Tobacco Cultivation

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) is a unique plant with its characteristic commercial component, nicotine, contained in its leaves. Although cotton is grown on more surface area, tobacco is the most widely grown nonfood crop in the world; it is produced in approximately 100 countries and on every continent. Tobacco is consumed around the world as cigarettes, cigars, chewing or smoking tobaccos and snuff. However, over 80% of world production is consumed as cigarettes, currently estimated at nearly 5.6 trillion annually. China, the United States, Brazil and India produced over 60% of total world production in 1995, which was estimated at 6.8 million tonnes.

The specific uses of tobacco by manufacturers are determined by the chemical and physical properties of the cured leaves, which in turn are determined by interactions among genetic, soil, climatic and cultural management factors. Therefore, many kinds of tobacco are grown in the world, some with rather specific local, commercial uses in one or more tobacco products. In the United States alone, tobacco is categorized into seven major classes which contain a total of 25 different tobacco types. The specific techniques used to produce tobacco vary among and within tobacco classes in various countries, but cultural manipulation of nitrogen fertilization, plant density, time and height of topping, harvesting and curing are used to favourably influence the usability of the cured leaves for specific products; quality of leaves, however, is highly dependent on prevailing environmental conditions.

Flue-cured, Burley and Oriental tobaccos are the major components of the increasingly popular blended cigarette now consumed worldwide, and represented 57, 11 and 12%, respectively, of world production in 1995. Thus, these tobaccos are widely traded internationally; the United States and Brazil are the major exporters of flue-cured and Burley leaf tobaccos, while Turkey and Greece are the major world suppliers of Oriental tobacco. The world’s largest tobacco producer and cigarette manufacturer, China, currently consumes most of its production internally. Because of increasing demand for the “American” blended cigarette, the United States became the major cigarette exporter in the early 1990s.

Tobacco is a transplanted crop. In most countries, seedlings are started from tiny seeds (about 12,000 per gram) sown by hand on well-prepared soil beds and manually removed for transplanting to the field after reaching a height of 15 to 20 cm. In tropical climates, seed-beds are usually covered with dried plant materials to preserve soil moisture and reduce disturbance of seeds or seedlings by heavy rains. In cooler climates, seed-beds are covered for frost and freeze protection with one of several synthetic materials or with cotton cheesecloth until several days before transplanting. The bed sites are usually treated before seeding with methyl bromide or dazomet to manage most weeds and soil-borne diseases and insects. Herbicides for supplemental grass management are also labelled for use in some countries, but in areas where labour is plentiful and inexpensive, weeds and grasses are often removed by hand. Foliar insects and diseases are usually managed with periodic applications of appropriate pesticides. In the United States and Canada, seedlings are produced primarily in greenhouses covered with plastic and glass, respectively. Seedlings are usually grown in peat- or muck-based media which, in Canada, are steam-sterilized before seeds are sown. In the United States, polystyrene trays are predominantly used to contain the media and are often treated with methyl bromide and/or a chlorine bleach solution between transplant production seasons to protect against fungal diseases. However, only a few pesticides are labelled in the United States for use in tobacco greenhouses, so farmers there depend substantially on proper ventilation, horizontal air movement and sanitation to manage most foliar diseases.

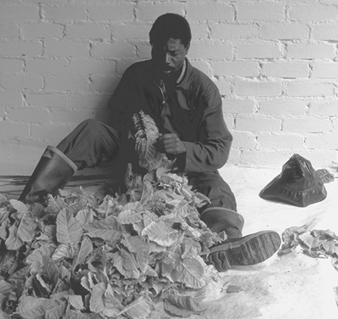

Regardless of the method of transplant production, seedlings are periodically clipped or mowed above the apical meristems for several weeks before transplanting to improve uniformity and survival after transplanting to the field. Clipping is performed mechanically in some developed countries but manually where labour is plentiful (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Manual clipping of tobacco seedlings with shears in Zimbabwe

Gerald Peedin

Depending on availability and cost of labour and equipment, seedlings are manually or mechanically transplanted to well- prepared fields previously treated with one or more pesticides for control of soil pathogens and/or grasses (see figure 2). In order to protect workers from pesticide exposure, pesticides are seldom applied during the transplanting operation, but additional weed and foliar pest management are often needed during subsequent growth and harvesting of the crop. In many countries, varietal tolerance and 2- to 4-year rotations of tobacco with nonhost crops (where sufficient land is available) are widely used to reduce reliance on pesticides. In Zimbabwe, government regulations require seedling beds and stalks/roots in harvested fields to be destroyed by certain dates to reduce the incidence and spread of insect-transmitted viruses.

Figure 2. Mechanical transplanting of flue-cured tobacco in North Carolina (US)

About 4 to 5 hectares per day can be transplanted using ten workers and a four-row transplanter. Six workers are needed for a two-row transplanter and four workers for a one-row transplanter.

Gerald Peedin

Depending upon tobacco type, fields receive relatively moderate-to-high rates of fertilizer nutrients, which are usually applied by hand in developing countries. For proper ripening and curing of flue-cured tobacco, it is necessary for nitrogen absorption to decrease rapidly soon after vegetative growth is complete. Therefore, animal manures are not routinely applied to flue-cured soils, and only 35 to 70 kg per hectare of inorganic nitrogen from commercial fertilizers are applied, depending on soil characteristics and rainfall. Burley and most chewing and cigar tobaccos are usually grown on more fertile soils than those used for flue-cured tobacco, but receive 3 to 4 times more nitrogen to enhance certain desirable characteristics of these tobaccos.

Tobacco is a flowering plant with a central meristem which suppresses growth of axillary buds (suckers) by hormonal action until the meristem begins to produce flowers. For most tobacco types, removal of flowers (topping) before seed maturation and control of subsequent sucker growth are common cultural practices used to improve yields by diverting more growth resources into leaf production. Flowers are removed manually or mechanically (primarily in the United States) and sucker growth retarded in most countries with applications of contact and/or systemic growth regulators. In the United States, suckercides are applied mechanically on flue-cured tobacco, which has the longest harvest season of the tobacco types produced in that country. In underdeveloped countries, suckercides are often applied manually. However, regardless of the chemicals and application methods used, complete control is seldom achieved, and some hand labour is usually needed to remove suckers not controlled by the suckercides.

Harvesting practices vary substantially among tobacco types. Flue-cured, Oriental and cigar wrapper are the only types whose leaves are consistently harvested (primed) in sequence as they ripen (senesce) from the bottom to the top of the plant. As leaves ripen, their surfaces become textured and yellow as chlorophyll degrades. Several leaves are removed from each plant in each of several passes over the field during a period of 6 to 12 weeks after topping, depending on rainfall, temperature, soil fertility and variety. Other tobacco types such as Burley, Maryland, cigar binder and filler, and fire-cured chewing tobaccos are “stalk cut”, meaning that the entire plant is cut off near ground level when most of the leaves are judged to be ripe. For some air-cured types, the lower leaves are primed while the remainder of the plant is stalk cut. Regardless of tobacco type, harvesting and preparation of the leaves for curing and marketing are the most labour-intensive tasks in tobacco production (see figure 3).Harvesting is normally accomplished with manual labour, especially for stalk cutting, which has yet to be totally mechanized (see figure 4). Priming of flue-cured tobacco is now highly mechanized in most developed countries, where labour is scarce and expensive. In the United States, about one-half of the flue-cured type is primed with machines, which requires almost complete weed and sucker control to minimize content of these materials in the cured leaves.

Figure 3. Preparing Oriental tobacco for air-curing soon after hand harvesting

The small leaves are collected on a string by pushing a needle through the central vein of each leaf.

Gerald Peedin

Figure 4. Hand harvesting of flue-cured tobacco by a small farmer in southern Brazil

Some farmers use small tractors rather than oxen to pull sleds or trailers. Over 90% of harvesting and other labour is provided by family members, relatives and/or neighbours.

