Thallium

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Thallium (Tl) is fairly widely distributed in the earth’s crust in very low concentrations; it is also found as an accompanying substance of other heavy metals in pyrites and blendes, and in the manganese nodules on the ocean floor.

Thallium is used in the manufacture of thallium salts, mercury alloys, low-melting glasses, photoelectric cells, lamps and electronics. It is used in an alloy with mercury in low-range glass thermometers and in some switches. It has also been used in semiconductor research and in myocardial imaging. Thallium is a catalyst in organic synthesis.

Thallium compounds are used in infrared spectrometers, crystals and other optical systems. They are useful for colouring glass. While many thallium salts have been prepared, few are of commercial significance.

Thallium hydroxide (TlOH), or thallous hydroxide, is produced by dissolving thallium oxide in water, or by treating thallium sulphate with barium hydroxide solution. It can be used in the preparation of thallium oxide, thallium sulphate or thallium carbonate.

Thallium sulphate (Tl2SO4), or thallous sulphate, is produced by dissolving thallium in hot concentrated sulphuric acid or by neutralizing thallium hydroxide with dilute sulphuric acid, followed by crystallization. Because of its outstanding efficacy in the destruction of vermin, particularly rats and mice, thallium sulphate is one of the most important of the thallium salts. However, some western European countries and the United States have prohibited the use of thallium on the grounds that it is inadvisable that such a toxic substance should be easily obtainable. In other countries, following the development of warfarin resistance in rats, the use of thallium sulphate has increased. Thallium sulphate is also used in semiconductor research, optical systems and in photoelectric cells.

Hazards

Thallium is a skin sensitizer and cumulative poison which is toxic by ingestion, inhalation or skin absorption. Occupational exposure may occur during the extraction of the metal from thallium-bearing ores. Inhalation of thallium has resulted from the handling of flue dusts and the dusts from roasting of pyrites. Exposure may also occur during the manufacture and use of thallium-salt vermin exterminators, the manufacture of thallium-containing lenses and separation of industrial diamonds. The toxic action of thallium and its salts is well documented from reports of cases of acute non-occupational poisoning (not infrequently fatal) and from instances of suicidal and homicidal use.

Occupational thallium poisoning is normally the result of moderate, long-term exposure, and the symptoms are usually far less marked than those observed in acute accidental, suicidal or homicidal intoxication. The course is usually unremarkable and characterized by subjective symptoms such as asthenia, irritability, pains in the legs, some nervous system disorders. Objective symptoms of polyneuritis may not be demonstrable for quite some time. The early neurologic findings include changes in the superficially provoked tendon reflexes and a pronounced weakness and fall-off in the speed of pupil reflexes.

The victim’s occupational history will usually give the first clue to the diagnosis of thallium poisoning since a considerable time may elapse before the rather vague initial symptoms are replaced by the polyneuritis followed by loss of hair. Where massive hair loss occurs, the likelihood of thallium poisoning is readily suspected. However, in occupational poisoning, where exposure is usually moderate but protracted, the loss of hair may be a late symptom and often noticeable only after the appearance of polyneuritis; in cases of slight poisoning, it may not occur at all.

The two principal criteria for the diagnosis of occupational thallium poisoning are:

- occupational history which shows that the patient has or may have been exposed to thallium in such work as rodenticide handling, thallium, lead, zinc or cadmium production, or the production or use of various thallium salts

- neurological symptoms, dominated initially by subjective changes in the form of paraesthesia (both hyperaesthesia and hypoaesthesia) and, subsequently, by reflex changes.

Concentrations of Tl in urine above 500 µg/l have been associated with clinical poisoning. At concentrations of 5 to 500 µg/l the magnitude of risk and severity of adverse effects on humans are uncertain.

Long-term experiments with radioactive thallium have shown marked excretion of thallium in both urine and faeces. On autopsy, the highest thallium concentrations are found in the kidneys, but moderate concentrations may also be present in the liver, other internal organs, muscles and bones. It is striking that, although the principal signs and symptoms of thallium poisoning originate from the central nervous system, only very low concentrations of thallium are retained there. This may be due to extreme sensitivity to even very small amounts of the thallium acting on the enzymes, the transmission substances, or directly on the brain cells.

Safety and Health Measures

The most effective measure against the dangers associated with the manufacture and use of this group of extremely toxic substances is the substitution of a less harmful material. This measure should be adopted wherever possible. When thallium or its compounds must be used, the strictest safety precautions should be taken to ensure that the concentration in the workplace air is kept below permissible limits and that skin contact is prevented. Continuous inhalation of such concentrations of thallium during normal working days of 8 hours may cause the urine level to exceed the above permissible levels.

Persons involved in work with thallium and its compounds should wear personal protective equipment, and respiratory protective equipment is essential where there is the possibility of dangerous inhalation of airborne dust. A complete set of working clothes is essential; these clothes should be washed regularly and kept in accommodation separate from that employed for ordinary clothes. Washing and shower facilities should be provided and scrupulous personal hygiene encouraged. Workrooms must be kept scrupulously clean, and eating, drinking or smoking at the workplace prohibited.

Tellurium

Gunnar Nordberg

Tellurium (Te) is a heavy element with the physical properties and silvery lustre of a metal, yet with the chemical properties of a non-metal such as sulphur or arsenic. Tellurium is known to exist in two allotropic forms—the hexagonal crystalline form (isomorphous with grey selenium) and an amorphous powder. Chemically, it resembles selenium and sulphur. It tarnishes slightly in air, but in the molten state it burns to give the white fumes of tellurium dioxide, which is only sparingly soluble in water.

Occurrence and Uses

The geochemistry of tellurium is imperfectly known; it is probably 50 to 80 times more rare than selenium in the lithosphere. It is, like selenium, a by-product of the copper-refining industry. The anodic slimes contain up to 4% tellurium.

Tellurium is used to improve the machinability of “free-cutting” copper and certain steels. The element is a powerful carbide stabilizer in cast irons, and it is used to increase the depth of chill in castings. Additions of tellurium improve the creep strength of tin. The chief use of tellurium is, however, in the vulcanizing of rubber, since it reduces the time of curing and endows the rubber with increased resistance to heat and abrasion. In much smaller quantities, tellurium is used in pottery glazes and as an additive to selenium in metal rectifiers. Tellurium acts as a catalyst in some chemical processes. It is found in explosives, antioxidants and in infrared-transmitting glasses. Tellurium vapour is used in “daylight lamps”, and tellurium-radioiodinated fatty acid (TPDA) has been used for myocardial scanning.

Hazards

Cases of acute industrial poisoning have occurred as a result of metallic tellurium fumes being absorbed into the lungs.

A study of foundry workers throwing tellurium pellets by hand into molten iron with the emanation of dense white fumes showed that persons exposed to tellurium concentrations of 0.01 to 0.74 mg/m3 had higher urinary tellurium levels (0.01 to 0.06 mg/l) than workers exposed to concentrations of 0.00 to 0.05 mg/m3 (urinary concentrations of 0.00 to 0.03 mg/l). The most common sign of exposure was a garlic odour of the breath (84% of cases) and a metallic taste in the mouth (30% of cases). Workers complained of somnolence in the afternoons and loss of appetite, but suppression of sweat did not occur; blood and central nervous system test results were normal. One worker still had a garlic odour in his breath and tellurium in the urine after being away from the work for 51 days.

In laboratory workers who were exposed to fumes of melting tellurium-copper (fifty/fifty) alloy for 10 min, there were no immediate symptoms, but the effects of stinking breath were pronounced. Since tellurium forms a sparingly soluble oxide with no acidic reaction, there is no danger to the skin or to the lungs from tellurium dust or fumes. The element is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and lungs, and excreted in the breath, faeces and urine.

