Mineral exploration is the precursor to mining. Exploration is a high-risk, high-cost business that, if successful, results in the discovery of a mineral deposit that can be mined profitably. In 1992, US$1.2 billion was spent worldwide on exploration; this increased to almost US$2.7 billion in 1995. Many countries encourage exploration investment and competition is high to explore in areas with good potential for discovery. Almost without exception, mineral exploration today is carried out by interdisciplinary teams of prospectors, geologists, geophysicists and geochemists who search for mineral deposits in all terrain throughout the world.

Mineral exploration begins with a reconnaissance or generative stage and proceeds through a target evaluation stage, which, if successful, leads to advanced exploration. As a project progresses through the various stages of exploration, the type of work changes as do health and safety issues.

Reconnaissance field work is often conducted by small parties of geoscientists with limited support in unfamiliar terrain. Reconnaissance may comprise prospecting, geologic mapping and sampling, wide-spaced and preliminary geochemical sampling and geophysical surveys. More detailed exploration commences during the target testing phase once land is acquired through permit, concession, lease or mineral claims. Detailed field work comprising geologic mapping, sampling and geophysical and geochemical surveys requires a grid for survey control. This work frequently yields targets that warrant testing by trenching or drilling, entailing the use of heavy equipment such as back-hoes, power shovels, bulldozers, drills and, occasionally, explosives. Diamond, rotary or percussion drill equipment may be truck-mounted or may be hauled to the drill site on skids. Occasionally helicopters are used to sling drills between drill sites.

Some project exploration results will be sufficiently encouraging to justify advanced exploration requiring the collection of large or bulk samples to evaluate the economic potential of a mineral deposit. This may be accomplished through intensive drilling, although for many mineral deposits some form of trenching or underground sampling may be necessary. An exploration shaft, decline or adit may be excavated to gain underground access to the deposit. Although the actual work is carried out by miners, most mining companies will ensure that an exploration geologist is responsible for the underground sampling programme.

Health and Safety

In the past, employers seldom implemented or monitored exploration safety programmes and procedures. Even today, exploration workers frequently have a cavalier attitude towards safety. As a result, health and safety issues may be overlooked and not considered an integral part of the explorer’s job. Fortunately, many mining exploration companies now strive to change this aspect of the exploration culture by requiring that employees and contractors follow established safety procedures.

Exploration work is often seasonal. Consequently there are pressures to complete work within a limited time, sometimes at the expense of safety. In addition, as exploration work progresses to later stages, the number and variety of risks and hazards increase. Early reconnaissance field work requires only a small field crew and camp. More detailed exploration generally requires larger field camps to accommodate a greater number of employees and contractors. Safety issues—especially training on personal health issues, camp and worksite hazards, the safe use of equipment and traverse safety—become very important for geoscientists who may not have had previous field work experience.

Because exploration work is often carried out in remote areas, evacuation to a medical treatment centre may be difficult and may depend on weather or daylight conditions. Therefore, emergency procedures and communications should be carefully planned and tested before field work commences.

While outdoor safety may be considered common sense or “bush sense”, one should remember that what is considered common sense in one culture may not be so considered in another culture. Mining companies should provide exploration employees with a safety manual that addresses the issues of the regions where they work. A comprehensive safety manual can form the basis for camp orientation meetings, training sessions and routine safety meetings throughout the field season.

Preventing personal health hazards

Exploration work subjects employees to hard physical work that includes traversing terrain, frequent lifting of heavy objects, using potentially dangerous equipment and being exposed to heat, cold, precipitation and perhaps high altitude (see figure 1). It is essential that employees be in good physical condition and in good health when they begin field work. Employees should have up-to-date immunizations and be free of communicable diseases (e.g., hepatitis and tuberculosis) that may rapidly spread through a field camp. Ideally, all exploration workers should be trained and certified in basic first aid and wilderness first-aid skills. Larger camps or worksites should have at least one employee trained and certified in advanced or industrial first-aid skills.

Figure 1. Drilling in mountains in British Columbia, Canada, with a light Winkie drill

William S. Mitchell

Outdoor workers should wear suitable clothing that protects them from extremes of heat, cold and rain or snow. In regions with high levels of ultraviolet light, workers should wear a broad-brimmed hat and use a sunscreen lotion with a high sun protection factor (SPF) to protect exposed skin. When insect repellent is required, repellent that contains DEET (N,N-diethylmeta-toluamide) is most effective in preventing bites from mosquitoes. Clothing treated with permethrin helps protect against ticks.