Gerald Peedin

Proper curing of most tobacco types requires management of temperature and moisture content within the curing structure to regulate the drying rate of green leaves. Flue-curing requires the most sophisticated curing structures because temperature and moisture control follow rather specific schedules, and temperatures reach over 70 °C in the latter stages of curing, which totals only 5 to 8 days. In North America and Western Europe, flue-curing is accomplished primarily in gas- or oil-fired metal (bulk) barns equipped with automatic or semiautomatic temperature- and humidity-control devices. In most other countries, the barn environment is controlled manually and the barns are constructed of wood or bricks and often fired by hand with wood (Brazil) or coal (Zimbabwe). The initial and most important stage of flue-curing is called yellowing, during which chlorophyll is degraded and most carbohydrates are converted to simple sugars, giving cured leaves a characteristic sweet aroma. The leaf cells are then killed with drier and hotter air to stop respiratory losses of sugars. The products of combustion do not contact the leaves. Most other tobacco types are air-cured in barns or sheds without heat, but usually with some means of partial, manual ventilation control. The air-curing process requires 4 to 8 weeks, depending on prevailing environmental conditions and the ability to control humidity within the barn. This longer, gradual process results in cured leaves with low sugar contents. Fire-cured tobacco, used primarily in chewing and snuff products, is basically air-cured but small, open fires using oak or hickory wood are used to periodically “smoke” the leaves to give them a characteristic wood odour and taste and to improve their keeping properties.

The colours of cured leaves and their uniformity within a lot of tobacco are important characteristics used by buyers to determine the usefulness of tobaccos for specific products. Therefore, leaves with undesirable colours (particularly green, black and brown) are usually manually removed by farmers before offering the tobacco for sale (see figure 5).In most countries, the cured tobaccos are further separated into homogeneous lots based on variations in leaf colour, size, texture and other visual characteristics (see figure 6).In some southern African countries, where labour is plentiful and inexpensive and most of the production is exported, a crop may be sorted into 60 or more lots (i.e., grades) before being sold (as in figure 6).Most tobacco types are packaged in bales weighing 50 to 60 kg (100 kg in Zimbabwe) and delivered to the purchaser in the cured form (see figure 7).In the United States, flue-cured tobacco is marketed in burlap sheets averaging about 100 kg each; however, use of bales weighing over 200 kg is currently being evaluated. In most countries, tobacco is produced and sold under contract between the farmer and the purchaser, with predetermined prices for the various grades. In a few large tobacco-producing countries, annual production is controlled by government regulation or by farmer-buyer negotiation, and the tobacco is sold in an auction system with (United States and Canada) or without (Zimbabwe) minimum established prices for the various grades. In the United States, flue-cured or Burley tobacco not sold to commercial buyers is purchased for price support by grower-owned cooperatives and sold later to domestic and foreign buyers. Although some marketing systems have been substantially mechanized, such as that in Zimbabwe (shown in figure 8),.a great deal of manual labour is still required to unload and present the tobacco for sale, remove it from the sale area and load and transport it to the buyer’s processing facilities.

Figure 5. Manual removal of cured Burley leaves from the stalks

Gerald Peedin

Figure 6. Manual separation of cured flue-cured tobacco into homogeneous grades in Zimbabwe.

Gerald Peedin

Figure 7. Loading tobacco bales for transport from the farm to a marketing centre in southern Brazil

Gerald Peedin

Figure 8. Unloading a farmer’s tobacco bales at the auction centre in Zimbabwe, which has the most mechanized and efficient flue-cured marketing system in the world.

Gerald Peedin

Hazards and Their Prevention

The manual labour required to produce and market tobacco varies greatly around the world, depending primarily on the level of mechanization used for transplanting, harvesting and market preparation. Manual labour involves risks of musculoskeletal problems from activities such as transplanting seedlings, application of suckercides, harvesting, separation of the cured tobacco into grades and lifting of tobacco bales. Training in proper lifting methods and provision of ergonomically designed tools can help prevent these problems. Knife injuries may occur during cutting, and tetanus may arise in open wounds. Sharp, well-designed knives and training in their use can reduce the number of injuries.

Mechanization can reduce these risks, but carries risks of injury from the machinery used, including transportation accidents. Well-designed tractors with safety cabs, properly guarded machinery and adequate training can reduce the number of injuries.

Spraying of pesticides and fungicides can involve the risk of chemical exposures. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) Worker Protection Standard requires farmers to protect workers from pesticide-related illness or injury by (1) providing training on pesticide safety, specifically those pesticides used on the farm; (2) providing personal protective equipment (PPE) and clothing and assuming responsibility for their proper use and cleaning, plus ensuring that workers do not enter treated fields during specific time intervals after pesticide application; and (3) providing decontamination sites and emergency assistance in case of exposure. Substitution of less hazardous pesticides should also be done where possible.

Field labourers, usually those not accustomed to working in tobacco fields, sometimes become nauseous and/or dizzy soon after direct contact with green tobacco during harvesting, perhaps because nicotine or other substances are absorbed through the skin. In the United States, the condition is called “green tobacco sickness” and affects a small percentage of workers. Symptoms occur most often when sensitive individuals are harvesting wet tobacco and their clothing and/or exposed skin is in almost continuous contact with green tobacco. The condition is temporary and not known to be serious, but causes some discomfort for several hours after exposure. Suggestions for sensitive workers to minimize exposure during harvesting or other tasks requiring prolonged contact with green tobacco include not starting work until the leaves have dried or wearing lightweight rain gear and waterproof gloves when the leaves are wet; wearing long trousers, long-sleeve shirts and possibly gloves as precautions when working in dry tobacco; and leaving the field and washing immediately if symptoms occur.

Skin diseases may occur in workers handling tobacco leaf in warehouses or barns. Sometimes workers in these storage areas, especially new workers, may develop conjunctivitis and laryngitis.

Other preventive measures include good washing and other sanitary facilities, provision of first aid and medical care, and proper training.

Bamboo and Cane

Adapted from Y.C. Ko’s article, “Bamboo and cane”, “Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety”, 3rd edition.

Bamboo, which is a subfamily of the grasses, exists as more than a thousand different species, but only a few species are cultivated in commercial plantations or nurseries. Bamboos are tree-like or shrubby grasses with woody stems, called culms. They range from small plants with centimetre-thick culms to giant subtropical species up to 30 m tall and 30 cm in diameter. Some bamboos grow at a prodigious rate, up to 16 cm in height per day. Bamboos rarely flower (and when they do, it may be at intervals of 120 years), but they can be cultivated by planting their stalks. Most bamboos came from Asia, where they grow wild in tropical and subtropical areas. Some species have been exported to temperate climates, where they require irrigation and special care during the winter.

Some bamboo species are used as vegetables and may be pickled or preserved. Bamboo has been used as an oral medicine against poisoning since it contains silicic acid which absorbs poison in the stomach. (Silicic acid is now produced synthetically.)

The wood-like properties of bamboo culms have led to their use for many other purposes. Bamboo is used in building houses, with the culms as uprights and the walls and roofs made from split stems or lattice work. Bamboo is also used for making boats and boat masts, rafts, fences, furniture, containers and handicraft products, including umbrellas and walking sticks. Other uses abound: water pipes, wheelbarrow axles, flutes, fishing rods, scaffolding, roller-blinds, ropes, rakes, brooms and weapons such as bows and arrows. In addition, bamboo pulp has been used to make high-quality paper. It is also grown in nurseries and used in gardens as ornamentals, wind breaks and hedges (Recht and Wetterwald 1992).

Cane is sometimes confused with bamboo, but is botanically different and comes from varieties of the rattan palm. Rattan palms grow freely in tropical and subtropical areas, particularly in Southeast Asia. Cane is used to make furniture (especially chairs), baskets, containers and other handicraft products. It is very popular due to its appearance and elasticity. It is frequently necessary to split the stems when cane is used in manufacturing.

Cultivation Processes

The processes for cultivating bamboo include propagation, planting, watering and feeding, pruning and harvesting. Bamboos are propagated in two ways: by planting seeds or by using sections of the rhizome (the underground stem). Some plantations depend upon natural reseeding. Since some bamboos flower infrequently and seeds remain viable only for a couple of weeks, most propagation is accomplished by dividing a large plant that includes the rhizome with culms. Spades, knives, axes or saws are used to divide the plant.

