Summary of Generic Prevention and Control Strategies

Any organization which seeks to establish and maintain the best state of mental, physical and social wellbeing of its employees needs to have policies and procedures which comprehensively address health and safety. These policies will include a mental health policy with procedures to manage stress based on the needs of the organization and its employees. These will be regularly reviewed and evaluated.

There are a number of options to consider in looking at the prevention of stress, which can be termed as primary, secondary and tertiary levels of prevention and address different stages in the stress process (Cooper and Cartwright 1994). Primary prevention is concerned with taking action to reduce or eliminate stressors (i.e., sources of stress), and positively promoting a supportive and healthy work environment. Secondary prevention is concerned with the prompt detection and management of depression and anxiety by increasing self-awareness and improving stress management skills. Tertiary prevention is concerned with the rehabilitation and recovery process of those individuals who have suffered or are suffering from serious ill health as a result of stress.

To develop an effective and comprehensive organizational policy on stress, employers need to integrate these three approaches (Cooper, Liukkonen and Cartwright 1996).

Primary Prevention

First, the most effective way of tackling stress is to eliminate it at its source. This may involve changes in personnel policies, improving communication systems, redesigning jobs, or allowing more decision making and autonomy at lower levels. Obviously, as the type of action required by an organization will vary according to the kinds of stressor operating, any intervention needs to be guided by some prior diagnosis or stress audit to identify what these stressors are and whom they are affecting.

Stress audits typically take the form of a self-report questionnaire administered to employees on an organization- wide, site or departmental basis. In addition to identifying the sources of stress at work and those individuals most vulnerable to stress, the questionnaire usually measures levels of employee job satisfaction, coping behaviour, and physical and psychological health comparative to similar occupational groups and industries. Stress audits are an extremely effective way of directing organizational resources into areas where they are most needed. Audits also provide a means of regularly monitoring stress levels and employee health over time, and provide a base line whereby subsequent interventions can be evaluated.

Diagnostic instruments, such as the Occupational Stress Indicator (Cooper, Sloan and Williams 1988) are increasingly being used by organizations for this purpose. They are usually administered through occupational health and/or personnel/human resource departments in consultation with a psychologist. In smaller companies, there may be the opportunity to hold employee discussion groups or develop checklists which can be administered on a more informal basis. The agenda for such discussions/ checklists should address the following issues:

- job content and work scheduling

- physical working conditions

- employment terms and expectations of different employee groups within the organization

- relationships at work

- communication systems and reporting arrangements.

Another alternative is to ask employees to keep a stress diary for a few weeks in which they record any stressful events they encounter during the course of the day. Pooling this information on a group/departmental basis can be useful in identifying universal and persistent sources of stress.

Creating healthy and supportive networks/environments

Another key factor in primary prevention is the development of the kind of supportive organizational climate in which stress is recognized as a feature of modern industrial life and not interpreted as a sign of weakness or incompetence. Mental ill health is indiscriminate—it can affect anyone irrespective of their age, social status or job function. Therefore, employees should not feel awkward about admitting to any difficulties they encounter.

Organizations need to take explicit steps to remove the stigma often attached to those with emotional problems and maximize the support available to staff (Cooper and Williams 1994). Some of the formal ways in which this can be done include:

- informing employees of existing sources of support and advice within the organization, like occupational health

- specifically incorporating self-development issues within appraisal systems

- extending and improving the “people” skills of managers and supervisors so they that convey a supportive attitude and can more comfortably handle employee problems.

Most importantly, there has to be demonstrable commitment to the issue of stress and mental health at work from both senior management and unions. This may require a move to more open communication and the dismantling of cultural norms within the organization which inherently promote stress among employees (e.g., cultural norms which encourage employees to work excessively long hours and feel guilty about leaving “on time”). Organizations with a supportive organizational climate will also be proactive in anticipating additional or new stressors which may be introduced as a result of proposed changes. For example, restructuring, new technology and take steps to address this, perhaps by training initiatives or greater employee involvement. Regular communication and increased employee involvement and participation play a key role in reducing stress in the context of organizational change.

Secondary Prevention

Initiatives which fall into this category are generally focused on training and education, and involve awareness activities and skill- training programmes.

Stress education and stress management courses serve a useful function in helping individuals to recognize the symptoms of stress in themselves and others and to extend and develop their coping skills and abilities and stress resilience.

The form and content of this kind of training can vary immensely but often includes simple relaxation techniques, lifestyle advice and planning, basic training in time management, assertiveness and problem-solving skills. The aim of these programmes is to help employees to review the psychological effects of stress and to develop a personal stress-control plan (Cooper 1996).

This kind of programme can be beneficial to all levels of staff and is particularly useful in training managers to recognize stress in their subordinates and be aware of their own managerial style and its impact on those they manage. This can be of great benefit if carried out following a stress audit.

Health screening/health enhancement programmes

Organizations, with the cooperation of occupational health personnel, can also introduce initiatives which directly promote positive health behaviours in the workplace. Again, health promotion activities can take a variety of forms. They may include:

- the introduction of regular medical check-ups and health screening

- the design of “healthy” canteen menus

- the provision of on-site fitness facilities and exercise classes

- corporate membership or concessionary rates at local health and fitness clubs

- the introduction of cardiovascular fitness programmes

- advice on alcohol and dietary control (particularly cutting down on cholesterol, salt and sugar)

- smoking-cessation programmes

- advice on lifestyle management, more generally.

For organizations without the facilities of an occupational health department, there are external agencies that can provide a range of health-promotion programmes. Evidence from established health-promotion programmes in the United States have produced some impressive results (Karasek and Theorell 1990). For example, the New York Telephone Company’s Wellness Programme, designed to improve cardiovascular fitness, saved the organization $2.7 million in absence and treatment costs in one year alone.

Stress management/lifestyle programmes can be particularly useful in helping individuals to cope with environmental stressors which may have been identified by the organization, but which cannot be changed, e.g., job insecurity.

Tertiary Prevention

An important part of health promotion in the workplace is the detection of mental health problems as soon as they arise and the prompt referral of these problems for specialist treatment. The majority of those who develop mental illness make a complete recovery and are able to return to work. It is usually far more costly to retire a person early on medical grounds and re-recruit and train a successor than it is to spend time easing a person back to work. There are two aspects of tertiary prevention which organizations can consider:

Counselling

Organizations can provide access to confidential professional counselling services for employees who are experiencing problems in the workplace or personal setting (Swanson and Murphy 1991). Such services can be provided either by in-house counsellors or outside agencies in the form of an Employee Assistance Programme (EAP).

EAPs provide counselling, information and/or referral to appropriate counselling treatment and support services. Such services are confidential and usually provide a 24-hour contact line. Charges are normally made on a per capita basis calculated on the total number of employees and the number of counselling hours provided by the programme.

Counselling is a highly skilled business and requires extensive training. It is important to ensure that counsellors have received recognized counselling skills training and have access to a suitable environment which allows them to conduct this activity in an ethical and confidential manner.

Again, the provision of counselling services is likely to be particularly effective in dealing with stress as a result of stressors operating within the organization which cannot be changed (e.g., job loss) or stress caused by non-work related problems (e.g., bereavement, marital breakdown), but which nevertheless tend to spill over into work life. It is also useful in directing employees to the most appropriate sources of help for their problems.

