Industrialized Countries and Occupational Health and Safety

Overview

Economic activity, as expressed by per capita gross national product (GNP), differs substantially between developing countries and industrialized countries. According to a ranking by the World Bank, the GNP of the country heading the list is approximately fifty times that of the country at the bottom. The share of the world’s total GNP by the member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is almost 20%.

OECD member countries account for almost one-half the world’s total energy consumption. Carbon dioxide emissions from the top three countries account for 50% of the earth’s total burden; these countries are responsible for major global pollution problems. However, since the two oil crises in 1973 and 1978, industrialized countries have been making efforts to save energy by replacing old processes with more efficient types. Simultaneously, heavy industries consuming much energy and involving much heavy labour and exposure to hazardous or dangerous work have been moving from these countries to less industrialized countries. Thus, the consumption of energy in developing countries will increase in the next decade and, as this occurs, problems related to environmental pollution and occupational health and safety are expected to become more serious.

In the course of industrialization, many countries experienced ageing of the population. In the major industrialized nations, those 65 years or older account for 10 to 15% of the total population. This is a significantly higher proportion than that of developing countries.

This disparity reflects the lower reproduction rate and lower mortality rates in the industrialized countries. For example, the reproduction rate in industrialized countries is less than 2%, whereas the highest rates, more than 5%, are seen in African and Middle Eastern countries and 3% or more is common in many developing countries. The increased proportion of female workers, ranging from 35 to 50% of the work force in industrialized countries (it is usually under 30% in less industrialized countries), may be related to the decreased number of children.

Greater access to higher education is associated with a higher proportion of professional workers. This is another significant disparity between industrialized and developing countries. In the latter, the proportion of professional workers has never exceeded 5%, a figure in sharp contrast to the Nordic countries, where it ranges from 20 to 30%. The other European and the North American countries fall in between, with professionals making up more than 10% of the workforce. Industrialization depends primarily on research and development, work that is associated more with excess stress or strain in contrast to the physical hazards characteristic of much of the work in developing countries.

Current Status of Occupational Health and Safety

The economic growth and the changes in the structure of major industries in many industrializing countries has been associated with reduced exposure to hazardous chemicals, both in terms of the levels of exposure and the numbers of workers exposed. Consequently, instances of acute intoxication as well as typical occupational diseases are diminishing. However, the delayed or chronic effects due to exposures many years previously (e.g., pneumoconiosis and occupational cancer) are still seen even in the most industrialized countries.

At the same time, technical innovations have introduced the use of many newly created chemicals into industrial processes. In December, 1982, to guard against the hazards presented by such new chemicals, OECD adopted an international recommendation on a Minimum Premarketing Set of Data for Safety.

Meanwhile, life in the workplace and in the community have continued to become more stressful than ever. The proportions of troubled workers with problems related to or resulting in alcohol and/or drug abuse and absenteeism have been on the rise in many industrialized countries.

Work injuries have been decreasing in many industrialized countries largely due to progress in safety measures at work and the extensive introduction of automated processes and equipment. The reduction of the absolute number of workers engaging in more dangerous work due to the change of industrial structure from heavy to light industry is also an important factor in this decrease. The number of workers killed in work accidents in Japan decreased from 3,725 in 1975 to 2,348 in 1995. However, analysis of the time trend indicates that the rate of decrease has been slowing over the past ten years. The incidence of work injuries in Japan (including fatal cases) fell from 4.77 per one million working hours in 1975 to 1.88 in 1995; a rather slower decrease was seen in the years 1989 to 1995. This bottoming out of the trend toward reductions in industrial accidents has also been seen in some other industrialized countries; for example, the frequency of work injuries in the United States has not improved for more than 40 years. In part, this reflects the replacement of classic work accidents which can be prevented by various safety measures, by the new types of accidents caused by the introduction of automated machines in these countries.

The ILO Convention No. 161 adopted in 1985 has provided an important standard for occupational health services. Even though its scope includes both developing and developed countries, its fundamental concepts are based on existing programmes and experience in industrialized countries.

The basic framework of an occupational health service system of a given country is generally described in legislation. There are two major types. One is represented by the United States and the United Kingdom, in which the legislation stipulates only the standards to be satisfied. Achievement of the goals is left to the employers, with the government providing information and technical assistance on request. Verifying compliance with the standards is a major administrative responsibility.

The second type is represented by the legislation of France, which not only prescribes the goals but also details the procedures for reaching them. It requires employers to provide specialized occupational health services to the employees, using physicians who have become certified specialists, and it requires service institutions to offer such services. It specifies the number of workers to be covered by the appointed occupational physician: in worksites without a hazardous environment more than 3,000 workers can be covered by a single physician, whereas the number is smaller for those exposed to defined hazards.

Specialists working in the occupational health setting are expanding their target fields in the industrialized countries. Physicians have become more specialized in preventive and health management than ever before. In addition, occupational health nurses, industrial hygienists, physiotherapists and psychologists are playing important roles in these countries. Industrial hygienists are popular in the United States, while environment measurement specialists are much more common in Japan. Occupational physiotherapists are rather specific to the Nordic countries. Thus, there are some differences in the kind and distribution of existing specialists by region.

Establishments with more than several thousand workers usually have their own independent occupational health service organization. Employment of specialists including those other than occupational physicians, and provision of the minimum facilities necessary to provide comprehensive occupational health services, are generally feasible only when the size of the workforce exceeds that level. Provision of occupational health services for small establishments, especially for those with only a few workers, is another matter. Even in many industrialized countries, occupational health service organizations for smaller-scale establishments have not yet been established in a systematic manner. France and some other European countries have legislation articulating minimum requirements for the facilities and services to be provided by occupational health service organizations, and each enterprise without its own service is required to contract with one such organization to provide the workers with the prescribed occupational health services.

In some industrialized countries, the content of the occupational health programme is focused mainly on preventive rather than on curative services, but this is often a matter of debate. In general, countries with a comprehensive community health service system tend to limit the area to be covered by the occupational health programme and regard treatment as a discipline of community medicine.

The question of whether periodic health check-ups should be provided for the ordinary worker is another matter of debate. Despite the view held by some that check-ups involving general health screening have not proven to be beneficial, Japan is one of a number of countries in which a requirement that such health examinations be offered to employees has been imposed on employers. Extensive follow-up, including continuing health education and promotion, is strongly recommended in such programmes, and longitudinal record keeping on an individual basis is considered indispensable for achieving its goals. Evaluation of such programmes requires long-term follow-up.

Insurance systems covering medical care and compensation for workers involved in work-related injuries or diseases are found in almost all industrialized countries. However, there is much variation among these systems with regard to management, coverage, premium payment, types of benefits, extent of the commitment to prevention, and the availability of technical support. In the United States, the system is independent in each state, and private insurance companies play a large role, whereas in France the system is managed completely by the government and incorporated extensively into the occupational health administration. Specialists working for the insurance system often play an important part in technical assistance for the prevention of occupational accidents and diseases.

