Labour or Industrial Relations

The term labour relations, also known as industrial relations, refers to the system in which employers, workers and their representatives and, directly or indirectly, the government interact to set the ground rules for the governance of work relationships. It also describes a field of study dedicated to examining such relationships. The field is an outgrowth of the industrial revolution, whose excesses led to the emergence of trade unions to represent workers and to the development of collective labour relations. A labour or industrial relations system reflects the interaction between the main actors in it: the state, the employer (or employers or an employers’ association), trade unions and employees (who may participate or not in unions and other bodies affording workers’ representation). The phrases “labour relations” and “industrial relations” are also used in connection with various forms of workers’ participation; they can also encompass individual employment relationships between an employer and a worker under a written or implied contract of employment, although these are usually referred to as “employment relations”. There is considerable variation in the use of the terms, partly reflecting the evolving nature of the field over time and place. There is general agreement, however, that the field embraces collective bargaining, various forms of workers’ participation (such as works councils and joint health and safety committees) and mechanisms for resolving collective and individual disputes. The wide variety of labour relations systems throughout the world has meant that comparative studies and identification of types are accompanied by caveats about the limitations of over-generalization and false analogies. Traditionally, four distinct types of workplace governance have been described: dictatorial, paternalistic, institutional and worker-participative; this chapter examines primarily the latter two types.

Both private and public interests are at stake in any labour relations system. The state is an actor in the system as well, although its role varies from active to passive in different countries. The nature of the relationships among organized labour, employers and the government with respect to health and safety are indicative of the overall status of industrial relations in a country or an industry and the obverse is equally the case. An underdeveloped labour relations system tends to be authoritarian, with rules dictated by an employer without direct or indirect employee involvement except at the point of accepting employment on the terms offered.

A labour relations system incorporates both societal values (e.g., freedom of association, a sense of group solidarity, search for maximized profits) and techniques (e.g., methods of negotiation, work organization, consultation and dispute resolution). Traditionally, labour relations systems have been categorized along national lines, but the validity of this is waning in the face of increasingly varied practices within countries and the rise of a more global economy driven by international competition. Some countries have been characterized as having cooperative labour relations models (e.g., Belgium, Germany), whereas others are known as being conflictual (e.g., Bangladesh, Canada, United States). Different systems have also been distinguished on the basis of having centralized collective bargaining (e.g., those in Nordic countries, although there is a move away from this, as illustrated by Sweden), bargaining at the sectoral or industrial level (e.g., Germany), or bargaining at the enterprise or plant level (e.g., Japan, the United States). In countries having moved from planned to free-market economies, labour relations systems are in transition. There is also increasing analytical work being done on the typologies of individual employment relationships as indic- ators of types of labour relations systems.

Even the more classic portrayals of labour relations systems are not by any means static characterizations, since any such system changes to meet new circumstances, whether economic or political. The globalization of the market economy, the weakening of the state as an effective force and the ebbing of trade union power in many industrialized countries pose serious challenges to traditional labour relations systems. Technological development has brought changes in the content and organization of work that also have a crucial impact on the extent to which collective labour relations can develop and the direction they take. Employees’ traditionally shared work schedule and common workplace have increasingly given way to more varied working hours and to the performance of work at varied locations, including home, with less direct employer supervision. What have been termed “atypical” employment relationships are becoming less so, as the contingent workforce continues to expand. This in turn places pressure on established labour relations systems.

Newer forms of employee representation and participation are adding an additional dimension to the labour relations picture in a number of countries. A labour relations system sets the formal or informal ground rules for determining the nature of collective industrial relations as well as the framework for individual employment relationships between a worker and his or her employer. Complicating the scene at the management end are additional players such as temporary employment agencies, labour contractors and job contractors who may have responsibilities towards workers without having control over the physical environment in which the work is carried out or the opportunity to provide safety training. In addition, public sector and private sector employers are governed by separate legislation in most countries, with the rights and protections of employees in these two sectors often differing significantly. Moreover, the private sector is influenced by forces of international competition that do not directly touch public-sector labour relations.

