Myers, Melvin L.

Address: National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health, CDC, Office of Extramural Coordination & Special Projects, 1293 Berkeley Road, Avondale Estates, GA 30002-1517

Country: United States

Phone: 1 (404) 288-7085

Fax: 1 (404) 639-2196

E-mail: mlm2@cdc.gov

Past position(s): Special Assistant to the Director, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; Director, Office of Program Planning and Evaluation, National Institute for Occupational; Safety and Health; Technical Assistant to the Deputy Assistant Director, Office of Research and Development, Environmental Protection Agency

Education: BS, 1967, University of Idaho; MPA, 1977, Indiana University

Areas of interest: Safety and health in agriculture; safety and health in construction work; occupational and environmental health policy; history of occupational safety and health

Plantations

Adapted from 3rd edition, “Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety”.

The term plantation is widely used to describe large-scale units where industrial methods are applied to certain agricultural enterprises. These enterprises are found primarily in the tropical regions of Asia, Africa and Central and South America, but they are also found in certain subtropical areas where the climate and soil are suitable for the growth of tropical fruits and vegetation.

Plantation agriculture includes short-rotation crops, such as pineapple and sugar cane, as well as tree crops, such as bananas and rubber. In addition, the following tropical and subtropical crops are usually considered as plantation crops: tea, coffee, cocoa, coconuts, mango, sisal and palm nuts. However, large-scale cultivation of certain other crops, such as rice, tobacco, cotton, maize, citrus fruits, castor beans, peanuts, jute, hemp and bamboo, is also referred to as plantation cultivation. Plantation crops have several characteristics:

- They are either tropical or subtropical products for which an export market exists.

- Most require prompt initial processing.

- The crop passes through few local marketing or processing centres before reaching the consumer.

- They typically require a significant investment of fixed capital, such as processing facilities.

- They generate some activity for most of the year, and thus offer continuous employment.

- Monocropping is typical, which allows for specialization of technology and management.

While the cultivation of the various plantation crops requires widely different geographic, geological and climatic conditions, practically all of them thrive best in areas where climatic and environmental conditions are arduous. In addition, the extensive nature of plantation undertakings, and in most cases their isolation, has given rise to new settlements that differ considerably from indigenous settlements (NRC 1993).

Plantation Work

The main activity on a plantation is the cultivation of one of two kinds of crops. This involves the following kinds of work: soil preparation, planting, cultivation, weeding, crop treatment, harvesting, transportation and storage of produce. These operations entail the use of a variety of tools, machines and agricultural chemicals. Where virgin land is to be cultivated, it may be necessary to clear forest land by felling trees, uprooting stumps and burning off undergrowth, followed by ditch and irrigation channel digging. In addition to the basic cultivation work, other activities may also be carried out on a plantation: raising livestock, processing crops and maintaining and repairing buildings, plants, machinery, implements, roads and railway tracks. It may be necessary to generate electricity, dig wells, maintain irrigation trenches, operate engineering or woodworking shops and transport products to the market.

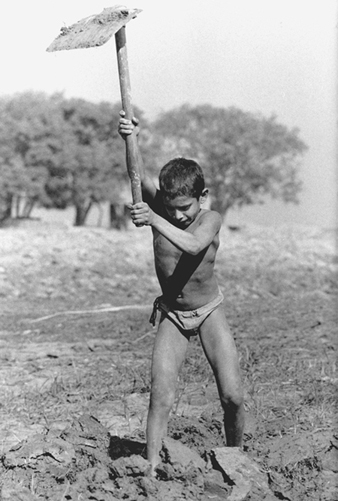

Child labour is employed on plantations around the world. Children work with their parents as part of a team for task-based compensation, or they are employed directly for special plantation jobs. They typically experience long and arduous working hours, little safety and health protection and inadequate diet, rest and education. Rather than direct employment, many children are recruited as labour through contractors, which is common for occasional and seasonal tasks. Employing labour through contracted intermediaries is a long-standing practice on plantations. The plantation management thus does not have an employer- employee relationship with the plantation workers. Rather, they contract with the intermediary to supply the labour. Generally, conditions of work for contract labour are inferior to those of directly employed workers.

