Every employer is contractually obligated to take precautions to guarantee the safety of his employees. The labour-related rules and regulations to which attention must be paid are of necessity just as various as the dangers present in the workplace. For this reason, the Occupational Safety Act (ASiG) of the Federal Republic of Germany includes among the duties of employers a legal obligation to consult specialist professionals on matters of occupational safety. This means that the employer is required to appoint not only specialist staff (particularly for technical solutions) but also company doctors for medical aspects of occupational safety.

The Occupational Safety Act has been in effect since December 1973. There were in the FRG at that time only about 500 doctors trained in what was called occupational medicine. The system of statutory accident insurance has played a decisive role in the development and construction of the present system, by means of which occupational medicine has established itself in companies in the persons of company doctors.

Dual Occupational Health and Safety System in the Federal Republic of Germany

As one of five branches of social insurance, the statutory accident insurance system makes a priority the task of taking all appropriate measures to ensure prevention of work accidents and occupational diseases through detection and elimination of work-related health hazards. In order to fulfil this legal mandate, legislators have granted extensive authority to a self-governing accident insurance system to enact its own rules and regulations concretizing and shaping the requisite preventive precautions. For this reason, the statutory accident insurance system has—within the bounds of existing public law—taken over the role of determining when an employer is required to take on a company doctor, what expert qualifications in occupational medicine the employer may demand of the company doctor and how much time the employer may estimate that the doctor will have to spend on the care of his employees.

The first draft of this accident prevention regulation dates from 1978. At that time, the number of available doctors with expertise in occupational medicine did not appear sufficient to provide all businesses with the care of company doctors. Thus the decision was made at first to establish concrete conditions for the larger businesses. At that time, to be sure, the businesses belonging to large-scale industry had often already made their own arrangements for company doctors, arrangements which already met or even exceeded the requirements stated in the accident prevention regulations.

Employment of a Company Doctor

The hours allocated in firms for the care of employees—called assignment times—are established by the statutory accident insurance system. Knowledge available to insurers concerning the existing risks to health in the various branches formed the basis for the calculation of the assignment times. The classification of firms with regard to particular insurers and the evaluation of possible health risks undertaken by them were thus the basis for the assignment of a company doctor.

Since the care rendered by company doctors is an occupational safety measure, the employer must cover the costs of assignment for such doctors. The number of employees within each of the several areas of hazard multiplied by the time allocated for care determine the sum of financial expenses. The result is a range of different forms of care, since it can pay—depending on the size of a firm—either to employ a doctor or doctors full-time, that is as the company’s own, or part-time, with services rendered on an hourly basis. This variety of requirements has led to a variety of organizational forms in which occupational medical services are offered.

The Duties of a Company Doctor

In principle, a distinction should be made, for legal reasons, between the provisions made by companies to provide care for employees and the work done by the doctors in the public health system responsible for the general medical care of the population.

In order to differentiate clearly which services of occupational medicine employers are responsible for, which are given in figure 1, the Occupational Safety Act has already anchored in law a catalogue of duties for company doctors. The company doctor is not subject to the orders of the employer in the fulfilment of these tasks; still, company doctors have had to fight the image of an employer-appointed doctor up to the present day.

Figure 1. The duties of occupational physicians employed by companies in Germany

One of the essential duties of the company doctor is the occupational medical examination of employees. This examination can become necessary according to the specific features of a given concern, if particular working conditions exist which lead the company doctor to offer, of his own accord, an examination to the employees involved. He cannot, however, force an employee to allow himself to be examined by him, but must rather convince him through trust.

Special Preventive Checkups in Occupational Medicine

There exists, in addition to this kind of examination, the special preventive check-up, participation in which by the employee is expected by the employer on legal grounds. These special preventive checkups end in the issuance of a doctor’s certificate, in which the examining doctor certifies that, based on the examination conducted, he has no objection to the employee’s engaging in work at the workplace in question. The employer may assign the employee only once for each certificate issued.

Special preventive checkups in occupational medicine are legally prescribed if exposure to particular hazardous materials occurs in the workplace or if particular hazardous activities belong to job practice and such health risks cannot be excluded through appropriate occupational safety precautions. Only in exceptional circumstances—as is the case, for example, with radiation protection checkups—is the legal requirement that an examination be performed supplemented by legal regulations concerning what the doctor carrying out the examination must pay attention to, which methods he must apply, which criteria he must use to interpret the outcome of the examination and which criteria he must apply in judging health status with regard to work assignments.