Tellurium dioxide (TeO2), hydrogen telluride (H2Te) and potassium tellurite (K2TeO3) are of industrial health significance. Because tellurium forms its oxide over 450 ºC and the dioxide formed is almost insoluble in water and body fluids, tellurium appears to be less of an industrial hazard than is selenium.

Hydrogen telluride is a gas which decomposes slowly to its elements. It has a similar smell and toxicity to hydrogen selenide, and is 4.5 times heavier than air. There have been reports that hydrogen telluride causes irritation to the respiratory tract.

One unique case is reported in a chemist who was admitted to hospital after accidently inhaling tellurium hexafluoride gas whilst engaged on making the tellurium esters. Streaks of blue-black pigmentation below the skin surface were seen on the webs of his fingers and to a lesser degree on his face and neck. The photographs show very clearly this rare example of true skin absorption by a tellurium ester, which was reduced to black elemental tellurium during its passage through the skin.

Animals exposed to tellurium have developed central nervous system and red blood cell effects.

Safety and Health Measures

Where tellurium is being added to molten iron, lead or copper, or being vaporized onto a surface under vacuum, an exhaust system should be installed with a minimum air speed of 30 m/min to control vapour emission. Tellurium should preferably be used in pellet form for alloying purposes. Routine atmospheric determinations should be made to ensure that the concentration is maintained below the recommended levels. Where no specific permissible concentration is given for hydrogen telluride; however, it is considered advisable to adopt the same level as for hydrogen selenide.

Scrupulous hygiene should be observed in tellurium processes. Workers should wear white coats, hand protection and simple gauze mask respiratory protection if handling the powder. Adequate sanitary facilities must be provided. Processes should not require hand grinding, and well-ventilated mechanical grinding stations should be used.

Tantalum

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Tantalum (Ta) is obtained from the ores tantalite and columbite, which are mixed oxides of iron, manganese, niobium and tantalum. Although they are considered rare elements, the earth’s crust contains about 0.003% of niobium and tantalum together, which are similar chemically and usually occur in combination.

The chief use of tantalum is in the production of electric capacitators. Tantalum powder is compacted, sintered and subjected to anodic oxidation. The film of oxide on the surface serves as an insulator, and upon introduction of an electrolyte solution, a high-performance capacitator is obtained. Structurally, tantalum is used where its high melting point, high density and resistance to acids are advantageous. The metal is employed widely in the chemical industry. Tantalum has also been used in rectifiers for railway signals, in surgery for suture wire and for bone repair, in vacuum tubes, furnaces, cutting tools, prosthetic appliances, fibre spinnerets and in laboratory ware.

Tantalum carbide is used as an abrasive. Tantalum oxide finds use in the manufacture of special glass with a high index of refraction for camera lenses.

Hazards

Metallic tantalum powder presents a fire and explosion hazard, although not as serious as that of other metals (zirconium, titanium and so on). The working of tantalum metal presents the hazards of burns, electric shock, and eye and traumatic injuries. Refining processes involve toxic and hazardous chemicals such as hydrogen fluoride, sodium and organic solvents.

Toxicity. The systemic toxicity of tantalum oxide, as well as that of metallic tantalum, is low, which is probably due to its poor solubility. It does, however, represent a skin, eye and respiratory hazard. In alloys with other metals such as cobalt, tungsten and niobium, tantalum has been attributed an aetiological role in hard-metal pneumoconiosis and in skin affections caused by hard-metal dust. Tantalum hydroxide was found to be not highly toxic to chick embryos, and the oxide was non-toxic to rats by intraperitoneal injection. Tantalum chloride, however, had an LD50 of 38 mg/kg (as Ta) while the complex salt K2TaF7 was about one-fourth as toxic.

Safety and Health Measures

In most operations, general ventilation can maintain the concentration of the dust of tantalum and its compounds below the threshold limit value. Open flames, arcs and sparks should be avoided in areas where tantalum powder is handled. If workers are regularly exposed to dust concentrations approaching the threshold limit level, periodic medical examinations, with emphasis on pulmonary function, are advisable. For operations involving fluorides of tantalum, as well as hydrogen fluoride, the precautions applicable to these compounds should be observed.

Tantalum bromide (TaBr5), tantalum chloride (TaCl5) and tantalum fluoride (TaF5) should be kept in tightly stoppered bottles which are plainly labelled and stored in a cool, ventilated place, away from compounds which are affected by acids or acid fumes. Personnel involved should be cautioned about their hazards.

Silver

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Silver (Ag) is found throughout the world, but most of it is produced in Mexico, the western United States, Bolivia, Peru, Canada and Australia. Much of it is obtained as a by-product from argentiferous lead, zinc and copper ores in which it occurs as the silver sulphide, argentite (Ag2S). It is also recovered during the treatment of gold ores and is an essential constituent of the gold telluride, calaverite ((AuAg)Te2).

Because pure silver is too soft for coins, ornaments, cutlery, plate and jewellery, silver is hardened by alloying with copper for all these applications. Silver is extremely resistant to acetic acid and, therefore, silver vats are used in the acetic acid, vinegar, cider and brewing industries. Silver is also used in busbars and windings of electrical plants, in silver solders, dental amalgams, high-capacity batteries, engine bearings, sterling ware and in ceramic paints. It is employed in brazing alloys and in the silvering of glass beads.

Silver finds use in the manufacture of formaldehyde, acetaldehyde and higher aldehydes by the catalytic dehydrogenation of the corresponding primary alcohols. In many installations, the catalyst consists of a shallow bed of crystalline silver of extremely high purity. An important use of silver is in the photography industry. It is the unique and instantaneous reaction of the halides of silver on exposure to light that makes the metal virtually indispensable for films, plates and photographic printing paper.

Silver nitrate (AgNO3) is used in photography, the manufacture of mirrors, silver plating, dyeing, colouring of porcelain, and etching ivory. It is an important reagent in analytical chemistry and a chemical intermediate. Silver nitrate is found in sympathetic and indelible inks. It also serves as a static inhibitor for carpets and woven materials and as a water disinfectant. For medical purposes silver nitrate has been used for the prophylaxis of ophthalmia neonatorum. It has been utilized as an antiseptic, an astringent, and in veterinary use for the treatment of wounds and local inflammations.

Silver nitrate is a powerful oxidizing agent and a fire hazard, in addition to being strongly caustic, corrosive and poisonous. In the form of dust or a solid it is dangerous to the eyes, causing burns of the conjunctiva, argyria and blindness.

Silver oxide (Ag2O) is used in the purification of drinking water, for polishing and colouring glass yellow in the glass industry, and as a catalyst. In veterinary medicine, it is used as an ointment or solution for general germicidal and parasiticidal purposes. Silver oxide is a powerful oxidizing material and a fire hazard.

Silver picrate ((O2N)3C6H2OAg·H2O) is used as a vaginal antimicrobial. In veterinary medicine it is used against granular vaginitis for cattle. It is highly explosive and poisonous.

Hazards

Silver exposure may lead to a benign condition called “argyria”. If the dust of the metal or its salts is absorbed, silver is precipitated in the tissues in the metallic state and cannot be eliminated from the body in this state. Reduction to the metallic state takes place either by the action of light on the exposed parts of the skin and visible mucous membranes, or by means of hydrogen sulphide in other tissues. Silver dusts are irritants and can lead to ulceration of the skin and nasal septum.

