Aquatic Animals

D. Zannini*

* Adapted from 3rd edition, Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety.

Aquatic animals dangerous to humans are to be found among practically all of the divisions (phyla). Workers may come into contact with these animals in the course of various activities including surface and underwater fishing, the installation and handling of equipment in connection with the exploitation of petroleum under the sea, underwater construction, and scientific research, and thus be exposed to health risks. Most of the dangerous species inhabit warm or temperate waters.

Characteristics and Behaviour

Porifera. The common sponge belongs to this phylum. Fishermen who handle sponges, including helmet and scuba divers, and other underwater swimmers, may contract contact dermatitis with skin irritation, vesicles or blisters. The “sponge diver’s sickness” of the Mediterranean region is caused by the tentacles of a small coelenterate (Sagartia rosea) that is a parasite of the sponge. A form of dermatitis known as “red moss” is found among North American oyster fishers resulting from contact with a scarlet sponge found on the shell of the oysters. Cases of type 4 allergy have been reported. The poison secreted by the sponge Suberitus ficus contains histamine and antibiotic substances.

Coelenterata. These are represented by many families of the class known as Hydrozoa, which includes the Millepora or coral (stinging coral, fire coral), the Physalia (Physalia physalis, sea wasp, Portuguese man-of-war), the Scyphozoa (jellyfish) and the Actiniaria (stinging anemone), all of which are found in all parts of the ocean. Common to all these animals is their ability to produce an urticaria by the injection of a strong poison that is retained in a special cell (the cnidoblast) containing a hollow thread, which explodes outwards when the tentacle is touched, and penetrates the person’s skin. The various substances contained in this structure are responsible for such symptoms as severe itching, congestion of the liver, pain, and depression of the central nervous system; these substances have been identified as thalassium, congestine, equinotoxin (which contains 5-hydroxytryptamine and tetramine) and hypnotoxin, respectively. Effects on the individual depend upon the extent of the contact made with the tentacles and hence on the number of microscopic punctures, which may amount to many thousands, up to the point where they may cause the death of the victim within a few minutes. In view of the fact that these animals are dispersed so widely throughout the world, many incidents of this nature occur but the number of fatalities is relatively small. Effects on the skin are characterized by intense itching and the formation of papules having a bright red, mottled appearance, developing into pustules and ulceration. Intense pain similar to electric shock may be felt. Other symptoms include difficulty in breathing, generalized anxiety and cardiac upset, collapse, nausea and vomiting, loss of consciousness, and primary shock.

Echinoderma. This group includes the starfishes and sea urchins, both of which possess poisonous organs (pedicellariae), but are not dangerous to humans. The spine of the sea urchin can penetrate the skin, leaving a fragment deeply imbedded; this can give rise to a secondary infection followed by pustules and persistent granuloma, which can be very troublesome if the wounds are close to tendons or ligaments. Among the sea urchins, only the Acanthaster planci seems to have a poisonous spine, which can give rise to general disturbances such as vomiting, paralysis and numbness.

Mollusca. Among the animals belonging to this phylum are the cone shells, and these can be dangerous. They live on a sandy sea-bottom and appear to have a poisonous structure consisting of a radula with needle-like teeth, which can strike at the victim if the shell is handled incautiously with the bare hand. The poison acts on the neuromuscular and central nervous systems. Penetration of the skin by the point of a tooth is followed by temporary ischaemia, cyanosis, numbness, pain, and paraesthesia as the poison spreads gradually through the body. Subsequent effects include paralysis of the voluntary muscles, lack of coordination, double vision and general confusion. Death can follow as a result of respiratory paralysis and circulatory collapse. Some 30 cases have been reported, of which 8 were fatal.

Platyhelminthes. These include the Eirythoe complanata and the Hermodice caruncolata, known as “bristle worms”. They are covered with numerous bristle-like appendages, or setae, containing a poison (nereistotoxin) with a neurotoxic and local irritant effect.

Polyzoa (Bryozoa). These are made up of a group of animals which form plant-like colonies resembling gelatinous moss, which frequently encrust rocks or shells. One variety, known as Alcyonidium, can cause an urticarious dermatitis on the arms and face of fishermen who have to clean this moss off their nets. It can also give rise to an allergic eczema.

Selachiis (Chondrichthyes). Animals belonging to this phylum include the sharks and sting-rays. The sharks live in fairly shallow water, where they search for prey and may attack people. Many varieties have one or two large, poisonous spines in front of the dorsal fin, which contain a weak poison that has not been identified; these can cause a wound giving rise to immediate and intense pain with reddening of the flesh, swelling and oedema. A far greater danger from these animals is their bite, which, because of several rows of sharp pointed teeth, causes severe laceration and tearing of the flesh leading to immediate shock, acute anaemia and drowning of the victim. The danger that sharks represent is a much-discussed subject, each variety seeming to be particularly aggressive. There seems no doubt that their behaviour is unpredictable, although it is said that they are attracted by movement and by the light colour of a swimmer, as well as by blood and by vibrations resulting from a fish or other prey that has just been caught. Sting-rays have large, flat bodies with a long tail having one or more strong spines or saws, which can be poisonous. The poison contains serotonine, 5-nucleotidase and phosphodiesterase, and can cause generalized vasoconstriction and cardio-respiratory arrest. Sting-rays live in the sandy regions of coastal waters, where they are well hidden, making it easy for bathers to step on one without seeing it. The ray reacts by bringing over its tail with the projecting spine, impaling the spike keep into the flesh of the victim. This may cause piercing wounds in a limb or even penetration of an internal organ such as the peritoneum, lung, heart or liver, particularly in the case of children. The wound can also give rise to great pain, swelling, lymphatic oedema and various general symptoms such as primary shock and cardio-circulatory collapse. Injury to an internal organ may lead to death in a few hours. Sting-ray incidents are among the most frequent, there being some 750 every year in the United States alone. They can also be dangerous for fishermen, who should immediately cut off the tail as soon as the fish is brought aboard. Various species of rays such as the torpedo and the narcine possess electric organs on their back, which, when stimulated by touch alone, can produce electric shocks ranging from 8 up to 220 volts; this may be enough to stun and temporarily disable the victim, but recovery is usually without complications.

Osteichthyes. Many fishes of this phylum have dorsal, pectoral, caudal and anal spines which are connected with a poison system and whose primary purpose is defence. If the fish is disturbed or stepped upon or handled by a fisherman, it will erect the spines, which can pierce the skin and inject the poison. Not infrequently they will attack a diver seeking fish, or if they are disturbed by accidental contact. Numerous incidents of this kind are reported because of the widespread distribution of fish of this phylum, which includes the catfish, which are also found in fresh water (South America, West Africa and the Great Lakes), the scorpion fish (Scorpaenidae), the weever fish (Trachinus), the toadfish, the surgeon fish and others. Wounds from these fishes are generally painful, particularly in the case of the catfish and the weever fish, causing reddening or pallor, swelling, cyanosis, numbness, lymphatic oedema and haemorrhagic suffusion in the surrounding flesh. There is a possibility of gangrene or phlegmonous infection and peripheral neuritis on the same side as the wound. Other symptoms include faintness, nausea, collapse, primary shock, asthma and loss of consciousness. They all represent a serious danger for underwater workers. A neurotoxic and haemotoxic poison has been identified in the catfish, and in the case of the weever fish a number of substances have been isolated such as 5-hydroxytryptamine, histamine and catecholamine. Some catfishes and stargazers that live in fresh water, as well as the electric eel (Electrophorus), have electric organs (see under Selachii above).

