This article is adapted from the 3rd edition of the Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety.

Anthropometry is a fundamental branch of physical anthropology. It represents the quantitative aspect. A wide system of theories and practice is devoted to defining methods and variables to relate the aims in the different fields of application. In the fields of occupational health, safety and ergonomics anthropometric systems are mainly concerned with body build, composition and constitution, and with the dimensions of the human body’s interrelation to workplace dimensions, machines, the industrial environment, and clothing.

Anthropometric variables

An anthropometric variable is a measurable characteristic of the body that can be defined, standardized and referred to a unit of measurement. Linear variables are generally defined by landmarks that can be precisely traced to the body. Landmarks are generally of two types: skeletal-anatomical, which may be found and traced by feeling bony prominences through the skin, and virtual landmarks that are simply found as maximum or minimum distances using the branches of a caliper.

Anthropometric variables have both genetic and environmental components and may be used to define individual and population variability. The choice of variables must be related to the specific research purpose and standardized with other research in the same field, as the number of variables described in the literature is extremely large, up to 2,200 having been described for the human body.

Anthropometric variables are mainly linear measures, such as heights, distances from landmarks with subject standing or seated in standardized posture; diameters, such as distances between bilateral landmarks; lengths, such as distances between two different landmarks; curved measures, namely arcs, such as distances on the body surface between two landmarks; and girths, such as closed all-around measures on body surfaces, generally positioned at at least one landmark or at a defined height.

Other variables may require special methods and instruments. For instance skinfold thickness is measured by means of special constant pressure calipers. Volumes are measured by calculation or by immersion in water. To obtain full information on body surface characteristics, a computer matrix of surface points may be plotted using biostereometric techniques.

Instruments

Although sophisticated anthropometric instruments have been described and used with a view to automated data collection, basic anthropometric instruments are quite simple and easy to use. Much care must be taken to avoid common errors resulting from misinterpretation of landmarks and incorrect postures of subjects.

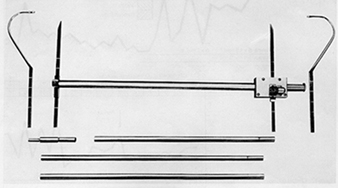

The standard anthropometric instrument is the anthropometer—a rigid rod 2 metres long, with two counter-reading scales, with which vertical body dimensions, such as heights of landmarks from floor or seat, and transverse dimensions, such as diameters, can be taken.

Commonly the rod can be split into 3 or 4 sections which fit into one another. A sliding branch with a straight or curved claw makes it possible to measure distances from the floor for heights, or from a fixed branch for diameters. More elaborate anthropometers have a single scale for heights and diameters to avoid scale errors, or are fitted with digital mechanical or electronic reading devices (figure 1).

A stadiometer is a fixed anthropometer, generally used only for stature and frequently associated with a weight beam scale.

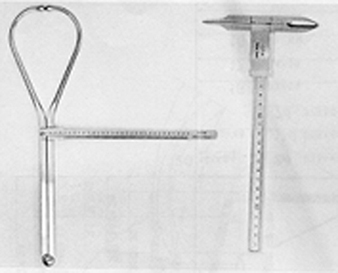

For transverse diameters a series of calipers may be used: the pelvimeter for measures up to 600 mm and the cephalometer up to 300 mm. The latter is particularly suitable for head measurements when used together with a sliding compass (figure 2).

Figure 2. A cephalometer together with a sliding compass

The foot-board is used for measuring the feet and the head-board provides cartesian co-ordinates of the head when oriented in the “Frankfort plane” (a horizontal plane passing through porion and orbitale landmarks of the head).The hand may be measured with a caliper, or with a special device composed of five sliding rulers.

Skinfold thickness is measured with a constant-pressure skinfold caliper generally with a pressure of 9.81 x 104 Pa (the pressure imposed by a weight of 10 g on an area of 1 mm2).

For arcs and girths a narrow, flexible steel tape with flat section is used. Self-straightening steel tapes must be avoided.

Systems of variables

A system of anthropometric variables is a coherent set of body measurements to solve some specific problems.

In the field of ergonomics and safety, the main problem is fitting equipment and workspace to humans and tailoring clothes to the right size.

Equipment and workspace require mainly linear measures of limbs and body segments that can easily be calculated from landmark heights and diameters, whereas tailoring sizes are based mainly on arcs, girths and flexible tape lengths. Both systems may be combined according to need.