Training. All field employees should receive training in such topics as lifting, the correct use of approved safety equipment (e.g., safety glasses, safety boots, respirators, appropriate gloves) and health precautions needed to prevent injury due to heat stress, cold stress, dehydration, ultraviolet light exposure, protection from insect bites and exposure to any endemic diseases. Exploration workers who take assignments in developing countries should educate themselves about local health and safety issues, including the possibility of kidnapping, robbery and assault.

Preventive measures for the campsite

Potential health and safety issues will vary with the location, size and type of work performed at a camp. Any field campsite should meet local fire, health, sanitation and safety regulations. A clean, orderly camp will help reduce accidents.

Location. A campsite should be established as close as safely possible to the worksite to minimize travel time and exposure to dangers associated with transportation. A campsite should be located away from any natural hazards and take into consideration the habits and habitat of wild animals that may invade a camp (e.g., insects, bears and reptiles). Whenever possible, camps should be near a source of clean drinking water (see figure 2). When working at very high altitude, the camp should be located at a lower elevation to help prevent altitude sickness.

Figure 2. Summer field camp, Northwest Territories, Canada

William S. Mitchell

Fire control and fuel handling. Camps should be set up so that tents or structures are well spaced to prevent or reduce the spread of fire. Fire-fighting equipment should be kept in a central cache and appropriate fire extinguishers kept in kitchen and office structures. Smoking regulations help prevent fires both in camp and in the field. All workers should participate in fire drills and know the plans for fire evacuation. Fuels should be accurately labelled to ensure that the correct fuel is used for lanterns, stoves, generators and so on. Fuel caches should be located at least 100 m from camp and above any potential flood or tide level.

Sanitation. Camps require a supply of safe drinking water. The source should be tested for purity, if required. When necessary, drinking water should be stored in clean, labelled containers separate from non-potable water. Food shipments should be examined for quality upon arrival and immediately refrigerated or stored in containers to prevent invasions from insects, rodents or larger animals. Handwashing facilities should be located near eating areas and latrines. Latrines must conform to public health standards and should be located at least 100 m away from any stream or shoreline.

Camp equipment, field equipment and machinery. All equipment (e.g., chain saws, axes, rock hammers, machetes, radios, stoves, lanterns, geophysical and geochemical equipment) should be kept in good repair. If firearms are required for personal safety from wild animals such as bears, their use must be strictly controlled and monitored.

Communication. It is important to establish regular communication schedules. Good communication increases morale and security and forms a basis for an emergency response plan.

Training. Employees should be trained in the safe use all equipment. All geophysicists and helpers should be trained to use ground (earth) geophysical equipment that may operate at high current or voltage. Additional training topics should include fire prevention, fire drills, fuel handling and firearms handing, when relevant.

Preventive measures at the worksite

The target testing and advanced stages of exploration require larger field camps and the use of heavy equipment at the worksite. Only trained workers or authorized visitors should be permitted onto worksites where heavy equipment is operating.

Heavy equipment. Only properly licensed and trained personnel may operate heavy equipment. Workers must be constantly vigilant and never approach heavy equipment unless they are certain the operator knows where they are, what they intend to do and where they intend to go.

Figure 3. Truck-mounted drill in Australia

Williams S. Mitchll

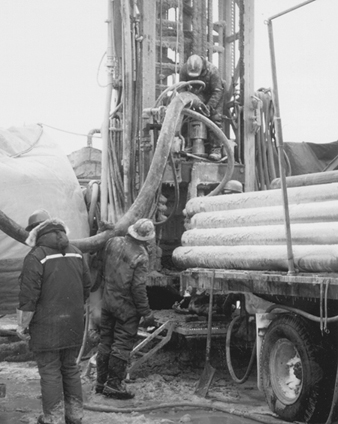

Drill rigs. Crews should be fully trained for the job. They must wear appropriate personal protective equipment (e.g., hard hats, steel-toed boots, hearing protection, gloves, goggles and dust masks) and avoid wearing loose clothing that may become caught in machinery. Drill rigs should comply with all safety requirements (e.g., guards that cover all moving parts of machinery, high pressure air hoses secured with clamps and safety chains) (see figure 3). Workers should be aware of slippery, wet, greasy, or icy conditions underfoot and the drill area kept as orderly as possible (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Reverse circulation drilling on a frozen lake in Canada

William S. Mitchell

Excavations. Pits and trenches should be constructed to meet safety guidelines with support systems or the sides cut back to 45º to deter collapse. Workers should never work alone or remain alone in a pit or trench, even for a short period of time, as these excavations collapse easily and may bury workers.

