- to eight-car arrangements are usually equipped with collective controls which are interconnected in the case of multiple installations. The main feature of collective controls is that calls can be given at any moment, whether the car is moving or standstill and whether the landing doors are open or closed. Landing and car calls are collected and stored until answered. Regardless of the sequence in which they are received, calls are answered in the order that most efficiently operates the system.

Examinations and tests

Before a lift is put into service, it should be examined and tested by an organization approved by the public authorities to establish the lift’s conformity with the safety rules in the country where it has been installed. A technical dossier should be submitted to the inspector by the manufacturers. The elements to be examined and tested and the way the tests should be run are listed in the safety code. Specific tests by an approved laboratory are required for: locking devices, landing doors (possibly including fire tests), safety gear, overspeed governors and oil buffers. Certificates of the corresponding components used in the installation should be included in the register. After a lift is put into service, periodic safety examinations should be conducted, with the intervals depending on traffic volume. These tests are intended to ensure compliance with the code and the proper operation of all safety devices. Components that do not function in normal service, such as the safety gear and buffers, should be tested with a car empty and at reduced speed to prevent excessive wear and stresses that can impair the safety of a lift.

Maintenance and inspection

A lift and its components should be inspected and maintained in good and safe working order at regular intervals by competent technicians who have obtained skill and a thorough knowledge of the mechanical and electrical details of the lift and the safety rules under the guidance of a qualified instructor. Preferably the technician is employed by the supplier or erector of the lift. Normally a technician is responsible for a specific number of lifts. Maintenance involves routine servicing such as adjustment and cleaning, lubrication of moving parts, preventive servicing to anticipate possible problems, emergency visits in the case of breakdowns and major repairs, which are usually done after consultation with a supervisor. The overriding safety hazard, however, is fire. Because of the risk that a lit cigarette or other burning object might fall into the crack between the car sill and the hoistway and ignite lubricating grease in the hoistway or debris at the bottom, the hoistway should regularly be cleaned out. All systems should be at zero energy level before maintenance work is begun. In single-unit buildings, before any work is started, notices should be posted at each landing indicating that the lift is out of service.

For preventive maintenance, careful visual inspection and checks of free movement, the condition of contacts and proper operation of the equipment are generally sufficient. The hoistway equipment is inspected from the top of the car. An inspection control is provided on the car roof comprising: a bi-stable switch to bring it into operation and to neutralize the normal control, including the operation of power-operated doors. Up and down constant pressure buttons allow movement of the car at reduced speed (not exceeding 0.63 m/s). The inspection operation must remain dependent on the safety devices (closed and locked doors and so on) and it should not be possible to overrun the limits of normal travel.

A stop switch on the inspection control station prevents unexpected movement of the car. The safest direction of travel is down. The technician must be in a safe position to observe the work environment when moving the car and possess the appropriate inspection devices. The technician must have a firm hold when the car is in motion. Before leaving, the technician must report to the person in charge of the lift.

Escalators

An escalator is a continuous moving, inclined stairway which conveys passengers upward and downward. Escalators are used in commercial buildings, department stores and railway and underground stations, to guide a stream of people in a confined route from one level to another.

General safety requirements

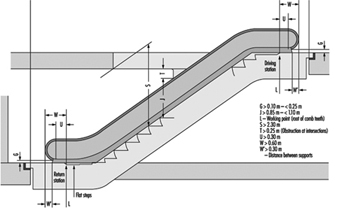

Escalators consist of a continuous chain of steps moved by a motor-driven machine by means of two roller chains, one at each side. The steps are guided by rollers on tracks which keep the step treads horizontal in the usable area. At the entrance and exit, guides ensure that over a distance of 0.80 to 1.10 m, depending on the speed and rise of the escalator, some steps form a horizontal flat surface. Step dimensions and construction are shown in figure 4. On the top of each balustrade, a handrail should be provided at a height of 0.85 to 1.10 m above the nose of the steps running parallel to the steps at substantially the same speed. The handrail at each extremity of the escalator, where the steps move horizontally, should extend at least 0.30 m beyond the landing plate and the newel including the handrail at least 0.60 m beyond (see figure 5). The handrail should enter the newel at a low point above the floor, and a guard should be installed with a safety switch to stop the escalator if fingers or hands are trapped at this point. Other risks of injury to users are formed by the clearances necessary between the side of the steps and the balustrades, between steps and combs and between treads and step risers, the latter more particularly in the upward direction at the curvature where a relative movement between consecutive steps occurs. The cleating and smoothness of the risers should prevent this risk.

