Animal husbandry—the rearing and use of animals—involves a wide variety of activities, including breeding, feeding, moving animals from one location to another, basic care (e.g., hoof care, cleaning, vaccinations), care for injured animals (either by animal handlers or veterinarians) and activities associated with particular animals (e.g., milking of cows, shearing of sheep, working with draught animals).

Such handling of livestock is associated with a variety of injuries and illnesses among humans. These injuries and illnesses may be due to direct exposure or may be due to environmental contamination from animals. The risk of injury and illness is dependent largely on the type of livestock. The risk of injury also depends on the particulars of animal behaviour (see also the articles in this chapter on specific animals). In addition, persons associated with animal husbandry are often more likely to consume products from the animals. Finally, the specific exposures depend on methods of handling livestock, which have emerged from geographical and social factors that vary across human society.

Hazards and Precautions

Ergonomic Risks

Personnel who work with cattle often have to stand, reach, bend or exert physical effort in sustained or unusual positions. Livestock workers do have an increased risk of joint pain of the back, hips and knees. There are several activities that place the livestock worker at ergonomic risk. For example, assisting with birthing of a large animal may put the farmworker in an unusual and strained position, whereas with a small animal, the worker may be required to work or lie in an inclement environment. Further, the worker may be injured by assisting animals who are ill and whose behaviour cannot be anticipated. More commonly, joint and back pain have to do with a repetitive motion, such as milking, during which the worker may crouch or kneel repeatedly.

Other cumulative trauma diseases are recognized in farmworkers, particularly livestock workers. These may be due to repetitive motion or frequent small injuries.

Solutions to reduce ergonomic risk include intensified educational efforts focused upon appropriate handling of animals, as well as engineering efforts to redesign the work environment and its tasks to accommodate animal and human factors.

Injuries

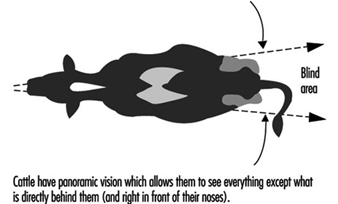

Animals are commonly recognized as agents of injury in surveys of injuries associated with agriculture. There are several postulated explanations for these observations. Close association between the worker and the animal, which often has unpredictable behaviour, puts the livestock worker at risk. Many livestock have superior size and strength. Injuries are often due to direct trauma from kicking, biting or crushing against a structure and often involve the worker’s lower extremity. The behaviour of workers may also contribute to risk of injury. Workers who penetrate the “flight zone” of livestock or who position themselves in livestock “blind spots” are at increased risk of injury resulting from flight reaction, butting, kicking and crushing.

Figure 1. Panoramic vision of cattle

Women and children are over-represented among injured livestock workers. This may be due to societal factors resulting in women and children doing more of the animal-related work, or it may be due to exaggerated size differences between the animals and worker or, in the case of children, use of handling techniques to which livestock are unaccustomed.

Specific interventions to prevent animal-associated injuries include intense educational efforts, selecting animals that are more compatible with humans, selecting workers who are less likely to agitate animals and engineering approaches that decrease the risk of exposure of humans to animals.

Zoonotic Diseases

Livestock rearing requires close association of workers and animals. Humans may become infected by organisms normally present on animals, which are rarely human pathogens. In addition, the tissues and behaviour associated with infected animals may expose workers who would experience few, if any, exposures if they were working with healthy livestock.

The relevant zoonotic diseases include numerous viruses, bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi and parasites (see table 1). Many zoonotic diseases, such as anthrax, tinea capitis or orf, are associated with skin contamination. In addition, contamination resulting from exposure to a diseased animal is a risk factor for rabies and tularaemia. Because livestock workers often are more likely to ingest under-treated animal products, such workers are at risk of diseases such as Campylobacter, cryptosporidiosis, salmonellosis, trichinosis or tuberculosis.