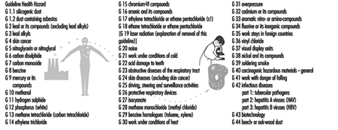

This is why in 1972 the Berufsgenossenschaften, made up of commercial trade associations which provide the accident insurance for trade and industry, authorized a committee of experts to work out commensurate recommendations to doctors working in occupational medicine. Such recommendations have existed for more than 20 years. The Berufsgenossenschaften Guidelines for Special Preventive Checkups, listed in figure 2, now show a total of 43 examination procedures for the various health hazards which can be countered, on the grounds of present knowledge, with appropriate medical precautionary measures so as to prevent diseases from developing.

Figure 2. A summary information on external services of the Berufgenossenschaften in the German building industry

The Berufsgenossenschaften deduce the mandate to make available such recommendations from their duty to take all appropriate measures to prevent occupational diseases from arising. These Guidelines for Special Preventive Checkups are a standard work in the field of occupational medicine. They find application in all spheres of activity, not only in enterprises in the sphere of trade and industry.

In connection with the provision of such occupational medical recommendations, the Berufsgenossenschaften also took steps early on to ensure that in businesses lacking their own company doctor the employer would be required to arrange for these preventive checkups. Subject to certain basic requirements having to do primarily with the specialized knowledge of the doctor, but also with the facilities available in his or her practice, even doctors without expertise in occupational medicine can acquire the authority to offer companies their services in performing preventive checkups, contingent on a policy administered by the Berufsgenossenschaften. This was the precondition for the current availability of the total of 13,000 authorized doctors in Germany who perform the 3.8 million preventive checkups performed annually.

It was the supply of a sufficient number of doctors that also made it possible legally to require that employers initiate these special preventive checkups in complete independence of the question of whether or not the company employs a doctor prepared to do such checkups. In this way, it became possible to use the statutory accident insurance system to ensure enforcement of certain measures of health protection at work, even at the level of small businesses. The relevant legal regulations may be found in the Ordinance on Hazardous Substances and, comprehensively, in the accident prevention regulation, which regulates the rights and duties of the employer and the examined employee and the function of the licensed doctor.

Care Provided by Company Doctors

The statistics released annually by the Federal Board of Doctors (Bundesärztekammer) show that for the year 1994 more than 11,500 doctors fulfil the prerequisites, in the form of specialist knowledge in industrial medicine, to be company doctors (see table 1). In the Federal Republic of Germany, the organization Standesvertretung representing the medical profession regulates autonomously which qualifications must be met by doctors as regards study and subsequent professional development before they may become active as doctors in a given field of medicine.

Table 1. Doctors with specialist knowledge in occupational medicine

|

Number* |

Percentage* |

|

|

Field designation “occupational medicine” |

3,776 |

31.4 |

|

Additional designation “corporate medicine” |

5,732 |

47.6 |

|

Specialist knowledge in occupational medicine |

2,526 |

21.0 |

|

Total |

12,034 |

100 |

* As of 31 December 1995.

The satisfaction of these prerequisites for the activity of a company doctor represents either the attainment of the field designation “occupational medicine” or of the additional designation “corporate medicine”—that is, either four years’ further study after the licence to practice in order to be active exclusively as a work physician, or three years’ further study, after which activity as a company doctor is allowed only in so far as it is connected with medical activity in another field (e.g., as an internist). Doctors tend to prefer the second variant. This means, however, that they themselves see the chief emphasis of their professional work as physicians in a classical field of medical activity, not in occupational medical practice.

For these doctors, occupational medicine has the significance of an auxiliary source of income. This explains at the same time why the medical element of the examination by doctors continues to dominate the practical exercise of the profession of company doctor, although the legislature and the statutory accident insurance system themselves emphasize inspection of companies and medical advice given to employers and employees.

In addition, there still exists a group of doctors who, having acquired specialist knowledge in occupational medicine in earlier years, met different requirements at that time. Of particular significance in this regard are the standards which doctors in the former German Democratic Republic were required to meet in order to be allowed to practice as company doctors.

Organization of Care Provided by Company Doctors

In principle, it is left up to the employer to choose freely a company doctor for the firm from among those offering occupational medical services. Since this supply was not yet available subsequent to the establishment, in the early 1970s, of the relevant legal preconditions, the statutory accident insurance system took the initiative in regulating the market economy of supply and demand.

The Berufsgenossenschaften of the building industry instituted their own occupational medical services by engaging doctors with specialist knowledge in occupational medicine in contracts to provide care, as company doctors, to the firms affiliated with them. Via their statutes, the Berufsgenossenschaften arranged for each of their firms to be cared for by its own occupational medical service. The costs incurred were distributed among all the firms through appropriate forms of financing. A summary of information concerning external occupational medical services of the Berufsgenossenschaften of the building industry is given in table 2.