Many countries provide a post-graduate educational system as well as residency training courses in occupational health. The doctorate is usually the highest academic degree in occupational health, but specialist qualification systems also exist.

The schools of public health play an important part in the education and training of occupational health experts in the United States. Twenty-two of the 24 accredited schools provided occupational health programmes in 1992: 13 provided programmes in occupational medicine and 19 had programmes in industrial hygiene. The occupational health courses offered by these schools do not necessarily lead to an academic degree, but they are closely related to the accreditation of specialists in that they are among the qualifications needed to qualify for the examinations that must be passed in order to become a diplomat of one of the boards of specialists in occupational health.

The Educational Resource Program (ERC), funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), has been supporting residency programmes at these schools. The ERC has designated 15 schools as regional centres for the training of occupational health professionals.

It is often difficult to arrange education and training in occupational health for physicians and other health professionals who are already involved in primary health care services in the community. A variety of distance-learning methods have been developed in some countries—for example, a correspondence course in the United Kingdom and a telephone communication course in New Zealand, both of which have received good evaluations.

Factors Influencing Occupational Health and Safety

Prevention at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels should be a basic aim of the occupational safety and health programme. Primary prevention through industrial hygiene has been highly successful in decreasing the risk of occupational disease. However, once a level sufficiently below the permissible standard has been reached, this approach becomes less effective, especially when cost/benefit is taken into consideration.

The next step in primary prevention involves biological monitoring, focusing on differences in individual exposure. Individual susceptibility is also important at this stage. Determination of fitness to work and allocation of reasonable numbers of workers to particular operations are receiving increasing attention. Ergonomics and various mental health techniques to reduce stress at work represent other indispensable adjuncts in this stage.

The goal of preventing worksite exposures to hazards has been gradually overshadowed by that of health promotion. The final goal is to establish self-management of health. Health education to achieve this end is regarded as a major area to be covered by specialists. The Japanese government has launched a health promotion programme entitled “Total Health Promotion Plan”, in which the training of specialists and financial support for each worksite programme are major components.

In most industrialized countries, labour unions play an important part in occupational health and safety efforts from the central to peripheral levels. In many European countries union representatives are officially invited to be members of committees responsible for deciding the basic administrative directions of the programme. The mode of labour commitment in Japan and the United States is indirect, while the government ministry or department of labour wields administrative power.

Many industrialized countries have a workforce which comes from outside the country both officially and unofficially. There are various problems presented by these immigrant workers, including language, ethnic and cultural barriers, educational level, and poor health.

Professional societies in the field of occupational health play an important part in supporting training and education and providing information. Some academic societies issue specialist certification. International cooperation is also supported by these organizations.

Projections for the Future

Coverage of workers by specialized occupational health services is still not satisfactory except in some European countries. As long as provision of the service remains voluntary, there will be many uncovered workers, especially in small enterprises. In high-coverage countries like France and some Nordic countries, insurance systems play an important part in the availability of financial support and/or technical assistance. To provide services for small establishments, some level of commitment by social insurance may be necessary.

Occupational health service usually proceeds faster than community health. This is especially the case in large companies. The result is a gap in services between occupational and community settings. Workers receiving better health service throughout working life frequently experience health problems after retirement. Sometimes, the gap between large and small establishments cannot be ignored as, for example, in Japan, where many senior workers continue to work in smaller companies after mandatory retirement from large companies. The establishment of a continuity of services between these different settings is a problem that will inevitably have to be addressed in the near future.

As the industrial system becomes more complicated, control of environmental pollution becomes more difficult. An intensive anti-pollution activity in a factory may simply result in moving the pollution source to another industry or factory. It may also lead to the export of the factory with its pollution to a developing country. There is a growing need for integration between occupational health and environmental health.

Occupational Health Trends in Development

This article discusses some of the currently specific concerns and issues relating to occupational health in the developing world and elsewhere. The general technical subjects common to both the developed and the developing world (e.g., lead and pesticides) are not dealt with in this article as they have been addressed elsewhere in the Encyclopaedia. In addition to the developing countries, some of the emerging occupational health issues of the Eastern European nations too have been addressed separately in this chapter.

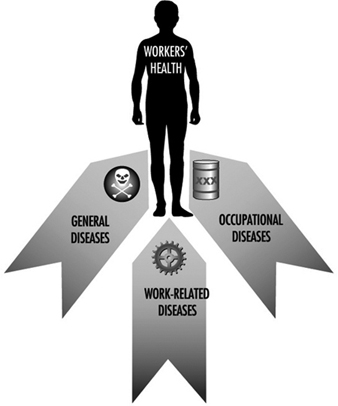

It is estimated that by the year 2000 eight out of ten workers in the global workforce will be from the developing world, demonstrating the need to focus on the occupational health priority needs of these nations. Furthermore, the priority issue in occupational health for these nations is a system for the provision of health care to their working population. This need fits in with the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of occupational health, which expresses the concern for the total health of the worker and is not confined merely to occupational diseases. As shown in figure 1 the worker may be affected by the general diseases of the community which may occur among workers, such as malaria, as well as multi-factorial work-related diseases, in which work may contribute to or aggravate the condition. Examples are cardiovascular diseases, psychosomatic illnesses and cancers. Finally, there are the occupational diseases, in which exposure at the workplace is essential to causation, such as with lead poisoning, silicosis or noise-induced deafness.

Figure 1. Categories of disease affecting workers

The WHO philosophy recognizes the two-way relationship between work and health, as represented in figure 2. Work may have an adverse or beneficial effect on health, while the health status of the worker has an impact on work and productivity.

Figure 2. Two-way relationship between work and health

A healthy worker contributes positively to productivity, quality of products, work motivation and job satisfaction, and thereby to the overall quality of life of individuals and society, making health at work an important policy goal in national development. To achieve this goal, the WHO has recently proposed the Global Strategy on Occupational Health for All (WHO 1995), in which the ten priority objectives are:

- strengthening of international and national policies for health at work and developing the necessary policy tools

- development of healthy work environment

- development of healthy work practices and promotion of health at work

- strengthening of occupational health services

- establishment of support services for occupational health

- development of occupational health standards based on scientific risk assessment

- development of human resources for occupational health

- establishment of registration and data systems, development of information services for experts, effective transmission of data and raising of public awareness through public information

- strengthening of research

- development of collaboration in occupational health and with other activities and services.