Occupations involving the risk of argyria can be divided into two groups:

- workers who handle a compound of silver, either the nitrate, fulminate or cyanide, which, broadly speaking, giving rise to generalized argyria from inhalation and ingestion of the silver salt concerned

- workers who handle metallic silver, small particles of which accidentally penetrate the exposed skin, giving rise to local argyria by a process equivalent to tattooing.

Generalized argyria is unlikely to occur at respirable silver concentrations in air of 0.01 mg/m3 or at oral cumulative doses lower than 3.8 g. Persons affected by generalized argyria are often called “blue men” by their fellow workers. The face, forehead, neck, hands and forearms develop a dark slatey-grey colour, uniform in distribution and varying in depth depending on the degree of exposure. Pale scars up to about 6 mm across may be found on the face, hands and forearms due to the caustic effects of silver nitrate. The fingernails are a deep chocolate-brown colour. The buccal mucosa is slatey-grey or bluish in colour. Very slight pigmentation may be detected in the covered parts of the skin. The toenails may show a slight bluish discolouration. In a condition called argyrosis conjunctivae, the colour of the conjunctivae varies from a slight grey to a deep brown, the lower palpebral portion being particularly affected. The posterior border of the lower lid, the caruncle and the plica semilunaris are deeply pigmented and may be almost black. Examination by means of the slit-lamp reveals a delicate network of faint grey pigmentation in the posterior elastic lamina (Descemet’s membrane) of the cornea, known as argyrosis corneae. In cases of long duration, argyrolentis is also found.

Where persons work with metallic silver, small particles may accidentally penetrate the exposed skin surface, giving rise to small pigmented lesions by a process equivalent to tattooing. This may occur in occupations involving the filing, drilling, hammering, turning, engraving, polishing, forging, soldering and smelting of silver. The left hand of the silversmith is more affected than the right, and the pigmentation occurs at the site of injuries from instruments. Many instruments, such as engraving tools, files, chisels and drills, are sharp and pointed and are liable to produce skin wounds. The piercing saw, an instrument resembling a fret saw, may break and run into the worker’s hand. If the file slips, the worker’s hand may be injured on the silver article; this is especially the case with the prongs of forks. A worker drawing silver wire through a hole in a silver draw-plate may get splinters of silver in his or her fingers. The pigmented points vary from tiny specks to areas 2 mm or more in diameter. They may be linear or rounded and in varying shades of grey or blue. The tattoo marks remain for life and cannot be removed. The use of gloves is usually impractical.

Safety and Health Measures

In addition to the engineering measures necessary to keep the airborne concentrations of silver fumes and dust as low as possible and in any case below the exposure limits, medical precautions for preventing argyria have been recommended. These include, in particular, the periodic medical examination of the eye, because the discolouration of the Descemet’s membrane is an early sign of the disease. Biological monitoring seems to be possible via the faecal excretion of silver. There is no recognized effective treatment of argyria. The condition seems to stabilize when exposure to silver is discontinued. Some clinical improvement has been achieved by use of chelating agents and intradermal injection of sodium thiosulphate or potassium ferrocyanide. Sun exposure should be avoided to prevent further discolouration of the skin.

The main incompatibilities of silver with acetylene, ammonia, hydrogen peroxide, ethyleneimine and a number of organic acids should be kept in mind in order to prevent fire and explosion hazards.

The most unstable silver compounds, such as silver acetylide, silver ammonium compounds, silver azide, silver chlorate, silver fulminate and silver picrate, should be kept in cool, well-ventilated places, protected from shock, vibration and contamination by organic or other readily oxidizable materials and away from light.

When working silver nitrate, personal protection should include the wearing of protective clothing to avoid skin contact as well as chemical safety goggles for the protection of the eyes where spillage may occur. Respirators should be available at workplaces in which engineering control cannot maintain an acceptable environment.

Selenium

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Selenium (Se) is found in rocks and soils all over the world. There are no true deposits of selenium anywhere, and it cannot economically be recovered directly. Various estimates for selenium in the Earth’s crust range from 0.03 to 0.8 ppm; the highest concentrations known are in native sulphur from volcanoes, which contains up to 8,350 ppm. Selenium does, however, occur together with tellurium in the sediments and sludges left from electrolytic copper refining. The chief world supplies are from the copper-refining industries of Canada, the United States and Zimbabwe, where the slimes contain up to 15% selenium.

The manufacture of selenium rectifiers, which convert alternating current to direct current, accounts for over half the world’s production of selenium. Selenium is also used for decolourizing green glass and for making ruby glass. It is an additive in the natural and synthetic rubber industries and an insecticide. Selenium is used for alloying with stainless steel and copper.

75Se is used for the radioactive scanning of the pancreas and for photostat and x-ray xerography. Selenium oxide or selenium dioxide (SeO2) is produced by burning selenium in oxygen, and it is the most widely used selenium compound in industry. Selenium oxide is employed in the manufacture of other selenium compounds and as a reagent for alkaloids.

Selenium chloride (Se2Cl2) is a dark brownish-red stable liquid which hydrolyses in moist air to give selenium, selenious acid and hydrochloric acid. Selenium hexafluoride (SeF6) is used as a gaseous electric insulator.

Hazards

The elemental forms of selenium are probably completely harmless to humans; its compounds, however, are dangerous and their action resembles that of sulphur compounds. Selenium compounds may be absorbed in toxic quantities through the lungs, intestinal tract or damaged skin. Many selenium compounds will cause intense burns of skin and mucous membranes, and chronic skin exposure to light concentrations of dust from certain compounds may produce dermatitis and paronychia.

The sudden inhalation of large quantities of selenium fumes, selenium oxide or hydrogen selenide may produce pulmonary oedema due to local irritant effects on the alveoli; this oedema may not set in for 1 to 4 hours after exposure. Exposure to atmospheric hydrogen selenide concentrations of 5 mg/m3 is intolerable. However, this substance occurs in only small amounts in industry (for example, due to bacterial contamination of selenium-contaminated gloves), although there have been reports of exposure to high concentrations following laboratory accidents.

Skin contact with selenium oxide or selenium oxychloride may cause burns or sensitization to selenium and its compounds, especially selenium oxide. Selenium oxychloride readily destroys skin on contact, causing third-degree burns unless immediately removed with water. However, selenium oxide burns are rarely severe and, if properly treated, heal without a scar.

Dermatitis due to exposure to airborne selenium oxide dust usually starts at the points of contact of the dust with the wrist or neck and may extend to contiguous areas of the arms, face and upper portions of the trunk. It usually consists of discrete, red, itchy papules which may become confluent on the wrist, where selenium dioxide is liable to penetrate between the glove and sleeve of the overall. Painful paronychia may also be produced. However, one more frequently sees cases of excruciatingly painful throbbing nail beds, due to the selenium dioxide penetrating under the free edge of the nails, in workers handling selenium dioxide powder or waste red selenium fume powder without wearing impermeable gloves.

Splashes of selenium oxide entering the eye may cause conjunctivitis if not treated immediately. Persons who work in atmospheres containing selenium dioxide dust may develop a condition known among the workers as “rose eye”, a pink allergy of the eyelids, which often become puffy. There is usually also a conjunctivitis of the palpebral conjunctiva but rarely of the bulbar conjunctiva.

The first and most characteristic sign of selenium absorption is a garlic odour of the breath. The odour is probably caused by dimethyl selenium, almost certainly produced in the liver by the detoxication of selenium by methylation. This odour will clear quickly if the worker is removed from exposure, but there is no known treatment for it. A more subtle and earlier indication than the garlic odour is a metallic taste in the mouth. It is less dramatic and is often overlooked by the workers. The other systemic effects are impossible to evaluate accurately and are not specific to selenium. They include pallor, lassitude, irritability, vague gastrointestinal symptoms and giddiness.

