Small workplaces have been a characteristic mode of production since earliest times. Cottage industries where members of a family work on the basis of a division of labour still exist in both urban and rural situations to this day. In fact, it is true of all countries that the majority of workers, paid or unpaid, work in enterprises which can be classified as small.

Before defining their health problems, it is necessary to define a small enterprise. It is generally recognized that a small enterprise is one employing 50 or fewer workers. It may be located in the home, a farm, a small office, a factory, mine or quarry, a forestry operation, a garden or a fishing boat. The definition is based on the number of workers, not what they do or whether they are paid or unpaid. The home is clearly a small enterprise.

Common Features of Small Enterprises

Common features of small enterprises include (see table 1):

- They are likely to be undercapitalized.

- They are usually non-unionized (the home and the farm in particular) or under-unionized (office, factory, food shop, etc.).

- They are less likely to be inspected by government agencies. In fact, a study carried out some years ago indicated that the existence of many small enterprises was not even known to the government department responsible for them (Department of Community Health 1980).

Table 1. Features of small-scale enterprises and their consequences

Lack of capital

- poor environmental conditions

- cheaper raw materials

- inferior equipment maintenance

- inadequate personal protection

Non- or under-unionization

- inferior pay rates

- longer working hours

- non-compliance with award conditions

- exploitation of child labour

Inferior inspection services

- poor environmental conditions

- greater hazard level

- higher injury/illness rates

As a result, workplace environmental conditions, which generally reflect available capital, are inevitably inferior to those in larger enterprises: cheaper raw materials will be purchased, maintenance of machinery will be reduced and personal protective equipment will be less available.

Under- or non-unionization will lead to inferior pay rates, longer working hours and non-compliance with award conditions. Work will often be more intensive and children and old people are more likely to be exploited.

Inferior inspection services will result in poorer working environments, more workplace hazards and higher injury and illness rates.

These characteristics of small enterprises place them at the edge of economic survival. They come into and go out of existence on a regular basis.

To balance these significant disadvantages, small enterprises are flexible in their productive systems. They can respond quickly to change and often develop imaginative and flexible solutions to the requirements of technical challenge. At a social level, the owner is usually a working manager and interacts with the workers on a more personal level.

There is evidence to support these beliefs. For example, one US study found that the workers in neighbourhood panel beating shops were regularly exposed to solvents, metal pigments, paints, polyester plastic fumes and dust, noise and vibration (Jaycock and Levin 1984). Another US survey showed that multiple short-term exposures to chemical substances were characteristic of small industries (Kendrick, Discher and Holaday 1968).

A Finnish study investigating this occurrence in 100 workplaces found that short-duration exposures to chemicals were typical in small industry and that the duration of exposure increased as the firm grew (Vihina and Nurminen 1983). Associated with this pattern were multiple exposures to different chemicals and frequent exposures to peak levels. This study concluded that chemical exposure in small enterprises is complex in character.

Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of the impact of size on occupational health risk was presented at the Second International Workshop on Benzene in Vienna, 1980. For most of the delegates from the petroleum industry, benzene posed little health risk in the workplace; their workplaces employed sophisticated medical, hygiene and engineering techniques to monitor and eliminate any potential exposure. In contrast, a delegate from Turkey when commenting on the boot-making industry, which to a large extent was a cottage industry carried out in the home, reported that men, women and children were exposed to high concentrations of “an unlabelled solvent”, benzene, which resulted in the occurrence of anaemias and leukaemias (Aksoy et al. 1974). The difference in exposure in the two situations was a direct consequence of workplace size and the more intimate contact of the workers in the cottage-style, boot-making industry, compared with the large-scale petroleum enterprises.

Two Canadian researchers have identified the main difficulties faced by small businesses as: a lack of awareness of health hazards by managers; the higher cost per worker to reduce these hazards; and an unstable competitive climate which makes it unlikely that such businesses can afford to implement the safety standards and regulations (Lees and Zajac 1981).

Thus, much of the experience and recorded evidence indicate that the workers in small enterprises constitute an under-served population from the standpoint of their health and safety. Rantanan (1993) attempted a critical review of available sources for the WHO Interregional Task Group on Health Protection and Health Promotion of Workers in Small Scale Industries, and found that reliable quantitative data on illnesses and injuries to workers in small-scale industries are unfortunately sparse.

In spite of the lack of reliable quantitative data, experience has demonstrated that the characteristics of small-scale industries result in a greater likelihood of musculoskeletal injuries, lacerations, burns, puncture wounds, amputations and fractures, poisonings from inhalation of solvents and other chemicals and, in the rural sector, pesticide poisonings.

Serving the Health Needs of Workers in Small-Scale Enterprises

The difficulty in serving the health and safety needs of workers in small enterprises stems from a number of features:

- Rural enterprises are often isolated as a result of being located at a distance from main centres with bad roads and poor communications.

- Workers on small fishing vessels or in forestry operations also have limited access to health and safety services.

- The home, where most cottage industry and unpaid “housework” is located, is frequently ignored in health and safety legislation.

- Educational levels of workers in small-scale industries are likely to be lower as a result of leaving school earlier or the lack of access to schools. This is accentuated by the employment of children and migrant workers (legal and illegal) who have cultural and language difficulties.

- Although it is clear that small-scale enterprises contribute significantly to the gross domestic product, the fragility of the economies in developing countries makes it difficult to provide funds to serve the health and safety needs of their workers.

- The great number and variability of small-scale enterprises make it difficult to effectively organize health and safety services for them.

In summary, workers in small-scale enterprises have certain characteristics which make them vulnerable to health problems and make it difficult to provide them with health care. These include:

- Inaccessibility to available health services for geographic or economic reasons and a willingness to tolerate unsafe and unhealthy conditions of work, primarily because of poverty or ignorance.

- Deprivation because of poor education, housing, transport and recreation.

- An inability to influence policy making.

What are the Solutions?

These exist at several levels: international, national, regional, local and workplace. They involve policy, education, practice and funding.

A conceptual approach was developed at the Colombo meeting (Colombo Statement 1986), although this looked particularly at developing countries. A restatement of these principles as applicable to small-scale industry, wherever it is located, follows:

- National policies need to be formulated to improve health and safety of all workers in small-scale industries with special emphasis on education and training of managers, supervisors and workers and the means of ensuring that they receive adequate information to protect the health and safety of all workers.

- Occupational health services for small-scale industries need to be integrated with the existing health systems providing primary health care.

- Adequate training for occupational health personnel is needed. This should be tailored to the type of work carried out, and would include training for primary health care workers and specialists as well as the public health inspectors and nurses mentioned above.

- Adequate communication systems are needed to ensure the free flow of occupational health and safety information among workers, management and occupational health personnel at all levels.

- Occupational health care for small isolated groups through primary health care workers (PHCWs) or their equivalent should be provided. In rural areas, such a person is likely to be providing general health care on a part-time basis and an occupational health content can be added. In small urban workplaces, such a situation is less likely. Persons from the workforce selected by their fellow workers will be needed.

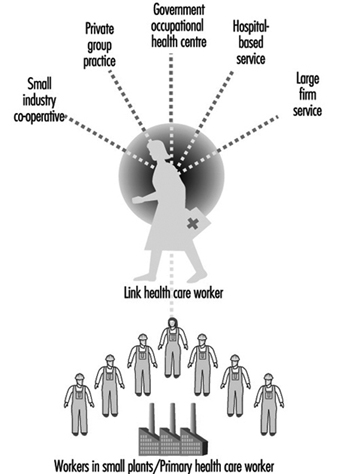

- These rural and urban PHCWs, who will require initial and ongoing training and supervision, need to be linked to the existing health services. The “link health worker” should be an appropriate full-time health professional with at least three years of training. This health professional is the crucial link in the effective functioning of the service. (See figure 1.)

- Occupational hygiene which measures, evaluates and controls environmental hazards, is an essential part of occupational health care. Appropriate occupational hygiene services and skills should be introduced into the service both centrally and peripherally.

Figure 1. Patterns of health care for workers in small plants

Despite the establishment of these principles, very little progress has been made, almost certainly because small workplaces and the workers who work in them are given a low priority in the health service planning of most countries. Reasons for this include:

- lack of political pressure by such workers

- difficulty in servicing the health needs because of such features as isolation, educational levels and innate traditionalism, already mentioned

- the lack of an effective primary health care system.

Approaches to the solution of this problem are international, national and local.

International

A troublesome feature of the global economy is the negative aspects associated with the transfer of technology and the hazardous processes associated with it from developed to developing countries. A second concern is “social dumping”, in which, in order to compete in the global marketplace, wages are lowered, safety standards ignored, hours of work extended, age of employment is lowered and a form of modern-day slavery is instituted. It is urgent that new ILO and WHO instruments (Conventions and Recommendations) banning these practices be developed.

National

All-embracing occupational safety and health legislation is needed, backed up by a will to implement and enforce it. This legislation needs to be supported by positive and widespread health promotion.

Local

There are a number of organizational models for occupational health and safety services which have been successful and which, with appropriate modifications, can accommodate most local situations. They include:

- An occupational health centre can be established in localities where there is a dense population of small workplaces, to provide both accident and emergency treatment as well as education and intervention functions. Such centres are usually supported by government funding, but they may also be funded through a sharing of costs by a number of local small industries, usually on a per-employee basis.

- A big company’s occupational health service may be extended to surrounding small industries.

- A hospital-based occupational health service which already covers accident and emergency services can supplement this with a visiting primary health care service concentrating on education and intervention.

- A service can be provided where a general practitioner provides treatment services in a clinic but uses a visiting occupational health nurse to offer education and intervention in the workplace.

- A specialist occupational health service staffed by a multidisciplinary team comprising occupational physicians, general practitioners, occupational health nurses, physiotherapists and specialists in radiography, pathology and so on, may be established.

- Whatever the model employed, the service must be linked to the workplace by a “link health care worker”, a trained health professional multiskilled in both the clinical and hygiene aspects of the workplace. (See figure 1)

Regardless of the organizational form utilized, the essential functions should include (Glass 1982):

- a centre for training first-aiders among the workers in surrounding small industries

- a centre for the treatment of minor injuries and other work-related health problems

- a centre for the provision of basic biological monitoring including screening examinations of hearing, lung function, vision, blood pressure and so on, as well as the earliest signs of the toxic effects of exposure to occupational hazards

- a centre for the provision of basic environmental investigations to be integrated with the biological monitoring

- a centre for the provision of health and safety education that is directed by or at least coordinated by safety consultants familiar with the kinds of workplaces being served

- a centre from which rehabilitation programmes could be planned, provided and coordinated with return to work.

Conclusion

Small enterprises are a widespread, fundamental and essential form of production. Yet, the workers who work in them frequently lack coverage by health and safety legislation and regulation, and lack adequate occupational health and safety services. Consequently, reflecting the unique characteristics of small enterprises, workers in them have greater exposures to work hazards.

Current trends in the global economy are increasing the extent and the degree of exploitation of workers in small workplaces and, thereby, increasing the risk of exposure to hazardous chemicals. Appropriate international, national and local measures have been designed to diminish such risks and enhance the health and well-being of those working in small-scale enterprises.