Case Study: Exposure Standards in Russia

Comparison of the Philosophical Bases of Maximum Allowable Concentrations (MACs) and Threshold Limit Values (TLVs)

Rapid development of chemistry and wide usage of chemical products require specific toxicological studies and hazards evaluation with regard to long-term and combined effects of chemical substances. The setting of standards for chemicals in the working environment is being conducted by occupational hygienists in many countries of the world. Experience on the matter has been accumulated in international and multilateral organizations such as the International Labour Organization, the World Health Organization, the United Nations Environment Programme, the Food and Agriculture Organization and the European Union.

Much has been done in this field by Russian and American scientists. In 1922 studies were launched in Russia to set up standards for chemicals in the air of indoor work areas, and the first maximum allowable concentration (MAC) value for sulphur-containing gas was adopted. By 1930 only 12 MAC values were established, whereas by 1960 their number reached 181.

The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) started its work in 1938, and the first threshold limit values (TLVs) list was published in 1946 for 144 substances. The TLVs are to be interpreted and used only by the specialists in this field. If a TLV has been included in the safety standards (the so-called standards of national consensus) and the federal standards, it becomes legal.

At present more than 1,500 MAC values have been adopted for workplace air in Russia. More than 550 TLVs for chemical substances have been recommended in the United States.

Analysis of hygienic standards made in 1980–81 showed that 220 chemicals of the MAC list (Russia) and the TLV list (United States) had the following differences: from two- to fivefold differences were found in 48 substances (22%), 42 substances had five- to ten-fold differences, and 69% substances (31%) had more than ten-fold differences. Ten per cent of the recommended TLVs were 50 times higher than the MAC values for the same substances. The MAC values, in turn, were higher than the TLVs for 16 substances.

The largest divergence of standards occurs in the class of chlorinated hydrocarbons. Analysis of the TLV list adopted in 1989–90 showed a trend toward a reduction of the earlier recommended TLVs compared with the MAC values for chlorinated hydrocarbons and some solvents. Differences among the TLVs and the MACs for the majority of metal aerosols, metalloids, and their compounds were insignificant. The divergences for irritant gases were also slight. The TLVs for lead, manganese and tellurium compared with their MAC analogues disagreed 15, 16 and 10 times, respectively. The differences for acetic aldehyde and formaldehyde were the most extreme—36 and 6 times, respectively. In general, the MAC values adopted in Russia are lower than the TLVs recommended in the United States.

These divergences are explained by the principles used in the development of hygienic standards in the two countries and by the way of these standards are applied to protect workers’ health.

A MAC is a hygienic standard used in Russia to denote a concentration of a harmful substance in the air of the workplace which will not cause, in the course of work for eight hours daily or for any other period of time (but not more than 41 hours per week throughout the working life of an individual), any disease or deviation in the health status as detectable by the available methods of investigation, during the working life or during the subsequent life of the present and next generations. Thus, the concept used in defining the MAC does not allow for any adverse effect on a worker or his or her progeny. The MAC is a safe concentration.

A TLV is the concentration (in air) of a material to which most workers can be exposed daily without adverse effect. These values are established (and revised annually) by the ACGIH and are time-weighted concentrations for a seven- or eight-hour workday and 40-hour workweek. For most materials the value may be exceeded, to a certain extent, provided there are compensatory periods of exposure below the value during the workday (or in some cases the week). For a few materials (mainly those that produce a rapid response) the limit is given as ceiling concentration (i.e., a maximum allowable concentration) that should never be exceeded. The ACGIH states that TLVs should be used as guides in the control of health hazards, and are not fine lines between safe and dangerous concentrations, nor are they a relative index of toxicity.

The TLV definition also contains the principle of inadmissibility of harmful impact. However, it does not cover all of the working population, and it is admitted that a small percentage of workers may manifest health changes or even occupational pathologies. Thus TLVs are not safe for all workers.

According to ILO and WHO experts, these divergences are the result of different scientific approaches to a number of interrelated factors including the definition of an adverse health effect. Therefore, different initial approaches for the control of chemical hazards lead to different methodological principles, essential points of which are presented below.

The main principles of setting hygienic standards for dangerous substances in the air of workplaces in Russia compared with those in the United States are summarized in table 1. Of special importance is the theoretical concept of the threshold, the basic difference between the Russian and the American specialists that underlies their approaches to setting standards. Russia accepts the concept of a threshold for all types of dangerous effects of chemical substances.

Table 1. A comparison of some ideological bases for Russian and American standards

|

Russia (MACs) |

United States (TLVs) |

|

Threshold nature of all kinds of adverse effects. Changes of specific and non-specific factors regarding the criteria of harmful impact are evaluated. |

No recognition of threshold for mutagens and some carcinogens. Changes of specific and non-specific factors depending on “dose-effect ”and “dose-response” relationship are evaluated. |

|

Priority of medical and biological factors over technological and economic criteria. |

Technological and economic criteria prevail. |

|

Prospective toxicological assessment and interpretation of standards before the commercialization of chemical products. |

Retrospective setting of standards. |

However, the recognition of a threshold for some types of effects requires the distinction between injurious and non-injurious effects produced by chemical substances. Consequently, the threshold of unhealthy effects established in Russia is the minimal concentration (dose) of a chemical that causes changes beyond the limits of physiological adaptive responses or produces latent (temporarily compensated) pathologies. In addition, various statistical, metabolic, and toxico-kinetic criteria of adverse effects of chemicals are used to differentiate between the processes of physiological adaptation and pathological compensation. Pathomorphological changes and narcotic symptoms of earliest impairment have been suggested in the United States for the identification of injurious and non-injurious effects. It means that more sensitive methods have been chosen for the toxicity evaluation in Russia than those in the United States. This, therefore, explains the generally lower levels of MACs compared to TLVs. When the detection criteria for injurious and non-injurious effects of chemicals are close or practically coincide, as in the case of irritant gases, the differences in standards are not so significant.

The evolution of toxicology has put into practice new methods for the identification of minor changes in tissues. These are enzyme induction in the smooth endoplastic reticular hepatic tissue and reversible hypertrophy of the liver. These changes may appear after exposure to low concentrations of many chemical substances. Some researchers consider these to be adaptive reactions, while others interpret them as early impairments. Today, one of the most difficult tasks of toxicology is obtaining data that show whether enzyme disturbances, nervous system disorders and changes in behavioural responses are the result of deteriorated physiological functions. This would make it possible to predict more serious and/or irreversible impairments in case of long-term exposure to dangerous substances.

Special emphasis is placed on the differences in the sensitivity of methods used for the establishment of MACs and TLVs. Very sensitive methods of conditioned reflexes applied to studies of the nervous system in Russia have been found to be the main cause of divergences between the MACs and the TLVs. However, the use of this method in the process of hygienic standardization is not obligatory. Numerous methods of different sensitivities are normally used for the developing of a hygienic standard.

