Risk factors are genetic, physiological, behavioural and socioeconomic characteristics of individuals that place them in a cohort of the population that is more likely to develop a particular health problem or disease than the rest of the population. Usually applied to multifactorial diseases for which there is no single precise cause, they have been particularly useful in identifying candidates for primary preventive measures and in assessing the effectiveness of the prevention programme in controlling the risk factors being targeted. They owe their development to large-scale prospective population studies, such as the Framingham study of coronary artery disease and stroke conducted in Framingham, Massachusetts, in the United States, other epidemiological studies, intervention studies and experimental research.

It should be emphasized that risk factors are merely expressions of probability—that is, they are not absolute nor are they diagnostic. Having one or more risk factors for a particular disease does not necessarily mean that an individual will develop the disease, nor does it mean that an individual without any risk factors will escape the disease. Risk factors are individual characteristics which affect that person’s chances of developing a particular disease or group of diseases within a defined future time period. Categories of risk factors include:

- somatic factors, such as high blood pressure, lipid metabolism disorders, overweight and diabetes mellitus

- behavioural factors, such as smoking, poor nutrition, lack of physical movement, type-A personality, high alcohol consumption and drug abuse

- strains, including exposures in the occupational, social and private spheres.

Naturally, genetic and dispositional factors also play a role in high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus and lipid metabolism disorders. Many of the risk factors promote the development of arteriosclerosis, which is a significant precondition for the onset of coronary heart disease.

Some risk factors may put the individual at risk for the development of more than one disease; for example, cigarette smoking is associated with coronary artery disease, stroke and lung cancer. At the same time, an individual may have multiple risk factors for a particular disease; these may be additive but, more often, the combinations of risk factors may be multiplicative. Somatic and lifestyle factors have been identified as the main risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke.

Hypertension

Hypertension (increased blood pressure), a disease in its own right, is one of the major risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke. As defined by the WHO, blood pressure is normal when the diastolic is below 90 mm Hg and the systolic is below 140 mm Hg. In threshold or borderline hypertension, the diastolic ranges from 90 to 94 mm Hg and the systolic from 140 to 159 mm Hg. Individuals with diastolic pressures equal to or greater than 95 mm Hg and systolic pressures equal to or greater than 160 mm Hg are designated as being hypertensive. Studies have shown, however, that such sharp criteria are not entirely correct. Some individuals have a “labile” blood pressure—the pressure fluctuates between normal and hypertensive levels depending on the circumstances of the moment. Further, without regard to the specific categories, there is a linear progression of relative risk as the pressure rises above the normal level.

In the United States, for example, the incidence rate of CHD and stroke among men aged 55 to 61 was 1.61% per year for those whose blood pressure was normal compared to 4.6% per year for those with hypertension (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 1981).

Diastolic pressures over 94 mm Hg were found in 2 to 36% of the population aged 35 to 64 years, according to the WHO-MONICA study. In many countries of Central, Northern and Eastern Europe (e.g., Russia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Scotland, Romania, France and parts of Germany, as well as Malta), hypertension was found in over 30% of the population aged 35 to 54, while in countries including Spain, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, Canada and the United States, the corresponding figure was less than 20% (WHO-MONICA 1988). The rates tend to increase with age, and there are racial differences. (In the United States, at least, hypertension is more frequent among African-Americans than in the White population.)

Risks for developing hypertension

The important risk factors for developing hypertension are excess body weight, high salt intake, a series of other nutritional factors, high alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and psychosocial factors, including stress (Levi 1983). Furthermore, there is a certain genetic component whose relative significance is not yet fully understood (WHO 1985). Frequent familial high blood pressure should be considered a danger and special attention paid to controlling lifestyle factors.

There is evidence that psychosocial and psychophysical factors, in conjunction with the job, can have an influence on developing hypertension, especially for short-term blood pressure increases. Increases have been found in the concentration of certain hormones (adrenalin and noradrenalin) as well as cortisol (Levi 1972), which, alone and in combination with high salt consumption, can lead to increased blood pressure. Work stress also appears to be related to hypertension. A dose-effect relationship with intensity of air traffic was shown (Levi 1972; WHO 1985) in comparing groups of air traffic controllers with different high psychic strain.

