Muscular Work in Occupational Activities

In industrialized countries around 20% of workers are still employed in jobs requiring muscular effort (Rutenfranz et al. 1990). The number of conventional heavy physical jobs has decreased, but, on the other hand, many jobs have become more static, asymmetrical and stationary. In developing countries, muscular work of all forms is still very common.

Muscular work in occupational activities can be roughly divided into four groups: heavy dynamic muscle work, manual materials handling, static work and repetitive work. Heavy dynamic work tasks are found in forestry, agriculture and the construction industry, for example. Materials handling is common, for example, in nursing, transportation and warehousing, while static loads exist in office work, the electronics industry and in repair and maintenance tasks. Repetitive work tasks can be found in the food and wood-processing industries, for example.

It is important to note that manual materials handling and repetitive work are basically either dynamic or static muscular work, or a combination of these two.

Physiology of Muscular Work

Dynamic muscular work

In dynamic work, active skeletal muscles contract and relax rhythmically. The blood flow to the muscles is increased to match metabolic needs. The increased blood flow is achieved through increased pumping of the heart (cardiac output), decreased blood flow to inactive areas, such as kidneys and liver, and increased number of open blood vessels in the working musculature. Heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen extraction in the muscles increase linearly in relation to working intensity. Also, pulmonary ventilation is heightened owing to deeper breathing and increased breathing frequency. The purpose of activating the whole cardio-respiratory system is to enhance oxygen delivery to the active muscles. The level of oxygen consumption measured during heavy dynamic muscle work indicates the intensity of the work. The maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) indicates the person’s maximum capacity for aerobic work. Oxygen consumption values can be translated to energy expenditure (1 litre of oxygen consumption per minute corresponds to approximately 5 kcal/min or 21 kJ/min).

In the case of dynamic work, when the active muscle mass is smaller (as in the arms), maximum working capacity and peak oxygen consumption are smaller than in dynamic work with large muscles. At the same external work output, dynamic work with small muscles elicits higher cardio-respiratory responses (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure) than work with large muscles (figure 1).

Figure 1. Static versus dynamic work

Static muscle work

In static work, muscle contraction does not produce visible movement, as, for example, in a limb. Static work increases the pressure inside the muscle, which together with the mechanical compression occludes blood circulation partially or totally. The delivery of nutrients and oxygen to the muscle and the removal of metabolic end-products from the muscle are hampered. Thus, in static work, muscles become fatigued more easily than in dynamic work.

The most prominent circulatory feature of static work is a rise in blood pressure. Heart rate and cardiac output do not change much. Above a certain intensity of effort, blood pressure increases in direct relation to the intensity and the duration of the effort. Furthermore, at the same relative intensity of effort, static work with large muscle groups produces a greater blood pressure response than does work with smaller muscles. (See figure 2)

Figure 2. The expanded stress-strain model modified from Rohmert (1984)

In principle, the regulation of ventilation and circulation in static work is similar to that in dynamic work, but the metabolic signals from the muscles are stronger, and induce a different response pattern.

Consequences of Muscular Overload in Occupational Activities

The degree of physical strain a worker experiences in muscular work depends on the size of the working muscle mass, the type of muscular contractions (static, dynamic), the intensity of contractions, and individual characteristics.

When muscular workload does not exceed the worker’s physical capacities, the body will adapt to the load and recovery is quick when the work is stopped. If the muscular load is too high, fatigue will ensue, working capacity is reduced, and recovery slows down. Peak loads or prolonged overload may result in organ damage (in the form of occupational or work-related diseases). On the other hand, muscular work of certain intensity, frequency, and duration may also result in training effects, as, on the other hand, excessively low muscular demands may cause detraining effects. These relationships are represented by the so-called expanded stress-strain concept developed by Rohmert (1984) (figure 3).

Figure 3. Analysis of acceptable workloads

In general, there is little epidemiological evidence that muscular overload is a risk factor for diseases. However, poor health, disability and subjective overload at work converge in physically demanding jobs, especially with older workers. Furthermore, many risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal diseases are connected to different aspects of muscular workload, such as the exertion of strength, poor working postures, lifting and sudden peak loads.