A great number of studies conducted in the United States in connection with the setting-up of exposure limits are aimed at examining the transformation of industrial compounds in the human body (routes of exposure, circulation, metabolism, removal, etc.). Methods of chemical analysis used to establish the values of TLVs and MACs also cause divergences due to their different selectivities, accuracies and sensitivities. An important element usually taken into consideration by OSHA in the standardization process in the United States is the “technical attainability” of a standard by industry. As a result, some standards are recommended on a basis of the lowest presently existing concentrations.

MAC values in Russia are established on a basis of the prevalence of medico-biological characteristics, whereas the technological attainability of a standard is practically ignored. This partly explains lower MAC values for some chemical substances.

In Russia MAC values are assessed in toxicological studies before a substance is authorized for industrial use. A tentative safe exposure level is established during the laboratory synthesis of a chemical. The MAC value is established after animal experiments, at the design stage of the industrial process. The correction of the MAC value is carried out after evaluation of working conditions and workers’ health when the substance is used in industry. Most of the safe levels of exposure in Russia have been recommended after experiments on animals.

In the United States a final standard is established after a chemical substance has been introduced in industry, because the values of permissible levels of exposure are based on the assessment of health. As long as the differences of principle between the MACs and the TLVs remain, it is unlikely to expect the convergence of these standards in the near future. However, there is a trend towards the reduction of some TLVs that makes this not so impossible as it may seem.

Legislation Guaranteeing Benefits for Workers in China

The occupational safety and health of workers has been an important aspect of legislation laid down in the form of the Labour Law promulgated in July 1994. To urge enterprises into the market system, and in the meantime to protect the rights of labourers, in-depth reforms in the system of labour contracts and wage distribution and in social security have been major priorities in the government agenda. Establishing a uniform welfare umbrella for all workers regardless of the ownership of the enterprises is one of the goals, which also include unemployment coverage, retirement pension systems, and occupational disease and injuries compensation insurance. The Labour Law requires that all employers pay a social security contribution for their workers. Part of the legislation, the draft of the Occupational Disease Prevention and Control Law, will be an area of the Labour Law to which major attention has been devoted in order to regulate the behaviour and define the responsibilities of employers in controlling occupational hazards, while at the same time giving more rights to workers in protecting their own health.

Cooperation Between Governmental Agencies and the All-China Federation of Trade Unions in Policy Making and Legislation Enforcement

The Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), the Ministry of Labour (MOL), and the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) have a long history of cooperation. Many important policies and activities have resulted from their joint efforts.

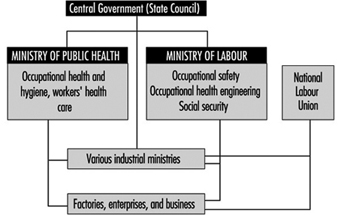

The current division of responsibility between the MOPH and the MOL in occupational safety and health is as follows:

- From the preventive medical point of view, the MOPH oversees industrial hygiene and occupational health, enforcing national health inspection.

- The focus of the MOL is on engineering the control of occupational hazards and on the organization of labour, as well as overseeing occupational safety and health and enforcing national labour inspection (figure 1) (MOPH and MOL 1986).

Figure 1. Governmental organization and division of responsibility for occupational health and safety

It is difficult to draw a line between the responsibilities of the MOPH and the MOL. It is expected that further cooperation will focus on enhancing enforcement of occupational safety and health regulations.

The ACFTU has been increasingly involved in safeguarding workers’ rights. One of the important tasks of the ACFTU is to promote the establishment of trade unions in foreign-funded enterprises. Only 12% of overseas-funded enterprises have established unions.

Occupational Health and Safety: The European Union

The European Union (EU) today exercises a major influence on worldwide health and safety law and policy. In 1995, the Union comprised the following Member States: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. It will probably expand in years to come.

The forerunner of the Union, the European Community, was created in the 1950s by three treaties: The European Coal and Steel Community Treaty (ECSC) signed in Paris in 1951, and the European Economic Community (EEC) and European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC) Treaties signed in Rome in 1957. The European Union was formed with the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty (concluded in 1989) on 1 January 1992.

The Community has four institutions, namely, the Commission, the Council, the Parliament and the European Court of Justice. They derive their powers from the treaties.

The Structures

The Commission

The Commission is the Community’s executive body. It is responsible for initiating, proposing and implementing Community policy, and if a Member State fails to fulfil its obligations under the treaties, the Commission can take proceedings against that Member State in the European Court of Justice.

It is composed of seventeen members appointed by the governments of Member States for a renewable four-year period. Each Commissioner is responsible for a portfolio and has authority over one or more Directorates General. One such Directorate General, DG V, is concerned with Employment, Industrial Relations and Social Affairs, and it is from within this Directorate General (DG V/F) that health and safety and public health policies are both initiated and proposed. The Commission is assisted in its health and safety law and policy-making role by the Advisory Committee on Safety, Hygiene and Health Protection at Work and the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Advisory Committee on Safety, Hygiene and Health Protection at Work

The Advisory Committee was established in 1974 and is chaired by the Commissioner responsible for the Directorate-General for Employment, Industrial Relations and Social Affairs. It consists of 96 full members: two representatives each of government, trade unions, and employers’ organizations from each Member State.

The role of the Advisory Committee is to “assist the Commission in the preparation and implementation of activities in the fields of safety, hygiene and health protection at work”. Because of its constitution and membership, the Advisory Committee is much more important and pro-active than its title suggests, so that, over the years, it has had a significant influence on strategic policy development, acting alongside the European Parliament and the Economic and Social Committee. More specifically, the Committee is responsible for the following matters within its general frame of reference:

- conducting exchanges of views and experience regarding existing or planned regulations

- contributing towards the development of a common approach to problems existing in the fields of safety, hygiene and health protection at work and towards the choice of Community priorities as well as measures necessary for implementing them

- drawing the Commission’s attention to areas in which there is an apparent need for the acquisition of new knowledge and for the implementation of appropriate educational and research projects

- defining, within the framework of Community action programmes, and in cooperation with the Mines Safety and Health Commission, (i) the criteria and aims of the campaign against the risk of accidents at work and health hazards within the undertaking; and (ii) methods enabling undertakings and their employees to evaluate and to improve the level of protection

- contributing towards keeping national administrations, trade unions and employers’ organizations informed of Community measures in order to facilitate their cooperation and to encourage initiatives promoted by them aiming at exchanges of experience and at laying down codes of practice

- submitting opinions on proposals for directives and on all measures proposed by the Commission which are of relevance to health and safety at work.

In addition to these functions, the Committee prepares an annual report, which the Commission then forwards to the Council, the Parliament and the Economic and Social Committee.

The Dublin Foundation

The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, located in Dublin, was established in 1975 as a specialized, autonomous Community body. The Foundation is primarily engaged in applied research in the areas of social policy, the application of new technologies, and the improvement and protection of the environment, in an effort to identify, cope with and forestall problems in the working environment.