Finally, neoliberal ideology favouring the conclusion of indi-vidualized employment contracts to the detriment of collectively bargained arrangements poses another threat to traditional labour relations systems. Those systems have developed as a result of the emergence of collective representation for workers, based on past experience that an individual worker’s power is weak when compared to that of the employer. Abandoning all collective representation would risk returning to a nineteenth century concept in which acceptance of hazardous work was largely regarded as a matter of individual free choice. The increasingly globalized economy, the accelerated pace of technological change and the resultant call for greater flexibility on the part of industrial relations institutions, however, pose new challenges for their survival and prosperity. Depending upon their existing traditions and institutions, the parties involved in a labour relations system may react quite differently to the same pressures, just as management may choose a cost-based or a value-added strategy for confronting increased competition (Locke, Kochan and Piore, 1995). The extent to which workers’ participation and/or collective bargaining are regular features of a labour relations system will most certainly have an impact on how management confronts health and safety problems.

Moreover, there is another constant: the economic dependence of an individual worker on an employer remains the underlying fact of their relationship–one that has serious potential consequences when it comes to safety and health. The employer is seen as having a general duty to provide a safe and healthful workplace and to train and equip workers to do their jobs safely. The worker has a reciprocal duty to follow safety and health instructions and to refrain from harming himself/herself or others while at work. Failure to live up to these or other duties can lead to disputes, which depend on the labour relations system for their resolution. Dispute resolution mechanisms include rules governing not only work stoppages (strikes, slowdowns or go-slows, work to rule, etc.) and lockouts, but the discipline and dismissal of employees as well. Additionally, in many countries employers are required to participate in various institutions dealing with safety and health, perform safety and health monitoring, report on-the-job accidents and diseases and, indirectly, to compensate workers who are found to be suffering from an occupational injury or disease.

Human Resources Management

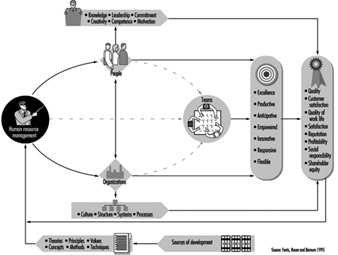

Human resources management has been defined as “the science and the practice that deals with the nature of the employment relationship and all of the decisions, actions and issues that relate to that relationship” (Ferris, Rosen and Barnum 1995; see figure 1). It encapsulates employer-formulated policies and practices that see the utilization and management of employees as a business resource in the context of a firm’s overall strategy to enhance productivity and competitiveness. It is a term most often used to describe an employer’s approach to personnel administration that emphasizes employee involvement, normally but not always in a union-free setting, with the goal of motivating workers to enhance their productivity. The field was formed from a merger of scientific management theories, welfare work and industrial psychology around the time of the First World War and has undergone considerable evolution since. Today, it stresses work organization techniques, recruitment and selection, performance appraisal, training, upgrading of skills and career development, along with direct employee participation and communication. Human resources management has been put forth as an alternative to “Fordism”, the traditional assembly-line type of production in which engineers are responsible for work organization and workers’ assigned tasks are divided up and narrowly circumscribed. Common forms of employee involvement include suggestion schemes, attitude surveys, job enrichment schemes, teamworking and similar forms of empowerment schemes, quality of working-life programmes, quality circles and task forces. Another feature of human resources management may be linking pay, individually or collectively, to performance. It is noteworthy that one of the three objectives of occupational health has been identified by the Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health as “development of work organizations and working cultures in a direction which supports health and safety at work and in doing so also promotes a positive social climate and smooth operation and may enhance productivity of the undertakings...” (ILO 1995b). This is known as developing a “safety culture.”

Figure 1. The role of human resources management in adding value to people and to organizations

The example of a safety performance management programme illustrates some human resource management theories in the context of occupational safety and health. As described by Reber, Wallin and Duhon (1993), this approach has had considerable success in reducing lost time on account of accidents. It relies on specifying safe and unsafe behaviours, teaching employees how to recognize safe behaviour and motivating them to follow the safety rules with goal setting and feedback. The programme relies heavily on a training technique whereby employees are shown safe, correct methods via videotapes or live models. They then have a chance to practice new behaviours and are provided with frequent performance feedback. In addition, some companies offer tangible prizes and rewards for engaging in safe behaviour (rather than simply for having fewer accidents). Employee consultation is an important feature of the programme as well.

