Metalworking involves casting, welding, brazing, forging, soldering, fabrication and surface treatment of metal. Metalworking is becoming even more common as artists in developing countries are also starting to use metal as a basic sculptural material. While many art foundries are commercially run, art foundries are also often part of college art programmes.

Hazards and Precautions

Casting and foundry

Artists either send work out to commercial foundries, or can cast metal in their own studios. The lost wax process is often used for casting small pieces. Common metals and alloys used are bronze, aluminium, brass, pewter, iron and stainless steel. Gold, silver and sometimes platinum are used for casting small pieces, particularly for jewellery.

The lost wax process involves several steps:

- making the positive form

- making the investment mould

- burning out of the wax

- melting the metal

- slagging

- pouring the molten metal into the mould

- removing the mould

The positive form can be made directly in wax; it can also be made in plaster or other materials, a negative mould made in rubber and then the final positive form cast in wax. Heating the wax can result in fire hazards and in decomposition of the wax from overheating.

The mould is commonly made by applying an investment containing the cristobalite form of silica, creating the risk of silicosis. A 50/50 mixture of plaster and 30-mesh sand is a safer substitute. Moulds can also be made using sand and oil, formaldehyde resins and other resins as binders. Many of these resins are toxic by skin contact and inhalation, requiring skin protection and ventilation.

The wax form is burnt out in a kiln. This requires local exhaust ventilation to remove the acrolein and other irritating wax decomposition products.

Melting the metal is usually done in a gas-fired crucible furnace. A canopy hood exhausted to the outside is needed to remove carbon monoxide and metal fumes, including zinc, copper, lead, aluminium and so on.

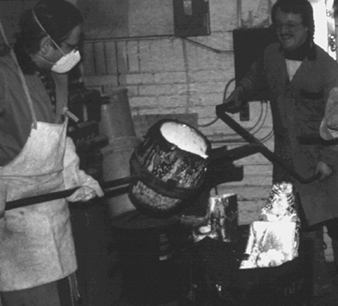

The crucible containing the molten metal is then removed from the furnace, the slag on the surface removed and the molten metal poured into the moulds (figure 1). For weights under 80 pounds of metal, manual lifting is normal; for greater weights, lifting equipment is needed. Ventilation is needed for the slagging and pouring operations to remove metal fumes. Resin sand moulds can also produce hazardous decomposition products from the heat. Face shields protecting against infrared radiation and heat, and personal protective clothing resistant to heat and molten metal splashes are essential. Cement floors must be protected against molten metal splashes by a layer of sand.

Figure 1. Pouring molten metal in art foundry.

Ted Rickard

Breaking away the mould can result in exposure to silica. Local exhaust ventilation or respiratory protection is needed. A variation of the lost wax process called the foam vaporization process involves using polystyrene or polyurethane foam instead of wax, and vaporizing the foam during pouring of the molten metal. This can release hazardous decomposition products, including hydrogen cyanide from polyurethane foam. Artists often use scrap metal from a variety of sources. This practice can be dangerous due to possible presence of lead- and mercury-containing paints, and to the possible presence of metals like cadmium, chromium, nickel and so on in the metals.

Fabrication

Metal can be cut, drilled and filed using saws, drills, snips and metal files. The metal filings can irritate the skin and eyes. Electric tools can cause electric shock. Improper handling of these tools can result in accidents. Goggles are needed to protect the eyes from flying chips and filings. All electrical equipment should be properly grounded. All tools should be carefully handled and stored. Metal to be fabricated should be securely clamped to prevent accidents.

Forging

Cold forging utilizes hammers, mallets, anvils and similar tools to change the shape of metal. Hot forging involves additionally heating the metal. Forging can create great amounts of noise, which can cause hearing loss. Small metal splinters may damage the skin or eyes if precautions are not taken. Burns are also a hazard with hot forging. Precautions include good tools, eye protection, routine clean-up, proper work clothing, isolation of the forging area and wearing ear plugs or ear muffs.

Hot forging involves the burning of gas, coke or other fuels. A canopy hood for ventilation is needed to exhaust carbon monoxide and possible polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions, and to reduce heat build-up. Infrared goggles should be worn for protection against infrared radiation.

