5. Mental Health

Chapter Editors: Joseph J. Hurrell, Lawrence R. Murphy, Steven L. Sauter and Lennart Levi

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Work and Mental Health

Irene L.D. Houtman and Michiel A.J. Kompier

Work-related Psychosis

Craig Stenberg, Judith Holder and Krishna Tallur

Mood and Affect

Depression

Jay Lasser and Jeffrey P. Kahn

Work-related Anxiety

Randal D. Beaton

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and its Relationship to Occupational Health and Injury Prevention

Mark Braverman

Stress and Burnout and their Implication in the Work Environment

Herbert J. Freudenberger

Cognitive Disorders

Catherine A. Heaney

Karoshi: Death from Overwork

Takashi Haratani

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Schematic overview of management strategies & examples

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Children categories

Depression

Depression is an enormously important topic in the area of workplace mental health, not only in terms of the impact depression can have on the workplace, but also the role the workplace can play as an aetiological agent of the disorder.

In a 1990 study, Greenberg et al. (1993a) estimated that the economic burden of depression in the United States that year was approximately US$ 43.7 billion. Of that total, 28% was attributable to direct costs of medical care, but 55% was derived from a combination of absenteeism and decreased productivity while at work. In another paper, the same authors (1993b) note:

“two distinguishing features of depression are that it is highly treatable and not widely recognized. The NIMH has noted that between 80% and 90% of individuals suffering from a major depressive disorder can be treated successfully, but that only one in three with the illness ever seeks treatment.… Unlike some other diseases, a very large share of the total costs of depression falls on employers. This suggests that employers as a group may have a particular incentive to invest in programs that could reduce the costs associated with this illness.”

Manifestations

Everyone feels sad or “depressed” from time to time, but a major depressive episode, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994), requires that several criteria be met. A full description of these criteria is beyond the scope of this article, but portions of criterion A, which describes the symptoms, can give one a sense of what a true major depression looks like:

A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is number 1 or 2.

- depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day

- markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day

- significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain, or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day

- insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

- psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day

- fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

- feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day

- diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness nearly every day

- recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation, with or without a plan, or a suicide attempt.

Besides giving one an idea of the discomfort suffered by a person with depression, a review of these criteria also shows the many ways depression can impact negatively on the workplace. It is also important to note the wide variation of symptoms. One depressed person may present barely able to move to get out of bed, while others may be so anxious they can hardly sit still and describe themselves as crawling out of their skin or losing their mind. Sometimes multiple physical aches and pains without medical explanation may be a hint of depression.

Prevalence

The following passage from Mental Health in the Workplace (Kahn 1993) describes the pervasiveness (and increase) of depression in the workplace:

“Depression … is one of the most common mental health problems in the workplace. Recent research … suggests that in industrialized countries the incidence of depression has increased with each decade since 1910, and the age at which someone is likely to become depressed has dropped with every generation born after 1940. Depressive illnesses are common and serious, taking a tremendous toll on both workers and workplace. Two out of ten workers can expect a depression during their lifetime, and women are one and a half times more likely than men to become depressed. One out of ten workers will develop a clinical depression serious enough to require time off from work.”

Thus, in addition to the qualitative aspects of depression, the quantitative/epidemiological aspects of the disease make it a major concern in the workplace.

Related Illnesses

Major depressive disorder is only one of a number of closely related illnesses, all under the category of “mood disorders”. The most well known of these is bipolar (or “manic-depressive”) illness, in which the patient has alternating periods of depression and mania, which includes a feeling of euphoria, a decreased need for sleep, excessive energy and rapid speech, and can progress to irritability and paranoia.

There are several different versions of bipolar disorder, depending on the frequency and severity of the depressive and manic episodes, the presence or absence of psychotic features (delusions, hallucinations) and so on. Similarly, there are several different variations on the theme of depression, depending on severity, presence or absence of psychosis, and types of symptom most prominent. Again, it is beyond the scope of this article to delineate all of these, but the reader is again referred to DSM IV for a complete listing of all the different forms of mood disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of major depression involves three major areas: other medical disorders, other psychiatric disorders and medication-induced symptoms.

Just as important as the fact that many patients with depression first present to their general practitioners with physical complaints is the fact that many patients who initially present to a mental health clinician with depressive complaints may have an undiagnosed medical illness causing the symptoms. Some of the most common illnesses causing depressive symptoms are endocrine (hormonal), such as hypothyroidism, adrenal problems or changes related to pregnancy or the menstrual cycle. Particularly in older patients, neurological diseases, such as dementia, strokes or Parkinson’s disease, become more prominent in the differential diagnosis. Other illnesses that can present with depressive symptoms are mononucleosis, AIDS, chronic fatigue syndrome and some cancers and joint diseases.

Psychiatrically, the disorders which share many common features with depression are the anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder), schizophrenia and drug and alcohol abuse. The list of medications that can cause depressive symptoms is quite lengthy, and includes pain medications, some antibiotics, many anti-hypertensives and cardiac drugs, and steroids and hormonal agents.

For further detail on all three areas of the differential diagnosis of depression, the reader is referred to Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry (1994), or the more detailed Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (Kaplan and Sadock 1995).