The possibility of liver and spleen damage in people exposed to high levels of selenium compounds deserves further attention. In addition, more studies of workers are needed to examine the possible protective effects of selenium against lung cancer.

Safety and Health Measures

Selenium oxide is the main selenium problem in industry since it is formed whenever selenium is boiled in the presence of air. All sources of selenium oxide or fumes should be fitted with exhaust ventilation systems with an air speed of at least 30 m/min. Workers should be provided with hand protection, overalls, eye and face protection, and gauze masks. Supplied-air respiratory protective equipment is necessary in cases where good extraction is not possible, such as in the cleaning of ventilation ducts. Smoking, eating and drinking at the workplace should be prohibited, and dining and sanitary facilities, including showers and locker rooms, should be provided at a point distant from exposure areas. Wherever possible, operations should be mechanized, automated or provided with remote control.

Ruthenium

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Ruthenium is found in the minerals osmiridium and laurite, and in platinum ores. It is a rare element comprising about 0.001 ppm of the Earth’s crust.

Ruthenium is used as a substitute for platinum in jewellery. It is utilized as a hardener for pen nibs, electrical contact relays and electrical filaments. Ruthenium is also used in ceramic colours and in electroplating. It acts as a catalyst in the synthesis of long-chain hydrocarbons. In addition, ruthenium has been used recently in treating eye uveal malignant melanomas.

Ruthenium forms useful alloys with platinum, palladium, cobalt, nickel and tungsten for better wear resistance. Ruthenium red (Ru3Cl6H42N4O2) or ruthenium oxychloride ammoniated is used as a microscopy reagent for pectin, gum, animal tissues and bacteria. Ruthenium red is an eye inflammatory agent.

Hazards

Ruthenium tetraoxide is volatile and irritating to the respiratory tract.

Some ruthenium electroplating complexes may be skin and eye irritants, but documentation of this is lacking. Ruthenium radioisotopes, chiefly 103Ru and 106Ru, occur as fission products in the nuclear fuel cycle. Since ruthenium may transform to volatile compounds (it forms numerous nitrogen complexes as noted above), there has been concern about its uptake in the environment. The significance of radio-ruthenium as a potential radiation hazard is still largely unknown.

Rhodium

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Rhodium is one of the rarest elements in the Earth’s crust (average concentration 0.001 ppm). It is found in small quantities associated with native platinum and some copper-nickel ores. It occurs in the minerals rhodite, sperrylite and iridosmine (or osmiridium).

Rhodium is used in corrosion-resistant electroplates for protecting silverware from tarnishing and in high-reflectivity mirrors for searchlights and projectors. It is also useful for plating optical instuments and for furnace winding. Rhodium serves as a catalyst for various hydrogenation and oxidation reactions. It is used for spinnerets in rayon production and as an ingredient in gold decorations on glass and porcelain.

Rhodium is alloyed with platinum and palladium to make very hard alloys for use in spinning nozzles.

Hazards

There have been no significant experimental data indicating health problems with rhodium, its alloys or its compounds in humans. Although toxicity is not established, it is necessary to handle these metals carefully. Contact dermatitis in a worker who prepared pieces of metal for plating with rhodium has been reported. The authors argue that the small number of reported cases of sensitization to rhodium may reflect the rarity of use rather than the safety of this metal. The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) has recommended a low threshold limit value for rhodium and its soluble salts, based on analogy with platinum. The ability of soluble salts of rhodium to give rise to allergic manifestations in humans has not been completely demonstrated.

Rhenium

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Rhenium (Re) is found in the combined state in platinum ores, gadolinite, molybdenite (MoS2) and columbite. It is found in some sulphide ores. It is a rare element making up about 0.001 ppm of the Earth’s crust.

Rhenium is used in electron tubes and in semiconductor applications. It is also used as a highly selective catalyst for hydrogenation and dehydrogenation. Rhenium-tagged antibodies have been used experimentally to treat adenocarcinomas of the colon, lung and ovary. Rhenium is used in medical instruments, in high-vacuum equipment, and in alloys for electrical contacts and thermocouples. It is also used for plating of jewellery.

Rhenium is alloyed with tungsten and molybdenum to improve their workability.

Hazards

Chronic toxic manifestations are not known. Some compounds, such as rhenium hexafluoride, are irritating to the skin and eye. In experimental animals, inhalation of rhenium dust causes pulmonary fibrosis. Rhenium VII sulphide ignites spontaneously in air and emits toxic fumes of oxides of sulphur when heated. Hexamethyl rhenium presents a serious explosion hazard and should be handled with extreme caution.

Rights and Duties: Workers' Perspective

Historically, people with disabilities have had tremendous barriers to entering the workforce, and those who became injured and disabled on the job have often faced job loss and its negative psychological, social and financial ramifications. Today, people with disabilities are still underrepresented in the workforce, even in countries with the most progressive civil rights and employment promotion legislation, and in spite of international efforts to address their situation.

Awareness has increased of the rights and needs of workers with disabilities and the concept of managing disability in the workplace. Workers’ compensation and social insurance programmes that protect income are common in industrialized countries. The increased costs related to operating such programmes have provided an economic basis for promoting the employment of people with disabilities and the rehabilitation of injured workers. At the same time, people with disabilities have become organized to demand their rights and integration into all aspects of community life, including the workforce.

Labour unions in many countries have been among those who have supported such efforts. Enlightened companies are recognizing the need to treat workers with disabilities equitably and are learning the importance of maintaining a healthy workplace. The concept of managing disability or dealing with disability issues in the workplace has emerged. Organized labour has been partly responsible for this emergence and continues to play an active role.

According to ILO Recommendation No. 168 concerning the vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons, “workers’ organizations should adopt a policy for the promotion of training and suitable employment of disabled persons on an equal footing with other workers”. The recommendation further suggests that workers’ organizations become involved in formulating national policies, cooperate with rehabilitation specialists and organizations, and foster the integration and vocational rehabilitation of disabled workers.

The purpose of this article is to explore the issue of disability in the workplace from the perspective of the rights and duties of workers and to describe the specific role that labour unions play in facilitating the on-the-job integration of people with disabilities.

In a healthy work environment, both the employer and the worker care about the quality of work, health and safety, and the fair treatment of all workers. Workers are hired on the basis of their abilities. Both workers and employers contribute to maintaining health and safety and, when an injury or disability does occur, they have the rights and duties to minimize the impact of the disability on the individual and the workplace. Although workers and employers may have different perspectives, by working in partnership they can effectively achieve goals related to maintaining a healthy, safe and fair workplace.

The term rights is often associated with legal rights determined by legislation. Many European countries, Japan and others have enacted quota systems requiring that a certain percentage of employees be persons with disabilities. Fines may be levied on employers who fail to meet the prescribed quota. In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in work and community life. Health and safety laws exist in most countries to protect workers from unsafe working conditions and practices. Workers’ compensation and social insurance programmes have been legislated to provide a variety of medical, social, and, in some instances, vocational rehabilitation services. Specific workers’ rights may also become part of negotiated labour agreements and therefore legally mandated.

A worker’s legal rights (and duties) related to disability and work will depend on the complexity of this legislative mix, which varies from country to country. For purposes of this article, workers’ rights are simply those legal or moral entitlements considered to be in the workers’ interest as they relate to productive activity in a safe and non-discriminating work environment. Duties refer to those obligations that workers have to themselves, other workers and their employers to contribute effectively to the productivity and safety of the workplace.