Facilitating the return to work

For those employees who are absent from work as a result of stress, it has to be recognized that the return to work itself is likely to be a “stressful” experience. It is important that organizations are sympathetic and understanding in these circumstances. A “return to work” interview should be conducted to establish whether the individual concerned is ready and happy to return to all aspects of their job. Negotiations should involve careful liaison between the employee, line manager and doctor. Once the individual has made a partial or complete return to his or her duties, a series of follow-up interviews are likely to be useful to monitor their progress and rehabilitation. Again, the occupational health department can play an important role in the rehabilitation process.

The options outlined above should not be regarded as mutually exclusive but rather as being potentially complimentary. Stress- management training, health-promotion activities and counselling services are useful in extending the physical and psychological resources of the individual to help them to modify their appraisal of a stressful situation and cope better with experienced distress (Berridge, Cooper and Highley 1997). However, there are many potential and persistent sources of stress the individual is likely to perceive him- or herself as lacking the resource or positional power to change (e.g., the structure, management style or culture of the organization). Such stressors require organizational level intervention if their long-term dysfunctional impact on employee health is to be overcome satisfactorily. They can only be identified by a stress audit.

Burnout

Burnout is a type of prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job. It has been conceptualized as an individual stress experience embedded in a context of complex social relationships, and it involves the person’s conception of both self and others. As such, it has been an issue of particular concern for human services occupations where: (a) the relationship between providers and recipients is central to the job; and (b) the provision of service, care, treatment or education can be a highly emotional experience. There are several types of occupations that meet these criteria, including health care, social services, mental health, criminal justice and education. Even though these occupations vary in the nature of the contact between providers and recipients, they are similar in having a structured caregiving relationship centred around the recipient’s current problems (psychological, social and/or physical). Not only is the provider’s work on these problems likely to be emotionally charged, but solutions may not be easily forthcoming, thus adding to the frustration and ambiguity of the work situation. The person who works continuously with people under such circumstances is at greater risk from burnout.

The operational definition (and the corresponding research measure) that is most widely used in burnout research is a three-component model in which burnout is conceptualized in terms of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach 1993; Maslach and Jackson 1981/1986). Emotional exhaustion refers to feelings of being emotionally overextended and depleted of one’s emotional resources. Depersonalization refers to a negative, callous or excessively detached response to the people who are usually the recipients of one’s service or care. Reduced personal accomplishment refers to a decline in one’s feelings of competence and successful achievement in one’s work.

This multidimensional model of burnout has important theoretical and practical implications. It provides a more complete understanding of this form of job stress by locating it within its social context and by identifying the variety of psychological reactions that different workers can experience. Such differential responses may not be simply a function of individual factors (such as personality), but may reflect the differential impact of situational factors on the three burnout dimensions. For example, certain job characteristics may influence the sources of emotional stress (and thus emotional exhaustion), or the resources available to handle the job successfully (and thus personal accomplishment). This multidimensional approach also implies that interventions to reduce burnout should be planned and designed in terms of the particular component of burnout that needs to be addressed. That is, it may be more effective to consider how to reduce the likelihood of emotional exhaustion, or to prevent the tendency to depersonalize, or to enhance one’s sense of accomplishment, rather than to use a more unfocused approach.

Consistent with this social framework, the empirical research on burnout has focused primarily on situational and job factors. Thus, studies have included such variables as relationships on the job (clients, colleagues, supervisors) and at home (family), job satisfaction, role conflict and role ambiguity, job withdrawal (turnover, absenteeism), expectations, workload, type of position and job tenure, institutional policy and so forth. The personal factors that have been studied are most often demographic variables (sex, age, marital status, etc.). In addition, some attention has been given to personality variables, personal health, relations with family and friends (social support at home), and personal values and commitment. In general, job factors are more strongly related to burnout than are biographical or personal factors. In terms of antecedents of burnout, the three factors of role conflict, lack of control or autonomy, and lack of social support on the job, seem to be most important. The effects of burnout are seen most consistently in various forms of job withdrawal and dissatisfaction, with the implication of a deterioration in the quality of care or service provided to clients or patients. Burnout seems to be correlated with various self-reported indices of personal dysfunction, including health problems, increased use of alcohol and drugs, and marital and family conflicts. The level of burnout seems fairly stable over time, underscoring the notion that its nature is more chronic than acute (see Kleiber and Enzmann 1990; Schaufeli, Maslach and Marek 1993 for reviews of the field).

An issue for future research concerns possible diagnostic criteria for burnout. Burnout has often been described in terms of dysphoric symptoms such as exhaustion, fatigue, loss of self-esteem and depression. However, depression is considered to be context-free and pervasive across all situations, whereas burnout is regarded as job-related and situation-specific. Other symptoms include problems in concentration, irritability and negativism, as well as a significant decrease in work performance over a period of several months. It is usually assumed that burnout symptoms manifest themselves in “normal” persons who do not suffer from prior psychopathology or an identifiable organic illness. The implication of these ideas about possible distinctive symptoms of burnout is that burnout could be diagnosed and treated at the individual level.

However, given the evidence for the situational aetiology of burnout, more attention has been given to social, rather than personal, interventions. Social support, particularly from one’s peers, seems to be effective in reducing the risk of burnout. Adequate job training that includes preparation for difficult and stressful work-related situations helps develop people’s sense of self-efficacy and mastery in their work roles. Involvement in a larger community or action-oriented group can also counteract the helplessness and pessimism that are commonly evoked by the absence of long-term solutions to the problems with which the worker is dealing. Accentuating the positive aspects of the job and finding ways to make ordinary tasks more meaningful are additional methods for gaining greater self-efficacy and control.

There is a growing tendency to view burnout as a dynamic process, rather than a static state, and this has important implications for the proposal of developmental models and process measures. The research gains to be expected from this newer perspective should yield increasingly sophisticated knowledge about the experience of burnout, and will enable both individuals and institutions to deal with this social problem more effectively.

Mental Illness

Carles Muntaner and William W. Eaton

Introduction

Mental illness is one of the chronic outcomes of work stress that inflicts a major social and economic burden on communities (Jenkins and Coney 1992; Miller and Kelman 1992). Two disciplines, psychiatric epidemiology and mental health sociology (Aneshensel, Rutter and Lachenbruch 1991), have studied the effects of psychosocial and organizational factors of work on mental illness. These studies can be classified according to four different theoretical and methodological approaches: (1) studies of only a single occupation; (2) studies of broad occupational categories as indicators of social stratification; (3) comparative studies of occupational categories; and (4) studies of specific psychosocial and organizational risk factors. We review each of these approaches and discuss their implications for research and prevention.

Studies of a Single Occupation

There are numerous studies in which the focus has been a single occupation. Depression has been the focus of interest in recent studies of secretaries (Garrison and Eaton 1992), professionals and managers (Phelan et al. 1991; Bromet et al. 1990), computer workers (Mino et al. 1993), fire-fighters (Guidotti 1992), teachers (Schonfeld 1992), and “maquiladoras” (Guendelman and Silberg 1993). Alcoholism and drug abuse and dependence have been recently related to mortality among bus drivers (Michaels and Zoloth 1991) and to managerial and professional occupations (Bromet et al. 1990). Symptoms of anxiety and depression which are indicative of psychiatric disorder have been found among garment workers, nurses, teachers, social workers, offshore oil industry workers and young physicians (Brisson, Vezina and Vinet 1992; Fith-Cozens 1987; Fletcher 1988; McGrath, Reid and Boore 1989; Parkes 1992). The lack of a comparison group makes it difficult to determine the significance of this type of study.