European Agency for Health and Safety at the Workplace

The European Council has recently established the European Agency for Health and Safety at the Workplace in Bilbao, Spain, which is responsible for collating and disseminating information in its sector of activities. It will also organize training courses, supply technical and scientific support to the Commission and forge close links with specialized national bodies. The agency will also organize a network system with a view to exchanging information and experiences between Member States.

The European Parliament

The European Parliament exercises an increasingly important consultative role during the Community’s legislative process, controls a part of the Community’s budget jointly with the Council, approves Community Association agreements with non-member countries and treaties for the accession of new Member States, and is the Community’s supervisory body.

The Economic and Social Committee

The Economic and Social Committee is an advisory and consultative body which is required to give its opinion on a range of social and vocational issues, including health and safety at work. The Committee draws its membership from three main groups: employers, workers and an independant group comprising members with a wide spectrum of interests including professional, business, farming, the cooperative movement and consumer affairs.

Legal Instruments

There are four main instruments available to the Community legislator. Article 189 of the EEC Treaty as amended provides that “In order to carry out their task and in accordance with the provisions of this Treaty, the European Parliament acting jointly with the Council and the Commission shall make regulations and issue directives, take decisions, make recommendations or deliver opinions.”

Regulations

It is stated that “A regulation shall have general application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.” Regulations are directly enforceable in Member States. There is no need for further implementation. Indeed, it is not permissible for legislatures to consider them with a view to that end. In the field of health and safety at work, regulations are rare and those that have been made are administrative in nature.

Directives and decisions

It is stated that “A directive shall be binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods.” Directives are instructions to Member States to enact laws to achieve an end result. In practice, directives are used mainly to bring about the harmonization or approximation of national laws in accordance with Article 100. They are therefore the most appropriate and commonly used instruments for occupational health and safety matters. In relation to decisions, it is stated that “A decision shall be binding in its entirety upon those to whom it is addressed.”

Recommendations and opinions

Recommendations and opinions have no binding force but are indicative of policy stances.

Policy

The European Communities made a decision in the mid-1980s to press ahead strongly with harmonization measures in the field of health and safety. Various reasons have been put forward to explain the developing importance of this area, of which four may be considered to be significant.

First, it is said that common health and safety standards assist economic integration, since products cannot circulate freely within the Community if prices for similar items differ in various Member States because of variable health and safety costs imposed on business. Second, 10 million people a year are the victims of, and 8,000 people a year die from, workplace accidents (out of a workforce which numbered 138 million people in 1994). These grim statistics give rise to an estimated bill of ECU 26,000 million paid in compensation for occupational accidents and diseases annually, whilst in Britain alone the National Audit Office in their Report Enforcing Health and Safety in the Workplace estimated that the cost of accidents to industry and the taxpayer is £10 billion per year. It is argued that a reduction of the human, social and economic costs of accidents and ill-health borne by this workforce will not only bring about a huge financial saving but will also bring about a significant increase in the quality of life for the whole Community. Third, the introduction of more efficient work practices is said to bring with it increased productivity, lower operational costs and better industrial relations.

Finally, it is argued that the regulation of certain risks, such as those arising from massive explosions, should be harmonized at a supranational level because of the scale of resource costs and (an echo of the first reason canvassed above) because any disparity in the substance and application of such provisions produces distortions of competition and affects product prices.

Much impetus was given to this programme by the campaign organized by the Commission in collaboration with the twelve Member States in the European Year of Health and Safety, which took place during the 12-month period commencing 1 March 1992. This campaign sought to reach the whole of the Community’s working population, particularly targeting high-risk industries and small and medium-sized enterprises.

Each of the founding treaties laid the basis for new health and safety laws. The EEC Treaty, for example, contains two provisions which are, in part at least, devoted to the promotion of health and safety, namely articles 117 and 118.

Community Charter of the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers

To meet the challenge, a comprehensive programme of measures was proposed by the Commission in 1987 and adopted by the Council in the following year. This programme contained a series of health and safety measures grouped under the headings of safety and ergonomics, health and hygiene, information and training, initiatives concerning small and medium enterprises, and social dialogue. Added impetus to these policies was provided by the Community Charter of the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers, adopted in Strasbourg in December 1989 by 11 of the 12 Member States (the United Kingdom abstained).

The Social Charter, as agreed in December 1989, covers 12 categories of “fundamental social rights” among them are several of practical relevance here:

- Improvement of living and working conditions. There should be improvement in working conditions, particularly in terms of limits on working time. particular mention is made of the need for improved conditions for workers on part-time or seasonal contracts and so on.

- Social protection. Workers, including the unemployed, should receive adequate social protection and social security benefits.

- Information, consultation and participation for workers. This should apply especially in multinational companies and in particular at times of restructuring, redundancies or the introduction of new technology.

- Health protection and safety at the workplace.

- Protection of children and adolescents. The minimum employment age should be no lower than the minimum school-leaving age, and in any case not lower than 15 years. The hours which those aged under 18 can work should be limited, and they should not generally work at night.

- Elderly persons. Workers should be assured of resources providing a decent standard of living upon retirement. Others should have sufficient resources and appropriate medical and social assistance.

- Disabled people. All disabled people should have additional help towards social and professional integration.

Member States are given responsibility in accordance with national practices for guaranteeing the rights in the Charter and implementing the necessary measures, and the Commission is asked to submit proposals on areas within its competence.

Since 1989, it has become clear that within the Community as a whole there is much support for the Social Charter. Undoubtedly, Member States are anxious to show that workers, children and older workers should benefit from the Community as well as shareholders and managers.

The 1989 Framework Directive

The principles in the Commission’s health and safety programme were set out in another “Framework Directive” (89/391/EEC) on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work. This makes a significant step forward from the approach witnessed in the earlier “Framework Directive” of 1980. In particular, the 1989 Directive, while endorsing and adopting the approach of “self-assessment”, also sought to establish a variety of basic duties, especially for the employer. Furthermore, the promotion of “social dialogue” in the field of health and safety at work was explicitly incorporated into detailed provisions in the 1989 Directive, introducing significant requirements for information, consultation and participation for workers and their representatives at the workplace. This 1989 Directive required compliance by 31 December 1992.

The Directive contains re-stated general principles concerning, in particular, the prevention of occupational risks, the protection of safety and health and the informing, consultation and training of workers and their representatives, as well as principles concerning the implementation of such measures. This measure constituted a first attempt to provide an overall complement to the technical harmonization directives designed to complete the internal market. The 1989 Directive also brought within its scope the provisions of the 1980 Framework Directive on risks arising from use at work of chemical, physical and biological agents. It parallels the ILO Convention concerning Occupational Safety and Health, 1981 (No. 155) and its accompanying Recommendation (No. 161).