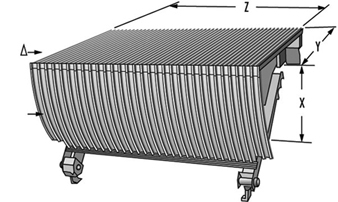

Figure 4. Escalator step unit 1 (X: Height to next step (not greater than 0.24m); Y: Depth (at least 0.38m); Z: Width (between 0.58 and 1.10m); Δ: Grooved step tread; Φ: Cleated step riser)

Figure 5. Escalator step unit 2

People may ride with their shoes sliding against the balustrade, which can cause trapping at the points where the steps straighten out. Clearly legible signs and notices, preferably pictographs, should warn and instruct users. A sign should instruct adults to hold the hands of children, who may not be able to reach the handrail, and that children should stand at all times. Both ends of an escalator should be barricaded when it is out of service.

The incline of an escalator should not exceed 30°, though it may be increased to 35° if the vertical rise is 6 m or less and the speed along the incline is limited to 0.50 m/s. Machine rooms and driving and return stations should be easily accessible to specially-trained maintenance and inspection personnel only. These spaces can lie inside the truss or be separate. The clear height should be 1.80 m with covers, if any, opened and the space should be sufficient to ensure safe working conditions. The clear height above the steps at all points should be not less than 2.30 m.

The starting, stopping or reversal of movement of an escalator should be effected by authorized people only. If the country code permits operating a system that starts automatically when a passenger moves past an electric sensor, the escalator should be in operation before the user reaches the comb. Escalators should be equipped with an inspection control system for operation during maintenance and inspection.

Maintenance and inspection

Maintenance and inspection along the lines described above for lifts are usually required by authorities. A technical dossier should be available listing the main calculation data of the supporting structure, steps, step driving components, general data, layout drawings, schematic wiring diagrams and instructions. Before an escalator is put into service, it should be examined by a person or organization approved by the public authorities; subsequently periodic inspections at given intervals are needed.

Moving Walkways (Passenger Conveyors)

A passenger conveyor, or power-driven continuous moving walkway, may be used for the conveyance of passengers between two points at the same or at different levels. Passenger conveyors are used to transport a great number of people in airports from the main station to the gates and back and in department stores and supermarkets. When the conveyors are horizontal, baby carriages, pushcarts and wheelchairs, luggage and food trolleys can be carried without risk, but on inclined conveyors these vehicles, if rather heavy, should be used only if they lock into place automatically. The ramp consists of metal pallets, similar to the step treads of escalators but longer, or rubber belt. The pallets must be grooved in the direction of travel, and combs should be placed at each end. The angle of inclination should not exceed 12° or more than 6° at the landings. The pallets and belt should move horizontally over a distance of not less than 0.40 m before entering the landing. The walkway runs between balustrades that are topped with a moving handrail that travels at substantially the same speed. The speed should not exceed 0.75 m/s unless the movement is horizontal, in which case 0.90 m/s is permitted provided the width does not exceed 1.10 m.

The safety requirements for passenger conveyors are generally similar to those for escalators and should be included in the same code.

Building Hoists

Building hoists are temporary installations used on construction sites for the transport of persons and materials. Each hoist is a guided car and should be operated by an attendant inside the car. In recent years, rack and pinion design has enabled the use of building hoists for efficient movement along radio towers or very tall smoke stacks for servicing. No one should ride a material hoist, except for inspection or maintenance.