This article organizes worker rights and duties within the context of four key disability issues: (1) recruitment and hiring; (2) health, safety and the prevention of disability; (3) what happens when a worker becomes disabled, including rehabilitation and the return to work after injury; and (4) the total integration of the worker into the workplace and the community. Labour union activities related to these issues include: organizing and advocating for the rights of workers with disabilities through national legislation and other vehicles; ensuring and protecting rights by including them in negotiated labour agreements; educating union members and employers on disability issues and rights and responsibilities related to disability management; collaborating with management to further the rights and duties related to disability management; providing services to workers with disabilities to assist them in becoming integrated or more integrated into the workforce; and, when all else fails, engaging in resolving or litigating disputes, or fighting for legislative changes to protect rights.

Issue 1: Recruitment, Hiring and Employment Practices

While the legal obligations of labour unions may relate specifically to their members, unions traditionally helped to improve the working lives of all workers, including those with disabilities. This is a tradition that is as old as the labour movement itself. However, fair and equitable practices related to recruitment, hiring and employment practices take on special significance when the worker has a disability. Because of negative stereotypes as well as architectural, communication and other barriers related to disability, disabled job seekers and workers are often denied their rights or face discriminatory practices.

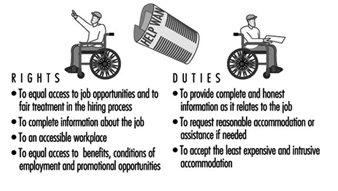

The following basic lists of rights (figure 1 to 4), although simply stated, have profound implications for equal access to employment opportunities by disabled workers. Disabled workers also have certain duties, as do all workers, to present themselves, including their interests, abilities, skills and workplace requirements, in an open and forthright manner.

Figure 1. Rights and duties: recruitment, hiring and employment practices

In the hiring process, applicants should be judged on their abilities and qualifications (figure 1). They need to have a full understanding of the job to evaluate their interest and ability to do the job. Further, once hired, all workers should be judged and evaluated according to their job performance, without bias based on factors not related to the job. They should have equal access to employment benefits and opportunities for advancement. When necessary, reasonable accommodations should be made so that an individual with a disability can perform the requisite job tasks. Job accommodations can be as simple as raising a workstation, making a chair available or adding a foot pedal.

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act not only prohibits discrimination against qualified workers (a qualified worker is one who has the qualifications and abilities to perform the essential functions of the job) based on disability, but also requires that employers make reasonable accommodation—that is, the employer provides a piece of equipment, changes non-essential job functions or makes some other adjustment that does not cause the employer undue hardship, so that the person with a disability can perform the essential functions of the job. This approach is designed to protect workers’ rights and make it “safe” to request accommodations. According to the US experience, most accommodations are relatively low in cost (less than US$50).

Rights and duties go hand in hand. Workers have a responsibility to notify their employer of a condition that may affect their ability to do the job, or that may affect their safety or that of others. Workers have a duty to represent themselves and their abilities in an honest manner. They should request a reasonable accommodation, if necessary, and accept that which is most appropriate for the situation, cost-effective and least intrusive to the workplace while still meeting their needs.

ILO Convention No. 159 concerning the vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons, and Recommendation No. 168 address these very rights and duties and their implications for workers’ organizations. Convention No.159 suggests that special positive measures may sometimes be necessary to ensure “effective equality of opportunity and treatment between disabled workers and other workers”. It adds that such measures “shall not be regarded as discriminating against other workers”. Recommendation No. 168 encourages the implementation of specific measures to create job opportunities, such as providing financial support to employers to make reasonable accommodations, and encourages labour organizations to promote such measures and provide advice about making such accommodations.

What labour unions can do

Union leaders typically have deep roots within the communities in which they operate and can be valuable allies in promoting the recruitment, hiring and continued employment of persons with disabilities. One of the first things they can do is to develop a policy statement on the employment rights of people with disabilities. Education of members and a plan of action to support the policy should follow. Labour unions can advocate rights for workers with disabilities on a broad scale by promoting, monitoring and supporting relevant legislative initiatives. In the workplace they should encourage management to develop policies and actions that remove barriers to employment for disabled workers. They can assist in developing appropriate job accommodations and, through negotiated labour agreements, protect and further the rights of disabled workers in all employment practices.

Organized labour can initiate programmes or cooperative efforts with employers, government ministries, non-governmental organizations, and companies to develop programmes that will result in increased recruitment and hiring of, and fair practices towards, people with disabilities. Representatives can sit on boards and lend their expertise to community-based organizations that work with people with disabilities. They can promote awareness among union members, and, in their role as employers, labour unions can set an example of fair and equitable hiring practices.

Examples of what labour unions are doing

In England, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) has taken an active role in promoting equal rights in employment for persons with disabilities, through published policy statements and active advocacy. It regards the employment of disabled people as an equal opportunities issue, and the experiences of disabled persons as not unlike those of other groups that have been discriminated against or excluded. The TUC supports existing quota legislation and advocates for levies (fines) on employers who fail to comply with the law.

It has published several related guides to support its activities and educate its members, including TUC Guidance: Trade Unions and Disabled Members, Employment of Disabled People, Disability Leave and Deaf People and Their Rights. Trade Unions and Disabled Members includes guidance about basic points that unions should consider when negotiating for disabled members. The Irish Congress of Trade Unions has produced a guide with similar intent, Disability and Discrimination in the Workplace: Guidelines for Negotiators. It provides practical steps to tackle workplace discrimination and to promote equality and access through negotiated labour agreements.

The Federation of German Trade Unions also has developed a comprehensive position paper stating its policy for integrative employment, its stance against discrimination and its commitment to use its influence to further its positions. It supports broad employment training and access to apprenticeships for disabled persons, addresses the double discrimination faced by disabled women, and advocates for union activities that support access to public transportation and integration into all aspects of society.

The Screen Actors Guild in the United States has approximately 500 members with disabilities. A statement on non-discrimination and affirmative action appears in its collective bargaining agreements. In a cooperative venture with the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, the Guild has met with national advocacy groups to develop strategies to increase the representation of people with disabilities in their respective industries. The International Union of United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America is another labour union that includes language in its collective bargaining agreements prohibiting discrimination based on disability. It also fights for reasonable accommodations for its members and provides regular training on disability and work issues. The United Steel Workers of America has included for years non-discrimination clauses in its collective bargaining agreements, and resolves disability discrimination complaints through a grievance process and other procedures.

In the United States, the passage and implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was, and continues to be, promoted by US-based labour unions. Even before passage of the ADA, many AFL-CIO member unions were actively involved in training their memberships on disability rights and awareness (AFL-CIO 1994). The AFL-CIO and other labour union representatives are carefully monitoring the implementation of the law, including litigation and alternative dispute resolution processes, to support the rights of workers with disabilities under the ADA and to ensure that their interests and the rights of all workers are fairly considered.

With passage of the ADA, labour unions have produced scores of publications and videos and organized training programmes and workshops to further educate their members. The Civil Rights Department of the AFL-CIO produced brochures and held workshops for their affiliated unions. The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers Center for Administering Rehabilitation and Education Services (IAM CARES), with support from the federal government, produced two videos and ten booklets for employers, people with disabilities and union personnel to inform them of their rights and responsibilities under the ADA. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) has a long-standing history of protecting the rights of workers with disabilities. With passage of the ADA, AFSCME updated its publications and other efforts and trained thousands of members and AFSCME staff on the ADA and workers with disabilities.