The overall objectives of the 1989 Directive may be summarized as being:

- humanization of the working environment

- accident prevention and health protection at the workplace

- to encourage information, dialogue and balanced participation on safety and health by means of procedures and instruments

- to promote throughout the Community, the harmonious development of economic activities, a continuous and balanced expansion and an accelerated rise in the standard of living

- to encourage the increasing participation of management and labour in decisions and initiatives

- to establish the same level of health protection for workers in all undertakings, including small and medium-sized enterprises, and to fulfil the single market requirements of the Single European Act 1986; and

- the gradual replacement of national legislation by Community legislation.

General duties placed upon the employer include duties of awareness, duties to take direct action to ensure safety and health, duties of strategic planning to avoid risks to safety and health, duties to train and direct the workforce, duties to inform, consult and involve the workforce, and duties of recording and notification.

The Directive provided similar safeguards for small and medium-sized enterprises. It is stated, for example, that the size of the undertaking and/or establishment is a relevant matter in relation to determining the sufficiency of resources for dealing with the organization of protective and preventive measures. It is also a factor to be considered in relation to obligations concerning first aid, fire fighting and evacuation of workers. Furthermore, the Directive included a power for differential requirements to be imposed upon varying sizes of undertakings as regards documentation to be provided. Finally, in relation to the provision of information, it is stated that national measures “may take account, inter alia, of the size of the undertaking and/or establishment”.

Under the umbrella of the 1989 Directive, a number of individual directives have also been adopted. In particular, “daughter” directives have been adopted on minimum safety and health requirements for the workplace, for the use of work equipment, for the use of personal protective equipment, for the manual handling of loads, and for work with display screen equipment.

The following Directives have also been adopted:

- Council Directive of 20 December 1993 concerning the minimum safety and health requirements for work on board fishing vessels (93/103/EEC)

- Council Directive of 12 October 1993 amending Directive 90/679/EEC on the protection of workers from risks related to exposure to biological agents at work (93/88/EEC)

- Council Directive of 3 December 1992 on the minimum requirements for improving the safety and health protection of workers in surface and underground mineral-extracting industries (92/104/EEC)

- Council Directive of 3 November 1992 on the minimum requirements for improving the safety and health protection of workers in mineral-extracting industries that involve drilling (92/91/EEC)

- Council Directive of 19 October 1992 on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health at work of pregnant workers and workers who have recently given birth or who are breast-feeding (92/85/EEC)

- Council Directive of 24 June 1992 on the minimum requirements for the provision of safety and/or health signs at work (92/58/EEC)

- Council Directive of 24 June 1992 on the implementation of minimum safety and health requirements at temporary or mobile construction sites (92/57/EEC)

- Council Directive of 31 March 1992 on the minimum safety and health requirements for improved medical treatment on board vessels (92/29/EEC)

- Council Directive of 23 April 1990 on the contained use of genetically modified micro-organisms. (90/219/ EEC)

Since the passage of the Maastricht Treaty, further measures have been passed, namely: a Recommendation on a European schedule of industrial diseases; a directive on asbestos; a directive on safety and health signs at the workplace; a directive on medical assistance on board vessels; directives on health and safety protection in the extractive industries; and a directive introducing measures to promote improvements in the travel conditions of workers with motor disabilities.

The Single Market

The original Article 100 has been replaced by a new provision in the Treaty of European Union. The new Article 100 ensures that the European Parliament and the Economic and Social Committee must be consulted in all cases and not simply when the implementation of a directive would involve the amendment of legislation in one or more Member States.

The COSH Movement and Right to Know

Formed in the wake of the US Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, committees on occupational safety and health initially emerged as local coalitions of public health advocates, concerned professionals, and rank-and-file activists meeting to deal with problems resulting from toxics in the workplace. Early COSH groups started in Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and New York. In the south, they evolved in conjunction with grass roots organizations such as Carolina Brown Lung, representing textile mill workers suffering from byssinosis. Currently there are 25 COSH groups around the country, at various stages of development and funded through a wide variety of methods. Many COSH groups have made a strategic decision to work with and through organized labor, recognizing that union-empowered workers are the best equipped to fight for safe working conditions.

COSH groups bring together a broad coalition of organizations and individuals from unions, the public health community and environmental interests, including rank-and-file safety and health activists, academics, lawyers, doctors, public health professionals, social workers and so on. They provide a forum in which interest groups that do not normally work together can communicate about workplace safety and health problems. In the COSH, workers have a chance to discuss the safety and health issues they confront on the shop floor with academics and medical experts. Through such discussions, academic and medical research can get translated for use by working people.

COSH groups have been highly active politically, both through traditional means (such as lobbying campaigns) and through more colorful methods (such as picketing and carrying coffins past the homes of anti-labor elected officials). COSH groups played a key role in the struggles for local and state right-to-know legislation, building broad-based coalitions of union, environmental and public interest organizations to support this cause. For example, the Philadelphia area COSH group (PHILAPOSH) ran a campaign which resulted in the first city right-to-know law passed in the country. The campaign climaxed when PHILAPOSH members dramatized the need for hazard information by opening an unmarked pressurized canister at a public hearing, sending members of the City Council literally diving under tables as the gas (oxygen) escaped.

Local right-to-know campaigns eventually yielded more than 23 local and state right-to-know laws. The diversity of requirements was so great that chemical corporations ultimately demanded a national standard, so they would not have to comply with so many differing local regulations. What happened with COSH groups and right to know is an excellent example of how the efforts of labor and community coalitions working at the local level can combine to have a powerful national impact on occupational safety and health policy.

Right to Know: The Role of Community-Based Organizations

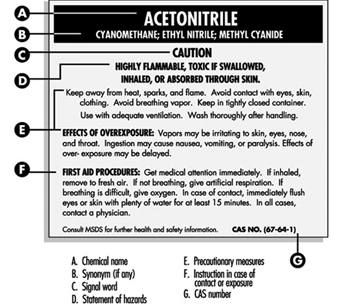

In the context of occupational health and safety, “right to know” refers generally to laws, rules and regulations requiring that workers be informed about health hazards related to their employment. Under right-to-know mandates, workers who handle a potentially harmful chemical substance in the course of their job duties cannot be left unaware of the risk. Their employer is legally obligated to tell them exactly what the substance is chemically, and what kind of health damage it can cause. In some cases, the warning must also include advice on how to avoid exposure and must state the recommended treatment in case exposure does occur. This policy contrasts sharply with the situation it was meant to replace, unfortunately still prevailing in many workplaces, in which workers knew the chemicals they used only by trade names or generic names such as “Cleaner Number Nine” and had no way to judge whether their health was being endangered.

Under right-to-know mandates, hazard information is usually conveyed through warning labels on workplace containers and equipment, supplemented by worker health and safety training. In the United States, the major vehicle for worker right to know is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Hazard Communication Standard, finalized in 1986. This federal regulatory standard requires labelling of hazardous chemicals in all private-sector workplaces. Employers must also provide workers access to a detailed Materials Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) on each labelled chemical, and provide worker training in safe chemical handling. Figure 1 shows a typical US right-to-know warning label.

