Working Under Increased Barometric Pressure

The atmosphere normally consists of 20.93% oxygen. The human body is naturally adapted to breathe atmospheric oxygen at a pressure of approximately 160 torr at sea level. At this pressure, haemoglobin, the molecule which carries oxygen to the tissue, is approximately 98% saturated. Higher pressures of oxygen cause little important increase in oxyhaemoglobin, since its concentration is virtually 100% to begin with. However, significant amounts of unburnt oxygen may pass into physical solution in the blood plasma as the pressure rises. Fortunately, the body can tolerate a fairly wide range of oxygen pressures without appreciable harm, at least in the short term. Longer term exposures may lead to oxygen toxicity problems.

When a job requires breathing compressed air, as in diving or caisson work, oxygen deficiency (hypoxia) is rarely a problem, as the body will be exposed to an increasing amount of oxygen as the absolute pressure rises. Doubling the pressure will double the number of molecules inhaled per breath while breathing compressed air. Thus the amount of oxygen breathed is effectively equal to 42%. In other words, a worker breathing air at a pressure of 2 atmospheres absolute (ATA), or 10 m beneath the sea, will breathe an amount of oxygen equal to breathing 42% oxygen by mask on the surface.

Oxygen toxicity

On the earth’s surface, human beings can safely continuously breathe 100% oxygen for between 24 and 36 hours. After that, pulmonary oxygen toxicity ensues (the Lorrain-Smith effect). The symptoms of lung toxicity consist of substernal chest pain; dry, non-productive cough; a drop in the vital capacity; loss of surfactant production. A condition known as patchy atelectasis is seen on x-ray examination, and with continued exposure microhaemorrhages and ultimately production of permanent fibrosis in the lung will develop. All stages of oxygen toxicity through the microhaemorrhage state are reversible, but once fibrosis sets in, the scarring process becomes irreversible. When 100% oxygen is breathed at 2 ATA, (a pressure of 10 m of sea water), the early symptoms of oxygen toxicity become manifest after about six hours. It should be noted that interspersing short, five-minute periods of air breathing every 20 to 25 minutes can double the length of time required for symptoms of oxygen toxicity to appear.

Oxygen can be breathed at pressures below 0.6 ATA without ill effect. For example, a worker can tolerate 0.6 atmosphere oxygen breathed continuously for two weeks without any loss of vital capacity. The measurement of vital capacity appears to be the most sensitive indicator of early oxygen toxicity. Divers working at great depths may breathe gas mixtures containing up to 0.6 atmospheres oxygen with the rest of the breathing medium consisting of helium and/or nitrogen. Six tenths of an atmosphere corresponds to breathing 60% oxygen at 1 ATA or at sea level.

At pressures greater than 2 ATA, pulmonary oxygen toxicity no longer becomes the primary concern, as oxygen can cause seizures secondary to cerebral oxygen toxicity. Neurotoxicity was first described by Paul Bert in 1878 and is known as the Paul Bert effect. If a person were to breathe 100% oxygen at a pressure of 3 ATA for much longer than three continuous hours, he or she will very likely suffer a grand mal seizure. Despite over 50 years of active research as to the mechanism of oxygen toxicity of the brain and lung, this response is still not completely understood. Certain factors are known, however, to enhance toxicity and to lower the seizure threshold. Exercise, CO2 retention, use of steroids, presence of fever, chilling, ingestion of amphetamines, hyperthyroidism and fear can have an oxygen tolerance effect. An experimental subject lying quietly in a dry chamber at pressure has much greater tolerance than a diver who is working actively in cold water underneath an enemy ship, for example. A military diver may experience cold, hard exercise, probable CO2 build-up using a closed-circuit oxygen rig, and fear, and may experience a seizure within 10-15 minutes working at a depth of only 12 m, whereas a patient lying quietly in a dry chamber may easily tolerate 90 minutes at a pressure of 20 m without great danger of seizure. Exercising divers may be exposed to partial pressure of oxygen up to 1.6 ATA for short periods up to 30 minutes, which corresponds to breathing 100% oxygen at a depth of 6 m. It is important to note that one should never expose anyone to 100% oxygen at a pressure greater than 3 ATA, nor for a time longer than 90 minutes at that pressure, even with a subject quietly recumbent.

There is considerable individual variation in susceptibility to seizure between individuals and, surprisingly, within the same individual, from day to day. For this reason, “oxygen tolerance” tests are essentially meaningless. Giving seizure-suppressing drugs, such as phenobarbital or phenytoin, will prevent oxygen seizures but do nothing to mitigate permanent brain or spinal cord damage if pressure or time limits are exceeded.

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide can be a serious contaminant of the diver’s or caisson worker’s breathing air. The most common sources are internal combustion engines, used to power compressors, or other operating machinery in the vicinity of the compressors. Care should be taken to be sure that compressor air intakes are well clear of any sources of engine exhaust. Diesel engines usually produce little carbon monoxide but do produce large quantities of oxides of nitrogen, which can produce serious toxicity to the lung. In the United States, the current federal standard for carbon monoxide levels in inspired air is 35 parts per million (ppm) for an 8-hour working day. For example, at the surface even 50 ppm would not produce detectable harm, but at a depth of 50 m it would be compressed and produce the effect of 300 ppm. This concentration can produce a level of up to 40% carboxyhaemoglobin over a period of time. The actual analysed parts per million must be multiplied by the number of atmospheres at which it is delivered to the worker.

Divers and compressed-air workers should become aware of the early symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning, which include headache, nausea, dizziness and weakness. It is important to ensure that the compressor intake be always located upwind from the compressor engine exhaust pipe. This relationship must be continually checked as the wind changes or the vessels position shifts.

For many years it was widely assumed that carbon monoxide would combine with the body’s haemoglobin to produce carboxyhaemoglobin, causing its lethal effect by blocking transport of oxygen to the tissues. More recent work shows that although this effect does cause tissue hypoxia, it is not in itself fatal. The most serious damage occurs at the cellular level due to direct toxicity of the carbon monoxide molecule. Lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, which can only be terminated by hyperbaric oxygen treatment, appears to be the main cause of death and long-term sequelae.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a normal product of metabolism and is eliminated from the lungs through the normal process of respiration. Various types of breathing apparatus, however, can impair its elimination or cause high levels to build up in the diver’s inspired air.

From a practical point of view, carbon dioxide can exert deleterious effects on the body in three ways. First, in very high concentrations (above 3%), it can cause judgmental errors, which at first may amount to inappropriate euphoria, followed by depression if the exposure is prolonged. This, of course, can have serious consequences for a diver under water who wants to maintain good judgement to remain safe. As the concentration climbs, CO2 will eventually produce unconsciousness when levels rise much above 8%. A second effect of carbon dioxide is to exacerbate or worsen nitrogen narcosis (see below). At partial pressures of above 40 mm Hg, carbon dioxide begins to have this effect (Bennett and Elliot 1993). At high PO2‘s, such as one is exposed to in diving, the respiratory drive due to high CO2 is attenuated and it is possible under certain conditions for divers who tend to retain CO2 to increase their levels of carbon dioxide sufficient to render them unconscious. The final problem with carbon dioxide under pressure is that, if the subject is breathing 100% oxygen at pressures greater than 2 ATA, the risk for seizures is greatly enhanced as carbon dioxide levels rise. Submarine crews have easily tolerated breathing 1.5% CO2 for two months at a time with no functional ill effect, a concentration that is thirty times the normal concentration found in atmospheric air. Five thousand ppm, or ten times the level found in normal fresh air, is considered safe for the purposes of industrial limits. However, even 0.5% CO2 added to 100% oxygen mix will predispose a person to seizures when breathed at increased pressure.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is an inert gas with regard to normal human metabolism. It does not enter into any form of chemical combination with compounds or chemicals within the body. However, it is responsible for severe impairment in a diver’s mental functioning when breathed under high pressure.

