Sex Industry

The sex industry is a major industry both in developing countries, where it is a major source of foreign currency, and in industrialized countries. The two main divisions of the sex industry are (1) prostitution, which involves the direct exchange of a sexual service for money or other means of economic compensation and (2) pornography, which involves the performance of sex-related tasks, sometimes involving two or more people, for still photographs, in motion pictures and videotapes, or in a theatre or nightclub, but does not include direct sexual activity with the paying client. The line between prostitution and pornography is not very clear, however, as some prostitutes restrict their work to erotic acting and dance for private clients, and some workers in the pornography industry go beyond display to engaging in direct sexual contact with members of the audience, for example, in strip- and lap-dancing clubs.

The legal status of prostitution and pornography varies from one country to another, ranging from complete prohibition of the sex-money exchange and the businesses in which it takes place, as in the United States; to decriminalization of the exchange itself but prohibition of the businesses, as in many European countries; to toleration of both independent and organized prostitution, for example, in the Netherlands; to regulation of the prostitute under public health law, but prohibition for those who fail to comply, as in a number of Latin American and Asian countries. Even where the industry is legal, governments have remained ambivalent and few, if any, have attempted to use occupational safety and health regulations to protect the health of sex workers. However, since the early 1970s, both prostitutes and erotic performers have been organizing in many countries (Delacoste and Alexander 1987; Pheterson 1989), and have increasingly addressed the issue of occupational safety as they attempt to reform the legal context of their work.

A particularly controversial aspect of sex work is the involvement of young adolescents in the industry. There is not enough space to discuss this at any length here, but it is important that solutions to the problems of adolescent prostitution be developed in the context of responses to child labour and poverty, in general, and not as an isolated phenomenon. A second controversy has to do with the extent to which adult sex work is coerced or the result of individual decision. For the vast majority of sex workers, it is a temporary occupation, and the average worklife, worldwide, is from 4 to 6 years, including some who work only for a few days or intermittently (e.g., between other jobs), and others who work for 35 years or more. The primary factor in the decision to do sex work is economics, and in all countries, work in the sex industry pays much better than other work for which extensive training is not required. Indeed, in some countries, the higher-paid prostitutes earn more than some physicians and attorneys. It is the conclusion of the sex workers’ rights movement that it is difficult to establish issues like consent and coercion when the work itself is illegal and heavily stigmatized. The important thing is to support sex workers’ ability to organize on their own behalf, for example, in trade unions, professional associations, self-help projects and political advocacy organizations.

Hazards and Precautions

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The most obvious occupational hazard for sex workers, and the one which has received the most attention historically, is STDs, including syphilis and gonorrhoea, chlamydia, genital ulcer disease, trichomonas and herpes, and, more recently, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS.

In all countries, the risk of infection with HIV and other STDs is greatest among the lowest-income sex workers, whether on the street in the industrial countries, in low-income brothels in Asia and Latin America or in residential compounds in impoverished communities in Africa.

In industrialized countries, studies have found HIV infection among female prostitutes to be associated with injecting drug use by either the prostitute or her ongoing personal partner, or with the prostitute’s use of “crack”, a smokeable form of cocaine—not with the number of clients or with prostitution per se. There have been few if any studies of pornography workers, but it is likely to be similar. In developing countries, the primary factors are less clear, but may include a higher prevalence of untreated conventional STDs, which some researchers think facilitate transmission of HIV, and a reliance on informal street vendors or poorly equipped clinics for treatment of STDs, if treatment involves injections with unsterile needles. Injection of recreational drugs is also associated with HIV infection in some developing countries (Estébanez, Fitch and Nájera 1993). Among male prostitutes, HIV infection is more often associated with homosexual activity, but is also associated with injecting drug use and sex in the context of drug dealing.

Precautions involve the consistent use of latex or polyurethane condoms for fellatio and vaginal or anal intercourse, where possible with lubricants (water-based for latex condoms, water or oil-based for polyurethane condoms), latex or polyurethane barriers for cunnilingus and oral-anal contact and gloves for hand-genital contact. While condom use has been increasing among prostitutes in most countries, it is still the exception in the pornography industry. Women performers sometimes use spermicides to protect themselves. However, while the spermicide nonoxynol-9 has been shown to kill HIV in the laboratory, and reduces the incidence of conventional STD in some populations, its efficacy for HIV prevention in actual use is far less clear. Moreover, the use of nonoxynol-9 more than once a day has been associated with significant rates of vaginal epithelial disruption (which could increase the female sex worker’s vulnerability to HIV infection) and sometimes an increase in vaginal yeast infections. No one has studied its use for anal sex.

Access to sex worker–sensitive health care is also important, including care for other health problems, not just STDs. Traditional public health approaches that involve mandatory licensing or registration, and regular health examinations, have not been effective in reducing the risk of infection for the workers, and are contrary to World Health Organization policies that oppose mandatory testing.

Injuries. Although there have not been any formal studies of other occupational hazards, anecdotal evidence suggests that repetitive stress injuries involving the wrist and shoulder are common among prostitutes who do “hand jobs”, and jaw pain is sometimes associated with performing fellatio. In addition, street prostitutes and erotic dancers may develop foot, knee and back problems related to working in high heels. Some prostitutes have reported chronic bladder and kidney infections, due to working with a full bladder or not knowing how to position oneself to prevent deep penetration during vaginal intercourse. Finally, some groups of prostitutes are very vulnerable to violence, especially in countries where the laws against prostitution are heavily enforced. The violence includes rape and other sexual assault, physical assault and murder, and is committed by police, clients, sex work business managers and domestic partners. The risk of injury is greatest among younger, less experienced prostitutes, especially those who begin working during adolescence.

Precautions include ensuring that sex workers are trained in the least stressful way to perform different sexual acts to prevent repetitive stress injuries and bladder infections, and self-defence training to reduce vulnerability to violence. This is particularly important for young sex workers. In the case of violence, another important remedy is to increase the willingness of police and prosecuting attorneys to enforce the laws against rape and other violence when the victims are sex workers.

Alcohol and drug use. When prostitutes work in bars and nightclubs, they are often required by management to encourage clients to drink, as well as to drink with clients, which can be a serious hazard for individuals who are vulnerable to alcohol addiction. In addition, some begin to use drugs (e.g., heroin, amphetamines and cocaine) to help deal with the stress of their work, while others used drugs prior to beginning sex work, and turned to sex work in order to pay for their drugs. With injecting drug use, vulnerability to HIV infection, hepatitis and a range of bacterial infections increases if drug users share needles.

Precautions include workplace regulations to ensure that prostitutes can drink non-alcoholic beverages when with clients, the provision of sterile injection equipment and, where possible, legal drugs to sex workers who inject drugs, and increasing access to drug and alcohol addiction treatment programmes.

Professional Sports

Sports activities involve a great number of injuries. Precautions, conditioning and safety equipment, when used properly, will minimize sports injuries.

In all sports, conditioning year round is encouraged. Bone, ligaments and muscles respond in a physiological fashion by gaining both size and strength (Clare 1990). This increases the athlete’s agility to avoid any injurious physical contact. All sports requiring weightlifting and strengthening should be under the supervision of a strength coach.

Contact Sports

Contact sports such as American football and hockey are particularly dangerous. The aggressive nature of football requires the player to strike or tackle the opposing player. The focus of the game is to possess the ball with the intent of physically striking anyone in one’s path. The equipment should be well-fitting and offer adequate protection. (figure 1). The helmet with appropriate face mask is standard and is critical in this sport (figure 2). It should not slide or twist and the straps should be applied snugly (American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons 1991).

Figure 1. Snug fitting football pads.

MISSING

Source: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons 1991

Figure 2. American football helmet.