Figure 1. Right-to-know chemical warning label

It should be noted that as a policy direction, the provision of hazard information differs greatly from direct regulatory control of the hazard itself. The labelling strategy reflects a philosophical commitment to individual responsibility, informed choice and free market forces. Once armed with knowledge, workers are in theory supposed to act in their own best interests, demanding safe working conditions or finding different work if necessary. Direct regulatory control of occupational hazards, by contrast, assumes a need for more active state interventions to counter the power imbalances in society that prevent some workers from making meaningful use of hazard information on their own. Because labelling implies that the informed workers bear ultimate responsibility for their own occupational safety, right-to-know policies occupy a somewhat ambiguous status politically. On the one hand, they are cheered by labour advocates as a victory enabling workers to protect themselves more effectively. On the other hand, they can threaten workers’ interests if right to know is allowed to replace or weaken other occupational safety and health regulations. As activists are quick to point out, the “right to know” is a starting point that needs to be complemented with the “right to understand” and the “right to act”, as well as with continued effort to control work hazards directly.

Local organizations play a number of important roles in shaping the real-world significance of worker right-to-know laws and regulations. First and foremost, these rights often owe their very existence to public interest groups, many of them community based. For example, “COSH groups” (grass-roots Committees on Occupational Safety and Health) were central participants in the lengthy rule-making and litigation that went into establishing the Hazard Communication Standard in the United States. See box for a more detailed description of COSH groups and their activities.

Organizations in the local community also play a second critical role: assisting workers to make more effective use of their legal rights to hazard information. For example, COSH groups advise and assist workers who feel they may suffer retaliation for seeking hazard information; raise consciousness about reading and observing warning labels; and help bring to light employer violations of right-to-know requirements. This help is particularly important to workers who feel intimidated in using their rights due to low education levels, low job security, or lack of a supportive trade union. COSH groups also assist workers in interpreting the information contained on labels and in Material Safety Data Sheets. This kind of support is badly needed for workers with limited literacy. It can also help workers with good reading skills but insufficient technical background to understand the MSDSs, which are often written in scientific language confusing to an untrained reader.

Worker right to know is not only a matter of transmitting factual information; it also has an emotional side. Through right to know, workers may learn for the first time that their jobs are dangerous in ways they had not realized. This disclosure can stir up feelings of betrayal, outrage, dread and helplessness—sometimes with great intensity. Accordingly, a third important role that some community-based organizations play in worker right to know is to provide emotional support for workers struggling to deal with the personal implications of hazard information. Through self-help support groups, workers receive validation, a chance to express their feelings, a sense of collective support, and practical advice. In addition to COSH groups, examples of this kind of self-help organization in the United States include Injured Workers, a national network of support groups that provides a newsletter and locally available support meetings for individuals contemplating or involved in workers’ compensation claims; the National Center for Environmental Health Strategies, an advocacy organization located in New Jersey, serving those at risk of or suffering from multiple chemical sensitivity; and Asbestos Victims of America, a national network centred in San Francisco that offers information, counselling, and advocacy for workers exposed to asbestos.

A special case of right to know involves locating workers known to have been exposed to occupational hazards in the past, and informing them of their elevated health risk. In the United States, this kind of intervention is called “high-risk worker notification”. Numerous state and federal agencies in the United States have developed programmes of worker notification, as have some unions and a number of large corporations. The federal government agency most actively involved with worker notification at present is the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). This agency carried out several ambitious community-based pilot programmes of worker notification in the early 1980s, and now includes worker notification as a routine part of its epidemiological research studies.

NIOSH’s experience with this kind of information provision is instructive. In its pilot programmes, NIOSH undertook to develop accurate lists of workers with probable exposure to hazardous chemicals in a particular plant; to send personal letters to all workers on the list, informing them of the possibility of health risk; and, where indicated and feasible, to provide or encourage medical screening. It immediately became obvious, however, that the notification did not remain a private matter between the agency and each individual worker. On the contrary, at every step the agency found its work affected by community-based organizations and local institutions.

NIOSH’s most controversial notification took place in the early 1980s in Augusta, Georgia, with 1,385 chemical workers who had been exposed to a potent carcinogen (β-naphthylamine). The workers involved, predominantly African-American males, were unrepresented by a union and lacked resources and formal education. The community’s social climate was, in the words of programme staff, “highly polarized by racial discrimination, poverty, and substantial lack of understanding of toxic hazards”. NIOSH helped establish a local advisory group to encourage community involvement, which quickly took on a life of its own as more militant grass-roots organizations and individual worker advocates joined the effort. Some of the workers sued the company, adding to the controversies already surrounding the programme. Local organizations such as the Chamber of Commerce and the county Medical Society also became involved. Even many years later, echoes can still be heard of the conflicts among local organizations involved in the notification. In the end, the programme did succeed in informing the exposed workers of their life-long risk for bladder cancer, a highly treatable disease if caught early. Over 500 of them were medically screened through the programme, and a number of possibly life-saving medical interventions resulted.

A striking feature of the Augusta notification is the central role played by the news media. Local news coverage of the programme was extremely heavy, including over 50 newspaper articles and a documentary film about the chemical exposures (“Lethal Labour”) shown on local TV. This publicity reached a wide audience and had enormous impact on the notified workers and the community as a whole, leading the NIOSH project director to observe that “in actuality, the news media perform the real notification”. In some situations, it may be useful to regard local journalists as an intrinsic part of right to know and plan a formal role for them in the notification process to encourage more accurate and constructive reporting.

While the examples here are drawn from the United States, the same issues arise worldwide. Worker access to hazard information represents a step forward in basic human rights, and has properly become a focal point of political and service effort for pro-worker community-based organizations in many countries. In nations with weak legal protections for workers and/or weak labour movements, community-based organizations are all the more important in terms of the three roles discussed here—advocating for stronger right-to-know (and right-to-act) laws; assisting workers to use right-to-know information effectively; and providing social and emotional support for those who learn they are at risk from work hazards.

Community-Based Organizations

The role of community groups and the voluntary sector in occupational health and safety has grown rapidly during the past twenty years. Hundreds of groups spread across at least 30 nations act as advocates for workers and sufferers from occupational diseases, concentrating on those whose needs are not met within workplace, trade union or state structures. Health and safety at work forms part of the brief of many more organizations which fight for workers’ rights, or on broader health or gender-based issues.

Sometimes the life-span of these organizations is short because, in part as a result of their work, the needs to which they respond become recognized by more formal organizations. However, many community and voluntary sector organizations have now been in existence for 10 or 20 years, altering their priorities and methods in response to changes in the world of work and the needs of their constituency.

