Understanding what influences animal behaviour can help make for a safer work environment. Genetics and learned responses (operant conditioning) influence the way an animal behaves. Certain breeds of bulls are generally more docile than others (genetic influence). An animal that has balked or refused to enter an area, and is successful at not doing so, will likely refuse to do so the next time. On repeated tries it will get more agitated and dangerous. Animals respond to the way in which they are treated, and draw upon past experiences when reacting to a situation. Animals that are chased, slapped, kicked, hit, yelled at, frightened and so on, will naturally have a sense of fear when a human is near. Thus, it is important to do everything possible to make movement of animals successful on the first attempt and as free of stress as possible for the animal.

Domesticated animals living under fairly uniform conditions develop habits which are based on doing the same thing each day at a specific time. Confining bulls in a paddock and feeding them allows them to get used to humans and can be utilized with bull-confinement mating systems. Habits are also caused by regular changes in environmental conditions, such as temperature or humidity fluctuations when daylight turns to darkness. Animals are most active at the time of greatest change, which is at dawn or dusk, and least active either in the middle of the day or the middle of the night. This factor can be used to advantage in the movement or working of animals.

Like animals in the wild, domesticated animals can protect territories. During feeding, this can appear as aggressive behaviour. Studies have shown that feed distributed in large, unpredictable patches eliminates territorial behaviour in livestock. When feed is distributed uniformly or in predictable patterns, it may result in fighting by animals to secure the feed and exclude others. Territorial protection may also occur when a bull is permitted to remain with the herd. The bull may view the herd and the range they cover as his territory, which means he will defend it against perceived and real threats, such as humans, dogs and other animals. Introducing a new or strange bull of breeding age into the herd almost always results in fighting to establish the dominant male.

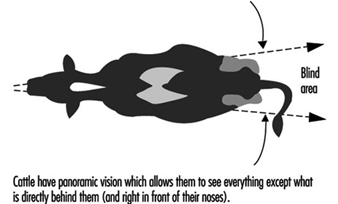

Bulls, due to having their eyes on the side of their head, have panoramic vision and very little depth perception. This means they can see about 270° around them, leaving a blind spot directly behind them and right in front of their noses (see figure 1). Sudden or unexpected movements from behind can “spook” the animal because it cannot determine the proximity or seriousness of the perceived threat. This can cause a “flight or fight” response in the animal. Because cattle have poor depth perception, they can also be easily frightened by shadows and movements outside of working or holding areas. Shadows falling within the working area may appear as a hole to the animal, which can cause it to balk. Cattle are colour blind, but do perceive colours as different shades of black and white.

Many animals are sensitive to noise (compared with humans), especially at high frequencies. Loud, abrupt noises, such as metal gates clanging shut, head chutes latching and/or humans yelling can cause stress in the animals.

Figure 1. Panoramic vision of cattle