Growers plant bamboo in groves, and planting and replanting bamboo involves digging a hole, placing the plant into the hole and backfilling soil around its rhizomes and roots. About 10 years is required to establish a healthy grove of bamboo. Although not a concern in its native habitat where it rains often, irrigation is necessary when bamboos are grown in drier areas. Bamboo requires a lot of fertilizer, particularly nitrogen. Both animal dung and commercial fertilizer are used. Silica (SiO2) is as important for bamboos as is nitrogen. In natural growth, bamboo gains enough silica naturally by recycling it from shed leaves. In commercial nurseries, shed leaves are left around the bamboo and silica-rich clay minerals such as Bentonite may be added. Bamboos are pruned of old and dead culms to provide room for new growth. In Asian groves, dead culms may be split in the fields to hasten their decay and add to the soil’s humus.

Bamboo is harvested either as a food or for its wood or pulp. Bamboo shoots are harvested for food. They are dug from the soil and cut with a knife or chopped with an axe. The bamboo culms are harvested when they are 3 to 5 years old. Harvesting is timed for when the culms are neither too soft nor too hard. Bamboo culms are harvested for their wood. They are cut or chopped with a knife or an axe, and the cut bamboo may be heated to bend it or split with a knife and mallet, depending upon its end use.

Rattan palm cane is usually harvested from wild trees often in uncultivated mountainous areas. The stems of the plants are cut near the roots, dragged out from thickets and sun-dried. The leaves and the bark are then removed, and the stems are sent for processing.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Venomous snakes present a hazard in plantation groves. Stumbling over bamboo stumps may cause falls, and cuts can lead to tetanus infection. Bird and chicken droppings in bamboo groves can be contaminated with Histoplasma capsulatum (Storch et al. 1980). Working with bamboo culms can lead to knife cuts, particularly when splitting the culms. Sharp edges and the ends of bamboos can cause cuts or punctures. Hyperkeratosis of the palms and fingers has been observed in workers who make bamboo containers. Pesticide exposures are also possible. First aid and medical treatment is required to deal with snake bites. Vaccine and booster vaccine should be used to prevent tetanus.

All cutting knives and saws should be maintained and used with care. Where bird droppings are present, work should be conducted during wet conditions to prevent dust exposure, or respiratory protection should be used.

In harvesting palm cane, workers are exposed to the dangers of remote forests, including snakes and venomous insects. The bark of the tree has thorns that may tear the skin, and workers are exposed to cuts from knives. Gloves should be worn when the stems are handled. Cuts are also a risk during manufacture, and hyperkeratosis of the palms and fingers may often occur among workers, probably because of the friction of the material.

Bark and Sap Production

Some text was revised from the articles “Hemp”, by A. Barbero-Carnicero; “Cork”, by C. de Abeu; “Rubber cultivation”, by the Dunlop Co.; “Turpentine”, by W. Grimm and H. Gries; “Tanning and leather finishing”, by V.P. Gupta; “Spice industry”, by S. Hruby; “Camphor”, by Y. Ko; “Resins”, by J. Kubota; “Jute”, by K.M. Myunt; and “Bark”, by F.J. Wenzel from the 3rd edition of this “Encyclopaedia”.

The term bark refers to the multilayered protective shell covering a tree, shrub or vine. Some herbaceous plants, such as hemp, are also harvested for their bark. Bark is composed of inner and outer bark. Bark starts at the vascular cambium in the inner bark, where cells are generated for the phloem or conductive tissue that transports sugar from the leaves to the roots and other parts of the plant and the sap wood inside the bark layer with vessels that carry water (sap) up from the roots to the plant. The primary purpose of the outer bark is to protect the tree from injury, heat, wind and infection. A great variety of products are extracted from bark and tree sap, as shown in table 1.

Table 1. Bark and sap products and uses

|

Commodity |

Product (tree) |

Use |

|

Resins (inner bark) |

Pine resin, copal, frankincense, myrrh, red resin (climbing palm) |

Varnish, shellac, lacquer Incense, perfume, dye |

|

Oleoresins (sapwood) |

Turpentine Rosin Benzoin Camphor (camphor laurel tree) |

Solvent, thinner, perfume feedstock, disinfectant, pesticide Violin bow treatment, varnish, paint, sealing wax, adhesive, cement, soap Gymnast’s powder Perfume, incense, plastic and film feedstock, lacquers, smokeless powder explosives, perfumes, disinfectants, insect repellents |

|

Latex |

Rubber Gutta-percha |

Tyres, balloons, gaskets, condoms, gloves Insulators, underground and marine cable coatings, golf balls, surgical appliances, some adhesives, chicle/base for chewing gum |

|

Medicines and poisons (bark) |

Witch hazel Cascara Quinine (cinchona) Cherry Pacific yew Curarine Caffeine (yoco vine) Lonchocarpus vine |

Lotions Emetic Anti-malaria medicinal Cough medicine Ovarian cancer treatment Arrow poison Amazonian soft drink Fish asphyxiate |

|

Flavours (bark) |

Cinnamon (cassia tree) Bitters, nutmeg and mace, cloves, sassafras root |

Spice, flavouring Root beer (until linked to liver cancer) |

|

Tannins (bark) |

Hemlock, oak, acacia, wattle, willow, mangrove, mimosa, quebracho, sumach, birch |

Vegetable tanning for heavier leathers, food processing, fruit ripening, beverage (tea, coffee, wine) processing, ink colouring ingredient, dyeing mordants |

|

Cork (outer bark) |

Natural cork (cork oak), reconstituted cork |

Buoy, bottle cap, gasket, cork paper, cork board, acoustic tile, shoe inner sole |

|

Fibre (bark) |

Cloth (birch, tapa, fig, hibiscus, mulberry) Baobab tree (inner) bark Jute (linden family) Bast from flax, hemp (mulberry family), ramie (nettle family) |

Canoe, paper, loincloth, skirt, drapery, wall hanging, rope, fishing net, sack, coarse clothing Hat Hessians, sackings, burlap, twine, carpets, clothing Cordage, linen |

|

Sugar |

Sugar maple syrup (sapwood) Gur (many palm species) |

Condiment syrup Palm sugar |

|

Waste bark |

Bark chips, strips |

Soil conditioner, mulch (chips), garden pathway covering, fiberboard, particleboard, hardboard, chipboard, fuel |

Trees are grown for their bark and sap products either by cultivation or in the wild. Reasons for this choice vary. Cork oak groves have advantages over wild trees, which are contaminated by sand and grow irregularly. The control of a rubber tree leaf rust fungus in Brazil is more effective in the sparse tree spacing of the wild. However, in locations free of this fungus, such as in Asia, plantation groves are very effective for cultivating rubber trees.

Processes

Three broad processes are used in harvesting bark and sap: stripping of bark in sheets, debarking for bulk bark and bark ingredients and the extraction of tree fluids by cutting or tapping.

Bark sheets

Stripping sheets of bark from standing trees is easier when the sap is running or after steam injection between the bark and the wood. Two bark stripping technologies are described below, one for cork and the other for cinnamon.

The cork oak is cultivated in the western Mediterranean basin for cork, and Portugal is the largest cork producer. The cork oak, as well as other trees such as the African baobab tree, share the important feature of regrowing outer bark after its removal. Cork is part of the outer bark that lies beneath the hard outer shell called the rhytidome. The thickness of the cork layer increases year-by-year. After an initial bark removal, harvesters cut regrown cork every 6 to 10 years. Stripping the cork involves cutting two circular and one or more vertical cuts without damaging the inner bark. The cork worker uses a bevelled hatchet handle to remove the cork sheets. The cork is then boiled, scraped and cut into marketable sizes.

Cinnamon tree cultivation has spread from Sri Lanka to Indonesia, East Africa and the West Indies. An ancient tree management technique is still used in cinnamon cultivation (as well as willow and cascara tree cultivation). The technique is called coppicing, from the French word couper, meaning to cut. In neolithic times, humans discovered that when a tree is cut close to the ground, a mass of similar, straight branches would sprout from the root around the stump, and that these stems could be regenerated by regular cutting just above ground. The cinnamon tree can grow to 18 m but is maintained as 2-metre-high coppices. The main stem is cut at three years, and the resulting coppices are harvested every two to three years. After cutting and bundling the coppices, the cinnamon gatherers slit the bark sides with a sharp, curved knife. They then strip the bark off and after one to two days separate the outer and inner bark. The outer corky layer is scraped off with a broad, blunt knife and discarded. The inner bark (phloem) is cut into 1-metre lengths called quills; these are the familiar cinnamon sticks.