Studies of Broad Occupational Categories as Indicators of Social Stratification

The use of occupations as indicators of social stratification has a long tradition in mental health research (Liberatos, Link and Kelsey 1988). Workers in unskilled manual jobs and lower-grade civil servants have shown high prevalence rates of minor psychiatric disorders in England (Rodgers 1991; Stansfeld and Marmot 1992). Alcoholism has been found to be prevalent among blue-collar workers in Sweden (Ojesjo 1980) and even more prevalent among managers in Japan (Kawakami et al. 1992). Failure to differentiate conceptually between effects of occupations per se from “lifestyle” factors associated with occupational strata is a serious weakness of this type of study. It is also true that occupation is an indicator of social stratification in a sense different from social class, that is, as the latter implies control over productive assets (Kohn et al. 1990; Muntaner et al. 1994). However, there have not been empirical studies of mental illness using this conceptualization.

Comparative Studies of Occupational Categories

Census categories for occupations constitute a readily available source of information that allows one to explore associations between occupations and mental illness (Eaton et al. 1990). Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study analyses of comprehensive occupational categories have yielded findings of a high prevalence of depression for professional, administrative support and household services occupations (Roberts and Lee 1993). In another major epidemiological study, the Alameda county study, high rates of depression were found among workers in blue-collar occupations (Kaplan et al. 1991). High 12-month prevalence rates of alcohol dependence among workers in the Unites States have been found in craft occupations (15.6%) and labourers (15.2%) among men, and in farming, forestry and fishing occupations (7.5%) and unskilled service occupations (7.2%) among women (Harford et al. 1992). ECA rates of alcohol abuse and dependence yielded high prevalence among transportation, craft and labourer occupations (Roberts and Lee 1993). Workers in the service sector, drivers and unskilled workers showed high rates of alcoholism in a study of the Swedish population (Agren and Romelsjo 1992). Twelve-month prevalence of drug abuse or dependence in the ECA study was higher among farming (6%), craft (4.7%), and operator, transportation and labourer (3.3%) occupations (Roberts and Lee 1993). The ECA analysis of combined prevalence for all psychoactive substance abuse or dependence syndromes (Anthony et al. 1992) yielded higher prevalence rates for construction labourers, carpenters, construction trades as a whole, waiters, waitresses and transportation and moving occupations. In another ECA analysis (Muntaner et al. 1991), as compared to managerial occupations, greater risk of schizophrenia was found among private household workers, while artists and construction trades were found at higher risk of schizophrenia (delusions and hallucinations), according to criterion A of the Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) (APA 1980).

Several ECA studies have been conducted with more specific occupational categories. In addition to specifying occupational environments more closely, they adjust for sociodemographic factors which might have led to spurious results in uncontrolled studies. High 12-month prevalence rates of major depression (above the 3 to 5% found in the general population (Robins and Regier 1990), have been reported for data entry keyers and computer equipment operators (13%) and typists, lawyers, special education teachers and counsellors (10%) (Eaton et al. 1990). After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, lawyers, teachers and counsellors had significantly elevated rates when compared to the employed population (Eaton et al. 1990). In a detailed analysis of 104 occupations, construction labourers, skilled construction trades, heavy truck drivers and material movers showed high rates of alcohol abuse or dependence (Mandell et al. 1992).

Comparative studies of occupational categories suffer from the same flaws as social stratification studies. Thus, a problem with occupational categories is that specific risk factors are bound to be missed. In addition, “lifestyle” factors associated with occupational categories remain a potent explanation for results.

Studies of Specific Psychosocial and Organizational Risk Factors

Most studies of work stress and mental illness have been conducted with scales from Karasek’s Demand/Control model (Karasek and Theorell 1990) or with measures derived from the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) (Cain and Treiman 1981). In spite of the methodological and theoretical differences underlying these systems, they measure similar psychosocial dimensions (control, substantive complexity and job demands) (Muntaner et al. 1993). Job demands have been associated with major depressive disorder among male power-plant workers (Bromet 1988). Occupations involving lack of direction, control or planning have been shown to mediate the relation between socioeconomic status and depression (Link et al. 1993). However, in one study the relationship between low control and depression was not found (Guendelman and Silberg 1993). The number of negative work-related effects, lack of intrinsic job rewards and organizational stressors such as role conflict and ambiguity have also been associated with major depression (Phelan et al. 1991). Heavy alcohol drinking and alcohol-related problems have been linked to working overtime and to lack of intrinsic job rewards among men and to job insecurity among women in Japan (Kawakami et al. 1993), and to high demands and low control among males in the United States (Bromet 1988). Also among US males, high psychological or physical demands and low control were predictive of alcohol abuse or dependence (Crum et al. 1995). In another ECA analysis, high physical demands and low skill discretion were predictive of drug dependence (Muntaner et al. 1995). Physical demands and job hazards were predictors of schizophrenia or delusions or hallucinations in three US studies (Muntaner et al. 1991; Link et al. 1986; Muntaner et al. 1993). Physical demands have also been associated with psychiatric disease in the Swedish population (Lundberg 1991). These investigations have the potential for prevention because specific, potentially malleable risk factors are the focus of study.

Implications for Research and Prevention

Future studies might benefit from studying the demographic and sociological characteristics of workers in order to sharpen their focus on the occupations proper (Mandell et al. 1992). When occupation is considered an indicator of social stratification, adjustment for non-work stressors should be attempted. The effects of chronic exposure to lack of democracy in the workplace need to be investigated (Johnson and Johansson 1991). A major initiative for the prevention of work-related psychological disorders has emphasized improving working conditions, services, research and surveillance (Keita and Sauter 1992; Sauter, Murphy and Hurrell 1990).

While some researchers maintain that job redesign can improve both productivity and workers’ health (Karasek and Theorell 1990), others have argued that a firm’s profit maximization goals and workers’ mental health are in conflict (Phelan et al. 1991; Muntaner and O’Campo 1993; Ralph 1983).

Musculoskeletal Disorders

There is growing evidence in the occupational health literature that psychosocial work factors may influence the development of musculoskeletal problems, including both low back and upper extremity disorders (Bongers et al. 1993). Psychosocial work factors are defined as aspects of the work environment (such as work roles, work pressure, relationships at work) that can contribute to the experience of stress in individuals (Lim and Carayon 1994; ILO 1986). This paper provides a synopsis of the evidence and underlying mechanisms linking psychosocial work factors and musculoskeletal problems with the emphasis on studies of upper extremity disorders among office workers. Directions for future research are also discussed.

An impressive array of studies from 1985 to 1995 had linked workplace psychosocial factors to upper extremity musculoskeletal problems in the office work environment (see Moon and Sauter 1996 for an extensive review). In the United States, this relationship was first suggested in an exploratory research by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (Smith et al. 1981). Results of this research indicated that video display unit (VDU) operators who reported less autonomy and role clarity and greater work pressure and management control over their work processes also reported more musculoskeletal problems than their counterparts who did not work with VDUs (Smith et al. 1981).