The implications of human resources management for industrial relations practices remain a source of some controversy. This is particularly the case for types of workers’ participation schemes that are perceived by trade unions as a threat. In some instances human resources management strategies are pursued alongside collective bargaining; in other cases the human resources management approach seeks to supplant or prevent the activities of independent organizations of workers in defence of their interests. Proponents of human resources management maintain that since the 1970s, the personnel management side of human resources management has evolved from being a maintenance function, secondary to the industrial relations function, to being one of critical importance to the effectiveness of an organization (Ferris, Rosen and Barnum 1995). Since human resources management is a tool for management to employ as part of its personnel policy rather than a relationship between an employer and workers’ chosen representatives, it is not the focus of this chapter.

The articles which follow describe the main parties in a labour relations system and the basic principles underpinning their interaction: rights to freedom of association and representation. A natural corollary to freedom of association is the right to engage in collective bargaining, a phenomenon which must be distinguished from consultative and non-union worker participation arrangements. Collective bargaining takes place as negotiations between representatives chosen by the workers and those acting on behalf of the employer; it leads to a mutually accepted, binding agreement that can cover a wide range of subjects. Other forms of workers’ participation, national-level consultative bodies, works councils and enterprise-level health and safety representatives are also important features of some labour relations systems and are thus examined in this chapter. Consultation can take various forms and occur at different levels, with national-, regional- and/or industrial- and enterprise-level arrangements. Worker representatives in consultative bodies may or may not have been selected by the workers and there is no obligation for the state or the employer to follow the wishes of those representatives or to abide by the results of the consultative process. In some countries, collective bargaining and consultative arrangements exist side by side and, to work properly, must be carefully intermeshed. For both, rights to information about health and safety and training are crucial. Finally, this chapter takes into account that in any labour relations system, disputes may arise, whether they are individual or collective. Safety and health issues can lead to labour relations strife, producing work stoppages. The chapter thus concludes with descriptions of how labour relations disputes are resolved, including by arbitration, mediation or resort to the regular or labour courts, preceded by a discussion of the role of the labour inspectorate in the context of labour relations.

The Actors in the Labour Relations System

Classically, three actors have been identified as parties to the labour relations system: the state, employers and workers’ representatives. To this picture must now be added the forces that transcend these categories: regional and other multilateral economic integration arrangements among states and multinational corporations as employers which do not have a national identity but which also can be seen as labour market institutions. Since the impact of these phenomena on labour relations remains unclear in many respects, however, discussion will focus on the more classic actors despite this caveat of the limitation of such an analysis in an increasingly global community. In addition, greater emphasis is needed on analysing the role of the individual employment relationship in labour relations systems and on the impact of the emerging alternative forms of work.

The State

The state always has at least an indirect effect on all labour relations. As the source of legislation, the state exerts an inevitable influence on the emergence and development of a labour relations system. Laws can hinder or foster, directly or indirectly, the establishment of organizations representing workers and employers. Legislation also sets a minimum level of worker protection and lays down “the rules of the game”. To take an example, it can provide lesser or greater protection for a worker who refuses to perform work he or she reasonably considers to be too hazardous, or for one who acts as a health and safety representative.

Through the development of its labour administration, the state also has an impact on how a labour relations system may function. If effective enforcement of the law is afforded through a labour inspectorate, collective bargaining can pick up where the law leaves off. If, however, the state infrastructure for having rights vindicated or for assisting in the resolution of disputes that emerge between employers and workers is weak, they will be left more to their own devices to develop alternative institutions or arrangements.

The extent to which the state has built up a well-functioning court or other dispute resolution system may also have an influence on the course of labour relations. The ease with which workers, employers and their respective organizations may enforce their legal rights can be as important as the rights themselves. Thus the decision by a government to set up special tribunals or administrative bodies to deal with labour disputes and/or disagreements over individual employment problems can be an expression of the priority given to such issues in that society.

