Virtually all of medicine is devoted to either preventing cell death, in diseases such as myocardial infarction, stroke, trauma and shock, or causing it, as in the case of infectious diseases and cancer. It is, therefore, essential to understand the nature and mechanisms involved. Cell death has been classified as “accidental”, that is, caused by toxic agents, ischaemia and so on, or “programmed”, as occurs during embryological development, including formation of digits, and resorption of the tadpole tail.

Cell injury and cell death are, therefore, important both in physiology and in pathophysiology. Physiological cell death is extremely important during embryogenesis and embryonic development. The study of cell death during development has led to important and new information on the molecular genetics involved, especially through the study of development in invertebrate animals. In these animals, the precise location and the significance of cells that are destined to undergo cell death have been carefully studied and, with the use of classic mutagenesis techniques, several involved genes have now been identified. In adult organs, the balance between cell death and cell proliferation controls organ size. In some organs, such as the skin and the intestine, there is a continual turnover of cells. In the skin, for example, cells differentiate as they reach the surface, and finally undergo terminal differentiation and cell death as keratinization proceeds with the formation of crosslinked envelopes.

Many classes of toxic chemicals are capable of inducing acute cell injury followed by death. These include anoxia and ischaemia and their chemical analogues such as potassium cyanide; chemical carcinogens, which form electrophiles that covalently bind to proteins in nucleic acids; oxidant chemicals, resulting in free radical formation and oxidant injury; activation of complement; and a variety of calcium ionophores. Cell death is also an important component of chemical carcinogenesis; many complete chemical carcinogens, at carcinogenic doses, produce acute necrosis and inflammation followed by regeneration and preneoplasia.

Definitions

Cell injury

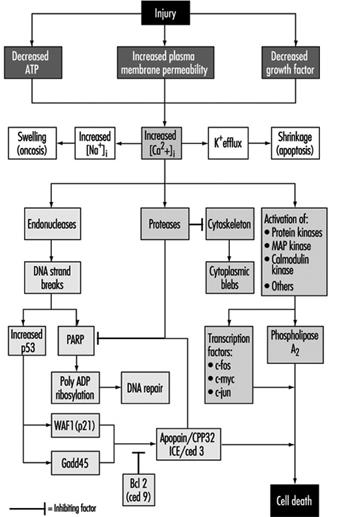

Cell injury is defined as an event or stimulus, such as a toxic chemical, that perturbs the normal homeostasis of the cell, thus causing a number of events to occur (figure 1). The principal targets of lethal injury illustrated are inhibition of ATP synthesis, disruption of plasma membrane integrity or withdrawal of essential growth factors.

Lethal injuries result in the death of a cell after a variable period of time, depending on temperature, cell type and the stimulus; or they can be sublethal or chronic—that is, the injury results in an altered homeostatic state which, though abnormal, does not result in cell death (Trump and Arstila 1971; Trump and Berezesky 1992; Trump and Berezesky 1995; Trump, Berezesky and Osornio-Vargas 1981). In the case of a lethal injury, there is a phase prior to the time of cell death

during this time, the cell will recover; however, after a particular point in time (the “point of no return” or point of cell death), the removal of the injury does not result in recovery but instead the cell undergoes degradation and hydrolysis, ultimately reaching physical-chemical equilibrium with the environment. This is the phase known as necrosis. During the prelethal phase, several principal types of change occur, depending on the cell and the type of injury. These are known as apoptosis and oncosis.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is derived from the Greek words apo, meaning away from, and ptosis, meaning to fall. The term falling away from is derived from the fact that, during this type of prelethal change, the cells shrink and undergo marked blebbing at the periphery. The blebs then detach and float away. Apoptosis occurs in a variety of cell types following various types of toxic injury (Wyllie, Kerr and Currie 1980). It is especially prominent in lymphocytes, where it is the predominant mechanism for turnover of lymphocyte clones. The resulting fragments result in the basophilic bodies seen within macrophages in lymph nodes. In other organs, apoptosis typically occurs in single cells which are rapidly cleared away before and following death by phagocytosis of the fragments by adjacent parenchymal cells or by macrophages. Apoptosis occurring in single cells with subsequent phagocytosis typically does not result in inflammation. Prior to death, apoptotic cells show a very dense cytosol with normal or condensed mitochondria. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is normal or only slightly dilated. The nuclear chromatin is markedly clumped along the nuclear envelope and around the nucleolus. The nuclear contour is also irregular and nuclear fragmentation occurs. The chromatin conden- sation is associated with DNA fragmentation which, in many instances, occurs between nucleosomes, giving a characteristic ladder appearance on electrophoresis.

In apoptosis, increased [Ca2+]i may stimulate K+ efflux resulting in cell shrinkage, which probably requires ATP. Injuries that totally inhibit ATP synthesis, therefore, are more likely to result in apoptosis. A sustained increase of [Ca2+]i has a number of deleterious effects including activation of proteases, endonucleases, and phospholipases. Endonuclease activation results in single and double DNA strand breaks which, in turn, stimulate increased levels of p53 and in poly-ADP ribosylation, and of nuclear proteins which are essential in DNA repair. Activation of proteases modifies a number of substrates including actin and related proteins leading to bleb formation. Another important substrate is poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which inhibits DNA repair. Increased [Ca2+]i is also associated with activation of a number of protein kinases, such as MAP kinase, calmodulin kinase and others. Such kinases are involved in activation of transcription factors which initiate transcription of immediate-early genes, for example, c-fos, c-jun and c-myc, and in activation of phospholipase A2 which results in permeabilization of the plasma membrane and of intracellular membranes such as the inner membrane of mitochondria.