Recent studies employing more powerful inferential statistical techniques point more strongly to an effect of psychosocial work factors on upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders among office workers. For example, Lim and Carayon (1994) used structural analysis methods to examine the relationship between psychosocial work factors and upper extremity musculoskeletal discomfort in a sample of 129 office workers. Results showed that psychosocial factors such as work pressure, task control and production quotas were important predictors of upper extremity musculoskeletal discomfort, especially in the neck and shoulder regions. Demographic factors (age, gender, tenure with employer, hours of computer use per day) and other confounding factors (self-reports of medical conditions, hobbies and keyboard use outside work) were controlled for in the study and were not related to any of these problems.

Confirmatory findings were reported by Hales et al. (1994) in a NIOSH study of musculoskeletal disorders in 533 tele-communication workers from 3 different metropolitan cities. Two types of musculoskeletal outcomes were investigated: (1) upper extremity musculoskeletal symptoms determined by questionnaire alone; and (2) potential work-related upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders which were determined by physical examination in addition to the questionnaire. Using regression techniques, the study found that factors such as work pressure and little decision-making opportunity were associated both with intensified musculoskeletal symptoms and also with increased physical evidence of disease. Similar relationships have been observed in the industrial environment, but mainly for back pain (Bongers et al. 1993).

Researchers have suggested a variety of mechanisms underlying the relationship between psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal problems (Sauter and Swanson 1996; Smith and Carayon 1996; Lim 1994; Bongers et al. 1993). These mechanisms can be classified into four categories:

- psychophysiological

- behavioural

- physical

- perceptual.

Psychophysiological mechanisms

It has been demonstrated that individuals subject to stressful psychosocial working conditions also exhibit increased autonomic arousal (e.g., increased catecholomine secretion, increased heart rate and blood pressure, increased muscle tension etc.) (Frankenhaeuser and Gardell 1976). This is a normal and adaptive psychophysiological response which prepares the individual for action. However, prolonged exposure to stress may have a deleterious effect on musculoskeletal function as well as on health in general. For example, stress-related muscle tension may increase the static loading of muscles, thereby accelerating muscle fatigue and associated discomfort (Westgaard and Bjorklund 1987; Grandjean 1986).

Behavioural mechanisms

Individuals who are under stress may alter their work behaviour in a way that increases musculoskeletal strain. For example, psychological stress may result in greater application of force than necessary during typing or other manual tasks, leading to increased wear and tear on the musculoskeletal system.

Physical mechanisms

Psychosocial factors may influence the physical (ergonomic) demands of the job directly. For example, an increase in time pressure is likely to lead to an increase in work pace (i.e., increased repetition) and increased strain. Alternatively, workers who are given more control over their tasks may be able to adjust their tasks in ways that lead to reduced repetitiveness (Lim and Carayon 1994).

Perceptual mechanisms

Sauter and Swanson (1996) suggest that the relationship between biomechanical stressors (e.g., ergonomic factors) and the development of musculoskeletal problems is mediated by perceptual processes which are influenced by workplace psychosocial factors. For example, symptoms might become more evident in dull, routine jobs than in more engrossing tasks which more fully occupy the attention of the worker (Pennebaker and Hall 1982).

Additional research is needed to assess the relative importance of each of these mechanisms and their possible interactions. Further, our understanding of causal relationships between psychosocial work factors and musculoskeletal disorders would benefit from: (1) increased use of longitudinal study designs; (2) improved methods for assessing and disentangling psychosocial and physical exposures; and (3) improved measurement of musculoskeletal outcomes.

Still, the current evidence linking psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal disorders is impressive and suggests that psychosocial interventions probably play an important role in preventing musculoskeletal problems in the workplace. In this regard, several publications (NIOSH 1988; ILO 1986) provide directions for optimizing the psychosocial environment at work. As suggested by Bongers et al. (1993), special attention should be given to providing a supportive work environment, manageable workloads and increased worker autonomy. Positive effects of such variables were evident in a case study by Westin (1990) of the Federal Express Corporation. According to Westin, a programme of work reorganization to provide an “employee-supportive” work environment, improve communications and reduce work and time pressures was associated with minimal evidence of musculoskeletal health problems.

Cancer

Stress, the physical and/or psychological departure from a person’s stable equilibrium, can result from a large number of stressors, those stimuli that produce stress. For a good general view of stress and the most common job stressors, Levi’s discussion in this chapter of job stress theories is recommended.

In addressing the question of whether job stress can and does affect the epidemiology of cancer, we face limitations: a search of the literature located only one study on actual job stress and cancer in urban bus drivers (Michaels and Zoloth 1991) (and there are only few studies in which the question is considered more generally). We cannot accept the findings of that study, because the authors did not take into account either the effects of high density exhaust fumes or smoking. Further, one cannot carry over the findings from other diseases to cancer because the disease mechanisms are so vastly different.

Nevertheless, it is possible to describe what is known about the connections between more general life stressors and cancer, and further, one might reasonably apply those findings to the job situation. We differentiate relationships of stress to two outcomes: cancer incidence and cancer prognosis. The term incidence evidently means the occurrence of cancer. However, incidence is established either by the doctor’s clinical diagnosis or at autopsy. Since tumour growth is slow—1 to 20 years may elapse from the malignant mutation of one cell to the detection of the tumour mass—incidence studies include both initiation and growth. The second question, whether stress can affect prognosis, can be answered only in studies of cancer patients after diagnosis.

We distinguish cohort studies from case-control studies. This discussion focuses on cohort studies, where a factor of interest, in this case stress, is measured on a cohort of healthy persons, and cancer incidence or mortality is determined after a number of years. For several reasons, little emphasis is given to case-control studies, those which compare reports of stress, either current or before diagnosis, in cancer patients (cases) and persons without cancer (controls). First, one can never be sure that the control group is well-matched to the case group with respect to other factors that can influence the comparison. Secondly, cancer can and does produce physical, psychological and attitudinal changes, mostly negative, that can bias conclusions. Thirdly, these changes are known to result in an increase in the number of reports of stressful events (or of their severity) compared to reports by controls, thus leading to biased conclusions that patients experienced more, or more severe, stressful events than did controls (Watson and Pennebaker 1989).

Stress and Cancer Incidence

Most studies on stress and cancer incidence have been of the case-control sort, and we find a wild mix of results. Because, in varying degrees, these studies have failed to control contaminating factors, we don’t know which ones to trust, and they are ignored here. Among cohort studies, the number of studies showing that persons under greater stress did not experience more cancer than those under lesser stress exceeded by a large margin the number showing the reverse (Fox 1995). The results for several stressed groups are given.

- Bereaved spouses. In a Finnish study of 95,647 widowed persons their cancer death rate differed by only 3% from the rate of an age-equivalent non-widowed population over a period of five years. A study of causes of death during the 12 years following bereavement in 4,032 widowed persons in the state of Maryland showed no more cancer deaths among the widowed than among those still married—in fact, there were slightly fewer deaths than in the married. In England and Wales, the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys showed little evidence of an increase in cancer incidence after death of a spouse, and only a slight, non-significant increase in cancer mortality.

- Depressed mood. One study showed, but four studies did not, an excess of cancer mortality in the years following the measurement of a depressed mood (Fox 1989). This must be distinguished from hospitalizable depression, on which no well-controlled large-scale cohort studies have been done, and which clearly involves pathological depression, not applicable to the healthy working population. Even among this group of clinically depressed patients, however, most properly analysed smaller studies show no excess of cancer.