Hydrophiidae. This group (sea snakes) is to be found mostly in the seas around Indonesia and Malaysia; some 50 species have been reported, including Pelaniis platurus, Enhydrina schistosa and Hydrus platurus. The venom of these snakes is very similar to that of the cobra, but is 20 to 50 times as poisonous; it is made up of a basic protein of low molecular weight (erubotoxin) which affects the neuromuscular junction blocking the acetylcholine and provoking myolysis. Fortunately sea snakes are generally docile and bite only when stepped on, squeezed or dealt a hard blow; furthermore, they inject little or no venom from their teeth. Fishermen are among those most exposed to this hazard and account for 90% of all reported incidents, which result either from stepping on the snake on the sea bottom or from encountering them among their catch. Snakes are probably responsible for thousands of the occupational accidents attributed to aquatic animals, but few of these are serious, while only a small percentage of the serious accidents turn out to be fatal. Symptoms are mostly slight and not painful. Effects are usually felt within two hours, starting with muscular pain, difficulty with neck movement, lack of dexterity, and trismus, and sometimes including nausea and vomiting. Within a few hours myoglobinuria (the presence of complex proteins in urine) will be seen. Death can ensue from paralysis of the respiratory muscles, from renal insufficiency due to tubular necrosis, or from cardiac arrest due to hyperkalaemia.

Prevention

Every effort should be made to avoid all contact with the spines of these animals when they are being handled, unless strong gloves are worn, and the greatest care should be taken when wading or walking on a sandy sea bottom. The wet suit worn by skin divers offers protection against the jellyfish and the various Coelenterata as well as against snakebite. The more dangerous and aggressive animals should not be molested, and zones where there are jellyfish should be avoided, as they are difficult to see. If a sea snake is caught on a line, the line should be cut and the snake allowed to go. If sharks are encountered, there are a number of principles that should be observed. People should keep their feet and legs out of the water, and the boat should be gently brought to shore and kept still; a swimmer should not stay in the water with a dying fish or with one that is bleeding; a shark’s attention should not be attracted by the use of bright colours, jewellery, or by making a noise or explosion, by showing a bright light, or by waving the hands towards it. A diver should never dive alone.

Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic cancer (ICD-9 157; ICD-10 C25), a highly fatal malignancy, ranks amongst the 15 most common cancers globally but belongs to the ten most common cancers in the populations of developed countries, accounting for 2 to 3% of all new cases of cancer (IARC 1993). An estimated 185,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer occurred globally in 1985 (Parkin, Pisani and Ferlay 1993). The incidence rates of pancreatic cancer have been increasing in developed countries. In Europe, the increase has levelled off, except in the UK and some Nordic countries (Fernandez et al. 1994). The incidence and mortality rates rise steeply with advancing age between 30 and 70 years. The age-adjusted male/female ratio of new cases of pancreatic cancer is 1.6/1 in developed countries but only 1.1/1 in developing countries.

High annual incidence rates of pancreatic cancer (up to 30/100,000 for men; 20/100,000 for women) in the period 1960-85, have been recorded for New Zealand Maoris, Hawaiians, and in Black populations in the US. Regionally, the highest age-adjusted rates in 1985 (over 7/100,000 for men and 4/100,000 in women) were reported for both genders in Japan, North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Northern, Western and Eastern Europe. The lowest rates (up to 2/100,000 for both men and women) were reported in the regions of West and Middle Africa, South-eastern Asia, Melanesia, and in temperate South America (IARC 1992; Parkin, Pisani and Ferlay 1993).

Comparisons between populations in time and space are subject to several cautions and interpretation difficulties because of variations in diagnostic conventions and technologies (Mack 1982).

The vast majority of pancreatic cancers occur in the exocrine pancreas. The major symptoms are abdominal and back pain and weight loss. Further symptoms include anorexia, diabetes and obstructive jaundice. Symptomatic patients are subjected to procedures such as a series of blood and urine tests, ultrasound, computerized tomography, cytological examination and pancreatoscopy. Most patients have metastases at diagnosis, which makes their prognosis bleak.

Only 15% of patients with pancreatic cancer are operable. Local recurrence and distant metastases occur frequently after surgery. Irradiation therapy or chemotherapy do not bring about significant improvements in survival except when combined with surgery on localized carcinomas. Palliative procedures provide little benefit. Despite some diagnostic improvements, survival remains poor. During the period 1983-85, the five-year average survival in 11 European populations was 3% for men and 4% for women (IARC 1995). Very early detection and diagnosis or identification of high-risk individuals may improve the success of surgery. The efficacy of screening for pancreatic cancer has not been determined.

Mortality and incidence of pancreatic cancer do not reveal a consistent global pattern across socio-economic categories.

The dismal picture offered by diagnostic problems and treatment inefficacy is completed by the fact that the causes of pancreatic cancer are largely unknown, which effectively hampers the prevention of this fatal disease. The unique established cause of pancreatic cancer is tobacco smoking, which explains about 20-50% of the cases, depending on the smoking patterns of the population. It has been estimated that elimination of tobacco smoking would decrease the incidence of pancreatic cancer by about 30% worldwide (IARC 1990). Alcohol consumption and coffee drinking have been suspected as increasing the risk of pancreatic cancer. On closer scrutiny of the epidemiological data, however, coffee consumption appears unlikely to be causally connected to pancreatic cancer. For alcoholic beverages, the only causal link with pancreatic cancer is probably pancreatitis, a condition associated with heavy alcohol consumption. Pancreatitis is a rare but potent risk factor of pancreatic cancer. It is possible that some as yet unidentified dietary factors might account for a part of the aetiology of pancreatic cancer.

Workplace exposures may be causally associated with pancreatic cancer. Results of several epidemiological studies that have linked industries and jobs with an excess of pancreatic cancer are heterogeneous and inconsistent, and exposures shared by alleged high-risk jobs are hard to identify. The population aetiologic fraction for pancreatic cancer from occupational exposures in Montreal, Canada, has been estimated to lie between 0% (based on recognized carcinogens) and 26% (based on a multi-site case-control study in the Montreal area, Canada) (Siemiatycki et al. 1991).

No single occupational exposure has been confirmed to increase the risk of pancreatic cancer. Most of the occupational chemical agents that have been associated with an excess risk in epidemiological studies emerged in one study only, suggesting that many of the associations may be artefacts from confounding or chance. If no additional information, e.g., from animal bio-assays, is available, the distinction between spurious and causal associations presents formidable difficulties, given the general uncertainty about the causative agents involved in the development of pancreatic cancer. Agents associated with increased risk include aluminium, aromatic amines, asbestos, ashes and soot, brass dust, chromates, combustion products of coal, natural gas and wood, copper fumes, cotton dust, cleaning agents, grain dust, hydrogen fluoride, inorganic insulation dust, ionizing radiation, lead fumes, nickel compounds, nitrogen oxides, organic solvents and paint thinners, paints, pesticides, phenol-formaldehyde, plastic dust, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, rayon fibres, stainless steel dust, sulphuric acid, synthetic adhesives, tin compounds and fumes, waxes and polishes, and zinc fumes (Kauppinen et al. 1995). Among these agents, only aluminium, ionizing radiation and unspecified pesticides have been associated with excess risk in more than one study.

Liver Cancer

The predominant type of malignant tumour of the liver (ICD-9 155) is hepatocellular carcinoma (hepatoma; HCC), i.e., a malignant tumour of the liver cells. Cholangiocarcinomas are tumours of the intrahepatic bile ducts. They represent some 10% of liver cancers in the US but may account for up to 60% elsewhere, such as in north-eastern Thai populations (IARC 1990). Angiosarcomas of the liver are very rare and very aggressive tumours, occurring mostly in men. Hepatoblastomas, a rare embryonal cancer, occur in early life, and have little geographic or ethnic variation.

The prognosis for HCC depends on the size of the tumour and on the extent of cirrhosis, metastases, lymph node involvement, vascular invasion and presence/absence of a capsule. They tend to relapse after resection. Small HCCs are resectable, with a five-year survival of 40-70%. Liver transplantation results in about 20% survival after two years for patients with advanced HCC. For patients with less advanced HCC, the prognosis after transplantation is better. For hepatoblastomas, complete resection is possible in 50-70% of the children. Cure rates after resection range from 30-70%. Chemotherapy can be used both pre- and postoperatively. Liver transplantation may be indicated for unresectable hepatoblastomas.

Cholangiocarcinomas are multifocal in more than 40% of the patients at the time of diagnosis. Lymph node metastases occur in 30-50% of these cases. The response rates to chemotherapy vary widely, but usually are less than 20% successful. Surgical resection is possible in only a few patients. Radiation therapy has been used as the primary treatment or adjuvant therapy, and may improve survival in patients who have not undergone a complete resection. Five-year survival rates are less than 20%. Angiosarcoma patients usually present distant metastases. Resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy and liver transplantation are, in most cases, unsuccessful. Most patients die within six months of diagnosis (Lotze, Flickinger and Carr 1993).