Surface treatment

Mechanical treatment (chasing, repousse) is done with hammers, engraving with sharp tools, etching with acids, photoetching with acids and photochemicals, electroplating (plating a metallic film onto another metal) and electroforming (plating a metallic film onto a non-metallic object) with acids and cyanide solutions and metal colouring with many chemicals.

Electroplating and electroforming often use cyanide salts, ingestion of which can be fatal. Accidental mixing of acids and the cyanide solution will produce hydrogen cyanide gas. This is hazardous through both skin absorption and inhalation—death can occur within minutes. Disposal and waste management of spent cyanide solutions is strictly regulated in many countries. Electroplating with cyanide solutions should be done in a commercial plant; otherwise use substitutes that do not contain cyanide salts or other cyanide-containing materials.

Acids are corrosive, and skin and eye protection is needed. Local exhaust ventilation with acid-resistant ductwork is recommended.

Anodizing metals such as titanium and tantalum involves oxidizing these at the anode of an electrolytic bath to colour them. Hydrofluoric acid can be used for precleaning. Avoid using hydrofluoric acid or use gloves, goggles and a protective apron.

Patinas used to colour metals can be applied cold or hot. Lead and arsenic compounds are very toxic in any form, and others can give off toxic gases when heated. Potassium ferricyanide solutions will give off hydrogen cyanide gas when heated, arsenic acid solutions give off arsine gas and sulphide solutions give off hydrogen sulphide gas. Very good ventilation is needed for metal colouring (figure 2). Arsenic compounds and heating of potassium ferrocyanide solutions should be avoided.

Figure 2. Applying a patina to metal with slot exhaust hood.

Ken Jones

Finishing processes

Cleaning, grinding, filing, sandblasting and polishing are some final treatments for metal. Cleaning involves the use of acids (pickling). This involves the hazards of handling acids and of the gases produced during the pickling process (such as nitrogen dioxide from nitric acid). Grinding can result in the production of fine metal dusts (which can be inhaled) and heavy flying particles (which are eye hazards).

Sandblasting (abrasive blasting) is very hazardous, particularly with actual sand. Inhalation of fine silica dust from sandblasting can cause silicosis in a short time. Sand should be replaced with glass beads, aluminium oxide or silicon carbide. Foundry slags should be used only if chemical analysis shows no silica or dangerous metals such as arsenic or nickel. Good ventilation or respiratory protection is needed.

Polishing with abrasives such as rouge (iron oxide) or tripoli can be hazardous since rouge can be contaminated with large amounts of free silica, and tripoli contains silica. Good ventilation of the polishing wheel is needed.

Welding

Physical hazards in welding include the danger of fire, electric shock from arc-welding equipment, burns caused by molten metal sparks, and injuries caused by excessive exposure to infrared and ultraviolet radiation. Welding sparks can travel 40 feet.

Infrared radiation can cause burns and eye damage. Ultraviolet radiation can cause sunburn; repeated exposure may lead to skin cancer. Electric arc welders in particular are subject to pink eye (conjunctivitis), and some have cornea damage from UV exposure. Skin protection and welding goggles with UV- and IR-protective lenses are needed.

Oxyacetylene torches produce carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and unburned acetylene, which is a mild intoxicant. Commercial acetylene contains small amounts of other toxic gases and impurities.

Compressed gas cylinders can be both explosive and fire hazards. All cylinders, connections and hoses must be carefully maintained and inspected. All gas cylinders must be stored in a location which is dry, well ventilated and secure from unauthorized persons. Fuel cylinders must be stored separately from oxygen cylinders.

Arc welding produces enough energy to convert the air’s nitrogen and oxygen to nitrogen oxides and ozone, which are lung irritants. When arc welding is done within 20 feet of chlorinated degreasing solvents, phosgene gas can be produced by the UV radiation.

Metal fumes are generated by the vaporization of metals, metal alloys and the electrodes used in arc welding. Fluoride fluxes produce fluoride fumes.

Ventilation is needed for all welding processes. While dilution ventilation may be adequate for mild steel welding, local exhaust ventilation is necessary for most welding operations. Moveable flanged hoods, or lateral slot hoods should be used. Respiratory protection is needed if ventilation is not available.

Many metal dusts and fumes can cause skin irritation and sensitization. These include brass dust (copper, zinc, lead and tin), cadmium, nickel, titanium and chromium.

In addition, there are problems with welding materials that may be coated with various substances (e.g., lead or mercury paint).