- A group of 2,020 men, aged 35 to 55, working in an electrical products factory in Chicago, was followed for 17 years after being tested. Those whose highest score on a variety of personality scales was reported on the depressed mood scale showed a cancer death rate 2.3 times that of men whose highest score was not referable to depressed mood. The researcher’s colleague followed the surviving cohort for another three years; the cancer death rate in the whole high-depressed-mood group had dropped to 1.3 times that of the control group. A second study of 6,801 adults in Alameda County, California, showed no excess cancer mortality among those with depressed mood when followed for 17 years. In a third study of 2,501 people with depressed mood in Washington County, Maryland, non-smokers showed no excess cancer mortality over 13 years compared to non-smoking controls, but there was an excess mortality among smokers. The results for smokers were later shown to be wrong, the error arising from a contaminating factor overlooked by the researchers. A fourth study, of 8,932 women at the Kaiser-Permanente Medical Center in Walnut Creek, California showed no excess of deaths due to breast cancer over 11 to 14 years among women with depressed mood at the time of measurement. A fifth study, done on a randomized national sample of 2,586 people in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the United States, showed no excess of cancer mortality among those showing depressed mood when measured on either of two independent mood scales. The combined findings of studies on 22,351 persons made up of disparate groups weigh heavily against the contrary findings of the one study on 2,020 persons.

- Other stressors. A study of 4,581 Hawaiian men of Japanese descent found no greater cancer incidence over a period of 10 years among those reporting high levels of stressful life events at the start of the study than those reporting lower levels. A study was carried out on 9,160 soldiers in the US Army who had been prisoners of war in the Pacific and European theatres in the Second World War and in Korea during the Korean conflict. The cancer death rate from 1946 to 1975 was either less than or no different from that found among soldiers matched by combat zone and combat activity who were not prisoners of war. In a study of 9,813 US Army personnel separated from the army during the year 1944 for “psychoneurosis”, a prima facie state of chronic stress, their cancer death rate over the period 1946 to 1969 was compared with that of a matched group not so diagnosed. The psychoneurotics’ rate was no greater than that of matched controls, and was, in fact, slightly lower, although not significantly so.

- Lowered levels of stress. There is evidence in some studies, but not in others, that higher levels of social support and social connections are associated with less cancer risk in the future. There are so few studies on this topic and the observed differences so unconvincing that the most a prudent reviewer can reasonably do is suggest the possibility of a true relationship. We need more solid evidence than that offered by the contradictory studies that have already been carried out.

Stress and cancer prognosis

This topic is of lesser interest because so few people of working age get cancer. Nevertheless, it ought to be mentioned that while survival differences have been found in some studies with regard to reported pre-diagnosis stress, other studies have shown no differences. One should, in judging these findings, recall the parallel ones showing that not only cancer patients, but also those with other ills, report more past stressful events than well people to a substantial degree because of the psychological changes brought about by the disease itself and, further, by the knowledge that one has the disease. With respect to prognosis, several studies have shown increased survival among those with good social support as against those with less social support. Perhaps more social support produces less stress, and vice versa. As regards both incidence and prognosis, however, the extant studies are at best only suggestive (Fox 1995).

Animal studies

It might be instructive to see what effects stress has had in experiments with animals. The results among well-conducted studies are much clearer, but not decisive. It was found that stressed animals with viral tumours show faster tumour growth and die earlier than unstressed animals. But the reverse is true of non-viral tumours, that is, those produced in the laboratory by chemical carcinogens. For these, stressed animals have fewer tumours and longer survival after the start of cancer than unstressed animals (Justice 1985). In industrial nations, however, only 3 to 4% of human malignancies are viral. All the rest are due to chemical or physical stimuli—smoking, x rays, industrial chemicals, nuclear radiation (e.g., that due to radon), excessive sunlight and so on. Thus, if one were to extrapolate from the findings for animals, one would conclude that stress is beneficial both to cancer incidence and survival. For a number of reasons one should not draw such an inference (Justice 1985; Fox 1981). Results with animals can be used to generate hypotheses relating to data describing humans, but cannot be the basis for conclusions about them.

Conclusion

In view of the variety of stressors that has been examined in the literature—long-term, short-term, more severe, less severe, of many types—and the preponderance of results suggesting little or no effect on later cancer incidence, it is reasonable to suggest that the same results apply in the work situation. As for cancer prognosis, too few studies have been done to draw any conclusions, even tentative ones, about stressors. It is, however, possible that strong social support may decrease incidence a little, and perhaps increase survival.

Gastrointestinal Problems

For many years, psychological stress has been assumed to contribute to the development of peptic ulcer disease (which involves ulcerating lesions in the stomach or duodenum). Researchers and health care providers have proposed more recently that stress might also be related to other gastrointestinal disorders such as non-ulcer dyspepsia (associated with symptoms of upper abdominal pain, discomfort and nausea persisting in the absence of any identifiable organic cause) and irritable bowel syndrome (defined as altered bowel habits plus abdominal pain in the absence of abnormal physical findings). In this article, the question is examined whether there is strong empirical evidence to suggest that psychological stress is a predisposing factor in the aetiology or exacerbation of these three gastrointestinal disorders.

Gastric and Duodenal Ulcer

There is clear evidence that humans who are exposed to acute stress in the context of severe physical trauma are prone to the development of ulcers. It is less obvious, however, whether life stressors per se (such as job demotion or the death of a close relative) precipitate or exacerbate ulcers. Lay people and health care practitioners alike commonly associate ulcers and stress, perhaps as a consequence of Alexander’s (1950) early psychoanalytic perspective on the topic. Alexander proposed that ulcer-prone persons suffered dependency conflicts in their relationships with others; coupled with a constitutional tendency toward chronic hypersecretion of gastric acid, dependency conflicts were believed to lead to ulcer formation. The psychoanalytic perspective has not received strong empirical support. Ulcer patients do not appear to display greater dependency conflicts than comparison groups, though ulcer patients do exhibit higher levels of anxiety, submissiveness and depression (Whitehead and Schuster 1985). The level of neuroticism characterizing some ulcer patients tends to be slight, however, and few could be considered as exhibiting psychopathological signs. In any case, studies of emotional disorder in ulcer patients have generally involved those persons who seek medical attention for their disorder; these individuals may not be representative of all ulcer patients.

The association between stress and ulcers follows from the assumption that certain persons are genetically predisposed to hypersecrete gastric acid, especially during stressful episodes. Indeed, about two thirds of duodenal ulcer patients show elevated pepsinogen levels; elevated levels of pepsinogen are also associated with peptic ulcer disease. Brady and associates’ (1958) studies of “executive” monkeys lent initial support to the idea that a stressful lifestyle or vocation may contribute to the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal disease. They found that monkeys required to perform a lever press task to avoid painful electric shocks (the presumed “executives”, which controlled the stressor) developed more gastric ulcers than comparison monkeys that passively received the same number and intensity of shocks. The analogy to the hard-driving businessman was very cogent for a time. Unfortunately, their results were confounded with anxiety; anxious monkeys were more likely to be assigned to the “executive” role in Brady’s laboratory because they learned the lever press task quickly. Efforts to replicate their results, using random assignment of subjects to conditions, have failed. Indeed, evidence shows that animals who lack control over environmental stressors develop ulcers (Weiss 1971). Human ulcer patients also tend to be shy and inhibited, which runs counter to the stereotype of the ulcer-prone hard-driving businessman. Finally, animal models are of limited utility because they focus on the development of gastric ulcers, while most ulcers in humans occur in the duodenum. Laboratory animals rarely develop duodenal ulcers in response to stress.