Nitrogen behaves as an aliphatic anaesthetic as atmospheric pressure increases, which results in the concentration of nitrogen also increasing. Nitrogen fits well into the Meyer-Overton hypothesis which states that any aliphatic anaesthetic will exhibit anaesthetic potency in direct proportion to its oil-water solubility ratio. Nitrogen, which is five times more soluble in fat than in water, produces an anaesthetic effect precisely at the predicted ratio.

In actual practice, diving to depths of 50 m can be accomplished with compressed-air, although the effects of nitrogen narcosis first become evident between 30 and 50 m. Most divers, however, can function adequately within these parameters. Deeper than 50 m, helium/oxygen mixtures are commonly used to avoid the effects of nitrogen narcosis. Air diving has been done to depths of slightly over 90 m, but at these extreme pressures, the divers were barely able to function and could hardly remember what tasks they had been sent down to accomplish. As noted earlier, any excess CO2 build-up further worsens the effect of nitrogen. Because ventilatory mechanics are affected by the density of gas at great pressures, there is an automatic CO2 build-up in the lung because of changes in laminar flow within the bronchioles and the diminution of the respiratory drive. Thus, air diving deeper than 50 m can be extremely dangerous.

Nitrogen exerts its effect by its simple physical presence dissolved in neural tissue. It causes a slight swelling of the neuronal cell membrane, which makes it more permeable to sodium and potassium ions. It is felt that interference with the normal depolarization/repolarization process is responsible for clinical symptoms of nitrogen narcosis.

Decompression

Decompression tables

A decompression table sets out the schedule, based on depth and time of exposure, for decompressing a person who has been exposed to hyperbaric conditions. Some general statements can be made about decompression procedures. No decompression table can be guaranteed to avoid decompression illness (DCI) for everyone, and indeed as described below, many problems have been noted with some tables currently in use. It must be remembered that bubbles are produced during every normal decompression, no matter how slow. For this reason, although it can be stated that the longer the decompression the less the likelihood of DCI, at the extreme of least likelihood, DCI becomes an essentially random event.

Habituation

Habituation, or acclimatization, occurs in divers and compressed-air workers, and renders them less susceptible to DCI after repeated exposures. Acclimatization can be produced after about a week of daily exposure, but it is lost after an absence from work of between 5 days to a week or by a sudden increase in pressure. Unfortunately construction companies have relied on acclimatization to make work possible with what are viewed as grossly inadequate decompression tables. To maximize the utility of acclimatization, new workers are often started at midshift to allow them to habituate without getting DCI. For example, the present Japanese Table 1 for compressed-air workers utilizes the split shift, with a morning and afternoon exposure to compressed air with a surface interval of one hour between exposures. Decompression from the first exposure is about 30% of that required by the US Navy and the decompression from the second exposure is only 4% of that required by the Navy. Nevertheless, habituation makes this departure from physiologic decompression possible. Workers with even ordinary susceptibility to decompression illness self-select themselves out of compressed-air work.

The mechanism of habituation or acclimatization is not understood. However, even if the worker is not experiencing pain, damage to brain, bone, or tissue may be taking place. Up to four times as many changes are visible on MRIs taken of the brains of compressed-air workers compared to age-matched controls that have been studied (Fueredi, Czarnecki and Kindwall 1991). These probably reflect lacunar infarcts.

Diving decompression

Most modern decompression schedules for divers and caisson workers are based on mathematical models akin to those developed originally by J.S. Haldane in 1908 when he made some empirical observations on permissible decompression parameters. Haldane observed that a pressure reduction of one half could be tolerated in goats without producing symptoms. Using this as a starting point, he then, for mathematical convenience, conceived of five different tissues in the body loading and unloading nitrogen at varying rates based on the classical half time equation. His staged decompression tables were then designed to avoid exceeding a 2:1 ratio in any of the tissues. Over the years, Haldane’s model has been modified empirically in attempts to make it fit what divers were observed to tolerate. However, all mathematical models for the loading and elimination of gases are flawed, since there are no decompression tables which remain as safe or become safer as time and depth are increased.

Probably the most reliable decompression tables currently available for air diving are those of the Canadian Navy, known as the DCIEM tables (Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine). These tables were tested thoroughly by non-habituated divers over a wide range of conditions and produce a very low rate of decompression illness. Other decompression schedules which have been well tested in the field are the French National Standards, originally developed by Comex, the French diving company.

The US Navy Air Decompression tables are unreliable, especially when pushed to their limits. In actual use, US Navy Master Divers routinely decompress for a depth 3 m (10 ft) deeper and/or one exposure time segment longer than required for the actual dive to avoid problems. The Exceptional Exposure Air Decompression Tables are particularly unreliable, having produced decompression illness on 17% to 33% of all the test dives. In general, the US Navy’s decompression stops are probably too shallow.

Tunnelling and caisson decompression

None of the air decompression tables which call for air breathing during decompression, currently in wide use, appear to be safe for tunnel workers. In the United States, the current federal decompression schedules (US Bureau of Labor Statuties 1971), enforced by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), have been shown to produce DCI in one or more workers on 42% of the working days while being used at pressures between 1.29 and 2.11 bar. At pressures over 2.45 bar, they have been shown to produce a 33% incidence of aseptic necrosis of the bone (dysbaric osteonecrosis). The British Blackpool Tables are also flawed. During the building of the Hong Kong subway, 83% of the workers using these tables complained of symptoms of DCI. They have also been shown to produce an incidence of dysbaric osteonecrosis of up to 8% at relatively modest pressures.

The new German oxygen decompression tables devised by Faesecke in 1992 have been used with good success in a tunnel under the Kiel Canal. The new French oxygen tables also appear to be excellent by inspection but have not yet been used on a large project.

Using a computer which examined 15 years of data from successful and unsuccessful commercial dives, Kindwall and Edel devised compressed-air caisson decompression tables for the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in 1983 (Kindwall, Edel and Melton 1983) using an empirical approach which avoided most of the pitfalls of mathematical modelling. Modelling was used only to interpolate between real data points. The research upon which these tables was based found that when air was breathed during decompression, the schedule in the tables did not produce DCI. However, the times used were prohibitively long and therefore impractical for the construction industry. When an oxygen variant of the table was computed, however, it was found that decompression time could be shortened to times similar to, or even shorter than, the current OSHA-enforced air decompression tables cited above. These new tables were subsequently tested by non-habituated subjects of varying ages at pressures ranging from 0.95 bar to 3.13 bar in 0.13 bar increments. Average work levels were simulated by weight lifting and treadmill walking during exposure. Exposure times were as long as possible, in keeping with the combined work time and decompression time fitting into an eight-hour work day. These are the only schedules which will be used in actual practice for shift work. No DCI was reported during these tests and bone scan and x ray failed to reveal any dysbaric osteonecrosis. To date, these are the only laboratory-tested decompression schedules in existence for compressed-air workers.