MISSING

Source: Clare 1990

Unfortunately, the helmet is sometimes used in an unsafe manner whereby the player “spears” an opponent. This can lead to cervical spine injuries and possible paralysis. It can also lead to careless play in sports like hockey, when players feel they can be more free with the use of their stick and risk slashing the face and body of the opponent.

Knee injuries are quite common in football and basketball. In minor injuries, an elastic “sleeve” (figure 3) which provides compressive support may be useful. The ligaments and cartilage of the knee are prone to stress as well as impact trauma. The classic combination of cartilage and ligamentous insult was first described by O’Donoghue (1950). An audible “pop” may be heard and felt, followed by swelling, if there are ligament injuries. Surgical intervention may be needed before the player may resume activities. A derotational brace may be worn post-operatively and by players with partial tear of the anterior cruciate ligament but with enough intact fibres able to sustain their activities. These braces must be well padded to protect the injured extremity and other players (Sachare 1994a).

Figure 3. Patella cut-out sleeve.

Huie, Bruno and Norman Scott

In hockey, the velocity of both the players and the hard hockey puck warrants the use of protective padding and helmet (figure 4). The helmet should have a face shield to prevent facial and dental injuries. Even with helmets and protective padding to vital areas, severe injuries such as fractures of extremities and spine do occur in football and hockey.

Figure 4. Padded hockey gloves.

Huie, Bruno and Norman Scott

In both American football and hockey, a complete medical kit (which includes diagnostic instruments, resuscitation equipment, immobilization devices, medication, wound care supplies, spine board and stretcher) and emergency personnel should be available (Huie and Hershman 1994). If possible, all contact sports should have this available. Radiographs should be obtained of all injuries to rule out any fractures. Magnetic resonance imaging has been found to be very helpful in determining soft tissue injuries.

Basketball

Basketball is also a contact sport, but protective equipment is not worn. The focus of the player is to have possession of the ball and their intent is not to strike the opposing players. Injuries are minimized due to the player’s conditioning and speed in averting any hard contact.

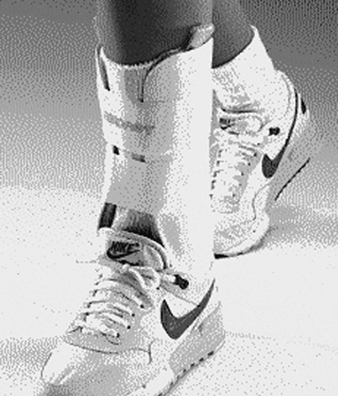

The most common injury to the basketball player are ankle sprains. Evidence of ankle sprains has been noted in about 45% of players (Garrick 1977; Huie and Scott 1995). The ligaments involved are the deltoid ligament medially and the anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular, and calcaneofibular ligaments laterally. X rays should be obtained to rule out any fractures which may occur. These radiographs should include the entire lower leg to rule out a Maisonneuve fracture (VanderGriend, Savoie and Hughes 1991). In the chronically sprained ankle, use of a semi-rigid ankle stirrup will minimize further insult to the ligaments (figure 5).

Figure 5. Rigid ankle stirrup.

AirCast

Finger injuries may result in ruptures of the supporting ligamentous structures. This can result in a Mallet finger, Swann Neck deformity and Boutonierre deformity (Bruno, Scott and Huie 1995). These injuries are quite common and are due to direct trauma with the ball, other players and the backboard or rim. Prophylactic taping of ankles and fingers helps minimize any accidental twisting and hyperextension of the joints.

Facial injuries (lacerations) and fractures of the nose due to contact with opponents’ flailing arms or bony prominences, and contact with the floor or other stationary structures have been encountered. A clear light-weight protective mask may help in minimizing this type of injury.

Baseball

Baseballs are extremely hard projectiles. The player must always be cognizant of the ball not only for safety reasons but for the strategy of the game itself. Batting helmets for the offensive player, and chest protector and catcher’s mask/helmet (figure 6). for the defensive player are required protective equipment. The ball is hurled at times in excess of 95 mph, sometimes resulting in bone fractures. Any head injuries should have a full neurological work-up, and, if loss of consciousness is present, radiographs of the head should be taken.

Figure 6. Protective cather's mask.

MISSING

Huie, Bruno and Norman Scott

Soccer

Soccer can be a contact sport resulting in trauma to the lower extremity. Ankle injuries are very common. The protection that would minimize this would be taping and the use of a semi-rigid ankle stirrup. It has been found that the effectiveness of the taped ankle diminishes after about 30 minutes of vigorous activities. Tears of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee are often encountered and most likely will require a reconstructive procedure if the player wishes to continue participating in this sport. Anterior medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) is extremely common. The hypothesis is that there may be an inflammation to the periosteal sleeve around the tibia. In extreme situations, a stress fracture may occur. The treatment requires rest for 3 to 6 weeks and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), but high-level and professional-level players tend to compromise the treatment once the symptoms diminish as early as 1 week and thus go back to the impact activity. Hamstring pulls and groin pulls are common in the athletes who do not permit enough time to warm and stretch the musculature of the legs. Direct trauma to the lower extremities, particularly the tibia, may be minimized with the use of anterior shin guards.

Skiing

Skiing as a sport does not require any protective equipment, although goggles are encouraged to prevent eye injuries and to filter out the sun’s glare off the snow. Ski boots offer a rigid support for the ankles and have a “quick-release” mechanism in the event of a fall. These mechanisms, although helpful, are susceptible to circumstances of the fall. During the winter season, many injuries to the knee resulting in ligament and cartilage damage are encountered. This is found in the novice as well as the seasoned skier. In professional downhill skiing, helmets are required to protect the head due to the velocity of the athlete and the difficulty of stopping in the event the trajectory and direction are miscalculated.

Martial Arts and Boxing

Martial arts and boxing are hard contact sports, with little or no protective equipment. The gloves used on the professional boxing level are, however, weighted, which increases their effectiveness. Head guards at the amateur level help soften the impact of the blow. As with skiing, conditioning is extremely important. Agility, speed and strength minimize the combatant’s injuries. The blocking forces are deflected more than absorbed. Fractures and soft tissue insults are very common in this sport. Similar to volleyball, the repetitive trauma to the fingers and carpal bones of the hand results in fractures, subluxation, dislocation and ligamentous disruptions. Taping and padding of the hand and wrist may provide some support and protection, but this is minimal. Studies have shown that long-term brain damage is a serious concern for boxers (Council on Scientific Affairs of the American Medical Association 1983). Half of a group of professional boxers with more than 200 fights each had neurological signs consistent with traumatic encephalopathy.

Horse Racing

Horse racing at the professional and amateur levels requires a riding helmet. These helmets offer some protection for head injuries from falls, but they offer no attachment for the neck or spine. Experience and common sense help minimize falls, but even seasoned riders can sustain serious injuries and possibly paralysis if they land on their head. Many jockeys today also wear protective vests since being trampled under horses’ hooves is a major risk in falls and has resulted in fatalities. In harness racing, where horses pull two-wheeled carts called sulkies, collisions between sulkies has resulted in multiple pile-ups and serious injuries. For hazards to stable hands and others involved in handling the horses, see the chapter Livestock rearing.

First Aid

As a general rule, immediate icing (figure 7), compression, elevation and NSAIDs following most injuries will suffice. Pressure dressings should be applied to any open wounds, followed by an evaluation and suturing. The player should be removed from the game immediately to prevent any blood-borne contamination to other players (Sachare 1994b). Any head trauma with loss of consciousness should have a mental status and neurological work-up.

Figure 7. Cold compressive therapy.

MISSING

AirCast

Physical Fitness

Professional athletes with asymptomatic or symptomatic cardiac conditions may be hesitant in disclosing their pathology. In recent years, several professional athletes have been found to have cardiac problems that resulted in their deaths. The economic incentives of playing professional-level sports may inhibit athletes from disclosing their conditions for fear of disqualifying themselves from strenuous activities. Carefully obtained past medical and family histories followed by EKG and treadmill stress tests prove to be valuable in detecting those who are at risk. If a player is identified as a risk and still wishes to continue competing regardless of the medical-legal issues, emergency resuscitative equipment and trained personnel must be present at all practices and games.