Treatment of hypertension

Hypertension can and should be treated, even in the absence of any symptoms. Lifestyle changes such as weight control, reduction of sodium intake and regular physical exercise, coupled when necessary with anti-hypertensive medications, regularly evoke re- ductions in blood pressure, often to normal levels. Unfortunately, many individuals found to be hypertensive are not receiving adequate treatment. According to the WHO-MONICA study (1988), less than 20% of hypertensive women in Russia, Malta, eastern Germany, Scotland, Finland and Italy were receiving adequate treatment during the mid-1980s, while the comparable figure for men in Ireland, Germany, China, Russia, Malta, Finland, Poland, France and Italy was under 15%.

Prevention of hypertension

The essence of preventing hypertension is identifying individuals with blood pressure elevation through periodic screening or medical examination programmes, repeated checks to verify the extent and duration of the elevation, and the institution of an appropriate treatment regimen that will be maintained indefinitely. Those with a family history of hypertension should have their pressures checked more frequently and should be guided to elimination or control of any risk factors they may present. Control of alcohol abuse, physical training and physical fitness, normal weight maintenance and efforts to reduce psychological stress are all important elements of prevention programmes. Improvement in workplace conditions, such as reducing noise and excess heat, are other preventive measures.

The workplace is a uniquely advantageous arena for programmes aimed at the detection, monitoring and control of hypertension in the workforce. Convenience and low or no cost make them attractive to the participants and the positive effects of peer pressure from co-workers tend to enhance their compliance and the success of the programme.

Hyperlipidemia

Many long-term international studies have demonstrated a convincing relationship between abnormalities in lipid metabolism and an increased risk of CHD and stroke. This is particularly true for elevated total cholesterol and LDL (low density lipoproteins) and/or low levels of HDL (high density lipoproteins). Recent research provides further evidence linking the excess risk with different lipoprotein fractions (WHO 1994a).

The frequency of elevated total cholesterol levels >>6.5 mmol/l) was shown to vary considerably in population groups by the worldwide WHO-MONICA studies in the mid-1980s (WHO- MONICA 1988). The rate of hypercholesterolemia for popu- lations of working age (35 to 64 years of age) ranged from 1.3 to 46.5% for men and 1.7 to 48.7% for women. Although the ranges were generally similar, the mean cholesterol levels for the study groups in different countries varied significantly: in Finland, Scot- land, East Germany, the Benelux countries and Malta, a mean of over 6 mmol/l was found, while the means were lower in east Asian countries like China (4.1 mmol/l) and Japan (5.0 mmol/l). In both regions, the means were below 6.5 mmol/l (250 mg/dl), the level designated as the threshold of normal; however, as noted above for blood pressure, there is a progressive increase of risk as the level rises, rather than a sharp demarcation between normal and abnormal. Indeed, some authorities have pegged a total chol- esterol level of 180 mg/dl as the optimal level that should not be exceeded.

It should be noted that gender is a factor, with women averaging lower levels of HDL. This may be one reason why women of working age have a lower mortality rate from CHD.

Except for the relatively few individuals with hereditary hyper- cholesterolemia, cholesterol levels generally reflect the dietary intake of foods rich in cholesterol and saturated fats. Diets based on fruit, plant products and fish, with reduced total fat intake and substitution of poly-unsaturated fats, are generally associated with low cholesterol levels. Although their role is not yet entirely clear, intake of anti-oxidants (vitamin E, carotene, selenium and so on) is also thought to influence cholesterol levels.

Factors associated with higher levels of HDL cholesterol, the “protective” form of lipoprotein, include race (Black), gender (female), normal weight, physical exercise and moderate alcohol intake.

Socio-economic level also appears to play a role, at least in industrialized countries, as in West Germany, where higher cholesterol levels were found in population groups of both men and women with lower education levels (under ten years of schooling) compared to those completing 12 years of education (Heinemann 1993).

Cigarette Smoking

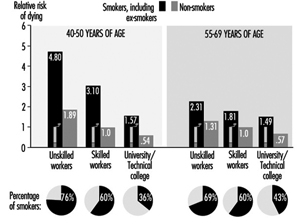

Cigarette smoking is among the most important risk factors for CVD. The risk from cigarette smoking is directly related to the number of cigarettes one smokes, the length of time one has been smoking, the age at which one began to smoke, the amount one inhales and the tar, nicotine and carbon monoxide content of the inspired smoke. Figure 1 illustrates the striking increase in CHD mortality among cigarette smokers compared to non-smokers. This increased risk is demonstrated among both men and women and in all socio-economic classes.