An estimated 315,000 new cases of liver cancer occurred globally in 1985, with a clear absolute and relative preponderance in populations of developing countries, except in Latin America (IARC 1994a; Parkin, Pisani and Ferlay 1993). The average annual incidence of liver cancer shows considerable variation across cancer registries worldwide. During the 1980s, average annual incidence ranged from 0.8 in men and 0.2 in women in Maastricht, The Netherlands, to 90.0 in men and 38.3 in women in Khon Kaen, Thailand, per 100,000 of population, standardized to the standard world population. China, Japan, East Asia, and Africa represented high rates, while Latin and North American, European, and Oceanian rates were lower, except for New Zealand Maoris (IARC 1992). The geographic distribution of liver cancer is correlated with the distribution of the prevalence of chronic carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen and also with the distribution of local levels of aflatoxin contamination of foodstuffs (IARC 1990). Male-to-female ratios in incidence are usually between 1 and 3, but may be higher in high-risk populations.

Statistics on the mortality and incidence of liver cancer by social class indicate a tendency of excess risk to concentrate in the lower socio-economic strata, but this gradient is not observed in all populations.

The established risk factors for primary liver cancer in humans include aflatoxin-contaminated food, chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (IARC 1994b), chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (IARC 1994b), and heavy consumption of alcoholic beverages (IARC 1988). HBV is responsible for an estimated 50-90% of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in high-risk populations, and for 1-10% in low-risk populations. Oral contraceptives are a further suspected factor. The evidence implicating tobacco smoking in the aetiology of liver cancer is insufficient (Higginson, Muir and Munoz 1992).

The substantial geographical variation in the incidence of liver cancer suggests that a high proportion of liver cancers might be preventable. The preventive measures include HBV vaccination (estimated potential theoretical reduction in incidence is roughly 70% in endemic areas), reduction of contamination of food by mycotoxins (40% reduction in endemic areas), improved methods of harvesting, dry storing of crops, and reduction of consumption of alcoholic beverages (15% reduction in Western countries; IARC 1990).

Liver cancer excesses have been reported in a number of occupational and industrial groups in different countries. Some of the positive associations are readily explained by workplace exposures such as the increased risk of liver angiosarcoma in vinyl chloride workers (see below). For other high-risk jobs, such as metal work, construction painting, and animal feed processing, the connection with workplace exposures is not firmly established and is not found in all studies, but could well exist. For others, such as service workers, police officers, guards, and governmental workers, direct workplace carcinogens may not explain the excess. Cancer data for farmers do not provide many clues for occupational aetiologies in liver cancer. In a review of 13 studies involving 510 cases or deaths of liver cancer among farmers (Blair et al. 1992), a slight deficit (aggregated risk ratio 0.89; 95% confidence interval 0.81-0.97) was observed.

Some of the clues provided by industry- or job-specific epidemiological studies do suggest that occupational exposures may have a role in the induction of liver cancer. Minimization of certain occupational exposures therefore would be instrumental in the prevention of liver cancer in occupationally exposed populations. As a classical example, occupational exposure to vinyl chloride has been shown to cause angiosarcoma of the liver, a rare form of liver cancer (IARC 1987). As a result, vinyl chloride exposure has been regulated in a large number of countries. There is increasing evidence that chlorinated hydrocarbon solvents may cause liver cancer. Aflatoxins, chlorophenols, ethylene glycol, tin compounds, insecticides and some other agents have been associated with the risk of liver cancer in epidemiological studies. Numerous chemical agents occurring in occupational settings have caused liver cancer in animals and may therefore be suspected of being liver carcinogens in humans. Such agents include aflatoxins, aromatic amines, azo dyes, benzidine-based dyes, 1,2-dibromoethane, butadiene, carbon tetrachloride, chlorobenzenes, chloroform, chlorophenols, diethylhexyl phthalate, 1,2-dichloroethane, hydrazine, methylene chloride, N-nitrosoamines, a number of organochlorine pesticides, perchloroethylene, polychlorinated biphenyls and toxaphene.

Peptic Ulcer

Gastric and duodenal ulcers—collectively called “peptic ulcers”—are a sharply circumscribed loss of tissue, involving the mucosa, submucosa and muscular layer, occurring in areas of the stomach or duodenum exposed to acid-pepsin gastric juice. Peptic ulcer is a common cause of recurring or persistent upper abdominal distress, especially in young men. Duodenal ulcer comprises about 80% of all peptic ulcers, and is commoner in men than in women; in gastric ulcer the gender ratio is about one. It is important to distinguish between gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer because of differences in diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. The causes of peptic ulcer have not been completely determined; many factors are believed to be involved, and in particular nervous tension, the ingestion of certain drugs (such as salicylates and corticoids) and hormonal factors may play roles.

Persons at Risk

Although peptic ulcer cannot be regarded as a specific occupational disease, it has a higher-than-average incidence among professional people and those working under stress. Stress, either physical or emotional, is believed to be an important factor in the aetiology of peptic ulcer; prolonged emotional stress in various occupations may increase the secretion of hydrochloric acid and the susceptibility of the gastroduodenal mucosa to injury.

The results of many investigations of the relationship between peptic ulcer and occupation clearly reveal substantial variations in the incidence of ulcers in different occupations. Numerous studies point to the likelihood of transport workers, such as drivers, motor mechanics, tramcar conductors and railway employees, contracting ulcers. Thus, in one survey covering over 3,000 railway workers, peptic ulcers were found to be more frequent in train crew, signal operators and inspectors than in maintenance and administrative staff; shift work, hazards and responsibility being noted as contributing factors. In another large-scale survey, however, transport workers evidenced “normal” ulcer rates, the incidence being highest in doctors and a group of unskilled workers. Fishers and sea pilots also tend to suffer from peptic ulcer, predominantly of the gastric type. In a study of coal miners, the incidence of peptic ulcers was found to be proportional to the arduousness of the work, being highest in miners employed at the coal face. Reports of cases of peptic ulcer in welders and in workers in a magnesium refining plant suggest that metal fumes are capable of inducing this condition (although here the cause would appear to be not stress, but a toxic mechanism). Elevated incidences have also been found among overseers and business executives, i.e., generally in persons holding responsible posts in industry or trade; it is noteworthy that duodenal ulcers account almost exclusively for the high incidence in these groups, the incidence of gastric ulcer being average.

On the other hand, low incidences of peptic ulcer have been found among agricultural workers, and apparently prevail among sedentary workers, students and draftsmen.

Thus, while the evidence regarding the occupational incidence of peptic ulcer appears to be contradictory to a degree, there is agreement at least on one point, namely that the higher the stresses of the occupation, the higher the ulcer rate. This general relationship can also be observed in the developing countries, where, during the process of industrialization and modernization, many workers are coming increasingly under the influence of stress and strain, caused by such factors as congested traffic and difficult commuting conditions, introduction of complex machinery, systems and technologies, heavier workloads and longer working hours, all of which are found to be conducive to the development of peptic ulcer.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of peptic ulcer depends upon obtaining a history of characteristic ulcer distress, with relief of distress on ingestion of food or alkali, or other manifestations such as gastro-intestinal bleeding; the most useful diagnostic technique is a thorough x-ray study of the upper gastro-intestinal tract.

Attempts to gather data on the prevalence of this condition have been seriously hampered by the fact that peptic ulcer is not a reportable disease, that workers with peptic ulcer frequently put off consulting a physician about their symptoms, and that when they do so, the criteria for diagnosis are not uniform. The detection of peptic ulcer in workers is, therefore, not simple. Some excellent researchers, indeed, have had to rely on attempts to gather data from necropsy records, questionnaires to physicians, and insurance company statistics.