Oncosis

Oncosis, derived from the Greek word onkos, to swell, is so named because in this type of prelethal change the cell begins to swell almost immediately following the injury (Majno and Joris 1995). The reason for the swelling is an increase in cations in the water within the cell. The principal cation responsible is sodium, which is normally regulated to maintain cell volume. However, in the absence of ATP or if Na-ATPase of the plasmalemma is inhibited, volume control is lost because of intracellular protein, and sodium in the water continuing to increase. Among the early events in oncosis are, therefore, increased [Na+]i which leads to cellular swelling and increased [Ca2+]i resulting either from influx from the extracellular space or release from intracellular stores. This results in swelling of the cytosol, swelling of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, and the formation of watery blebs around the cell surface. The mitochondria initially undergo condensation, but later they too show high-amplitude swelling because of damage to the inner mitochondrial membrane. In this type of prelethal change, the chromatin undergoes condensation and ultimately degradation; however, the characteristic ladder pattern of apoptosis is not seen.

Necrosis

Necrosis refers to the series of changes that occur following cell death when the cell is converted to debris which is typically removed by the inflammatory response. Two types can be distinguished: oncotic necrosis and apoptotic necrosis. Oncotic necrosis typically occurs in large zones, for example, in a myocardial infarct or regionally in an organ after chemical toxicity, such as the renal proximal tubule following administration of HgCl2. Broad zones of an organ are involved and the necrotic cells rapidly incite an inflammatory reaction, first acute and then chronic. In the event that the organism survives, in many organs necrosis is followed by clearing away of the dead cells and regeneration, for example, in the liver or kidney following chemical toxicity. In contrast, apoptotic necrosis typically occurs on a single cell basis and the necrotic debris is formed within the phagocytes of macrophages or adjacent parenchymal cells. The earliest characteristics of necrotic cells include interruptions in plasma membrane continuity and the appearance of flocculent densities, representing denatured proteins within the mitochondrial matrix. In some forms of injury that do not initially interfere with mitochondrial calcium accumulation, calcium phosphate deposits can be seen within the mitochondria. Other membrane systems are similarly fragmenting, such as the ER, the lysosomes and the Golgi apparatus. Ultimately, the nuclear chromatin undergoes lysis, resulting from attack by lysosomal hydrolases. Following cell death, lysosomal hydrolases play an important part in clearing away debris with cathepsins, nucleolases and lipases since these have an acid pH optimum and can survive the low pH of necrotic cells while other cellular enzymes are denatured and inactivated.

Mechanisms

Initial stimulus

In the case of lethal injuries, the most common initial interactions resulting in injury leading to cell death are interference with energy metabolism, such as anoxia, ischaemia or inhibitors of respiration, and glycolysis such as potassium cyanide, carbon monoxide, iodo-acetate, and so on. As mentioned above, high doses of compounds that inhibit energy metabolism typically result in oncosis. The other common type of initial injury resulting in acute cell death is modification of the function of the plasma membrane (Trump and Arstila 1971; Trump, Berezesky and Osornio-Vargas 1981). This can either be direct damage and permeabilization, as in the case of trauma or activation of the C5b-C9 complex of complement, mechanical damage to the cell membrane or inhibition of the sodium-potassium (Na+-K+) pump with glycosides such as ouabain. Calcium ionophores such as ionomycin or A23187, which rapidly carry [Ca2+] down the gradient into the cell, also cause acute lethal injury. In some cases, the pattern in the prelethal change is apoptosis; in others, it is oncosis.

Signalling pathways

With many types of injury, mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation are rapidly affected. In some cells, this stimulates anaerobic glycolysis, which is capable of maintaining ATP, but with many injuries this is inhibited. The lack of ATP results in failure to energize a number of important homeostatic processes, in particular, control of intracellular ion homeostasis (Trump and Berezesky 1992; Trump, Berezesky and Osornio-Vargas 1981). This results in rapid increases of [Ca2+]i, and increased [Na+] and [Cl-] results in cell swelling. Increases in [Ca2+]i result in the activation of a number of other signalling mechanisms discussed below, including a series of kinases, which can result in increased immediate early gene transcription. Increased [Ca2+]i also modifies cytoskeletal function, in part resulting in bleb formation and in the activation of endonucleases, proteases and phospholipases. These seem to trigger many of the important effects discussed above, such as membrane damage through protease and lipase activation, direct degradation of DNA from endonuclease activation, and activation of kinases such as MAP kinase and calmodulin kinase, which act as transcription factors.

Through extensive work on development in the invertebrate C. elegans and Drosophila, as well as human and animal cells, a series of pro-death genes have been identified. Some of these invertebrate genes have been found to have mammalian counterparts. For example, the ced-3 gene, which is essential for programmed cell death in C. elegans, has protease activity and a strong homology with the mammalian interleukin converting enzyme (ICE). A closely related gene called apopain or prICE has recently been identified with even closer homology (Nicholson et al. 1995). In Drosophila, the reaper gene seems to be involved in a signal that leads to programmed cell death. Other pro-death genes include the Fas membrane protein and the important tumour-suppressor gene, p53, which is widely conserved. p53 is induced at the protein level following DNA damage and when phosphorylated acts as a transcription factor for other genes such as gadd45 and waf-1, which are involved in cell death signalling. Other immediate early genes such as c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc also seem to be involved in some systems.

At the same time, there are anti-death genes which appear to counteract the pro-death genes. The first of these to be identified was ced-9 from C. elegans, which is homologous to bcl-2 in humans. These genes act in an as yet unknown way to prevent cell killing by either genetic or chemical toxins. Some recent evidence indicates that bcl-2 may act as an antioxidant. Currently, there is much effort underway to develop an understanding of the genes involved and to develop ways to activate or inhibit these genes, depending on the situation.