One of the aims of ergonomics has been to determine acceptable limits for muscular workloads which could be applied for the prevention of fatigue and disorders. Whereas the prevention of chronic effects is the focus of epidemiology, work physiology deals mostly with short-term effects, that is, fatigue in work tasks or during a work day.

Acceptable Workload in Heavy Dynamic Muscular Work

The assessment of acceptable workload in dynamic work tasks has traditionally been based on measurements of oxygen consumption (or, correspondingly, energy expenditure). Oxygen consumption can be measured with relative ease in the field with portable devices (e.g., Douglas bag, Max Planck respirometer, Oxylog, Cosmed), or it can be estimated from heart rate recordings, which can be made reliably at the workplace, for example, with the SportTester device. The use of heart rate in the estimation of oxygen consumption requires that it be individually calibrated against measured oxygen consumption in a standard work mode in the laboratory, i.e., the investigator must know the oxygen consumption of the individual subject at a given heart rate. Heart rate recordings should be treated with caution because they are also affected by such factors as physical fitness, environmental temperature, psychological factors and size of active muscle mass. Thus, heart rate measurements can lead to overestimates of oxygen consumption in the same way that oxygen consumption values can give rise to underestimates of global physiological strain by reflecting only energy requirements.

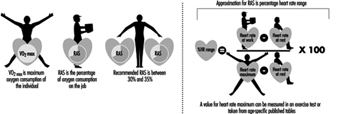

Relative aerobic strain (RAS) is defined as the fraction (expressed as a percentage) of a worker’s oxygen consumption measured on the job relative to his or her VO2max measured in the laboratory. If only heart rate measurements are available, a close approximation to RAS can be made by calculating a value for percentage heart rate range (% HR range) with the so-called Karvonen formula as in figure 3.

VO2max is usually measured on a bicycle ergometer or treadmill, for which the mechanical efficiency is high (20-25%). When the active muscle mass is smaller or the static component is higher, VO2max and mechanical efficiency will be smaller than in the case of exercise with large muscle groups. For example, it has been found that in the sorting of postal parcels the VO2max of workers was only 65% of the maximum measured on a bicycle ergometer, and the mechanical efficiency of the task was less than 1%. When guidelines are based on oxygen consumption, the test mode in the maximal test should be as close as possible to the real task. This goal, however, is difficult to achieve.

According to Åstrand’s (1960) classical study, RAS should not exceed 50% during an eight-hour working day. In her experiments, at a 50% workload, body weight decreased, heart rate did not reach steady state and subjective discomfort increased during the day. She recommended a 50% RAS limit for both men and women. Later on she found that construction workers spontaneously chose an average RAS level of 40% (range 25-55%) during a working day. Several more recent studies have indicated that the acceptable RAS is lower than 50%. Most authors recommend 30-35% as an acceptable RAS level for the entire working day.

Originally, the acceptable RAS levels were developed for pure dynamic muscle work, which rarely occurs in real working life. It may happen that acceptable RAS levels are not exceeded, for example, in a lifting task, but the local load on the back may greatly exceed acceptable levels. Despite its limitations, RAS determination has been widely used in the assessment of physical strain in different jobs.

In addition to the measurement or estimation of oxygen consumption, other useful physiological field methods are also available for the quantification of physical stress or strain in heavy dynamic work. Observational techniques can be used in the estimation of energy expenditure (e.g., with the aid of the Edholm scale) (Edholm 1966). Rating of perceived exertion (RPE) indicates the subjective accumulation of fatigue. New ambulatory blood pressure monitoring systems allow more detailed analyses of circulatory responses.

Acceptable Workload in Manual Materials Handling

Manual materials handling includes such work tasks as lifting, carrying, pushing and pulling of various external loads. Most of the research in this area has focused on low back problems in lifting tasks, especially from the biomechanical point of view.

A RAS level of 20-35% has been recommended for lifting tasks, when the task is compared to an individual maximum oxygen consumption obtained from a bicycle ergometer test.

Recommendations for a maximum permissible heart rate are either absolute or related to the resting heart rate. The absolute values for men and women are 90-112 beats per minute in continuous manual materials handling. These values are about the same as the recommended values for the increase in heart rate above resting levels, that is, 30 to 35 beats per minute. These recommendations are also valid for heavy dynamic muscle work for young and healthy men and women. However, as mentioned previously, heart rate data should be treated with caution, because it is also affected by other factors than muscle work.