Preventive Measures

From the viewpoint of occupational medicine, the prevention of peptic ulcer—seen as a psychosomatic ailment with occupational connotations—must be based primarily on the alleviation, wherever possible, of overstress and nervous tension due to directly or indirectly work-related factors. Within the broad framework of this general principle, there is room for a wide variety of measures, including, for example, action on the collective plane towards a reduction of working hours, the introduction or improvement of facilities for rest and relaxation, improvements in financial conditions and social security, and (hand in hand with local authorities) steps to improve commuting conditions and make suitable housing available within a reasonable distance of workplaces—not to mention direct action to pinpoint and eliminate particular stress-generating situations in the working environment.

At the personal level, successful prevention depends equally on proper medical guidance and on intelligent cooperation by the worker, who should have an opportunity of seeking advice on work-connected and other personal problems.

The liability of individuals to contract peptic ulcers is heightened by various occupational factors and personal attributes. If these factors can be recognized and understood, and above all, if the reasons for the apparent correlation between certain occupations and high ulcer rates can be clearly demonstrated, the chances of successful prevention, and treatment of relapses, will be greatly enhanced. A possible Helicobacter infection should also be eradicated. In the meantime, as a general precaution, the implications of a past history of peptic ulcer should be borne in mind by persons conducting pre-employment or periodic examinations, and efforts should be made not to place—or to leave—the workers concerned in jobs or situations where they will be exposed to severe stresses, particularly of a nervous or psychological nature.

Liver

The liver acts as a vast chemical factory with diverse vital functions. It plays an essential role in the metabolism of protein, carbohydrate and fat, and is concerned with the absorption and storage of vitamins and with the synthesis of prothrombin and other factors concerned with blood clotting. The liver is responsible for the inactivation of hormones and the detoxification of many drugs and exogenous toxic chemical substances. It also excretes the breakdown products of haemoglobin, which are the principal constituents of the bile. These widely varying functions are performed by parenchymal cells of uniform structure which contain many complex enzyme systems.

Pathophysiology

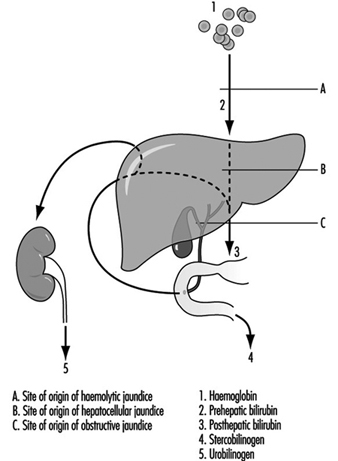

An important feature of liver disease is a rise in the level of bilirubin in the blood; if of sufficient magnitude, this stains the tissues to give rise to jaundice. The mechanism of this process is shown in figure 1. Haemoglobin released from worn out red blood cells is broken down to haem and then, by removal of iron, to bilirubin before it reaches the liver (prehepatic bilirubin). In its passage through the liver cell, bilirubin is conjugated by enzymatic activity into water-soluble glucuronides (posthepatic bilirubin) and then secreted as bile into the intestine. The bulk of this pigment is eventually excreted in the stool, but some is reabsorbed through the intestinal mucosa and secreted a second time by the liver cell into the bile (enterohepatic circulation). However, a small proportion of this reabsorbed pigment is finally excreted in the urine as urobilinogen. With normal liver function there is no bilirubin in the urine, as prehepatic bilirubin is protein bound, but a small amount of urobilinogen is present.

Figure 1. The excretion of bilirubinthrough thte liver, showing the enterohepatic circulation.

Obstruction to the biliary system can occur in the bile ducts, or at cellular level by swelling of the hepatic cells due to injury, with resulting obstruction to the fine bile canaliculi. Posthepatic bilirubin then accumulates in the bloodstream to produce jaundice, and overflows into the urine. The secretion of bile pigment into the intestine is hindered, and urobilinogen is no longer excreted in the urine. The stools are therefore pale due to lack of pigment, the urine dark with bile, and the serum conjugated bilirubin raised above its normal value to give rise to obstructive jaundice.

Damage to the liver cell, which may follow injection of or exposure to toxic agents, also gives rise to an accumulation of posthepatic, conjugated bilirubin (hepatocellular jaundice). This may be sufficiently severe and prolonged to give rise to a transient obstructive picture, with bilirubin but no urobilinogen in the urine. However, in the early stages of hepatocellular damage, without obstruction present, the liver is unable to re-excrete reabsorbed bilirubin, and an excessive amount of urobilinogen is excreted in the urine.

When blood cells are broken down at an excessive rate, as in the haemolytic anaemias, the liver becomes overloaded and the unconjugated prehepatic bilirubin is raised. This again gives rise to jaundice. However, prehepatic bilirubin cannot be excreted in the urine. Excessive amounts of bilirubin are secreted into the intestine, rendering the faeces dark. More is reabsorbed via the enterohepatic circulation and an increased amount of urobilinogen excreted in the urine (haemolytic jaundice).

Diagnosis

Liver function tests are used to confirm suspected liver disease, to estimate progress and to assist in the differential diagnosis of jaundice. A series of tests is usually applied to screen the various functions of the liver, those of established value being:

- Examination of the urine for the presence of bilirubin and urobilinogen: The former is indicative of hepatocellular damage or of biliary obstruction. The presence of excessive urobilinogen can precede the onset of jaundice and forms a simple and sensitive test of minimal hepatocellular damage or of the presence of haemolysis.

- Estimation of total serum bilirubin: Normal value 5-17 mmol/l.

- Estimation of serum enzyme concentration: Hepatocellular damage is accompanied by a raised level of a number of enzymes, in particular of g-glutamyl transpeptidase, alanine amino-transferase (glutamic pyruvic transaminase) and aspartate amino-transferase (glutamic oxalo-acetic transaminase), and by a moderately raised level of alkaline phosphatase. An increasing level of alkaline phosphatase is indicative of an obstructive lesion.

- Determination of plasma protein concentration and electrophoretic pattern: Hepatocellular damage is accompanied by a fall in plasma albumin and a differential rise in the globulin fractions, in particular in g-globulin. These changes form the basis for the flocculation tests of liver function.

- Bromsulphthalein excretion test: This is a sensitive test of early cellular damage, and is of value in detecting its presence in the absence of jaundice.

- Immunological tests: Estimation of the levels of immunoglobulins and detection of autoantibodies is of value in the diagnosis of certain forms of chronic liver disease. The presence of hepatitis B surface antigen is indicative of serum hepatitis and the presence of alpha-fetoprotein suggests a hepatoma.

- Haemoglobin estimation, red cell indices and report on blood film.

Other tests used in the diagnosis of liver disease include scanning by means of ultrasound or radio-isotope uptake, needle biopsy for histological examination and peritoneoscopy. Ultrasound examination provides a simple, safe, non-invasive diagnostic technique but which requires skill in application.

Occupational disorders

Infections. Schistosomiasis is a widespread and serious parasitic infection which may give rise to chronic hepatic disease. The ova produce inflammation in the portal zones of the liver, followed by fibrosis. The infection is occupational where workers have to be in contact with water infested with the free-swimming cercariae.

Hydatid disease of the liver is common in sheep-raising communities with poor hygienic standards where people are in close contact with the dog, the definitive host, and sheep, the intermediate host for the parasite, Echinococcus granulosus. When a person becomes the intermediate host, a hydatid cyst may form in the liver giving rise to pain and swelling, which may be followed by infection or rupture of the cyst.

Weil’s disease may follow contact with water or damp earth contaminated by rats harbouring the causative organism, Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae. It is an occupational disease of sewer workers, miners, workers in rice-fields, fishmongers and butchers. The development of jaundice some days after the onset of fever forms only one stage of a disease which also involves the kidney.