The relative risk of cigarette smoking declines after tobacco use is discontinued. This is progressive; after about ten years of non-smoking, the risk is down almost to the level of those who never smoked.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that those inhaling “second-hand smoke” (i.e., passive inhalation of smoke from cigarettes smoked by others) are also at significant risk (Wells 1994; Glantz and Parmley 1995).

Rates of cigarette smoking vary among countries, as demonstrated by the international WHO-MONICA study (1988). The highest rates for men aged 35 to 64 were found in Russia, Poland, Scotland, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Japan and China. More women smokers were found in Scotland, Denmark, Ireland, the United States, Hungary and Poland (the recent Polish data are limited to large cities).

Social status and occupational level are factors in the level of smoking among workers. Figure 1, for example, demonstrates that the proportions of smokers among men in East Germany increased in the lower social classes. The reverse is found in countries with relatively low numbers of smokers, where there is more smoking among those at higher social levels. In East Germany, smoking is also more frequent among shift-workers when compared with those on a “normal” work schedule.

Figure 1. Relative mortality risk from cardiovascular diseases for smokers (including ex-smokers) and social classes compared to non-smoking, normal weight, skilled workers (male) based on occupational medical care examinations in East Germany, mortality 1985-89, N= 2.7 million person years.

Unbalanced Nutrition, Salt Consumption

In most industrialized countries traditional low-fat nutrition has been replaced by high-calorie, high-fat, low carbohydrate, too sweet or too salty eating habits. This contributes to the development of overweight, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol level as elements of high cardiovascular risk. The heavy consumption of animal fats, with their high proportion of saturated fatty acids, leads to an increase in LDL cholesterol and increased risk. Fats derived from vegetables are much lower in these substances (WHO 1994a). Eating habits are also strongly associated with both socio-economic level and occupation.

Overweight

Overweight (excess fat or obesity rather than increased muscle mass) is a cardiovascular risk factor of lesser direct significance. There is evidence that the male pattern of excess fat distribution (abdominal obesity) is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular and metabolic problems than the female (pelvic) type of fat distribution.

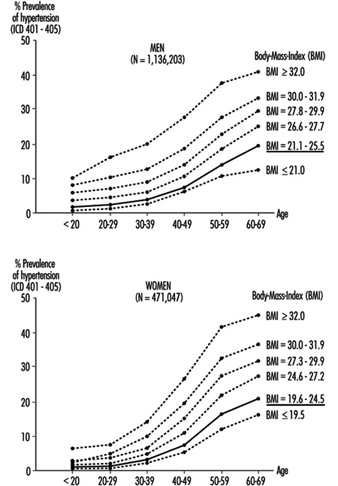

Overweight is associated with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes mellitus, and, to a much greater extent in women than men, tends to increase with age (Heuchert and Enderlein 1994) (Figure 2). It is also a risk factor for musculoskeletal problems and osteoarthritis, and makes physical exercise more difficult. The frequency of significant overweight varies considerably among countries. Random population surveys conducted by the WHO-MONICA project found it in more than 20% of females aged 35 to 64 in the Czech Republic, East Germany, Finland, France, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Spain and Yugoslavia, and in both sexes in Lithuania, Malta and Romania. In China, Japan, New Zealand and Sweden, fewer than 10% of both men and women in this age group were significantly overweight.

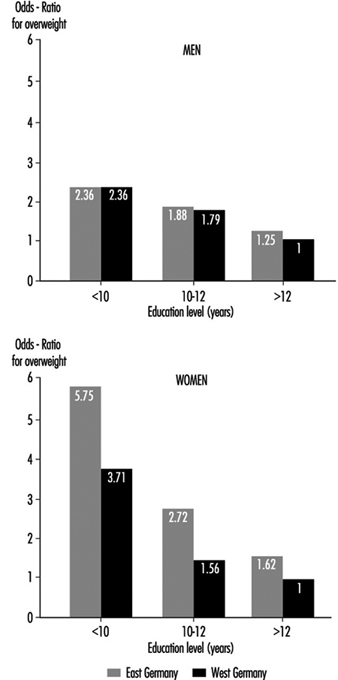

Common causes of overweight include familial factors (these may in part be genetic but more often reflect common dietary habits), overeating, high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets and lack of physical exercise. Overweight tends to be more common among the lower socio-economic strata, particularly among women, where, among other factors, financial constraints limit the availability of a more balanced diet. Population studies in Germany demonstrated that the proportion of significant overweight among those with lower education levels is 3 to 5 times greater than that among people with more education, and that some occupations, notably food preparation, agriculture and to some extent shift work, have a high percentage of overweight people (Figure 3) (Heinemann 1993).