In any case, it is absolutely necessary to have a precise space reference for each measurement. The landmarks must, therefore, be linked by heights and diameters and every arc or girth must have a defined landmark reference. Heights and slopes must be indicated.

In a particular survey, the number of variables has to be limited to the minimum so as to avoid undue stress on the subject and operator.

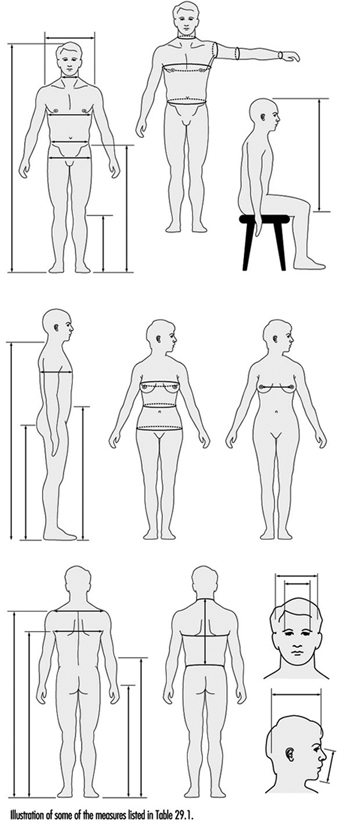

A basic set of variables for workspace has been reduced to 33 measured variables (figure 3) plus 20 derived by a simple calculation. For a general-purpose military survey, Hertzberg and co-workers use 146 variables. For clothes and general biological purposes the Italian Fashion Board (Ente Italiano della Moda) uses a set of 32 general purpose variables and 28 technical ones. The German norm (DIN 61 516) of control body dimensions for clothes includes 12 variables. The recommendation of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) for anthropometry includes a core list of 36 variables (see table 1). The International Data on Anthropometry tables published by the ILO list 19 body dimensions for the populations of 20 different regions of the world (Jürgens, Aune and Pieper 1990).

Figure 3. Basic set of anthropometric variables

Table 1. Basic anthropometric core list

1.1 Forward reach (to hand grip with subject standing upright against a wall)

1.2 Stature (vertical distance from floor to head vertex)

1.3 Eye height (from floor to inner eye corner)

1.4 Shoulder height (from floor to acromion)

1.5 Elbow height (from floor to radial depression of elbow)

1.6 Crotch height (from floor to pubic bone)

1.7 Finger tip height (from floor to grip axis of fist)

1.8 Shoulder breadth (biacromial diameter)

1.9 Hip breadth, standing (the maximum distance across hips)

2.1 Sitting height (from seat to head vertex)

2.2 Eye height, sitting (from seat to inner corner of the eye)

2.3 Shoulder height, sitting (from seat to acromion)

2.4 Elbow height, sitting (from seat to lowest point of bent elbow)

2.5 Knee height (from foot-rest to the upper surface of thigh)

2.6 Lower leg length (height of sitting surface)

2.7 Forearm-hand length (from back of bent elbow to grip axis)

2.8 Body depth, sitting (seat depth)

2.9 Buttock-knee length (from knee-cap to rearmost point of buttock)

2.10 Elbow to elbow breadth (distance between lateral surface of the elbows)

2.11 Hip breadth, sitting (seat breadth)

3.1 Index finger breadth, proximal (at the joint between medial and proximal phalanges)

3.2 Index finger breadth, distal (at the joint between distal and medial phalanges)

3.3 Index finger length

3.4 Hand length (from tip of middle finger to styloid)

3.5 Handbreadth (at metacarpals)

3.6 Wrist circumference

4.1 Foot breadth

4.2 Foot length

5.1 Heat circumference (at glabella)

5.2 Sagittal arc (from glabella to inion)

5.3 Head length (from glabella to opisthocranion)

5.4 Head breadth (maximum above the ear)

5.5 Bitragion arc (over the head between the ears)

6.1 Waist circumference (at the umbilicus)

6.2 Tibial height (from the floor to the highest point on the antero-medial margin of the glenoid of the tibia)

6.3 Cervical height sitting (to the tip of the spinous process of the 7th cervical vertebra).

Source: Adapted from ISO/DP 7250 1980).

Precision and errors

The precision of living body dimensions must be considered in a stochastic manner because the human body is highly unpredictable, both as a static and as a dynamic structure.