A number of viruses give rise to hepatitis, the most common being virus type A (HAV) causing acute infective hepatitis and virus type B (HBV) or serum hepatitis. The former, which is responsible for world-wide epidemics, is spread by the faecal-oral route, is characterized by febrile jaundice with liver cell injury and is usually followed by recovery. Type B hepatitis is a disease with a more serious prognosis. The virus is readily transmitted following skin or venipuncture, or transfusion with infected blood products and has been transmitted by drug addicts using the parenteral route, by sexual, especially homosexual contact or by any close personal contact, and also by blood-sucking arthropods. Epidemics have occurred in dialysis and organ transplant units, laboratories and hospital wards. Patients on haemodialysis and those in oncology units are particularly liable to become chronic carriers and hence provide a reservoir of infection. The diagnosis can be confirmed by the identification of an antigen in the serum originally called Australia antigen but now termed hepatitis B surface antigen HBsAg. Serum containing the antigen is highly infectious. Type B hepatitis is an important occupational hazard for health care personnel, especially for those working in clinical laboratories and on dialysis units. High levels of serum positivity have been found in pathologists and surgeons, but low in doctors without patient contact. There is also a hepatitis virus non-A, non-B, identified as hepatitis virus C (HCV). Other hepatitis virus types are likely to be still unidentified. The delta virus cannot cause hepatitis independently but it acts in conjunction with the hepatitis B virus. Chronic virus hepatitis is an important aetiology of liver cirrhosis and cancer (malignant hepatoma).

Yellow fever is an acute febrile illness resulting from infection with a Group B arbovirus transmitted by culicine mosquitoes, in particular Aedes aegypti. It is endemic in many parts of West and Central Africa, in tropical South America and some parts of the West Indies. When jaundice is prominent, the clinical picture resembles infective hepatitis. Falciparum malaria and relapsing fever may also give rise to high fever and jaundice and require careful differentiation.

Toxic conditions. Excessive red blood cell destruction giving rise to haemolytic jaundice may result from exposure to arsine gas, or the ingestion of haemolytic agents such as phenylhydrazine. In industry, arsine may be formed whenever nascent hydrogen is formed in the presence of arsenic, which may be an unsuspected contaminant in many metallurgical processes.

Many exogenous poisons interfere with liver-cell metabolism by inhibiting enzyme systems, or may damage or even destroy the parenchymal cells, interfering with the excretion of conjugated bilirubin and giving rise to jaundice. The injury caused by carbon tetrachloride may be taken as a model for direct hepatotoxicity. In mild cases of poisoning, dyspeptic symptoms may be present without jaundice, but liver damage is indicated by the presence of excess urobilinogen in the urine, raised serum amino-transferase (transaminase) levels and impaired bromsulphthalein excretion. In more severe cases the clinical features resemble those of acute infective hepatitis. Loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain are followed by a tender, enlarged liver and jaundice, with pale stools and dark urine. An important biochemical feature is the high level of serum amino-transferase (transaminase) found in these cases. Carbon tetrachloride has been widely used in dry cleaning, as a constituent of fire extinguishers and as an industrial solvent.

Many other halogenated hydrocarbons have similar hepatotoxic properties. Those of the aliphatic series which damage the liver are methyl chloride, tetrachloroethane, and chloroform. In the aromatic series the nitrobenzenes, dinitrophenol, trinitrotoluene and rarely toluene, the chlorinated naphthalenes and chlorinated diphenyl may be hepatotoxic. These compounds are used variously as solvents, degreasers and refrigerants, and in polishes, dyes and explosives. While exposure may produce parenchymal cell damage with an illness not dissimilar to infectious hepatitis, in some cases (e.g., following exposure to trinitrotoluene or tetrachlorethane) the symptoms may become severe with high fever, rapidly increasing jaundice, mental confusion and coma with a fatal termination from massive necrosis of the liver.

Yellow phosphorus is a highly poisonous metalloid whose ingestion gives rise to jaundice which may have a fatal termination. Arsenic, antimony and ferrous iron compounds may also give rise to liver damage.

Exposure to vinyl chloride in the polymerization process for the production of polyvinyl chloride has been associated with the development of hepatic fibrosis of a non-cirrhotic type together with splenomegaly and portal hypertension. Angiosarcoma of the liver, a rare and highly malignant tumour developed in a small number of exposed workers. Exposure to vinyl chloride monomer, in the 40-odd years preceding the recognition of angiosarcoma in 1974, had been high, especially in men engaged in the cleaning of the reaction vessels, in whom most of the cases occurred. During that period the TLV for vinyl chloride was 500 ppm, subsequently reduced to 5 ppm (10 mg/m3). While liver damage was first reported in Russian workers in 1949, attention was not paid to the harmful effects of vinyl chloride exposure until the discovery of Raynaud’s syndrome with sclerodermatous changes and acro-osteolysis in the 1960s.

Hepatic fibrosis in vinyl chloride workers can be occult, for as parenchymal liver function can be preserved, conventional liver function tests may show no abnormality. Cases have come to light following haematemesis from the associated portal hypertension, the discovery of thrombocytopoenia associated with splenomegaly or the development of angiosarcoma. In surveys of vinyl chloride workers, a full occupational history including information on alcohol and drug consumption should be taken, and the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody determined. Hepatosplenomegaly may be detected clinically, by radiography or more precisely by grey scale ultrasonography. The fibrosis in these cases is of a periportal type, with a mainly presinusoidal obstruction to portal flow, attributed to an abnormality of the portal vein radicles or the hepatic sinusoids and giving rise to portal hypertension. The favourable progress of workers who have undergone portocaval shunt operations following haematemesis is likely to be attributed to the sparing of the liver parenchymal cells in this condition.

Fewer than 200 cases of angiosarcoma of the liver which fulfil current diagnostic criteria have been reported. Less than half of these have occurred in vinyl chloride workers, with an average duration of exposure of 18 years, range 4-32 years. In Britain, a register set up in 1974 has collected 34 cases with acceptable diagnostic criteria. Two of these occurred in vinyl chloride workers, with possible exposure in four others, eight were attributable to past exposure to thorotrast and one to arsenical medication. Thorium dioxide, used in the past as a diagnostic aid, is now responsible for new cases of angiosarcoma and hepatoma. Chronic arsenic intoxication, following medication or as an occupational disease among vintners in the Moselle has also been followed by angiosarcoma. Non-cirrhotic perisinusoidal fibrosis has been observed in chronic arsenic intoxication, as in vinyl chloride workers.

Aflatoxin, derived from a group of moulds, in particular Aspergillus flavus, gives rise to liver cell damage, cirrhosis and liver cancer in experimental animals. The frequent contamination of cereal crops, particularly on storage in warm, humid conditions, with A. flavus, may explain the high incidence of hepatoma in certain parts of the world, especially in tropical Africa. In industrialized countries hepatoma is uncommon, more often developing in cirrhotic livers. In a proportion of cases HBsAg antigen has been present in the serum and some cases have followed treatment with androgens. Hepatic adenoma has been observed in women taking certain oral contraceptive formulations.

Alcohol and cirrhosis. Chronic parenchymal liver disease may take the form of chronic hepatitis or of cirrhosis. The latter condition is characterized by cellular damage, fibrosis and nodular regeneration. While in many cases the aetiology is unknown, cirrhosis may follow viral hepatitis, or acute massive necrosis of the liver, which itself may result from drug ingestion or industrial chemical exposure. Portal cirrhosis is frequently associated with excessive alcohol consumption in industrialized countries such as France, Britain and the United States, although multiple risk factors may be involved to explain variation in susceptibility. While its mode of action is unknown, liver damage is primarily dependent on the amount and duration of drinking. Workers who have easy access to alcohol are at greatest risk of developing cirrhosis. Among the occupations with the highest mortality from cirrhosis are bartenders and publicans, restaurateurs, seafarers, company directors and medical practitioners.

Fungi. Mushrooms of the amanita species (e.g., Amanita phalloides) are highly toxic. Ingestion is followed by gastro-intestinal symptoms with watery diarrhoea and after an interval by acute liver failure due to centrizonal necrosis of the parenchyma.

Drugs. A careful drug history should always be taken before attributing liver damage to an industrial exposure, for a variety of drugs are not only hepatotoxic, but are capable of enzyme induction which may alter the liver’s response to other exogenous agents. Barbiturates are potent inducers of liver microsomal enzymes, as are some food additives and DDT.

The popular analgesic acetaminophen (paracetamol) gives rise to hepatic necrosis when taken in overdose. Other drugs with a predictable dose-related direct toxic action on the liver cell are hycanthone, cytotoxic agents and tetracyclines (though much less potent). Several antituberculous drugs, in particular isoniazid and para-aminosalicylic acid, certain monoamine oxidase inhibitors and the anaesthetic gas halothane may also be hepatotoxic in some hypersensitive individuals.