Explosives. Only trained and licensed personnel should handle explosives. Regulations for handling, storage and transportation of explosives and detonators should be carefully followed.

Preventive measures in traversing terrain

Exploration workers must be prepared to cope with the terrain and climate of their field area. The terrain may include deserts, swamps, forests, or mountainous terrain of jungle or glaciers and snowfields. Conditions may be hot or cold and dry or wet. Natural hazards may include lightning, bush fires, avalanches, mudslides or flash floods and so on. Insects, reptiles and/or large animals may present life-threatening hazards.

Workers must not take chances or place themselves in danger to secure samples. Employees should receive training in safe traversing procedures for the terrain and climate conditions where they work. They need survival training to recognize and combat hypothermia, hyperthermia and dehydration. Employees should work in pairs and carry enough equipment, food and water (or have access in an emergency cache) to enable them to spend an unexpected night or two out in the field if an emergency situation arises. Field workers should maintain routine communication schedules with the base camp. All field camps should have established and tested emergency response plans in case field workers need rescuing.

Preventive measures in transportation

Many accidents and incidents occur during transportation to or from an exploration worksite. Excessive speed and/or alcohol consumption while driving vehicles or boats are relevant safety issues.

Vehicles. Common causes of vehicle accidents include hazardous road and/or weather conditions, overloaded or incorrectly loaded vehicles, unsafe towing practices, driver fatigue, inexperienced drivers and animals or people on the road—especially at night. Preventive measures include following defensive driving techniques when operating any type of vehicle. Drivers and passengers of cars and trucks must use seatbelts and follow safe loading and towing procedures. Only vehicles that can safely operate in the terrain and weather conditions of the field area, e.g., 4-wheel drive vehicles, 2-wheel motor bikes, all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) or snowmobiles should be used (see figure 5). Vehicles must have regular maintenance and contain adequate equipment including survival gear. Protective clothing and a helmet are required when operating ATVs or 2-wheel motor bikes.

Figure 5. Winter field transportation in Canada

William S. Mitchell

Aircraft. Access to remote sites frequently depends on fixed wing aircraft and helicopters (see figure 6). Only charter companies with well-maintained equipment and a good safety record should be engaged. Aircraft with turbine engines are recommended. Pilots must never exceed the legal number of allowable flight hours and should never fly when fatigued or be asked to fly in unacceptable weather conditions. Pilots must oversee the proper loading of all aircraft and comply with payload restrictions. To prevent accidents, exploration workers must be trained to work safely around aircraft. They must follow safe embarkation and loading procedures. No one should walk in the direction of the propellers or rotor blades; they are invisible when moving. Helicopter landing sites should be kept free of loose debris that may become airborne projectiles in the downdraft of rotor blades.

Figure 6. Unloading field supplies from Twin Otter, Northwest Territories, Canada

William S. Mitchell

Slinging. Helicopters are often used to move supplies, fuel, drill and camp equipment. Some major hazards include overloading, incorrect use of or poorly maintained slinging equipment, untidy worksites with debris or equipment that may be blown about, protruding vegetation or anything that loads may snag on. In addition, pilot fatigue, lack of personnel training, miscommunication between parties involved (especially between the pilot and groundman) and marginal weather conditions increase the risks of slinging. For safe slinging and to prevent accidents, all parties must follow safe slinging procedures and be fully alert and well briefed with mutual responsibilities clearly understood. The sling cargo weight must not exceed the lifting capacity of the helicopter. Loads should be arranged so they are secure and nothing will slip out of the cargo net. When slinging with a very long line (e.g., jungle, mountainous sites with very tall trees), a pile of logs or large rocks should be used to weigh down the sling for the return trip because one should never fly with empty slings or lanyards dangling from the sling hook. Fatal accidents have occurred when unweighted lanyards have struck the helicopter tail or main rotor during flight.

Boats. Workers who rely on boats for field transportation on coastal waters, mountain lakes, streams or rivers may face hazards from winds, fog, rapids, shallows, and submerged or semi-submerged objects. To prevent boating accidents, operators must know and not exceed the limitations of their boat, their motor and their own boating capabilities. The largest, safest boat available for the job should be used. All workers should wear a good quality personal flotation device (PFD) whenever travelling and/or working in small boats. In addition, all boats must contain all legally required equipment plus spare parts, tools, survival and first aid equipment and always carry and use up-to-date charts and tide tables.