Occupational Health and National Development

It is useful to view occupational health in the context of national development as the two are intimately linked. Every nation wishes to be in a state of advanced development, but it is the countries of the developing world which are most anxious—almost demanding—for rapid development. More often than not, it is the economic advantages of such development which are most sought after. True development is, however, generally understood to have a wider meaning and to encompass the process of improving the quality of human life, which in turn includes aspects of economic development, of improving self-esteem and of increasing people’s freedom to choose. Let us examine the impact of this development on the health of the working population, i.e., development and occupational health.

While the global gross domestic product (GDP) has remained almost unchanged for the period 1965-89, there has been an almost tenfold increase in the GDP of the developing world. But this rapid economic growth of the developing world must be seen in the context of overall poverty. With the developing world constituting three quarters of the world’s population, it accounts for only 15% of the global domestic product. Taking Asia as a case in point, all of the countries of Asia except for Japan are categorized as part of the developing world. But it needs to be recognized that there is no uniformity of development even among the developing nations of Asia. For instance, today, countries and areas such as Singapore, Republic of Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan (China) have been categorized as newly industrialized countries (NICs). Though arbitrary, this implies a transition stage from developing country status to industrialized nation status. However, it must be recognized that there are no clear criteria defining a NIC. Nevertheless, some of the salient economic features are high sustained growth rates, diminishing income inequality, an active government role, low taxes, underdeveloped welfare state, high savings rate and an economy geared to exports.

Health and Development

There exists an intimate relationship between health, development and the environment. Rampant and uncontrolled development measures purely in terms of economic expansion could, under certain circumstances, be considered to have an adverse impact on health. Usually, though, there exists a strong positive relationship between a nation’s economic status and health as indicated by life expectancy.

As much as development is positively linked to health, it is not adequately recognized that health is a positive force driving development. Health must be considered to be more than a consumer item. Investing in health increases the human capital of a society. Unlike roads and bridges, whose investment values dwindle as they deteriorate over time, the returns on health investments can generate high social returns for a lifetime and well into the next generation. It should be recognized that any health impairment that the worker may suffer is likely to have an adverse effect on work performance, a matter of considerable interest particularly to nations in the throes of rapid development. For instance, it is estimated that poor occupational health and reduced working capacity of workers may cause an economic loss of up to 10 to 20% of gross national product (GNP). Furthermore, the World Bank estimates that two-thirds of occupationally determined disability adjusted life years (DALYS) could be prevented by occupational health and safety programmes. As such, the provision of an occupational health service should not be viewed as a national expense to be avoided, but rather as one that is necessary for the national economy and development. It has been observed that a high standard of occupational health correlates positively with a high GNP per capita (WHO 1995). The countries investing most in occupational health and safety show the highest productivity and strongest economies, while countries with the lowest investment have the lowest productivity and the weakest economies. Globally, each worker is said to contribute US$9,160 to the annual domestic product. Evidently the worker is the engine of the national economy and the engine needs to be kept in good health.

Development results in many changes to the social fabric, including the pattern of employment and changes in the productivity sectors. In the early stages of development, agriculture contributes extensively to national wealth and the workforce. With development, the role of agriculture begins to decline and the contribution of the manufacturing sector to national wealth and the workforce becomes dominant. Finally, there comes a situation where the service sector becomes the largest income source, as in the advanced economies of industrialized countries. This is clearly evident when a comparison is made between the group of NICs and the group of Association of Southeast Asian (ASEAN) nations. The latter could be categorized as middle income nations of the developing world, while the NICs are countries straddling the developing and the industrialized worlds. Singapore, a member of ASEAN, is also a NIC. The ASEAN nations, though deriving approximately a quarter of their gross domestic product from agriculture, have almost half of their GDP drawn from industry and manufacturing. The NICs, on the other hand, particularly Hong Kong and Singapore, have approximately two-thirds of their GDP from the service sector, with very little or none from agriculture. The recognition of this changing pattern is important in that occupational health services must respond to the needs of each nation’s workforce depending on their stage of development (Jeyaratnam and Chia 1994).

In addition to this transition in the workplace, there also occurs a transition in disease patterns with development. A change in disease patterns is seen with increasing life expectancy, with the latter indicative of increasing GDP. It is seen that with development or an increase in life expectancy, there is a large decrease in death from infectious diseases while there are large increases in deaths from cardiovascular diseases and cancers.

Occupational Health Concerns and Development

The health of the workforce is an essential ingredient for national development. But, at the same time, adequate recognition of the potential pitfalls and dangers of development must be recognized and safeguarded against. The potential damage to human health and the environment consequent to development must not be ignored. Planning for development can avert and prevent harms associated therewith.

Lack of adequate legal and institutional structure

The developed nations evolved their legal and administrative structure to keep pace with their technological and economic advancements. In contrast, the countries of the developing world have access to the advanced technologies from the developed world without having developed either legal or administrative infrastructure to control their adverse consequences to the workforce and the environment, causing a mismatch between technological development and social and administrative development.

Further, there is also careless disregard of control mechanisms for economic and/or political reasons (e.g., the Bhopal chemical disaster, where an administrator’s advice was overruled for political and other reasons). Often, the developing countries will adopt standards and legislation from the developed countries. There is, however, a lack of trained personnel to administer and enforce them. Furthermore, such standards are often inappropriate and have not taken into account differences in nutritional status, genetic predisposition, exposure levels and work schedules.

In the area of waste management, most developing countries do not have an adequate system or a regulatory authority to ensure proper disposal. Although the absolute amount of waste produced may be small in comparison to developed countries, most of the wastes are disposed of as liquid wastes. Rivers, streams and water sources are severely contaminated. Solid wastes are deposited on land sites without proper safeguards. Furthermore, developing countries have often been the recipients of hazardous wastes from the developed world.

Without proper safeguards in hazardous waste disposal, the effects of environmental pollution will be seen for several generations. Lead, mercury and cadmium from industrial waste are known to contaminate water sources in India, Thailand and China.

Lack of proper planning in siting of industries and residential areas

In most countries, the planning of industrial areas is undertaken by the government. Without the presence of proper regulations, residential areas will tend to congregate around such industrial areas because the industries are a source of employment for the local population. Such was the case in Bhopal, India, as discussed above, and the Ulsan/Onsan industrial complex of the Republic of Korea. The concentration of industrial investment in the Ulsan/Onsan complex brought about a rapid influx of population to Ulsan City. In 1962, the population was 100,000; within 30 years, it increased to 600,000. In 1962, there were 500 households within the boundaries of the industrial complex; in 1992, there were 6,000. Local residents complained of a variety of health problems that are attributable to industrial pollution (WHO 1992).

As a result of such high population densities in or around the industrial complexes, the risk of pollution, hazardous wastes, fires and accidents is greatly multiplied. Furthermore, the health and future of the children living around these areas are in real jeopardy.