Referees are present not only to keep the flow of the game going but to protect the players from hurting themselves and others. Referees, for the most part, are objective and have the authority to suspend any activity should an emergency condition arise. As with all competitive sports, emotion and adrenaline are flowing high; the referees are present to help the players harness these energies in a positive fashion.

Proper conditioning, warm-up and stretching prior to engaging in any competitive activity is vital to the prevention of strains and sprains. This procedure enables the muscles to perform at peak efficiency and minimizes the possibilities of strains and sprains (micro-tears). Warm-ups may very well be a simple jog or callisthenics for about 3 to 5 minutes followed by gentle stretching out of the extremities for an additional 5 to 10 minutes. With the muscle at its peak efficiency, the athlete may be able to quickly manoeuvre away from a threatening position.

General Profile

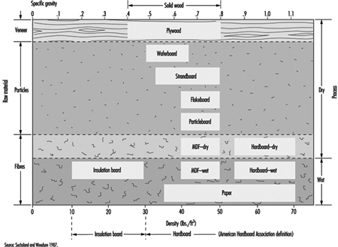

The lumber industry is a major natural resource-based industry around the world. Trees are harvested, for a variety of purposes, in the majority of countries. This chapter focuses on the processing of wood in order to produce solid wood boards and manufactured boards in sawmills and related settings. The term manufactured boards is used to refer to lumber composed of wood elements of varying sizes, from veneers down to fibres, which are held together by either additive chemical adhesives or “natural” chemical bonds. The relationship between the various types of manufactured boards is displayed in figure 1. Because of differences in process and associated hazards, manufactured boards are divided here into three categories: plywood, particleboard and fibreboard. The term particleboard is used to refer to any sheet material manufactured from small pieces of wood such as chips, flakes, splinters, strands or shreds, while the term fibreboard is used for all panels produced from wood fibres, including hardboard, medium-density fibreboard (MDF) and insulation board. The other major industrial use for wood is the manufacture of paper and related products, which is covered in the chapter Pulp and paper industry.

Figure 1. Classification of manufactured boards by particle size, density and process type.

The sawmill industry has existed in simple forms for hundreds of years, although significant advances in sawmill technology have been made this century by the introduction of electric power, improvements in saw design and, most recently, the automation of sorting and other operations. The basic techniques for making plywood have also existed for many centuries, but the term plywood did not enter into common usage until the 1920s, and its manufacture did not become commercially important until this century. The other manufactured board industries, including particleboard, waferboard, oriented strandboard, insulation board, medium-density fibreboard and hardboard, are all relatively new industries which first became commercially important after the Second World War.

Solid wood and manufactured boards may be produced from a wide variety of tree species. Species are selected on the basis of the shape and size of the tree, the physical characteristics of the wood itself, such as strength or resistance to decay, and the aesthetic qualities of the wood. Hardwood is the common name given to broad-leaved trees, which are classified botanically as angiosperms, while softwood is the common name given to conifers, which are classified botanically as gymnosperms. Many hardwoods and some softwoods which grow in tropical regions are commonly referred to as tropical or exotic woods. Although the majority of wood harvested worldwide (58% by volume) is from non-conifers, much of this is consumed as fuel, so that the majority used for industrial purposes (69%) is from conifers (FAO 1993). This may in part reflect the distribution of forests in relation to industrial development. The largest softwood forests are located in the northern regions of North America, Europe and Asia, while the major hardwood forests are located in both tropical and temperate regions.

Almost all wood destined for use in the manufacture of wood products and structures is first processed in sawmills. Thus, sawmills exist in all regions of the world where wood is used for industrial purposes. Table 1 presents 1990 statistics regarding the volume of wood harvested for fuel and industrial purposes in the major wood-producing countries on each continent, as well as volumes harvested for saw and veneer logs, a sub-category of industrial wood and the raw material for the industries described in this chapter. In developed countries the majority of wood harvested is used for industrial purposes, which includes wood used for saw and veneer logs, pulpwood, chips, particles and residues. In 1990, three countries—the United States, the former USSR and Canada - produced over half of the world’s total industrial wood as well as over half of the logs destined for saw and veneer mills. However, in many of the developing countries in Asia, Africa and South America the majority of wood harvested is used for fuel.

Table 1. Estimated wood production in 1990 (1,000 m3)

|

Wood used for |

Total wood used for |

Saw and veneer logs |

|

|

NORTH AMERICA |

137,450 |

613,790 |

408,174 |

|

United States |

82,900 |

426,900 |

249,200 |

|

Canada |

6,834 |

174,415 |

123,400 |

|

Mexico |

22,619 |

7,886 |

5,793 |

|

EUROPE |

49,393 |

345,111 |

202,617 |

|

Germany |

4,366 |

80,341 |

21,655 |

|

Sweden |

4,400 |

49,071 |

22,600 |

|

Finland |

2,984 |

40,571 |

18,679 |

|

France |

9,800 |

34,932 |

23,300 |

|

Austria |

2,770 |

14,811 |

10,751 |

|

Norway |

549 |

10,898 |

5,322 |

|

United Kingdom |

250 |

6,310 |

3,750 |

|

FORMER USSR |

81,100 |

304,300 |

137,300 |

|

ASIA |

796,258 |

251,971 |

166,508 |

|

China |

188,477 |

91,538 |

45,303 |

|

Malaysia |

6,902 |

40,388 |

39,066 |

|

Indonesia |

136,615 |

29,315 |

26,199 |

|

Japan |

103 |

29,300 |

18,377 |

|

India |

238,268 |

24,420 |

18,350 |

|

SOUTH AMERICA |

192,996 |

105,533 |

58,592 |

|

Brazil |

150,826 |

74,478 |

37,968 |

|

Chile |

6,374 |

12,060 |

7,401 |

|

Colombia |

13,507 |

2,673 |

1,960 |

|

AFRICA |

392,597 |

58,412 |

23,971 |

|

South Africa |

7,000 |

13,008 |

5,193 |

|

Nigeria |

90,882 |

7,868 |

5,589 |

|

Cameroon |

10,085 |

3,160 |

2,363 |

|

Cote d’Ivoire |

8,509 |

2,903 |

2,146 |

|

OCEANIA |

8,552 |

32,514 |

18,534 |

|

Australia |

7,153 |

17,213 |

8,516 |

|

New Zealand |

50 |

11,948 |

6,848 |

|

Papua New Guinea |

5,533 |

2,655 |

2,480 |

|

WORLD |

1,658,297 |

1,711,629 |

935,668 |

1 Includes wood used for saw and veneer logs, pulpwood, chips, particles and residues.

Source: FAO 1993.

Table 2 lists the world’s major producers of solid wood lumber, plywood, particleboard and fibreboard. The three largest producers of industrial wood overall also account for over half of world production of solid wood boards, and rank among the top five in each of the manufactured board categories. The volume of manufactured boards produced worldwide is relatively small compared to the volume of solid wood boards, but the manufactured board industries are growing at a faster rate. While the production of solid wood boards increased by 13% between 1980 and 1990, the volumes of plywood, particleboard and fibreboard increased by 21%, 25% and 19%, respectively.