Phenacetin, sulphonamides and quinine are examples of drugs which may give rise to a mild haemolytic jaundice, but again in hypersensitive subjects. Some drugs may give rise to jaundice, not by damaging the liver cell, but by damaging the fine biliary ducts between the cells to give rise to biliary obstruction (cholestatic jaundice). The steroid hormones methyltestosterone and other C-17 alkyl-substituted compounds of testosterone are hepatotoxic in this way. It is important to determine, therefore, whether a female worker is taking an oral contraceptive in the evaluation of a case of jaundice. The epoxy resin hardener 4,4´-diamino-diphenylmethane led to an epidemic of cholestatic jaundice in England following ingestion of contaminated bread.

Several drugs have given rise to what appears to be a hypersensitive type of intrahepatic cholestasis, as it is not dose related. The phenothiazine group, and in particular chlorpromazine are associated with this reaction.

Preventive Measures

Workers who have any disorder of the liver or gall bladder, or a past history of jaundice, should not handle or be exposed to potentially hepatotoxic agents. Similarly, those who are receiving any drug which is potentially injurious to the liver should not be exposed to other hepatic poisons, and those who have received chloroform or trichlorethylene as an anaesthetic should avoid exposure for a subsequent interval. The liver is particularly sensitive to injury during pregnancy, and exposure to potentially hepatotoxic agents should be avoided at this time. Workers who are exposed to potentially hepatotoxic chemicals should avoid alcohol. The general principle to be observed is the avoidance of a second potentially hepatotoxic agent where there has to be exposure to one. A balanced diet with an adequate intake of first class protein and essential food factors affords protection against the high incidence of cirrhosis seen in some tropical countries. Health education should stress the importance of moderation in the consumption of alcohol in protecting the liver from fatty infiltration and cirrhosis. The maintenance of good general hygiene is invaluable in protecting against infections of the liver like hepatitis, hydatid disease and schistosomiasis.

Control measures for type B hepatitis in hospitals include precautions in the handling of blood samples in the ward; adequate labelling and safe transmission to the laboratory; precautions in the laboratory, with the prohibition of mouth pipetting; the wearing of protective clothing and disposable gloves; prohibition of eating, drinking or smoking in areas where infectious patients or blood samples might be handled; extreme care in the servicing of non-disposable dialysis equipment; surveillance of patients and staff for hepatitis and mandatory screening at intervals for the presence of HBsAg antigen. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B viruses is an efficient method to prevent infection in high risk occupations.

Mouth and Teeth

The mouth is the portal of entry to the digestive system and its functions are, primarily, the chewing and swallowing of food and the partial digestion of starches by means of salivary enzymes. The mouth also participates in vocalizing and may replace or complement the nose in respiration. Due to its exposed position and the functions it fulfils, the mouth is not only a portal of entry but also an area of absorption, retention and excretion for toxic substances to which the body is exposed. Factors which lead to respiration via the mouth (nasal stenoses, emotional situations) and increased pulmonary ventilation during effort, promote either the penetration of foreign substances via this route, or their direct action on the tissues in the buccal cavity.

Respiration through the mouth promotes:

- greater penetration of dust into the respiratory tree since the buccal cavity has a retention quotient (impingement) of solid particles much lower than that of the nasal cavities

- dental abrasion in workers exposed to large dust particles, dental erosion in workers exposed to strong acids, caries in workers exposed to flour or sugar dust, etc.

The mouth may constitute the route of entry of toxic substances into the body either by accidental ingestion or by slow absorption. The surface area of the buccal mucous membranes is relatively small (in comparison with that of the respiratory system and gastro-intestinal system) and foreign substances will remain in contact with these membranes for only a short period. These factors considerably limit the degree of absorption even of substances which are highly soluble; nevertheless, the possibility of absorption does exist and is even exploited for therapeutic purposes (perlingual absorption of drugs).

The tissues of the buccal cavity may often be the site of accumulation of toxic substances, not only by direct and local absorption, but also by transport via the bloodstream. Research using radioactive isotopes has shown that even the tissues which seem metabolically the most inert (such as dental enamel and dentine) have a certain accumulative capacity and a relatively active turnover for certain substances. Classical examples of storage are various discolorations of the mucous membranes (gingival lines) which often provide valuable diagnostic information (e.g. lead).

Salivary excretion is of no value in the elimination of toxic substances from the body since the saliva is swallowed and the substances in it are once more absorbed into the system, thus forming a vicious circle. Salivary excretion has, on the other hand, a certain diagnostic value (determination of toxic substances in the saliva); it may also be of importance in the pathogenesis of certain lesions since the saliva renews and prolongs the action of toxic substances on the buccal mucous membrane. The following substances are excreted in the saliva: various heavy metals, the halogens (the concentration of iodine in the saliva may be 7-700 times greater than that in plasma), the thiocyanates (smokers, workers exposed to hydrocyanic acid and cyanogen compounds), and a wide range of organic compounds (alcohols, alkaloids, etc.).

Aetiopathogenesis and Clinical Classification

Lesions of the mouth and teeth (also called stomatological lesions) of occupational origin may be caused by:

- physical agents (acute traumata and chronic microtraumata, heat, electricity, radiations, etc.)

- chemical agents which affect the tissues of the buccal cavity directly or by means of systemic changes

- biological agents (viruses, bacteria, mycetes).

However, when dealing with mouth and teeth lesions of occupational origin, a classification based on topographical or anatomical location is preferred to one employing aetiopathogenic principles.

Lips and cheeks. Examination of the lips and cheeks may reveal: pallor due to anaemia (benzene, lead poisoning, etc.), cyanosis due to acute respiratory insufficiency (asphyxia) or chronic respiratory insufficiency (occupational diseases of the lungs), cyanosis due to methaemoglobinaemia (nitrites and organic nitro-compounds, aromatic amines), cherry-red colouring due to acute carbon monoxide poisoning, yellow colouring in cases of acute poisoning with picric acid, dinitrocresol, or in a case of hepatotoxic jaundice (phosphorus, chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides, etc.). In argyrosis, there is brown or grey-bluish coloration caused by the precipitation of silver or its insoluble compounds, especially in areas exposed to light.

Occupational disorders of the lips include: dyskeratoses, fissures and ulcerations due to the direct action of caustic and corrosive substances; allergic contact dermatitis (nickel, chrome) which may also include the dermatitis found in tobacco industry workers; microbial eczemas resulting from the use of respiratory protective equipment where the elementary rules of hygiene have not been observed; lesions caused by anthrax and glanders (malignant pustules and cancroid ulcer) of workers in contact with animals; inflammation due to solar radiation and found among agricultural workers and fishermen; neoplastic lesions in persons handling carcinogenic substances; traumatic lesions; and chancre of the lip in glassblowers.

Teeth. Discoloration caused by the deposition of inert substances or due to the impregnation of the dental enamel by soluble compounds is of almost exclusively diagnostic interest. The important colourings are as follows: brown, due to the deposition of iron, nickel and manganese compounds; greenish-brown due to vanadium; yellowish-brown due to iodine and bromine; golden-yellow, often limited to gingival lines, due to cadmium.

Of greater importance is dental erosion of mechanical or chemical origin. Even nowadays it is possible to find dental erosions of mechanical origin in certain craftsmen (caused by holding nails or string, etc., in the teeth) which are so characteristic that they can be considered occupational stigmata. Lesions caused by abrasive dusts have been described in grinders, sandblasters, stone industry workers and precious stone workers. Prolonged exposure to organic and inorganic acids will often cause dental lesions occurring mainly on the labial surface of the incisors (rarely on the canines); these lesions are initially superficial and limited to the enamel but later become deeper and more extensive, reaching the dentine and resulting in solubilization and mobilization of calcium salts. The localization of these erosions to the anterior surface of the teeth is due to the fact that when the lips are open it is this surface which is the most exposed and which is deprived of the natural protection offered by the buffer effect of saliva.

