Jobs can have a substantial impact on the affective well-being of job holders. In turn, the quality of workers’ well-being on the job influences their behaviour, decision making and interactions with colleagues, and spills over into family and social life as well.

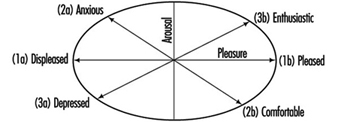

Research in many countries has pointed to the need to define the concept in terms of two separate dimensions that may be viewed as independent of each other (Watson, Clark and Tellegen 1988; Warr 1994). These dimensions may be referred to as “pleasure” and “arousal”. As illustrated in figure 1, a particular degree of pleasure or displeasure may be accompanied by high or low levels of mental arousal, and mental arousal may be either pleasurable or unpleasurable. This is indicated in terms of the three axes of well-being which are suggested for measurement: displeasure-to-pleasure, anxiety-to-comfort, and depression-to-enthusiasm.

Figure 1. Three principal axes for the measurement of affective well-being

Job-related well-being has often been measured merely along the horizontal axis, extending from “feeling bad” to “feeling good”. The measurement is usually made with reference to a scale of job satisfaction, and data are obtained by workers’ indicating their agreement or disagreement with a series of statements describing their feelings about their jobs. However, job satisfaction scales do not take into account differences in mental arousal, and are to that extent relatively insensitive. Additional forms of measurement are also needed, in terms of the other two axes in the figure.

When low scores on the horizontal axis are accompanied by raised mental arousal (upper left quadrant), low well-being is typically evidenced in the forms of anxiety and tension; however, low pleasure in association with low mental arousal (lower left) is observable as depression and associated feelings. Conversely, high job-related pleasure may be accompanied by positive feelings that are characterized either by enthusiasm and energy (3b) or by psychological relaxation and comfort (2b). This latter distinction is sometimes described in terms of motivated job satisfaction (3b) versus resigned, apathetic job satisfaction (2b).

In studying the impact of organizational and psychosocial factors on employee well-being, it is desirable to examine all three of the axes. Questionnaires are widely used for this purpose. Job satisfaction (1a to 1b) may be examined in two forms, sometimes referred to as “facet-free” and “facet-specific” job satisfaction. Facet-free, or overall, job satisfaction is an overarching set of feelings about one’s job as a whole, whereas facet-specific satisfactions are feelings about particular aspects of a job. Principal facets include pay, working conditions, one’s supervisor and the nature of the work undertaken.

These several forms of job satisfaction are positively intercorrelated, and it is sometimes appropriate merely to measure overall, facet-free satisfaction, rather than to examine separate, facet-specific satisfactions. A widely used general question is “On the whole, how satisfied are you with the work you do?”. Commonly used responses are very dissatisfied, a little dissatisfied, moderately satisfied, very satisfied and extremely satisfied, and are designated by scores from 1 to 5 respectively. In national surveys it is usual to find that about 90% of employees report themselves as satisfied to some degree, and a more sensitive measuring instrument is often desirable to yield more differentiated scores.

A multi-item approach is usually adopted, perhaps covering a range of different facets. For instance, several job satisfaction questionnaires ask about a person’s satisfaction with facets of the following kinds: the physical work conditions; the freedom to choose your own method of working; your fellow workers; the recognition you get for good work; your immediate boss; the amount of responsibility you are given; your rate of pay; your opportunity to use your abilities; relations between managers and workers; your workload; your chance of promotion; the equipment you use; the way your firm is managed; your hours of work; the amount of variety in your job; and your job security. An average satisfaction score may be calculated across all the items, responses to each item being scored from 1 to 5, for instance (see the preceding paragraph). Alternatively, separate values can be computed for “intrinsic satisfaction” items (those dealing with the content of the work itself) and “extrinsic satisfaction” items (those referring to the context of the work, such as colleagues and working conditions).

Self-report scales which measure axes two and three have often covered only one end of the possible distribution. For example, some scales of job-related anxiety ask about a worker’s feelings of tension and worry when on the job (2a), but do not in addition test for more positive forms of affect on this axis (2b). Based on studies in several settings (Watson, Clark and Tellegen 1988; Warr 1990), a possible approach is as follows.

Axes 2 and 3 may be examined by putting this question to workers: “Thinking of the past few weeks, how much of the time has your job made you feel each of the following?”, with response options of never, occasionally, some of the time, much of the time, most of the time, and all the time (scored from 1 to 6 respectively). Anxiety-to-comfort ranges across these states: tense, anxious, worried, calm, comfortable and relaxed. Depression-to-enthusiasm covers these states: depressed, gloomy, miserable, motivated, enthusiastic and optimistic. In each case, the first three items should be reverse-scored, so that a high score always reflects high well-being, and the items should be mixed randomly in the questionnaire. A total or average score can be computed for each axis.

More generally, it should be noted that affective well-being is not determined solely by a person’s current environment. Although job characteristics can have a substantial effect, well-being is also a function of some aspects of personality; people differ in their baseline well-being as well as in their reactions to particular job characteristics.

Relevant personality differences are usually described in terms of individuals’ continuing affective dispositions. The personality trait of positive affectivity (corresponding to the upper right-quadrant) is characterized by generally optimistic views of the future, emotions which tend to be positive and behaviours which are relatively extroverted. On the other hand, negative affectivity (corresponding to the upper left-hand quadrant) is a disposition to experience negative emotional states. Individuals with high negative affectivity tend in many situations to feel nervous, anxious or upset; this trait is sometimes measured by means of personality scales of neuroticism. Positive and negative affectivities are regarded as traits, that is, they are relatively constant from one situation to another, whereas a person’s well-being is viewed as an emotional state which varies in response to current activities and environmental influences.

Measures of well-being necessarily identify both the trait (the affective disposition) and the state (current affect). This fact should be borne in mind in examining people’s well-being score on an individual basis, but it is not a substantial problem in studies of the average findings for a group of employees. In longitudinal investigations of group scores, observed changes in well-being can be attributed directly to changes in the environment, since every person’s baseline well-being is held constant across the occasions of measurement; and in cross-sectional group studies an average affective disposition is recorded as a background influence in all cases.

Note also that affective well-being may be viewed at two levels. The more focused perspective relates to a specific domain, such as an occupational setting: this may be a question of “job-related” well-being (as discussed here) and is measured through scales which directly concern feelings when a person is at work. However, more wide-ranging, “context-free” or “general,” well-being is sometimes of interest, and measurement of that wider construct requires a less specific focus. The same three axes should be examined in both cases, and more general scales are available for life satisfaction or general distress (axis 1), context-free anxiety (axis 2) and context-free depression (axis 3).