Decompression of hyperbaric chamber personnel

US Navy air decompression schedules were designed to produce a DCI incidence of less than 5%. This is satisfactory for operational diving, but much too high to be acceptable for hyperbaric workers who work in clinical settings. Decompression schedules for hyperbaric chamber attendants can be based on naval air decompression schedules, but since exposures are so frequent and thus are usually at the limits of the table, they must be liberally lengthened and oxygen should be substituted for compressed-air breathing during decompression. As a prudent measure, it is recommended that a two-minute stop be made while breathing oxygen, at least three metres deeper than called for by the decompression schedule chosen. For example, while the US Navy requires a three-minute decompression stop at three metres, breathing air, after a 101 minute exposure at 2.5 ATA, an acceptable decompression schedule for a hyperbaric chamber attendant undergoing the same exposure would be a two-minute stop at 6 m breathing oxygen, followed by ten minutes at 3 m breathing oxygen. When these schedules, modified as above, are used in practice, DCI in an inside attendant is an extreme rarity (Kindwall 1994a).

In addition to providing a fivefold larger “oxygen window” for nitrogen elimination, oxygen breathing offers other advantages. Raising the PO2 in venous blood has been demonstrated to lessen blood sludging, reduce the stickiness of white cells, reduce the no-reflow phenomenon, render red cells more flexible in passing through capillaries and counteract the vast decrease in deformability and filterability of white cells which have been exposed to compressed air.

Needless to say, all workers using oxygen decompression must be thoroughly trained and apprised of the fire danger. The environment of the decompression chamber must be kept free of combustibles and ignition sources, an overboard dump system must be used to convey exhaled oxygen out of the chamber and redundant oxygen monitors with a high oxygen alarm must be provided. The alarm should sound if oxygen in the chamber atmosphere exceeds 23%.

Working with compressed air or treating clinical patients under hyperbaric conditions sometimes can accomplish work or effect remission in disease that would otherwise be impossible. When rules for the safe use of these modalities are observed, workers need not be at significant risk for dysbaric injury.

Caisson Work and Tunnelling

From time to time in the construction industry it is necessary to excavate or tunnel through ground which is either fully saturated with water, lying below the local water table, or following a course completely under water, such as a river or lake bottom. A time-tested method for managing this situation has been to apply compressed air to the working area to force water out of the ground, drying it sufficiently so that it can be mined. This principle has been applied to both caissons used for bridge pier construction and soft ground tunnelling (Kindwall 1994b).

Caissons

A caisson is simply a large, inverted box, made to the dimensions of the bridge foundation, which typically is built in a dry dock and then floated into place, where it is carefully positioned. It is then flooded and lowered until it touches bottom, after which it is driven down further by adding weight as the bridge pier itself is constructed. The purpose of the caisson is to provide a method for cutting through soft ground to land the bridge pier on solid rock or a good geologic weight-bearing stratum. When all sides of the caisson have been embedded in the mud, compressed air is applied to the interior of the caisson and water is forced out, leaving a muck floor which can be excavated by men working within the caisson. The edges of the caisson consist of a wedge-shaped cutting shoe, made of steel, which continues to descend as earth is removed beneath the descending caisson and weight is applied from above as the bridge tower is constructed. When bed rock is reached, the working chamber is filled with concrete, becoming the permanent base for the bridge foundation.

Caissons have been used for nearly 150 years and have been successful in the construction of foundations as deep as 31.4 m below mean high water, as on Bridge Pier No. 3 of the Auckland, New Zealand, Harbour Bridge in 1958.

Design of the caisson usually provides for an access shaft for workers, who can descend either by ladder or by a mechanical lift and a separate shaft for buckets to remove the spoil. The shafts are provided with hermetically sealed hatches at either end which enable the caisson pressure to remain the same while workers or materials exit or enter. The top hatch of the muck shaft is provided with a pressure sealed gland through which the hoist cable for the muck bucket can slide. Before the top hatch is opened, the lower hatch is shut. Hatch interlocks may be necessary for safety, depending on design. Pressure must be equal on both sides of any hatch before it can be opened. Since the walls of the caisson are generally made of steel or concrete, there is little or no leakage from the chamber while under pressure except under the edges. The pressure is raised incrementally to a pressure just slightly greater than is necessary to balance off sea pressure at the edge of the cutting shoe.

People working in the pressurized caisson are exposed to compressed air and may experience many of the same physiologic problems that face deep-sea divers. These include decompression illness, barotrauma of the ears, sinus cavities and lungs and if decompression schedules are inadequate, the long-term risk of aseptic necrosis of the bone (dysbaric osteonecrosis).

It is important that a ventilation rate be established to carry away CO2 and gases emanating from the muck floor (especially methane) and whatever fumes may be produced from welding or cutting operations in the working chamber. A rule of thumb is that six cubic metres of free air per minute must be provided for each worker in the caisson. Allowance must also be made for air which is lost when the muck lock and man lock are used for the passage of personnel and materials. As the water is forced down to a level exactly even with the cutting shoe, ventilation air is required as the excess bubbles out under the edges. A second air supply, equal in capacity to the first, with an independent power source, should be available for emergency use in case of compressor or power failure. In many areas this is required by law.

Sometimes if the ground being mined is homogeneous and consists of sand, blow pipes can be erected to the surface. The pressure in the caisson will then extract the sand from the working chamber when the end of the blow pipe is located in a sump and the excavated sand is shovelled into the sump. If coarse gravel, rock, or boulders are encountered, these have to be broken up and removed in conventional muck buckets.

If the caisson should fail to sink despite the added weight on top, it may sometimes be necessary to withdraw the workers from the caisson and reduce the air pressure in the working chamber to allow the caisson to fall. Concrete must be placed or water admitted to the wells within the pier structure surrounding the air shafts above the caisson to reduce the stress on the diaphragm at the top of the working chamber. When just beginning a caisson operation, safety cribs or supports should be kept in the working chamber to prevent the caisson from suddenly dropping and crushing the workers. Practical considerations limit the depth to which air-filled caissons can be driven when men are used to hand mine the muck. A pressure of 3.4 kg/cm2 gauge (3.4 bar or 35 m of fresh water) is about the maximum tolerable limit because of decompression considerations for the workers.

An automated caisson excavating system has been developed by the Japanese wherein a remotely operated hydraulically powered backhoe shovel, which can reach all corners of the caisson, is used for excavation. The backhoe, under television control from the surface, drops the excavated muck into buckets which are hoisted remotely from the caisson. Using this system, the caisson can proceed down to almost unlimited pressures. The only time that workers need enter the working chamber is to repair the excavating machinery or to remove or demolish large obstacles which appear below the cutting shoe of the caisson and which cannot be removed by the remote-controlled backhoe. In such cases, workers enter for short periods much as divers and can breathe either air or mixed gas at higher pressures to avoid nitrogen narcosis.

When people have worked long shifts under compressed-air at pressures greater than 0.8 kg/cm2 (0.8 bar), they must decompress in stages. This can be accomplished either by attaching a large decompression chamber to the top of the man shaft into the caisson or, if space requirements are such at the top that this is impossible, by attaching “blister locks” to the man shaft. These are small chambers which can accommodate only a few workers at a time in a standing position. Preliminary decompression is taken in these blister locks, where the time spent is relatively short. Then, with considerable excess gas remaining in their bodies, the workers rapidly decompress to the surface and quickly move to a standard decompression chamber, sometimes located on an adjacent barge, where they are repressurized for subsequent slow decompression. In compressed-air work, this process is known as “decanting” and was fairly common in England and elsewhere, but is prohibited in the United States. The object is to return workers to pressure within five minutes, before bubbles can grow sufficiently in size to cause symptoms. However, this is inherently dangerous because of the difficulties of moving a large gang of workers from one chamber to another. If one worker has trouble clearing his ears during repressurization, the whole shift is placed in jeopardy. There is a much safer procedure, called “surface decompression”, for divers, where only one or two are decompressed at the same time. Despite every precaution on the Auckland Harbour Bridge project, as many as eight minutes occasionally elapsed before bridge workers could be put back under pressure.