Bulk bark and ingredients

In the second major process, bark may also be removed from cut trees in large rotating containers called debarking drums. Bark, as a byproduct of lumber, is used as fuel, fibre, mulch or tannin. Tannin is among the most important bark products and is used to produce leather from animal skins and in food processing (see the chapter Leather, fur and footwear). Tannins are derived from a variety of tree barks around the world by open diffusion or percolation.

In addition to tannin, many barks are harvested for their ingredients, which include witch hazel and camphor. Witch hazel is a lotion extracted by steam distillation of twigs from the North American witch hazel tree. Similar processes are used in harvesting camphor from branches of the camphor laurel tree.

Tree fluids

The third major process includes the harvesting of resin and latex from the inner bark and oeloresins and syrup from the sapwood. Resin is found especially in the pine. It oozes out of bark wounds to protect the tree from infection. To commercially obtain resin, the worker must wound the tree by peeling off a thin layer of the bark or piercing it.

Most resins thicken and harden when exposed to the air, but some trees produce liquid resins or oleoresins, such as turpentine from conifers. Severe wounds are made into one side of the tree wood to harvest turpentine. The turpentine runs down the wound and is collected and hauled to storage. Turpentine is distilled into turpentine oil with a colophony or rosin residue.

Any milky sap exuded by plants is called latex, which in rubber trees is formed in the inner bark. Latex gatherers tap the rubber trees with spiral cuts around the trunk without damaging the inner bark. They catch the latex in a bowl (see the chapter Rubber industry). The latex is kept from hardening either through coagulation or with an ammonium hydroxide fixative. Acid wood smoke in the Amazon or formic acid is used to coagulate raw rubber. Crude rubber is then shipped for processing.

In the early spring in the cold climates of the United States, Canada, and Finland, a syrup is harvested from the sugar maple tree. After the sap starts to run, spouts are placed into drilled holes in the trunk through which sap runs either into buckets or through plastic piping for transport to storage tanks. The sap is boiled to 1/40th of its original volume to produce maple syrup. Reverse osmosis may be used to remove much of the water prior to evaporation. The concentrated syrup is cooled and bottled.

Hazards and Their Prevention

The hazards related to producing bark and sap for processing are natural exposures, injuries, pesticide exposures, allergies and dermatitis. Natural hazards include snake and insect bites and the potential for infection where vector-borne or water-borne diseases are endemic. Mosquito control is important on plantations, and pure water supply and sanitation is important at any tree farm, grove or plantation.

Much of the work with bark stripping, cutting and tapping involves the possibility of cuts, which should be promptly treated to prevent infection. Hazards exist in the manual cutting of trees, but mechanized methods of clearing as well as planting have reduced injury hazards. The use of heat for “smoking” rubber and evaporating oils from bark, resins and sap expose workers to burns. Hot maple syrup exposes workers to scalding injuries during boiling. Special hazards include working with draught animals or vehicles, tool-related injuries and the lifting of bark or containers. Bark stripping machines expose workers to potentially serious injury as well as to noise. Injury control techniques are needed, including safe work practices, personal protection and engineering controls.

Pesticide exposures, especially to the herbicide sodium arsenite on rubber plantations, are potentially hazardous. These exposures can be controlled by following manufacturer recommendations for storage, mixing and spraying.

Allergic proteins have been identified in natural rubber sap, which has been associated with latex allergy (Makinen-Kiljunen et al. 1992). Substances in pine resin and sap can cause allergic reactions in persons sensitive to balsam-of-Peru, colophony or turpentine. Resins, terpenes and oils may cause allergic contact dermatitis in workers handling unfinished wood. Dermal exposures to latex, sap and resin should be avoided through safe work practices and protective clothing.

The disease hypersensitivity pneumonitis is also known as “maple stripper’s lung”. It is caused by exposure to the spores of Cryptostroma corticate, a black mould that grows under the bark, during bark removal from stored maple. Progressive pneumonitis may also be associated with sequoia and cork oak woods. Controls include eliminating the sawing operation, wetting the material during debarking with a detergent and ventilation of the debarking area.

Tropical Tree and Palm Crops

Some text was revised from the articles “Date palms”, by D. Abed; “Raffia” and “Sisal”, by E. Arreguin Velez; “Copra”, by A.P. Bulengo; “Kapok”, by U. Egtasaeng; “Coconut cultivation”, by L.V.R. Fernando; “Bananas”, by Y. Ko; “Coir”, by P.V.C. Pinnagoda; and “Oil palms”, by G.O. Sofoluwe from the 3rd edition of this “Encyclopaedia”.

Although archaeological evidence is inconclusive, tropical forest trees transplanted to the village may have been the first domesticated agricultural crops. More than 200 fruit tree species have been identified in the humid tropics. Several of these trees and palms, such as the banana and coconut, are cultivated in smallholdings, cooperatives or plantations. While the date palm is completely domesticated, other species, such as the Brazil nut, are still harvested in the wild. More than 150 varieties of bananas and 2,500 palm species exist around the world, and they provide a broad range of products for human use. Sago palm wood feeds millions of people around the world. The coconut palm is used in more than 1,000 ways and the palmyra palm in more than 800 ways. About 400,000 people depend on the coconut for their entire livelihood. Several trees, fruits and palms of the tropical and semitropical zones of the world are listed in table 1, and table 2 shows selected commercial palms or palm types and their products.

Table 1. Commercial tropical and subtropical trees, fruits and palms

|

Categories |

Species |

|

Tropical and semitropical fruits (excluding citrus) |

Figs, banana, jelly palm, loquat, papaya, guava, mango, kiwis, date, cherimoya, white sapota, durian, breadfruit, Surinam cherry, lychee, olive, carambola, carob, chocolate, loquat, avocado, sapodilla, japoticaba, pomegranate, pineapple |

|

Semitropical citrus fruits |

Orange, grapefruit, lime, lemon, tangerine, tangelos, calamondins, kumquats, citrons |

|

Tropical nut trees |

Cashew, Brazil, almond, pine, and macadamia nuts |

|

Oil crops |

Oil palm, olive, coconut |

|

Insect feed |

Mulberry leaf (silkworm feed), decaying sago palm pith (grub feed) |

|

Fibre crops |

Kapok, sisal, hemp, coir (coconut husk), raffia palm, piassaba palm, palmyra palm, fishtail palm |

|

Starch |

Sago palm |

|

Vanilla bean |

Vanilla orchid |

|

Groups |

Products |

Uses |

|

Coconut |

Nut meat Copra (desiccated meat) Nut water Nut shells Coir (husk) Leaves Wood Flower nectar inflorescence |

Food, copra, animal feed Food, oil, oilsoap, candle, cooking oil, margarine, cosmetics, detergent, pai, coconut milk, cream, jam Fuel, charcoal, bowls, scoops, cups Mats, string, potting soil mix, brush, rope, cordage Thatching, weaving Building Palm honey Palm sugar, alcohol, arrack (palm spirits) |

|

Date |

Fruit Sap |

Dry, sweet and fine dates Date sugar |

|

African oil |

Fruit (palm pulp oil; similar to olive oil) Seeds (palm kernel oil) |

Cosmetics, margarine, dressing, fuel, lubricants Soap, glycerine |

|

Palmyra |

Leaves Petioles and leaf sheaths Truck Fruit and seeds Sap, roots |

Paper, shelter, weaving, fans, buckets, caps Carpets, rope, twine, brooms, brushes Timber, sago, cabbage Food, fruit pulp, starch, buttons Sugar, wine, alcohol, vinegar, sura (raw sap drink) Food, diuretic |

|

Sago (trunk pith of various species) |

Starch Insect feed |

Meals, gruels, puddings, bread, flour Food (grubs feeding on decayed sago pith) |

|

Cabbage (various species) |

Apical bud (upper trunk) |

Salads, canned palm hearts or palmito |

|

Raffia |

Leaves |

Plaiting, baskets work, tying material |

|

Sugar (various species) |

Palm sap |

Palm sugar (gur, jaggery) |

|

Wax |

Leaves |

Candles, lipsticks, shoe polish, car polish, floor wax |

|

Rattan cane |

Stems |

Furniture |

|

Betel nut |

Fruit (nut) |

Stimulant (betel chewing) |

Processes

The agriculture of tropical tree and palm growing includes propagation, cultivation, harvesting and post-harvesting processes.