Table 2. Estimated production of lumber by sector for the 10 largest world producers (1,000 m3)

|

Solid wood boards |

Plywood boards |

Particleboard |

Fibreboard |

||||

|

Country |

Volume |

Country |

Volume |

Country |

Volume |

Country |

Volume |

|

USA |

109,800 |

USA |

18,771 |

Germany |

7,109 |

USA |

6,438 |

|

Former USSR |

105,000 |

Indonesia |

7,435 |

USA |

6,877 |

Former USSR |

4,160 |

|

Canada |

54,906 |

Japan |

6,415 |

Former USSR |

6,397 |

China |

1,209 |

|

Japan |

29,781 |

Canada |

1,971 |

Canada |

3,112 |

Japan |

923 |

|

China |

23,160 |

Former USSR |

1,744 |

Italy |

3,050 |

Canada |

774 |

|

India |

17,460 |

Malaysia |

1,363 |

France |

2,464 |

Brazil |

698 |

|

Brazil |

17,179 |

Brazil |

1,300 |

Belgium-Luxembourg |

2,222 |

Poland |

501 |

|

Germany |

14,726 |

China |

1,272 |

Spain |

1,790 |

Germany |

499 |

|

Sweden |

12,018 |

Korea |

1,124 |

Austria |

1,529 |

New Zealand |

443 |

|

France |

10,960 |

Finland |

643 |

United Kingdom |

1,517 |

Spain |

430 |

|

World |

505,468 |

World |

47,814 |

World |

50,388 |

World |

20,248 |

Source: FAO 1993.

The proportion of workers in the entire workforce employed in wood products industries is generally 1% or less, even in countries with a large forest industry, such as the United States (0.6%), Canada (0.9%), Sweden (0.8%), Finland (1.2%), Malaysia (0.4%), Indonesia (1.4%) and Brazil (0.4%) (ILO 1993). While some sawmills may be located near urban areas, most tend to be located near the forests that supply their logs, and many are located in small, often isolated communities where they may be the only major source of employment and the most important component of the local economy.

Hundreds of thousands of workers are employed in the lumber industry worldwide, although exact international figures are difficult to estimate. In the United States in 1987 there were 180,000 sawmill and planer mill workers, 59,000 plywood workers and 18,000 workers employed in the production of particleboard and fibreboard (Bureau of the Census 1987). In Canada in 1991 there were 68,400 sawmill and planer mill workers and 8,500 plywood workers (Statistics Canada 1993). Even though wood production is increasing, the number of sawmill workers is decreasing due to mechanization and automation. The number of sawmill and planer mill workers in the United States was 17% higher in 1977 than in 1987, and in Canada there were 13% more in 1986 than in 1991. Similar reductions have been observed in other countries, such as Sweden, where smaller, less efficient operations are being eliminated in favour of mills with much larger capacities and modern equipment. The majority of jobs eliminated have been lower-skilled jobs, such as those involving the manual sorting or feeding of lumber.

Bullfighting and Rodeos

Bullfighting, or the corrida as it is commonly called, is popular in Spain, Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America (especially Mexico), southern France and Portugal. It is highly ritualized, with pageants, well-defined ceremonies and colourful traditional costumes. Matadors are highly respected and often begin their training at an early age in an informal apprenticeship system.

Rodeos, on the other hand, are a more recent sports event. They are an outgrowth of skills contests between cowboys illustrating their everyday activities. Today, rodeos are formalized sports events popular in the western United States, western Canada and Mexico. Professional rodeo cowboys (and some cowgirls) travel the rodeo circuit from one rodeo to another. The most common rodeo events are bronco riding, bull riding, steer wrestling (bulldogging) and calf roping.

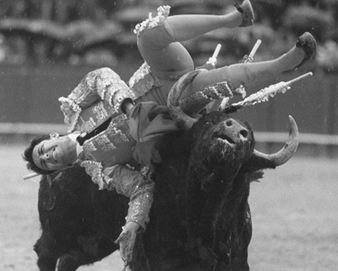

Bullfights. Participants in a bullfight include the matadors, their assistants (the banderilleros and picadors) and the bulls. When the bull first enters the arena from the bull pen gate, the matador attracts its attention with a series of passes with his large cape. The bull is attracted by the movement of the cape, not the colour, since bulls are colour-blind. The matador’s reputation is based on how close he gets to the horns of the bull. These fighting bulls have been bred and trained for centuries for their aggressiveness. The next part of the bullfight involves the weakening of the bull by mounted picadors placing lances in the bull, and then banderilleros, working on foot, placing barbed sticks called banderillas in the bull’s shoulder in order to lower the bull’s head for the kill.

The final stage of the fight involves the matador trying to kill the bull by inserting his sword blade between the shoulder blades of the bull into the aorta. This stage involves many formalized passes with the cape before the final kill. The greater the risks taken by the matador, the greater the acclaim, and of course the greater the risk of being gored (see figure 1). Bullfighters generally receive at least one goring per season, which could involve as many as 100 bullfights per year per matador.

Figure 1. Bullfighting.

El Pais

The primary hazard facing the matadors and their assistants is being gored or even killed by the bull. Another potential hazard is tetanus from being gored. One epidemiological study in Madrid, Spain, indicated that only 14.9% of bullfighting professionals had complete anti-tetanus vaccination, while 52.5% had suffered occupational injuries (Dominguez et al. 1987). Few precautions are taken. The mounted picadors wear steel leg armour. Otherwise, the bullfighting professionals depend on the training and skills of themselves and their horses. One essential precaution is adequate planning for onsite emergency medical care (see “Motion picture and television production” in this chapter).

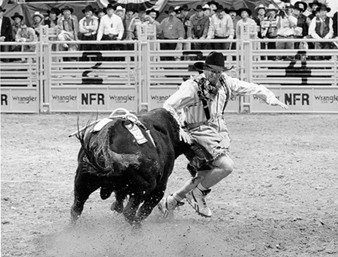

Rodeos. The most hazardous common rodeo events are bronco or bull riding and steer wrestling. In bronco or bull riding, the purpose is to stay on the bucking animal for a predetermined time. Bronco riding can be either bareback or with a saddle. In steer wrestling, a rider on horseback attempts to throw the steer to the ground by diving off the horse, grabbing the bull by its horns and wrenching it to the ground. Calf roping involves roping a calf from horseback, jumping off the horse and then hog-tying the front and back legs of the calf together in the shortest possible time.

Besides the rodeo contestants, those at risk include the pickup riders or outriders, whose role is to rescue the thrown rider and capture the animal, and the rodeo clowns, whose job is to distract the animal, especially bulls, to give the thrown rider a chance to escape (figure 2). They do this while on foot and dressed in a colourful costume to attract the animal’s attention. Hazards include being trampled, being gored by the bull’s horns, injuries from being bucked off, knee injuries from jumping off the horse, elbow injuries in bronco and bull riders from holding on to the animal with one hand and facial injuries from bulls tossing their heads back. Injuries also occur from bronco or bull riders being smashed against the sides of the chute while waiting for the gate to open and the animal to be released. Severe injuries and fatalities are not infrequent. Bull riders sustain 37% of all rodeo-related injuries (Griffin et al. 1989). In particular, brain and spinal cord injuries are of concern (MMWR 1996). One study of 39 professional rodeo cowboys showed a total of 76 elbow abnormalities in 29 bronco and bull riders (Griffin et al. 1989). They concluded that the injuries were a result of constant hyperextension of the arm gripping the animal, as well as injuries in falls.

Figure 2. Rodeo clown distracting a bull from a fallen rider.

Dan Hubbell

The main way of preventing injuries lies in the skills of the rodeo cowboys, pickup riders and rodeo clowns. Well-trained horses are also essential. Taping elbows and wearing elbow pads has also been recommended for bronco and bull riding. Safety vests, mouth guards and safety helmets are rare, but becoming more accepted. Face masks have occasionally been used for bull riding. As in bullfighting, an essential precaution is adequate planning for on-site emergency medical care.

In both rodeos and bullfighting, of course, the animal keepers, feeders and so on are also at risk. For more information on this aspect, see “Zoos and aquariums” in this chapter.