Compressed air tunnelling

Tunnels are becoming increasingly important as the population grows, both for the purposes of sewage disposal and for unobstructed traffic arteries and rail service beneath large urban centres. Often, these tunnels must be driven through soft ground considerably below the local water table. Under rivers and lakes, there may be no other way to ensure the safety of the workers than to put compressed air on the tunnel. This technique, using a hydraulically driven shield at the face with compressed air to hold back the water, is known as the plenum process. Under large buildings in a crowded city, compressed air may be necessary to prevent surface subsidence. When this occurs, large buildings can develop cracks in their foundations, sidewalks and streets may drop and pipes and other utilities can be damaged.

To apply pressure to a tunnel, bulkheads are erected across the tunnel to provide the pressure boundary. On smaller tunnels, less than three metres in diameter, a single or combination lock is used to provide access for workers and materials and removal of the excavated ground. Removable track sections are provided by the doors so that they may be operated without interference from the muck-train rails. Numerous penetrations are provided in these bulkheads for the passage of high-pressure air for the tools, low-pressure air for pressurizing the tunnel, fire mains, pressure gauge lines, communications lines, electrical power lines for lighting and machinery and suction lines for ventilation and removal of water in the invert. These are often termed blow lines or “mop lines”. The low-pressure air supply pipe, which is 15-35 cm in diameter, depending on the size of the tunnel, should extend to the working face in order to ensure good ventilation for the workers. A second low-pressure air pipe of equal size should also extend through both bulkheads, terminating just inside the inner bulkhead, to provide air in the event of rupture or break in the primary air supply. These pipes should be fitted with flapper valves which will close automatically to prevent depressurization of the tunnel if the supply pipe is broken. The volume of air required to efficiently ventilate the tunnel and keep CO2 levels low will vary greatly depending on the porosity of the ground and how close the finished concrete lining has been brought to the shield. Sometimes micro-organisms in the soil produce large amounts of CO2. Obviously, under such conditions, more air will be required. Another useful property of compressed air is that it tends to force explosive gases such as methane away from the walls and out of the tunnel. This holds true when mining areas where spilled solvents such as petrol or degreasers have saturated the ground.

A rule of thumb developed by Richardson and Mayo (1960) is that the volume of air required usually can be calculated by multiplying the area of the working face in square metres by six and adding six cubic metres per man. This gives the number of cubic metres of free air required per minute. If this figure is used, it will cover most practical contingencies.

The fire main must also extend through to the face and be provided with hose connections every sixty metres for use in case of fire. Thirty metres of rotproof hose should be attached to the water-filled fire main outlets.

In very large tunnels, over about four metres in diameter, two locks should be provided, one termed the muck lock, for passing muck trains, and the man lock, usually positioned above the muck lock, for the workers. On large projects, the man lock is often made of three compartments so that engineers, electricians and others can lock in and out past a work shift undergoing decompression. These large man locks are usually built external to the main concrete bulkhead so they do not have to resist the external compressive force of the tunnel pressure when open to the outside air.

On very large subaqueous tunnels a safety screen is erected, spanning the upper half of the tunnel, to afford some protection should the tunnel suddenly flood secondary to a blow-out while tunnelling under a river or lake. The safety screen is usually placed as close as practicable to the face, avoiding the excavating machinery. A flying gangway or hanging walkway is used between the screen and the locks, the gangway dropping down to pass at least a metre below the lower edge of the screen. This will allow the workers egress to the man lock in the event of sudden flooding. The safety screen can also be used to trap light gases which may be explosive and a mop line can be attached through the screen and coupled to a suction or blow line. With the valve cracked, this will help to purge any light gases from the working environment. Because the safety screen extends nearly down to the centre of the tunnel, the smallest tunnel it can be employed on is about 3.6 m. It should be noted that workers must be warned to keep clear of the open end of the mop line, as serious accidents can be caused if clothing is sucked into the pipe.

Table 1 is a list of instructions which should be given to compressed-air workers before they first enter the compressed-air environment.

It is the responsibility of the retained physician or occupational health professional for the tunnel project to ensure that air purity standards are maintained and that all safety measures are in effect. Adherence to established decompression schedules by periodically examining the pressure recording graphs from the tunnel and man locks must also be carefully monitored.

Table 1. Instructions for compressed-air workers

- Never “short” yourself on the decompression times prescribed by your employer and the official decompression code in use. The time saved is not worth the risk of decompression illness (DCI), a potentially fatal or crippling disease.

- Do not sit in a cramped position during decompression. To do so allows nitrogen bubbles to gather and concentrate in the joints, thereby contributing to the risk of DCI. Because you are still eliminating nitrogen from your body after you go home, you should refrain from sleeping or resting in a cramped position after work, as well.

- Warm water should be used for showers and baths up to six hours after decompressing; very hot water can actually bring on or aggravate a case of decompression illness.

- Severe fatigue, lack of sleep and heavy drinking the night before can also help bring on decompression illness. Drinking alcohol and taking aspirin should never be used as a “treatment” for pains of decompression illness.

- Fever and illness, such as bad colds, increase the risk of decompression illness. Strains and sprains in muscles and joints are also “favourite” places for DCI to begin.

- When stricken by decompression illness away from the job site, immediately contact the company’s physician or one knowledgeable in treating this disease. Wear your identifying bracelet or badge at all times.

- Leave smoking materials in the changing shack. Hydraulic oil is flammable and should a fire start in the closed environment of the tunnel, it could cause extensive damage and a shutdown of the job, which would lay you off work. Also, because the air is thicker in the tunnel due to compression, heat is conducted down cigarettes so that they become too hot to hold as they get shorter.

- Do not bring thermos bottles in your lunch box unless you loosen the stopper during compression; if you do not do this, the stopper will be forced deep into the thermos bottle. During decompression, the stopper must also be loosened so that the bottle does not explode. Very fragile glass thermos bottles might implode when pressure is applied, even if the stopper is loose.

- When the air lock door has been closed and pressure is applied, you will notice that the air in the air lock gets warm. This is called the “heat of compression” and is normal. Once the pressure stops changing, the heat will dissipate and the temperature will return to normal. During compression, the first thing you will notice is a fullness of your ears. Unless you “clear your ears” by swallowing, yawning, or holding your nose and trying to “blow the air out through your ears”, you will experience ear pain during compression. If you cannot clear your ears, notify the shift foreman immediately so that compression can be halted. Otherwise you may break your eardrums or develop a severe ear squeeze. Once you have reached maximum pressure, there will be no further problems with your ears for the remainder of the shift.

- Should you experience buzzing in your ears, ringing in your ears, or deafness following compression which persists for more than a few hours, you must report to the compressed-air physician for evaluation. Under extremely severe but rare conditions, a portion of the middle ear structure other than the eardrum may be affected if you have had a great deal of difficulty clearing your ears and in that case this must be surgically corrected within two or three days to avoid permanent difficulty.

- If you have a cold or an attack of hay fever, it is best not to try compressing in the air lock until you are over it. Colds tend to make it difficult or impossible for you to equalize your ears or sinuses.

Hyperbaric chamber workers

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is becoming more common in all areas of the world, with some 2,100 hyperbaric chamber facilities now functioning. Many of these chambers are multiplace units, which are compressed with compressed air to pressures ranging from 1 to 5 kg/cm2 gauge. Patients are given 100% oxygen to breathe, at pressures up to 2 kg/cm2 gauge. At pressures greater than that they may breathe mixed gas for treatment of decompression illness. The chamber attendants, however, typically breathe compressed air and so their exposure in the chamber is similar to that experienced by a diver or compressed-air worker.