Lack of safety-conscious culture among workers and management

Workers in developing countries are often inadequately trained to handle the new technologies and industrial processes. Many workers have come from a rural agricultural background where the pace of work and type of work hazards are completely different. The educational standards of these workers are often much lower as compared to the developed countries. All these contribute to a general state of ignorance on health risks and safe workplace practices. The toy factory fire in Bangkok, Thailand, discussed in the chapter Fire, is an example. There were no proper fire safety precautions. Fire exits were locked. Flammable substances were poorly stored and these had blocked all the available exits. The end result was the worst factory fire in history with a death toll of 187 and another 80 missing (Jeyaratnam and Chia 1994).

Accidents are often a common feature because of a lack of commitment of management to the health and safety of the workers. Part of the reason is the lack of skilled personnel in maintaining and servicing industrial equipment. There is also a lack of foreign exchange, and government import controls make it difficult to obtain proper spare parts. High turnover of workers and the large readily available labour market also make it unprofitable for management to invest heavily in workers’ training and education.

Transfer of hazardous industries

Hazardous industries and unsuitable technologies in the developed countries are often transferred to the developing countries. It is cheaper to transfer the entire production to a country where the environmental and health regulations are more easily and cheaply met. For example, industries in the Ulsan/Onsan industrial complex, Republic of Korea, were applying emission control measures in keeping with local Korean legislation. These were less stringent than in the home country. The net effect is a transfer of potentially polluting industries to the Republic of Korea.

High proportion of small-scale industries

Compared to the developed countries, the proportion of small-scale industries and the proportion of workers in these industries are higher in the developing countries. It is more difficult in these countries to maintain and enforce compliance in occupational health and safety regulations.

Lower health status and quality of health care

With economic and industrial development, new health hazards are introduced against a backdrop of poor health status of the population and a less than adequate primary health care system. This will further tax the limited health care resources.

The health status of workers in the developing countries is often lower compared to that of workers in developed countries. Nutritional deficiencies and parasitic and other infectious diseases are common. These can increase the susceptibility of the worker to developing occupational diseases. Another important observation is the combined effect of workplace and non-workplace factors on the health of the worker. Workers with nutritional anaemias are often very sensitive to very low levels of inorganic lead exposure. Significant anaemias are often seen with blood lead levels of around 20 μg/dl. A further example is seen among workers with congenital anaemias like thalassaemias, the carrier rate for which in some countries is high. It has been reported that these carriers are very sensitive to inorganic lead, and the time taken for the haemoglobin to return to normal is longer than in non-carriers.

This situation reveals a narrow dividing line between traditional occupational diseases, work-related diseases and the general diseases prevalent in the community. The concern in the countries of the developing world should be for the overall health of all people at work. In order to achieve this objective, the nation’s health sector must accept responsibility for organizing a programme of work for the provision of health care services for the working population.

It must also be recognized that the labour sector has an important role in ensuring the safety of the work environment. In order to achieve this, there is a need to review legislation so that it covers all workplaces. It is inadequate to have legislation limited to factory premises. Legislation should not only provide a secure and safe workplace, but also ensure the provision of regular health services to the workers.

Thus it would be evident that two important sectors, namely the labour sector and the health sector, have important roles to play in occupational health. This recognition of the intersectoriality of occupational health is an extremely important ingredient for the success of any such programme. In order to achieve proper coordination and cooperation between these two sectors, it is necessary to develop an intersectorial coordinating body.

Finally, legislation for the provision of occupational health services and ensuring the safety of the workplace is fundamental. Again, many Asian countries have recognized this need and have such legislation today, although its implementation may be wanting to some extent.

Conclusions

In developing countries, industrialization is a necessary feature of economic growth and development. Although industrialization can bring about adverse health effects, the accompanying economic development can have many positive effects on human health. The aim is to minimize the adverse health and environmental problems and maximize the benefits of industrialization. In the developed countries, experience from the adverse effects of the Industrial Revolution has led to regulation of the pace of development. These countries have generally coped fairly well and had the time to develop all the necessary infrastructure to control both health and environmental problems.

The challenge today for the developing countries who, because of international competition, do not have the luxury of regulating their pace of industrialization, is to learn from the mistakes and lessons of the developed world. On the other hand, the challenge for the developed countries is to assist the developing countries. The developed countries should not take advantage of the workers in developing countries or their lack of financial capacity and regulatory mechanisms because, at the global level, environmental pollution and health problems do not respect political or geographical boundaries.

International Code of Ethics for Occupational Health Professionals

International Commission on Occupational Health

Introduction

Codes of ethics for occupational health professionals, as distinct from Codes of ethics for medical practitioners, have been adopted during the past ten years by a number of countries. There are several reasons for the development of interest in ethics in occupational health at the national and international levels.

One is the increased recognition of the complex and sometimes competing responsibilities of occupational health and safety professionals towards the workers, the employers, the public, the competent authority and other bodies (public health and labour authorities, social security and judicial authorities). Another reason is the increasing number of occupational health and safety professionals as a result of the compulsory or voluntary establishment of occupational health services. Yet another factor is the development of a multi-disciplinary and intersectoral approach in occupational health which implies an increasing involvement in occupational health services of specialists who belong to various professions.

For the purpose of this Code, the expression “occupational health professionals” is meant to include all those who by profession carry out occupational safety and health activities, provide occupational health services or who are involved in occupational health practice, even if this happens only occasionally. A wide range of disciplines is concerned with occupational health since it is at an interface between technology and health involving technical, medical, social and legal aspects. Occupational health professionals include occupational health physicians and nurses, factory inspectors, occupational hygienists and occupational psychologists, specialists involved in ergonomics, in accident prevention and in the improvement of the working environment as well as in occupational health and safety research. The trend is to mobilise the competence of these occupational health professionals within the framework of a multi-disciplinary approach which may sometimes take the form of a multi-disciplinary team.

Many other professionals from a variety of disciplines such as chemistry, toxicology, engineering, radiation health, epidemiology, environmental health, applied sociology and health education may also be involved, to some extent, in occupational health practice. Furthermore, officials of the competent authorities, employers, workers and their representatives and first aid workers have an essential role and even a direct responsibility in the implementation of occupational health policies and programmes, although they are not occupational health specialists by profession. Finally, many other professions such as lawyers, architects, manufacturers, designers, work analysts, work organisation specialists, teachers in technical schools, universities and other institutions as well as the media personnel have an important role to play in the improvement of the working environment and of working conditions.

The aim of occupational health practice is to protect workers’ health and to promote the establishment and maintenance of a safe and healthy working environment as well as to promote the adaptation of work to the capabilities of workers, taking into account their state of health. A clear priority should be given to vulnerable groups and to underserved working populations. Occupational health is essentially preventive and should help the workers, individually and collectively, in safeguarding their health in their employment. It should thereby help the enterprise in ensuring healthy and safe working conditions and environment, which are criteria of efficient management and are to be found in well-run enterprises.