Figure 2. Prevalence of hypertension by age, sex and six levels of relative body weight according tot he body-mass index (BMI) in occupational medical care examinations in East Germany (normal BMI values are underlined).

Figure 3. Relative risk from overweight by length of education(years of schooling) in Germay (population 25-64 years).

Physical Inactivity

The close association of hypertension, overweight and diabetes mellitus with lack of exercise at work and/or off the job has made physical inactivity a significant risk factor for CHD and stroke (Briazgounov 1988; WHO 1994a). A number of studies have demonstrated that, holding all other risk factors constant, there was a lower mortality rate among persons engaging regularly in high-intensity exercises than among those with a sedentary lifestyle.

The amount of exercise is readily measured by noting its duration and either the amount of physical work accomplished or the extent of the exercise-induced increase in heart rate and the time required for that rate to return to its resting level. The latter is also useful as an indicator of the level of cardiovascular fitness: with regular physical training, there will be less of an increase in heart rate and a more rapid return to the resting rate for a given intensity of exercise.

Workplace physical fitness programmes have been shown to be effective in enhancing cardiovascular fitness. Participants in these tend also to give up cigarette smoking and to pay greater attention to proper diets, thus significantly reducing their risk of CHD and stroke.

Alcohol

High alcohol consumption, especially the drinking of high-proof spirits, has been associated with a greater risk of hypertension, stroke and myocardiopathy, while moderate alcohol use, particularly of wine, has been found to reduce the risk of CHD (WHO 1994a). This has been associated with the lower CHD mortality among the upper social strata in industrialized countries, who generally prefer wine to “hard” liquors. It should also be noted that while their alcohol intake may be similar to that of wine drinkers, beer drinkers tend to accumulate excess weight, which, as noted above, may increase their risk.

Socio-economic Factors

A strong correlation between socio-economic status and the risk of CVD has been demonstrated by analyses of the death register mortality studies in Britain, Scandinavia, Western Europe, the United States and Japan. For example, in eastern Germany, the cardiovascular death rate is considerably lower for the upper social classes than for the lower classes (see Figure 1) (Marmot and Theorell 1991). In England and Wales, where general mortality rates are declining, the relative gap between the upper and lower classes is widening.

Socio-economic status is typically defined by such indicators as occupation, occupational qualifications and position, level of education and, in some instances, income level. These are readily translated into standard of living, nutritional patterns, free-time activities, family size and access to medical care. As noted above, behavioural risk factors (such as smoking and diet) and the somatic risk factors (such as overweight, hypertension and hyperlipidemia) vary considerably among social classes and occupational groups (Mielck 1994; Helmert, Shea and Maschewsky Schneider 1995).

Occupational Psychosocial Factors and Stress

Occupational stress

Psychosocial factors at the workplace primarily refer to the combined effect of working environment, work content, work demands and technological-organizational conditions, and also to personal factors like capability, psychological sensitivity, and finally also to health indicators (Karasek and Theorell 1990; Siegrist 1995).

The role of acute stress on people who already suffer from cardiovascular disease is uncontested. Stress leads to episodes of angina pectoris, rhythm disorders and heart failure; it can also precipitate a stroke and/or a heart attack. In this context stress is generally understood to mean acute physical stress. But evidence has been mounting that acute psychosocial stress can also have these effects. Studies from the 1950s showed that people who work two jobs at a time, or who work overtime for long periods, have a relatively higher risk of heart attack, even at a young age. Other studies showed that in the same job, the person with the greater work and time pressure and frequent problems on the job is at significantly greater risk (Mielck 1994).

In the last 15 years, job stress research suggests a causal relationship between work stress and the incidence of cardiovascular disease. This is true for cardiovascular mortality as well as frequency of coronary disease and hypertension (Schnall, Landsbergis and Baker 1994). Karasek’s job strain model defined two factors that could lead to an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease:

- extent of job demands

- extent of decision-making latitude.

