Occupational stigma or occupational marks are work-induced anatomical lesions which do not impair working capacity. Stigmata are generally caused by mechanical, chemical or thermal skin irritation over a long period and are often characteristic of a particular occupation. Any kind of pressure or friction on the skin may produce an irritating effect, and a single violent pressure may break the epidermis, leading to the formation of excoriations, seropurulent blisters and infection of the skin and underlying tissues. On the other hand, however, frequent repetition of moderate irritant action does not disrupt the skin but stimulates defensive reactions (thickening and keratinization of the epidermis). The process may take three forms:

- a diffuse thickening of the epidermis which merges into the normal skin, with preservation and occasional accentuation of skin ridges and unimpaired sensitivity

- a circumscribed callosity made up of smooth, elevated, yellowish, horny lamellae, with partial or complete loss of skin ridges and impairment of sensitivity. The lamellae are not circumscribed; they are thicker in the centre and thinner towards the periphery and blend into the normal skin

- a circumscribed callosity, mostly raised above the normal skin, 15 mm in diameter, yellowish-brown to black in colour, painless and occasionally associated with hypersecretion of the sweat glands.

Callosities are usually produced by mechanical agents, sometimes with the aid of a thermal irritant (as in the case of glass- blowers, bakers, firefighters, meat curers, etc.), when they are dark-brown to black in colour with painful fissures. If, however, the mechanical or thermal agent is combined with a chemical irritant, callosities undergo discoloration, softening and ulceration.

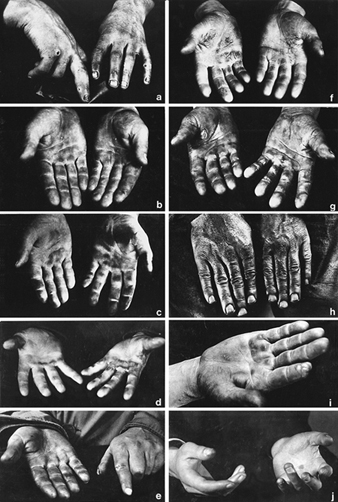

Callosities which represent a characteristic occupational reaction (particularly on the skin of the hand as shown in figure 1 and 2) are seen in many occupations. Their form and localization are determined by the site, force, manner and frequency of the pressure exerted, as well as by the tools or materials used. The size of callosities may also reveal a congenital tendency to skin keratinization (ichthyosis, hereditary keratosis palmaris). These factors may also often be decisive as concerns deviations in the localization and size of callosities in manual workers.

Figure 1. Occupational stigmata on the hands.

(a) Tanner’s ulcers; (b) Blacksmith; (c) Sawmill worker; (d) Stonemason; (e) Mason; (f) Marble Mason; (g) Chemical factory worker; (h) Paraffin refinery worker; (I) Printer; (j) Violinist

(Photos: Janina Mierzecka.)

Figure 2. Calluses at pressure points on the palm of the hand.

Callosities normally act as protective mechanisms but may, under certain conditions, acquire pathological features; for this reason they should not be overlooked when pathogenesis and, particularly, prophylaxis of occupational dermatoses are envisaged.

When a worker gives up a callosity-inducing job, the superfluous horny layers undergo exfoliation, the skin becomes thin and soft, the discoloration disappears and the normal appearance is restored. The time required for skin regeneration varies: occupational callosities on the hands may occasionally be seen several months or years after the work has been given up (especially in blacksmiths, glass-blowers and sawmill workers). They persist longer in senile skin and when associated with connective tissue degeneration and bursitis.

Fissures and erosions of the skin are characteristic of certain occupations (railway workers, gunsmiths, bricklayers, goldsmiths, basket weavers, etc.). The painful “tanner’s ulcer” associated with chromium compound exposures (figure 1) round or oval in shape and from 2-10 mm in diameter. The localisation of occupational lesions (e.g. on confectioners’ fingers, tailors’ fingers and palms, etc.) is also characteristic.

Pigment spots are caused by the absorption of dyes through the skin, the penetration of particles of solid chemical compounds or industrial metals, or the excessive accumulation of the skin pigment, melanin, in workers in coking or generator plants, after three to five years of work. In some establishments, about 32% of workers were found to exhibit melanomata. Pigment spots are mostly found in chemical workers.

As a rule, dyes absorbed through the skin cannot be removed by routine washing, hence their permanence and significance as occupational stigmata. Pigment spots occasionally result from impregnation with chemical compounds, plants, soil or other substances to which the skin is exposed during the work process.

A number of occupational stigmata may be seen in the region of the mouth (e.g. Burton’s line within the gums of workers exposed to lead, teeth erosion in workers exposed to acid fumes, etc. blue colouring of the lips in workers engaged in aniline manufacture and in the form of acne. Characteristic odours connected with certain occupations may also be considered as occupational stigmata.