Circuses and Amusement and Theme Parks

The common product shared between circuses and amusement and theme parks is creating and providing entertainment for the public’s enjoyment. Circuses can take place in a large temporary tent equipped with bleachers or in permanent buildings. Attending a circus is a passive activity in which the customer views the various animal, clown and acrobatic acts from a seated position. Amusement and theme parks, on the other hand, are locations where customers actively walk around the park and can participate in a wide variety of activities. Amusement parks can have many different types of rides, exhibits, games of skill, sales booths and stores, grandstand shows and other types of entertainment. Theme parks have exhibits, buildings and even small villages that illustrate the particular theme. Costume characters, who are actors dressed in costumes illustrating the theme—for example, historical costumes in historic villages or cartoon costumes for parks with a cartoon theme—will participate in shows or walk around among the visiting crowds. Local country fairs are another type of event where activities can include rides, animal and other side shows, such as fire-eating, and agricultural and farm animal exhibitions and competitions. The size of the operation can be as small as one person running a pony cart ride in a parking lot, or as large as a major theme park employing thousands. The larger the operation, the more background services that can be present, including parking lots, sanitation facilities, security and other emergency services and even hotels.

Occupations vary widely as do the levels of skills required for individual tasks. People employed in these activities include ticket sellers, acrobatic performers, animal handlers, food service workers, engineers, costume characters and ride operators, among a long list of other workers. The occupational safety and health risks include many of those found in general industry and others that are unique to circuses and amusement and theme park operations. The following information provides a review of entertainment-related hazards and precautions found within this segment of the industry.

Acrobatics and Stunts

Circuses, in particular, have many acrobatic and stunt acts, including high-wire tightrope walking and other aerial acts, gymnastic acts, fire-juggling acts and displays of horsemanship. Amusement and theme parks can also have similar activities. Hazards include falls, misjudged clearances, improperly inspected equipment and physical fatigue due to multiple daily shows. Typical accidents involve muscular, tendon and skeletal injuries.

Precautions include the following: Performers should receive comprehensive physical conditioning, proper rest and a good diet, and show schedules should be rotated. All equipment, props, rigging, safety devices and blocking should be carefully reviewed before each performance. Show personnel should not perform when they are ill, injured or taking medication which may affect required abilities to safely meet the needs of the show.

Animal Handling

Animals are most commonly found in circuses and county fairs, although they can also be found in activities such as pony rides in amusement parks. Animals are found in circuses in wild-animal training acts, for example, with lions and tigers, horse riding acts and other trained animal acts. Elephants are used as show performers, rides, exhibits and work animals. In country fairs, farm animals such as pigs, cattle and horses are exhibited in competitions. In some places, exotic animals are displayed in cages and in such acts as snake handling. Hazards include the unpredictable characteristics of animals combined with the potential for animal handlers to become overly confident and let their guard down. Serious injury and death are possible in this occupation. Elephant handling is considered one of the most dangerous professions. Some estimates indicate there are approximately 600 keepers in the United States and Canada. During the course of an average year there will be one elephant handler killed. Venomous snakes, if used in snake-handling acts, can also be very dangerous, with possible fatalities from snake bites.

Precautions include intense and ongoing animal-handling training. It must be instilled in employees to remain on their guard at all times. The use of protected contact systems is recommended where keepers work alongside animals capable of causing serious injury or death. Protected contact systems always separate the animal handler and the animal by means of bars or closed-off areas. When animals perform on stage to live audiences, noise and other stimuli conditioning must be a part of the required safety training. With venomous reptiles, proper anti-venom antidotes and protective equipment such as gloves, leg guards, snake pincers and carbon dioxide bottles should be available. Care and feeding of animals when they are not being exhibited also requires careful attention on the part of the animal caretakers to prevent injury.

Costume Characters

Costume characters acting the role of cartoon figures or historical period characters often wear heavy and bulky costumes. They can act on stages or mingle with the crowds. Hazards are back and neck injuries associated with wearing such costumes with uneven weight distribution (figure 1). Other exposures are fatigue, heat-related problems, crowd pushing and hitting. See also “Actors”.

Figure 1. Worker wearing a heavy costume.

William Avery

Precautions include the following: Costumes should be correctly fitted to the individual. The weight load, especially above the shoulders, should be kept at a minimum. Costume characters should drink plenty of water during periods of warm weather. Interaction with the public should be of short duration because of the stress of such work. Character duties should be rotated, and non-costumed escorts should be with characters at all times to manage crowds.

Fireworks

Fireworks displays and pyrotechnics special effects can be a common activity (figure 2). Hazards can involve accidental discharge, non-planned explosions and fire.

Figure 2. Loading pyrotechnics for fireworks show.

William Avery

Precautions include the following: Only appropriately trained and licensed pyrotechnicians should detonate explosives. Storage, transportation and detonation procedures must be followed (figure 3). Applicable codes, laws and ordinances in the jurisdiction where operating must be adhered to. Pre-approved personal safety equipment and fire extinguishing equipment must be at the detonation site where there is immediate access.

Figure 3. Bunker storage for fireworks.

William Avery

Food Service

Food can be bought at circuses and amusement and theme parks from individuals with trays of food, at vendor carts, booths, or even restaurants. Hazards common to food service operations at these events involve serving large captive audiences during high periods of demand in a very short period of time. Falls, burns, cuts and repetitive motion trauma are not uncommon in this occupational classification. Carrying food around on trays can involve back injuries. The risks are increased during periods of high volume. A common example of injury occurring in high-volume food service areas is repetitive motion trauma that can result in tendinitis and carpal tunnel syndrome. One example of a job description where such injuries occur is an ice-cream scooper.

Precautions include the following: Increased staffing during high-volume periods is essential to the safety of the operation. Specific duties such as mopping, sweeping and cleaning should be addressed. Precautions for repetitive motion trauma: regarding the example given above, using softer ice cream can make scooping less strenuous, employees can be regularly rotated, scoops can be warmed to promote easier penetration of the ice cream and the use of ergonomically designed handles should be considered.

Scenery, Props and Exhibits

Stage shows, exhibits, booths, artificial scenery and buildings must be built. Hazards include many of the same hazards as found in construction, including electrocution, severe lacerations, and eye and other injuries associated with the use of power tools and equipment. The outdoor building and use of props, scenery and exhibits increases the potential hazards such as collapse if construction is inadequate. Handling of these components can result in falls and back and neck injuries (see also “Scenery shops” in this chapter).

Precautions include the following: The manufacturer’s warnings, safety equipment recommendations and safe operating instructions for power tools and machinery must be followed. The weight of props and their sections should be minimized to reduce the possibility of lifting-associated injuries. Props, scenery and exhibits designed for outdoor use must be reviewed for wind load ratings and other outdoor exposures. Props designed for use with live loads should be appropriately rated and the built-in safety factor verified. Fire rating of the material should be considered based on the intended use, and any fire regulations that may be applicable must be followed.

Ride Operators and Maintenance Personnel

There are a wide variety of amusement park rides, including Ferris wheels, roller coasters, water flume rides, looping boats and aerial tramways. Ride operators and maintenance personnel work in areas and under conditions where there are increased risks of serious injury. The exposures include electrocution, being struck by equipment and caught in or between equipment and machinery. Besides the rides, ride and maintenance personnel must also operate and maintain the associated electrical power plants and transformers.

Precautions include an effective programme that can reduce the potential for serious injury in a lock out, tag out and block out procedure. This programme should include: personally assigned padlocks with single keys; written procedures for working on electrical circuitry, machinery, hydraulics, compressed air, water and other sources of possible energy release; and tests to ensure that the energy supply has been shut off. When more than one person is working on the same piece of equipment, each person should have and use his or her own lock.