Later Johnson added as a third factor the extent of social support (Kristensen 1995) which is discussed more fully elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia. The chapter Psychosocial and Organizational Factors includes discussions on individual factors, such as Type A personality, as well as social support and other mechan- isms for overcoming the effects of stress.

The effects of factors, whether individual or situational, that lead to increased risk of cardiovascular disease can be reduced by “coping mechanisms”, that is, by recognizing the problem and overcoming it by attempting to make the best of the situation.

Until now, measures aimed at the individual have predominated in the prevention of the negative health effects of work stress. Increasingly, improvements in organizing the work and expanding employee decision-making latitude have been used (e.g., action research and collective bargaining; in Germany, occupational quality and health circles) to achieve an improvement in productivity as well as to humanize the work by decreasing the stress load (Landsbergis et al. 1993).

Night and Shift Work

Numerous publications in the international literature cover the health risks posed by night and shift work. It is generally accepted that shift work is one risk factor which, together with other relev- ant (including indirect) work-related demands and expectation factors, leads to adverse effects.

In the last decade research on shift work has increasingly dealt with the long-term effects of night and shift work on the frequency of cardiovascular disease, especially ischaemic heart disease and myocardial infarction, as well as cardiovascular risk factors. The results of epidemiological studies, especially from Scandinavia, permit a higher risk of ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction to be presumed for shift workers (Alfredsson, Karasek and Theorell 1982; Alfredsson, Spetz and Theorell 1985; Knutsson et al. 1986; Tüchsen 1993). In Denmark it was even estimated that 7% of cardiovascular disease in men as well as women can be traced to shift work (Olsen and Kristensen 1991).

The hypothesis that night and shift workers have a higher risk (estimated relative risk approximately 1.4) for cardiovascular disease is supported by other studies that consider cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension or fatty acid levels for shift workers as compared to day workers. Various studies have shown that night and shift work may induce increased blood pressure and hypertension as well as increased triglyceride and/or serum cholesterol (as well as normal range fluctuations for HDL-cholesterol in increased total cholesterol). These changes, together with other risk factors (like heavy cigarette smoking and overweight among shift workers), can cause increased morbidity and mortality due to atherosclerotic disease (DeBacker et al. 1984; DeBacker et al. 1987; Härenstam et al. 1987; Knutsson 1989; Lavie et al. 1989; Lennernäs, Åkerstedt and Hambraeus 1994; Orth-Gomer 1983; Romon et al. 1992).

In all, the question of possible causal links between shift work and atherosclerosis cannot be definitively answered at present, as the pathomechanism is not sufficiently clear. Possible mechanisms discussed in the literature include changes in nutrition and smoking habits, poor sleep quality, increases in lipid level, chronic stress from social and psychological demands and disrupted circadian rhythms. Knutsson (1989) has proposed an interesting pathogenesis for the long-term effects of shift work on chronic morbidity.

The effects of various associated attributes on risk estimation have hardly been studied, since in the occupational field other stress-inducing working conditions (noise, chemical hazardous materials, psychosocial stress, monotony and so on) are connected with shift work. From the observation that unhealthy nutritional and smoking habits are often connected with shift work, it is often concluded that an increased risk of cardiovascular disease among shift workers is more the indirect result of unhealthy behaviour (smoking, poor nutrition and so on) than directly the result of night or shift work (Rutenfranz, Knauth and Angersbach 1981). Furthermore, the obvious hypothesis of whether shift work promotes this conduct or whether the difference comes primarily from the choice of workplace and occupation must be tested. But regardless of the unanswered questions, special attention must be paid in cardiovascular prevention programmes to night and shift workers as a risk group.

Summary

In summary, risk factors represent a broad variety of genetic, somatic, physiological, behavioural and psychosocial characteristics which can be assessed individually for individuals and for groups of individuals. In the aggregate, they reflect the probability that CVD, or more precisely in the context of this article, CHD or stroke will develop. In addition to elucidating the causes and pathogenesis of multifactorial diseases, their chief importance is that they delineate individuals who should be targets for risk factor elimination or control, an exercise admirably suited to the workplace, while repeated risk assessments over time demonstrate the success of that preventive effort.