The Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (Disabled Persons) Convention, 1983 (No. 159) and Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (Disabled Persons) Recommendation, 1983 (No.168), which supplement and update the Vocational Rehabilitation (Disabled) Recommendation, 1955 (No. 99), are the principal reference documents for a social policy on the issue of disability. However, there are a number of other ILO instruments which explicitly or implicitly make reference to disability. There are notably the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111), the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Recommendation, 1958 (No. 111), the Human Resources Development Convention, 1975 (No. 142) and the Human Resources Development Recommendation, 1975 (No.150)

In addition, important references to disability issues are included in a number of other key ILO instruments, such as: Employment Service Convention, 1948 (No. 88); Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102); Employment Injury Benefits Convention, 1964 (No. 121); Employment Promotion and Protection against Unemployment Convention, 1988 (No. 168); Employment Service Recommendation, 1948 (No. 83); Labour Administration Recommendation, 1978 (No. 158) and Employment Policy (Supplementary Provisions) Recommendation, 1984 (No. 169).

International labour standards treat disability basically under two different headings: as passive measures of income transfer and social protection, and as active measures of training and employment promotion.

One early objective of the ILO was to ensure that workers receive adequate financial compensation for disability, in particular if it was caused in relation to work or war activities. The underlying concern has been to ensure that a damage is adequately compensated, that the employer is liable for accidents and unsafe working conditions, and that in the interest of good labour relations, there should be fair treatment of workers. Adequate compensation is a fundamental element of social justice.

Quite distinct from the compensation objective is the social protection objective. ILO standards which deal with issues of social security look at disability largely as a “contingency” which needs to be covered under social security legislation, the idea being that disability can be a cause of loss of earning capacity and therefore be a legitimate reason to secure income through transfer payments. The principal objective is to provide insurance against loss of income and thus guarantee decent living conditions for people deprived of the means of gaining their own income due to impairment.

In a similar way, policies which pursue a social protection objective tend to provide public assistance to people with disabilities not covered by social insurance. Also in this case the tacit assumption is that disability means incapacity to find adequate income from work, and that a disabled person has therefore to be the responsibility of the public. As a result, disability policy is in many countries predominantly a concern of the social welfare authorities, and the primary policy is that of providing passive measures of financial assistance.

However, those ILO standards which deal explicitly with disabled persons (such as Conventions Nos. 142 and 159, and Recommendations Nos. 99, 150 and 168) treat them as workers and put disability—quite in contrast to the compensation and social protection concepts—in the context of labour market policies, which have as their objective to ensure equality of treatment and opportunity in training and employment, and which look at disabled people as being part of the economically active population. Disability is understood here basically as a condition of occupational disadvantage which can be and should be overcome through a variety of policy measures, regulations, programmes and services.

ILO Recommendation No. 99 (1955), which for the first time invited member States to shift their disability policies from a social welfare or social protection objective towards a labour integration objective, had a profound impact on law in the 1950s and 1960s. But the real breakthrough occurred in 1983 when the International Labour Conference adopted two new instruments, ILO Convention No. 159 and Recommendation No. 168. As of March 1996, 57 out of 169 member States had ratified this Convention.

Many others have readjusted their legislation so as to comply with this Convention even if they have not, or not yet, ratified this international treaty. What distinguishes these new instruments from the former ones is the recognition by the international community and by employers’ and workers’ organizations of the right of disabled persons to equal treatment and opportunity in training and employment.

These three instruments now form a unity. They aim to ensure active labour market participation of disabled people and thus to challenge the sole validity of passive measures or of policies which treat disability as a health problem.

The purposes of the international labour standards which have been adopted with this objective in mind can be described as follows: to remove the barriers which stand in the way of full social participation and integration of disabled people in the mainstream, and to provide the means to promote effectively their economic self-reliance and social independence. These standards oppose a practice that treats disabled people as being outside the norm and excludes them from the mainstream. They object to the tendency of taking disability as a justification for social marginalization and for denying people, on account of their disability, civil and workers’ rights which non-disabled people enjoy as a matter of course.

For the purpose of clarity we may group the provisions of international labour standards which promote the concept of the right of disabled people to active participation in training and employment into two groups: those which address the principle of equal opportunity and those which address the principal of equal treatment.

Equal opportunity: the policy goal which lies behind this formula is to ensure that a disadvantaged population group has access to the same employment and income-earning possibilities and opportunities as the mainstream population.