Such organizations are not new. An early example was the Health Care Association of the Berlin Workers Union, an organization of doctors and workers which provided medical care for 10,000 Berlin workers in the mid-nineteenth century. Before the rise of industrial trade unions in the nineteenth century, many informal organizations fought for a shorter working week and the rights of young workers. The lack of compensation for certain occupational diseases formed the basis for organizations of workers and their relatives in the United States in the mid-1960s.

However, the recent growth of community and voluntary sector groups can be traced to the political changes of the late 1960s and 1970s. Increasing conflict between workers and employers focused on working conditions as well as pay.

New legislation on health and safety in the industrialized countries arose from an increased concern with health and safety at work amongst workers and trade unions, and these laws in turn led to further increases in public awareness. While the opportunities offered by this legislation have seen health and safety become an area for direct negotiation between employers, trade unions and government in most countries, workers and others suffering from occupational disease and injury have frequently chosen to exert pressure from outside these tripartite discussions, believing that there should be no negotiation over fundamental human rights to health and safety at work.

Many of the voluntary sector groups formed since that time have also taken advantage of cultural changes in the role of science in society: an increasing awareness amongst scientists of the need for science to meet the needs of workers and communities, and an increase in the scientific skills of workers. Several organizations recognize this alliance of interest in their title: the Academics and Workers Action (AAA) in Denmark, or the Society for Participatory Research in Asia, based in India.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The voluntary sector identifies as its strengths an immediacy of response to emerging problems in occupational health and safety, open organizational structures, the inclusion of marginalized workers and sufferers from occupational disease and injury, and a freedom from institutional constraints on action and utterance. The problems of the voluntary sector are uncertain income, difficulties in marrying the styles of voluntary and paid staff, and difficulties in coping with the overwhelming unmet needs of workers and sufferers from occupational ill-health.

The transient character of many of these organizations has already been mentioned. Of 16 such organizations known in the UK in 1985, only seven were still in existence in 1995. In the meantime, 25 more had come into existence. This is characteristic of voluntary organizations of all kinds. Internally they are frequently non-hierarchically organized, with delegates or affiliates from trade unions and other organizations as well as others suffering from work-related health problems. While links with trade unions, political parties and governmental bodies are essential to their effectiveness in improving conditions at work, most have chosen to keep such relationships indirect, and to be funded from several sources—typically, a mixture of statutory, labour movement, commercial or charitable sources. Many more organizations are entirely voluntary or produce a publication from subscriptions which cover printing and distribution costs only.

Activities

The activities of these voluntary sector bodies can be broadly categorized as based on single hazards (illnesses, multinational companies, employment sectors, ethnic groups or gender); advice centres; occupational health services; newsletter and magazine production; research and educational bodies; and supranational networks.

Some of the longest-established bodies fight for the interests of sufferers from occupational diseases, as shown in the following list, which summarizes the principal concerns of community groups around the world: multiple chemical sensitivity, white lung, black lung, brown lung, Karoshi (sudden death through overwork), repetitive strain injury, accident victims, electrical sensitivity, women’s occupational health, Black and ethnic minority occupational health, white lung (asbestos), pesticides, artificial mineral fibres, microwaves, visual display units, art hazards, construction work, Bayer, Union Carbide, Rio Tinto Zinc.

Concentration of efforts in this way can be particularly effective; the publications of the Center for Art Hazards in New York City were models of their kind, and projects drawing attention to the special needs of migrant minority ethnic workers have had successes in the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan and elsewhere.

A dozen organizations around the world fight for the particular health problems of ethnic minority workers: Latino workers in the United States; Pakistani, Bengali and Yemeni workers in England; Moroccan and Algerian workers in France; and South-East Asian workers in Japan among others. Because of the severity of the injuries and illnesses suffered by these workers, adequate compensation, which often means recognition of their legal status, is a first demand. But an end to the practice of double standards in which ethnic minority workers are employed in conditions which majority groups will not tolerate is the main issue. A great deal has been achieved by these groups, in part through securing better provision of information in minority languages on health and safety and employment rights.

The work of the Pesticides Action Network and its sister organizations, especially the campaign to get certain pesticides banned (the Dirty Dozen Campaign) has been notably successful. Each of these problems and the systematic abuse of the working and external environments by certain multinational companies are intractable problems, and the organizations dedicated to resolving them have in many cases won partial victories but have set themselves new goals.

Advice Centres

The complexity of the world of work, the weakness of trade unions in some countries, and the inadequacy of statutory provision of health and safety advice at work, have resulted in the setting up of advice centres in many countries. The most highly developed networks in English-speaking countries deal with tens of thousands of enquiries each year. They are largely reactive, responding to needs as reflected by those who contact them. Recognized changes in the structure of advanced economies, towards a reduction in the size of workplaces, casualization, and an increase in informal and part-time work (each of which creates problems for the regulation of working conditions) have enabled advice centres to obtain funding from state or local government sources. The European Work Hazards Network, a network of workers and workers’ health and safety advisers, has recently received European Union funding. The South African advice centres network received EU development funding, and community-based COSH groups in the United States at one time received funds through the New Directions programme of the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Occupational Health Services

Some of the clearest successes of the voluntary sector have been in improving the standard of occupational health service provision. Organizations of medically and technically trained staff and workers have demonstrated the need for such provision and pioneered novel methods of delivering occupational health care. The sectoral occupational health services which have been brought into existence progressively over the last 15 years in Denmark received powerful advocacy from the AAA particularly for the role of workers’ representatives in management of the services. The development of primary-care-based services in the UK and of specific services for sufferers from work-related upper limb disorders in response to the experience of workers’ health centres in Australia are further examples.

Research

Changes within science during the 1960s and 1970s have lead to experimentation with new methods of investigation described as action research, participatory research or lay epidemiology. The definition of research needs by workers and their trade unions has created an opportunity for a number of centres specializing in carrying out research for them; the network of Science Shops in the Netherlands, DIESAT, the Brazilian trade union health and safety resource centre, SPRIA (the Society for Participatory Research in Asia) in India, and the network of centres in the Republic of South Africa are amongst the longest established. Research carried out by these bodies acts as a route by which workers’ perceptions of hazards and their health become recognized by mainstream occupational medicine.

Publications

Many voluntary sector groups produce periodicals, the largest of which sell thousands of copies, appear up to 20 times a year and are read widely within statutory, regulatory and trade union bodies as well as by their target audience amongst workers. These are effective networking tools within countries (Hazards bulletin in the United Kingdom; Arbeit und Ökologie (Work and the Environment) in Germany). The priorities for action promoted by these periodicals may initially reflect cultural differences from other organizations, but frequently become the priorities of trades unions and political parties; the advocacy of stiffer penalties for breaking health and safety law and for causing injury to, or the death of, workers are recurrent themes.