Experimental studies of the physiological reactions of ulcer patients versus normal subjects to laboratory stressors do not uniformly show excessive reactions in the patients. The premise that stress leads to increased acid secretion which, in turn, leads to ulceration, is problematic when one realizes that psychological stress usually produces a response from the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system inhibits, rather than enhances, the gastric secretion that is mediated via the splanchnic nerve. Besides hypersecretion other factors in the aetiology of ulcer have been proposed, namely, rapid gastric emptying, inadequate secretion of bicarbonate and mucus, and infection. Stress could potentially affect these processes though evidence is lacking.

Ulcers have been reported to be more common during wartime, but methodological problems in these studies necessitate caution. A study of air traffic controllers is sometimes cited as evidence supporting the role of psychological stress for the development of ulcers (Cobb and Rose 1973). Although air traffic controllers were significantly more likely than a control group of pilots to report symptoms typical of ulcer, the incidence of confirmed ulcer among the air traffic controllers was not elevated above the base rate of ulcer occurrence in the general population.

Studies of acute life events also present a confusing picture of the relationship between stress and ulcer (Piper and Tennant 1993). Many investigations have been conducted, though most of these studies employed small samples and were cross-sectional or retrospective in design. The majority of studies did not find that ulcer patients incurred more acute life events than community controls or patients with conditions in which stress is not implicated, such as gallstones or renal stones. However, ulcer patients reported more chronic stressors involving personal threat or goal frustration prior to the onset or recrudescence of ulcer. In two prospective studies, reports of subjects being under stress or having family problems at baseline levels predicted subsequent development of ulcers. Unfortunately, both prospective studies used single-item scales to measure stress. Other research has shown that slow healing of ulcers or relapse was associated with higher stress levels, but the stress indices used in these studies were unvalidated and may have been confounded with personality factors.

In summary, evidence for the role of stress in ulcer causation and exacerbation is limited. Large-scale population-based prospective studies of the occurrence of life events are needed which use validated measures of acute and chronic stress and objective indicators of ulcer. At this point, evidence for an association between psychological stress and ulcer is weak.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has been considered a stress- related disorder in the past, in part because the physiological mechanism of the syndrome is unknown and because a large proportion of IBS sufferers report that stress caused a change in their bowel habits. As in the ulcer literature, it is difficult to evaluate the value of retrospective accounts of stressors and symptoms among IBS patients. In an effort to explain their discomfort, ill persons may mistakenly associate symptoms with stressful life events. Two recent prospective studies shed more light on the subject, and both found a limited role for stressful events in the occurrence of IBS symptoms. Whitehead et al. (1992) had a sample of community residents suffering from IBS symptoms report life events and IBS symptoms at three-month intervals. Only about 10% of the variance in bowel symptoms among these residents could be attributed to stress. Suls, Wan and Blanchard (1994) had IBS patients keep diary records of stressors and symptoms for 21 successive days. They found no consistent evidence that daily stressors increased the incidence or severity of IBS symptomatology. Life stress appears to have little effect on acute changes in IBS.

Non-Ulcer Dyspepsia

The symptoms of non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) include bloating and fullness, belching, borborygmi, nausea and heartburn. In one retrospective study, NUD patients reported more acute life events and more highly threatening chronic difficulties compared to healthy community members, but other investigations failed to find a relationship between life stress and functional dyspepsia. NUD cases also show high levels of psychopathology, notably anxiety disorders. In the absence of prospective studies of life stress, few conclusions can be made (Bass 1986; Whitehead 1992).

Conclusions

Despite considerable empirical attention, no verdict has yet been reached on the relationship between stress and the development of ulcers. Contemporary gastroenterologists have focused mainly on heritable pepsinogen levels, inadequate secretion of bicarbonate and mucus, and Heliobacter pylori infection as causes of ulcer. If life stress plays a role in these processes, its contribution is probably weak. Though fewer studies address the role of stress in IBS and NUD, evidence for a connection to stress is also weak here. For all three disorders, there is evidence that anxiety is higher among patients compared to the general population, at least among those persons who refer themselves for medical care (Whitehead 1992). Whether this is a precursor or a consequence of gastrointestinal disease has not been definitively determined, although the latter opinion seems to be more likely to be true. In current practice, ulcer patients receive pharmacological treatment, and psychotherapy is rarely recommended. Anti-anxiety drugs are commonly prescribed to IBS and NUD patients, probably because the physiological origins of these disorders are still unknown. Stress management has been employed with IBS patients with some success (Blanchard et al. 1992) although this patient group also responds to placebo treatments quite readily. Finally, patients experiencing ulcer, IBS or NUD may well be frustrated by assumptions from family members, friends and practitioners alike that their condition was produced by stress.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Töres Theorell and Jeffrey V. Johnson

The scientific evidence suggesting that exposure to job stress increases the risk for cardiovascular disease increased substantially beginning in the mid-1980s (Gardell 1981; Karasek and Theorell 1990; Johnson and Johansson 1991). Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in economically developed societies, and contributes to increasing medical care costs. Diseases of the cardiovascular system include coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertensive disease, cerebrovascular disease and other disorders of the heart and circulatory system.

Most manifestations of coronary heart disease are caused partly by narrowing of the coronary arteries due to atherosclerosis. Coronary atherosclerosis is known to be influenced by a number of individual factors including: family history, dietary intake of saturated fat, high blood pressure, cigarette smoking and physical exercise. Except for heredity, all these factors could be influenced by the work environment. A poor work environment may decrease the willingness to stop smoking and adopt a healthy lifestyle. Thus, an adverse work environment could influence coronary heart disease via its effects on the classical risk factors.

There are also direct effects of stressful work environments on neurohormonal elevations as well as on heart metabolism. A combination of physiological mechanisms, shown to be related to stressful work activities, may increase the risk of myocardial infarction. The elevation of energy-mobilizing hormones, which increase during periods of excessive stress, may make the heart more vulnerable to the actual death of the muscle tissue. Conversely, energy-restoring and repairing hormones which protect the heart muscle from the adverse effects of energy-mobilizing hormones, decrease during periods of stress. During emotional (and physical) stress the heart beats faster and harder over an extended period of time, leading to excessive oxygen consumption in the heart muscle and the increased possibility of a heart attack. Stress may also disturb the cardiac rhythm of the heart. A disturbance associated with a fast heart rhythm is called tachyarrhythmia. When the heart rate is so fast that the heartbeat becomes inefficient a life-threatening ventricular fibrillation may result.

Early epidemiological studies of psychosocial working conditions associated with CVD suggested that high levels of work demands increased CHD risk. For example a prospective study of Belgian bank employees found that those in a privately owned bank had a significantly higher incidence of myocardial infarction than workers in public banks, even after adjustment was made for biomedical risk factors (Komitzer et al. 1982). This study indicated a possible relationship between work demands (which were higher in the private banks) and risk of myocardial infarction. Early studies also indicated a higher incidence of myocardial infarction among lower level employees in large companies (Pell and d’Alonzo 1963). This raised the possibility that psychosocial stress may not primarily be a problem for people with a high degree of responsibility, as had been assumed previously.