Although Japan has a quota and levy system in place, one Japanese labour union recognized that individuals who are mentally disabled are the most likely to be underrepresented in the labour force, especially among larger employers. It has been taking action. The Kanagawa Regional Council of the Japanese Electrical, Electronic and Information Union is working with the city of Yokohama to develop an employment support center. Its purpose will include training individuals who are mentally disabled and providing services to facilitate their placement and that of other disabled persons. Further, the union plans to establish a training centre that will provide disability awareness and sign-language training to union members, personnel managers, production supervisors and others. It will capitalize on good labour-employer relationships and engage business people in the management and activities of the centre. Initiated by the labour union, the project promises to be a model of collaboration between business, labour and government.

In the United States and Canada, labour unions have been working cooperatively and creatively with government and employers to facilitate the employment of people with disabilities through a programme called Projects with Industry (PWI). By matching labour union resources with government funding, IAM CARES and the Human Resources Development Institute (HRDI) of the AFL-CIO have been operating training and job placement programmes for individuals with disabilities regardless of their union affiliation. In 1968, HRDI began to function as the AFL-CIO’s employment and training arm by providing assistance to diverse ethnic groups, women and people with disabilities. In 1972, it began a programme with a specific focus on people with disabilities, to place them with employers who had labour agreements with national and international labour unions. As of 1995, more than 5,000 people with disabilities have been employed as a result of this activity. Since 1981, the IAM CARES programme, which operates in the Canadian and US labour markets, has enabled more than 14,000 individuals, most of whom are severely disabled, to find jobs. Both programmes provide professional assessment, counselling and job placement assistance through linkages with businesses and with government and labour union support.

In addition to providing direct services to workers with disabilities, these PWI programmes engage in activities that enhance public awareness of people with disabilities, promote cooperative labour-management action to foster employment and job retention, and provide training and consulting services to local unions and employers.

These are only some examples from around the world of activities that labour unions have taken to facilitate fairness in employment for workers with disabilities. It is fully in line with their broad goal to facilitate worker solidarity and to end all forms of discrimination.

Issue 2: Disability Prevention, Health and Safety

While securing safe working conditions is a hallmark of labour union activity in many countries, maintaining health and safety in the workplace has traditionally been an employer function. Typically, management has control over job design, tool selection, and decisions about processes and the work environment that affect safety and prevention. Yet, only someone who performs the tasks and procedures on a regular basis, under specific work conditions and demands, can fully appreciate the implications of procedures, conditions and hazards on safety and productivity.

Fortunately, enlightened employers recognize the importance of worker feedback, and as the organizational structure of the workplace is changing to increase worker autonomy, such feedback is more readily invited. Safety and prevention research also supports the need to involve the worker in job design, policy formulation and the implementation of programmes on health, safety and disability prevention.

Another trend, the sharp increase in workers’ compensation and other costs of job-related injury and disability, has led employers to examine prevention as a key component of the disability management effort. Prevention programmes should focus on the full range of stressors, including those of a psychological, sensory, chemical or physical nature, as well as on trauma, accidents and exposure to obvious hazards. Disability can result from repeated exposure to mild stressors or agents, rather than from a single incident. For example, some agents can cause or activate asthma; repeated or loud noises can lead to hearing loss; production pressure, such as piece-rate demands, can cause symptoms of psychological stress; and repetitive motions can lead to cumulative stress disorders (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome). Exposure to such stressors can exacerbate disabilities that already exist and make them more debilitating.

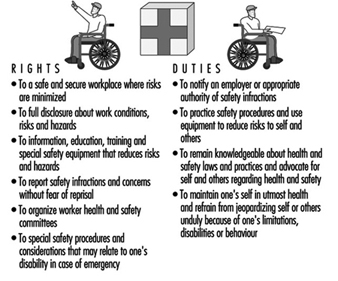

From a worker’s perspective, the benefits of prevention can never be overshadowed by compensation. Figure 2 lists some of the rights and responsibilities that workers have in relation to disability prevention in the workplace.

Figure 2. Rights and duties - health and safety

Workers have a right to the safest work environment possible and to the complete disclosure about risks and working conditions. Such knowledge is especially important to workers with disabilities who may need knowledge of certain conditions to determine whether they can perform the job functions without jeopardizing their health and safety or that of others.

Many jobs involve risks or dangers that cannot be fully removed. For example, construction jobs or those that deal with exposure to toxic substances have obvious, inherent risks. Other jobs, like data entry or sewing machine operation, seem relatively safe; however, repetitive motions or improper body mechanics can lead to disabilities. These risks can also be reduced.

All workers should be provided with necessary safety equipment and information on practices and procedures that reduce risk of injury or illness due to exposure to hazardous conditions, repetitive motions or other stressors. Workers must feel free to report/complain about safety practices, or to make suggestions to improve working conditions, without fear of losing their jobs. Workers should be encouraged to report an illness or disability, especially one that is caused or could be exacerbated by the work task or environment.

With regard to duties, workers have a responsibility to practice safety procedures that reduce risks to themselves and others. They must report unsafe conditions, advocate for health and safety issues, and be responsible regarding their health. For example, if a disability or illness places a worker or others at risk, the worker should remove him- or herself from the situation.

The field of ergonomics is emerging, with effective approaches to reducing disabilities incurred as a result of the manner in which the work is organized or performed. Ergonomics is basically the study of work. It involves fitting the job or task to the worker rather than vice versa (AFL-CIO 1992). Ergonomic applications have been used successfully to prevent disability in fields as diverse as agriculture and computers. Some ergonomic applications include flexible workstations that can be adapted to an individual’s height or other physical characteristics (e.g., adjustable office chairs), tools with handles to fit hand differences and simple changes in work routines to reduce repetitive motions or stress to certain parts of the body.

Increasingly, labour unions and employers recognize the need to extend health and safety programmes beyond the workplace. Even when disability or illness is not work-related, employers incur the costs of absenteeism, health insurance and perhaps rehiring and retraining. Further, some illnesses, such as alcoholism, drug addiction and psychological problems, can result in decreased worker productivity or increased vulnerability to on-the-job accidents and stress. For these and other reasons, many enlightened employers are engaging in education about health, safety and disability prevention on and off the job. Wellness programmes that address issues such as stress reduction, good nutrition, smoking cessation and AIDS prevention are being provided in the workplace by unions, management and through joint partnership efforts that may include the government as well.

Some employers provide wellness and employee assistance (counselling and referral) programmes to address these concerns. All of these prevention and health programmes are in the worker’s and employer’s best interests. For example, figures typically show savings-to-investment ratios between 3:1 and 15:1 for some health promotion and employee assistance programmes.

What can labour unions do?

Labour unions are in a unique position to use their leverage as representatives of workers to facilitate health, safety, disability prevention or ergonomics programmes in the workplace. Most prevention and ergonomics experts agree that worker participation and involvement in prevention policies and prescriptions increases the likelihood of their implementation and effectiveness (LaBar 1995; Westlander et al. 1995; AFL-CIO 1992). Labour unions can play a key role in establishing labour-management health and safety councils and ergonomics committees. They can lobby to promote legislation on workplace safety and work with management to establish joint safety committees, which can result in a substantial reduction in job-related accidents (Fletcher et al. 1992).

Labour unions need to educate their members about their rights, regulations and safe practices related to workplace safety and disability prevention on and off the job. Such programmes can become part of the negotiated labour agreement or union-based health and safety committees.