In many countries, the state has a direct role to play in labour relations. In countries that do not respect freedom of association principles, this may involve outright control of employers’ and workers’ organizations or interference with their activities. The state may attempt to invalidate collective bargaining agreements that it perceives as interfering with its economic policy goals. Generally speaking, however, the role of the state in industrialized countries has tended to promote orderly industrial relations by providing the necessary legislative framework, including minimum levels of worker protection and offering parties information, advice and dispute settlement services. This could take the form of mere toleration of labour relations institutions and the actors in them; it could move beyond to actively encourage such institutions. In a few countries, the state is a more active participant in the industrial relations system, which includes national level tripartite negotiations. For decades in Belgium and more recently in Ireland, for instance, government representatives have been sitting down alongside those from employer and trade union circles to hammer out a national level agreement or pact on a wide range of labour and social issues. Tripartite machinery to fix minimum wages has long been a feature of labour relations in Argentina and Mexico, for example. The interest of the state in doing so derives from its desires to move the national economy in a certain direction and to maintain social peace for the duration of the pact; such bipartite or tripartite arrangements create what has been called a “social dialogue”, as it has developed in Australia (until 1994), Austria, Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands, for instance. The pros and cons of what have been termed “corporatist” or “neocorporatist” approaches to labour relations have been extensively debated over the years. With its tripartite structure, the International Labour Organization has long been a proponent of strong tripartite cooperation in which the “social partners” play a significant role in shaping government policy on a wide range of issues.

In some countries, the very idea of the state becoming involved as a negotiator in private sector bargaining is unthinkable, as in Germany or the United States. In such systems, the role of the state is, aside from its legislative function, generally restricted to providing assistance to the parties in reaching an agreement, such as in offering voluntary mediation services. Whether active or passive, however, the state is a constant partner in any labour relations system. In addition, where the state is itself the employer, or an enterprise is publicly owned, it is of course directly involved in labour relations with the employees and their representatives. In this context, the state is motivated by its role as provider of public services and/or as an economic actor.

Finally, the impact of regional economic integration arrangements on state policy is also felt in the labour relations field. Within the European Union, practice in member countries has changed to reflect directives dealing with consultation of workers and their representatives, including those on health and safety matters in particular. Multilateral trade agreements, such as the labour side agreement to the North American Free Trade Agreement (Canada, Mexico, United States) or the agreements implementing the Mercosur Common Market (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, thought soon to be joined by Bolivia and Chile) also sometimes contain workers’ rights provisions or mechanisms that over time may have an indirect impact on labour relations systems of the participating states.

Employers

Employers–that is, providers of work–are usually differentiated in industrial relations systems depending upon whether they are in the private or the public sector. Historically, trade unionism and collective bargaining developed first in the private sector, but in recent years these phenomena have spread to many public sector settings as well. The position of state-owned enterprises—which in any event are dwindling in number around the world—as employers, varies depending upon the country. (They still play a key role in China, India, Viet Nam and in many African countries.) In Eastern and Central Europe, one of the major challenges of the post-Communist era has been the establishment of independent organizations of employers.

International Employers’ Organizations

Based in Geneva, Switzerland, the International Organization of Employers (IOE) in 1996 grouped 118 central national organizations of employers in 116 countries. The exact form of each member organization may differ from country to country, but in order to qualify for membership in the IOE an employers’ organization must meet certain conditions: it must be the most representative organization of employers - exclusively of employers - in the country; it must be voluntary and independent, free from outside interference; and it must stand for and defend the principles of free enterprise. Members include employer federations and confederations, chambers of commerce and industry, councils and associations. Regional or sectoral organizations cannot become members; nor can enterprises, regardless of their size or importance, affiliate themselves directly with the IOE - a factor that has served to ensure that its voice is representative of the employer community at large, and not of the particular interests of individual enterprises or sectors.

The IOE’s main activity, however, is to organize employers whenever they have to deal with social and labour matters at the global level. In practice, most of this takes place in the ILO, which has responsibility for these questions in the United Nations system. The IOE also has Category I consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations, where it intervenes whenever matters of interest or consequence to employers arise.

The IOE is one of only two organizations that the employer community has set up to represent the interests of enterprise globally. The other is the International Chamber of Commerce, with its headquarters in Paris, which concerns itself principally with economic matters. While structurally quite different, the two organizations complement each other. They cooperate on the basis of an agreement which defines their areas of responsibility as well as through good personal relations between their representatives and, to a degree, on a common membership base. Many subjects cut across their mandates, of course, but are dealt with pragmatically without friction. On certain issues, such as multinational enterprises, the two organizations even act in unison.

by Chapter Editor (excerpted from: ILO 1994)

In the private sector, the situation has been summed up as follows:

Employers have common interests to defend and precise causes to advance. In organizing themselves, they pursue several aims which in turn determine the character of their organizations. These can be chambers of commerce, economic federations and employers’ organizations (for social and labour matters) ... Where issues centre essentially on social matters and industrial relations, including collective bargaining, occupational health and safety, human resource development, labour law and wages, the desire for co-ordinated action has led to the creation of employers’ organizations, which are always voluntary in nature ... (ILO 1994a).