Propagation of tropical trees and palms can be sexual or asexual. Sexual techniques are needed to produce fruit; pollination is critical. The date palm is doecious, and pollen from the male palm must be dispersed upon the female flowers. Pollination is done either by hand or mechanically. The manual process involves the workers climbing the tree by gripping the truck or using tall ladders to hand pollinate the female trees by placing small male clusters in the center of each female cluster. The mechanical process uses a powerful sprayer to carry the pollen over the female clusters. In addition to use for generating products, sexual techniques are used to produce seed, which is planted and cultivated into new plants. An example of an asexual technique is cutting shoots from mature plants for replanting.

Cultivation can be manual or mechanized. Banana cultivation is typically manual, but in flat terrain, mechanization with large tractors is used. Mechanical shovels may be used to dig drainage ditches in banana fields. Fertilizer is added monthly to bananas, and pesticides are applied with boom sprayers or from the air. The plants are supported with bamboo poles against storm damage. A banana plant bears fruit after two years.

Harvesting relies largely on manual labour, though some machinery is also used. Harvesters cut the banana bunches, called hands, from the tree with a knife attached to a long pole. The bunch is dropped onto a worker’s shoulder and a second worker attaches a nylon cord to the bunch, which is then attached to an overhead cable that moves the bunch to a tractor and trailer for transport. Tapping the coconut inflorescence for the juice entails the taper walking from tree to tree on strands of rope high above the ground. Workers climb to the tree tops to pluck the nuts manually or cut the nuts with a knife attached to long bamboo poles. In the Southwest Pacific area the nuts are allowed to fall naturally; then they are gathered. The date ripens in the fall and two or three crops are gathered, requiring climbing the tree or a ladder to the date clusters. An old system of machete harvesting of fruit bunches has been replaced by the use of a hook and pole. However, the machete is still used in harvesting many crops (e.g., sisal leaves).

Post-harvest operations vary between tree and palm and by the expected product. After harvesting, banana workers—typically women and youth—wash the bananas, wrap them in polyethylene and pack them in corrugated cardboard boxes for shipping. Sisal leaves are dried, bound and transported to the factory. Kapok fruit is field dried, and the resulting brittle fruit is broken open with a hammer or pipe. Kapok fibers are then ginned in the field to remove seeds by shaking or stirring, packed in jute sacks, batted in sacks to soften the fibers and baled. After harvest, dates are hydrated and artificially ripened. They are exposed to hot air (100 to 110 °C) to glaze the skin and semi-pasteurize them and then packaged.

The dried meaty endosperm of the coconut is marketed as copra, and the prepared husk of the coconut is marketed as coir. The fibrous nut husks are stripped off by striking and levering them against spikes firmly fixed into the ground. The nut, stripped of the husk, is split in half with an axe and dried either in the sun, kilns or hot-air dryers. After drying, the meat is separated from the hard woody shell. Copra is used to produce coconut oil, oil extraction residue called copra cake or poonac and desiccated food. The coir is retted (partially rotted) by soaking in water for three to four weeks. Workers remove the retted coir from the pits in waist-deep water and send it for decortication, bleaching and processing.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Hazards in tropical fruit and palm crop production include injuries, natural exposures, pesticide exposures and respiratory and dermatitis problems. Working at high elevations is required for much work with many tropical trees and palms. The popular apple banana grows to 5 m, kapok to 15 m, coconut palms to 20 to 30 m, evergreen date palm to 30 m, and the oil palm, 12 m. Falls represent one of the most serious hazards in tropical tree cultivation, and so do falling objects. Safety harnesses and head protection should be used, and workers should be trained in their use. Using dwarf varieties of the palms may help eliminate the tree falls. Falls from the kapok tree because of branches breaking and minor hand injuries during shell cracking are also hazards.

Workers can be injured during the transport on trucks or tractor-drawn trailers. Workers climbing palms receive cuts and abrasions of the hands due to contact with sharp date palm spines and oil palm fruit as well as spiny sisal leaves. Sprains from falling in ditches and holes are a problem. Severe wounds from the machete may be inflicted. Workers, typically women, who lift packed boxes of bananas are exposed to heavy weights. Tractors should have safety cabs. Workers should be trained in the safe handling of agricultural implements, machinery guarding and safe tractor operation. Puncture-resistant gloves should be worn, and arm protection and hooks should be used in harvesting the oil palm fruit. Mechanization of weeding and cultivation reduces sprains from falls in ditches and holes. Safe and proper work practices should be used, such as proper lifting, getting help when lifting to reduce individual loads and taking breaks.

Natural hazards include snakes—a problem during forest clearing and in newly established plantations—and insects as well as diseases. Health problems include malaria, ancylostomiasis, anaemia and enteric diseases. The retting operation exposes workers to parasites and skin infections. Mosquito control, sanitation and safe drinking water are important.

Pesticide poisoning is a hazard in tropical tree production, and pesticides are used in significant quantities in fruit groves. However, palms have few problems with pests, and those that are a problem are unique to specific parts of the life cycle and thus can be identified for specific control. Integrated pest management and, when applying pesticides, following the manufacturer’s instructions are important protective measures.

Medical evaluations have identified cases of bronchial asthma among date workers probably from pollen exposure. Also reported among date workers are chronic dry eczema and “nail disease” (onychia). Respiratory protection should be provided during the pollination process, and workers should wear hand protection and frequently wash their hands to protect their skin when working with the trees and dates.

Orchard Crops

Generally, farms where fruit trees grow in the temperate zones are called orchards; tropical trees are typically grown in plantation or village groves. Naturally occurring fruit trees have been bred and selected over the centuries to produce a diversity of cultivars. Temperate orchard crops include the apple, pear, peach, nectarine, plum, apricot, cherry, persimmon and prune. Nut crops grown in either temperate or semitropical climates include the pecan, almond, walnut, filbert, hazelnut, chestnut and pistachio. Semitropical orchard crops include the orange, grapefruit, tangerine, lime, lemon, figs, kiwis, tangelo, kumquat, calamondin (Panama orange), citron, Javanese pomelo and date.

Orchard Systems

The growing of fruit trees involves several processes. Orchardists may choose to propagate their own stock either by planting seed or asexually through one or more cutting, budding, grafting or tissue culture techniques. Orchardists plow or disk the soil for planting the tree stock, dig holes in the soil, plant the tree and add water and fertilizer.

Growing the tree requires fertilizing, weed control, irrigation and protecting the tree from spring frost. Fertilizer is applied aggressively during the early years of a tree’s growth. Components of fertilizers mixtures used include ammonium nitrate and suphate, elemental fertilizer (nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium), cottonseed meal, blood meal, fish meal, sterilized sewage sludge and urea formaldehyde (slow release). Weeds are controlled by mulching, tilling, mowing, hoeing and applying herbicides. Insecticides and fungicides are applied with sprayers, which are tractor-drawn in the larger operations. Several pests can damage the bark or eat the fruit, including squirrels, rabbits, raccoons, opossums, mice, rats and deer. Controls include netting, live traps, electric fences and guns, as well as visual or odorous deterrents.

Spring freezes can destroy flower blooms in hours. Overhead sprinklers are used to maintain a water-ice mixture so that the temperature does not drop below freezing. Special frost-guard chemicals may be applied with the water to control ice-nucleating bacteria, which can attack damaged tree tissue. Heaters also may be used in the orchard to prevent freezing, and they may be oil-fired in open areas or electric incandescent bulbs under a plastic film supported by plastic pipe frames.

Pruning tools can transmit disease, so they are soaked in a water-chlorine bleach solution or rubbing alcohol after pruning each tree. All limbs and trimmings are removed, shredded and composted. Limbs are trained, which requires the positioning of scaffolds between limbs, building trellises, pounding vertical stakes into the soil and tying limbs to these devises.

The honey-bee is the principal pollinator of fruit trees. Partial girdling—knife cuts into the bark on each side of the trunk—of the peach and pear tree can stimulate production. To avoid excess stunting, limb breakage and irregular bearing, orchardists thin the fruit either by hand or chemically. The insecticide carbaryl (Sevin), a photo inhibitor, is used for chemical thinning.