The standards of safety vary considerably. In a few cases, these hoists are installed with the same standard of safety as permanent goods and passenger lifts in buildings, except that the hoistway is enclosed by strong wire mesh instead of solid materials to reduce the wind load. Strict regulations are needed although they need not be as strict as for passenger lifts; many countries have special regulations for these building hoists. However, in many cases the standard of safety is low, the construction poor, the hoists driven by a diesel engine winch and the car suspended by only a single steel wire rope. A building hoist should be driven by electric motors to ensure that the speed is kept within safe limits. The car should be enclosed and be provided with car entrance protections. Hoistway openings at the landings should be fitted with doors that are solid up to a height of 1 m from the floor, the upper part in wire mesh of maximum 10 x 10 mm aperture. Sills of landing doors and cars should have suitable toe guards. Cars should be provided with safety gear. One common type of accident results when workers travel on a platform hoist designed only for carrying goods, which do not have side walls or gates to keep the workers from striking a part of the scaffolding or from falling off the platform during the journey. A belt lift consists of steps on a moving vertical belt. A rider is at risk of being carried over the top, being unable to make an emergency stop, striking his or her head or shoulders on the edge of a floor opening, jumping on or off after the step has passed the floor level or being unable to reach the landing because of power failure or the belt’s stopping. Accordingly, such a lift should be used only by specially trained personnel employed by the building owner or a designee.

Fire Hazards

Generally, the hoistway for any lift extends over the full height of a building and interconnects the floors. A fire or the smoke from a fire breaking out in the lower part of a building may spread up the hoistway to other floors and, under certain circumstances, the well or hoistway may intensify a fire because of a chimney effect. Therefore, a hoistway should not form part of a building’s ventilation system. The hoistway should be totally enclosed by solid walls of non-combustible material that would not give off harmful fumes in case of a fire. A vent should be provided at the top of the lift hoistway or in the machine room above it to allow smoke to escape to open air.

Like the hoistway, the entrance doors should be fire resistant. Requirements are usually laid down in national building regulations and vary according to countries and conditions. Landing doors cannot be made smokeproof if they are to operate reliably.

No matter how tall the building, passengers should not use lifts in case of fire, because of the risks of the lift stopping at a floor in the fire zone and of passengers being trapped in the car in the event of failure of the electrical supply. In general, one lift that serves all floors is designated as a lift for firefighters that can be put at their disposal by means of a switch or special key on the main floor. The capacity, speed and car dimensions of the firefighters’ lift have to meet certain specifications. When firefighters use lifts, the normal operational controls are overridden.

The construction, maintenance and refinishing of elevator interiors, installation of carpeting and cleaning of the elevator (inside or out) may involve the use of volatile organic solvents, mastics or glues, which can present a risk to the central nervous system, as well as a fire hazard. Although these materials are used on other metal surfaces, including staircases and doors, the hazard is severe with elevators because of their small space, in which vapour concentrations can become excessive. The use of solvents on the outside of an elevator car can also be risky, again because of limited air flow, particularly in a blind hoistway, where venting may be impeded. (A blind hoistway is one without an exit door, usually extending for several floors between two destinations; where a group of elevators serves floors 20 and above, a blind hoistway would extend between floors 1 and 20.)

Lifts and Health

While lifts and hoists involve hazards, their use can also help reduce fatigue or serious muscle injury due to manual handling, and they can reduce labour costs, especially in building construction work in some developing countries. On some such sites where no lifts are used, workers have to carry heavy loads of bricks and other building materials up inclined runways numerous floors high in hot, humid weather.

Cranes

A crane is a machine with a boom, primarily designed to raise and lower heavy loads. There are two basic crane types: mobile and stationary. Mobile cranes can be mounted on motor vehicles, boats or railroad cars. Stationary cranes can be of a tower type or mounted on overhead rails. Most cranes today are power driven, though some still operate manually. Their capacity, depending on the type and size, ranges from a few kilograms to hundreds of tonnes. Cranes are also used for pile driving, dredging, digging, demolition and personnel work platforms. Generally, a crane’s capacity is greater when the load is closer to its mast (centre of rotation) and less when the load is further away from its mast.