Typically the chamber attendant working inside a multiplace chamber is a nurse, respiratory therapist, former diver, or hyperbaric technician. The physical requirements for such workers are similar to those for caisson workers. It is important to remember, however, that a number of chamber attendants working in the hyperbaric field are female. Women are no more likely to suffer ill effects from compressed-air work than men, with the exception of the question of pregnancy. Nitrogen is carried across the placenta when a pregnant woman is exposed to compressed air and this is transferred to the foetus. Whenever decompression takes place, nitrogen bubbles form in the venous system. These are silent bubbles and, when small, do no harm, as they are removed efficiently by the pulmonary filter. The wisdom, however, of having these bubbles appear in a developing foetus is doubtful. What studies have been done indicate that foetal damage may occur under such circumstances. One survey suggested that birth defects are more common in the children of women who have engaged in scuba diving while pregnant. Exposure of pregnant women to hyperbaric chamber conditions should be avoided and appropriate policies consistent with both medical and legal considerations must be developed. For this reason, female workers should be precautioned about the risks during pregnancy and appropriate personnel job assignment and health education programmes should be instituted in order that pregnant women not be exposed to hyperbaric chamber conditions.

It should be pointed out, however, that patients who are pregnant may be treated in the hyperbaric chamber, as they breathe 100% oxygen and are therefore not subject to nitrogen embolization. Previous concerns that the foetus would be at increased risk for retrolental fibroplasia or retinopathy of the newborn have proven to be unfounded in large clinical trials. Another condition, premature closure of the patent ductus arteriosus, has also not been found to be related to the exposure.

Other Hazards

Physical injuries

Divers

In general, divers are prone to the same types of physical injury that any worker is liable to sustain when working in heavy construction. Breaking cables, failing loads, crush injuries from machines, turning cranes and so on, can be commonplace. However, in the underwater environment, the diver is prone to certain types of unique injury that are not found elsewhere.

Suction/entrapment injury is something especially to be guarded against. Working in or near an opening in a ship’s hull, a caisson which has a lower water level on the side opposite the diver, or a dam can be causative of this type of mishap. Divers often refer to this type of situation as being trapped by “heavy water”.

To avoid dangerous situations where the diver’s arm, leg, or whole body may be sucked into an opening such as a tunnel or pipe, strict precautions must be taken to tag out pipe valves and flood gates on dams so that they cannot be opened while the diver is in the water near them. The same is true of pumps and piping within ships that the diver is working on.

Injury can include oedema and hypoxia of an entrapped limb sufficient to cause muscle necrosis, permanent nerve damage, or even loss of the entire limb, or it may occasion gross crushing of a portion of the body or the whole body so as to cause death from simple massive trauma. Entrapment in cold water for a long period of time may cause the diver to die of exposure. If the diver is using scuba gear, he may run out of air and drown before his release can be effected, unless additional scuba tanks can be provided.

Propeller injuries are straightforward and must be guarded against by tagging out a ship’s main propulsion machinery while the diver is in the water. It must be remembered, however, that steam turbine-powered ships, when in port, are continuously turning over their screws very slowly, using their jacking gear to avoid cooling and distortion of the turbine blades. Thus the diver, when working on such a blade (trying to clear it from entangled cables, for example), must be aware that the turning blade must be avoided as it approaches a narrow spot close to the hull.

Whole-body squeeze is a unique injury which can occur to deep sea divers using the classical copper helmet mated to the flexible rubberized suit. If there is no check valve or non-return valve where the air pipe connects to the helmet, cutting the air line at the surface will cause an immediate relative vacuum within the helmet, which can draw the entire body into the helmet. The effects of this can be instant and devastating. For example, at a depth of 10 m, about 12 tons of force is exerted on the soft part of the diver’s dress. This force will drive his body into the helmet if pressurization of the helmet is lost. A similar effect may be produced if the diver fails unexpectedly and fails to turn on compensating air. This can produce severe injury or death if it occurs near the surface, as a 10-metre fall from the surface will halve the volume of the dress. A similar fall occurring between 40 and 50 m will change the suit volume only about 17%. These volume changes are in accordance with Boyle’s Law.

Caisson and tunnel workers

Tunnel workers are subject to the usual types of accidents seen in heavy construction, with the additional problem of a higher incidence of falls and injuries from cave-ins. It must be stressed that an injured compressed-air worker who may have broken ribs should be suspected of having a pneumothorax until proven otherwise and therefore great care must be taken in decompressing such a patient. If a pneumothorax is present, it must be relieved at pressure in the working chamber before decompression is attempted.

Noise

Noise damage to compressed-air workers may be severe, as air motors, pneumatic hammers and drills are never properly equipped with silencers. Noise levels in caissons and tunnels have been measured at over 125 dB. These levels are physically painful, as well as causative of permanent damage to the inner ear. Echo within the confines of a tunnel or caisson exacerbates the problem.

Many compressed-air workers balk at wearing ear protection, saying that blocking the sound of an approaching muck train would be dangerous. There is little foundation for this belief, as hearing protection at best only attenuates sound but does not eliminate it. Furthermore, not only is a moving muck train not “silent” to a protected worker, but it also gives other cues such as moving shadows and vibration in the ground. A real concern is complete hermetic occlusion of the auditory meatus provided by a tightly fitting ear muff or protector. If air is not admitted to the external auditory canal during compression, external ear squeeze may result as the ear drum is forced outward by air entering the middle ear via the Eustachian tube. The usual sound protective ear muff is usually not completely air tight, however. During compression, which lasts only a tiny fraction of the total shift time, the muff can be slightly loosened should pressure equalization prove a problem. Formed fibre ear plugs which can be moulded to fit in the external canal provide some protection and are not air tight.

The goal is to avoid a time weighted average noise level of higher than 85 dBA. All compressed-air workers should have pre-employment base line audiograms so that auditory losses which may result from the high-noise environment can be monitored.

Hyperbaric chambers and decompression locks can be equipped with efficient silencers on the air supply pipe entering the chamber. It is important that this be insisted on, as otherwise the workers will be considerably bothered by the ventilation noise and may neglect to ventilate the chamber adequately. A continuous vent can be maintained with a silenced air supply producing no more than 75dB, about the noise level in an average office.

Fire

Fire is always of great concern in compressed-air tunnel work and in clinical hyperbaric chamber operations. One can be lulled into a false sense of security when working in a steel-walled caisson which has a steel roof and a floor consisting only of unburnable wet muck. However, even in these circumstances, an electrical fire can burn insulation, which will prove highly toxic and can kill or incapacitate a work crew very quickly. In tunnels which are driven using wooden lagging before the concrete is poured, the danger is even greater. In some tunnels, hydraulic oil and straw used for caulking can furnish additional fuel.

Fire under hyperbaric conditions is always more intense because there is more oxygen available to support combustion. A rise from 21% to 28% in the oxygen percentage will double the burning rate. As the pressure is increased, the amount of oxygen available to burn increases The increase is equal to the percentage of oxygen available multiplied by the number of atmospheres in absolute terms. For example, at a pressure of 4 ATA (equal to 30 m of sea water), the effective oxygen percentage would be 84% in compressed-air. However, it must be remembered that even though burning is very much accelerated under such conditions, it is not the same as the speed of burning in 84% oxygen at one atmosphere. The reason for this is that the nitrogen present in the atmosphere has a certain quenching effect. Acetylene cannot be used at pressures over one bar because of its explosive properties. However, other torch gases and oxygen can be used for cutting steel. This has been done safely at pressures up to 3 bar. Under such circumstances, however, scrupulous care must be exercised and someone must stand by with a fire hose to immediately quench any fire which might start, should an errant spark come in contact with something combustible.