International Networks

The rapid globalization of the economy has been reflected in trade unions through the increasing importance of the international trade secretariats, area-based trade union affiliations like the Organization of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU), and meetings of workers employed in particular sectors. These new bodies frequently take up health and safety concerns, the African Charter on Occupational Health and Safety produced by OATUU being a good example. In the voluntary sector international links have been formalized by groups which concentrate on the activities of particular multinational companies (contrasting the safety practices and health and safety record of constituent businesses in different parts of the world, or the health and safety record in particular industries, such as cocoa production or tyre manufacture), and by networks across the major free trade areas: NAFTA, EU, MERCOSUR and East Asia. All these international networks call for the harmonization of standards of worker protection, the recognition of, and compensation for, occupational disease and injury, and worker participation in health and safety structures at work. Upward harmonization, to the best extant standard, is a consistent demand.

Many of these international networks have grown up in a different political culture from the organizations of the 1970s, and see direct links between the working environment and the environment outside the workplace. They call for higher standards of environmental protection and make alliances between workers in companies and those who are affected by the companies’ activities; consumers, indigenous people in the vicinity of mining operations, and other residents. The international outcry following the Bhopal disaster has been channelled through the Permanent People’s Tribunal on Industrial Hazards and Human Rights, which has made a series of demands for the regulation of the activities of international business.

The effectiveness of voluntary sector organizations can be assessed in different ways: in terms of their services to individuals and groups of workers, or in terms of their effectiveness in bringing about changes in working practice and the law. Policy making is an inclusive process, and policy proposals rarely originate from one individual or organization. However, the voluntary sector has been able to reiterate demands which were at first unthinkable until they have become acceptable.

Some recurrent demands of voluntary and community groups include:

- a code of ethics for multinational companies

- higher penalties for corporate manslaughter

- workers’ participation in occupational health services

- recognition of additional industrial diseases (e.g., for the purpose of compensation awards)

- bans on the use of pesticides, asbestos, artificial mineral fibres, epoxy resins and solvents.

The voluntary sector in occupational health and safety exists because of the high cost of providing a healthy working environment and appropriate services and compensation for the victims of poor working conditions. Even the most extensive systems of provision, like those in Scandinavia, leave gaps which the voluntary sector attempts to fill. The increasing pressure for deregulation of health and safety in the long-industrialized countries in response to competitive pressures from transitional economies has created a new campaign theme: the maintenance of high standards and upward harmonization of standards in different nations’ legislation.

While they can be seen as performing an essential role in the process of initiating legislation and regulation, they are necessarily impatient about the speed with which their demands are accepted. They will continue to grow in importance wherever workers find that state provisions fall short of what is needed.

Occupational Health as a Human Right

* This article is based on a presentation to the Columbia University Seminars on Labour and Employment, sponsored by the Center for the Study of Human Rights, Columbia University, February 13, 1995.

“The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being .... The achievement of any State in the promotion and protection of health is of value to all.” Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO).

The concept of universality is a fundamental tenet of international law. This concept is exemplified by the issues raised in occupational safety and health because no work is immune from the dangers of occupational hazards. (Examples of the literature describing occupational safety and health hazards from different types of work include: Corn 1992; Corn 1985; Faden 1985; Feitshans 1993; Nightingale 1990; Rothstein 1984; Stellman and Daum 1973; Weeks, Levy and Wagner 1991.)

The universal threat to the fundamental human rights of life and security of person posed by unhealthy working conditions has been characterized in international human rights instruments and ILO standards. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, proclaimed in 1948 (United Nations General Assembly 1994) Article 3, “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person”. The Preamble to the ILO Constitution considers “the protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment” as a precondition to “Universal and lasting peace”. Therefore, improvement of the conditions of living and work is a fundamental component of the ILO’s view of universal rights.

As described in a recent exhibit at the UN Secretariat in New York, United Nations staff have been tortured, imprisoned, kidnapped and even killed by terrorists. United Nations Commission on Human Rights, (UNCHR) Resolution 1990/31 pays attention to these hazards, underscoring the need to implement existing mechanisms for compliance with international human rights to occupational safety and health. For these professionals, their role as a conduit for life-saving communication about other people, and their commitment to their employer’s principled work, placed them at equal if not greater risk to other workers, without the benefit of recognizing occupational safety and health concerns when formulating their own work agenda.

All workers share the right to safe and healthful working conditions, as articulated in international human rights instruments, regardless of whether they be confronted in fieldwork, in traditional offices or workplace settings, or as “telecommuters”. This view is reflected in international human rights instruments regarding occupational safety and health, codified in the United Nations Charter in 1945 (United Nations 1994) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, amplified in major international covenants on human rights (e.g., the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966), described in major human rights treaties, such as the International Convention on the Elimination of All Discrimination Against Women passed in 1979, and embodied in the work of the ILO and the WHO as well as in regional agreements (see below).

Defining occupational health for the purposes of understanding the magnitude of the governmental and employers’ responsibility under international law is complex; the best statement is found in the Preamble of the Constitution of the WHO: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” The term “well-being” is extremely important, because it is consistently used in human rights instruments and international agreements pertaining to health. Equally important is the construction of the definition itself: by its very terms, this definition reveals the consensus that health is a composite of the interaction of several complex factors: physical, mental and social well-being, all of these together being measured by an adequate standard of well-being that is greater than “merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This term, by its very nature, is not tied to specific standards of health, but is amenable to interpretation and application in a flexible framework for compliance.

Thus, the legal foundation for implementing international human rights to occupational health protections in the workplace from the perspective of security of the person as a facet of protecting the human right to health constitutes an important corpus of international labour standards. The question therefore remains whether the right of individuals to occupational safety and health falls under the rubric of international human rights, and if so, which mechanisms can be deployed to assure adequate occupational safety and health. Further, developing new methods for resolving compliance issues will be the major task for ensuring the application of human rights protection in the next century.

Overview of International Rights to Protectionfor Occupational Safety and Health

Law of human rights reflected in the United NationsCharter

Protection of the right to health is among the fundamental constitutional principles of many nations. In addition, an international consensus exists regarding the importance of providing safe and healthful employment, which is reflected in many international human rights instruments, echoing legal concepts from many nations, including national or local legislation or constitutionally guaranteed health protections. Laws requiring inspections to prevent occupational accidents were passed in Belgium in 1810, France in 1841 and Germany in 1839 (followed by medical examination requirements in 1845).The issue of “entitlements” to health care and health protections was raised in the analysis of the potential for US ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (e.g., Grad and Feitshans 1992). Broader questions regarding the human right to health protections have been addressed, although not fully resolved, in the United Nations Charter; in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; in Articles 7 and 12 of the International Covenant on Economic and Social Rights; and in subsequent standards by the ILO and the WHO, and other UN-based international organizations.

Under the United Nations Charter the contracting parties state their aspiration to “promote” economic and social advancement and “better standards of life”, including the promotion of human rights protections, in Article 13. Using language that recalls the ILO’s Constitutional mandate under the Treaty of Versailles, Article 55 specifically notes the linkage between the “creation of conditions of stability and well-being” for peace and “higher standards of living” and “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms”. The debate regarding the interpretation of these terms, and whether they encompassed all or only a fraction of recognized constitutional rights of UN Member States, was unduly politicized throughout the Cold War Era.