Workplace Aetiologies

Much can be found elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia regarding workplace stress, but what is important in this article is the manner in which certain aspects of stress can lead to depression. There are many schools of thought regarding the aetiology of depression, including biological, genetic and psychosocial. It is in the psychosocial realm that many factors relating to the workplace can be found.

Issues of loss or threatened loss can lead to depression and, in today’s climate of downsizing, mergers and shifting job descriptions, are common problems in the work environment. Another result of frequently changing job duties and the constant introduction of new technologies is to leave workers feeling incompetent or inadequate. According to psychodynamic theory, as the gap between one’s current self image and “ideal self” widens, depression ensues.

An animal experimental model known as “learned helplessness” can also be used to explain the ideological link between stressful workplace environments and depression. In these experiments, animals were exposed to electric shocks from which they could not escape. As they learned that none of the actions they took had any effect on their eventual fate, they displayed increasingly passive and depressive behaviours. It is not difficult to extrapolate this model to today’s workplace, where so many feel a sharply decreasing amount of control over both their day-to-day activities and long-range plans.

Treatment

In light of the aetiological link of the workplace to depression described above, a useful way of looking at the treatment of depression in the workplace is the primary, secondary, tertiary model of prevention. Primary prevention, or trying to eliminate the root cause of the problem, entails making fundamental organizational changes to ameliorate some of the stressors described above. Secondary prevention, or trying to “immunize” the individual from contracting the illness, would include such interventions as stress management training and lifestyle changes. Tertiary prevention, or helping to return the individual to health, involves both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological treatment.

There is an increasing array of psychotherapeutic approaches available to the clinician today. The psychodynamic therapies look at the patient’s struggles and conflicts in a loosely structured format that allows explorations of whatever material may come up in a session, however tangential it may initially appear. Some modifications of this model, with boundaries set in terms of number of sessions or breadth of focus, have been made to create many of the newer forms of brief therapy. Interpersonal therapy focuses more exclusively on the patterns of the patient’s relationships with others. An increasingly popular form of therapy is cognitive therapy, which is driven by the precept, “What you think is how you feel”. Here, in a very structured format, the patient’s “automatic thoughts” in response to certain situations are examined, questioned and then modified to produce a less maladaptive emotional response.

As rapidly as the psychotherapies have developed, the psychopharmacological armamentarium has probably grown even faster. In the few decades before the 1990s, the most common medications used to treat depression were the tricyclics (imipramine, amitriptyline and nortriptyline are examples) and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Nardil, Marplan and Parnate). These medications act on neurotransmitter systems thought to be involved with depression, but also affect many other receptors, resulting in a number of side effects. In the early 1990s, several new medications (fluoxetine, sertraline, Paxil, Effexor, fluvoxamine and nefazodone) were introduced. These medications have enjoyed rapid growth because they are “cleaner” (bind more specifically to depression-related neurotransmitter sites) and can thus effectively treat depression while causing much fewer side effects.

Summary

Depression is extremely important in the world of workplace mental health, both because of depression’s impact on the workplace, and the workplace’s impact on depression. It is a highly prevalent disease, and very treatable; but unfortunately frequently goes undetected and untreated, with serious consequences for both the individual and the employer. Thus, increased detection and treatment of depression can help lessen individual suffering and organizational losses.

Work-Related Anxiety

Anxiety disorders as well as subclinical fear, worry and apprehension, and associated stress-related disorders such as insomnia, appear to be pervasive and increasingly prevalent in workplaces in the 1990s—so much so, in fact, that the Wall Street Journal has referred to the 1990s as the work-related “Age of Angst” (Zachary and Ortega 1993). Corporate downsizing, threats to existing benefits, lay-offs, rumours of impending lay-offs, global competition, skill obsolescence and “de-skilling”, re-structuring, re-engineering, acquisitions, mergers and similar sources of organizational turmoil have all been recent trends that have eroded workers’ sense of job security and have contributed to palpable, but difficult to precisely measure, “work-related anxiety” (Buono and Bowditch 1989). Although there appear to be some individual differences and situational moderator variables, Kuhnert and Vance (1992) reported that both blue-collar and white-collar manufacturing employees who reported more “job insecurity” indicated significantly more anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms on a psychiatric checklist. For much of the 1980s and accelerating into the 1990s, the transitional organizational landscape of the US marketplace (or “permanent whitewater”, as it has been described) has undoubtedly contributed to this epidemic of work-related stress disorders, including, for example, anxiety disorders (Jeffreys 1995; Northwestern National Life 1991).

The problems of occupational stress and work-related psychological disorders appear to be global in nature, but there is a dearth of statistics outside of the United States documenting their nature and extent (Cooper and Payne 1992). The international data that are available, mostly from European countries, seem to confirm similar adverse mental health effects of job insecurity and high-strain employment on workers as those seen in US workers (Karasek and Theorell 1990). However, because of the very real stigma associated with mental disorders in most other countries and cultures, many, if not most, psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, related to work (outside of the United States) go unreported, undetected and untreated (Cooper and Payne 1992). In some cultures, these psychological disorders are somatized and manifested as “more acceptable” physical symptoms (Katon, Kleinman and Rosen 1982). A study of Japanese government workers has identified occupational stressors such as workload and role conflict as significant correlates of mental health in these Japanese workers (Mishima et al. 1995). Further studies of this kind are needed to document the impact of psychosocial job stressors on workers’ mental health in Asia, as well as in the developing and post-Communist countries.