Manual fruit picking requires climbing ladders, reaching for the fruit or nuts, placing the fruit into containers and carrying the filled container down the ladder and to a collection area. Pecans are knocked from the trees with long poles and gathered manually or by a special machine that envelopes and shakes the tree trunk and catches and automatically funnels the pecans into a container. Trucks and trailers are commonly used in the field during harvest and for transport on public roads.

Tree Crop Hazards

Orchardists use a variety of agricultural chemicals, including fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides and fungicides. Pesticide exposures occur during application, from residues during various tasks, from pesticide drift, during mixing and loading and during harvesting. Employees may also be exposed to noise, diesel exhaust, solvents, fuels and oils. Malignant melanoma is elevated for orchardists as well, especially to the trunk, scalp and arms, presumably from sunlight (ultraviolet exposure). Handling some types of fruit, especially citrus, may cause allergies or other skin problems.

Rotary mowers are popular machines for cutting weeds. These mowers are attached to and powered by tractors. Riders on tractors can fall off and be seriously injured or killed by the mower, and debris can be thrown hundreds of metres and cause injury.

The construction of fences, trellises and vertical stakes in orchards may require the use of tractor-mounted post hole diggers or post drivers. Post hole diggers are tractor-powered augers that drill holes 15 to 30 cm in diameter. Post drivers are tractor-power impact drivers for pounding posts into the soil. Both of these machines are dangerous if not operated properly.

Dry fertilizer can cause skin burns and irritation of the mouth, nose and eyes. The spinning mechanism at the rear of a centrifugal broadcast spreader is also a source of injury. Spreaders are also cleaned with diesel fuel, which presents a fire hazard.

Fatalities among orchard workers may occur from motor vehicle crashes, tractor rollovers, farm machinery incidents and electrocutions from moving irrigation pipe or ladders that come into contact with overhead power lines. For orchard work, rollover protective structures (ROPs) are commonly removed from tractors because of their interference with tree limbs.

Manual handling of fruit and nuts in the picking and carrying operations places orchardists at

risk of sprain and strain injury. In addition, hand tools such as knives and shears are hazards for cuts in orchard work. Orchardists are also exposed to falling objects from the trees during harvesting and injury from falls from ladders.

Hazard Control

In the use of pesticides, the pest must be identified first so that the most effective control method and timing of control can be used. Safety procedures on the label should be followed, including the use of personal protective equipment. Heat stress is a hazard when wearing protective gear, so frequent rest breaks and plenty of drinking water are needed. Attention needs to be given to allowing enough reentry time to prevent hazardous exposures from pesticide residue, and pesticide drift from applications elsewhere in the orchard needs to be avoided. Good sanitary facilities are needed, and gloves may be useful to avoid skin disorders. In addition, table 1 shows several safety precautions in operating rotary mowers, post hole diggers, post drivers and fertilizer spreading.

Table 1. Safety precautions for rotary mowers, post hole diggers and post drivers

Rotary mowers (cutters)

- Avoid cutting over tree stumps, metal, and rocks, which can become projectiles thrown

from the mower.

- Keep people out of the work area to avoid being struck by flying objects.

- Maintain the chain guards around the mower to prevent projectiles from being

- thrown from the mower.

- Do not allow riders on the tractor to avoid a fall under the mower.

- Keep PTO shields in place.

- Disengage the PTO before starting the tractor.

- Use care when turning sharp corners and pulling drawn mowers so as not to

catch the mower on the tractor wheel, which can result in the mower being

thrown towards the operator.

- Use front wheel weights when attached to a mower by the three-point hitch so

as to keep the front wheels on the round to maintain steering control.

- Use wide-set tires if possible to add to tractor stability.

- Lower the mower to the ground before leaving it unattended.

Post hole diggers (tractor mounted augers)

- Shift the transmission into park or neutral before operation.

- Set tractor brakes before digging.

- Run the digger slowly to maintain control.

- Dig the hole in small steps.

- Never wear loose hair, clothing, or drawstrings when digging.

- Keep everyone clear of the auger and power shafts when digging.

- Stop the auger and lower it to the ground when not digging.

- Do not engage the power when unlodging an auger. Remove lodged augers

manually by turning it counter clockwise and then hydraulically lift the auger with the tractor.

Post drivers (tractor mounted, impact driver)

- Shut off the tractor engine and lower the hammer before lubrication or adjustment.

- Never place hands between the top of the post and the hammer.

- Do not exceed the recommended hammer stroke per minute.

- Use a guide to hold the post during driving in case the post breaks.

- Keep hands clear of posts that are about to be driven.

- Put all shields in place before operation.

- Wear safety glasses and hearing protection during operation.

Fertilizer spreading (mechanical)

- Stay clear of the rear of fertilizer spreaders.

- Do not unplug a spreader while it is operating.

- Work in well-ventilated areas away from fire ignition sources when cleaning

the spreaders with diesel fuel.

- Keep the dust off of skin, wear long sleeved shirts, and button collar when

handling dry fertilizer. Wash several times a day.

- Work with the wind blowing away from work.

- Tractor operators should drive crosswind to the spreader to avoid dust blowing onto them.

Where ROPs interfere with orchard work, foldable or telescoping ROPs should be installed. The operator should not be belted into the seat when operating without a deployed ROPs. As soon as overhead clearance permits, the ROPs should be deployed and the seat belt fastened.

To prevent falls, use of the top step of the ladder should be prohibited, the ladder rungs should have anti-slip surfaces and workers should be trained and oriented on proper ladder use at the beginning of their employment. Non-conductive ladders or ladders with insulators designed into them should be used to avoid possible electrical shock if they contact a power line.

Berries and Grapes

This article covers the injury and illness prevention methods against hazards commonly encountered in production of grapes (for fresh consumption, wine, juice or raisins) and berries, including brambles (i.e., raspberries), strawberries and bush berries (i.e., blueberries and cranberries).

Grapevines are stems that climb on supporting structures. Vines planted in commercial vineyards are usually started in spring from year-old rooted or grafted cuttings. They are typically planted 2 to 3.5 m apart. Each year, the vines must be dug over, fertilized, subdivided and pruned. The style of pruning varies in different parts of the world. In the system prevalent in the United States, all the shoots except the strongest ones on the vine are later pruned; the remaining shoots are cut back to 2 or 3 buds. The resulting plant develops a strong main stem which can stand alone, before it is allowed to bear fruit. During the expansion of the main stem, the vine is loosely tied to an upright support 1.8 m tall or higher. After the fruit-producing stage is reached, the vines are carefully pruned to control the number of buds.

Strawberries are planted in early spring, midsummer or later, depending on the latitude. The plants bear fruit in the spring of the following year. A variety called everbearing strawberries produces a second, smaller crop of fruit in the fall. Most strawberries are propagated naturally by means of runners that form about two months after the planting season. The fruit is found at ground level. Brambles such as raspberries are typically shrubs with prickly stems (canes) and edible fruits. The underground parts of brambles are perennial and the canes biennial; only second-year canes bear flowers and fruits. Brambles grow fruit at heights of 2 m or less. Like grapevines, berries require frequent pruning.

Growing practices differ for each fruit species, depending on the type of soil, climate and fertilizer it needs. Close control of insects and diseases is essential, often requiring frequent application of pesticides. Some modern growers have shifted toward biological controls and careful monitoring of pest populations, spraying chemicals only at the most effective times. Most grapes and berries are harvested by hand.

In a study of non-fatal injuries for the 10-year period 1981 through 1990 in California, the most common injury within this category of farms was sprains and strains, accounting for 42% of all injuries reported. Lacerations, fractures and contusions accounted for another 37% of injuries. The most common causes of injuries were being struck by an object (27%), overexertion (23%) and falls (19%) (AgSafe 1992). In a 1991 survey, Steinke (1991) found that 65% of injuries on farms identified as producing this category of crops in California were strains, sprains, lacerations, fractures and contusions. Parts of the body injured were fingers (17%), the back (15%), eyes (14%) and the hand or wrist (11%). Villarejo (1995) reported that there were 6,000 injury claims awarded per 100,000 full-time equivalents to workers in strawberry production in California in 1989. He also noted that most workers do not find employment throughout the year, so that the percentage of workers who suffer injuries could be several times higher than the 6% figure reported.