The field of occupational health is comprehensive and covers the prevention of all impairments arising out of employment, work injuries and work-related diseases, including occupational diseases as well as all aspects relating to the interactions between work and health. Occupational health professionals should be involved, whenever possible, in the design of health and safety equipment, methods and procedures and they should encourage workers’ participation in this field. Occupational health professionals have a role to play in the promotion of workers’ health and should assist workers in obtaining and maintaining employment notwithstanding their health deficiencies or their handicap. The word “workers” is used here in a broad sense and covers all employees, including management staff and the self-employed.

The approach in occupational health is multi-disciplinary and inter-sectoral. There is a wide range of obligations and complex relationships among those concerned. It is therefore important to define the role of occupational health professionals and their relationships with other professionals, with other health professionals and with social partners in the purview of economic, social and health policies and development. This calls for a clear view about the ethics of occupational health professionals and standards in their professional conduct.

In general, duties and obligations are defined by statutory regulations. Each employer has the responsibility for the health and safety of the workers in his or her employment. Each profession has its responsibilities which are related to the nature of its duties. When specialists of several professions are working together within a multi-disciplinary approach, it is important that they base their action on some common principles of ethics and that they have an understanding of each others’ obligations, responsibilities and professional standards. Special care should be taken with respect to ethical aspects, in particular when there are conflicting rights such as the right to the protection of employment and the right to the protection of health, the right to information and the right to confidentiality, as well as individual rights and collective rights.

Some of the conditions of execution of the functions of occupational health professionals and the conditions of operation of occupational health services are often defined in statutory regulations. One of the basic requirements for a sound occupational health practice is a full professional independence, i.e. that occupational health professionals must enjoy an independence in the exercise of their functions which should enable them to make judgements and give advice for the protection of the workers’ health and for their safety within the undertaking in accordance with their knowledge and conscience.

There are basic requirements for acceptable occupational health practice; these conditions of operation are sometimes specified by national regulations and include in particular free access to the work place, the possibility of taking samples and assessing the working environment, making job analyses and participating in enquiries after an accident as well as the possibility to consult the competent authority on the implementation of occupational safety and health standards in the undertaking. Occupational health professionals should be allocated a budget enabling them to carry out their functions according to good practice and to the highest professional standards. This should include adequate staffing, training and re-training, support and access to relevant information and to an appropriate level of senior management.

This code lays down general principles of ethics in occupational health practice. More detailed guidance on a number of particular aspects can be found in national codes of ethics or guidelines for specific professions. Reference to a number of documents on ethics in occupational health are given at the end of this document. The provisions of this code aim to serve as a guide for all those who carry out occupational health activities and cooperate in the improvement of the working environment and working conditions. Its purpose is to contribute, as regards ethics and professional conduct, to the development of common rules for team work and a multi-disciplinary approach in occupational health.

The preparation of this code of ethics was discussed by the Board of ICOH in Sydney in 1987. A draft was distributed to the Board members in Montreal and was subject to a process of consultations at the end of 1990 and at the beginning of 1991. The ICOH Code of Ethics for Occupational Health Professionals was approved by the Board on 29 November 1991. This document will be periodically reviewed. Comments to improve its content may be addressed to the Secretary-General of the International Commission on Occupational Health.

Basic Principles

The three following paragraphs summarize the principles of ethics on which is based the International Code of Ethics for Occupational Health Professionals prepared by the International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH).

Occupational health practice must be performed according to the highest professional standards and ethical principles. Occupational health professionals must serve the health and social wellbeing of the workers, individually and collectively. They also contribute to environmental and community health.

The obligations of occupational health professionals include protecting the life and the health of the worker, respecting human dignity and promoting the highest ethical principles in occupational health policies and programmes. Integrity in professional conduct, impartiality and the protection of the confidentiality of health data and of the privacy of workers are part of these obligations.

Occupational health professionals are experts who must enjoy full professional independence in the execution of their functions. They must acquire and maintain the competence necessary for their duties and require conditions which allow them to carry out their tasks according to good practice and professional ethics.

Duties and Obligations of Occupational Health Professionals

- The primary aim of occupational health practice is to safeguard the health of workers and to promote a safe and healthy working environment. In pursuing this aim, occupational health professionals must use validated methods of risk evaluation, propose efficient preventive measures and follow-up their implementation. The occupational health professionals must provide competent advice to the employer on fulfilling his or her responsibility in the field of occupational safety and health and they must honestly advise the workers on the protection and promotion of their health in relation to work. The occupational health professionals should maintain direct contact with safety and health committees, where they exist.

- Occupational health professionals must continuously strive to be familiar with the work and the working environment as well as to improve their competence and to remain well informed in scientific and technical knowledge, occupational hazards and the most efficient means to eliminate or to reduce the relevant risks. Occupational health professionals must regularly and routinely, whenever possible, visit the workplaces and consult the workers, the technicians and the management on the work that is performed.

- The occupational health professionals must advise the management and the workers on factors within the undertaking which may affect workers’ health. The risk assessment of occupational hazards must lead to the establishment of an occupational safety and health policy and of a programme of prevention adapted to the needs of the undertaking. The occupational health professionals must propose such a policy on the basis of scientific and technical knowledge currently available as well as of their knowledge of the working environment. Occupational health professionals must also provide advice on a programme of prevention which should be adapted to the risks in the undertaking and which should include, as appropriate, measures for controlling occupational safety and health hazards, for monitoring them and for mitigating their consequences in the case of an accident.

- Special consideration should be given to the rapid application of simple preventive measures which are cost-effective, technically sound and easily implemented. Further investigations must check whether these measures are efficient and a more complete solution must be recommended, where necessary. When doubts exist about the severity of an occupational hazard, prudent precautionary action should be taken immediately.

- In the case of refusal or of unwillingness to take adequate steps to remove an undue risk or to remedy a situation which presents evidence of danger to health or safety, the occupational health professionals must make, as rapidly as possible, their concern clear, in writing, to the appropriate senior management executive, stressing the need for taking into account scientific knowledge and for applying relevant health protection standards, including exposure limits, and recalling the obligation of the employer to apply laws and regulations and to protect the health of workers in his or her employment. Whenever necessary, the workers concerned and their representatives in the enterprise should be informed and the competent authority should be contacted.

- Occupational health professionals must contribute to the information of workers on occupational hazards to which they may be exposed in an objective and prudent manner which does not conceal any fact and emphasises the preventive measures. The occupational health personnel must cooperate with the employer and assist him or her in fulfilling his or her responsibility of providing adequate information and training on health and safety to the management personnel and workers, about the known level of certainty concerning the suspected occupational hazards.