The guidelines for acceptable workload for manual materials handling based on biomechanical analyses comprise several factors, such as weight of the load, handling frequency, lifting height, distance of the load from the body and physical characteristics of the person.

In one large-scale field study (Louhevaara, Hakola and Ollila 1990) it was found that healthy male workers could handle postal parcels weighing 4 to 5 kilograms during a shift without any signs of objective or subjective fatigue. Most of the handling occurred below shoulder level, the average handling frequency was less than 8 parcels per minute and the total number of parcels was less than 1,500 per shift. The mean heart rate of the workers was 101 beats per minute and their mean oxygen consumption 1.0 l/min, which corresponded to 31% RAS as related to bicycle maximum.

Observations of working postures and use of force carried out for example according to OWAS method (Karhu, Kansi and Kuorinka 1977), ratings of perceived exertion and ambulatory blood pressure recordings are also suitable methods for stress and strain assessments in manual materials handling. Electromyography can be used to assess local strain responses, for example in arm and back muscles.

Acceptable Workload for Static Muscular Work

Static muscular work is required chiefly in maintaining working postures. The endurance time of static contraction is exponentially dependent on the relative force of contraction. This means, for example, that when the static contraction requires 20% of the maximum force, the endurance time is 5 to 7 minutes, and when the relative force is 50%, the endurance time is about 1 minute.

Older studies indicated that no fatigue will be developed when the relative force is below 15% of the maximum force. However, more recent studies have indicated that the acceptable relative force is specific to the muscle or muscle group, and is 2 to 5% of the maximum static strength. These force limits are, however, difficult to use in practical work situations because they require electromyographic recordings.

For the practitioner, fewer field methods are available for the quantification of strain in static work. Some observational methods (e.g., the OWAS method) exist to analyse the proportion of poor working postures, that is, postures deviating from normal middle positions of the main joints. Blood pressure measurements and ratings of perceived exertion may be useful, whereas heart rate is not so applicable.

Acceptable Workload in Repetitive Work

Repetitive work with small muscle groups resembles static muscle work from the point of view of circulatory and metabolic responses. Typically, in repetitive work muscles contract over 30 times per minute. When the relative force of contraction exceeds 10% of the maximum force, endurance time and muscle force start to decrease. However, there is wide individual variation in endurance times. For example, the endurance time varies between two to fifty minutes when the muscle contracts 90 to 110 times per minute at a relative force level of 10 to 20% (Laurig 1974).

It is very difficult to set any definitive criteria for repetitive work, because even very light levels of work (as with the use of a microcomputer mouse) may cause increases in intramuscular pressure, which may sometimes lead to swelling of muscle fibres, pain and reduction in muscle strength.

Repetitive and static muscle work will cause fatigue and reduced work capacity at very low relative force levels. Therefore, ergonomic interventions should aim to minimize the number of repetitive movements and static contractions as far as possible. Very few field methods are available for strain assessment in repetitive work.

Prevention of Muscular Overload

Relatively little epidemiological evidence exists to show that muscular load is harmful to health. However, work physiological and ergonomic studies indicate that muscular overload results in fatigue (i.e., decrease in work capacity) and may reduce productivity and quality of work.

The prevention of muscular overload may be directed to the work content, the work environment and the worker. The load can be adjusted by technical means, which focus on the work environment, tools, and/or the working methods. The fastest way to regulate muscular workload is to increase the flexibility of working time on an individual basis. This means designing work-rest regimens which take into account the workload and the needs and capacities of the individual worker.

Static and repetitive muscular work should be kept at a minimum. Occasional heavy dynamic work phases may be useful for the maintenance of endurance type physical fitness. Probably, the most useful form of physical activity that can be incorporated into a working day is brisk walking or stair climbing.

Prevention of muscular overload, however, is very difficult if a worker’s physical fitness or working skills are poor. Appropriate training will improve working skills and may reduce muscular loads at work. Also, regular physical exercise during work or leisure time will increase the muscular and cardio-respiratory capacities of the worker.