Musculoskeletal Problems

The major hazard associated with musculoskeletal injuries in these crops is rate of work. If the owner is working in the fields, she or he is typically working quickly to finish one task and move on to the next task. Hired labour is often paid by piece-rate, the practice of paying for work solely based upon what is accomplished (i.e., kilograms of berries harvested or number of grapevines pruned). This type of payment is often at odds with the extra time required to make sure fingers are out of the clipper before squeezing, or carefully walking to and from the edge of the field when exchanging filled baskets for empty ones during harvest. A high rate of work performance can lead to using poor postures, taking undue risks, and not following good safety practices and procedures.

Hand pruning of berries or vines requires the frequent squeezing of the hand to engage a clipper, or the frequent use of a knife. Hazards from the knife are obvious, as there is no solid surface against which to place the vine, shoot or stalk and frequent cuts to the fingers, hands, arms, legs and feet are likely to result. Pruning with a knife should be done only as a last resort.

Although a clipper is the preferred tool for pruning, either in the dormant season or while foliage is on the plants or vines, its use does have hazards. The major safety hazard is the threat of cuts from contact with the open blade while placing a vine or stalk in the jaws, or from inadvertent cutting of a finger while also cutting a vine or stalk. Sturdy leather or cloth gloves are good protection against both hazards and can also provide protection against contact dermatitis, allergies, insects, bees and cuts from a trellis.

The frequency and effort required for cutting determines the likelihood of development of cumulative-trauma injuries. Although injury reports do not currently show widespread injury, this is believed to be due to the frequent job rotation found on farms. The force required to operate a common clipper is in excess of recommended values, and the frequency of effort indicates the potential for cumulative-trauma disorders, according to accepted guidelines (Miles 1996).

To minimize likelihood of injury, clippers should be kept well lubricated and blades should be sharpened frequently. When large vines are encountered, as they are frequently in grapes, the size of the clipper should be increased accordingly, so as not to overload the wrist or the clipper itself. Lopping shears or pruning saws are often required for safe cutting of large vines or plants.

Lifting and carrying of loads is typically associated with harvesting of these crops. The berries or fruit are usually hand harvested and carried in some type of basket or carrier to the edge of the field, where they are deposited. Loads are often not heavy (10 kg or less), but the distance to be travelled is significant in many cases and over uneven terrain, which may also be wet or slippery. Workers should not run on the uneven terrain and should maintain solid footing at all times.

Harvesting of these crops is often done in awkward postures and at a rapid pace. Persons typically twist and bend, bend to the ground without bending the knees and move quickly between the bush or vine and the container. Containers are sometimes placed upon the ground and pushed or pulled along with the worker. Fruit and berries can be found anywhere from ground level to 2 m in height, depending upon the crop. Brambles are typically found at heights of 1 m or less, leading to almost continuous bending of the back during harvest. Strawberries are at ground level, but workers remain on their feet and bend down to harvest.

Grapes are also commonly cut to free them from the vine during hand harvest. This cutting motion is also very frequent (hundreds of times per hour) and requires sufficient force to cause concern regarding cumulative-trauma injuries if the harvest season were to last more then a few weeks.

Working with trellises or arbours is often involved in production of vines and berries. Installing or repairing arbours frequently involves doing work at heights above one’s head and stretching while exerting a force. Sustained effort of this type can lead to cumulative injuries. Each instance is an exposure to strain and sprain injury, particularly to the shoulders and arms, resulting from exerting significant force while working in an awkward posture. Training plants on trellises requires the exertion of substantial force, a force that is increased by the weight of the vines, foliage and fruit. This force is commonly exerted through the arms, shoulders and back, all of which are susceptible to both acute and long-term injury from such overexertion.

Pesticides and Fertilizers

Grapes and berries are subject to frequent pesticide applications for control of insects and disease pathogens. Applicators, mixers, loaders and anyone else in the field or assisting with the application should follow the precautions listed on the pesticide label or as required by local regulations. Applications in these crops can be particularly hazardous because of the nature of the deposit required for pest control. Frequently, all portions of the plant must be covered, including the undersides of the leaves and all surfaces of the fruit or berries. This often implies use of very small droplets and the use of air to promote canopy penetration and deposit of the pesticide. Thus many aerosols are produced, which can be hazardous through inhalation, ocular and dermal exposure routes.

Fungicides are frequently applied as dusts to grapes and many types of berries. The most common of these dusts is sulphur, which may be used in organic farming. Sulphur can be irritating to the applicator and to others in the field. It has also been known to reach air concentrations sufficient to cause explosions and fires. Care should be taken to avoid travelling through a cloud of sulphur dust with any possible ignition source, such as an engine, electric motor or other spark-producing device.

Many fields are fumigated with highly toxic materials before these crops are planted in order to reduce the population of such pests as nematodes, bacteria, fungi and viruses before they can attack the young plants. Fumigation usually involves injection of a gas or liquid into the soil and covering with a plastic sheet to prevent the pesticide from escaping too soon. Fumigation is a specialized practice and should be attempted only by those properly trained. Fumigated fields should be posted with warnings and should not be entered until the cover has been removed and the fumigant has dissipated.

Fertilizers may generate hazards during their application. Inhalation of dust, skin contact dermatitis and irritation of the lungs, throat and breathing passages may occur. A dust mask may be useful in reducing exposure to non-irritating levels.

Workers may be required to enter fields for culturing operations such as irrigation, pruning or harvest soon after pesticides have been applied. If this is sooner than the re-entry interval specified by the pesticide label or local regulations, protective clothing must be worn to protect against exposure. The minimum protection should be a long-sleeved shirt, long-legged pants, gloves, head covering, foot coverings and eye protection. More stringent protection, including a respirator, impermeable clothing and rubber boots may be required based upon the pesticide used, time since the application and regulations. Local pesticide authorities should be consulted to determine the proper level of protection.

Machine Exposures

The use of machinery in these crops is common for soil preparation, planting, weed cultivation and harvest. Many of these crops are grown on hillsides and uneven fields, increasing the chance for tractor and equipment rollovers. General safety rules of tractor and equipment operation to avoid rollovers should be followed, as should the policy of no riders on equipment unless additional personnel must be present for proper equipment operation and a platform is provided for their safety. More information on proper use of equipment can be found in the article “Mechanization” in this chapter and elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.

Many of these crops are also grown in uneven fields, such as on beds or ridges or in furrows. These features increase the danger when they become muddy, slippery or concealed by weeds or the plant canopy. Falling in front of equipment is a hazard, as is falling and straining or spraining a body part. Extra precautions should be taken particularly when fields are wet or at harvest, when discarded fruit may be underfoot.

Mechanical pruning of grapes is increasing around the world. Mechanical pruning typically involves rotating knives or fingers to gather vines and draw them past stationary knives. This equipment can be hazardous to anyone in the vicinity of the entry point for the cutters and should be used only by a properly trained operator.

Harvest operations typically use several machines at once, requiring coordination and cooperation of all equipment operators. Harvesting operations also, by their very nature, include crop gathering and removal, which frequently requires the use of vibrating rods or paddles, stripping fingers, fans, cutting or slicing operations and rakes, any of which are capable of causing great physical harm to persons who become entangled in them. Care should be taken to not place any person near the intake of such machines while they are running. Machine guards should always be kept in place and maintained. If guards must be removed for lubrication, adjustment or cleaning, they should be replaced before the machine is started again. Guards on an operating machine should never be opened or removed.

Other Hazards

Infections

One of the most common injuries suffered by workers in grapes and berries is a cut or puncture, either from thorns on the plant, tools or the trellis or support structure. Such open wounds are always subject to infection from the many bacteria, viruses or infectious agents present in fields. Such infections can cause serious complications, even loss of limb or life. All field workers should be protected with an up-to-date tetanus immunization. Cuts should be washed and cleaned, and antibacterial agent applied; any infections that develop should be treated by a physician immediately.

Insect bites and bee stings

Field workers tending and harvesting are at an increased risk of insect bites and bee stings. Placing hands and fingers into the plant canopy to select and grasp ripe fruit or berries increases the exposure to bees and insects that may be foraging or resting in the canopy. Some insects may be feeding on the ripe berries also, as could rodents and other vermin. The best protection is to wear long sleeves and gloves whenever working in the foliage.