Many plantation workers are paid based upon the tasks performed rather than the hours worked. For example, these tasks may include lines of sugar cane cut and loaded, number of rubber trees tapped, rows weeded, bushels of sisal cut, kilograms of tea plucked or hectares of fertilizer applied. Conditions such as climate and terrain may affect the time to complete these tasks, and whole families may work from dawn to dusk without taking a break. The majority of countries where plantation commodities are grown report that plantation employees work more than 40 hours per week. Moreover, most plantation workers move to their work location on foot, and since plantations are large, much time and effort are expended on travel to and from the job. This travel can take hours each way (ILO 1994).

Hazards and Their Prevention

Work on plantations involves numerous hazards relating to the work environment, the tools and equipment used and the very nature of the work. One of the first steps toward improving safety and health on plantations is to appoint a safety officer and form a joint safety and health committee. Safety officers should assure that buildings and equipment are kept safe and that work is performed safely. Safety committees bring management and labour together in a common undertaking and enable the workers to participate directly in improving safety. Safety committee functions include developing work rules for safety, participating in injury and disease investigations and identifying locations that place workers and their families in danger.

Medical services and first aid materials with adequate instruction should be provided. Medical doctors should be trained in the recognition of occupational diseases related to plantation work including pesticide poisoning and heat stress. A risk survey should be implemented on the plantation. The purpose of the survey is to comprehend risk circumstances so that preventive action can be taken. The safety and health committee can be engaged in the survey along with experts including the safety officer, the medical supervisor and inspectors. Table 1 shows the steps involved in a survey. The survey should result in action including the control of potential hazards as well as hazards that have resulted in an injury or disease (Partanen 1996). A description of some potential hazards and their control follow.

Table 1. Ten steps for a plantation work risk survey

- Define the problem and its priority.

- Find existing data.

- Justify the need for more data.

- Define survey objectives, design, population, time and methods.

- Define tasks and costs, and their timing.

- Prepare protocol.

- Collect data.

- Analyse data and assess risks.

- Publish results.

- Follow up.

Source: Partanen 1996.

Fatigue and climate-related hazards

The long hours and demanding work make fatigue a major concern. Fatigued workers may be unable to make safe judgements; this may lead to incidents that can result in injuries or other inadvertent exposures. Rest periods and shorter workdays can reduce fatigue.

Physical stress is increased by heat and relative humidity. Frequent water consumption and rest breaks help to avoid problems with heat stress.

Tool and equipment-related injuries

Poorly designed tools will often result in poor work posture, and poorly sharpened tools will require greater physical effort to complete tasks. Working in a bent or stooping position and lifting heavy loads imposes strain on the back. Working with arms above the shoulder can cause upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders (figure 1). Proper tools should be selected to eliminate poor posture, and they should be well maintained. Heavy lifting can be reduced by lessening the weight of the load or engaging more workers to lift the load.

Figure 1. Banana cutters at work on "La Julia" plantation in Ecuador

Injuries can result from improper uses of hand tools such as machetes, scythes, axes and other sharp-edged or pointed tools, or portable power tools such as chain-saws; poor positioning and disrepair of ladders; or unsuitable replacements for broken ropes and chains. Workers should be trained in the proper use and maintenance of equipment and tools. Appropriate replacements should be provided for broken or damaged tools and equipment.

Unguarded machinery can entangle clothing or hair and can crush workers and result in serious injury or death. All machines should have safety built in, and the possibility of dangerous contact with moving parts should be eliminated. A lockout/tagout programme should be in effect for all maintenance and repair.

Machinery and equipment are also sources of excessive noise, resulting in hearing loss among plantation workers. Hearing protection should be used with machinery with high levels of noise. Low noise levels should be a factor in selecting equipment.

Vehicle-related injuries

Plantation roadways and paths may be narrow, thus presenting the hazard of head-on crashes between vehicles or overturns off the side of the road. Safe boarding of transport vehicles including trucks, tractor- or animal-drawn trailers and railways should be ensured. Where two-way roads are used, wider passages should be provided at suitable intervals to allow vehicles to pass. Adequate railing should be provided on bridges and along precipices and ravines.

Tractors and other vehicles pose two principal dangers to workers. One is tractor overturns, which commonly result in the fatal crushing of the operator. Employers should ensure that rollover protective structures are mounted on tractors. Seat-belts should also be worn during tractor operation. The other major problem is vehicle run-overs; workers should remain clear of vehicle travel paths, and extra riders should not be allowed on tractors unless safe seating is available.

