Genetic toxicology, by definition, is the study of how chemical or physical agents affect the intricate process of heredity. Genotoxic chemicals are defined as compounds that are capable of modifying the hereditary material of living cells. The probability that a particular chemical will cause genetic damage inevitably depends on several variables, including the organism’s level of exposure to the chemical, the distribution and retention of the chemical once it enters the body, the efficiency of metabolic activation and/or detoxification systems in target tissues, and the reactivity of the chemical or its metabolites with critical macromolecules within cells. The probability that genetic damage will cause disease ultimately depends on the nature of the damage, the cell’s ability to repair or amplify genetic damage, the opportunity for expressing whatever alteration has been induced, and the ability of the body to recognize and suppress the multiplication of aberrant cells.

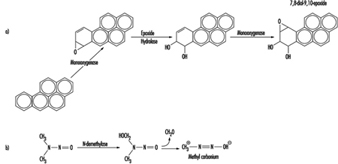

In higher organisms, hereditary information is organized in chromosomes. Chromosomes consist of tightly condensed strands of protein-associated DNA. Within a single chromosome, each DNA molecule exists as a pair of long, unbranched chains of nucleotide subunits linked together by phosphodiester bonds that join the 5 carbon of one deoxyribose moiety to the 3 carbon of the next (figure 1). In addition, one of four different nucleotide bases (adenine, cytosine, guanine or thymine) is attached to each deoxyribose subunit like beads on a string. Three-dimensionally, each pair of DNA strands forms a double helix with all of the bases oriented toward the inside of the spiral. Within the helix, each base is associated with its complementary base on the opposite DNA strand; hydrogen bonding dictates strong, noncovalent pairing of adenine with thymine and guanine with cytosine (figure 1). Since the sequence of nucleotide bases is complementary throughout the entire length of the duplex DNA molecule, both strands carry essentially the same genetic information. In fact, during DNA replication each strand serves as a template for the production of a new partner strand.

Figure 1. The (a) primary, (b) secondary and (c) tertiary organization of human hereditary information

Using RNA and an array of different proteins, the cell ultimately deciphers the information encoded by the linear sequence of bases within specific regions of DNA (genes) and produces proteins that are essential for basic cell survival as well as normal growth and differentiation. In essence, the nucleotides function like a biological alphabet which is used to code for amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

Using RNA and an array of different proteins, the cell ultimately deciphers the information encoded by the linear sequence of bases within specific regions of DNA (genes) and produces proteins that are essential for basic cell survival as well as normal growth and differentiation. In essence, the nucleotides function like a biological alphabet which is used to code for amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

When incorrect nucleotides are inserted or nucleotides are lost, or when unnecessary nucleotides are added during DNA synthesis, the mistake is called a mutation. It has been estimated that less than one mutation occurs for every 109 nucleotides incorporated during the normal replication of cells. Although mutations are not necessarily harmful, alterations causing inactivation or overexpression of important genes can result in a variety of disorders, including cancer, hereditary disease, developmental abnormalities, infertility and embryonic or perinatal death. Very rarely, a mutation can lead to enhanced survival; such occurrences are the basis of natural selection.

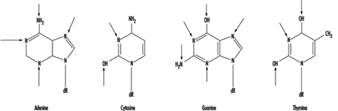

Although some chemicals react directly with DNA, most require metabolic activation. In the latter case, electrophilic intermediates such as epoxides or carbonium ions are ultimately responsible for inducing lesions at a variety of nucleophilic sites within the genetic material (figure 2). In other instances, genotoxicity is mediated by by-products of compound interaction with intracellular lipids, proteins, or oxygen.

Figure 2. Bioactivation of: a) benzo(a)pyrene; and b) N-nitrosodimethylamine

Because of their relative abundance in cells, proteins are the most frequent target of toxicant interaction. However, modification of DNA is of greater concern due to the central role of this molecule in regulating growth and differentiation through multiple generations of cells.

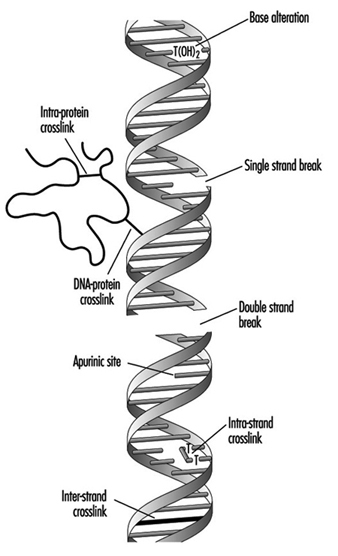

At the molecular level, electrophilic compounds tend to attack oxygen and nitrogen in DNA. The sites that are most prone to modification are illustrated in figure 3. Although oxygens within phosphate groups in the DNA backbone are also targets for chemical modification, damage to bases is thought to be biologically more relevant since these groups are considered to be the primary informational elements in the DNA molecule.