Some employers’ organizations were initially established in response to pressure from the trade unions to negotiate, but others may be traced to medieval guilds or other groups founded to defend particular market interests. Employers’ organizations have been described as formal groups of employers set up to defend, represent and advise affiliated employers and to strengthen their position in society at large with respect to labour matters as distinct from economic matters ... Unlike trade unions, which are composed of individual persons, employers’ organizations are composed of enterprises (Oechslin 1995).

As identified by Oechslin, there tend to be three main functions (to some extent overlapping) common to all employers’ organizations: defence and promotion of their members’ interests, representation in the political structure and provision of services to their members. The first function is reflected largely in lobbying government to adopt policies that are friendly to employers’ interests and in influencing public opinion, chiefly through media campaigns. The representative function may occur in the political structure or in industrial relations institutions. Political representation is found in systems where consultation of interested economic groups is foreseen by law (e.g., Switzerland), where economic and social councils provide for employer representation (e.g., France, French-speaking African countries and the Netherlands) and where there is participation in tripartite forums such as the International Labour Conference and other aspects of ILO activity. In addition, employers’ organizations can exercise considerable influence at the regional level (especially within the European Union).

The way in which the representative function in the industrial relations system occurs depends very much on the level at which collective bargaining takes place in a particular country. This factor also largely determines the structure of an employers’ organization. If bargaining is centralized at the national level, the employers’ organization will reflect that in its internal structure and operations (central economic and statistical data bank, creation of a mutual strike insurance system, strong sense of member discipline, etc.). Even in countries where bargaining takes place at the enterprise level (such as Japan or the United States), the employers’ organization can offer its members information, guidelines and advice. Bargaining that takes place at the industrial level (as in Germany, where, however, some employers have recently broken ranks with their associations) or at multiple levels (as in France or Italy) of course also influences the structure of employers’ organizations.

As for the third function, Oechslin notes, “it is not always easy to draw a line between activities supporting the functions described above and those undertaken for the members in their interest” (p. 42). Research is the prime example, since it can be used for multiple purposes. Safety and health is an area in which data and information can be usefully shared by employers across sectors. Often, new concepts or reactions to novel developments in the world of work have been the product of broad reflection within employers’ organizations. These groups also provide training to members on a wide range of management issues and have undertaken social affairs action, such as in the development of workers’ housing or support for community activities. In some countries, employers’ organizations provide assistance to their members in labour court cases.

The structure of employers’ organizations will depend not only on the level at which bargaining is done, but also on the country’s size, political system and sometimes religious traditions. In developing countries, the main challenge has been the integration of a very heterogeneous membership that may include small and medium-sized businesses, state enterprises and subsidiaries of multinational corporations. The strength of an employers’ organi-zation is reflected in the resources its members are willing to devote to it, whether in the form of dues and contributions or in terms of their expertise and time.

The size of an enterprise is a major determinant in its approach to labour relations, with the employer of a small workforce being more likely to rely on informal means for dealing with its workers. Small and medium-sized enterprises, which are variously defined, sometimes fall under the threshold for legally mandated workers’ participation schemes. Where collective bargaining occurs at the enterprise level, it is much more likely to exist in large firms; where it takes place at the industry or national level, it is more likely to have an effect in areas where large firms have historically dominated the private sector market.

As interest organizations, employers’ organizations—like trade unions—have their own problems in the areas of leadership, internal decision-making and member participation. Since employers tend to be individualists, however, the challenge of marshalling discipline among the membership is even greater for employers’ organizations. As van Waarden notes (1995), “employers’ associations generally have high density ratios ... However, employers find it a much greater sacrifice to comply with the decisions and regulations of their associations, as these reduce their much cherished freedom of enterprise.” Trends in the structure of employers’ organizations very much reflect those of the labour market– towards or against centralization, in favour of or opposed to regulation of competition. Van Waarden continues: “even if the pressure to become more flexible in the ‘post-Fordist’ era continues, it does not necessarily make employers’ associations redundant or less influential ... [They] would still play an important role, namely as a forum for the coordination of labour market policies behind the scenes and as an advisor for firms or branch associations engaged in collective bargaining” (ibid., p. 104). They can also perform a solidarity function; through employers’ associations, small employers may have access to legal or advisory services they otherwise could not afford.