Since the early 1980s, many epidemiological studies have examined the specific hypothesis suggested by the Demand/ Control model developed by Karasek and others (Karasek and Theorell 1990; Johnson and Johansson 1991). This model states that job strain results from work organizations that combine high- performance demands with low levels of control over how the work is to be done. According to the model, work control can be understood as “job decision latitude”, or the task-related decision-making authority permitted by a given job or work organization. This model predicts that those workers who are exposed to high demand and low control over an extended period of time will have a higher risk of neurohormonal arousal which may result in adverse pathophysiological effects on the CVD system—which could eventually lead to increased risk of atherosclerotic heart disease and myocardial infarction.

Between 1981 and 1993, the majority of the 36 studies that examined the effects of high demands and low control on cardiovascular disease found significant and positive associations. These studies employed a variety of research designs and were performed in Sweden, Japan, the United States, Finland and Australia. A variety of outcomes was examined including CHD morbidity and mortality, as well as CHD risk factors including blood pressure, cigarette smoking, left ventricular mass index and CHD symptoms. Several recent review papers summarize these studies (Kristensen 1989; Baker et al. 1992; Schnall, Landsbergis and Baker 1994; Theorell and Karasek 1996). These reviewers note that the epidemiological quality of these studies is high and, moreover, that the stronger study designs have generally found greater support for the Demand/Control models. In general the adjustment for standard risk factors for cardiovascular disease does not eliminate nor significantly reduce the magnitude of the association between the high demand/low control combination and the risk of cardiovascular disease.

It is important to note, however, that the methodology in these studies varied considerably. The most important distinction is that some studies used the respondent’s own descriptions of their work situations, whereas others used an ‘average score’ method based on aggregating the responses of a nationally representative sample of workers within their respective job title groups. Studies utilizing self-reported work descriptions showed higher relative risks (2.0–4.0 versus 1.3–2.0). Psychological job demands were shown to be relatively more important in studies utilizing self-reported data than in studies utilizing aggregated data. The work control variables were more consistently found to be associated with excess CVD risk regardless of which exposure method was used.

Recently, work-related social support has been added to the demand-control formulation and workers with high demands, low control and low support, have been shown to have over a twofold risk for CVD morbidity and mortality compared to those with low demands, high control and high support (Johnson and Hall 1994). Currently efforts are being made to examine sustained exposure to demands, control and support over the course of the “psychosocial work career”. Descriptions of all the occupations during the whole work career are obtained for the participants and occupational scores are used for a calculation of the total lifetime exposure. The “total job control exposure” in relation to cardiovascular mortality incidence in working Swedes was studied and even after adjustment was made for age, smoking habits, exercise, ethnicity, education and social class, low total job control exposure was associated with a nearly twofold risk of dying a cardiovascular death over a 14-year follow-up period (Johnson et al. 1996).

A model similar to the Demand/Control model has been developed and tested by Siegrist and co-workers 1990 that uses “effort” and “social reward” as the crucial dimensions, the hypothesis being that high effort without social reward leads to increasing risk of cardiovascular disease. In a study of industrial workers it was shown that combinations of high effort and lack of reward predicted increased myocardial infarction risk independently of biomedical risk factors.

Other aspects of work organization, such as shift work, have also been shown to be associated with CVD risk. Constant rotation between night and day work has been found to be associated with increased risk of developing a myocardial infarction (Kristensen 1989; Theorell 1992).

Future research in this area particularly needs to focus on specifying the relationship between work stress exposure and CVD risk across different class, gender and ethnic groups.

Immunological Reactions

When a human being or an animal is subjected to a psychological stress situation, there is a general response involving psychological as well as somatic (bodily) responses. This is a general alarm response, or general activation or wake-up call, which affects all physiological responses, including the musculoskeletal system, the vegetative system (the autonomic system), the hormones and also the immune system.

Since the 1960s, we have been learning how the brain, and through it, psychological factors, regulates and influences all physiological processes, whether directly or indirectly. Previously it was held that large and essential parts of our physiology were regulated “unconsciously,” or not by brain processes at all. The nerves that regulate the gut, glands and the cardiovascular system were “autonomic”, or independent of the central nervous system (CNS); similarly, the hormones and the immune system were beyond central nervous control. However, the autonomic nervous system is regulated by the limbic structures of the brain, and may be brought under direct instrumental control through classical and instrumental learning procedures. The fact that the central nervous system controls endocrinological processes is also well established.

The last development to undercut the view that the CNS was isolated from many physiological processes was the evolution of psychoimmunology. It has now been demonstrated that the interaction of the brain (and psychological processes), may influence immune processes, either via the endocrine system or by direct innervation of lymphoid tissue. The white blood cells themselves may also be influenced directly by signal molecules from nervous tissue. Depressed lymphocyte function has been demonstrated to follow bereavement (Bartrop et al. 1977), and conditioning of the immune-suppressive response in animals (Cohen et al. 1979) and psychological processes were shown to have effects bearing on animal survival (Riley 1981); these discoveries were milestones in the development of psychoimmunology.

It is now well established that psychological stress produces changes in the level of antibodies in the blood, and in the level of many of the white blood cells. A brief stress period of 30 minutes may produce significant increases in lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Following more long-lasting stress situations, changes are also found in the other components of the immune system. Changes have been reported in the counts of almost all types of white blood cell and in the levels of immunoglobulins and their complements; the changes also affect important elements of the total immune response and the “immune cascade” as well. These changes are complex and seem to be bidirectional. Both increases and decreases have been reported. The changes seem to depend not only on the stress-inducing situation, but on also what type of coping and defence mechanisms the individual is using to handle this situation. This is particularly clear when the effects of real long-lasting stress situations are studied, for instance those associated with the job or with difficult life situations (“life stressors”). Highly specific relationships between coping and defence styles and several subsets of immune cells (number of lympho-, leuko- and monocytes; total T cells and NK cells) have been described (Olff et al. 1993).

The search for immune parameters as markers for long-lasting, sustained stress has not been all that successful. Since the relationships between immunoglobulins and stress factors have been demonstrated to be so complex, there is, understandably, no simple marker available. Such relationships as have been found are sometimes positive, sometimes negative. As far as psycho-logical profiles are concerned, to some extent the correlation matrix with one and the same psychological battery shows different patterns, varying from one occupational group to another (Endresen et al. 1991). Within each group, the patterns seem stable over long periods of time, up to three years. It is not known whether there are genetic factors that influence the highly specific relationships between coping styles and immune responses; if so, the manifestions of these factors must be highly dependent on interaction with life stressors. Also, it is not known whether it is possible to follow an individual’s stress level over a long period, given that the individual’s coping, defence and immune response style is known. This type of research is being pursued with highly selected personnel, for instance astronauts.

There may be a major flaw in the basic argument that immunoglobulins can be used as valid health risk markers. The original hypothesis was that low levels of circulating immunoglobulins might signal a low resistance and low immune competence. However, low values may not signal low resistance: they may only signal that this particular individual has not been challenged by infectious agents for a while—in fact, they may signal an extraordinary degree of health. The low values sometimes reported from returning astronauts and Antarctic personnel may not be a signal of stress, but only of the low levels of bacterial and viral challenge in the environment they have left.

