Introduction

Ergonomics standards can take many forms, such as regulations which are promulgated on a national level, or guidelines and standards instituted by international organizations. They play an important role in improving the usability of systems. Design and performance standards give managers confidence that the systems they buy will be capable of being used productively, efficiently, safely and comfortably. They also provide users with a benchmark by which to judge their own working conditions. In this article we focus on the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ergonomics standard 9241 (ISO 1992) because it provides important, internationally recognized, criteria for selecting or designing VDU equipment and systems. ISO carries out its work through a series of technical committees, one of which is ISO TC 159 SC4 Ergonomics of Human System Interaction Committee, which is responsible for ergonomics standards for situations in which human beings and technological systems interact. Its members are representatives of the national standards bodies of member countries and meetings involve national delegations in discussing and voting on resolutions and technical documents. The primary technical work of the committee takes place in eight Working Groups (WGs), each of which has responsibility for different work items listed in figure 1. This sub-committee has developed ISO 9241.

Figure 1. Technical Working Groups of the Ergonomics of Human System Interaction Technical Committee (ISO TC 159 SC4). ISO 9241: Five working groups broke down the “parts” of the standard to those listed below. This illustration shows the correspondence between the parts of the standard and the various aspects of the workstation with which they are concerned

The work of the ISO has major international importance. Leading manufacturers pay great heed to ISO specifications. Most producers of VDUs are international corporations. It is obvious that the best and most effective solutions to workplace design problems from the international manufacturers’ point of view should be agreed upon internationally. Many regional authorities, such as the European Standardization Organization (CEN) have adopted ISO standards wherever appropriate. The Vienna Agreement, signed by the ISO and CEN, is the official instrument which ensures effective collaboration between the two organizations. As different parts of ISO 9241 are approved and published as international standards, they are adopted as European standards and become part of EN 29241. Since CEN standards replace national standards in the European Union (EU) and the European Free Trade Agreement (EFTA) Member States, the significance of ISO standards in Europe has grown, and, in turn, has also increased pressure on the ISO to efficiently produce standards and guidelines for VDUs.

The work of the ISO has major international importance. Leading manufacturers pay great heed to ISO specifications. Most producers of VDUs are international corporations. It is obvious that the best and most effective solutions to workplace design problems from the international manufacturers’ point of view should be agreed upon internationally. Many regional authorities, such as the European Standardization Organization (CEN) have adopted ISO standards wherever appropriate. The Vienna Agreement, signed by the ISO and CEN, is the official instrument which ensures effective collaboration between the two organizations. As different parts of ISO 9241 are approved and published as international standards, they are adopted as European standards and become part of EN 29241. Since CEN standards replace national standards in the European Union (EU) and the European Free Trade Agreement (EFTA) Member States, the significance of ISO standards in Europe has grown, and, in turn, has also increased pressure on the ISO to efficiently produce standards and guidelines for VDUs.

User performance standards

An alternative to product standards is to develop user performance standards. Thus, rather than specify a product feature such as character height which it is believed will result in a legible display, standards makers develop procedures for testing directly such characteristics as legibility. The standard is then stated in terms of the user performance required from the equipment and not in terms of how that is achieved. The performance measure is a composite including speed and accuracy and the avoidance of discomfort.

User performance standards have a number of advantages; they are

- relevant to the real problems experienced by users

- tolerant of developments in the technology

- flexible enough to cope with interactions between factors.

However, user performance standards can also suffer a number of disadvantages. They cannot be totally complete and scientifically valid in all cases, but do represent reasonable compromises, which require significant time to obtain the agreement of all the parties involved in standards-setting.

Coverage and Use of ISO 9241

The VDU ergonomics requirements standard, ISO 9241, provides detail on ergonomic aspects of products, and on assessing the ergonomic properties of a system. All references to ISO 9241 also apply to EN 29241. Some parts provide general guidance to be considered in the design of equipment, software and tasks. Other parts include more specific design guidance and requirements relevant to current technology, since such guidance is useful to designers. In addition to product specifications, ISO 9241 emphasizes the need to specify factors affecting user performance, including how to assess user performance in order to judge whether or not a system is appropriate to the context in which it will be used.

ISO 9241 has been developed with office-based tasks and environments in mind. This means that in other specialized environments some acceptable deviation from the standard may be needed. In many cases, this adaptation of the office standard will achieve a more satisfactory result than the “blind” specification or testing of an isolated standard specific to a given situation. Indeed, one of the problems with VDU ergonomics standards is that the technology is developing faster than standards makers can work. Thus it is quite possible that a new device may fail to meet the strict requirements in an existing standard because it approaches the need in question in a way radically different from any that were foreseen when the original standard was written. For example, early standards for character quality on a display assumed a simple dot matrix construction. Newer more legible fonts would have failed to meet the original requirement because they would not have the specified number of dots separating them, a notion inconsistent with their design.