In order to achieve equal opportunity for disabled people, the pertinent international labour standards have established rules and recommended measures for three types of action:

- Action to empower the disabled individual to achieve the level of competencies and abilities required to take advantage of employment opportunity and to provide the technical means and the required assistance which would enable that individual to cope with the demands of a job. This type of action is what essentially constitutes the process of vocational rehabilitation.

- Action which helps to adjust the environment to the special needs of disabled persons, such as worksite, job, machine or tool adaptations as well as legal and promotional action which helps to overcome negative and discriminatory attitudes that cause exclusion.

- Action which ensures disabled people real employment opportunities. This includes legislation and policies which favour remunerative work over passive income support measures, as well as those which entice employers to employ, or to maintain in employment, workers with a disability.

- Action which sets employment targets or establishes quotas or levies (fines) under affirmative action programmes. It also includes services by which labour administrations and other bodies may assist disabled people to find jobs and to advance in their careers.

Therefore, these standards, which have been developed to guarantee equality of opportunity, imply the promotion of special positive measures to help disabled people make the transition into active life or to prevent unnecessary, unwarranted transition into a life reliant upon passive income support. Policies geared to establish equality of opportunity are, therefore, usually concerned with the development of support systems and special measures to bring about effective equality of opportunities, which are justified by the need to compensate for the real or presumed disadvantages of disability. In ILO legal parlance: “Special positive measures aimed at effective equality of opportunity … between disabled workers and other workers shall not be regarded as discriminating against other workers” (Convention No. 159, Article 4).

Equal treatment: The precept of equal treatment has a related but distinct objective. Here the issue is that of human rights, and the regulations which ILO member States have agreed to observe have precise legal implications and are subject to monitoring and—in case of violation—to legal recourse and/or arbitration.

ILO Convention No. 159 established equal treatment as a guaranteed right. It furthermore specified that equality has to be “effective”. This means that conditions should be such as to ensure that the equality is not only formal but real and that the situation resulting from such treatment puts the disabled person into an “equitable” position, that is one which corresponds by its results and not by its measures to that of non-disabled persons. For example, to assign a disabled worker the same job as a non-disabled worker is not equitable treatment if the worksite is not fully accessible or if the job is not suited to the disability.

Present Legislation on Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment of Disabled Persons

Each country has a different history of vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons. The legislation of member States varies due to their different stages of industrial development, social and economic situations, and so on. For example, some countries already had legislation on disabled persons before the Second World War, deriving from disability measures for disabled veterans or poor people at the beginning of this century. Other countries started to take concrete measures to support disabled persons after the Second World War, and established legislation in the field of vocational rehabilitation. This was often expanded following the adoption of the Vocational Rehabilitation of the Disabled Recommendation, 1955 (No. 99) (ILO 1955). Other countries only recently started taking measures for disabled persons due to the awareness created by the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981, the adoption of ILO Convention No.159 and Recommendation No. 168 in 1983 and the United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons (1983–1992).

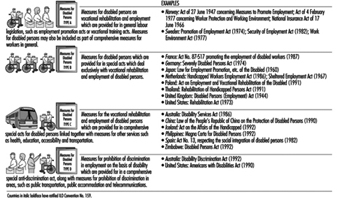

The current legislation on vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons is divided into four types according to different historical backgrounds and policies (figure 1).

Figure 1. Four types of legislation on rights of persons with disabilities.

We must realize that there are no clear divisions between these four groups and that they may overlap. Legislation in a country may correspond not only to one type, but to several. For example, the legislation of many countries is a combination of two types or more. It seems that the legislation of Type A is formulated in the early stage of measures for disabled persons, whereas the legislation of Type B is from a later stage. The legislation of Type D, namely the prohibition of discrimination because of disabilities, has been growing in recent years, supplementing the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, political opinion and so on. The comprehensive nature of legislation of Types C and D may be used as models for those developing countries which have not yet formulated any concrete legislation on disability.

Sample Measures of each Type

In the following paragraphs, the structure of legislation and measures stipulated are outlined by some examples of each type. As measures for vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons in each country are often more or less the same, regardless of the type of legislation in which they are provided for, some overlaps occur.

Type A: Measures for disabled persons on vocational rehabilitation and employment which are provided for in general labour legislation such as employment promotion acts or vocational training acts. Measures for disabled persons may also be included as part of comprehensive measures for workers in general.

The characteristic of this type of legislation is that measures for disabled people are provided for in the acts which apply to all workers, including disabled workers, and to all enterprises employing workers. As measures on employment promotion and employment security for disabled persons are basically incorporated as part of comprehensive measures for workers in general, the national policy gives priority to internal rehabilitation efforts of enterprises and to preventive activities and early intervention in working environments. To this end, working environment committees, which consist of employers, workers and safety and health personnel are often set up in enterprises. The details of the measures tend to be provided for in regulations or rules under the acts.