Fire requires three components to be present: fuel, oxygen and an ignition source. If any one of these three factors is absent, fire will not occur. Under hyperbaric conditions, it is almost impossible to remove oxygen unless the piece of equipment in question can be inserted into the environment by filling it or surrounding it with nitrogen. If fuel cannot be removed, an ignition source must be avoided. In clinical hyperbaric work, meticulous care is taken to prevent the oxygen percentage in the multiplace chamber from rising above 23%. In addition, all electrical equipment within the chamber must be intrinsically safe, with no possibility of producing an arc. Personnel in the chamber should wear cotton clothing which has been treated with flame retardant. A water-deluge system must be in place, as well as a hand-held fire hose independently actuated. If a fire occurs in a multiplace clinical hyperbaric chamber, there is no immediate escape and so the fire must be fought with a hand-held hose and with the deluge system.

In monoplace chambers pressurized with 100% oxygen, a fire will be instantly fatal to any occupant. The human body itself supports combustion in 100% oxygen, especially at pressure. For this reason, plain cotton clothing is worn by the patient in the monoplace chamber to avoid static sparks which could be produced by synthetic materials. There is no need to fireproof this clothing, however, as if a fire should occur, the clothing would afford no protection. The only method for avoiding fires in the monoplace oxygen-filled chamber is to completely avoid any source of ignition.

When dealing with high pressure oxygen, at pressures over 10 kg/cm2 gauge, adiabatic heating must be recognized as a possible source of ignition. If oxygen at a pressure of 150 kg/cm2 is suddenly admitted to a manifold via a quick-opening ball valve, the oxygen may “diesel” if even a tiny amount of dirt is present. This can produce a violent explosion. Such accidents have occurred and for this reason, quick-opening ball valves should never be used in high pressure oxygen systems.

Psychosocial Factors and Organizational Management

The term organization is often used in a broad sense, which is not so strange because the phenomenon of an “organization” has many aspects. It can be said that studying organizations makes up an entire problem area of its own, with no natural location within any specific academic discipline. Certainly the concept of organization has obtained a central position within what is called management science—which, in some countries, is a subject in its own right within the field of business studies. But in a number of other subject areas, among them occupational safety and health, there has also been reason to ponder why one is considering organizational theory and to determine which aspects of organization to embrace in research analyses.

The organization is not just of importance to company management, but is also of great significance for each person’s work situation, both in health terms and in relation to his or her short- and long-term opportunities for making an effective contribution to work. Thus, it is of key importance for specialists in the field of occupational safety and health to be acquainted with the theorizing, conceptualization and forms of thinking about social reality to which the terms organization and organizational development or change refer.

Organizational arrangements have consequences for social relationships that exist amongst the people who work in the organization. Organizational arrangements are conceived of and intended to achieve certain social relations at work. A multiplicity of studies on psychosocial aspects of working life have affirmed that the form of an organization “breeds” social relations. The choice between alternative organizational structures is governed by a variety of considerations, some of which have their origins in a particular approach to management and organizational coordination. One form can be based on the view that effective organizational management is achieved when specific social interactions between the organization’s members are enabled. The choice of the structural form in an organization is made on the basis of the way in which people are intended to be linked together to establish organizationally effective interdependent relations; or, as theorists of business administration tend to express the idea: “how the growth of critical combinations is facilitated”.

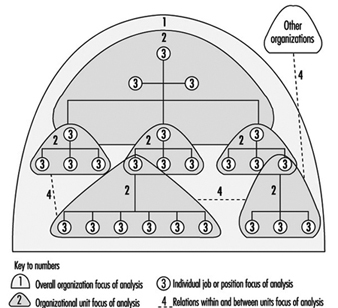

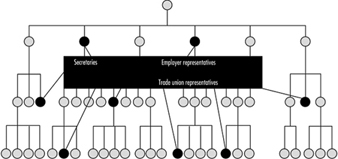

One of the prominent members of the “human relations school”, Rensis Likert (1961, 1967) has provided an enduring idea on how hierarchical “subsystems” in a complex organizational structure ideally should be linked together. Likert pointed to the importance of unity and solidarity among members of an organization. Here, the job supervisor/manager has a dual task:

- to maintain unity and create a sense of belonging within a work group, and

- to represent his or her work group in meetings with superior and parallel managerial staff. In this way the bonds between the hierarchical levels are reinforced.

Likert’s “linking pin model” is shown in figure 1. Likert employed the analogy of the family to characterize desirable social interaction between different work units, which he conceived as functioning as “organizational families”. He was convinced that the provision by management of scope and encouragement for the strengthening of personal relations between workers at different levels was a powerful means for increasing organizational effectiveness and uniting personnel behind the goals of the company. Likert’s model is an attempt to achieve “a regularity of practice” of some kind, which would further reinforce the organizational structure laid down by management. From around the beginning of the 1990s his model has acquired increasing relevance. Likert’s model may be regarded as an example of a recommended structure.

Figure 1. Likert’s linking pin model

One way of using the term organization is with the focus on the human beings’ competence; the organization in that sense is the total combination of competences and, if one wants to go a bit further, their synergetic effects. Another and opposite perspective places its focus on the coordination of people’s activities needed to fulfil a set of goals of a business. We can call that the “organizational arrangement” which is decided upon on an agreed basis. In this chapter on organizational theory the presentation has its point of departure in organizational arrangement, and the members or workers participating in this arrangement are looked at from an occupational health perspective.

Structure as a Basic Concept in Organizational Theory

Structure is a common term within organization theory, referring to the form of organizational arrangement intended to bring a goal effectiveness. Business activities in working life can be analysed from a structural perspective. The structural approach has for long been the most popular, and has contributed most—quantitatively speaking—to the knowledge we have on organizations. (At the same time, members of a younger generation of organization researchers have expressed a series of misgivings concerning the value of this approach (Alvesson 1989; Morgan 1986)).

When adopting a structural perspective it is taken more or less for granted that there exists an agreed order (structure) to the form in which a set of activities is carried out. On the basis of this fundamental assumption, the organizational issue posed becomes one of the specific appearance of this form. In how much detail and in which ways have the tasks of persons in different job positions been described in formally issued, official documents? What rules apply to people in managerial positions? Information on the organizational pattern, the body of regulations and specified relations is available in documents such as instructions for management and job descriptions.

A second issue raised is how activities are organized and patterned in practice: what regularities actually exist, and what is the nature of relations between people? Raising this question in itself implies that a complete correspondence between formally decreed and practised forms of activities should not be expected. There are several reasons for this. Naturally, not all phases of work can be covered by a prescribed body of rules. Also, defining operations as they should be carried out will often not be adequate to describe the actual activities of workers and their interaction with each other because:

- The official structure will not necessarily be completely detailed, thus providing different degrees of scope for coordination/cooperation in practice.

- The normative (specified) nature of organizational structure will not match exactly the forms that members of the organization consider to be effective for activities.

- An organization’s stated norms or rules provide a greater or lesser degree of motivation.

- The normative structure itself will have varying degrees of visibility within the organization, depending on the access of members of the organization to relevant information.

In practical terms, it is probably impossible for the scope of any norms which are developed to describe adequately the normal routines that occur. Defined norms simply cannot encompass the full range of practice and relations between human beings. The adequacy of the norms will be dependent on the level of detail in which the official structure is expressed. It is interesting and important in the assessment of organizations and for any preventive programmes to establish the extent of the correspondence between the norms and the practices of organizational activities.

The extent of the contrast between norms and practices (objective and subjective definitions of organizational structure) is important as is the difference between the organizational structure that is perceived by an “investigator” and the individual organizational member’s image or perception of it. Not only is a lack of correspondence between the two of great intellectual interest, it can also constitute a handicap for the individual in the organization in that he or she may have far too inadequate a picture of the organization to be able to protect and/or promote his or her own interests.

Some Basic Structural Dimensions

There has been a long succession of ideas and principles concerning the management of organizations, each in turn striving for something new. Despite this, however, it remains the case that the official organizational structure generally stipulates a form of hierarchical order and a division of responsibilities.Thus, it specifies major aspects of vertical integration and functional responsibility or authorization.

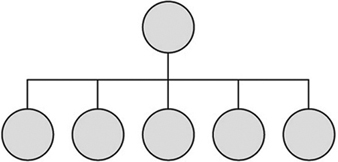

Figure 2. The classical original organizational form

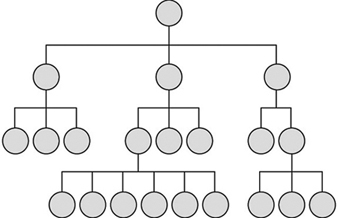

We encounter the idea of vertical influence most readily in its simplest, classical original form (see Figure 2). The organization comprises one superior and a number of subordinates, a number small enough for the superior to exercise direct control. The developed classical form (see figure 3) demonstrates how a complex organizational structure can be built up from small hierarchical systems (see figure 1). This common, extended form of the classical organization, however, does not necessarily specify the nature of horizontal interaction between people in non-management positions.

Figure 3. The extended classical form

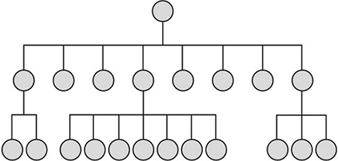

An organizational structure mostly consists of managerial layers (i.e., a “triangular” structure, with a few or several layers descending from the apex), and there is almost always a more or less accentuated hierarchically ordered form of organization desired. The basic principle is that of “unity of command” (Alvesson 1989): a “scalar” chain of authority is created, and applied more or less strictly according to the nature of the organizational structure selected. There may be long vertical channels of influence, forcing personnel to cope with the inconveniences of lengthy chains of command and indirect paths of communication when they wish to reach a decision-maker. Or, when there are only a few management layers (i.e., the organizational structure is flat—see Figure 4), this indicates a preference on the part of top management to de-emphasize the supervisor-subordinate relationship. The distance between top management and employees is shorter, and lines of contact are more direct. At the same time, however, each manager will have a relatively large number of subordinates—in fact, sometimes so many that he or she cannot usually exercise direct control over personnel. Greater scope is thereby given for horizontal interaction, which becomes a necessity for operational effectiveness.

Figure 4. The flat organization

In a flat organizational structure, the norms for vertical influence are only crudely specified in a simple organizational chart. The chart thus has to be supplemented by instructions for managers and by detailed job instructions.

Hierarchical structures may be viewed as a normative means of control, which in turn may be characterized as offering minimum liability to members of the organization. Within this framework there is a more or less generously allocated amount of scope for individual influence and action, depending on what has been decided in relation to the decentralization of decision-making, delegation of tasks, temporary coordinating groups, and the structure of budgetary responsibilities. Where there is less generous scope for influence and action, there will be correspondingly smaller margin for error on the part of the individual. The degree of latitude can usually only be guessed at from the content of the official documents referred to.

In addition to the hierarchical order (vertical influence), the official organizational structure specifies some (normative) form of division of responsibility and thereby functional authority. It might be said that the art of leading an organization as a whole is largely a matter of structuring all its activities in such a way that the combination of different functions arrived at has the greatest conceivable external impact. The names of the different parts (the functions) of the structure specify, albeit only as an outline, how management has conceived the breakdown into various sections of activities and how these shall then be combined and accounted for. From this we can also trace the demands placed on managers’ functional authority.

Modifying the Organizational Structures

There are many variants on how an organization as a whole can be built up. One of the basic issues is how core activities (the production of goods or services) are to be combined with other necessary operational elements, including personnel management, information, administration, maintenance, marketing and so on. One alternative is to place major departments for administration, personnel, company finances and so on alongside production units (a functional or “staff” organization). Behind such an arrangement lies management’s interest in personnel, within their specialized areas, developing a broad range of skills so that they can provide production units with assistance and support, reduce the burden upon them and promote their development.

An alternative to “administration parallel” is to staff production units with people possessing the required specialized administrative skills. In this way cooperation across specialized administrative boundaries can be brought about, thus benefiting the production unit in question. Additional alternative structures are possible, based on ideas concerning functional combinations which would promote cooperative working within organizations. Often organizations are required to respond to change in the operating environment, and hence a change in structure occurs. The transition from one organizational structure to another can involve drastic changes in desired forms of interaction and cooperation. These need not affect everyone in the organization; often they are imperceptible to the occupiers of certain job positions. It is important to take the changes into account in any analysis of organizational structures.

Identifying types of existing structures has become a major research task for many organization theorists in the business administration field (see, for example, Mintzberg 1983; Miller and Mintzberg 1983), the idea being that it would be of benefit if researchers could recognize the nature of organizations and place them in easily identifiable categories. By contrast, other researchers have used empirical data (data based on observations of organizational structures) to demonstrate that limiting description to such strict typologies obscures the nuances of reality (Alvesson 1989). In their view, it is relevant to learn from the individual case rather than simply to generalize immediately to an existing typology. A researcher of occupational health should prefer the latter reality-based approach as it contributes to a better, more adequate understanding of the situational conditions in which the individual workers are involved.

Parallel Structures

Alongside its basic organizational structure (which specifies vertical influence and the functional distribution for core activities), an organization may also possess certain ad hoc structures, which may be set up for either a definite or indefinite time period. These are often called “parallel structures”. They can be instituted for a variety of reasons, such as to further reinforce the competitiveness of the company (primarily serve the company’s interests), as is the case with networking, or to strengthen the rights of employees (primarily serve the interests of employees), such as mechanisms for surveillance (e.g., health and safety committees).

As surveillance of the work environment has as its primary function to promote the safety interests of employees, it is frequently organized in a rather more permanent parallel structure. Such structures exist in many countries, often with operational procedures that are laid down by national legislation (see the chapter Labour Relations and Human Resources Management).

Networking

In modern corporate management, network is a term that has acquired a specialized usage. Creating a network means organizing circles of intermediate-level managers and key personnel from diverse parts of an organization for a specific purpose. The task of the network may be to promote development (e.g., that of secretarial positions throughout the company), provide training (e.g., personnel at all retail outlets), or effect rationalization (e.g., all the company’s internal order routines). Typically, a networking task involves improving corporate operations in some concrete respect, such that the entire company is permeated by the improvement.

Compared with Likert’s linking pin model, which aims to promote vertical as well as horizontal interaction within and between layers in the hierarchical structure, the point of a network is to tie people together in different constellations than those offered by the base structure (but, note, for no other reason than that of serving the interests of the company).

Networking is initiated by management to counter—but not dismantle—the established hierarchical structure (with its functional divisions) which has emerged as being far too sluggish in response to new demands from the environment. Creating a network can be a better option than embarking on an arduous process of changing or restructuring the entire organization. According to Charan (1991), the key to effective networking is that top management gets the network working and selects its members (who should be highly motivated, energetic and committed, quick and effective, and with an ability to easily disseminate information to other employees). Top management should also keep a watchful eye on continued activities within the network. In this sense, networking is a “top-down” approach. With the sanction of management and funds at its disposal, a network can become a powerful structure which cuts across the base organization.