Figure 3. Primary sites of chemically-induced DNA damage

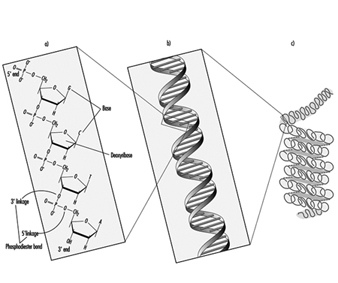

Compounds that contain one electrophilic moiety typically exert genotoxicity by producing mono-adducts in DNA. Similarly, compounds that contain two or more reactive moieties can react with two different nucleophilic centres and thereby produce intra- or inter-molecular crosslinks in genetic material (figure 4). Interstrand DNA-DNA and DNA-protein crosslinks can be particularly cytotoxic since they can form complete blocks to DNA replication. For obvious reasons, the death of a cell eliminates the possibility that it will be mutated or neoplastically transformed. Genotoxic agents can also act by inducing breaks in the phosphodiester backbone, or between bases and sugars (producing abasic sites) in DNA. Such breaks may be a direct result of chemical reactivity at the damage site, or may occur during the repair of one of the aforementioned types of DNA lesion.

Figure 4. Various types of damage to the protein-DNA complex

Over the past thirty to forty years, a variety of techniques have been developed to monitor the type of genetic damage induced by various chemicals. Such assays are described in detail elsewhere in this chapter and Encyclopaedia.

Misreplication of “microlesions” such as mono-adducts, abasic sites or single-strand breaks may ultimately result in nucleotide base-pair substitutions, or the insertion or deletion of short polynucleotide fragments in chromosomal DNA. In contrast, “macrolesions,” such as bulky adducts, crosslinks, or double-strand breaks may trigger the gain, loss or rearrangement of relatively large pieces of chromosomes. In any case, the consequences can be devastating to the organism since any one of these events can lead to cell death, loss of function or malignant transformation of cells. Exactly how DNA damage causes cancer is largely unknown. It is currently believed the process may involve inappropriate activation of proto-oncogenes such as myc and ras, and/or inactivation of recently identified tumour suppressor genes such as p53. Abnormal expression of either type of gene abrogates normal cellular mechanisms for controlling cell proliferation and/or differentiation.

The preponderance of experimental evidence indicates that the development of cancer following exposure to electrophilic compounds is a relatively rare event. This can be explained, in part, by the cell’s intrinsic ability to recognize and repair damaged DNA or the failure of cells with damaged DNA to survive. During repair, the damaged base, nucleotide or short stretch of nucleotides surrounding the damage site is removed and (using the opposite strand as a template) a new piece of DNA is synthesized and spliced into place. To be effective, DNA repair must occur with great accuracy prior to cell division, before opportunities for the propagation of mutation.

Clinical studies have shown that people with inherited defects in the ability to repair damaged DNA frequently develop cancer and/or developmental abnormalities at an early age (table 1). Such examples provide strong evidence linking accumulation of DNA damage to human disease. Similarly, agents that promote cell proliferation (such as tetradecanoylphorbol acetate) often enhance carcinogenesis. For these compounds, the increased likelihood of neoplastic transformation may be a direct consequence of a decrease in the time available for the cell to carry out adequate DNA repair.

Table 1. Hereditary, cancer-prone disorders that appear to involve defects in DNA repair

| Syndrome | Symptoms | Cellular phenotype |

| Ataxia telangiectasia | Neurological deterioration Immunodeficiency High incidence of lymphoma |

Hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation and certain alkylating agents. Dysregulated replication of damaged DNA (may indicate shortened time for DNA repair) |

| Bloom’s syndrome | Developmental abnormalities Lesions on exposed skin High incidence of tumours of the immune system and gastrointestinal tract |

High frequency of chromosomal aberrations Defective ligation of breaks associated with DNA repair |

| Fanconi’s anaemia | Growth retardation High incidence of leukaemia |

Hypersensitivity to crosslinking agents High frequency of chromosomal aberrations Defective repair of crosslinks in DNA |

| Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer | High incidence of colon cancer | Defect in DNA mismatch repair (when insertion of wrong nucleotide occurs during replication) |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum | High incidence of epithelioma on exposed areas of skin Neurological impairment (in many cases) |

Hypersensitivity to UV light and many chemical carcinogens Defects in excision repair and/or replication of damaged DNA |

The earliest theories on how chemicals interact with DNA can be traced back to studies conducted during the development of mustard gas for use in warfare. Further understanding grew out of efforts to identify anticancer agents that would selectively arrest the replication of rapidly dividing tumour cells. Increased public concern over hazards in our environment has prompted additional research into the mechanisms and consequences of chemical interaction with the genetic material. Examples of various types of chemicals which exert genotoxicity are presented in table 2.

Table 2. Examples of chemicals that exhibit genotoxicity in human cells

| Class of chemical | Example | Source of exposure | Probable genotoxic lesion |

| Aflatoxins | Aflatoxin B1 | Contaminated food | Bulky DNA adducts |

| Aromatic amines | 2-Acetylaminofluorene | Environmental | Bulky DNA adducts |

| Aziridine quinones | Mitomycin C | Cancer chemotherapy | Mono-adducts, interstrand crosslinks and single-strand breaks in DNA. |

| Chlorinated hydrocarbons | Vinyl chloride | Environmental | Mono-adducts in DNA |

| Metals and metal compounds | Cisplatin | Cancer chemotherapy | Both intra- and inter-strand crosslinks in DNA |

| Nickel compounds | Environmental | Mono-adducts and single-strand breaks in DNA | |

| Nitrogen mustards | Cyclophosphamide | Cancer chemotherapy | Mono-adducts and interstrand crosslinks in DNA |

| Nitrosamines | N-Nitrosodimethylamine | Contaminated food | Mono-adducts in DNA |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | Benzo(a)pyrene | Environmental | Bulky DNA adducts |