Definition and Diagnosis of Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are evidently among the most prevalent of mental health problems afflicting, at any one time, perhaps 7 to 15% of the US adult population (Robins et al. 1981). Anxiety disorders are a family of mental health conditions which include agoraphobia (or, loosely, “houseboundness”), phobias (irrational fears), obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic attacks and generalized anxiety. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM IV), symptoms of a generalized anxiety disorder include feelings of “restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge”, fatigue, difficulties with concentration, excess muscle tension and disturbed sleep (American Psychiatric Association 1994). An obsessive-compulsive disorder is defined as either persistent thoughts or repetitive behaviours that are excessive/unreasonable, cause marked distress, are time consuming and can interfere with a person’s functioning. Also, according to DSM IV, panic attacks, defined as brief periods of intense fear or discomfort, are not actually disorders per se but may occur in conjunction with other anxiety disorders. Technically, the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder can be made only by a trained mental health professional using accepted diagnostic criteria.

Occupational Risk Factors for Anxiety Disorders

There is a paucity of data pertaining to the incidence and prevalence of anxiety disorders in the workplace. Furthermore, since the aetiology of most anxiety disorders is multifactorial, we cannot rule out the contribution of individual genetic, developmental and non-work factors in the genesis of anxiety conditions. It seems likely that both work-related organizational and such individual risk factors interact, and that this interaction determines the onset, progression and course of anxiety disorders.

The term job-related anxiety implies that there are work conditions, tasks and demands, and/or related occupational stressors that are associated with the onset of acute and/or chronic states of anxiety or manifestations of anxiety. These factors may include an overwhelming workload, the pace of work, deadlines and a perceived lack of personal control. The demand-control model predicts that workers in occupations which offer little personal control and expose employees to high levels of psychological demand would be at risk of adverse health outcomes, including anxiety disorders (Karasek and Theorell 1990). A study of pill consumption (mostly tranquilizers) reported for Swedish male employees in high-strain occupations supported this prediction (Karasek 1979). Certainly, the evidence for an increased prevalence of depression in certain high-strain occupations in the United States is now compelling (Eaton et al. 1990). More recent epidemiological studies, in addition to theoretical and biochemical models of anxiety and depression, have linked these disorders not only by identifying their co-morbidity (40 to 60%), but also in terms of more fundamental commonalities (Ballenger 1993). Hence, the Encyclopaedia chapter on job factors associated with depression may provide pertinent clues to occupational and individual risk factors also associated with anxiety disorders. In addition to risk factors associated with high-strain work, a number of other workplace variables contributing to employee psychological distress, including an increased prevalence of anxiety disorders, have been identified and are briefly summarized below.

Individuals employed in dangerous lines of work, such as law enforcement and firefighting, characterized by the probability that a worker will be exposed to a hazardous agent or injurious activity, would also seem to be at risk of heightened and more prevalent states of psychological distress, including anxiety. However, there is some evidence that individual workers in such dangerous occupations who view their work as “exhilarating” (as opposed to dangerous) may cope better in terms of their emotional responses to work (McIntosh 1995). Nevertheless, an analysis of stress symptomatology in a large group of professional firefighters and paramedics identified a central feature of perceived apprehension or dread. This “anxiety stress pathway” included subjective reports of “being keyed up and jittery” and “being uneasy and apprehensive.” These and similar anxiety-related complaints were significantly more prevalent and frequent in the firefighter/paramedic group relative to a male community comparison sample (Beaton et al. 1995).

Another worker population evidently at risk of experiencing high, and at times debilitating, levels of anxiety are professional musicians. Professional musicians and their work are exposed to intense scrutiny by their supervisors; they must perform before the public and must cope with performance and pre-performance anxiety or “stage fright”; and they are expected (by others as well as by themselves) to produce “note-perfect performances” (Sternbach 1995). Other occupational groups, such as theatrical performers and even teachers who give public performances, may have acute and chronic anxiety symptoms related to their work, but very little data on the actual prevalence or significance of such occupational anxiety disorders have been collected.

Another class of work-related anxiety for which we have little data is “computer phobics”, people who have responded anxiously to the advent of computing technology (Stiles 1994). Even though each generation of computer software is arguably more “user-friendly”, many workers are uneasy, while other workers are literally panicked by challenges of “techno-stress”. Some fear personal and professional failure associated with their inability to acquire the necessary skills to cope with each successive generation of technology. Finally, there is evidence that employees subjected to electronic performance monitoring perceive their jobs as more stressing and report more psychological symptoms, including anxiety, than workers not so monitored (Smith et al. 1992).

