During the 1990s, the organizational factors in safety policy are becoming increasingly important. At the same time, the views of organizations regarding safety have dramatically changed. Safety experts, most of whom have a technical training background, are thus confronted with a dual task. On the one hand, they have to learn to understand the organizational aspects and take them into account in constructing safety programmes. On the other hand, it is important that they be aware of the fact that the view of organizations is moving further and further away from the machine concept and placing a clear emphasis on less tangible and measurable factors such as organizational culture, behaviour modification, responsibility-raising or commitment. The first part of this article briefly covers developments in opinions relating to organizations, management, quality and safety. The second part of the article defines the implications of these developments for audit systems. This is then very briefly placed in a tangible context using the example of an actual safety audit system based on the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001 standards.

New Opinions Concerning Organization and Safety

Changes in social-economic circumstances

The economic crisis that started to impact upon the Western world in 1973 has had a significant influence on thought and action in the field of management, quality and work safety. In the past, the accent in economic development was placed on expansion of the market, increasing exports and improving productivity. However, the emphasis gradually shifted to the reduction of losses and the improvement of quality. In order to retain and acquire customers, a more direct response was provided to their requirements and expectations. This resulted in a need for greater product differentiation, with the direct consequence of greater flexibility within organizations in order to always be able to respond to market fluctuations on a “just in time” basis. Emphasis was placed on the commitment and creativity of employees as the major competitive advantage in the economic competitive struggle. Besides increasing quality, limiting loss-making activities became an important means of improving operating results.

Safety experts enlisted in this strategy by developing and instituting “total loss control” programmes. Not only are the direct costs of accidents or the increased insurance premiums significant in these programmes, but so also are all direct or indirect unnecessary costs and losses. A study of how much production should be increased in real terms to compensate for these losses immediately reveals that reducing costs is today often more efficient and profitable than increasing production.

In this context of improved productivity, reference was recently made to the major benefits of reducing absenteeism due to sickness and stimulating employee motivation. Against the background of these developments, safety policy is increasingly and clearly taking on a new form with different accents. In the past, most corporate leaders considered work safety as merely a legal obligation, as a burden they would quickly delegate to technical specialists. Today, safety policy is more and more distinctly being viewed as a way of achieving the two aims of reducing losses and optimizing corporate policy. Safety policy is therefore increasingly evolving into a reliable barometer of the soundness of the corporation’s success with respect to these aims. In order to measure progress, increased attention is being devoted to management and safety audits.

Organizational Theory

It is not only economic circumstances that have given company heads new insights. New visions relating to management, organizational theory, total quality care and, in the same vein, safety care, are resulting in significant changes. An important turning point in views on the organization was elaborated in the renowned work published by Peters and Waterman (1982), In Search of Excellence. This work was already espousing the ideas which Pascale and Athos (1980) discovered in Japan and described in The Art of Japanese Management. This new development can be symbolized in a sense by McKinsey’s “7-S” Framework (in Peters and Waterman 1982). In addition to three traditional management aspects (Strategy, Structure and Systems), corporations now also emphasize three additional aspects ( Staff, Skills and Style). All six of these interact to provide the input to the 7th “S”, Superordinate goals (figure 1). With this approach, a very clear accent is placed on the human-oriented aspects of the organization.

Figuer 1.The values, mission and organizational culture of a corporation according to McKinsey’s 7-S Framework

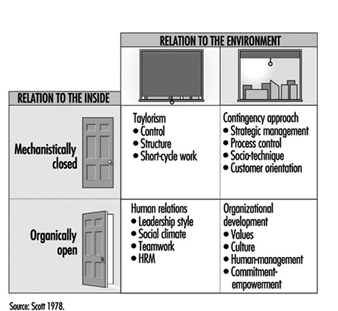

The fundamental shifts can best be demonstrated on the basis of the model presented by Scott (1978), which was also used by Peters and Waterman (1982). This model uses two approaches:

- The closed-system approaches deny the influence of developments from outside the organization. With the mechanistic closed approaches, the objectives of an organization are clearly defined and can be logically and rationally determined.

- Open-system approaches take outside influences fully into account, and the objectives are more the result of diverse processes, in which clearly irrational factors contribute to decision making. These organically open approaches more truly reflect the evolution of an organization, which is not determined mathematically or on the basis of deductive logic, but grows organically on the basis of real people and their interactions and values (figure 2).

Figure 2.Organizational Theories

Four fields are thus created in figure 2 . Two of these (Taylorism and contingency approach) are mechanically closed, and the other two (human relations and organizational development) are organically open. There has been enormous development in management theory, moving from the traditional rational and authoritarian machine model (Taylorism) to the human-oriented organic model of human resources management (HRM).

Organizational effectiveness and efficiency are being more clearly linked to optimal strategic management, a flat organizational structure and sound quality systems. Furthermore, attention is now given to superordinate goals and significant values that have a bonding effect within the organization, such as skills (on the basis of which the organization stands out from its competitors) and a staff that is motivated to maximum creativity and flexibility by placing the emphasis on commitment and empowerment. With these open approaches, a management audit cannot limit itself to a number of formal or structural characteristics of the organization. The audit must also include a search for methods to map out less tangible and measurable cultural aspects.

From product control to total quality management

In the 1950s, quality was limited to a post-factum end product control, total quality control (TQC). In the 1970s, partly stimulated by NATO and the automotive giant Ford, the accent shifted to the achievement of the goal of total quality assurance (TQA) during the production process. It was only during the 1980s that, stimulated by Japanese techniques, attention shifted towards the quality of the total management system and total quality management (TQM) was born. This fundamental change in the quality care system has taken place cumulatively in the sense that each foregoing stage was integrated into the next. It is also clear that while product control and safety inspection are facets more closely related to a Tayloristic organizational concept, quality assurance is more associated with a socio-technical system approach where the aim is not to betray the trust of the (external) customer. TQM, finally, relates to an HRM approach by the organization as it is no longer solely the improvement of the product that is involved, but continuous improvement of the organizational aspects in which explicit attention is also devoted to the employees.

In the total quality leadership (TQL) approach of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), the emphasis is very strongly placed on the equal impact of the organization on the customer, the employees and the overall society, with the environment as the key point of attention. These objectives can be realized by including concepts such as “leadership” and “people management”.

It is clear that there is also a very important difference in emphasis between quality assurance as described in the ISO standards and the TQL approach of the EFQM. ISO quality assurance is an extended and improved form of quality inspection, focusing not only on the products and internal customers, but also on the efficiency of the technical processes. The objective of the inspection is to investigate the conformity with the procedures set out in ISO. TQM, on the other hand, endeavours to meet the expectations of all internal and external customers as well as all processes within the organization, including the more soft and human-oriented ones. The involvement, the commitment and the creativity of the employees are clearly important aspects of TQM.

From Human Error to Integrated Safety

Safety policy has evolved in a similar manner to quality care. Attention has shifted from post-factum accident analysis, with emphasis on the prevention of injuries, to a more global approach. Safety is seen more in the context of “total loss control” - a policy aimed at the avoidance of losses through management of safety involving the interaction of people, processes, materials, equipment, installations and the environment. Safety therefore focuses on the management of the processes that could lead to losses. In the initial development period of safety policy the emphasis was placed on a human error approach. Consequently, employees were given a heavy responsibility for the prevention of industrial accidents. Following a Tayloristic philosophy, conditions and procedures were drawn up and a control system was established to maintain the prescribed standards of behaviour. This philosophy may filter through into modern safety policy via the ISO 9000 concepts resulting in the imposition of a sort of implicit and indirect feeling of guilt upon the employees, with all the adverse consequences this entails for the corporate culture - for instance, a tendency may develop that performance will be impeded rather than enhanced.

At a later stage in the evolution of safety policy, it was recognized that employees carry out their work in a particular environment with well-defined working resources. Industrial accidents were considered as a multicausal event in a human/machine/environment system in which the emphasis shifted in a technical-system approach. Here again we find the analogy with quality assurance, where the accent is placed on controlling technical processes through means such as statistical process control.

Only recently, and partly stimulated by the TQM philosophy, has the emphasis in safety policy systems shifted into a social-system approach, which is a logical step in the improvement of the prevention system. In order to optimize the human/machine/environment system it is not sufficient to ensure safe machines and tools by means of a well-developed prevention policy, but there is also the need for a preventive maintenance system and the assurance of security among all technical processes. Moreover, it is of crucial importance that employees be sufficiently trained, skilled and motivated with regard to health and safety objectives. In today’s society, the latter objective can no longer be achieved through the authoritarian Tayloristic approach, as positive feedback is much more stimulating than a repressive control system that often has only negative effects. Modern management entails an open, motivating corporate culture, in which there is a common commitment to achieving key corporate objectives in a participatory, team-based approach. In the safety-culture approach, safety is an integral part of the objectives of the organizations and therefore an essential part of everyone’s task, starting with top management and passing along the entire hierarchical line down to employees on the shop floor.

Integrated safety

The concept of integrated safety immediately presents a number of central factors in an integrated safety system, the most important of which can be summarized as follows:

A clearly visible commitment from the top management. This commitment is not only given on paper, but is translated right down to the shop floor in practical achievements.

Active involvement of the hierarchical line and the central support departments. Care for safety, health and welfare is not only an integral part of everyone’s task in the production process, but is also integrated into the personnel policy, into preventive maintenance, into the design stage and into working with third parties.

Full participation of the employees. Employees are full discussion partners with whom open and constructive communication is possible, with their contribution being given full weight. Indeed, participation is of crucial importance for carrying through corporate and safety policy in an efficient and motivating way.

A suitable profile for a safety expert. The safety expert is no longer the technician or jack of all trades, but is a qualified adviser to the top management, with particular attention being devoted to optimizing the policy processes and the safety system. He or she is therefore not someone who is only technically trained, but also a person who, as a good organizer, can deal with people in an inspiring manner and collaborate in a synergetic way with other prevention experts.

A pro-active safety culture. The key aspect of an integrated safety policy is a pro-active safety culture, which includes, among other things, the following:

- Safety, health and welfare are the key ingredients of an organization’s value system and of the objectives it seeks to attain.

- An atmosphere of openness prevails, based on mutual trust and respect.

- There is a high level of cooperation with a smooth flow of information and an appropriate level of coordination.

- A pro-active policy is implemented with a dynamic system of constant improvement perfectly matching the prevention concept.

- The promotion of safety, health and welfare is a key component of all decision-making, consultations and teamwork.

- When industrial accidents occur, suitable preventive measures are sought, not a scapegoat.

- Members of staff are encouraged to act on their own initiative so that they possess the greatest possible authority, knowledge and experience, enabling them to intervene in an appropriate manner in unexpected situations.

- Processes are set in motion with a view to promoting individual and collective training to the maximum extent possible.

- Discussions concerning challenging and attainable health, safety and welfare objectives are held on a regular basis.

Safety and Management Audits

General description

Safety audits are a form of risk analysis and evaluation in which a systematic investigation is carried out in order to determine the extent to which the conditions are present that provide for the development and implementation of an effective and efficient safety policy. Each audit therefore simultaneously envisions the objectives that must be realized and the best organizational circumstances to put these into practice.

Each audit system should, in principle, determine the following:

- What is management seeking to achieve, by what means and by what strategy?

- What are the necessary provisions in terms of resources, structures, processes, standards and procedures that are required to achieve the proposed objectives, and what has been provided? What minimum programme can be put forward?

- What are the operational and measurable criteria that must be met by the chosen items to allow the system to function optimally?

The information is then thoroughly analysed to examine to what extent the current situation and the degree of achievement meet the desired criteria, followed by a report with positive feedback that emphasizes the strong points, and corrective feedback that refers to aspects requiring further improvement.

Auditing and strategies for change

Each audit system explicitly or implicitly contains a vision both of an ideal organization’s design and conceptualization, and of the best way of implementing improvements.

Bennis, Benne and Chin (1985) distinguish three strategies for planned changes, each based on a different vision of people and of the means of influencing behaviour:

- Power-force strategies are based on the idea that the behaviour of employees can be changed by exercising sanctions.

- Rational-empirical strategies are based on the axiom that people make rational choices depending on maximizing their own benefits.

- Normative-re-educative strategies are based on the premise that people are irrational, emotional beings and in order to realize a real change, attention must also be devoted to their perception of values, culture, attitudes and social skills.

Which influencing strategy is most appropriate in a specific situation not only depends on the starting vision, but also on the actual situation and the existing organizational culture. In this respect it is very important to know which sort of behaviour to influence. The famous model devised by Danish risk specialist Rasmussen (1988) distinguishes among the following three sorts of behaviour:

- Routine actions (skill-based behaviour) automatically follow the associated signal. Such actions are carried out without one’s consciously devoting attention to them - for example, touch-typing or manually changing gears when driving.

- Actions in accordance with instructions (rule-based) require more conscious attention because no automatic response to the signal is present and a choice must be made between different possible instructions and rules. These are often actions which can be placed in an “ifthen” sequence, as in “If the meter rises to 50 then this valve must be closed”.

- Actions based on knowledge and insight (knowledge-based) are carried out after a conscious interpretation and evaluation of the different problem signals and the possible alternative solutions. These actions therefore presuppose a fairly high degree of knowledge of and insight into the process concerned, and the ability to interpret unusual signals.

Strata in behavioural and cultural change

Based on the above, most audit systems (including those based on the ISO series of standards) implicitly depart from power-force strategies or rational-empirical strategies, with their emphasis on routine or procedural behaviour. This means that insufficient attention is paid in these audit systems to “knowledge-based behaviour” that can be influenced mainly via normative–re-educative strategies. In the typology used by Schein (1989), attention is devoted only to the tangible and conscious surface phenomena of the organizational culture and not to the deeper invisible and subconscious strata that refer more to values and fundamental presuppositions.

Many audit systems limit themselves to the question of whether a particular provision or procedure is present. It is therefore implicitly assumed that the sheer existence of this provision or procedure is a sufficient guarantee for the good functioning of the system. Besides the existence of certain measures, there are always different other “strata” (or levels of probable response) that must be addressed in an audit system to provide sufficient information and guarantees for the optimum functioning of the system.

In more concrete terms, the following example concerns response to a fire emergency:

- A given provision, instruction or procedure is present (“sound the alarm and use the extinguisher”).

- A given instruction or procedure is also familiarly known to the parties concerned (workers know where alarms and extinguishers are located and how to activate and use them).

- The parties concerned also know as much as possible as to the “why and wherefore” of a particular measure (employees have been trained or educated in extinguisher use and typical types of fires).

- The employee is also motivated to apply needful measures (self preservation, save the job, etc.).

- There is sufficient motivation, competence and ability to act in unforeseen circumstances (employees know what to do in the event fire gets out of hand, requiring professional fire-fighting response).

- There are good human relations and an atmosphere of open communication (supervisors, managers and employees have discussed and agreed upon fire emergency response procedures).

- Spontaneous creative processes originate in a learning organiz-ation (changes in procedures are implemented following “lessons learned” in actual fire situations).

Table 1 lays out some strata in quality audio safety policy.

Table 1. Strata in quality and safety policy

|

Strategies |

Behaviour |

||

|

Skills |

Rules |

Knowledge |

|

|

Power-force |

Human error approach |

||

|

Rational-empirical |

Technical system approach |

||

|

Normative-re-educative |

Social system approach TQM |

Safety culture approach PAS EFQM |

|

The Pellenberg Audit System

The name Pellenberg Audit System (PAS) derives from the place where the designers gathered many times to develop the system (the Maurissens Château in Pellenberg, a building of the Catholic University of Leuven). PAS is the result of intense collaboration by an interdisciplinary team of experts with years of practical experience, both in the area of quality management and in the area of safety and environmental problems, in which a variety of approaches and experiences were brought together. The team also received support from the university science and research departments, and thus benefited from the most recent insights in the fields of management and organizational culture.

PAS encompasses an entire set of criteria that a superior company prevention system ought to meet (see table 2). These criteria are classified in accordance with the ISO standard system (quality assurance in design, development, production, installation and servicing). However, PAS is not a simple translation of the ISO system into safety, health and welfare. A new philosophy is developed, departing from the specific product that is achieved in safety policy: meaningful and safe jobs. The contract of the ISO system is replaced by the provisions of the law and by the evolving expectations that exist among the parties involved in the social field with regard to health, safety and welfare. The creation of safe and meaningful jobs is seen as an essential objective of each organization within the framework of its social responsibility. The enterprise is the supplier and the customers are the employees.

Table 2. PAS safety audit elements

|

PAS safety audit elements |

Correspondence with ISO 9001 |

|

|

1. |

Management responsibility |

|

|

1.1. |

Safety policy |

4.1.1. |

|

1.2. |

Organization |

|

|

1.2.1. |

Responsibility and authority |

4.1.2.1. |

|

1.2.2. |

Verification resources and personnel |

4.1.2.2. |

|

1.2.3. |

Health and safety service |

4.1.2.3. |

|

1.3. |

Safety management system review |

4.1.3. |

|

2. |

Safety management system |

4.2. |

|

3. |

Obligations |

4.3. |

|

4. |

Design control |

|

|

4.1. |

General |

4.4.1. |

|

4.2. |

Design and development planning |

4.4.2. |

|

4.3. |

Design input |

4.4.3. |

|

4.4. |

Design output |

4.4.4. |

|

4.5. |

Design verification |

4.4.5. |

|

4.6. |

Design changes |

4.4.6. |

|

5. |

Document control |

|

|

5.1. |

Document approval and issue |

4.5.1. |

|

5.2. |

Document changes/modifications |

4.5.2. |

|

6. |

Purchasing and contracting |

|

|

6.1. |

General |

4.6.1. |

|

6.2. |

Assessment of suppliers and contractors |

4.6.2. |

|

6.3. |

Purchasing data |

4.6.3. |

|

6.4. |

Third party’s products |

4.7. |

|

7. |

Identification |

4.8. |

|

8. |

Process control |

|

|

8.1. |

General |

4.9.1. |

|

8.2. |

Process safety control |

4.11. |

|

9. |

Inspection |

|

|

9.1. |

Receiving and pre-start-up inspection |

4.10.1. |

|

9.2. |

Periodic inspections |

4.10.2. |

|

9.3. |

Inspection records |

4.10.4. |

|

9.4. |

Inspection equipment |

4.11. |

|

9.5. |

Inspection status |

4.12. |

|

10. |

Accidents and incidents |

4.13. |

|

11. |

Corrective and preventive action |

4.13. |

|

12. |

Safety records |

4.16. |

|

13. |

Internal safety audits |

4.17. |

|

14. |

Training |

4.18. |

|

15. |

Maintenance |

4.19. |

|

16. |

Statistical techniques |

4.20. |

Several other systems are integrated in the PAS system:

- At a strategic level, the insights and requirements of ISO are of particular importance. As far as possible, these are comple-mented by the management vision as this was originally devel-oped by the European Foundation for Quality Management.

- At a tactical level, the systematics of the “Management’s Oversight and Risk Tree” encourages people to seek out what are the necessary and sufficient conditions in order to achieve the desired safety result.

- At an operational level a multitude of sources could be drawn upon, including existing legislation, regulations and other criteria such as the International Safety Rating System (ISRS), in which the emphasis is placed on certain concrete conditions that should guarantee the safety result.

The PAS constantly refers to the broader corporate policy within which the safety policy is embedded. After all, an optimum safety policy is at the same time a product and a producer of a pro-active company policy. Assuming that a safe company is at the same time an effective and efficient organization and vice versa, special attention is therefore devoted to the integration of safety policy in the overall policy. Essential ingredients of a future-oriented corporate policy include a strong corporate culture, a far-reaching commitment, the participation of the employees, a special emphasis on the quality of the work, and a dynamic system of continual improvement. Although these insights also partly form the background of the PAS, they are not always very easy to reconcile with the more formal and procedural approach of the ISO philosophy.

Formal procedures and directly identifiable results are indisputably important in safety policy. However, it is not enough to base the safety system on this approach alone. The future results of a safety policy are dependent on the present policy, on the systematic efforts, on the constant search for improvements, and particularly on the fundamental optimizing of processes that ensure durable results. This vision is incorporated in the PAS system, with strong emphasis among other things on a systematic improvement of the safety culture.

One of the main advantages of the PAS is the opportunity for synergy. By departing from the systematics of ISO, the diverse lines of approach become immediately recognizable for all those concerned with total quality management. There are clearly several opportunities for synergy between these various policy areas because in all these fields the improvement of the management processes is the key aspect. A careful purchasing policy, a sound system of preventive maintenance, good housekeeping, participatory management and the stimulation of an enterprising approach by employees are of paramount importance for all these policy areas.

The various care systems are organized in an analogous manner, based on principles such as the commitment of top management, the involvement of the hierarchical line, the active participation of employees, and a valorized contribution from the specific experts. The different systems also contain analogous policy instruments such as the policy statement, annual action plans, measuring and control systems, internal and external audits and so on. The PAS system therefore clearly invites the pursuance of an effective, cost-saving, synergetic cooperation between all these care systems.

The PAS does not offer the easiest road to achievement in the short term. Few company managers allow themselves to be seduced by a system that promises great benefits in the short term with little effort. Every sound policy requires an in-depth approach, with strong foundations being laid for future policy. More important than results in the short term is the guarantee that a system is being built up that will generate sustainable results in the future, not only in the field of safety, but also at the level of a generally effective and efficient corporate policy. In this respect working towards health, safety and welfare also means working towards safe and meaningful jobs, motivated employees, satisfied customers and an optimum operating result. All this takes place in a dynamic, pro-active atmosphere.

Summary

Continual improvement is an essential precondition for each safety audit system that seeks to reap lasting success in today’s rapidly evolving society. The best guarantee for a dynamic system of continual improvement and constant flexibility is the full commitment of competent employees who grow with the overall organization because their efforts are systematically valorized and because they are given the opportunities to develop and regularly update their skills. Within the safety audit process, the best guarantee of lasting results is the development of a learning organization in which both the employees and the organization continue to learn and evolve.