Electricity

Electricity is used on plantations in shops and for processing crops and lighting buildings and grounds. Improper use of electric installations or equipment can expose workers to severe shocks, burns or electrocutions. The danger is more acute in damp places or when working with wet hands or clothing. Wherever water is present, or for electrical outlets outdoors, ground fault interrupter circuits should be installed. Wherever thunderstorms are frequent or severe, lightning protection should be provided for all plantation buildings, and workers should be trained in ways to minimize their danger of being struck and to locate safe refuges.

Fires

Electricity as well as open flames or smouldering cigarettes can provide the ignition source for fuel or organic dust explosions. Fuels—kerosene, gasoline or diesel fuel—can cause fires or explosions if mishandled or improperly stored. Greasy and combustible waste poses a risk of fire in shops. Fuels should be kept clear of any ignition source. Flameproof electrical devices and appliances should be used wherever flammables or explosives are present. Fuses or electrical breaker devices should also be used in electrical circuits.

Pesticides

The use of toxic agrochemicals is a major concern, particularly during the intensive use of pesticides, including herbicides, fungicides and insecticides. Exposures can take place during agricultural production, packaging, storage, transport, retailing, application (often by hand or aerial spraying), recycling or disposal. Risk of exposure to pesticides can be aggravated by illiteracy, poor or faulty labelling, leaking containers, poor or no protective gear, dangerous reformulations, ignorance of the hazard, disregard of rules and a lack of supervision or technical training. Workers applying pesticides should be trained in pesticide use and should wear appropriate clothing and respiratory protection, a particularly difficult behaviour to enforce in tropical areas where protective equipment can add to the heat stress of the wearer (figure 2 ). Alternatives to pesticide use should be a priority, or less toxic pesticides should be used.

Figure 2. Protective clothing worn when applying pesticides

Animal-inflicted injuries and illnesses

On some plantations, draught animals are used for dragging or carrying loads. These animals include horses, donkeys, mules and oxen. These types of animals have injured workers by kicking or biting. They also potentially expose workers to zoonotic diseases including anthrax, brucellosis, rabies, Q-fever or tularaemia. Animals should be well trained, and those that exhibit dangerous behaviour should not be used for work. Bridles, harnesses, saddles and so on should be used and maintained in good condition and be properly adjusted. Diseased animals should be identified and treated or disposed of.

Poisonous snakes may be present on the ground or some species may fall from trees onto workers. Snakebite kits should be provided to workers and emergency procedures should be in place for obtaining medical assistance and the appropriate anti-venom drugs should be available. Special hats made of hard materials that are capable of deflecting snakes should be provided and worn in locations where snakes drop on their victims from trees.

Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases can be transmitted to plantation workers by rats that infest buildings, or by drinking water or food. Unsanitary water leads to dysentery, a common problem among plantation workers. Sanitary and washing facilities should be installed and maintained in accordance with national legislation, and safe drinking water consistent with national requirements should be provided to workers and their families.

Confined spaces

Confined spaces, such as silos, can pose problems of toxic gases or oxygen deficiency. Good ventilation of confined spaces should be assured prior to entry, or appropriate respiratory protective equipment should be worn.

General Profile

Overview

Twelve millennia ago, humankind moved into the Neolithic era and discovered that food, feed and fibre could be produced from the cultivation of plants. This discovery has led to the food and fibre supply that feeds and clothes more than 5 billion people today.

This general profile of the agricultural industry includes its evolution and structure, economic importance of different crop commodities and characteristics of the industry and workforce. Agricultural workforce systems involve three types of major activities:

- manual operations

- mechanization

- draught power, provided specifically by those engaged in livestock rearing, which is discussed in the chapter Livestock rearing.

The agriculture system is shown as four major processes. These processes represent sequential phases in crop production. The agricultural system produces food, feed and fibre as well as consequences for occupational health and, more generally, public health and the environment.

Major commodities, such as wheat or sugar, are outputs from agriculture that are used as food, animal feed or fibre. They are represented in this chapter by a series of articles that address processes, occupational hazards and preventive actions specific to each commodity sector. Animal feed and forage are discussed in the chapter Livestock rearing.