Table 2. Company medical care provided by external occupational medical services,1994

|

Doctors providing care as primary occupation |

Doctors providing care as secondary occupation |

Centres |

Employees cared for |

|

|

ARGE Bau1 |

221 |

83 mobile: 46 |

||

|

BAD2 |

485 |

72 |

175 mobile: 7 |

1.64 million |

|

IAS3 |

183 |

58 |

500,000 |

|

|

TÜV4 |

72 |

|||

|

AMD Würzburg5 |

60–70 |

30–35 |

1 ARGE Bau = Workers’ Community of the Berufgenossenschaften of Building Industry Trade Associations.

2 BAD = Occupational Medical Service of the Berufgenossenschaften.

3 IAS = Institute for Occupational and Social Medicine.

4 TÜV = Technical Control Association.

5 AMD Würzburg = Occupational Medical Service of the Berufgenossenschaften.

The Berufsgenossenschaften for the maritime industry and that for domestic shipping also founded their own occupational medical services for their businesses. It is a characteristic of all of them that the idiosyncrasies of the businesses in their trade—non-stationary enterprises with special vocational requirements—were a decisive factor in their taking the initiative to make clear to their companies the necessity for company doctors.

Similar considerations occasioned the remaining Berufsgenossenschaften to unite themselves in a confederation in order to found the Occupational Medical Service of the Berufsgenossenschaften (BAD). This service organization, which offers its services to every enterprise in the market, was enabled at an early stage by the financial collateral provided by the Berufsgenossenschaften to be present over the entire area of the Federal Republic of Germany. Its broad coverage, as far as representation goes, was meant to ensure that even those businesses located in the Federal states, or states of relatively poor economic activity, of the Federal Republic would have access to a company doctor in their area. This principle has been maintained up to the present time. The BAD is considered, meanwhile, the largest provider of occupational medical services. Nonetheless, it is forced by the market economy to assert itself against competition from other providers, particularly within urban agglomerations, by maintaining a high level of quality in what it provides.

The occupational medical services of the Technical Control Association (TÜV) and of the Institute for Occupational and Social Medicine (IAS) are the second- and third-largest transregional providers. There are in addition numerous smaller, regionally active enterprises in all of the Federated States of Germany.

Cooperation with Other Providers of Services in Occupational Health and Safety

The Occupational Safety Act, as a legal foundation for care provided to companies by company doctors, provides also for professional supervision of occupational safety, particularly in order to ensure that aspects of occupational safety be handled by personnel schooled in technical precautions. The requirements of industrial practice have changed meanwhile to such an extent that technical knowledge regarding questions of occupational safety must now be supplemented more and more by familiarity with questions of the toxicology of materials used. In addition, questions of ergonomic organization of work conditions and of the physiological effects of biological agents play an increasing role in evaluations of stresses in a place of work.

The requisite knowledge may be mustered only through interdisciplinary cooperation of experts in the field of health and safety at work. Therefore, the statutory accident insurance system supports particularly the development of forms of organization which take such interdisciplinary cooperation into account at the organizational stage, and creates within its own structure the preconditions for this cooperation by redesigning its administrative departments in a suitable fashion. What was once called the Technical Inspection Service of the statutory accident insurance system turns into a field of prevention, within which not only technical engineers but also chemists, biologists and, increasingly, physicians are active together in designing solutions for problems of labour safety.

This is one of the indispensable prerequisites for creating a basis for the type of organization of interdisciplinary cooperation—within businesses and between safety technology service organizations and company doctors—required for efficient solution of the immediate problems of occupational health and safety.

In addition, supervision in respect of safety technology should be advanced, in all companies, just as much as supervision by company doctors. Safety specialists are to be employed by businesses on the same legal basis—the Occupational Safety Act—or appropriately trained personnel affiliated with the industry are to be supplied by the businesses themselves. Just as in the case of the supervision provided by company doctors, the accident prevention regulation, Specialists for Occupational Safety (VBG 122), has formulated the requirements according to which businesses must employ safety specialists. In the case of safety-technical supervision of businesses as well, these requirements take all necessary precautions to incorporate each of the 2.6 million firms currently comprising the commercial economy as well as those in the public sector.

Around two million of these firms have fewer than 20 employees and are classed as small industry. With the full supervision of all enterprises, that is, including the smaller and smallest of businesses, the statutory accident insurance system creates for itself a platform for the establishment of occupational health and safety in all areas.