Travelling Shows

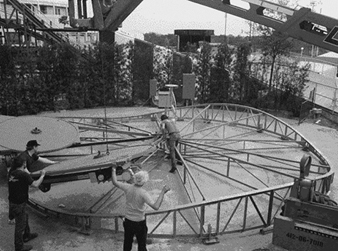

Circuses and many amusement rides can travel from one location to another. This can be by truck for small operations, or by train for large circuses. Hazards include falls, severed body parts and possible death during erection, dismantling or transportation of equipment (figure 4). A particular problem is expedited work procedures, resulting in skipping time-consuming safety procedures, in an effort to meet play date deadlines.

Figure 4. Erecting an amusement park ride with a crane.

William Avery

Precautions include the following: Employees must be well trained, exercise caution and follow manufacturer’s safety instructions for assembly, dismantling, loading, unloading and transportation of the equipment. When animals are used, such as an elephant to pull or push heavy equipment, additional safety precautions are required. Equipment such as cables, ropes, hoists, cranes and fork-lifts should be inspected before each use. Over-the-road drivers must follow highway transportation safety guidelines. Employees will require additional training in safety and emergency procedures for train operations where animals, personnel and equipment travel together.

Parks and Botanical Gardens

The occupational safety and health hazards for those who work in parks and botanical gardens fall in the following general categories: environmental, mechanical, biological or chemical, vegetation, wildlife and caused by human beings. The risks differ depending on where the site is located. Urban, suburban, developed or undeveloped wildland will differ.

Environmental Hazards

As parks and garden personnel are found in all geographical areas and generally spend a great deal, if not all, of their working time outdoors, they are exposed to the widest variety and extremes of temperature and climatic conditions, with the resultant risks ranging from heat stroke and exhaustion to hypothermia and frostbite.

Those who work in urban areas may be in facilities where vehicular traffic is significant and may be exposed to toxic exhaust emissions such as carbon monoxide, unburned carbon particles, nitrous oxide, sulphuric acid, carbon dioxide and palladium (from the breakdown of catalytic converters).

Because some facilities are located in the higher elevations of mountainous regions, altitude sickness may be a risk if an employee is new to the area or is prone to high or low blood pressure.

Park area workers are usually called upon to perform search and rescue and disaster control activities during and following natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, flooding, volcanic eruptions and the like affecting their area, with all of the risks inherent in such events.

It is essential that all personnel be thoroughly trained in the potential environmental risks inherent in their areas and be provided with the proper clothing and equipment, such as adequate cold- or hot-weather gear, water and rations.

Mechanical Hazards

Personnel in parks and gardens are called upon to be thoroughly familiar with and operate an extremely wide variety of mechanical equipment, ranging from small hand tools and power tools and powered lawn and garden equipment (mowers, thatchers, rototillers, chainsaws, etc.) to heavy equipment such as small tractors, snow ploughs, trucks and heavy construction equipment. Additionally, most facilities have their own shops equipped with heavy power tools such as table saws, lathes, drill presses, air pressure pumps and so on.

Employees must be thoroughly trained in the operation, hazards and safety devices for all types of equipment they could potentially operate, and be provided and trained in the use of the appropriate personal protection equipment. Since some personnel may also be required to operate or ride the full range of motor vehicles, and fixed- or rotary-wing aircraft, they must be thoroughly trained and licensed, and regularly tested. Those that ride as passengers must have knowledge of the risks and training in safe operation of such equipment.

Biological and Chemical Hazards

Continuous, close contact with the general public is inherent in almost every occupation in park and garden work. The risk of contracting viral or bacterial diseases is always present. Additionally, the risk of contact with infected wildlife that carry rabies, psitticosis, Lyme disease and so on is present.

Park and botanical garden workers are exposed to various amounts and concentrations of pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, fertilizers and other agricultural chemicals, as well as toxic paints, thinners, varnishes, lubricants and so on used in maintenance and transport work and equipment.

With the proliferation of illegal drugs, it is becoming common for personnel in national parks and forests to come across illegal drug-manufacturing laboratories. The chemicals found in these can cause death or permanent neurological damage. Personnel in urban and rural areas may also encounter discarded drug paraphernalia such as used hypodermic syringes, needles, spoons and pipes. If any of these punctures the skin or enters the body, illness ranging from hepatitis to HIV could result.

Thorough training in the risks and preventive measures is essential; regular physical examinations should be provided and immediate medical attention sought if a person is so exposed. It is essential that the type and duration of exposure be recorded, if possible, to be given to the treating physician. Whenever illegal drug paraphernalia is encountered personnel should not touch it but rather should secure the area and refer the matter to trained law enforcement personnel.

Vegetation Hazards

Most types of vegetation pose no health risk. However, in wildland areas (and some urban and suburban park areas) poisonous plants such as poison ivy, poison oak and poison sumac can be found. Health problems ranging from a minor rash to a severe allergic reaction can result, depending on the susceptibility of the individual and the nature of the exposure.

It should be noted that roughly 22% of the total population suffers from allergic reactions of one form or another, ranging from mild to severe; an allergic individual may respond to only a few substances, or to many hundreds of different types of vegetation and animal life. Such reactions can result in death, in extreme cases, if immediate treatment is not found.

Prior to working in any environment with plant life, it should be determined whether an employee has any allergies to potential allergens and should take or carry appropriate medication.

Personnel should also be cognizant of plant life that is not safe to ingest, and should know the signs of ingestion illness and the antidotes.

Wildlife Hazards

Parks workers will encounter the full spectrum of wildlife that exists around the world. They must be familiar with the types of animals, their habits, the risks and, where necessary, the safe handling of the wildlife expected to be encountered. Wildlife ranges from urban domestic animals, such as dogs and cats, to rodents, insects and snakes, to wildland animals and bird species including bears, mountain lions, poisonous snakes and spiders, and so on.

Proper training in the recognition and handling of wildlife, including the diseases affecting such wildlife, should be provided. Appropriate medical response kits for poisonous snakes and insects should be available, along with training in how to use them. In remote wildland areas, it may be necessary to have personnel trained in the use of, and be equipped with, firearms for personal protection.

Human-caused Hazards

In addition to the aforementioned risk of contact with a visitor having a contagious illness, a major share of the risks faced by personnel who work in the parks, and to a lesser degree botanical gardens, are the result of either accidental or deliberate action of facilities visitors. Those risks range from the need of park employees to perform search and rescue activities for lost or injured visitors (some in the most remote and dangerous environments) to responding to acts of vandalism, drunkenness, fighting and other disruptive activities, including assault on park or garden employees. Additionally, the park or garden employee is at risk of vehicular accidents caused by visitors or others who are driving by or in the vicinity of the employee.

Approximately 50% of all wildland fires have a human cause, attributable to either arson or negligence, to which the park employee may be required to respond.

Wilful damage or destruction of public property is also, unfortunately, a risk the park or garden employee may well be required to respond to and repair, and, depending on the type of property and degree of damage, a significant safety risk may be present (i.e., damage to wilderness trails, foot bridges, interior doors, plumbing equipment and so on).

Personnel who work with the environment are, generally, sensitive and attuned to the outdoors and to preservation. As a result, many such personnel suffer from varying degrees of stress and related illnesses because of the unfortunate actions of some of those who visit their facilities. It is important, therefore, to be aware of the onset of stress and take remedial action. Classes in stress management are helpful for all such personnel.

Violence

Violence in the workplace is, unfortunately, becoming an increasing common risk and cause of injury. There are two general classes of violence: physical and psychological. The types of violence range from simple verbal threats to mass murder, as evidenced by the 1995 bombing of the US federal office building, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. In 1997 a tribal police officer was killed while trying to serve a warrant on a Southwest Indian reservation. There is also a less discussed, but common, psychological violence that has been classed euphemistically as “office politics” that can have equally debilitating effects.

Physical. In the United States, attacks on federal, state and local governmental personnel who work in remote and semi-remote parks and recreation areas are not uncommon. The majority of these result in injury only, but some involve assaults with dangerous weapons. There have been instances where disgruntled members of the public have entered federal land-managing agencies’ offices brandishing firearms, threatened the employees and had to be restrained.