Dental caries is such a frequent and widespread disease that a detailed epidemiological study is required to determine whether the condition is really of occupational origin. The most typical example is that of the caries found in workers exposed to flour and sugar dust (flourmillers, bakers, confectioners, sugar industry workers). This is a soft caries which develops rapidly; it starts at the base of the tooth (rampant caries) and immediately progresses to the crown; the affected sides blacken, the tissue is softened and there is considerable loss of substance and finally the pulp is affected. These lesions begin after a few years of exposure and their severity and extent increases with the duration of this exposure. X rays may also cause rapidly developing dental caries which usually commences at the base of the tooth.

In addition to pulpites due to dental caries and erosion, an interesting aspect of pulp pathology is barotraumatic odontalgia, i.e., pressure-induced toothache. This is caused by the rapid development of gas dissolved in the pulp tissue following sudden atmospheric decompression: this is a common symptom in the clinical manifestations observed during rapid climbing in aircrafts. In the case of persons suffering from septic-gangrenous pulpites, where gaseous material is already present, this toothache may commence at an altitude of 2,000-3,000 m.

Occupational fluorosis does not lead to dental pathology as is the case with endemic fluorosis: fluorine causes dystrophic changes (mottled enamel) only when the period of exposure precedes the eruption of permanent teeth.

Mucous membrane changes and stomatitis. Of definite diagnostic value are the various discolorations of the mucous membranes due to the impregnation or precipitation of metals and their insoluble compounds (lead, antimony, bismuth, copper, silver, arsenic). A typical example is Burton’s line in lead poisoning, caused by the precipitation of lead sulphide following the development in the oral cavity of hydrogen sulphide produced by the putrefaction of food residues. It has not been possible to reproduce Burton’s line experimentally in herbivorous animals.

There is a very curious discoloration in the lingual mucous membrane of workers exposed to vanadium. This is due to impregnation by vanadium pentoxide which is subsequently reduced to trioxide; the discoloration cannot be cleaned away but disappears spontaneously a few days after termination of exposure.

The oral mucous membrane can be the site of severe corrosive damage caused by acids, alkalis and other caustic substances. Alkalis cause maceration, suppuration and tissue necrosis with the formation of lesions which slough off easily. Ingestion of caustic or corrosive substances produces severe ulcerative and very painful lesions of the mouth, oesophagus and stomach, which may develop into perforations and frequently leave scars. Chronic exposure favours the formation of inflammation, fissures, ulcers and epithelial desquamation of the tongue, palate and other parts of the oral mucous membranes. Inorganic and organic acids have a coagulating effect on proteins and cause ulcerous, necrotic lesions which heal with contractive scarring. Mercury chloride and zinc chloride, certain copper salts, alkaline chromates, phenol and other caustic substances produce similar lesions.

A prime example of chronic stomatitis is that caused by mercury. It commences gradually, with discreet symptoms and a prolonged course; the symptoms include excessive saliva, metallic taste in the mouth, bad breath, slight gingival reddening and swelling, and these constitute the first phase of periodontitis leading towards loss of teeth. A similar clinical picture is found in stomatitis due to bismuth, gold, arsenic, etc.

Salivary glands. Increased salivary secretion has been observed in the following cases:

- in a variety of acute and chronic stomatites which is due mainly to the irritant action of the toxic substances and may, in certain cases, be extremely intense. For example, in cases of chronic mercurial poisoning, this symptom is so prominent and occurs at such an early stage that English workers have called this the “salivation disease”.

- in cases of poisoning in which there is central nervous system involvement—as is the case in manganese poisoning. However, even in the case of chronic mercurial poisoning, salivary gland hyperactivity is thought to be, at least in part, nervous in origin.

- in cases of acute poisoning with organophosphorus pesticides which inhibit cholinesterases.

There is reduction in salivary secretion in severe thermoregulation disorders (heatstroke, acute dinitrocresol poisoning), and in serious disorders of water and electrolyte balance during toxic hepatorenal insufficiency.

In cases of acute or chronic stomatitis, the inflammatory process may, sometimes, affect the salivary glands. In the past there have been reports of “lead parotitis”, but this condition has become so rare nowadays that doubts about its actual existence seem justified.

Maxillary bones. Degenerative, inflammatory and productive changes in the skeleton of the mouth may be caused by chemical, physical and biological agents. Probably the most important of the chemical agents is white or yellow phosphorus which causes phosphorus necrosis of the jaw or “phossy jaw”, at one time a distressing disease of match industry workers. The absorption of phosphorus is facilitated by the presence of gingival and dental lesions, and produces, initially, productive periosteal reaction followed by destructive and necrotic phenomena which are activated by bacterial infection. Arsenic also causes ulceronecrotic stomatitis which may have further bone complications. The lesions are limited to the roots in the jaw, and lead to the development of small sheets of dead bones. Once the teeth have fallen out and the dead bone eliminated, the lesions have a favourable course and nearly always heal.

Radium was the cause of maxillary osteonecrotic processes observed during the First World War in workers handling luminous compounds. In addition, damage to the bone may also be caused by infection.

Preventive Measures

A programme for the prevention of mouth and teeth diseases should be based on the following four main principles:

- application of measures of industrial hygiene and preventive medicine including monitoring of workplace environment, analysis of production processes, elimination of hazards in the environment, and, where necessary, the use of personal protective equipment

- education of workers in the need for scrupulous oral hygiene—in many cases it has been found that lack of oral hygiene may reduce resistance to general and localized occupational diseases

- a careful check on the mouth and teeth when workers undergo pre-employment or periodical medical examinations

- early detection and treatment of any mouth or teeth disease, whether of an occupational nature or not.

Digestive System

The digestive system exerts a considerable influence on the efficiency and work capacity of the body, and acute and chronic illnesses of the digestive system are among the commonest causes of absenteeism and disablement. In this context, the occupational physician may be called upon in either of the following ways to offer suggestions concerning hygiene and nutritional requirements in relation to the particular needs of a given occupation: to assess the influence that factors inherent in the occupation may have either in producing morbid conditions of the digestive system, or in aggravating others that may pre-exist or be otherwise independent of the occupation; or to express an opinion concerning general or specific fitness for the occupation.

Many of the factors that are harmful to the digestive system may be of occupational origin; frequently a number of factors act in concert and their action may be facilitated by individual predisposition. The following are among the most important occupational factors: industrial poisons; physical agents; and occupational stress such as tension, fatigue, abnormal postures, frequent changes in work tempo, shift work, night work and unsuitable eating habits (quantity, quality and timing of meals).

Chemical Hazards

The digestive system may act as a portal for the entry of toxic substances into the body, although its role here is normally much less important than that of the respiratory system which has an absorption surface area of 80-100 m2 whereas the corresponding figure for the digestive system does not exceed 20 m2. In addition, vapours and gases entering the body by inhalation reach the bloodstream and hence the brain without meeting any intermediate defence; however, a poison that is ingested is filtered and, to some degree, metabolized by the liver before reaching the vascular bed. Nevertheless, the organic and functional damage may occur both during entry into and elimination from the body or as a result of accumulation in certain organs. This damage suffered by the body may be the result of the action of the toxic substance itself, its metabolites or the fact that the body is depleted of certain essential substances. Idiosyncrasy and allergic mechanisms may also play a part. The ingestion of caustic substances is still a fairly common accidental occurrence. In a retrospective study in Denmark, the annual incidence was of 1/100,000 with an incidence of hospitalization of 0.8/100,000 adult person-years for oesophageal burns. Many household chemicals are caustic.

Toxic mechanisms are highly complex and may vary considerably from substance to substance. Some elements and compounds used in industry cause local damage in the digestive system affecting, for example, the mouth and neighbouring area, stomach, intestine, liver or pancreas.

Solvents have particular affinity for lipid-rich tissues. The toxic action is generally complex and different mechanisms are involved. In the case of carbon tetrachloride, liver damage is thought to be mainly due to toxic metabolites. In the case of carbon disulphide, gastrointestinal involvement is attributed to the specific neurotropic action of this substance on the intramural plexus whilst liver damage seems to be more due to the solvent’s cytotoxic action, which produces changes in lipoprotein metabolism.