A single individual may grow or change in muscularity and fatness; undergo skeletal changes as a consequence of aging, disease or accidents; or modify behavior or posture. Different subjects differ by proportions, not only by general dimensions. Tall stature subjects are not mere enlargements of short ones; constitutional types and somatotypes probably vary more than general dimensions.

The use of mannequins, particularly those representing the standard 5th, 50th and 95th percentiles for fitting trials may be highly misleading, if body variations in body proportions are not taken into consideration.

Errors result from misinterpretation of landmarks and incorrect use of instruments (personal error), imprecise or inexact instruments (instrumental error), or changes in subject posture (subject error—this latter may be due to difficulties of communication if the cultural or linguistic background of the subject differs from that of the operator).

Statistical treatment

Anthropometric data must be treated by statistical procedures, mainly in the field of inference methods applying univariate (mean, mode, percentiles, histograms, variance analysis, etc.), bivariate (correlation, regression) and multivariate (multiple correlation and regression, factor analysis, etc.) methods. Various graphical methods based on statistical applications have been devised to classify human types (anthropometrograms, morphosomatograms).

Sampling and survey

As anthropometric data cannot be collected for the whole population (except in the rare case of a particularly small population), sampling is generally necessary. A basically random sample should be the starting point of any anthropometric survey. To keep the number of measured subjects to a reasonable level it is generally necessary to have recourse to multiple-stage stratified sampling. This allows the most homogeneous subdivision of the population into a number of classes or strata.

The population may be subdivided by sex, age group, geographical area, social variables, physical activity and so on.

Survey forms have to be designed keeping in mind both measuring procedure and data treatment. An accurate ergonomic study of the measuring procedure should be made in order to reduce the operator’s fatigue and possible errors. For this reason, variables must be grouped according to the instrument used and ordered in sequence so as to reduce the number of body flexions the operator has to make.

To reduce the effect of personal error, the survey should be carried out by one operator. If more than one operator has to be used, training is necessary to assure the replicability of measurements.

Population anthropometrics

Disregarding the highly criticized concept of “race”, human populations are nevertheless highly variable in size of individuals and in size distribution. Generally human populations are not strictly Mendelian; they are commonly the result of admixture. Sometimes two or more populations, with different origins and adaptation, live together in the same area without interbreeding. This complicates the theoretical distribution of traits. From the anthropometric viewpoint, sexes are different populations. Populations of employees may not correspond exactly to the biological population of the same area as a consequence of possible aptitudinal selection or auto-selection due to job choice.

Populations from different areas may differ as a consequence of different adaptation conditions or biological and genetic structures.

When close fitting is important a survey on a random sample is necessary.

Fitting trials and regulation

The adaptation of workspace or equipment to the user may depend not only on the bodily dimensions, but also on such variables as tolerance of discomfort and nature of activities, clothing, tools and environmental conditions. A combination of a checklist of relevant factors, a simulator and a series of fitting trials using a sample of subjects chosen to represent the range of body sizes of the expected user population can be used.

The aim is to find tolerance ranges for all subjects. If the ranges overlap it is possible to select a narrower final range that is not outside the tolerance limits of any subject. If there is no overlap it will be necessary to make the structure adjustable or to provide it in different sizes. If more than two dimensions are adjustable a subject may not be able to decide which of the possible adjustments will fit him best.

Adjustability can be a complicated matter, especially when uncomfortable postures result in fatigue. Precise indications must, therefore, be given to the user who frequently knows little or nothing about his own anthropometric characteristics. In general, an accurate design should reduce the need for adjustment to the minimum. In any case, it should constantly be kept in mind what is involved is anthropometrics, not merely engineering.

Dynamic anthropometrics

Static anthropometrics may give wide information about movement if an adequate set of variables has been chosen. Nevertheless, when movements are complicated and a close fit with the industrial environment is desirable, as in most user-machine and human-vehicle interfaces, an exact survey of postures and movements is necessary. This may be done with suitable mock-ups that allow tracing of reach lines or by photography. In this case, a camera fitted with a telephoto lens and an anthropometric rod, placed in the sagittal plane of the subject, allows standardized photographs with little distortion of the image. Small labels on subjects’ articulations make the exact tracing of movements possible.

Another way of studying movements is to formalize postural changes according to a series of horizontal and vertical planes passing through the articulations. Again, using computerized human models with computer-aided design (CAD) systems is a feasible way to include dynamic anthropometrics in ergonomic workplace design.