For example, the Working Environment Act of Norway applies to all workers employed by most enterprises in the country. Some special measures for handicapped persons are incorporated: (1) Passageways, sanitary facilities, technical installations and equipment shall be designed and arranged so that handicapped persons can work in the enterprise, as far as possible. (2) If a worker has become handicapped in the workplace as a result of accident or sickness the employer shall, as far as possible, take the necessary measures to enable the worker to obtain or retain suitable employment. The worker shall preferably be given an opportunity to continue his or her former work, possibly after special adaptation of the work activity, alteration of technical installations, rehabilitation or retraining and so on. The following are examples of action that must be taken by the employer:

- procurement of or changes to technical equipment used by the worker—for instance, tools, machinery, and so on

- alterations to the workplace—this could refer to alterations to furniture and equipment, or to alterations to doorways, thresholds, installation of lifts, procurement of wheelchair ramps, repositioning of door handles and light switches, and so on

- organization of the work—this could involve alteration of routines, changes in working hours, active participation by other workers; for instance, recording on and transcribing from a dictaphone cassette

- measures in connection with training and retraining.

In addition to these measures, there is a system which provides employers of handicapped persons with subsidies concerning the additional cost to adapt the workplace to the worker, or vice versa.

Type B: Measures for disabled persons which are provided for in special acts which deal exclusively with vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons.

This type of legislation usually has specific provisions on vocational rehabilitation and employment dealing with various measures, while other measures for disabled people are stipulated in other acts.

For example, the Severely Disabled Persons Act of Germany provides for the following special assistance for disabled persons to improve their employment opportunities, as well as vocational guidance and placement services:

- vocational training in enterprises and training centres or in special vocational rehabilitation institutions

- special benefits for disabled persons or employers—payment of application and removal costs, transitional allowances, technical adaptation of workplaces, payment of housing costs, assistance in acquiring a special vehicle or additional special equipment or in obtaining a driving licence

- the obligation for public and private employers to reserve 6% of their workplaces for severely disabled persons; compensation payments must be paid in respect of the places not filled in this manner

- special protection against dismissal for all severely disabled persons after a period of six months

- representation of the interests of severely disabled persons in the enterprise by means of a staff counsellor

- supplementary benefits for severely disabled persons to ensure their integration into occupation and employment

- special workshops for disabled persons who are unable to work on the general labour market because of the nature or severity of their impediment

- grants for employers of up to 80% of the wage paid to disabled persons for a period of two years, as well as payments in respect of the adaptation of workplaces and the establishment of specified probationary periods of employment.

Type C: Measures for the vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons which are provided for in comprehensive special acts for disabled persons linked together with measures for other services such as health, education, accessibility and transportation.

This type of legislation usually has general provisions concerning the purpose, declaration of policy, coverage, definition of terms in the first chapter, and after that several chapters which deal with services in the fields of employment or vocational rehabilitation as well as health, education, accessibility, transportation, telecommunications, auxiliary social services and so on.

For example, the Magna Carta for Disabled Persons of the Philippines provides for the principle of equal opportunity for employment. The following are several measures from chapter on employment:

- 5% of reserved employment for disabled persons in departments or agencies of the government

- incentives for employers such as a deduction from their taxable income equivalent to a certain part of the wages of disabled persons or of the costs of improvements or modifications of facilities

- vocational rehabilitation measures that serve to develop the skills and potentials of disabled persons and enable them to compete favourably for available productive and remunerative employment opportunities, consistent with the principle of equal opportunity for disabled workers and workers in general

- vocational rehabilitation and livelihood services for disabled people in the rural areas

- vocational guidance, counselling and training to enable disabled persons to secure, retain and advance in employment, and the availability and training of counsellors and other suitably qualified staff responsible for these services

- government-owned vocational and technical schools in every province for a special vocational and technical training programme for disabled persons

- sheltered workshops for disabled individuals who cannot find suitable employment in the open labour market

- apprenticeship.

Furthermore, this act has provisions concerning prohibition of discrimination against disabled persons in employment.

Type D: Measures for prohibition of discrimination in employment on the basis of disability which are provided for in a comprehensive special anti-discrimination act along with measures for prohibition of discrimination in areas such as public transportation, public accommodation and telecommunications.

The feature of this type of legislation is that there are provisions which deal with discrimination on the ground of disability in employment, public transportation, accommodation, telecommunications and so on. Measures for vocational rehabilitation services and the employment of disabled people are provided for in other acts or regulations.