Interaction of Individual and Occupational Risk Factors for Anxiety

It is likely that individual risk factors interact with and may potentiate the above-cited organizational risk factors at the onset, progression and course of anxiety disorders. For example, an individual employee with a “Type A personality” may be more prone to anxiety and other mental health problems in high-strain occupational settings (Shima et al. 1995). To offer a more specific example, an overly responsible paramedic with a “rescue personality” may be more on edge and hypervigilant while on duty then another paramedic with a more philosophical work attitude: “You can’t save them all” (Mitchell and Bray 1990). Individual worker personality variables may also serve to potentially buffer attendant occupational risk factors. For instance, Kobasa, Maddi and Kahn (1982) reported that corporate managers with “hardy personalities” seem better able to cope with work-related stressors in terms of health outcomes. Thus, individual worker variables need to be considered and evaluated within the context of the particular occupational demands to predict their likely interactive impact on a given employee’s mental health.

Prevention and Remediation ofWork-related Anxiety

Many of the US and global workplace trends cited at the beginning of this article seem likely to persist into the foreseeable future. These workplace trends will adversely impact workers’ psychological and physical health. Psychological job enhancement, in terms of interventions and workplace redesign, may deter and prevent some of these adverse effects. Consistent with the demand-control model, workers’ well-being can be improved by increasing their decision latitude by, for example, designing and implementing a more horizontal organizational structure (Karasek and Theorell 1990). Many of the recommendations made by NIOSH researchers, such as improving workers’ sense of job security and decreasing work role ambiguity, if implemented, would also likely reduce job strain and work-related psychological disorders considerably, including anxiety disorders (Sauter, Murphy and Hurrell 1992).

In addition to organizational policy changes, the individual employee in the modern workplace also has a personal responsibility to manage his or her own stress and anxiety. Some common and effective coping strategies employed by US workers include separating work and non-work activities, getting sufficient rest and exercise, and pacing oneself at work (unless, of course, the job is machine paced). Other helpful cognitive-behavioural alternatives in self-managing and preventing anxiety disorders include deep-breathing techniques, biofeedback-aided relaxation training, and meditation (Rosch and Pelletier 1987). In certain cases medications may be necessary to treat a severe anxiety disorder. These medications, including antidepressants and other anxiolytic agents, are generally available only by prescription.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and its Relation to Occupational Health and Injury Prevention

Beyond the broad concept of stress and its relationship to general health issues, there has been little attention to the role of psychiatric diagnosis in the prevention and treatment of the mental health consequences of work-related injuries. Most of the work on job stress has been concerned with the effects of exposure to stressful conditions over time, rather than to problems associated with a specific event such as a traumatic or life-threatening injury or the witnessing of an industrial accident or act of violence. At the same time, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a condition which has received considerable credibility and interest since the mid-1980s, is being more widely applied in contexts outside of cases involving war trauma and victims of crime. With respect to the workplace, PTSD has begun to appear as the medical diagnosis in cases of occupational injury and as the emotional outcome of exposure to traumatic situations occurring in the workplace. It is often the subject of controversy and some confusion with respect to its relationship to work conditions and the responsibility of the employer when claims of psychological injury are made. The occupational health practitioner is called upon increasingly to advise on company policy in the handling of these exposures and injury claims, and to render medical opinions with respect to the diagnosis, treatment and ultimate job status of these employees. Familiarity with PTSD and its related conditions is therefore increasingly important for the occupational health practitioner.

The following topics will be reviewed in this article:

- differential diagnosis of PTSD with other conditions such as primary depression and anxiety disorders

- relationship of PTSD to stress-related somatic complaints

- prevention of post-traumatic stress reactions in survivors and witnesses of psychologically traumatic events occurring in the workplace

- prevention and treatment of complications of work injury related to post-traumatic stress.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder affects people who have been exposed to traumatizing events or conditions. It is characterized by symptoms of numbing, psychological and social withdrawal, difficulties controlling emotion, especially anger, and intrusive recollection and reliving of experiences of the traumatic event. By definition, a traumatizing event is one that is outside the normal range of everyday life events and is experienced as overwhelming by the individual. A traumatic event usually involves a threat to one’s own life or to someone close, or the witnessing of an actual death or serious injury, especially when this occurs suddenly or violently.

The psychiatric antecedents of our current concept of PTSD go back to the descriptions of “battle fatigue” and “shell shock” during and after the World Wars. However, the causes, symptoms, course and effective treatment of this often debilitating condition were still poorly understood when tens of thousands of Vietnam-era combat veterans began to appear in the US Veterans Administration Hospitals, offices of family doctors, jails and homeless shelters in the 1970s. Due in large part to the organized effort of veterans’ groups, in collaboration with the American Psychiatric Association, PTSD was first identified and described in 1980 in the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III) (American Psychiatric Association 1980). The condition is now known to affect a wide range of trauma victims, including survivors of civilian disasters, victims of crime, torture and terrorism, and survivors of childhood and domestic abuse. Although changes in the classification of the disorder are reflected in the current diagnostic manual (DSM IV), the diagnostic criteria and symptoms remain essentially unchanged (American Psychiatric Association 1994).

Diagnostic Criteria for Post-TraumaticStress Disorder

A. The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following were present:

- The person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others.

- The person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness or horror.

B. The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in one (or more) of the following ways:

- Recurrent and intrusive distressing recollections of the event, including images, thoughts or perceptions.

- Recurrent distressing dreams of the event.

- Acting or feeling as if the traumatic event were recurring.

- Intense psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

- Physiological reactivity on exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

- Efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings or conversations associated with the trauma.

- Efforts to avoid activities, places or people that arouse recollections of the trauma.

- Inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma.

- Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities.

- Feeling of detachment or estrangement from others.

- Restricted range of affect (e.g., unable to have loving feelings).

- Sense of a foreshortened future (e.g., does not expect to have a career, marriage, children or a normal life span).

D. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal (not present before the trauma), as indicated by two (or more) of the following:

- Difficulty falling or staying asleep.

- Irritability or outbursts of anger.

- Difficulty concentrating.

- Hypervigilance.

- Exaggerated startle response.

E. Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in criteria B, C and D) is more than 1 month.

F. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning.

Specify if:

Acute: if duration of symptoms is less than 3 months

Chronic: if duration of symptoms is 3 months or more.

Specify if:

With Delayed Onset: if onset of symptoms is at least 6 months after the stressor.

Psychological stress has achieved increasing recognition as an outcome of work-related hazards. The link between work hazards and post-traumatic stress was first established in the 1970s with the discovery of high incident rates of PTSD in workers in law enforcement, emergency medical, rescue and firefighting. Specific interventions have been developed to prevent PTSD in workers exposed to job-related traumatic stressors such as mutilating injury, death and use of deadly force. These interventions emphasize providing exposed workers with education about normal traumatic stress reactions, and the opportunity to actively surface their feelings and reactions with their peers. These techniques have become well established in these occupations in the United States, Australia and many European nations. Job-related traumatic stress, however, is not limited to workers in these high-risk industries. Many of the principles of preventive intervention developed for these occupations can be applied to programmes to reduce or prevent traumatic stress reactions in the general workforce.

Issues in Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis

The key to the differential diagnosis of PTSD and traumatic-stress-related conditions is the presence of a traumatic stressor. Although the stressor event must conform to criterion A—that is, be an event or situation that is outside of the normal range of experience—individuals respond in various ways to similar events. An event that precipitates a clinical stress reaction in one person may not affect another significantly. Therefore, the absence of symptoms in other similarly exposed workers should not cause the practitioner to discount the possibility of a true post-trauma reaction in a particular worker. Individual vulnerability to PTSD has as much to do with the emotional and cognitive impact of an experience on the victim as it does to the intensity of the stressor itself. A prime vulnerability factor is a history of psychological trauma due to a previous traumatic exposure or significant personal loss of some kind. When a symptom picture suggestive of PTSD is presented, it is important to establish whether an event that may satisfy the criterion for a trauma has occurred. This is particularly important because the victim himself may not make the connection between his symptoms and the traumatic event. This failure to connect the symptom with the cause follows the common “numbing” reaction, which may cause forgetting or dissociation of the event, and because it is not unusual for symptom appearance to be delayed for weeks or months. Chronic and often severe depression, anxiety and somatic conditions are often the result of a failure to diagnose and treat. Thus, early diagnosis is particularly important because of the often hidden nature of the condition, even to the sufferer him- or herself, and because of the implications for treatment.

Treatment

Although the depression and anxiety symptoms of PTSD may respond to usual therapies such as pharmacology, effective treatment is different from those usually recommended for these conditions. PTSD may be the most preventable of all psychiatric conditions and, in the occupational health sphere, perhaps the most preventable of all work-related injuries. Because its occurrence is linked so directly to a specific stressor event, treatment can focus on prevention. If proper preventive education and counselling are provided soon after the traumatic exposure, subsequent stress reactions can be minimized or prevented altogether. Whether the intervention is preventive or therapeutic depends largely on timing, but the methodology is essentially similar. The first step in successful treatment or preventive intervention is allowing the victim to establish the connection between the stressor and his or her symptoms. This identification and “normalization” of what are typically frightening and confusing reactions is very important for reduction or prevention of symptoms. Once the normalization of the stress response has been accomplished, treatment addresses the controlled processing of the emotional and cognitive impact of the experience.

PTSD or conditions related to traumatic stress result from the sealing off of unacceptable or unacceptably intense emotional and cognitive reactions to traumatic stressors. It is generally considered that the stress syndrome can be prevented by providing the opportunity for controlled processing of the reactions to the trauma before the sealing off of the trauma occurs. Thus, prevention through timely and skilled intervention is the keystone for the treatment of PTSD. These treatment principles may depart from the traditional psychiatric approach to many conditions. Therefore, it is important that employees at risk of post-traumatic stress reactions be treated by mental health professionals with specialized training and experience in treating trauma-related conditions. The length of treatment is variable. It will depend on the timing of the intervention, the severity of the stressor, symptom severity and the possibility that a traumatic exposure may precipitate an emotional crisis linked to earlier or related experiences. A further issue in treatment concerns the importance of group treatment modalities. Victims of trauma can achieve enormous benefit from the support of others who have shared the same or similar traumatic stress experience. This is of particular importance in the workplace context, when groups of co-workers or entire work organizations are affected by a tragic accident, act of violence or traumatic loss.

Prevention of Post-Traumatic Stress Reactionsafter Incidents of Workplace Trauma

A range of events or situations occurring in the workplace may put workers at risk of post-traumatic stress reactions. These include violence or threat of violence, including suicide, inter-employee violence and crime, such as armed robbery; fatal or severe injury; and sudden death or medical crisis, such as heart attack. Unless properly managed, these situations can cause a range of negative outcomes, including post-traumatic stress reactions that may reach clinical levels, and other stress-related effects that will affect health and work performance, including avoidance of the workplace, concentration difficulties, mood disturbances, social withdrawal, substance abuse and family problems. These problems can affect not only line employees but management staff as well. Managers are at particular risk because of conflicts between their operational responsibilities, their feelings of personal responsibility for the employees in their charge and their own sense of shock and grief. In the absence of clear company policies and prompt assistance from health personnel to deal with the aftermath of the trauma, managers at all levels may suffer from feelings of helplessness that compound their own traumatic stress reactions.

Traumatic events in the workplace require a definite response from upper management in close collaboration with health, safety, security, communications and other functions. A crisis response plan fulfils three primary goals:

- prevention of post-traumatic stress reactions by reaching affected individuals and groups before they have a chance to seal over

- communication of crisis-related information in order to contain fears and control rumours

- fostering of confidence that management is in control of the crisis and demonstrating concern for employees’ welfare.

The methodology for the implementation of such a plan has been fully described elsewhere (Braverman 1992a,b; 1993b). It emphasizes adequate communication between management and employees, assembling of groups of affected employees and prompt preventive counselling of those at highest risk for post-traumatic stress because of their levels of exposure or individual vulnerability factors.

Managers and company health personnel must function as a team to be sensitive for signs of continued or delayed trauma-related stress in the weeks and months after the traumatic event. These can be difficult to identify for manager and health professional alike, because post-traumatic stress reactions are often delayed, and they can masquerade as other problems. For a supervisor or for the nurse or counsellor who becomes involved, any signs of emotional stress, such as irritability, withdrawal or a drop in productivity, may signal a reaction to a traumatic stressor. Any change in behaviour, including increased absenteeism, or even a marked increase in work hours (“workaholism”) can be a signal. Indications of drug or alcohol abuse or change in moods should be explored as possibly linked to post-traumatic stress. A crisis response plan should include training for managers and health professionals to be alert for these signs so that intervention can be rendered at the earliest possible point.

Stress-related Complications of Occupational Injury

It has been our experience reviewing workers’ compensation claims up to five years post-injury that post-traumatic stress syndromes are a common outcome of occupational injury involving life-threatening or disfiguring injury, or assault and other exposures to crime. The condition typically remains undiagnosed for years, its origins unsuspected by medical professionals, claims administrators and human resource managers, and even the employee him- or herself. When unrecognized, it can slow or even prevent recovery from physical injury.

Disabilities and injuries linked to psychological stress are among the most costly and difficult to manage of all work-related injuries. In the “stress claim”, an employee maintains he or she has been emotionally damaged by an event or conditions at work. Costly and hard to fight, stress claims usually result in litigation and in the separation of the employee. There exists, however, a vastly more frequent but seldom recognized source of stress-related claims. In these cases, serious injury or exposure to life-threatening situations results in undiagnosed and untreated psychological stress conditions that significantly affect the outcome of work-related injuries.

On the basis of our work with traumatic worksite injuries and violent episodes over a wide range of worksites, we estimate that at least half of disputed workers’ compensation claims involve unrecognized and untreated post-traumatic stress conditions or other psychosocial components. In the push to resolve medical problems and determine the employee’s employment status, and because of many systems’ fear and mistrust of mental health intervention, emotional stress and psychosocial issues take a back seat. When no one deals with it, stress can take the form of a number of medical conditions, unrecognized by the employer, the risk manager, the health care provider and the employee him- or herself. Trauma-related stress also typically leads to avoidance of the workplace, which increases the risk of conflicts and disputes regarding return to work and claims of disability.

Many employers and insurance carriers believe that contact with a mental health professional leads directly to an expensive and unmanageable claim. Unfortunately, this is often the case. Statistics bear out that claims for mental stress are more expensive than claims for other kinds of injuries. Furthermore, they are increasing faster than any other kind of injury claim. In the typical “physical-mental” claim scenario, the psychiatrist or psychologist appears only at the point—typically months or even years after the event—when there is a need for expert assessment in a dispute. By this time, the psychological damage has been done. The trauma-related stress reaction may have prevented the employee from returning to the workplace, even though he or she appeared visibly healed. Over time, the untreated stress reaction to the original injury has resulted in a chronic anxiety or depression, a somatic illness or a substance abuse disorder. Indeed, it is rare that mental health intervention is rendered at the point when it can prevent the trauma-related stress reaction and thus help the employee fully recover from the trauma of a serious injury or assault.

With a small measure of planning and proper timing, the costs and suffering associated with injury-related stress are among the most preventable of all injuries. The following are the components of an effective post-injury plan (Braverman 1993a):

Early intervention

Companies should require a brief mental health intervention whenever a severe accident, assault or other traumatic event impacts on an employee. This evaluation should be seen as preventive, rather than as tied to the standard claims procedure. It should be provided even if there is no lost time, injury or need for medical treatment. The intervention should emphasize education and prevention, rather than a strictly clinical approach that may cause the employee to feel stigmatized. The employer, perhaps in conjunction with the insurance provider, should take responsibility for the relatively small cost of providing this service. Care should be taken that only professionals with specialized expertise or training in post-traumatic stress conditions be involved.

Return to work

Any counselling or assessment activity should be coordinated with a return-to-work plan. Employees who have undergone a trauma often feel afraid or tentative about returning to the worksite. Combining brief education and counselling with visits to the workplace during the recovery period has been used to great advantage in accomplishing this transition and speeding return to work. Health professionals can work with the supervisor or manager in developing gradual re-entry into job functioning. Even when there is no remaining physical limitation, emotional factors may necessitate accommodations, such as allowing a bank teller who was robbed to work in another area of the bank for part of the day as she gradually becomes comfortable returning to work at the customer window.

Follow-up

Post-traumatic reactions are often delayed. Follow-up at 1- and 6-month intervals with employees who have returned to work is important. Supervisors are also provided with fact sheets on how to spot possible delayed or long-term problems associated with post-traumatic stress.

Summary: The Link between Post-Traumatic Stress Studies and Occupational Health

Perhaps more than any other health science, occupational medicine is concerned with the relationship between human stress and disease. Indeed, much of the research in human stress in this century has taken place within the occupational health field. As the health sciences in general became more involved in prevention, the workplace has become increasingly important as an arena for research into the contribution of the physical and psychosocial environment to disease and other health outcomes, and into methods for the prevention of stress-related conditions. At the same time, since 1980 a revolution in the study of post-traumatic stress has brought important progress to the understanding of the human stress response. The occupational health practitioner is at the intersection of these increasingly important fields of study.

As the landscape of work undergoes revolutionary transformation, and as we learn more about productivity, coping and the stressful impact of continued change, the line between chronic stress and acute or traumatic stress has begun to blur. The clinical theory of traumatic stress has much to tell us about how to prevent and treat work-related psychological stress. As in all health sciences, knowledge of the causes of a syndrome can help in prevention. In the area of traumatic stress, the workplace has shown itself to be an excellent place to promote health and healing. By being well acquainted with the symptoms and causes of post-traumatic stress reactions, occupational health practitioners can increase their effectiveness as agents of prevention.

Stress and Burnout and their Implication in the Work Environment

“An emerging global economy mandates serious scientific attention to discoveries that foster enhanced human productivity in an ever-changing and technologically sophisticated work world” (Human Capital Initiative 1992). Economic, social, psychological, demographic, political and ecological changes around the world are forcing us to reassess the concept of work, stress and burnout on the workforce.

Productive work “calls for a primary focus on reality external to one self. Work therefore emphasizes the rational aspects of people and problem solving” (Lowman 1993). The affective and mood side of work is becoming an ever-increasing concern as the work environment becomes more complex.

A conflict that may arise between the individual and the world of work is that a transition is called for, for the beginning worker, from the self-centredness of adolescence to the disciplined subordination of personal needs to the demands of the workplace. Many workers need to learn and adapt to the reality that personal feelings and values are often of little importance or relevance to the workplace.

In order to continue a discussion of work-related stress, one needs to define the term, which has been used widely and with varying meanings in the behavioural science literature. Stress involves an interaction between a person and the work environment. Something happens in the work arena which presents the individual with a demand, constraint, request or opportunity for behaviour and consequent response. “There is a potential for stress when an environmental situation is perceived as presenting a demand which threatens to exceed the person’s capabilities and resources for meeting it, under conditions where he/she expects a substantial differential in the rewards and costs from meeting the demand versus not meeting it” (McGrath 1976).

It is appropriate to state that the degree to which the demand exceeds the perceived expectation and the degree of differential rewards expected from meeting or not meeting that demand reflect the amount of stress that the person experiences. McGrath further suggests that stress may present itself in the following ways: “Cognitive-appraisal wherein subjectively experienced stress is contingent upon the person’s perception of the situation. In this category the emotional, physiological and behavioural responses are significantly influenced by the person’s interpretation of the ‘objective’ or external stress situation.”

Another component of stress is the individual’s past experience with a similar situation and his or her empirical response. Along with this is the reinforcement factor, whether positive or negative, successes or failures which can operate to reduce or enhance, respectively, levels of subjectively experienced stress.

Burnout is a form of stress. It is a process defined as a feeling of progressive deterioration and exhaustion and an eventual depletion of energy. It is also often accompanied by a loss of motivation, a feeling that suggests “enough, no more”. It is an overload that tends during the course of time to affect attitudes, mood and general behaviour (Freudenberger 1975; Freudenberger and Richelson 1981). The process is subtle; it develops slowly and sometimes occurs in stages. It is often not perceived by the person most affected, since he or she is the last individual to believe that the process is taking place.

The symptoms of burnout manifest themselves on a physical level as ill-defined psychosomatic complaints, sleep disturbances, excessive fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, backaches, headaches, various skin conditions or vague cardiac pains of an unexplained origin (Freudenberger and North 1986).

Mental and behavioural changes are more subtle. “Burnout is often manifest by a quickness to be irritated, sexual problems (e.g. impotence or frigidity), fault finding, anger and low frustration threshold” (Freudenberger 1984a).

Further affective and mood signs may be progressive detachment, loss of self-confidence and lowered self-esteem, depression, mood swings, an inability to concentrate or pay attention, an increased cynicism and pessimism, as well as a general sense of futility. Over a period of time the contented person becomes angry, the responsive person becomes silent and withdrawn and the optimist becomes a pessimist.

The affect feelings that appear to be most common are anxiety and depression. The anxiety most typically associated with work is performance anxiety. The forms of work conditions that are relevant in promoting this form of anxiety are role ambiguity and role overload (Srivastava 1989).

Wilke (1977) has indicated that “one area that presents particular opportunity for conflict for the personality-disordered individual concerns the hierarchical nature of work organizations. The source of such difficulties can rest with the individual, the organization, or some interactive combination.”

Depressive features are frequently found as part of the presenting symptoms of work-related difficulties. Estimates from epidemiological data suggest that depression affects 8 to 12% of men and 20 to 25% of women. The life expectancy experience of serious depressive reactions virtually assures that workplace issues for many people will be affected at some time by depression (Charney and Weissman 1988).

The seriousness of these observations was validated by a study conducted by Northwestern National Life Insurance Company—“Employee Burnout: America’s Newest Epidemic” (1991). It was conducted among 600 workers nationwide and identified the extent, causes, costs and solutions related to workplace stress. The most striking research findings were that one in three Americans seriously thought about quitting work in 1990 because of job stress, and a similar portion expected to experience job burnout in the future. Nearly half of the 600 respondents experienced stress levels as “extremely or very high.” Workplace changes such as cutting employee benefits, change of ownership, required frequent overtime or reduced workforce tend to speed up job stress.

MacLean (1986) further elaborates on job stressors as uncomfortable or unsafe working conditions, quantitative and qualitative overload, lack of control over the work process and work rate, as well as monotony and boredom.

Additionally, employers are reporting an ever-increasing number of employees with alcohol and drug abuse problems (Freudenberger 1984b). Divorce or other marital problems are frequently reported as employee stressors, as are long-term or acute stressors such as caring for an elderly or disabled relative.

Assessment and classification to diminish the possibility of burnout may be approached from the points of view related to vocational interests, vocational choices or preferences and characteristics of people with different preferences (Holland 1973). One might utilize computer-based vocational guidance systems, or occupational simulation kits (Krumboltz 1971).

Biochemical factors influence personality, and the effects of their balance or imbalance on mood and behaviour are found in the personality changes attendant on menstruation. In the last 25 years a great deal of work has been done on the adrenal catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine and other biogenic amines. These compounds have been related to the experiencing of fear, anger and depression (Barchas et al. 1971).

The most commonly used psychological assessment devices are:

- Eysenck Personality Inventory and Mardsley Personality Inventory

- Gordon Personal Profile

- IPAT Anxiety Scale Questionnaire

- Study of Values

- Holland Vocational Preference Inventory

- Minnesota Vocational Interest Test

- Rorschach Inkblot Test

- Thematic Apperception Test

A discussion of burnout would not be complete without a brief overview of the changing family-work system. Shellenberger, Hoffman and Gerson (1994) indicated that “Families are struggling to survive in an increasingly complex and bewildering world. With more choices than they can consider, people are struggling to find the right balance between work, play, love and family responsibility.”

Concomitantly, women’s work roles are expanding, and over 90% of women in the US cite work as a source of identity and self-worth. In addition to the shifting roles of men and women, the preservation of two incomes sometimes requires changes in living arrangements, including moving for a job, long-distance commuting or establishing separate residences. All of these factors can put a great strain on a relationship and on work.

Solutions to offer to diminish burnout and stress on an individual level are:

- Learn to balance your life.

- Share your thoughts and communicate your concerns.

- Limit alcohol intake.

- Re-evaluate personal attitudes.

- Learn to set priorities.

- Develop interests outside of work.

- Do volunteer work.

- Re-evaluate your need for perfectionism.

- Learn to delegate and ask for assistance.

- Take time off.

- Exercise, and eat nutritional meals.

- Learn to take yourself less seriously.

On a larger scale, it is imperative that government and corporations accommodate to family needs. To reduce or diminish stress in the family-work system will require a significant reconfiguration of the entire structure of work and family life. “A more equitable arrangement in gender relationships and the possible sequencing of work and non-work over the life span with parental leaves of absence and sabbaticals from work becoming common occurrences” (Shellenberger, Hoffman and Gerson 1994).

As indicated by Entin (1994), increased differentiation of self, whether in a family or corporation, has important ramifications in reducing stress, anxiety and burnout.

Individuals need to be more in control of their own lives and take responsibility for their actions; and both individuals and corporations need to re-examine their value systems. