Safety culture is a new concept among safety professionals and academic researchers. Safety culture may be considered to include various other concepts referring to cultural aspects of occupational safety, such as safety attitudes and behaviours as well as a workplace’s safety climate, which are more commonly referred to and are fairly well documented.

A question arises whether safety culture is just a new word used to replace old notions, or does it bring new substantive content that may enlarge our understanding of the safety dynamics in organizations? The first section of this article answers this question by defining the concept of safety culture and exploring its potential dimensions.

Another question that may be raised about safety culture concerns its relationship to the safety performance of firms. It is accepted that similar firms classified in a given risk category frequently differ as to their actual safety performance. Is safety culture a factor of safety effectiveness, and, if so, what kind of safety culture will succeed in contributing to a desirable impact? This question is addressed in the second section of the article by reviewing some relevant empirical evidence concerning the impact of safety culture on safety performance.

The third section addresses the practical question of the management of the safety culture, in order to help managers and other organizational leaders to build a safety culture that contributes to the reduction of occupational accidents.

Safety Culture: Concept and Realities

The concept of safety culture is not yet very well defined, and refers to a wide range of phenomena. Some of these have already been partially documented, such as the attitudes and the behaviours of managers or workers towards risk and safety (Andriessen 1978; Cru and Dejours 1983; Dejours 1992; Dodier 1985; Eakin 1992; Eyssen, Eakin-Hoffman and Spengler 1980; Haas 1977). These studies are important for presenting evidence about the social and organizational nature of individuals’ safety attitudes and behaviours (Simard 1988). However, by focusing on particular organizational actors like managers or workers, they do not address the larger question of the safety culture concept, which characterizes organizations.

A trend of research which is closer to the comprehensive approach emphasized by the safety culture concept is represented by studies on the safety climate that developed in the 1980s. The safety climate concept refers to the perceptions workers have of their work environment, particularly the level of management’s safety concern and activities and their own involvement in the control of risks at work (Brown and Holmes 1986; Dedobbeleer and Béland 1991; Zohar 1980). Theoretically, it is believed that workers develop and use such sets of perceptions to ascertain what they believe is expected of them within the organizational environment, and behave accordingly. Though conceptualized as an individual attribute from a psychological perspective, the perceptions which form the safety climate give a valuable assessment of the common reaction of workers to an organizational attribute that is socially and culturally constructed, in this case by the management of occupational safety in the workplace. Consequently, although the safety climate does not completely capture the safety culture, it may be viewed as a source of information about the safety culture of a workplace.

Safety culture is a concept that (1) includes the values, beliefs and principles that serve as a foundation for the safety management system and (2) also includes the set of practices and behaviours that exemplify and reinforce those basic principles. These beliefs and practices are meanings produced by organizational members in their search for strategies addressing issues such as occupational hazards, accidents and safety at work. These meanings (beliefs and practices) are not only shared to a certain extent by members of the workplace but also act as a primary source of motivated and coordinated activity regarding the question of safety at work. It can be deduced that culture should be differentiated from both concrete occupational safety structures (the presence of a safety department, of a joint safety and health committee and so on) and existent occupational safety programmes (made up of hazards identification and control activities such as workplace inspections, accident investigation, job safety analysis and so on).

Petersen (1993) argues that safety culture “is at the heart of how safety systems elements or tools... are used” by giving the following example:

Two companies had a similar policy of investigating accidents and incidents as part of their safety programmes. Similar incidents occurred in both companies and investigations were launched. In the first company, the supervisor found that the workers involved behaved unsafely, immediately warned them of the safety infraction and updated their personal safety records. The senior manager in charge acknowledged this supervisor for enforcing workplace safety. In the second company, the supervisor considered the circumstances of the incident, namely that it occurred while the operator was under severe pressure to meet production deadlines after a period of mechanical maintenance problems that had slowed production, and in a context where the attention of employees was drawn from safety practices because recent company cutbacks had workers concerned about their job security. Company officials acknowledged the preventive maintenance problem and held a meeting with all employees where they discussed the current financial situation and asked workers to maintain safety while working together to improve production in view of helping the corporation’s viability.

“Why”, asked Petersen, “did one company blame the employee, fill out the incident investigation forms and get back to work while the other company found that it must deal with fault at all levels of the organization?” The difference lies in the safety cultures, not the safety programmes themselves, although the cultural way this programme is put into practice, and the values and beliefs that give meaning to actual practices, largely determine whether the programme has sufficient real content and impact.

From this example, it appears that senior management is a key actor whose principles and actions in occupational safety largely contribute to establish the corporate safety culture. In both cases, supervisors responded according to what they perceived to be “the right way of doing things”, a perception that had been reinforced by the consequent actions of top management. Obviously, in the first case, top management favoured a “by-the-book”, or a bureaucratic and hierarchical safety control approach, while in the second case, the approach was more comprehensive and conducive to managers’ commitment to, and workers’ involvement in, safety at work. Other cultural approaches are also possible. For example, Eakin (1992) has shown that in very small businesses, it is common that the top manager completely delegates responsibility for safety to the workers.

These examples raise the important question of the dynamics of a safety culture and the processes involved in the building, the maintenance and the change of organizational culture regarding safety at work. One of these processes is the leadership demonstrated by top managers and other organizational leaders, like union officers. The organizational culture approach has contributed to renewed studies of leadership in organizations by showing the importance of the personal role of both natural and organizational leaders in demonstrating commitment to values and creating shared meanings among organizational members (Nadler and Tushman 1990; Schein 1985). Petersen’s example of the first company illustrates a situation where top management’s leadership was strictly structural, a matter merely of establishing and reinforcing compliance to the safety programme and to rules. In the second company, top managers demonstrated a broader approach to leadership, combining a structural role in deciding to allow time to perform necessary preventive maintenance with a personal role in meeting with employees to discuss safety and production in a difficult financial situation. Finally, in Eakin’s study, senior managers of some small businesses seem to play no leadership role at all.

Other organizational actors who play a very important role in the cultural dynamics of occupational safety are middle managers and supervisors. In their study of more than one thousand first-line supervisors, Simard and Marchand (1994) show that a strong majority of supervisors are involved in occupational safety, though the cultural patterns of their involvement may differ. In some workplaces, the dominant pattern is what they call “hierarchical involvement” and is more control-oriented; in other organizations the pattern is “participatory involvement”, because supervisors both encourage and allow their employees to participate in accident-prevention activities; and in a small minority of organizations, supervisors withdraw and leave safety up to the workers. It is easy to see the correspondence between these styles of supervisory safety management and what has been previously said about the patterns of upper-level managers’ leadership in occupational safety. Empirically, though, the Simard and Marchand study shows that the correlation is not a perfect one, a circumstance that lends support to Petersen’s hypothesis that a major problem of many executives is how to build a strong, people-oriented safety culture among the middle and supervisory management. Part of this problem may be due to the fact that most of the lower-level managers are still predominantly production-minded and prone to blame workers for workplace accidents and other safety mishaps (DeJoy 1987 and 1994; Taylor 1981).

This emphasis on management should not be viewed as disregarding the importance of workers in the safety culture dynamics of workplaces. Workers’ motivation and behaviours regarding safety at work are influenced by the perceptions they have of the priority given to occupational safety by their supervisors and top managers (Andriessen 1978). This top-down pattern of influence has been proven in numerous behavioural experiments, using managers’ positive feedback to reinforce compliance to formal safety rules (McAfee and Winn 1989; Näsänen and Saari 1987). Workers also spontaneously form work groups when the organization of work offers appropriate conditions that allow them to get involved in the formal or informal safety management and regulation of the workplace (Cru and Dejours 1983; Dejours 1992; Dwyer 1992). This latter pattern of workers’ behaviours, more oriented towards the safety initiatives of work groups and their capacity for self-regulation, may be used positively by management to develop workforce involvement and safety in the building of a workplace’s safety culture.

Safety Culture and Safety Performance

There is a growing body of empirical evidence concerning the impact of safety culture on safety performance. Numerous studies have investigated characteristics of companies having low accident rates, while generally comparing them with similar companies having higher-than-average accident rates. A fairly consistent result of these studies, conducted in industrialized as well as in developing countries, emphasizes the importance of senior managers’ safety commitment and leadership for safety performance (Chew 1988; Hunt and Habeck 1993; Shannon et al. 1992; Smith et al. 1978). Moreover, most studies show that in companies with lower accident rates, the personal involvement of top managers in occupational safety is at least as important as their decisions in the structuring of the safety management system (functions that would include the use of financial and professional resources and the creation of policies and programmes, etc.). According to Smith et al. (1978) active involvement of senior managers acts as a motivator for all levels of management by keeping up their interest through participation, and for employees by demonstrating management’s commitment to their well-being. Results of many studies suggest that one of the best ways of demonstrating and promoting its humanistic values and people-oriented philosophy is for senior management to participate in highly visible activities, such as workplace safety inspections and meetings with employees.

Numerous studies regarding the relationship between safety culture and safety performance pinpoint the safety behaviours of first-line supervisors by showing that supervisors’ involvement in a participative approach to safety management is generally associated with lower accident rates (Chew 1988; Mattila, Hyttinen and Rantanen 1994; Simard and Marchand 1994; Smith et al. 1978). Such a pattern of supervisors’ behaviour is exemplified by frequent formal and informal interactions and communications with workers about work and safety, paying attention to monitoring workers’ safety performance and giving positive feedback, as well as developing the involvement of workers in accident-prevention activities. Moreover, the characteristics of effective safety supervision are the same as those for generally efficient supervision of operations and production, thereby supporting the hypothesis that there is a close connection between efficient safety management and good general management.

There is evidence that a safety-oriented workforce is a positive factor for the firm’s safety performance. However, perception and conception of workers’ safety behaviours should not be reduced to just carefulness and compliance with management safety rules, though numerous behavioural experiments have shown that a higher level of workers’ conformity to safety practices reduces accident rates (Saari 1990). Indeed, workforce empowerment and active involvement are also documented as factors of successful occupational safety programmes. At the workplace level, some studies offer evidence that effectively functioning joint health and safety committees (consisting of members who are well trained in occupational safety, cooperate in the pursuit of their mandate and are supported by their constituencies) significantly contribute to the firm’s safety performance (Chew 1988; Rees 1988; Tuohy and Simard 1992). Similarly, at the shop-floor level, work groups that are encouraged by management to develop team safety and self-regulation generally have a better safety performance than work groups subject to authoritarianism and social disintegration (Dwyer 1992; Lanier 1992).

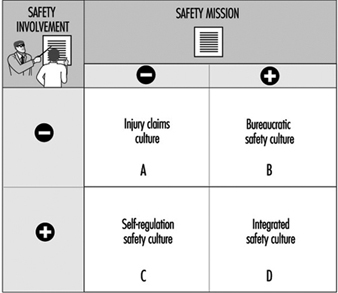

It can be concluded from the above-mentioned scientific evidence that a particular type of safety culture is more conducive to safety performance. In brief, this safety culture combines top management’s leadership and support, lower management’s commitment and employees’ involvement in occupational safety. Actually, such a safety culture is one that scores high on what could be conceptualized as the two major dimensions of the safety culture concept, namely safety mission and safety involvement, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Typology of safety cultures

Safety mission refers to the priority given to occupational safety in the firm’s mission. Literature on organizational culture stresses the importance of an explicit and shared definition of a mission that grows out of and supports the key values of the organization (Denison 1990). Consequently, the safety mission dimension reflects the degree to which occupational safety and health are acknowledged by top management as a key value of the firm, and the degree to which upper-level managers use their leadership to promote the internalization of this value in management systems and practices. It can then be hypothesized that a strong sense of safety mission (+) impacts positively on safety performance because it motivates individual members of the workplace to adopt goal-directed behaviour regarding safety at work, and facilitates coordination by defining a common goal as well as an external criterion for orienting behaviour.

Safety involvement is where supervisors and employees join together to develop team safety at the shop-floor level. Literature on organizational culture supports the argument that high levels of involvement and participation contribute to performance because they create among organizational members a sense of ownership and responsibility leading to a greater voluntary commitment that facilitates the coordination of behaviour and reduces the necessity of explicit bureaucratic control systems (Denison 1990). Moreover, some studies show that involvement can be a managers’ strategy for effective performance as well as a workers’ strategy for a better work environment (Lawler 1986; Walton 1986).

According to figure 1, workplaces combining a high level of these two dimensions should be characterized by what we call an integrated safety culture, which means that occupational safety is integrated into the organizational culture as a key value, and into the behaviours of all organizational members, thereby reinforcing involvement from top managers down to the rank-and-file employees. The empirical evidence mentioned above supports the hypothesis that this type of safety culture should lead workplaces to the best safety performance when compared to other types of safety cultures.

The Management of an Integrated Safety Culture

Managing an integrated safety culture first requires the senior management’s will to build it into the organizational culture of the firm. This is no simple task. It goes far beyond adopting an official corporate policy emphasizing the key value and priority given to occupational safety and to the philosophy of its management, although indeed the integration of safety at work in the organization’s core values is a cornerstone in the building of an integrated safety culture. Indeed, top management should be conscious that such a policy is the starting point of a major organizational change process, since most organizations are not yet functioning according to an integrated safety culture. Of course, the details of the change strategy will vary depending on what the workplace’s existing safety culture already is (see cells A, B and C of figure 1). In any case, one of the key issues is for the top management to behave congruently with such a policy (in other words to practice what it preaches). This is part of the personal leadership top managers should demonstrate in implementing and enforcing such a policy. Another key issue is for senior management to facilitate the structuring or restructuring of various formal management systems so as to support the building of an integrated safety culture. For example, if the existing safety culture is a bureaucratic one, the role of the safety staff and joint health and safety committee should be reoriented in such a way as to support the development of supervisors’ and work teams’ safety involvement. In the same way, the performance evaluation system should be adapted so as to acknowledge lower-level managers’ accountability and the performance of work groups in occupational safety.

Lower-level managers, and particularly supervisors, also play a critical role in the management of an integrated safety culture. More specifically, they should be accountable for the safety performance of their work teams and they should encourage workers to get actively involved in occupational safety. According to Petersen (1993), most lower-level managers tend to be cynical about safety because they are confronted with the reality of upper management’s mixed messages as well as the promotion of various programmes that come and go with little lasting impact. Therefore, building an integrated safety culture often may require a change in the supervisors’ pattern of safety behaviour.

According to a recent study by Simard and Marchand (1995), a systematic approach to supervisors’ behaviour change is the most efficient strategy to effect change. Such an approach consists of coherent, active steps aimed at solving three major problems of the change process: (1) the resistance of individuals to change, (2) the adaptation of existing management formal systems so as to support the change process and (3) the shaping of the informal political and cultural dynamics of the organization. The latter two problems may be addressed by upper managers’ personal and structural leadership, as mentioned in the preceding paragraph. However, in unionized workplaces, this leadership should shape the organization’s political dynamics so as to create a consensus with union leaders regarding the development of participative safety management at the shop-floor level. As for the problem of supervisors’ resistance to change, it should not be managed by a command-and-control approach, but by a consultative approach which helps supervisors participate in the change process and develop a sense of ownership. Techniques such as the focus group and ad hoc committee, which allow supervisors and work teams to express their concerns about safety management and to engage in a problem-solving process, are frequently used, combined with appropriate training of supervisors in participative and effective supervisory management.

It is not easy to conceive a truly integrated safety culture in a workplace that has no joint health and safety committee or worker safety delegate. However, many industrialized and some developing countries now have laws and regulations that encourage or mandate workplaces to establish such committees and delegates. The risk is that these committees and delegates may become mere substitutes for real employee involvement and empowerment in occupational safety at the shop-floor level, thereby serving to reinforce a bureaucratic safety culture. In order to support the development of an integrated safety culture, joint committees and delegates should foster a decentralized and participative safety management approach, for example by (1) organizing activities that raise employees’ consciousness of workplace hazards and risk-taking behaviours, (2) designing procedures and training programmes that empower supervisors and work teams to solve many safety problems at the shop-floor level, (3) participating in the workplace’s safety performance appraisal and (4) giving reinforcing feedback to supervisors and workers.

Another powerful means of promoting an integrated safety culture among employees is to conduct a perception survey. Workers generally know where many of the safety problems are, but since no one asks them their opinion, they resist getting involved in the safety programme. An anonymous perception survey is a means to break this stalemate and promote employees’ safety involvement while providing senior management with feedback that can be used to improve the safety programme’s management. Such a survey can be done using an interview method combined with a questionnaire administered to all or to a statistically valid sample of employees (Bailey 1993; Petersen 1993). The survey follow-up is crucial for building an integrated safety culture. Once the data are available, top management should proceed with the change process by creating ad hoc work groups with participation from every echelon of the organization, including workers. This will provide for more in-depth diagnoses of problems identified in the survey and will recommend ways of improving aspects of the safety management that need it. Such a perception survey may be repeated every year or two, in order to periodically assess the improvement of their safety management system and culture.