For example, the Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination in such important areas as employment, access to public accommodations, telecommunications, transportation, voting, public services, education, housing and recreation. As for employment in particular, the Act prohibits employment discrimination against “qualified individuals with a disability” who, with or without “reasonable accommodation”, can perform the essential functions of the job, unless such accommodation would impose “undue hardship” on the operation of the business. The Act prohibits discrimination in all employment practices, including job application procedures, hiring, firing, advancement, compensation, training and other terms, conditions and privileges of employment. It applies to recruitment, advertising, tenure, layoff, leave, fringe benefits and all other employment-related activities.

In Australia, the purpose of the Disability Discrimination Act is to provide improved opportunities for people with a disability and to assist in breaking down barriers to their participation in the labour market and other areas of life. The Act bans discrimination against people on the grounds of disability in employment, accommodation, recreation and leisure activities. This complements existing anti-discrimination legislation that outlaws discrimination on the grounds of race or gender.

Quota/Levy Legislation or Anti-discrimination Legislation?

The structure of national legislation on vocational rehabilitation and employment of disabled persons varies somewhat from country to country, and it is therefore difficult to determine which type of legislation is best. However, two types of legislation, namely quota or levy legislation and anti-discrimination legislation, seem to emerge as the two main legislative modes.

Although some European countries, among others, have quota systems which are usually provided in the legislation of Type B, they are quite different in some points, such as the category of disabled persons to whom the system is applied, the category of employers on whom the employment obligation is imposed (for example, size of the enterprise or public sector only) and the employment rate (3%, 6%, etc.). In most countries the quota system is accompanied by a levy or grant system. Quota provisions are also included in the legislation of non-industrialized countries as varied as Angola, Mauritius, the Philippines, Tanzania and Poland. China is also examining the possibility of introducing a quota system.

There is no doubt that a quota system that is enforceable could contribute considerably to raising the employment levels of disabled persons in the open labour market. Also, the system of levies and grants helps to rectify the financial inequality between the employers who try to employ disabled workers and the ones who do not, while levies contribute to accumulating valuable resources that are needed to finance vocational rehabilitation and incentives for employers.

On the other hand, one of the problems of the system is the fact that it requires a clear definition of disability for recognizing qualification, and strict rules and procedures for registration, and therefore it may raise the problem of stigma. There may also be the potential discomfort of a disabled person being at a place of employment where he or she is not wanted by the employer but is merely tolerated to avoid legal sanctions. In addition, credible enforcement mechanisms and their effective application are required for quota legislation to achieve results.

Anti-discrimination legislation (Type D) seems to be more appropriate for the principle of normalization, ensuring disabled persons equal opportunities in society, because it promotes employers’ initiatives and social consciousness by means of environmental improvement, not employment obligation.

On the other hand, some countries have difficulties in enforcing anti-discrimination legislation. For example, remedial action usually requires a victim to play the role of complainant, and in some cases it is difficult to prove discrimination. Also the process of remedial action commonly takes a long time because a lot of complaints of discrimination on the basis of disability are sent to courts or equal rights commissions. It is generally admitted that anti-discrimination legislation has still to prove its effectiveness in placing and maintaining large numbers of disabled workers in employment.

Future Trends

Although it is difficult to forecast future trends in legislation, it appears that anti-discrimination acts (Type D) are one stream which both developed countries and developing countries will consider.

It seems that industrialized countries with a history of quota or quota/levy legislation will watch the experience of countries such as the United States and Australia before taking action to adjust their own legislative systems. In particular in Europe, with its concepts of redistributive justice, it is likely that the prevailing legislative systems will be maintained, while, however, introducing or strengthening anti-discrimination provisions as an additional legislative feature.

In a few countries like the United States, Australia and Canada, it could be politically difficult to legislate a quota system for disabled people without having quota provisions also in relation to other population groups that experience disadvantages in the labour market, such as women and ethnic and racial minority groups currently covered by human rights or employment equity legislation. Although a quota system would have some advantages for disabled people, the administrative apparatus required for such a multicategory quota system would be enormous.

It appears that developing countries which have no disability legislation may choose legislation of Type C, including a few provisions concerning prohibition of discrimination, because it is the more comprehensive approach. The risk of this approach, however, is that comprehensive legislation which cuts across the responsibility of many ministries becomes the affair of a single ministry, mostly that responsible for social welfare. This may be counterproductive, reinforce segregation and weaken the government’s ability to implement the law. Experience shows that comprehensive legislation looks good on paper, but is rarely applied.