There are many anecdotes in the clinical literature suggesting that psychological stress or critical life events can have an impact on the course of serious and non-serious illness. In the opinion of some, placebos and “alternative medicine” may exert their effects through psychoimmunological mechanisms. There are claims that reduced (and sometimes increased) immune competence should lead to increased susceptibility to infections in animals and in humans, and to inflammatory states like rheumatoid arthritis as well. It has been demonstrated convincingly that psychological stress affects the immune response to various types of inoculations. Students under examination stress report more symptoms of infectious illness in this period, which coincides with poorer cellular immune control (Glaser et al. 1992). There are also some claims that psychotherapy, in particular cognitive stress-management training, together with physical training, may affect the antibody response to viral infection.

There are also some positive findings with regard to cancer development, but only a few. The controversy over the claimed relationship between personality and cancer susceptibility has not been solved. Replications should be extended to include measures of immune responses to other factors, including lifestyle factors, which may be related to psychology, but the cancer effect may be a direct consequence of the lifestyle.

There is ample evidence that acute stress alters immune functions in human subjects and that chronic stress may also affect these functions. But to what extent are these changes valid and useful indicators of job stress? To what extent are immune changes—if they occur—a real health risk factor? There is no consensus in the field as of the time of this writing (1995).

Sound clinical trials and sound epidemiological research are required to advance in this field. But this type of research requires more funds than are available to the researchers. This work also requires an understanding of the psychology of stress, which is not always available to immunologists, and a profound understanding of how the immune system operates, which is not always available to psychologists.

Well-being Outcomes

Jobs can have a substantial impact on the affective well-being of job holders. In turn, the quality of workers’ well-being on the job influences their behaviour, decision making and interactions with colleagues, and spills over into family and social life as well.

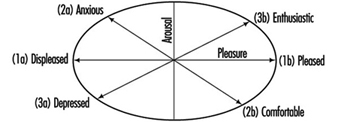

Research in many countries has pointed to the need to define the concept in terms of two separate dimensions that may be viewed as independent of each other (Watson, Clark and Tellegen 1988; Warr 1994). These dimensions may be referred to as “pleasure” and “arousal”. As illustrated in figure 1, a particular degree of pleasure or displeasure may be accompanied by high or low levels of mental arousal, and mental arousal may be either pleasurable or unpleasurable. This is indicated in terms of the three axes of well-being which are suggested for measurement: displeasure-to-pleasure, anxiety-to-comfort, and depression-to-enthusiasm.

Figure 1. Three principal axes for the measurement of affective well-being

Job-related well-being has often been measured merely along the horizontal axis, extending from “feeling bad” to “feeling good”. The measurement is usually made with reference to a scale of job satisfaction, and data are obtained by workers’ indicating their agreement or disagreement with a series of statements describing their feelings about their jobs. However, job satisfaction scales do not take into account differences in mental arousal, and are to that extent relatively insensitive. Additional forms of measurement are also needed, in terms of the other two axes in the figure.

When low scores on the horizontal axis are accompanied by raised mental arousal (upper left quadrant), low well-being is typically evidenced in the forms of anxiety and tension; however, low pleasure in association with low mental arousal (lower left) is observable as depression and associated feelings. Conversely, high job-related pleasure may be accompanied by positive feelings that are characterized either by enthusiasm and energy (3b) or by psychological relaxation and comfort (2b). This latter distinction is sometimes described in terms of motivated job satisfaction (3b) versus resigned, apathetic job satisfaction (2b).

In studying the impact of organizational and psychosocial factors on employee well-being, it is desirable to examine all three of the axes. Questionnaires are widely used for this purpose. Job satisfaction (1a to 1b) may be examined in two forms, sometimes referred to as “facet-free” and “facet-specific” job satisfaction. Facet-free, or overall, job satisfaction is an overarching set of feelings about one’s job as a whole, whereas facet-specific satisfactions are feelings about particular aspects of a job. Principal facets include pay, working conditions, one’s supervisor and the nature of the work undertaken.

These several forms of job satisfaction are positively intercorrelated, and it is sometimes appropriate merely to measure overall, facet-free satisfaction, rather than to examine separate, facet-specific satisfactions. A widely used general question is “On the whole, how satisfied are you with the work you do?”. Commonly used responses are very dissatisfied, a little dissatisfied, moderately satisfied, very satisfied and extremely satisfied, and are designated by scores from 1 to 5 respectively. In national surveys it is usual to find that about 90% of employees report themselves as satisfied to some degree, and a more sensitive measuring instrument is often desirable to yield more differentiated scores.

A multi-item approach is usually adopted, perhaps covering a range of different facets. For instance, several job satisfaction questionnaires ask about a person’s satisfaction with facets of the following kinds: the physical work conditions; the freedom to choose your own method of working; your fellow workers; the recognition you get for good work; your immediate boss; the amount of responsibility you are given; your rate of pay; your opportunity to use your abilities; relations between managers and workers; your workload; your chance of promotion; the equipment you use; the way your firm is managed; your hours of work; the amount of variety in your job; and your job security. An average satisfaction score may be calculated across all the items, responses to each item being scored from 1 to 5, for instance (see the preceding paragraph). Alternatively, separate values can be computed for “intrinsic satisfaction” items (those dealing with the content of the work itself) and “extrinsic satisfaction” items (those referring to the context of the work, such as colleagues and working conditions).

Self-report scales which measure axes two and three have often covered only one end of the possible distribution. For example, some scales of job-related anxiety ask about a worker’s feelings of tension and worry when on the job (2a), but do not in addition test for more positive forms of affect on this axis (2b). Based on studies in several settings (Watson, Clark and Tellegen 1988; Warr 1990), a possible approach is as follows.

Axes 2 and 3 may be examined by putting this question to workers: “Thinking of the past few weeks, how much of the time has your job made you feel each of the following?”, with response options of never, occasionally, some of the time, much of the time, most of the time, and all the time (scored from 1 to 6 respectively). Anxiety-to-comfort ranges across these states: tense, anxious, worried, calm, comfortable and relaxed. Depression-to-enthusiasm covers these states: depressed, gloomy, miserable, motivated, enthusiastic and optimistic. In each case, the first three items should be reverse-scored, so that a high score always reflects high well-being, and the items should be mixed randomly in the questionnaire. A total or average score can be computed for each axis.

More generally, it should be noted that affective well-being is not determined solely by a person’s current environment. Although job characteristics can have a substantial effect, well-being is also a function of some aspects of personality; people differ in their baseline well-being as well as in their reactions to particular job characteristics.

Relevant personality differences are usually described in terms of individuals’ continuing affective dispositions. The personality trait of positive affectivity (corresponding to the upper right-quadrant) is characterized by generally optimistic views of the future, emotions which tend to be positive and behaviours which are relatively extroverted. On the other hand, negative affectivity (corresponding to the upper left-hand quadrant) is a disposition to experience negative emotional states. Individuals with high negative affectivity tend in many situations to feel nervous, anxious or upset; this trait is sometimes measured by means of personality scales of neuroticism. Positive and negative affectivities are regarded as traits, that is, they are relatively constant from one situation to another, whereas a person’s well-being is viewed as an emotional state which varies in response to current activities and environmental influences.

Measures of well-being necessarily identify both the trait (the affective disposition) and the state (current affect). This fact should be borne in mind in examining people’s well-being score on an individual basis, but it is not a substantial problem in studies of the average findings for a group of employees. In longitudinal investigations of group scores, observed changes in well-being can be attributed directly to changes in the environment, since every person’s baseline well-being is held constant across the occasions of measurement; and in cross-sectional group studies an average affective disposition is recorded as a background influence in all cases.