Unless standards are specified in terms of the performance to be achieved, the users of ergonomics standards must allow suppliers to meet the requirement by demonstrating that their solution provides equivalent or superior performance to achieve the same objective.

The use of the ISO 9241 standard in the specification and procurement process places display screen ergonomics issues firmly on management’s agenda and helps to ensure proper consideration of these issues by both procurer and supplier. The standard is therefore a useful part of the responsible employer’s strategy for protecting the health, safety and productivity of display screen users.

General issues

ISO 9241 Part 1 General introduction explains the principles underlying the multipart standard. It describes the user performance approach and provides guidance on how to use the standard and on how conformance to parts of ISO 9241 should be reported.

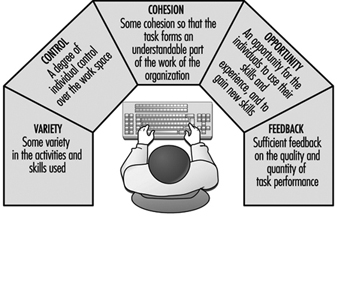

ISO 9241 Part 2 Guidance on task requirements provides guidance on job and task design for those responsible for planning VDU work in order to enhance the efficiency and the well-being of individual users by applying practical ergonomic knowledge to the design of office VDU tasks. Objectives and characteristics of task design are also discussed (see figure 2) and the standard describes how task requirements may be identified and specified within individual organizations and can be incorporated into the organization’s system design and implementation process.

Figure 2. Guidance and task requirements

Case Study: Display Screen Equipment Directive (90/270/EEC)

The Display Screen Directive is one in a series of “daughter”directives dealing with specific aspects of health and safety. The directives form part of the European Union’s programme for promoting health and safety in the single market. The “parent” or “Framework” Directive (89/391/EEC) sets out the general principles of the Community’s approach to Health and Safety. These common principles include the avoidance of risk, where possible, by eliminating the source of the risk and the encouragement of collective protective measures instead of individual protective measures.

Where risk is unavoidable, it must be properly evaluated by people with the relevant skills and measures must be taken which are appropriate to the extent of the risk. Thus if the assessment shows that the level of risk is slight, informal measures may be entirely adequate. However, where significant risk is identified, then stringent measures must be taken. The Directive itself only placed obligations on Member States of the EU, not on individual employers or manufacturers. The Directive required Member States to transpose the obligations into appropriate national laws, regulations and administrative provisions. These in turn place obligations on employers to ensure a minimum level of health and safety for display screen users. The main obligations are for employers to: The intention behind the Display Screen Directive is to specify how workstations should be used rather than how products should be designed. The obligations therefore fall on employers, not on manufacturers of workstations. However, many employers will ask their suppliers to reassure them that their products “conform”. In practice, this means little since there are only a few, relatively simple design requirements in the Directive. These are contained in the Annex (not given here) and concern the size and reflectance of the work surface,the adjustability of the chair, the separation of the keyboard and the clarity of the displayed image.

Hardware and environmental ergonomics issues

Display screen

ISO 9241 (EN 29241) Part 3 Visual display requirements specifies the ergonomic requirements for display screens which ensure that they can be read comfortably, safely and efficiently to perform office tasks. Although it deals specifically with displays used in offices, the guidance is appropriate to specify for most applications which require general purpose displays. A user performance test which, once approved, can serve as the basis for performance testing and will become an alternate route to compliance for VDUs.

ISO 9241 Part 7 Display requirements with reflections. The purpose of this part is to specify methods of measurement of glare and reflections from the surface of display screens, including those with surface treatments. It is aimed at display manufacturers who wish to ensure that anti-reflection treatments do not detract from image quality.

ISO 9241 Part 8 Requirements for displayed colours. The purpose of this part is to deal with the requirements for multicolour displays which are largely in addition to the monochrome requirements in Part 3, requirements for visual display in general.

Keyboard and other input devices

ISO 9241 Part 4 Keyboard requirements requires that the keyboard should be tiltable, separate from the display and easy to use without causing fatigue in the arms or hands. This standard also specifies the ergonomic design characteristics of an alphanumeric keyboard which may be used comfortably, safely and efficiently to perform office tasks. Again, although Part 4 is a standard to be used for office tasks, it is appropriate to most applications which require general purpose alphanumeric keyboards. Design specifications and an alternative performance test method of compliance are included.