Evolution and Structure of the Industry

The Neolithic revolution—the change from hunting and gathering to farming—started in three different places in the world. One was west and southwest of the Caspian Sea, another was in Central America and a third was in Thailand near the Burmese border. Agriculture started in about 9750 BC at the latter location, where seeds of peas, beans, cucumbers and water chestnuts have been found. This was 2,000 years before true agriculture was discovered in the other two regions. The essence of the Neolithic revolution and, thus, agriculture is the harvesting of plant seeds, their reintroduction into the soil and cultivation for another harvest.

In the lower Caspian area, wheat was the early crop of choice. As farmers migrated, taking wheat seed with them, the weeds in other regions were discovered to also be edible. These included rye and oats. In Central America, where maize and beans were the staples, the tomato weed was found to bear nutritious food.

Agriculture brought with it several problems:

- Weeds and other pests (insects in the fields and mice and rats in the granaries) became a problem.

- Early agriculture concerned itself with taking all that it could from the soil, and it would take 50 years to naturally replenish the soil.

- In some places, the stripping of growth from the soil would turn the land to desert. To provide water to crops, farmers discovered irrigation about 7,000 years ago.

Solutions to these problems have led to new industries. Ways to control weeds, insects and rodents evolved into the pesticide industry, and the need to replenish the soil has resulted in the fertilizer industry. The need to provide water for irrigation has spawned systems of reservoirs and networks of pipes, canals and ditches.

Agriculture in the developing nations consists principally of family-owned plots. Many of these plots have been handed down from generation to generation. Peasants make up half of the world’s rural poor, but they produce four-fifths of the developing countries’ food supply. In contrast, farms are increasing in size in the developed countries, turning agriculture into large-scale commercial operations, where production is integrated with processing, marketing and distribution in an agribusiness system (Loftas 1995).

Agriculture has provided subsistence for farmers and their families for centuries, and it has recently changed into a system of production agriculture. A series of “revolutions” has contributed to an increase in agricultural production. The first of these was the mechanization of agriculture, whereby machines in the fields substituted for manual labour. The second was the chemical revolution that, after the Second World War, contributed to the control of pests in agriculture, but with environmental consequences. A third was the green revolution, which contributed to North American and Asian productivity growth through genetic advances in the new varieties of crops.

Economic Importance

The human population has grown from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 5.6 billion in 1994, and the United Nations estimates that it will continue to grow to 7.9 billion by 2025. The continued rise in the human population will increase the demand for food energy and nutrients, both because of the increase in numbers of people and the global drive to combat malnutrition (Brown, Lenssen and Kane 1995). A list of nutrients derived from food is shown in table 1.

Table 1. Sources of nutrients

|

Nutrient |

Plant sources |

Animal sources |

|

Carbohydrates (sugars and starch) |

Fruits, cereals, root vegetables, pulses |

Honey, milk |

|

Dietary fats |

Oilseeds, nuts, and legumes |

Meat, poultry, butter, ghee, fish |

|

Proteins |

Pulses, nuts, and cereals |

Meat, fish, dairy products |

|

Vitamins |

Carotenes: carrots, mangoes, papaya |

Vitamin A: liver, eggs, milk |

|

Minerals |

Calcium: peas, beans |

Calcium: milk, meat, cheese |

Source: Loftas 1995.

Agriculture today can be understood as an enterprise to provide subsistence for those doing the work, staples for the community in which the food is grown and income from the sale of commodities to an external market. A staple food is one that supplies a major part of energy and nutrient needs and constitutes a dominant part of the diet. Excluding animal products, most people live off of one or two of the following staples: rice, wheat, maize (corn), millet, sorghum, and roots and tubers (potatoes, cassava, yams and taro). Although there are 50,000 edible plant species in the world, only 15 provide 90% of the world’s food energy intake.

Cereals constitute the principal commodity category that the world depends upon for its staples. Cereals include wheat and rice, the principal food staples, and coarse grains, which are used for animal feed. Three—rice, maize and wheat—are staples to more than 4.0 billion people. Rice feeds about half of the world’s population (Loftas 1995).

Another basic food crop is the starchy foods: cassava, sweet potatoes, potatoes, yams, taro and plantains. More than 1 billion people in developing nations use roots and tubers as staples. Cassava is grown as a staple in developing countries for 500 million people. For some of these commodities, much of the production and consumption remains at the subsistence level.

An additional basic food crop is the pulses, which comprise a number of dry beans—peas, chickpeas and lentils; all are legumes. They are important for their starch and protein.