- Occupational health professionals must not reveal industrial or commercial secrets of which they may become aware in the exercise of their activities. However, they cannot conceal information which is necessary to protect the safety and health of workers or of the community. When necessary, the occupational health professionals must consult the competent authority in charge of supervising the implementation of the relevant legislation.

- The objectives and the details of the health surveillance must be clearly defined and the workers must be informed about them. The validity of such surveillance must be assessed and it must be carried out with the informed consent of the workers by an occupational health professional approved by the competent authority. The potentially positive and negative consequences of participation in screening and health surveillance programmes should be discussed with the workers concerned.

- The results of examinations, carried out within the framework of health surveillance must be explained to the worker concerned. The determination of fitness for a given job should be based on the assessment of the health of the worker and on a good knowledge of the job demands and of the worksite. The workers must be informed of the opportunity to challenge the conclusions concerning their fitness for their work that they feel contrary to their interest. A procedure of appeal must be established in this respect.

- The results of the examinations prescribed by national laws or regulations must only be conveyed to management in terms of fitness for the envisaged work or of limitations necessary from a medical point of view in the assignment of tasks or in the exposure to occupational hazards. General information on work fitness or in relation to health or the potential or probable health effects of work hazards, may be provided with the informed consent of the worker concerned.

- Where the health condition of the worker and the nature of the tasks performed are such as to be likely to endanger the safety of others, the worker must be clearly informed of the situation. In the case of a particularly hazardous situation, the management and, if so required by national regulations, the competent authority must also be informed of the measures necessary to safeguard other persons.

- Biological tests and other investigations must be chosen from the point of view of their validity for protection of the health of the worker concerned, with due regard to their sensitivity, their specificity and their predictive value. Occupational health professionals must not use screening tests or investigations which are not reliable or which do not have a sufficient predictive value in relation to the requirements of the work assignment. Where a choice is possible and appropriate, preference must always be given to non-invasive methods and to examinations, which do not involve any danger to the health of the worker concerned. An invasive investigation or an examination which involves a risk to the health of the worker concerned may only be advised after an evaluation of the benefits and the risks involved and cannot be justified in relation to insurance claims. Such an investigation is subject to the worker’s informed consent and must be performed according to the highest professional standards.

- Occupational health professionals may contribute to public health in different ways, in particular by their activities in health education, health promotion and health screening. When engaging in these programmes, occupational health professionals must seek the participation of both employers and workers in their design and in their implementation. They must also protect the confidentiality of personal health data of the workers.

- Occupational health professionals must be aware of their role in relation to the protection of the community and of the environment. They must initiate and participate, as appropriate, in identifying, assessing and advising on the prevention of environmental hazards arising or which may result from operations or processes in the enterprise.

- Occupational health professionals must report objectively to the scientific community on new or suspected occupational hazards and relevant preventive methods. Occupational health professionals involved in research must design and carry out their activities on a sound scientific basis with full professional independence and follow the ethical principles attached to research work and to medical research, including an evaluation by an independent committee on ethics, as appropriate.

Conditions of Execution of the Functions of Occupational Health Professionals

- Occupational health professionals must always act, as a matter of priority, in the interest of the health and safety of the workers. Occupational health professionals must base their judgements on scientific knowledge and technical competence and call upon specialized expert advice as necessary. Occupational health professionals must refrain from any judgement, advice or activity which may endanger the trust in their integrity and impartiality.

- Occupational health professionals must maintain full professional independence and observe the rules of confidentiality in the execution of their functions. Occupational health professionals must under no circumstances allow their judgement and statements to be influenced by any conflict of interest, in particular when advising the employer, the workers or their representatives in the undertaking on occupational hazards and situations which present evidence of danger to health or safety.

- The occupational health professionals must build a relationship of trust, confidence and equity with the people to whom they provide occupational health services. All workers should be treated in an equitable manner without any form of discrimination with regards to age, sex, social status, ethnic background, political, ideological or religious opinions, nature of the illness or the reason which led to the consultation of the occupational health professionals. A clear channel of communication must be established and maintained between occupational health professionals and the senior management executive responsible for decisions at the highest level about the conditions and the organisation of work and the working environment in the undertaking, or with the board of directors.

- Whenever appropriate, occupational health professionals must request that a clause on ethics be incorporated in their contract of employment. This clause on ethics should include, in particular, the right of occupational health specialists to apply professional standards and principles of ethics. Occupational health professionals must not accept conditions of occupational health practice which do not allow for performance of their functions according to the desired professional standards and principles of ethics. Contracts of employment should contain guidance on the legal contractual and ethical position on matters of conflict, access to records and confidentiality in particular. Occupational health professionals must ensure that their contract of employment or service does not contain provisions which could limit their professional independence. In case of doubt, the terms of the contract must be checked with the assistance of the competent authority.

- Occupational health professionals must keep good records with the appropriate degree of confidentiality for the purpose of identifying occupational health problems in the enterprise. Such records include data relating to the surveillance of the working environment, personal data such as the employment history and health-related data such as the history of occupational exposure, results of personal monitoring of exposure to occupational hazards and fitness certificates. Workers must be given access to their own records.

- Individual medical data and the results of medical investigations must be recorded in confidential medical files which must be kept secured under the responsibility of the occupational health physician or the occupational health nurse. Access to medical files, their transmission, as well as their release, and the use of information contained in these files is governed by national laws or regulations and national codes of ethics for medical practitioners.

- When there is no possibility of individual identification, information on group health data of workers may be disclosed to management and workers’ representatives in the undertaking or to safety and health committees, where they exist, in order to help them in their duties to protect the health and safety of exposed groups of workers. Occupational injuries and occupational diseases must be reported to the competent authority according to national laws and regulations.

- Occupational health professionals must not seek personal information which is not relevant to the protection of workers’ health in relation to work. However, occupational physicians may seek further medical information or data from the worker’s personal physician or hospital medical staff, with the worker’s informed consent, for the purpose of protecting the health of this worker. In so doing, the occupational health physician must inform the worker’s personal physician or hospital medical staff of his or her role and of the purpose for which the medical information or data is required. With the agreement of the worker, the occupational physician or the occupational health nurse may, if necessary, inform the worker’s personal physician of relevant health data as well as of hazards, occupational exposures and constraints at work which represent a particular risk in view of the worker’s state of health.

- Occupational health professionals must cooperate with other health professionals in the protection of the confidentiality of the health and medical data concerning workers. When there are problems of particular importance, occupational health professionals must inform the competent authority of procedures or practices currently used which are, in their opinion, contrary to the principles of ethics. This concerns in particular the medical confidentiality, including verbal comments, record keeping and the protection of confidentiality in the recording and in the use of information placed on computer.

- Occupational health professionals must increase the awareness of employers, workers and their representatives of the need for full professional independence and avoid any interference with medical confidentiality in order to respect human dignity and to enhance the acceptability and effectiveness of occupational health practice.

- Occupational health professionals must seek the support of employers, workers and their organisations, as well as of the competent authorities, for implementing the highest standards of ethics in occupational health practice. They should institute a programme of professional audit of their own activities in order to ensure that appropriate standards have been set, that they are being met and that deficiencies, if any, are detected and corrected.

(This article is a reprint of the ICOH published Code.)

Case Study: Drugs and Alcohol in the Workplace - Ethical Considerations

Introduction

The management of alcohol and drug problems in the workplace can pose ethical dilemmas for an employer. What course of conduct an employer takes involves a balancing of considerations with respect to individuals who have alcohol and drug abuse problems with the obligation to correctly manage the shareholder’s financial resources and safeguard the safety of other workers.

Although in a number of cases both preventive and remedial measures can be of mutual interest to the workers and the employer, in other situations what may be advanced by the employer as good for the worker’s health and well-being may be viewed by workers as a significant restriction on individual freedom. Also, employer actions taken because of concerns about safety and productivity may be viewed as unnecessary, ineffective and an unwarranted invasion of privacy.

Right to Privacy at Work

Workers consider privacy to be a fundamental right. It is a legal right in some countries, but one which, however, is interpreted flexibly according to the needs of the employer to ensure, inter alia, a safe, healthy and productive workforce, and to ensure that a company’s products or services are not dangerous to consumers and the public at large.

The use of alcohol or drugs is normally done in a worker’s free time and off-premises. In the case of alcohol, it can also occur on-premises if this is allowed by local law. Any intrusion by the employer with respect to the worker’s use of alcohol or drugs should be justified by a compelling reason, and should take place by the least intrusive method if costs are roughly comparable.

Two types of employer practices designed to identify alcohol and drug users among job applicants and workers have aroused strong controversy: testing of bodily substances (breath, blood, urine) for alcohol or drugs, and oral or written inquiries into present and past alcohol or drug use. Other methods of identification such as observation and monitoring, and computer-based performance testing, have also raised issues of concern.

Testing of Bodily Substances

The testing of bodily substances is perhaps the most controversial of all methods of identification. For alcohol, this normally involves using a breathalyser device or taking a blood sample. For drugs, the most widespread practice is urinalysis.

Employers argue that testing is useful to promote safety and prevent liability for accidents; to determine medical fitness for work; to enhance productivity; to reduce absenteeism and tardiness; to control health costs; to promote confidence among the public that a company’s products or services are being produced or delivered safely and properly, to prevent embarrassment to the employer’s image, to identify and rehabilitate workers, to prevent theft and to discourage illegal or socially unbecoming conduct by workers.

Workers argue that testing is objectionable because taking samples of bodily substances is very invasive of privacy; that the procedures of taking samples of bodily substances can be humiliating and degrading, particularly if one must produce a urine sample under the watchful eye of a controller to prevent cheating; that such testing is an inefficient way to promote safety or health; and that better prevention efforts, more attentive supervision and the introduction of employee assistance programmes are more efficient ways to promote safety and health.

Other arguments against screening include that testing for drugs (as opposed to alcohol) does not give an indication of current impairment, but only prior use, and therefore is not indicative of an individual’s present ability to perform the job; that testing, particularly drug testing, requires sophisticated procedures; that in case such procedures are not observed, misidentification having dramatic and unfair job consequences may occur; and that such testing can create morale problems between management and labour and an atmosphere of distrust.

Others argue that testing is designed to identify behaviour that is morally unacceptable to the employer, and that there is no persuasive empirical basis that many workplaces have alcohol or drug problems that require pre-employment, random or periodic screening, which constitute severe intrusions into a worker’s privacy because these forms of testing are done in the absence of reasonable suspicion. It has also been asserted that testing for illegal drugs is tantamount to the employer assuming a law enforcement role which is not the vocation or role of an employer.

Some European countries, including Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, allow alcohol and drug testing, although usually in narrowly defined circumstances. For example, in many European countries statutes exist which allow the police to test workers engaged in road, aviation, rail and sea transport, normally based on reasonable suspicion of intoxication on the job. In the private sector, testing has also been reported to occur, but it is usually on the basis of reasonable suspicion of intoxication on the job, in post-accident or post-incident circumstances. Some pre-employment testing and, in very limited cases, periodic or random testing, has been reported in the context of safety-sensitive positions. However, random testing is relatively rare in European countries.

In the United States, different standards apply depending on whether alcohol and drug testing is carried out by the public- or private-sector establishments. Testing conducted by the government or by companies pursuant to legal regulation must satisfy constitutional requirements against unreasonable state action. This has led the courts to allow testing only for safety- and security-sensitive jobs, but to allow virtually all types of testing including pre-employment, reasonable cause, periodic, post-incident or post-accident, and random testing. There is no requirement that the employer demonstrate a reasonable suspicion of drug abuse in a given enterprise or administrative unit, or on the basis of individual use, before engaging in testing. This has led some observers to claim such an approach is unethical because there is no requirement for the demonstration of even a reasonable suspicion of a problem at the enterprise or individual level before any type of testing, including random screening, occurs.

In the private sector, there are no federal constitutional restrictions on testing, although a small number of American states have some procedural and substantive legal restrictions on drug testing. In most American states, however, there are few if any legal restrictions on alcohol and drug testing by private employers and it is performed on an unprecedented scale compared to European private employers, who test principally for reasons of safety.

Inquiries or Questionnaires

Although less intrusive than testing of bodily substances, employer inquiries or questionnaires designed to elicit prior and current use of alcohol and drugs are invasive of workers’ privacy and irrelevant to the requirements of most jobs. Australia, Canada, a number of European countries, and the United States have privacy laws applicable to the public and/or private sectors which require that inquiries or questionnaires be directly relevant to the job in question. In most cases, these laws do not explicitly restrict inquiries about substance abuse, although in Denmark, for example, it is prohibited to collect and store information about excessive use of intoxicants. Similarly, in Norway and Sweden, alcohol and drug abuse are characterized as sensitive data which in principle cannot be collected unless deemed necessary for specific reasons and approved by the data inspectorate authority.

In Germany, the employer can ask questions only to judge the abilities and competence of the candidate with regard to the job in question. A job applicant may answer untruthfully to inquiries of a personal character that are irrelevant. For example, it has been held by court decision that a woman can legally answer that she is not pregnant when in fact she is. Such privacy issues are judicially decided on a case-by-case basis, and whether one could answer untruthfully about one’s present or prior alcohol or drug consumption would probably depend on whether such inquiries were reasonably relevant to performance of the job in question.

Observation and Monitoring

Observation and monitoring are the traditional methods of detection of alcohol and drug problems in the workplace. Simply put, if a worker shows clear signs of intoxication or its after-effects, then he or she can be identified on the basis of such behaviour by the person’s supervisor. This reliance on management supervision to detect alcohol and drug problems is the most widespread, the least controversial and the most favoured by workers’ representatives. The doctrine that holds that treatment of alcohol and drug problems has a higher chance of success if it is based on early intervention, however, raises an ethical issue. In applying such an approach to observation and monitoring, supervisors might be tempted to note signs of ambiguous behaviour or decreased work performance, and speculate about a worker’s private alcohol or drug use. Such minute observation combined with a certain degree of speculation could be characterized as unethical, and supervisors should confine themselves to instances where a worker is clearly under the influence, and hence cannot function in the job at an acceptable level of performance.

The other question that arises is what a supervisor should do when a worker shows clear signs of intoxication. A number of commentators previously felt that the worker should be confronted by the supervisor, who should play a direct role in assisting the worker. However, most observers currently are of the view that such confrontation can be counterproductive and possibly aggravate a worker’s alcohol or drug problems, and that the worker should be referred to an appropriate health service for assessment and, if required, counselling, treatment and rehabilitation.

Computer-Based Performance Tests

Some commentators have suggested computer-based performance tests as an alternative method of detecting workers under the influence of alcohol or drugs at work. It has been argued that such tests are superior to other identification alternatives because they measure current impairment rather than previous use, they are more dignified and less intrusive of personal privacy, and persons can be identified as impaired for any reason, for example, lack of sleep, illness, or alcohol or drug intoxication. The main objection is that technically these tests may not accurately measure the job skills that they purport to measure, that they may not detect low amounts of alcohol and drugs which could potentially affect performance, and that the most sensitive and accurate tests are also those which are the most costly and difficult to set up and administer.

Ethical Issues in Choosing between Discipline and Treatment

One of the most difficult issues for an employer is when discipline should be imposed as a response to an incident of alcohol or drug use at work; when counselling, treatment and rehabilitation should be the appropriate response; and under what circumstances both alternatives—discipline and treatment—should be undertaken concurrently. Bound up in this is the question as to whether alcohol and drug use is essentially behavioural in nature, or an illness. The view that is advanced here is that alcohol and drug use is essentially behavioural in nature, but that consumption of inappropriate quantities over a period of time can lead to a condition of dependence which can be characterized as an illness.

From the employer’s point of view, it is conduct—the worker’s job performance—that is of primary interest. An employer has the right and, in certain circumstances where the worker’s misconduct has implications for the safety, health or economic well-being of others, the duty to impose disciplinary sanctions. Being under the influence of alcohol or drugs at work can be correctly characterized as misconduct, and such a situation can be characterized as serious misconduct if the person occupies a safety-sensitive position. However, a person experiencing problems at work connected to alcohol or drugs may also have a health problem.

For ordinary misconduct involving alcohol or drugs, an employer should offer the worker assistance to determine if the person has a health problem. The decision to refuse an offer of assistance may be a legitimate choice for workers who may choose not to expose their health problems to the employer, or who may not have a health problem at all. Depending on the circumstances, the employer may wish to impose a disciplinary sanction as well.

The response of an employer to a situation involving serious misconduct connected with alcohol or drugs, such as being under the influence of alcohol or drugs in a safety-sensitive position, should probably be different. Here the employer is confronted with both the ethical duty to maintain safety for other workers and the public at large, and the ethical obligation to be fair to the worker concerned. In such a situation, the employer’s principal ethical concern should be to safeguard public safety and immediately remove the worker from the job. Even in the case of such serious misconduct, the employer should assist the worker to obtain health care as appropriate.

Ethical Issues in Counselling, Treatment and Rehabilitation

Ethical issues can also arise with regard to assistance extended to workers. The initial problem that can arise is one of assessment and referral. Such services may be undertaken by the occupational health service in an establishment, by a health care provider associated with an employee assistance programme, or by the worker’s personal physician. If none of the above possibilities exists, an employer may need to identify professionals who specialize in alcohol and drug counselling, treatment and rehabilitation, and suggest that the worker contact one of them for assessment and referral, if necessary.

An employer should also make attempts to reasonably accommodate a worker during absence for treatment. Paid sick leave and other types of appropriate leave should be put at the disposition of the worker to the extent possible for in-patient treatment. If out-patient treatment requires adjustments to the person’s work schedule or transfer to part-time status, then an employer should make reasonable accommodation to such requests, particularly as the individual’s continued presence in the workforce may be a stabilizing factor in recovery. The employer should also be supportive and monitor the worker’s performance. To the extent that the working environment may have contributed initially to the alcohol or drug problem, the employer should make appropriate changes in the working environment. If this is not possible or practical, the employer should consider transferring the worker to another position with reasonable retraining if necessary.

One difficult ethical question which arises is to what extent an employer should continue to support a worker who is absent from work for health reasons due to alcohol and drug problems, and at what stage an employer should dismiss such a worker for reasons of illness. As a guiding principle, an employer should treat absence from work associated with alcohol and drug problems as any absence from work for health reasons, and the same considerations that apply to any dismissal for reasons of health should also be applicable to dismissal for absence due to alcohol and drug problems. Moreover, employers should keep in mind that relapse can occur and is, in fact, part of a process towards complete recovery.

Ethical Issues in Dealing with Illegal Drug Users

An employer is faced with difficult ethical choices when dealing with a worker who uses, or who in the past has used, illegal drugs. The question, for example, has been raised as to whether an employer should dismiss a worker who is arrested or convicted for illegal drug offences. If the offence is of such a serious nature that the person must serve time in prison, evidently the person will not be available for work. However, in many cases consumers or small-time pushers who sell just enough to support their own habit may be given only suspended sentences or fines. In such a case, an employer should ordinarily not consider disciplinary sanctions or dismissal for such off-duty and off-premises conduct. In some countries, if the person has a spent conviction, i.e., a fine that has been paid or a suspended or actual prison sentence that has been completed in full, there may be an actual legal bar against employment discrimination towards the person in question.

Another question that is sometimes posed is whether a previous or current user of illegal drugs should be subject to job discrimination by employers. It is argued here that the ethical response should be that no discrimination should take place against either previous or current users of illegal drugs if it occurs during off-duty time and off the establishment’s premises, as long as the person is otherwise fit to perform the job. In this respect, the employer should be prepared to make a reasonable accommodation in the arrangement of work to a current user of illegal drugs who is absent for purposes of counselling, treatment and rehabilitation. Such a view is recognized in Canadian federal human rights law, which prohibits job discrimination on the basis of disability and qualifies alcohol and drug dependence as a disability. Similarly, French labour law prohibits job discrimination on the basis of health or handicap unless the occupational physician determines the person is unfit for work. American federal law, on the other hand, protects previous illegal drug users from discrimination, but not current users.