ISO 9241 Part 9 Requirements for non-keyboard input devices specifies the ergonomic requirements from such devices as the mouse and other pointing devices which may be used in conjunction with a visual display unit. It also includes a performance test.

Workstations

ISO 9241 Part 5 Workstation layout and postural requirements facilitates efficient operation of the VDU and encourages the user to adopt a comfortable and healthy working posture. The requirements for a healthy, comfortable posture are discussed. These include:

- the location of frequently used equipment controls, displays and work surfaces within easy reach

- the opportunity to change position frequently

- the avoidance of excessive, frequent and repetitive movements with extreme extension or rotation of the limbs or trunk

- support for the back allowing an angle of 90 degrees to 110 degrees between back and thighs.

The characteristics of the workplace which promote a healthy and comfortable posture are identified and design guidelines given.

Working environments

ISO 9241 Part 6 Environmental requirements specifies the ergonomic requirements for the visual display unit working environment which will provide the user with comfortable, safe and productive working conditions. It covers the visual, acoustic and thermal environments. The objective is to provide a working environment which should facilitate efficient operation of the VDU and provide the user with comfortable working conditions.

The characteristics of the working environment which influence efficient operation and user comfort are identified, and design guidelines presented. Even when it is possible to control the working environment within strict limits, individuals will differ in their judgements of its acceptability, partly because individuals vary in their preferences and partly because different tasks may require quite different environments. For example, users who sit at VDUs for prolonged periods are far more sensitive to draughts than users whose work involves moving about an office and only working at the VDU intermittently.

VDU work often restricts the opportunities that individuals have for moving about in an office and so some individual control over the environment is highly desirable. Care must be taken in common work areas to protect the majority of users from extreme environments which may be preferred by some individuals.

Software ergonomics and dialogue design

ISO 9241 Part 10 Dialogue principles presents ergonomic principles which apply to the design of dialogues between humans and information systems, as follows:

- suitability for the task

- self-descriptiveness

- controllability

- conformity with user expectations

- error tolerance

- suitability for individualization

- suitability for learning.

The principles are supported by a number of scenarios which indicate the relative priorities and importance of the different principles in practical applications. The starting point for this work was the German DIN 66234 Part 8 Principles of Ergonomic Dialogue Design for Workplaces with Visual Display Units.

ISO 9241 Part 11 Guidance on usability specification and measures helps those involved in specifying or measuring usability by providing a consistent and agreed framework of the key issues and parameters involved. This framework can be used as part of an ergonomic requirements specification and it includes descriptions of the context of use, the evaluation procedures to be carried out and the criterion measures to be satisfied when the usability of the system is to be evaluated.

ISO 9241 Part 12 Presentation of information provides guidance on the specific ergonomics issues involved in representing and presenting information in a visual form. It includes guidance on ways of representing complex information, screen layout and design and the use of windows. It is a useful summary of the relevant materials available among the substantial body of guidelines and recommendations which already exist. The information is presented as guidelines without any need for formal conformance testing.

ISO 9241 Part 13 User guidance provides manufacturers with, in effect, guidelines on how to provide guidelines to users. These include documentation, help screens, error handling systems and other aids that are found in many software systems. In assessing the usability of a product in practice, real users should take into account the documentation and guidance provided by the supplier in the form of manuals, training and so on, as well as the specific characteristics of the product itself.

ISO 9241 Part 14 Menu dialogues provides guidance on the design of menu-based systems. It applies to text-based menus as well as to pull-down or pop-up menus in graphical systems. The standard contains a large number of guidelines developed from the published literature and from other relevant research. In order to deal with the extreme variety and complexity of menu-based systems, the standard employs a form of “conditional compliance”. For each guideline, there are criteria to help establish whether or not it is applicable to the system in question. If it is determined that the guidelines are applicable, criteria to establish whether or not the system meets those requirements are provided.

ISO 9241 Part 15 Command dialogues provides guidance for the design of text-based command dialogues. Dialogues are the familiar boxes which come onto the screen and query the VDU user, such as in a search command. The software creates a “dialogue” in which the user must supply the term to be found, and any other relevant specifications about the term, such as its case or format.

ISO 9241 Part 16 Direct manipulation dialogues deals with the design of direct manipulation dialogues and WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) dialogue techniques, whether provided as the sole means of dialogue or combined with some other dialogue technique. It is envisaged that the conditional compliance developed for Part 14 may be appropriate for this mode of interaction also.

ISO 9241 Part 17 Form-filling dialogues is in the very early stages of development.