Public employers have come to see themselves as such only relatively recently. Initially, the government took the position that a worker’s involvement in trade union activity was incompatible with service to the sovereign state. They later resisted calls to engage in collective bargaining with the argument that the legislature, not the public administration, was the paymaster and that it was thus impossible for the administration to enter into an agreement. These arguments, however, did not prevent (often unlawful) public sector strikes in many countries and they have fallen by the wayside. In 1978, the International Labour Conference adopted the Labour Relations (Public Service) Convention (No. 151) and Recommendation (No. 159) on public employees’ right to organize and on procedures for determining their terms and conditions of employment. Collective bargaining in the public sector is now a way of life in many developed countries (e.g., Australia, France, United Kingdom) as well as in some developing countries (e.g., many francophone African countries and many countries in Latin America).

The level of employer representation in the public sector depends largely upon the political system of the country. In some this is a centralized function (as in France) whereas in others it reflects the various divisions of government (as in the United States, where bargaining can take place at the federal, state and municipal levels). Germany presents an interesting case in which the thousands of local communities have banded together to have a single bargaining agent deal with the unions in the public sector throughout the country.

Because public sector employers are already part of the state, they do not fall under laws requiring registration of employers’ organizations. The designation of the bargaining agent in the public sector varies considerably by country; it may be the Public Service Commission, the Ministry of Labour, the Ministry of Finance or another entity altogether. The positions taken by a public employer in dealing with employees in this sector tend to follow the political orientation of the ruling political party. This may range from taking a particular stance in bargaining to a flat-out denial of the right of public employees to organize into trade unions. However, while as an employer the public service is shrinking in many countries, there is an increasing readiness on its part to engage in bargaining and consultations with employee representatives.

International Labour Federations

The international labour movement on a global, as opposed to a regional or national level, consists of international associations of national federations of labour unions. There are currently three such internationals, reflecting different ideological tendencies: the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) and the relatively small, originally Christian, World Congress of Labour (WCL). The ICFTU is the largest, with 174 affiliated unions from 124 countries in 1995, representing 116 million trade union members. These groups lobby intergovernmental organizations on overall economic and social policy and press for worldwide protection of basic trade union rights. They can be thought of as the political force behind the international labour movement.

The industrial force of the international labour movement lies in the international associations of specific labour unions, usually drawn from one trade, industry or economic sector. Known as International Trade Secretariats (ITSs) or Trade Union Internationals (TUIs), they may be independent, affiliated to, or controlled by the internationals. Coverage has traditionally been by sector, but also in some cases is by employee category (such as white-collar workers), or by employer (public or private). For example, in 1995 there were 13 operative ITSs aligned with the ICFTU, distributed as follows: building and woodworking; chemical and mining, energy; commercial, clerical, professional and technical; education; entertainment; food, agriculture, restaurant and catering; graphic arts; journalism; metalworking; postal and telecommunications; public service; textile, garment and leather work; transport. The ITSs concentrate mainly on industry-specific issues, such as industrial disputes and pay rates, but also the application of health and safety provisions in a specific sector. They provide information, education, training and other services to affiliated unions. They also help coordinate international solidarity between unions in different countries, and represent the interests of workers in various international and regional forums.

Such action is illustrated by the international trade union response to the incident at Bhopal, India, involving the leak of methyl isocyanate, which claimed thousands of victims on 3 December 1984. At the request of their Indian national trade union affiliates, the ICFTU and the International Federation of Chemical, Energy, Mine and General Workers’ Unions (ICEM) sent a mission to Bhopal to study the causes and effects of the gas leak. The report contained recommendations for preventing similar disasters and endorsed a list of safety principles; this report has been used by trade unionists in both industrialized and developing countries as a basis of programmes for improving health and safety at work.

Source: Rice 1995.