Solar radiation

Heat stress

Exposure to excessive solar radiation and heat can easily lead to heat exhaustion, heat stroke or even death. Heat added to the human body through solar radiation, the effort of work and heat transfer from the environment must be removed from the body through sweat or sensible heat loss. When ambient temperatures are above 37 °C (i.e., normal body temperature), there can be no sensible heat loss, so the body must rely solely on perspiration for cooling.

Perspiration requires water. Anyone working in the sun or in a hot climate should drink plenty of fluids over the entire day. Water or sports drinks should be used, even before one feels thirsty. Alcohol and caffeine should be avoided, as they tend to act as diuretics and actually speed water loss and interfere with the body’s heat-regulating process. It is often recommended that persons drink 1 litre per hour of work in the sun or in hot climates. A sign of drinking insufficient fluids is the lack of the need to urinate.

Heat-related diseases can be life-threatening and require immediate attention. Persons suffering from heat exhaustion should be made to lie down in the shade and drink plenty of fluids. Anyone suffering from heat stroke is in grave danger and needs immediate attention. Medical assistance should be summoned immediately. If assistance is not available within a matter of minutes, one should attempt to cool the victim by immersing him or her in cool water. If the victim is unconscious, continued breathing should be assured through first aid. Do not give fluids by mouth.

Signs of heat-related diseases include excessive sweating, weakness in the limbs, disorientation, headaches, dizziness and, in extreme cases, loss of consciousness and also loss of the ability to sweat. The latter symptoms are immediately life-threatening, and action is required.

Working in vineyards and bush berry fields may increase the risk of heat-related illnesses. Air circulation is reduced between the rows, and there is the illusion of working partially in the shade. High relative humidity and cloud covers can also give one a false impression of the effects of the sun. It is necessary to drink plenty of fluids whenever working in fields.

Skin diseases

Long-term exposure to the sun can lead to premature ageing of the skin and increased likelihood of skin cancers. Persons exposed to the direct rays of the sun should wear clothing or sun-screen products to provide protection. At lower latitudes, even a few minutes of exposure to the sun can result in a severe sunburn, especially in those with fair complexions.

Skin cancers can begin on any part of the body, and suspected cancers should immediately be checked by a physician. Some of the frequent signs of skin cancers or pre-cancerous lesions are changes in a mole or birthmark, an irregular border, bleeding or a change in colour, often to a brown or gray tone. Those with a history of sun exposure should undergo annual skin cancer screenings.

Contact dermatitis and other allergies

Frequent and prolonged contact with plant excretions or plant pieces can result in sensitization and cases of contact allergies and dermatitis. Prevention through wearing long-sleeved shirts, long-legged pants and gloves whenever possible is the preferred course of action. Some creams can be used to provide a barrier to the transfer of irritants to the skin. If the skin cannot be protected from exposure to plants, washing immediately after the plant contact ends will minimize the effects. Cases of dermatitis with skin eruptions or which do not heal should be seen by a physician.

Vegetables and Melons

A wide variety of vegetables (herbaceous plants) is grown for edible leaves, stems, roots, fruits and seeds. Crops include leafy salad crops (e.g., lettuce and spinach), root crops (e.g., beets, carrots, turnips), cole crops (cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower) and many others grown for their fruit or seed (e.g., peas, beans, squashes, melons, tomatoes).

Since the 1940s, the nature of vegetable farming, particularly in North America and Europe, has changed dramatically. Previously, most fresh vegetables were grown close to population centres by garden or truck farmers and were available only during or shortly after harvest. The growth of supermarkets and the development of large food-processing companies created a demand for steady, year-round supplies of vegetables. At the same time, large-scale vegetable production on commercial farms became possible in areas far from major population centres because of rapidly expanding irrigation systems, improved insect sprays and weed control, and the development of sophisticated machinery for planting, spraying, harvesting and grading. Today, the main source of fresh vegetables in the United States is long-season areas, such as the states of California, Florida, Texas and Arizona, and Mexico. Southern Europe and North Africa are major vegetable sources for northern Europe. Many vegetables are also grown in greenhouses. Farmers’ markets selling local produce, however, remain the major outlet for vegetable growers throughout much of the world, particularly in Asia, Africa and South America.

Vegetable farming requires substantial skills and care to ensure production of high-quality vegetables that will sell. Vegetable farming operations include soil preparation, planting and growing crops, harvesting, processing and transportation. Weed and pest control and water management are crucial.

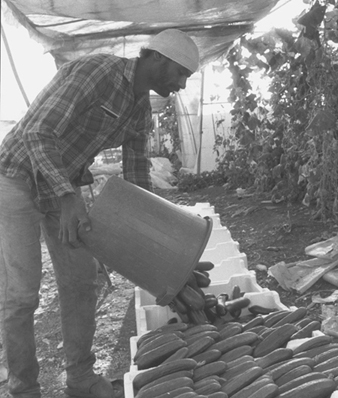

Vegetable and melon workers are exposed to many occupational hazards in their working environment, which include plants and their products, agrochemicals for controlling pests and oils and detergents for maintaining and repairing machinery. Manual or automatic work also forces the workers into uncomfortable positions (see figure 1). Musculoskeletal disorders such as low-back pain are important health problems in these workers. Agricultural tools and machines used with vegetables and melons give rise to high risks for traumatic injuries and various health impairments similar to those seen in other agricultural work. In addition, outdoor growers are exposed to solar radiation and heat, whereas exposure to pollens, endotoxins and fungi should be taken into account among greenhouse farmers. Therefore, a wide variety of work-related disorders can be found in those populations.

Figure 1. Manual labour on a vegetable farm near Assam, Jordan

Food allergies to vegetables and melons are well known. They are mostly provoked by vegetable allergens and can cause an immediate reaction. Clinically, mucocutaneous and respiratory symptoms appear in most patients. Occupational allergy among vegetable workers differs from food allergy in several ways. Occupational allergens are diverse, including those of vegetable origin, chemicals and biological derivatives. Artichoke, brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrot, celery, chicory, chive, endive, garlic, horseradish, leek, lettuce, okra, onion, parsley and parsnip have been reported to contain vegetable allergens and to sensitize vegetable workers. Occupational allergies to melon allergens, however, are seldom reported. Only a few allergens from vegetables and melons have been isolated and identified because of the difficulty and complexity of the laboratory techniques required. Most allergens, especially those of vegetable origin, are fat soluble, but a few are water soluble. The ability to sensitize also varies depending on botanical factors: The allergens may be sequestered in resin canals and released only when the vegetables are bruised. However, in other cases they may be readily released by fragile grandular hairs, or be excreted onto the leaf, coat the pollens or be widely disseminated by the action of wind on trichomes (hair-like growths on the plants).

Clinically, the most common occupational allergic diseases reported in the vegetable workers are allergic dermatitis, asthma and rhinitis. Extrinsic allergic alveolitis, allergic photodermatitis and allergic urticaria (hives) can be seen in some cases. It should be emphasized that vegetables, melons, fruits and pollens have some allergens in common or cross-reacting allergens. This implies that atopic persons and individuals with an allergy to one of those may become more susceptible than others in the development of occupational allergies. To screen and diagnose these occupational allergies, a number of immune tests are currently available. In general, the prick test, intradermal test, measurement of allergen-specific IgE antibody and in vivo allergen challenge test are used for immediate allergies, whereas the patch test can be chosen for delayed-type allergy. The allergen-specific lymphocyte proliferation test and cytokine production are helpful in diagnosing both types of allergy. These tests can be performed using native vegetables, their extracts and released chemicals.

Dermatoses such as pachylosis, hyperkeratosis, nail injury chromatosis and dermatitis are observed in vegetable workers. In particular, contact dermatitis, both irritant and allergic, occurs more frequently. Irritant dermatitis is caused by chemical and/or physical factors. Vegetable parts such as thrichomes, spicules, coarse hairs, raphides and spines are responsible for most of this irritation. On the other hand, allergic dermatitis is classified into immediate and delayed types on the basis of their immunopathogenesis. The former is mediated through humoural immune responses, whereas the later is mediated through cellular immune responses.