Networking

One example of networking is the recent effort aimed at improving the general level of competence of operators which took place in a Volvo firm. Management initiated a network whose members could work out a system of tasks ordered according to the level of difficulty. A corresponding training programme guaranteed the workers a possibility of following a "career ladder" including a corresponding wage system. The members of the network were selected from among experienced employees from different parts of the plant and at different levels. Because the proposed system was perceived as an innovation, the collaboration in the network became highly motivating and the plan was realized in the shortest possible time.

Implications for Health and Safety

The occupational health specialist has much to gain by asking how much of the interaction between people in the organization rests on the basic organizational structure and how much on the parallel structures that have been set up. In which does the individual actively take part? What is demanded from the individual in terms of effort and loyalty? How does this affect encounters with and cooperation between colleagues, work mates, managers and other active participants in formal contexts?

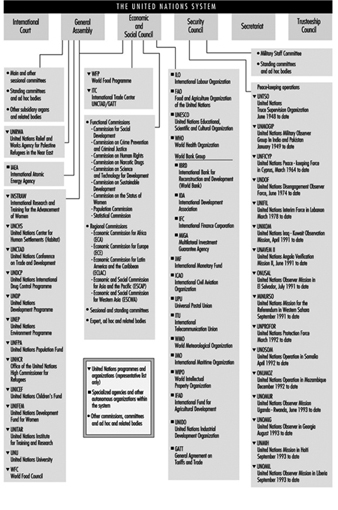

To the occupational health specialist concerned with psychosocial issues it is important to be aware that there is always some person(s) (from outside or inside the organization) who has taken on or been allocated the task of designing the set of normative prescriptions for activities. These “organizational creators” do not act alone but are assisted within the organization by loyal supporters of the structure they create. Some of the supporters are active participants in the creative process who use and further develop the principles. Others are the representatives or “mouthpieces” of personnel, either collectively or of specific groups (see figure 5). Moreover, there is also a large group of personnel who can be characterized as administrators of the prescribed form of activities but who have no say in its design or the method of its implementation.

Figure 5. The organization of occupational safety - a parallel structure

Organizational Change

By studying organizational change we adopt a process perspective. The concept organizational change covers everything from a change in the total macrostructure of a company to alterations in work allocation—coordination of activity in precisely defined smaller units; it may involve changes in administration or in production. In one or another way the issue is to rearrange the work-based relations between employees.

Organizational changes will have implications for the health and well-being of those in the organization. The most easily observed dimensions of health are in the psychosocial domain. We can state that organizational change is very demanding for many employees. It will be a positive challenge to many individuals, and periods of lassitude, tiredness and irritation are unavoidable. The important thing for those responsible for occupational health is to prevent such feelings of lassitude from becoming permanent and to turn them into something positive. Attention must be paid to the more enduring attitudes to job quality and the feedback one gets in the form of one’s own competence and personal development; the social satisfactions (of contacts, collaboration, “belongingness”, team spirit, cohesiveness) and finally the emotions (security, anxiety, stress and strain) deriving from these conditions. The success of an organizational change should be assessed by taking into consideration these aspects of job satisfaction.

A common misconception which may hinder the ability to respond positively to organizational change is that normative structures are just formalities which have no relevance to how people really act or how they perceive the state of affairs they encounter. People who are labouring under this misconception believe that what is important is “the order in practice”. They concentrate on how people actually act in “reality”. Sometimes this point of view may seem convincing, especially in the case of those organizations where structural change has not been implemented for a considerable period of time and where people have got used to the existing organizational system. Employees have become accustomed to an accepted, tried and tested order. In these situations, they do not reflect upon whether it is normative or just operates in practice, and do not care very much whether their own “image” of the organization corresponds with the official one.

On the other hand, it should also be noted that the normative descriptions may seem to provide a more accurate picture of an organization’s reality than is the case. Simply because such descriptions are documented in writing and have received an official stamp does not mean that they are an accurate representation of the organization in practice. Reality can differ greatly, as for example when normative organizational descriptions are so out of date as to have lost current relevance.

To optimize effectiveness in responding to change, one has to sort out carefully the norms and the practices of the organization undergoing change. That formally laid down norms for operations affect and intervene in interactions between people, first becomes apparent to many when they have personally witnessed or been drawn into structural change. Studying such changes requires a process perspective on the organization.

A process perspective includes questions of the type:

- How in reality do people interact within an organization that has been structured according to a certain principle or model?

- How do people react to a prescribed formal order for activities and how do they handle this?

- How do people react to a new order, proposed or already decided upon, and how do they handle this?

The point is to obtain an overall picture of how it is envisaged that workers shall relate to each other, the ways in which this happens in practice, and the nature of the state of tension between the official order and the order in practice.

The incompatibility between the description of organizations and their reality is one of the indications that there is no organizational model which is always “the best” for describing a reality. The structure selected as a model is an attempt (made with a greater or lesser degree of success) to adapt activities of the problems which management finds it most urgent to solve at a particular point in time when it is clear that an organization must undergo change.

The reason for effecting a transition from one structure to another may be the result of a variety of causes, such as changes in the skills of personnel available, the need for new systems of remuneration, or the requirement that the influence of a particular section of functions of the organization should be expanded—or contracted. One or several strategic motives can lie behind changes in the structure of an organization. Often the driving force behind change is simply that the need is so great, the goal has become one of organizational survival. Sometimes the issue is ease of survival and sometimes of survival itself. In some cases of structural change, employees are involved to only a limited extent, sometimes not at all. The consequences of change can be favourable for some, unfavourable for others. One occasionally encounters instances where organizational structures are changed primarily for the purpose of promoting employees’ occupational health and safety (Westlander 1991).

The Concept of Work Organization

Until now we have focused on the organization as a whole. We can also restrict our unit of analysis to the job content of the individual worker and the nature of his or her collaboration with colleagues. The most common term we find used for this is work organization. This too is a term which is employed in several disciplines and within various research approaches.

First, for example, the concept of work organization is to be found in the pure ergonomic occupational research tradition which considers the way in which equipment and people are adapted to each other at work. With respect to human beings, what is central is how they react to and cope with the equipment. In terms of strain and effectiveness, the amount of time spent at work is also important. Such time aspects include how long the work should go on, during which periods of the day or night, with what degree of regularity, and which time-related opportunities for recovery are offered in the form of the scheduling of breaks and the availability of lengthier periods of rest or time off. These time conditions must be organized by management. Thus, such conditions should be regarded as organizational factors within the field of ergonomic research—and as very important ones. It may be said that the time devoted to the work task can moderate the relationship between equipment and worker with respect to health effects.

But there are also wider ergonomic approaches: analyses are extended to take into account the work situation in which the equipment is employed. Here it is a question of the work situation and the worker being well adapted to each other. In such cases, it is the equipment plus a series of work organizational factors (such as job content, kinds and composition of tasks, responsibilities, forms of cooperation, forms of supervision, time devoted in all its aspects) which make up the complex situation which the worker reacts to, copes with and acts within.

Such work organizational factors are taken account of in broader ergonomic analyses; ergonomics has often included consideration of the type of work psychology which focuses on the job content of the individual (kinds and composition of tasks) plus other related demands. These are regarded as operating in parallel with physical conditions. In this way, it becomes the task of the researcher to adopt a position on whether and how the physical and work organizational conditions with which the individual is regularly confronted contribute to aspects of ill-health (e.g., to stress and strain). To isolate cause and effect is a considerably more difficult undertaking than is the case when a narrow ergonomic approach is adopted.