Table 1. Zoonotic diseases of livestock handlers

|

Disease |

Agent |

Animal |

Exposure |

|

Anthrax |

Bacteria |

Goats, other herbivores |

Handling hair, bone or other tissues |

|

Brucellosis |

Bacteria |

Cattle, swine, goats, sheep |

Contact with placenta and other contaminated tissues |

|

Campylobacter |

Bacteria |

Poultry, cattle |

Ingestion of contaminated food, water, milk |

|

Cryptosporidiosis |

Parasite |

Poultry, cattle, sheep, small mammals |

Ingestion of animal faeces |

|

Leptospirosis |

Bacteria |

Wild animals, swine, cattle, dogs |

Contaminated water on open skin |

|

Orf |

Virus |

Sheep, goats |

Direct contact with mucous membranes |

|

Psittacosis |

Chlamydia |

Parakeets, poultry, pigeons |

Inhaled desiccated droppings |

|

Q fever |

Rickettsia |

Cattle, goats, sheep |

Inhaled dust from contaminated tissues |

|

Rabies |

Virus |

Wild carnivores, dogs, cats, livestock |

Exposure of virus-laden saliva to breaks in skin |

|

Salmonellosis |

Bacteria |

Poultry, swine, cattle |

Ingestion of food from contaminated organisms |

|

Tinea capitis |

Fungus |

Dogs, cats, cattle |

Direct contact |

|

Trichinosis |

Roundworm |

Swine, dogs, cats, horses |

Eating poorly cooked flesh |

|

Tuberculosis, bovine |

Mycobacteria |

Cattle, swine |

Ingestion of unpasteurized milk; inhalation of airborne droplets |

|

Tularaemia |

Bacteria |

Wild animals, swine, dogs |

Inoculation from contaminated water or flesh |

The control of zoonotic diseases must focus on the route and source of exposure. Elimination of the source and/or interruption of the route are essential to disease control. For example, there must be proper disposal of the carcasses of diseased animals. Often, the human disease can be prevented by eliminating the disease in animals. Additionally, there should be adequate processing of animal products or tissues before use in the human food chain.

Some zoonotic diseases are treated in the livestock worker with antibiotics. However, routine prophylactic antibiotic usage on livestock may cause emergence of resistant organisms of general public health concern.

Blacksmithing

Blacksmithing (farrier work) involves primarily musculoskeletal and environmental injury. The manipulation of metal to be used in animal care, such as for horseshoes, does demand heavy work requiring substantial muscle activity to prepare the metal and position animal legs or feet. Furthermore, applying the created product, such as a horseshoe, to the animal in farrier work is an additional source of injury (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Blacksmith shoeing a horse in Switzerland

Often, the heat required to bend metal involves exposure to noxious gases. A recognized syndrome, metal fume fever, has a clinical picture similar to pulmonary infection and results from inhalation of fumes of nickel, magnesium, copper or other metals.

Adverse health effects associated with blacksmithing can be alleviated by working with adequate respiratory protection. Such respiratory devices include respirators or powered air-purifying respirators with cartridges and pre-filters capable of filtering acid gas/organic vapours and metal fumes. If the farrier work occurs in a fixed location, local exhaust ventilation should be installed for the forge. Engineering controls, which place distance or barricades between the animal and the worker, will reduce the risk of injury.

Animal Allergies

All animals possess antigens which are non-human and could therefore serve as potential allergens. In addition, livestock are often hosts for mites. Since there are a large number of potential animal allergies, recognition of a specific allergen requires careful and thorough disease and occupational histories. Even with such data, recognition of a specific allergen may be difficult.

The clinical expression of animal allergies may include an anaphylaxis-type picture, with hives, swelling, nasal discharge and asthma. In some patients, itching and nasal discharge may be the only symptoms.

Controlling exposure to animal allergies is a formidable task. Improved practices in animal husbandry and changes in livestock facility ventilation systems may make it less likely that the livestock handler will be exposed. However, there may be little that can be done, other than desensitization, to prevent the formation of specific allergens. In general, desensitizing a worker can be performed only if the specific allergen is adequately characterized.