Other legumes are used as oil crops; they include soybeans and groundnuts. Additional oil crops, used to make vegetable oil, include coconuts, sesame, cotton seed, oil palm and olive. In addition, some maize and rice bran are used to make vegetable oil. Oil crops also have uses other than for food, such as in manufacturing paints and detergents (Alexandratos 1995).

Small landholders grow many of the same crops as plantation operations do. Plantation crops, typically thought of as tropical export commodities, include natural rubber, palm oil, cane sugar, tropical beverages (coffee, cocoa, tea), cotton, tobacco and bananas. They may include crops that are also grown for both local consumption and export, such as coffee and sugar cane (ILO 1994).

Urban agriculture is labour intensive, occurs on small plots and is present in developed as well as developing countries. In the United States, more than one-third of the dollar value of agricultural crops is produced in urban areas and agriculture may employ as much as 10% of the urban population. In contrast, up to 80% of the population in smaller Siberian and Asian cities may be employed in agricultural production and processing. An urban farmer’s produce may also be used for barter, such as paying a landlord (UNDP 1996).

Characteristics of the Industry and Workforce

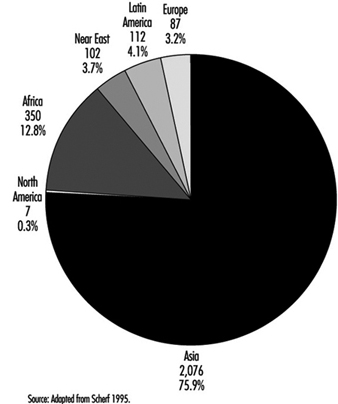

The 1994 world population totalled 5,623,500,000, and 2,735,021,000 (49%) of this population was engaged in agriculture, as shown in figure 1 . The largest component of this workforce is in the developing nations and transitional economies. Less than 100 million are in the developed nations, where mechanization has added to their productivity.

Figure 1. Millions of people engaged in agriculture by world region (1994)

Farming employs men and women, young and old. Their roles vary; for example, women in sub-Saharan Africa produce and market 90% of locally grown food. Women are also given the task of growing the subsistence diet for their families (Loftas 1995).

Children become farm labourers around the world at an early age (figure 2 ), working typically 45 hours per week during harvesting operations. Child labour has been a part of plantation agriculture throughout its history, and a prevalent use of contract labour based upon compensation for tasks completed aggravates the problem of child labour. Whole families work to increase the task completion in order to sustain or increase their income.

Figure 2. Young boy working in agriculture in India

Data on plantation employment generally show that the highest incidence of poverty is among agricultural wage labourers working in commercial agriculture. Plantations are located in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, and living and working conditions there may aggravate health problems that accompany the poverty (ILO 1994).

Agriculture in urban areas is another important component of the industry. An estimated 200 million farmers work part-time—equivalent to 150 million full-time workers—in urban agriculture to produce food and other agricultural products for the market. When subsistence agriculture in urban areas is included, the total reaches 800 million (UNDP 1996).

Total agricultural employment by major world region is shown in figure 1. In both the United States and Canada, a small proportion of the population is employed in agriculture, and farms are becoming fewer as operations consolidate. In Western Europe, agriculture has been characterized by smallholdings, a relic of equal division of the previous holding among the children. However, with the migration from agriculture, holdings in Europe have been increasing in size. Eastern Europe’s agriculture carries a history of socialized farming. The average farm size in the former USSR was more than 10,000 hectares, while in other Eastern European countries it was about one-third that size. This is changing as these countries move toward market economies. Many Asian countries have been modernizing their agricultural operations, with some countries achieving rice surpluses. More than 2 billion people remain engaged in agriculture in this region, and much of the increased production is attributed to high- production species of crops such as rice. Latin America is a diverse region where agriculture plays an important economic role. It has vast resources for agricultural use, which has been increasing, but at the expense of tropical forests. In both the Middle East and Africa, per capita food production has seen a decline. In the Middle East, the principal limiting factor on agriculture is the availability of water. In Africa, traditional farming depends upon small, 3- to 5-hectare plots, which are operated by women while the men are employed elsewhere, some in other countries to earn cash. Some countries are developing larger farming operations.

" DISCLAIMER: The ILO does not take responsibility for content presented on this web portal that is presented in any language other than English, which is the language used for the initial production and peer-review of original content. Certain statistics have not been updated since the production of the 4th edition of the Encyclopaedia (1998)."