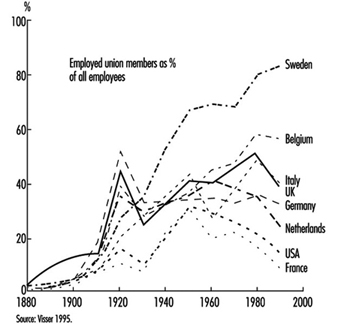

Trade Unions

The classic definition of a trade union is “a continuous association of wage earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment” (Webb and Webb 1920). The origins of trade unions go back as far as the first attempts to organize collective action at the beginning of the industrial revolution. In the modern sense, however, trade unions arose in the later part of the nineteenth century, when governments first began to concede the unions’ legal right to exist (previously, they had been seen as illegal combinations interfering with freedom of commerce, or as outlawed political groups). Trade unions reflect the conviction that only by banding together can workers improve their situation. Trade union rights were born out of economic and political struggle which saw short-term individual sacrifice in the cause of longer-term collective gain. They have often played an important role in national politics and have influenced developments in the world of work at the regional and international levels. Having suffered membership losses, however, in recent years in a number of countries (in North America and some parts of Europe), their role is under challenge in many quarters (see figure 2). The pattern is mixed with areas of membership growth in the public service in many countries around the world and with a new lease on life in places where trade unions were previously non-existent or active only under severe restrictions (e.g., Korea, the Philippines, some countries of Central and Eastern Europe). The flourishing of democratic institutions goes hand in hand with the exercise of trade union freedoms, as the cases of Chile and Poland in the 1980s and 1990s best illustrate. A process of internal reform and reorientation to attract greater and more diverse membership, particularly more women, can also be seen within trade union circles in a number of countries. Only time will tell if these and other factors will be sufficient to deflect the counterweighing tendencies towards the “de-collectivization”, also referred to as “atomization”, of labour relations that has accompanied increased economic globalization and ideological individualism.

Figure 2. Membership rates in trade unions, 1980-1990

In contemporary industrial relations systems, the functions fulfilled by trade unions are, like employers’ organizations, basically the following: defence and promotion of the members’ interests; political representation; and provision of services to members. The flip side of trade unions’ representative function is their control function: their legitimacy depends in part upon the ability to exert discipline over the membership, as for example in calling or ending a strike. The trade unions’ constant challenge is to increase their density, that is, the number of members as a percentage of the formal sector workforce. The members of trade unions are individuals; their dues, called contributions in some systems, support the union’s activities. (Trade unions financed by employers, called “company unions”, or by governments as in formerly Communist countries, are not considered here, since only independent organizations of workers are true trade unions.) Affiliation is generally a matter of an individual’s voluntary decision, although some unions that have been able to win closed shop or union security arrangements are considered to be the representatives of all workers covered by a particular collective bargaining agreement (i.e., in countries where trade unions are recognized as representatives of workers in a circumscribed bargaining unit). Trade unions may be affiliated to umbrella organizations at the industrial, national, regional and international levels.

Trade unions are structured along various lines: by craft or occupation, by branch of industry, by whether they group white- or blue-collar workers and sometimes even by enterprise. There are also general unions, which include workers from various occupations and industries. Even in countries where mergers of industrial unions and general unions are the trend, the situation of agricultural or rural workers has often favoured the development of special structures for that sector. On top of this breakdown there is often a territorial division, with regional and sometimes local subunits, within a union. In some countries there have been splits in the labour movement around ideological (party politics) and even religious lines which then come to be reflected in trade union structure and membership. Public sector employees tend to be represented by unions separate from those representing employees in the private sector, although there are exceptions to this as well.

The legal status of a trade union may be that of any other association, or it may be subject to special rules. A great number of countries require trade unions to register and to divulge certain basic information to the authorities (name, address, identity of officials, etc.). In some countries this goes beyond mere record-keeping to interference; in extreme cases of disregard for freedom of association principles, trade unions will need government authorization to operate. As representatives of workers, trade unions are empowered to enter into engagements on their behalf. Some countries (such as the United States) require employer recognition of trade unions as an initial prerequisite to engaging in collective bargaining.

Trade union density varies widely between and within countries. In some countries in Western Europe, for instance, it is very high in the public sector but tends to be low in the private sector and especially in its white-collar employment. The figures for blue-collar employment in that region are mixed, from a high in Austria and Sweden to a low in France, where, however, trade union political power far exceeds what membership figures would suggest. There is some positive correlation between centralization of bargaining and trade union density, but exceptions to this also exist.