Crane hazards

Accidents involving cranes are usually costly and spectacular. Injuries and fatalities involve not only workers, but sometimes innocent bystanders. Hazards exist in all facets of crane operation, including assembly, dismantling, travel and servicing. Some of the most common hazards involving cranes are:

- Electrical hazards. Overhead powerline contact and arcing of electrical current through the air can occur if the machine or hoist line is close enough to the powerline. When powerline contact occurs, the danger is not just limited to the operator of the hoist, but extends to all personnel in the immediate vicinity. Twenty three percent of crane fatalities in the United States, for example, in 1988–1989 involved powerline contact. Aside from injury to humans, electrical current can cause structural damage to the crane.

- Structural failure and overloading. Structural failure occurs when a crane or its rigging components are overloaded. When a crane is overloaded, the crane and its rigging components are subject to structural stresses that may cause irreversible damage. Swinging or sudden dropping of the load, using defective components, hoisting a load beyond capacity, dragging a load and side-loading a boom can cause overloading.

- Instability failure. Instability failure is more common with mobile cranes than stationary ones. When a crane moves a load, swings its boom and moves beyond its stability range, the crane has a tendency to topple. Ground conditions can also cause instability failure. When a crane is not levelled, its stability is reduced when the boom is oriented in certain directions. When a crane is positioned on ground that cannot bear its weight, the ground can give way, causing the crane to topple. Cranes have also been known to tip when travelling on poorly compacted ramps on construction sites.

- Material falling or slipping. Material can fall or slip if not properly secured. Falling material can injure workers in the vicinity or cause property damage. Undesired movement of material can pinch or crush workers involved in the rigging process.

- Improper servicing, assembling and dismantling procedures. Poor access, lack of fall protection and poor practices have injured and killed workers when servicing, assembling and dismantling cranes. This problem is most common with mobile cranes where service is performed in the field and there is lack of access equipment. Many cranes, particularly older models, do not provide handrails or steps to facilitate getting to some sections of the crane. Servicing around the boom and top of the cab is dangerous when workers walk on the boom without fall-arrest equipment. On lattice-boom cranes, incorrect loading and unloading as well as assembly and disassembly of the boom has caused sections to fall onto the workers. The boom sections were either not properly supported during these operations, or the rigging of the lines to support the boom was improper.

- Hazard to the helper or oiler. A very hazardous pitch point is created as the upper portion of a crane rotates past the stationary lower section during normal operations. All helpers working around the crane should stay clear of the deck of the crane during operation.

- Physical, chemical and stress hazards to the crane operator. When the cab is not insulated, the operator can be subjected to excessive noise, causing loss of hearing. Seats that are not properly designed can cause back pain. Lack of adjustment to the seat height and tilt can result in poor visibility from operating positions. Poor cab design also contributes to poor visibility. Exhaust from gasoline or diesel engines on cranes contains fumes that are hazardous in confined areas. There is also concern over the effect of whole-body vibration from the engine, particularly in older cranes. Time constraints or fatigue can also play a part in crane accidents.

Control Measures

Safe operation of a crane is the responsibility of all parties involved. Crane manufacturers are responsible for designing and manufacturing cranes that are stable and structurally sound. Cranes must be rated properly so that there are enough safeguards to prevent accidents caused by overloading and instability. Instruments such as load-limiting devices and angle and boom length indicators aid operators in the safe operation of a crane. (Powerline sensory devices have proved to be unreliable.) Every crane should have a reliable, efficient, automatic safe- load indicator. In addition, crane manufacturers must make accommodations in the design that facilitate safe access for servicing and safe operation. Hazards can be reduced by clear design of control panels, providing a chart at the operator’s fingertips that specifies load configurations, handrails, non-glare windows, windows that extend to the cab floor, comfortable seats and both noise and thermal insulation. In some climates, heated and air-conditioned cabs contribute to the worker’s comfort and reduce fatigue.