This handful of basic documents share one weakness, however—they offer vague descriptions of protections for life, security of the person and economically-based rights to employment without explicitly mentioning occupational safety and health. Each of these documents employs human rights rhetoric ensuring “adequate” health and related basic human rights to health, but it is difficult to patch together a consensus regarding the quality of care or “better standards of life” for implementing protections.

Occupational safety and health protections underthe Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Security of the person, as discussed in UDHR Article 3

Although there is no case-law interpreting this term, Article 3 of the UDHR ensures each person’s right to life. This includes occupational health hazards and the effects of occupational accidents and work-related diseases.

The cluster of employment rights in UDHR Articles 23, 24 and 25

There is a small but significant cluster of rights relating to employment and “favourable conditions of work” listed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The principles articulated in three consecutive articles of the UDHR are an outgrowth of history, reflected in older laws. One problem exists from the standpoint of occupational health analysis: the UDHR is a very important, widely-accepted document but it does not specifically address the issues of occupational safety and health. Rather, references to issues surrounding security of person, quality of conditions of work and quality of life allow for an inference that occupational safety and health protections fall under UDHR’s rubric. For example, while the right to work in “favourable conditions of work” is not actually defined, occupational health and safety hazards certainly impact upon the achievement of such social values. Also, the UDHR requires that human rights protections at the worksite ensure the preservation of “human dignity”, which has implications not only for the quality of life, but for the implementation of programmes and strategies that prevent degrading working conditions. The UDHR therefore provides a vague but valuable blueprint for international human rights activity surrounding issues of occupational safety and health.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

The meaning and enforcement of these rights are amplified by the principles enumerated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), Part III, Article 6 and 7b, which assures all workers the right to “Safe and healthy working conditions”. Article 7 provides greater insight to the meaning of the right to just and favourable conditions of work. “Favourable conditions of work” includes wages and hours of work (ICESCR Article 7.1 (a) (i)) as well as “Safe and healthy working conditions” (Summers 1992). The use of this phrase within the context of favourable conditions of work therefore lends greater meaning to the UDHR’s protections and demonstrates the clear nexus between other human rights principles and protection of occupational safety and health, as further amplified in ICESCR Article 12.

Promotion of industrial hygiene under Article 12of the International Covenant on Economic, Socialand Cultural Rights

Of all the UN-based international human rights documents, ICESCR Article 12 most clearly and deliberately addresses health, referring to the explicit right to health protection through “industrial hygiene” and protection against “occupational disease”. Further, Article 12’s discussion regarding improved industrial hygiene is consistent with Article 7(b) of the ICESCR regarding safe and healthful working conditions. Yet, even this express guarantee of occupational safety and health protection does not offer detailed exposition of the meaning of these rights, nor does it list the possible approaches that could be applied for achieving the ICESCR’s goals. Consistent with the principles articulated in many other international human rights documents, Article 12 employs deliberate language that recalls the WHO’s Constitutional notions of health. Without question, Article 12 embraces the notion that health concerns and attention to individual well-being include occupational safety and health. Article 12 reads:

The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.... The steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include those necessary for: ...

(b)The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene;

(c)The prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases.

Significantly, Article 12 also pays direct attention to the impact of occupational disease on health, thereby accepting and giving validity to a sometimes-controversial area of occupational medicine as worthy of human rights protection. Under Article 12 the States Parties recognize the right to physical and mental health proclaimed indirectly in Article 25 of the UDHR, in the American Declaration, the European Social Charter, and the revised Organization of American States (OAS) Charter (see below). Additionally, in Paragraph 2, they commit themselves to a minimum of four “steps” to be taken to achieve the “full realization” of this right.

It should be noted that Article 12 does not define “health”, but follows the definition stated in the WHO Constitution. According to Grad and Feitshans (1992), Paragraph 1 of the Draft Covenant prepared under the auspices of the Commission on Human Rights, however, did define the term by applying the definition in the WHO Constitution: “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Like the ILO with respect to Articles 6-11 of the ICESCR, WHO provided technical help in drafting Article 12. The Third Committee did not accept WHO’s efforts to include a definition, arguing that such detail would be out of place in a legal text, that no other definitions were included in other articles of the Covenant, and that the proposed definition was incomplete.

The words “environmental and industrial hygiene” appear without the benefit of interpretive information in the text of the preparatory records. Citing other resolutions of the 1979 World Health Assembly, the report also expresses concern for “the uncontrolled introduction of some industrial and agricultural process(es) with physical, chemical, biological and psychosocial hazards” and notes that the Assembly further urged Member States “to develop and strengthen occupational health institutions and to provide measures for preventing hazards in work places” (Grad and Feitshans 1992). Repeating a theme expressed in many prior international human rights documents, “The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” is a goal clearly shared by employers, workers and governments of many nations—a goal that unfortunately remains as elusive as it is universal.

International Convention on the Eliminationof All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979), Part III, Article 11(a), states that “The right to work is an inalienable right of all human beings”, and Article 11(f) lays down “The right of protection of health and to safety in working conditions, including the safeguarding of the function of reproduction”.

Article 11.2(a) prohibits “sanctions, dismissal on the grounds of maternity leave”, a subject of profound contemporary and historical conflict and violation of international human rights, under many legal systems of UN Member States. For pregnant women and other people who work, these important issues remain unresolved in the jurisprudence of pregnancy. Thus, Article 11.2 is unquestionably geared to overturning generations of ingrained institutional discrimination under law, which was an outgrowth of mistaken values regarding women’s ability during pregnancy or while raising a family. Issues from the perspective of the jurisprudence of pregnancy include the dichotomy between protectionism and paternalism which has been played out in litigation throughout the twentieth century. (US Supreme Court cases in this area range from a concern for limiting the hours of women’s work because of their need to be home raising families, upheld in Muller v. the State of Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908), to the decision banning forced sterilizations of women who are exposed to reproductive health hazards in the workplace among other things in UAW v. Johnson Controls, 499 U.S. 187 (1991) (Feitshans 1994). The imprint of this dichotomy on the conceptual matrix of this Convention is reflected in Article 11.2(d), but is not clearly resolved since “special protections”, which are often necessary to prevent the disproportionately dangerous effects of working conditions, are often inappropriately viewed as beneficial.

Under the terms of this Convention, Article 11.2(d) endeavours “To provide special protection to women during pregnancy in types of work proved to be harmful to them”. Many facets of this provision are unclear, such as: what is meant by special protection; are effects limited to maternal harm during pregnancy; and if not, what are the implications for foetal protection? It is unclear from this Convention, however, what the standard of proof is to make a “special protection” necessary or acceptable, and also what is the scope of an acceptable protective mechanism.