Such violence can result in injury ranging from minor to fatal. It can be inflicted by unarmed assault or the use of the widest variety of weapons, ranging from simple club and stick to handguns, rifles, knives, explosives and chemicals. It is not uncommon for such violence to be inflicted upon the vehicles and structures owned or used by the governmental agency that operates the park or recreational facility.

It is also not uncommon for disgruntled or dismissed employees to seek retaliation against current or former supervisors. It is also becoming common for outdoor recreation, forest and park employees to encounter persons growing and/or manufacturing illegal drugs in remote areas. Such persons do not hesitate to resort to violence to protect their perceived territory. Park and recreation personnel, particularly those involved in law enforcement, are required to deal with persons under the influence of drugs or alcohol who break the law and become violent when apprehended.

Psychological. Not as well publicized, but in some instances equally damaging, is psychological violence. Commonly called “office politics”, it has been in use probably since the beginning of civilization to gain status over co-workers, gain an advantage in the workplace and/or weaken a perceived opponent. It consists of destroying the credibility of another person or group, usually without that other person or group being aware that it is being done.

In some instances, it is done openly, through the media, legislative bodies and so on, in an attempt to gain political advantage (for example, destroying the credibility of a governmental agency in order to cut its funding).

This usually has a significant negative result on the morale of the individual or group involved and, in rare, extreme instances, can cause a recipient of the violence to take his or her own life.

It is not uncommon for victims of violence to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, which may affect them for years. It has the same effect as “shell shock” among military personnel who have experienced prolonged and intense combat. It may require extensive psychological counselling.

Protective measures. Because of the constantly increased risk of encountering violence in the workplace, it is essential that employees receive extensive training in the recognition and avoidance of potentially dangerous situations, including training in how to deal with persons who are violent or out of control.

- Where possible, additional security needs to be added to high-density occupancy areas.

- Employees who work away from a standard office or shop location should be provided with two-way radio communication to be able to summon help when needed.

- In some instances, it may be necessary to train employees in the use of firearms and arm them for self-protection.

- Each agency responsible for managing park or outdoor recreation areas should conduct an annual security survey of all its facilities to determine current risk and what measures are necessary to protect employees.

- Management at all levels needs to exercise extra vigilance to counter the psychological risk whenever it occurs, seek out and correct unfounded rumours and assure that all employees have accurate facts concerning the operation and future plans of their agency and workplace.

Post-incidence assistance. It is equally essential, not only for the affected employees or employers, but all agency employees as well, that any employee subjected to on-the-job violence be given not only prompt medical attention, but equally prompt psychological assistance and stress counselling. The effects of such violence can remain with the employee long after the physical wounds heal and can have a significant negative effect on his or her ability to function in the workplace.

As the population increases, the incidence of violence will increase. Preparation and prompt and effective response are, at present, the only remedies open to those at risk.

Conclusion

Because personnel are required to work in all types of environments, good health and physical fitness is essential. A consistent regimen of moderate physical training should be adhered to. Regular physical examinations, geared to the type of work to be performed, should be obtained. All personnel should be completely trained in types of work to be performed, the hazards involved and hazard avoidance.

Equipment should be maintained in sound operating condition.

All personnel expected to work in remote areas should carry two-way radio communication equipment and be in regular contact with a base station.

All personnel should have basic—and if possible, advanced—first aid training, including cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, in the event a visitor or co-worker is injured and medical help is not immediately available.

Zoos and Aquariums

Zoological gardens, wildlife parks, safari parks, bird parks and collections of aquatic wildlife share similar methods for the maintenance and handling of exotic species. Animals are held for exhibition, as an educational resource, for conservation and for scientific study. Traditional methods of caging animals and preparing aviaries for birds and tanks for water creatures remain common, but more modern, progressive collections have adopted different enclosures designed to meet more of the needs of particular species. The quality of space accorded to an animal is more important than the quantity, however, which has consequential beneficial effects on keeper safety. The danger to keepers is often related to the size and natural ferocity of the species attended, but many other factors can affect the danger.

The main animal groupings are mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Problem areas that are common to all the animal groups are toxins, diseases that are contractible from animals (zoonoses) and changing animal moods.

Mammals

Mammals’ varied forms and habits require a wide range of husbandry techniques. The largest land forms are herbivorous, such as elephants, and are limited in their ability to climb, jump, burrow or gnaw, so their control is similar to domestic forms. Remote control of gates can offer high degrees of safety. Large predators such as big cats and bears require enclosures with wide margins of safety, double entry doors and in-built catch-ups and crushes. Agile climbing and jumping species pose special problems to keepers, who lack comparable mobility. The use of electric shock fence wiring is now widespread. Capture and handling methods include corralling, nets, crushing, roping, sedation and immobilization with drugs injected by dart.

Birds

Few birds are too large to be restrained by gloved hands and nets. The largest flightless birds—ostriches and cassowaries—are strong and have a very dangerous kick; they require crating for restraint.

Reptiles

Large carnivorous reptile species have violent strike attack capability; many snakes do too. Captive specimens may seem docile and induce keeper complacency. An attacking large constricting snake can overwhelm and suffocate a panicking keeper of much greater weight. A few venomous snakes can “spit”; thus eye protection against them should be mandatory. Restraint and handling methods include nets, bags, hooks, grabs, nooses and drugs.

Amphibians

Only a large giant salamander or big toad can give an unpleasant bite; otherwise risks from amphibians are from toxin excretion.

Fish

Few fish specimens are hazardous except for venomous species, electric eels and bigger predatory forms. Careful netting minimizes risk. Electric and chemical stunning may be occasionally appropriate.

Invertebrates

Some lethal invertebrate species are kept which require indirect handling. Mis-identification and specimens hidden by camouflage and small size can endanger the unwary.

Toxins

Many animal species have evolved complex poisons for feeding or defence, and deliver them by biting, stinging, spitting and secretion. Delivered quantities may vary from the inconsequential to lethal doses. Worst case scenarios should be the model for accident anticipation procedures. Single keeper exposure to lethal species should not be practised. Husbandry must include risk evaluation, unambiguous warning signs, restriction of handling to those trained, maintenance of stocks of antidotes (if any) in close liaison with local trained medical practitioners, predetermination of handler reaction to antidotes and an efficient alarm system.

Zoonoses

A good animal health programme and personal hygiene will keep the risk from zoonoses very low. However, there are many which are potentially lethal, such as rabies, which is untreatable in later stages. Almost all are avoidable, and treatable if diagnosed correctly early enough. As with work elsewhere, the incidence of allergy-related illness is rising and it is best treated by non-exposure to the irritant when identified.

“Non-venomous” bites and scratches require careful attention, as even a bite which appears not to break skin can lead to rapid blood poisoning (septicaemia). Carnivore and monkey bites should be especially suspect. An extreme example is the bite of a komodo dragon; the microflora in its saliva are so virulent that bitten large prey that escapes an initial attack will rapidly die from shock and septicaemia.

Routine prophylaxis against tetanus and hepatitis may be appropriate for many staff.

Moods

Animals can give an infinite variety of responses, some very dangerous, to close human presence. Observable mood changes can alert keepers to danger, but few animals show signs readable by humans. Moods can be influenced by a combination of seen and unseen stimuli such as season, day length, time of day, sexual rhythms, upbringing, hierarchy, barometric pressure and high-frequency noise from electrical equipment. Animals are not production line machines; they may have predictable patterns of behaviour but all have the capacity to do the unexpected, against which even the most skilled attendant must guard.

Personal safety

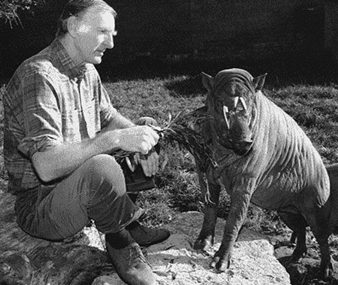

Risk appreciation should be taught by the skilled to the inexperienced. An undiminishing high level of caution will enhance personal safety, particularly, for example, when food is offered to larger carnivores. Animal responses will vary to different keepers, especially to those of different sex. An animal submissive to one person may attack another. The understanding and use of body language can enhance safety; animals naturally understand it better than humans. Voice tone and volume can calm or cause chaos (figure 1).

Figure 1. Handling animals with voice and body language.

Ken Sims

Clothing should be chosen with special care, avoiding bright, flapping material. Gloves may protect and reduce handling stress but are inappropriate for handling snakes because tactile sensitivity is reduced.

If keepers and other staff are expected to manage trespassing, violent or other problem visitors, they should be schooled in people management and have back-up on call to minimize risks to themselves.

Regulations

Despite the variety of potential risks from exotic species, the greater workplace hazards are conventional ones arising from plant and machinery, chemicals, surfaces, electricity and so on, so standard health and safety regulations must be applied with common sense and regard for the unusual nature of the work.

Museums and Art Galleries

Museums and art galleries are a popular source of entertainment and education for the general public. There are many different types of museums, such as art, history, science, natural history and children’s museums. The exhibits, lectures and publications offered to the public by museums, however, are only one part of the function of museums. The broad mission of museums and art galleries is to collect, conserve, study and display items of artistic, historical, scientific or cultural importance. Supportive research (fieldwork, literary and laboratory) and behind-the-scenes collection care typically represent the largest proportion of work activities. Collections on display generally represent a small fraction of the total acquisitions of the museum or gallery, with the remainder in on-site storage or on loan to other exhibits or research projects. Museums and galleries may be stand-alone entities or affiliated with larger institutions such as universities, government agencies, armed services installations, park service historic sites or even specific industries.

A museum’s operations can be divided into several main functions: general building operations, exhibit and display production, educational activities, collection management (including field studies) and conservation. Occupations, which may overlap depending on size of staff, include building maintenance trades and custodians, carpenters, curators, illustrators and artists, librarians and educators, scientific researchers, specialized shipping and receiving and security.

General Building Operations

The operation of museums and galleries poses potential safety and health hazards both common to other occupations and unique to museums. As buildings, museums are subject to poor indoor air quality and to risks associated with maintenance, repair, custodial and security activities of large public buildings. Fire prevention systems are critical to protect the lives of staff and a multitude of visitors, as well as the priceless collections.

General tasks involve custodians; heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) specialists and boiler engineers; painters; electricians; plumbers; welders; and machinists. Safety hazards include slips, trips and falls; back and limb strains; electrical shock; and fires and explosions from compressed gas cylinders or hot work. Health hazards include exposures to hazardous materials, noise, metal fumes, flux fumes and gases, and ultraviolet radiation; and dermatitis from cutting oils, solvents, epoxies and plasticizers. Custodial staff are exposed to splash hazards from diluting cleaning chemicals, chemical reactions from improperly mixed chemicals, dermatitis, inhalation hazards from dry sweeping of lead paint chips or residual preservative chemicals in collection storage areas, injury from broken laboratory glassware or working around sensitive laboratory chemicals and equipment, and biological hazards from cleaning building exteriors of bird debris.

Older buildings are prone to mould and mildew growth and poor indoor air quality. They often lack exterior wall vapour barriers and have air handling systems which are old and difficult to maintain. Renovation may lead to uncovering material hazards in both centuries-old buildings and modern ones. Lead paints, mercury linings on old mirrored surfaces and asbestos in decorative finishes and insulation are some examples. With historic buildings, the need to preserve historic integrity must be balanced against design requirements of life safety codes and accommodations for persons with disabilities. Exhaust ventilation system installations should not destroy historic facades. Rooflines or skyline restrictions in historic districts may pose serious challenges to construction of exhaust stacks with sufficient height. Barriers used to separate construction areas often must be free-standing units that cannot be attached to walls that have historic features. Renovation should not mar underlying supports which may consist of valuable wood or finishes. These restrictions may lead to increased dangers. Fire detection and suppression systems and fire-rated construction are essential.

Precautions include the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for eyes, face, head, hearing and respiration; electrical safety; machine guards and lock-out/tag-out programmes; good housekeeping; compatible hazardous material storage and secure compressed gas cylinders; fire detection and suppression systems; dust collectors, local exhaust and use of high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtered vacuum cleaners; safe lifting and material handling training; fork-lift safety; use of hoists, slings and hydraulic lifts; chemical spill control; safety showers and eye washes; first aid kits; and hazard communication and employee training programmes in hazards of materials and jobs (particularly for custodians in laboratories) and means for protection.

Exhibit and Display Production

The production and installation of museum exhibits and displays can involve a wide range of activities. For example, an animal exhibit in a natural history museum could involve the production of display cases; the construction of a reproduction of the animal’s natural habitat; the fabrication of the animal model itself; written, oral and illustrated materials to accompany the exhibit; appropriate lighting; and more. Processes involved in the exhibit production can include: carpentry; metalworking; working with plastics, plastics resins and many other materials; graphic arts; and photography.

Exhibit fabrication and graphics shops share similar risks with general woodworkers, sculptors, graphic artists, metalworkers and photographers. Specific health or safety risks may arise from installation of exhibits in halls without adequate ventilation, cleaning of display cases containing residues of hazardous treatment materials, formaldehyde exposure during photography set-up of fluid collection specimens and high-speed cutting of wood treated with fire retardant, which may liberate irritating acid gases (oxides of sulphur, phosphorus).

Precautions include appropriate personal protective equipment, acoustic treatment and local exhaust controls on woodworking machinery; adequate ventilation for graphics tables, silkscreen wash booths, paint-mixing areas, plastics resin areas, and photo development; and use of water-based ink systems.

Educational Activities

Museum educational activities can include lectures, distribution of publications, hands-on arts and science activities and more. These can be directed either towards adults or children. Arts and science activities can often involve use of toxic chemicals in rooms not equipped with proper ventilation and other precautions, handling arsenic-preserved stuffed birds and animals, electrical equipment and more. Safety risks may exist for both museum education staff and participants, particularly children. Such programmes should be evaluated to determine what types of precautions are needed and whether they can be done safely in the museum setting.

Art and Artefact Collections Management

Collections management involves field collection or acquisition, inventory control, proper storage techniques, preservation and pest management. Fieldwork can involve digging on archaeological expeditions, preserving botanical, insect and other specimens, making casts of specimens, drilling fossil rocks and more. The duties of curatorial staff in the museum include handling the specimens, examining them with a variety of techniques (e.g., microscopy, x ray), pest management, preparing them for exhibits and handling travelling exhibitions.

Hazards can occur at all stages of collections management, including those associated with field work, hazards inherent in the handling of the object or specimen itself, residues of old preservation or fumigation methods (which may not have been well documented by the original collector) and hazards associated with pesticide and fumigant application. Table 1 gives the hazards and precautions associated with some of these operations.

Table 1. Hazards and precautions of collection management processes.

|

Process |

Hazards and precautions |

|

Field work and handling of specimens |

Ergonomic injuries from repetitive drilling on fossil rock and heavy lifting; biohazards from surface cleaning of bird debris, allergic response (pulmonary and dermal) from insect frass, handling both living and dead specimens, particularly birds and mammals (plaque, Hanta virus) and other diseased tissues; and chemical hazards from preserving media. |

|

Precautions include ergonomic controls; HEPA vacuums for control of detritus allergens, insect eggs, larvae; universal precautions for avoiding staff exposure to animal disease agents;.and adequate ventilation or respiratory protection when handling hazardous preserving agents. |

|

|

Taxidermy and osteological preparation |