Further, in policy statements and labour agreements and through other mechanisms, labour unions can negotiate disability prevention measures and special conditions for those with disabilities. When a worker becomes disabled, especially if the disability is work-related, the union should support that worker’s right to accommodations, tools or reassignment to prevent exposure to stress or hazardous conditions that can increase the limitation. For example, those with occupationally induced hearing loss must be prevented from continued exposure to certain types of noise.

Examples of what labour unions are doing

The policy statement of the Federation of German Trade Unions concerning employees with disabilities specifically identifies the need to avoid health risks for workers with disabilities and to take measures to prevent them from incurring additional injury.

Under a negotiated labour agreement between the Boeing Aircraft Corporation and the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW), the IAM/Boeing Health and Safety Institute authorizes funding, develops pilot programmes and makes recommendations for improvements related to worker health and safety issues, and manages the return to work of industrially impaired workers. The Institute was established in 1989 and funded by a four cent per hour health and safety trust fund. It is operated by a Board of Directors that is composed of 50% management and 50% union representation.

The Disabled Forestry Workers Foundation of Canada is another example of a joint labour-management project. It evolved from a group of 26 employers, unions and other organizations that collaborated to produce a video (Every Twelve Seconds) to draw attention to the high accident rate among forestry workers in Canada. Now the Foundation focuses on health, safety, accident prevention and workplace models for reintegrating injured workers.

IAM CARES is engaged in an active programme of educating its members on safety issues, particularly in high-risk and hazardous jobs in the chemical industries, the construction trades and the steel industry. It conducts training for shop stewards and line workers, and encourages the formation of safety and health committees that are union-operated and independent of management.

The George Meany Center of the AFL-CIO, with a grant from the US Department of Labor, is developing educational materials on substance abuse to help union members and their families deal with alcohol and drug addictions.

The Association of Flight Attendants (AFA) has done some remarkable work in the area of AIDS and AIDS prevention. Volunteer members have developed the AIDS, Critical and Terminal Illness Awareness Project, which is educating members on AIDS and other life-threatening illnesses. Thirty-three of its locals have educated a total of 10,000 members about AIDS. It has established a foundation to administer funds to members who are also coping with a life-threatening disease.

Issue 3: When a Worker Becomes Disabled—Support, Rehabilitation, Compensation

In many countries, labour unions have fought for workers’ compensation, disability and other benefits related to on-the-job injury. Since one purpose of disability management programmes is to decrease the costs related to these benefits, it may be assumed that labour unions are not in favour of such programmes. In fact, this is not the case. Labour unions support rights related to job protection, early intervention in the provision of rehabilitation services and aspects of sound disability management practice. Disability management programmes that focus on reducing the worker’s suffering, address concerns about work loss, including its financial implications, and try to prevent short- and long-term disability are welcomed. Such programmes should return the worker to his or her job, if feasible, and provide accommodations when necessary. When it is not feasible, alternatives such as reassignment and retraining should be provided. As a last resort, long-term compensation and wage replacement should be guaranteed.

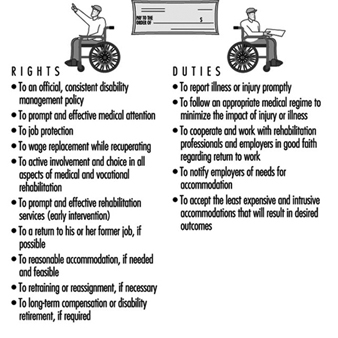

Fortunately, data suggest that disability management programmes can be structured to meet the needs and rights of the workers and still be cost effective for employers. As workers’ compensation costs have skyrocketed in industrialized countries, effective models that incorporate rehabilitation services have been developed and are being evaluated. Unions have a definitive role to play in developing such programmes. They need to promote and protect the rights listed in Figure 3 and educate workers about their duties.

Figure 3. Rights and duties: support, rehabilitation and compensation.

Most of the workers’ rights listed are part of standard return-to-work services for injured workers according to state-of-the-art rehabilitation techniques (Perlman and Hanson 1993). Workers have a right to prompt medical attention and to the assurance that their wages and jobs will be protected. Swift attention and early intervention are found to reduce the time away from work. Withholding benefits can result in refocusing efforts away from rehabilitation and returning to work, and into litigation and animosity towards the employer and the system. Workers need to understand what will happen if they become injured or disabled, and should have a clear understanding of company policy and legal protections. Unfortunately, some systems related to prevention, workers’ compensation and rehabilitation have been fragmented, open to abuse and confusing for those who depend on these systems at a vulnerable time.

Most trade unionists would agree that workers who become disabled gain little if they lose their jobs and their ability to work. Rehabilitation is a desired response to injury or disability and should include early intervention, comprehensive assessment and individualized planning with worker involvement and choice. Return-to-work plans may include returning to work gradually, with accommodation, at reduced hours or in reassigned positions until the worker is ready to return to optimal functioning.

Such accommodations, however, can interfere with the protected rights of workers in general, including those related to seniority. While trade unionists support and protect the rights of disabled workers to return to work, they seek solutions that do not interfere with negotiated seniority clauses or require restructuring of jobs in such a way that other workers are expected to assume new tasks or responsibilities for which they are not responsible or compensated. Collaboration and union involvement are necessary to resolve these issues when they arise, and such circumstances further illustrate the need for labour union involvement in the design and implementation of legislation, disability management and rehabilitation policies and programmes.

What labour unions can do

Labour unions need to be involved in national legislative planning committees related to disability, and in task forces which deal with such issues. Within corporate structures and the workplace, labour unions should help organize joint labour-management committees engaged in developing company-level disability management programmes, and should monitor individual outcomes. Unions can assist with return to work by suggesting accommodations, engaging the assistance of co-workers, and providing assurance to the injured worker.

Labour unions can work cooperatively with employers to develop model disability management programmes that assist workers and meet cost-containment goals. They can engage in research of worker needs, best practices and other activities to determine and protect worker interests. Worker education rights and responsibilities and needed actions are also critical to ensuring the best responses to injury and disability.

Examples of what labour unions have done

Some unions have been active in helping governments address the inadequacies of their systems related to on-the-job injuries and workers’ compensation. In 1988, responding to cost concerns related to injury compensation and to labour union concern over a lack of effective rehabilitation programmes, Australia passed the Commonwealth Employees Rehabilitation and Compensation Act, which provided a new coordination system for managing and preventing workplace illness and injuries of federal workers. The revised system is based on the premise that effective rehabilitation and return to work, if possible, is the most beneficial outcome for the worker and the employer. It incorporates prevention, rehabilitation and compensation into the system. Benefits and jobs are protected while the individual undergoes rehabilitation. Compensation includes wage replacement, medical and related expenses, and in certain instances limited lump sum payments. When individuals are unable to return to work they are adequately remunerated. Early results are demonstrating an 87% return-to-work rate. Success is attributed to many factors, including the collaborative involvement of all stakeholders, including labour unions, in the process.

The IAM/Boeing Health and Safety Institute, already mentioned, provides an example of a labour-management programme that was developed in one corporate setting. The model return-to-work programme was one of the first initiatives taken by the Institute because the needs of industrially injured workers were being neglected by fragmented service-delivery systems administered by federal, state, local and private rehabilitation agencies and programmes. After analysing data and conducting interviews, the union and the corporation set up a model programme that is felt to be in the best interests of both. The programme involves many of the rights already listed: early intervention; quick response with services and compensation requirements; intensive case management focused on return to work with accommodation, if needed; and regular evaluation of the programme’s outcomes and workers’ satisfaction.