As voluntary associations, trade unions draw up their own rules, usually in the form of a constitution and by-laws. In democratic trade union structures, members select trade union officers either by direct vote or through delegates to a general conference. Internal union government in a small, highly decentralized union of workers in a particular occupational group is likely to differ significantly from that found in a large, centralized general or industrial union. There are tasks to allocate among union officers, between paid and unpaid union representatives and coordination work to be done. The financial resources available to a union will also vary depending upon its size and the ease with which it can collect dues. Institution of a dues check-off system (whereby dues are deducted from a worker’s wages and paid directly to the union) alleviates this task greatly. In most of Central and Eastern Europe, trade unions that were dominated and funded by the state are being transformed and/or joined by new independent organizations; all are struggling to find a place and operate successfully in the new economic structure. Extremely low wages (and thus dues) there and in developing countries with government-supported unions make it difficult to build a strong independent union movement.

In addition to the important function of collective bargaining, one of the main activities of trade unions in many countries is their political work. This may take the form of direct representation, with trade unions being given reserved seats in some parliaments (e.g., Senegal) and on tripartite bodies that have a role in determining national economic and social policy (e.g., Austria, France, the Netherlands), or on tripartite advisory bodies in the fields of labour and social affairs (e.g., in many Latin American and some African and Asian countries). In the European Union, trade union federations have had an important impact on the development of social policy. More typically, trade unions have an influence through the exercise of power (backed up by a threat of industrial action) and lobbying political decision makers at the national level. It is certainly true that trade unions have successfully fought for greater legislative protection for all workers around the world; some believe that this has been a bittersweet victory, in the long run undermining their own justification to exist. The objectives and issues of union political action have often extended well beyond narrower interests; a prime example of this was the struggle against apartheid within South Africa and the international solidarity expressed by unions around the world in words and in deeds (e.g., organizing dockworker boycotts of imported South African coal). Whether trade union political activity is on the offence or the defence will of course depend largely on whether the government in power tends to be pro- or anti-labour. It will also depend upon the union’s relationship to political parties; some unions, particularly in Africa, were part of their countries’ struggles for independence and maintain very close ties with ruling political parties. In other countries there is a traditional interdependence between the labour movement and a political party (e.g., Australia, United Kingdom), whereas in others alliances may shift over time. In any event, the power of trade unions often exceeds what would be expected from their numerical strength, particularly where they represent workers in a key economic or public service sector, such as transport or mining.

Aside from trade unions, many other types of workers’ participation have sprung up to provide indirect or direct representation of employees. In some instances they exist alongside trade unions; in others they are the only type of participation available to workers. The functions and powers of workers’ representatives that exist under such arrangements are described in the article “Forms of workers’ participation’’.

The third type of function of trade unions, providing services to members, focuses first and foremost on the workplace. A shop steward at the enterprise level is there to ensure that workers’ rights under the collective bargaining agreement and the law are being respected–and, if not, to take action. The union officer’s job is to defend the interests of workers vis-à-vis management, thereby legitimizing his or her own representative role. This may involve taking up an individual grievance over discipline or dismissal, or cooperating with management on a joint health and safety committee. Outside the workplace, many unions provide other types of benefit, such as preferential access to credit and participation in welfare schemes. The union hall can also serve as a centre for cultural events or even large family ceremonies. The range of services a union can offer to its members is vast and reflects the creativity and resources of the union itself as well as the cultural milieu in which it operates.

As Visser observes:

The power of trade unions depends on various internal and external factors. We can distinguish between organizational power (how many internal sources of power can unions mobilize?), institutional power (which external sources of support can unions depend on?) and economic power (which market forces play into the hands of unions?) (Visser in van Ruysseveldt et al. 1995).

Among the factors he identifies for a strong trade union structure are the mobilization of a large, stable, dues-paying and well-trained membership (to this could be added a membership that reflects the composition of the labour market), avoidance of organizational fragmentation and political or ideological rifts and development of an organizational structure that provides a presence at the company level while having central control of funds and decision making. Whether such a model for success, which to date has been national in character, can evolve in the face of an increasingly internationalized economy, is the great challenge facing trade unions at this juncture.