Liver damage constitutes an important part of the pathology of exogenic poisons since the liver is the prime organ in metabolizing toxic agents and acts with the kidneys in detoxication processes. The bile receives from the liver, either directly or after conjugation, various substances that can be reabsorbed in the enterohepatic cycle (for instance, cadmium, cobalt, manganese). Liver cells participate in oxidation (e.g., alcohols, phenols, toluene), reduction, (e.g., nitrocompounds), methylation (e.g., selenic acid), conjugation with sulphuric or glucuronic acid (e.g., benzene), acetylation (e.g., aromatic amines). Kupffer cells may also intervene by phagocytosing the heavy metals, for example.

Severe gastro-intestinal syndromes, such as those due to phosphorus, mercury or arsenic are manifested by vomiting, colic, and bloody mucus and stools and may be accompanied by liver damage (hepatomegalia, jaundice). Such conditions are relatively rare nowadays and have been superseded by occupational intoxications which develop slowly and even insidiously; consequently liver damage, in particular, may often be insidious too.

Infectious hepatitis deserves particular mention; it may be related to a number of occupational factors (hepatotoxic agents, heat or hot work, cold or cold work, intense physical activity, etc.), may have an unfavourable course (protracted or persistent chronic hepatitis) and may easily result in cirrhosis. It frequently occurs with jaundice and thus creates diagnostic difficulties; moreover, it presents difficulties of prognosis and estimation of the degree of recovery and hence of fitness for resumption of work.

Although the gastro-intestinal tract is colonized by abundant microflora which have important physiological functions in human health, an occupational exposure may give rise to occupational infections. For example, abattoir workers may be at risk to contract a helicobacter infection. This infection may often be symptomless. Other important infections include the Salmonella and Shigella species, which must be also controlled in order to maintain product safety, such as in the food industry and in catering services.

Smoking and alcohol consumption are the major risks for oesophageal cancer in industrialized countries, and occupational aetiology is of lesser importance. However, butchers and their spouses seem to be at elevated risk of colorectal cancer.

Physical Factors

Various physical agents may cause digestive system syndromes; these include direct or indirect disabling traumata, ionizing radiations, vibration, rapid acceleration, noise, very high and low temperatures or violent and repeated climatic changes. Burns, especially if extensive, may cause gastric ulceration and liver damage, perhaps with jaundice. Abnormal postures or movements may cause digestive disorders especially if there are predisposing conditions such as para-oesophageal hernia, visceroptosis or relaxatio diaphragmatica; in addition, extra-digestive reflexes such as heartburn may occur where digestive disorders are accompanied by autonomic nervous system or neuro-psychological troubles. Troubles of this type are common in modern work situations and may themselves be the cause of gastro-intestinal dysfunction.

Occupational Stress

Physical fatigue may also disturb digestive functions, and heavy work may cause secretomotor disorders and dystrophic changes, especially in the stomach. Persons with gastric disorders, especially those who have undergone surgery are limited in the amount of heavy work they can do, if only because heavy work requires higher levels of nutrition.

Shift work may cause important changes in eating habits with resultant functional gastro-intestinal problems. Shift work may be associated with elevated blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels, as well as increased gamma-glutamyltransferase activity in serum.

Nervous gastric dyspepsia (or gastric neurosis) seems to have no gastric or extragastric cause at all, nor does it result from any humoral or metabolic disorder; consequently, it is considered to be due to a primitive disorder of the autonomic nervous system, sometimes associated with excessive mental exertion or emotional or psychological stress. The gastric disorder is often manifested by neurotic hypersecretion or by hyperkinetic or atonic neurosis (the latter frequently associated with gastroptosis). Epigastric pain, regurgitation and aerophagia may also come under the heading of neurogastric dyspepsia. Elimination of the deleterious psychological factors in the work environment may lead to remission of symptoms.

Several observations point to an increased frequency of peptic ulcers among people carrying responsibilities, such as supervisors and executives, workers engaged in very heavy work, newcomers to industry, migrant workers, seafarers and workers subject to serious socio-economic stress. However, many people suffering the same disorders lead a normal professional life, and statistical evidence is lacking. In addition to working conditions drinking, smoking and eating habits, and home and social life all play a part in the development and prolongation of dyspepsia, and it is difficult to determine what part each one plays in the aetiology of the condition.

Digestive disorders have also been attributed to shift work as a consequence of frequent changes of eating hours and poor eating at workplaces. These factors can aggravate pre-existing digestive troubles and release a neurotic dyspepsia. Therefore, workers should be assigned to shift work only after medical examination.

Medical Supervision

It can be seen that the occupational health practitioner is faced with many difficulties in the diagnosis and estimation of digestive system complaints (due inter alia to the part played by deleterious non-occupational factors) and that his or her responsibility in prevention of disorders of occupational origin is considerable.

Early diagnosis is extremely important and implies periodical medical examinations and supervision of the working environment, especially when the level of risk is high.

Health education of the general public, and of workers in particular, is a valuable preventive measure and may yield substantial results. Attention should be paid to nutritional requirements, choice and preparation of foodstuffs, the timing and size of meals, proper chewing and moderation in the consumption of rich foods, alcohol and cold drinks, or complete elimination of these substances from the diet.

Biological Hazards

“A biological hazardous material can be defined as a biological material capable of self-replication that can cause harmful effects in other organisms, especially humans” (American Industrial Hygiene Association 1986).

Bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa are among the biological hazardous materials that can harm the cardiovascular system through contact that is intentional (introduction of technology-related biological materials) or unintentional (non-technology-related contamination of work materials). Endotoxins and mycotoxins may play a role in addition to the infectious potential of the micro-organism. They can themselves be a cause or contributing factor in a developing disease.

The cardiovascular system can either react as a complication of an infection with a localized organ participation—vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels), endocarditis (inflammation of the endocardium, primarily from bacteria, but also from fungus and protozoa; acute form can follow septic occurrence; subacute form with generalization of an infection), myocarditis (heart muscle inflammation, caused by bacteria, viruses and protozoa), pericarditis (pericardium inflammation, usually accompanies myocarditis), or pancarditis (simultaneous appearance of endocarditis, myocarditis and pericarditis)—or be drawn as a whole into a systemic general illness (sepsis, septic or toxic shock).

The participation of the heart can appear either during or after the actual infection. As pathomechanisms the direct germ colon- ization or toxic or allergic processes should be considered. In addition to type and virulence of the pathogen, the efficiency of the immune system plays a role in how the heart reacts to an infection. Germ-infected wounds can induce a myo- or endo- carditis with, for example, streptococci and staphylococci. This can affect virtually all occupational groups after a workplace accident.

Ninety per cent of all traced endocarditis cases can be attributed to strepto- or staphylococci, but only a small portion of these to accident-related infections.

Table 1 gives an overview of possible occupation-related infectious diseases that affect the cardiovascular system.

Table 1. Overview of possible occupation-related infectious diseases that affect the cardiovascular system

|

Disease |

Effect on heart |

Occurrence/frequency of effects on heart in case of disease |

Occupational risk groups |

|

AIDS/HIV |

Myocarditis, Endocarditis, Pericarditis |

42% (Blanc et al. 1990); opportunistic infections but also by the HIV virus itself as lymphocytic myocarditis (Beschorner et al. 1990) |

Personnel in health and welfare services |

|

Aspergillosis |

Endocarditis |

Rare; among those with suppressed immune system |

Farmers |

|

Brucellosis |

Endocarditis, Myocarditis |

Rare (Groß, Jahn and Schölmerich 1970; Schulz and Stobbe 1981) |

Workers in meatpacking and animal husbandry, farmers, veterinarians |

|

Chagas’ disease |

Myocarditis |

Varying data: 20% in Argentina (Acha and Szyfres 1980); 69% in Chile (Arribada et al. 1990); 67% (Higuchi et al. 1990); chronic Chagas’ disease always with myocarditis (Gross, Jahn and Schölmerich 1970) |

Business travelers to Central and South America |

|

Coxsackiessvirus |

Myocarditis, Pericarditis |

5% to 15% with Coxsackie-B virus (Reindell and Roskamm 1977) |

Personnel in health and welfare services, sewer workers |

|

Cytomegaly |

Myocarditis, Pericarditis |

Extremely rare, especially among those with suppressed immune system |

Personnel who work with children (especially small children), in dialysis and transplant departments |

|

Diphtheria |

Myocarditis, Endocarditis |