Current satisfaction surveys indicate that management and injured workers have found the joint labour-management Return-to-Work Programme an improvement over existing services. The previous programme has been replicated at four additional Boeing plants and the joint programme is expected to become standard practice throughout the company. To date, more than 100,000 injured workers have received rehabilitation services through the programme.

The AFL-CIO’s HRDI programme also offers return-to-work rehabilitation services for workers injured on the job at companies with affiliated union representation. In partnership with Columbia University’s Workplace Center, it administered a demonstration programme called the Early Intervention Program, which sought to determine if early intervention can speed the process of getting workers, who are out of work because of short-term disability, back to the job. The programme returned 65% of participants to work and isolated several factors critical to success. Two findings are of particular significance to this discussion: (1)workers almost universally experience distress related to financial concerns; and (2) the programme’s union affiliation reduced suspicion and hostility.

The Disabled Forestry Workers Foundation of Canada developed a programme it calls the Case Management Model for Workplace Integration. Also using the joint union-management initiative, the programme rehabilitates and reintegrates disabled workers. It has published Industrial Disability Management: An Effective Economic and Human Resource Strategy to assist in the implementation of the model, built on partnership between employers, unions, government and consumers. Further, it has developed the National Institute of Occupational Disability and Research, involving labour, management, educators and rehabilitation professionals. The Institute is developing training programmes for human resource and union representatives that will lead to further implementation of its model.

Issue 4: Inclusion and Integration in the Community and the Workplace

In order for people with disabilities to become fully integrated in the workplace, they must first have equal access to all community resources that predispose and assist people to work (education and training opportunities, social services, etc.) and that give them access to the work environment (accessible housing, transportation, information, etc.). Many labour unions have recognized that people with disabilities are not able to participate in the workplace if they are excluded from full participation in community life. Further, once employed, people with disabilities may need special services and accommodations to be fully integrated or to maintain job performance. Equality in community life is a precursor to employment equity, and to fully address the issue of disability and work, the broader issue of human or civil rights must be considered.

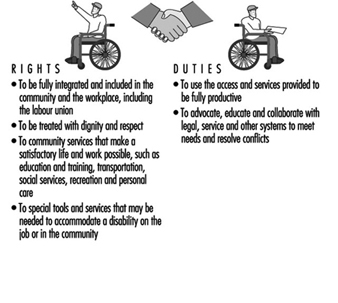

Labour unions have also recognized that to ensure employment equity, sometimes special services or accommodations may be required for job maintenance, and in the spirit of solidarity, may provide such services to their members or promote the provision of such accommodations and services. Figure 4 lists the rights and duties that recognize the need for full access to community life.

Figure 4. Rights and duties: inclusion and integration in the community and the workplace.

What unions can do

Labour unions can be direct agents of change in their communities by encouraging the total integration of people with disabilities in the workplace and community. Labour unions can reach out to workers with disabilities and the organizations that represent them, and collaborate to take positive action. The opportunities to exert political leverage and affect legislative change have been noted throughout this article, and they are fully in keeping with ILO Recommendation No. 168 and ILO Convention No. 159. Both stress the role of employers’ and workers’ organizations in the formulation of policies related to vocational rehabilitation, and their involvement in the implementation of policy and services.

Labour unions have a responsibility to represent the needs of all their workers. They should provide model services, programmes and representation within the labour union structure to include, accommodate and engage members with disabilities in all aspects of the organization. As some of the following examples will demonstrate, labour unions have used their members as a resource for raising funds, to serve as volunteers or to engage in direct services on the job and in the community to ensure that people with disabilities are fully included in community life and the workplace.

What unions have done

In Germany, a type of advocacy is legally mandated. According to the Severely Disabled Persons Act, any enterprise, including labour unions, that has five or more permanent employees, must have a person who is elected to the staff council as a representative of disabled employees. This representative ensures that the rights and concerns of disabled employees are addressed. Management is required to consult this representative in matters related to general recruitment as well as policy. As a result of this law, labour unions have become actively involved in disability issues.

The Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) has published and disseminated a Charter of Rights of People with Disabilities (1990), which is a list of 18 fundamental rights considered essential to the full equality of people with disabilities in the workplace and the community at large. It includes the rights to a barrier-free environment, housing, quality health care, education, training, employment and accessible transportation.

In 1946, the IAMAW began to help people with disabilities by establishing the International Guiding Eyes. This programme provides guide dogs and training in how to use them to blind and visually impaired individuals so that they can lead more independent and satisfying lives. Approximately 3,000 individuals from many countries have been helped. Part of the costs to operate the programme are borne by the contributions of union members.

The work of one Japanese labour union has been previously described. Its work was a natural evolution from the work of the Assembly of Trade Unions begun in the 1970s when a union member who had an autistic child requested labour union support to focus on the needs of children with disabilities. The Assembly established a foundation that was supported by the sale of matches and, later, boxes of tissues, by union members. The foundation started a counselling service and a telephone hotline to help parents cope with the challenges of raising a disabled child in a segregated society. As a result, parents became organized and lobbied the government to address accessibility (railways were pressured to improve accessibility, a process that continues today) and to provide educational training and upgrade other services. Summer activities and festivals were sponsored, as well as national and international tours, to foster understanding of disability issues.

After twenty years, when the children grew up, their needs for recreation and education became needs for vocational skills and employment. A vocational experience programme for youth with disabilities was developed and has been in effect for several years. The unions requested companies to provide work experiences for second-year high school students with disabilities. It was out of this programme that the need for the Employment Support Center, noted under Issue 1, became apparent.

Many unions provide extra support services to people with disabilities on the job to assist them in maintaining employment. The Japanese labour unions use on-the-job volunteers to support young people in work-experience programmes with companies that have union representation. IAM CARES in the United States and Canada uses a buddy system to match new employees who have disabilities with a union member who serves as a mentor. IAM CARES also has sponsored supported employment programmes with Boeing and other companies. Supported employment programmes provide job coaches to assist those with the most severe disabilities in learning their jobs and maintaining their performance at productive levels.

Some labour unions have established subcommittees or task forces composed of disabled workers, to ensure that the rights and needs of disabled members are fully represented within the union structure. The American Postal Workers Union is an excellent example of such a task force and the wide implications it can have. In the 1970s, the first deaf shop steward was appointed. Since 1985, several conferences have been held just for hearing-impaired members. These members also serve on negotiating teams to resolve job accommodation and disability management issues. In 1990, the task force worked with the postal service to develop an official stamp depicting the words “I love you” in a hand sign.

Conclusions

Unions, at their most basic level, are about people and their needs. Since the earliest days of labour union activity, unions have done more than fight for fair wages and optimal working conditions. They have sought to improve the quality of life and to maximize opportunities for all workers, including those with disabilities. Although the union perspective emanates from the workplace, the union influence is not limited to enterprises where negotiated labour agreements exist. As many examples in this article demonstrate, labour unions can also affect the larger social environment through a variety of activities and initiatives that are aimed at eliminating discrimination and inequities towards people with disabilities.

While unions, employers, government entities, vocational rehabilitation representatives and men and women with disabilities may have different perspectives, they should share the desire for a healthy and productive workplace. Unions are in a unique position to bring these groups together on common ground, and thereby play a key role in improving the lives of people with disabilities.

Platinum

Gunnar Nordberg

Occurrence and Uses

Platinum (Pt) occurs in native form and in a number of mineral forms, including sperrylite (PtAs2), cooperite (Pt,Pd)S and braggite (Pt,Pd,Ni)S. Platinum is sometimes found with palladium as the arsenide and selenide. The concentration of platinum in the Earth’s crust is 0.005 ppm.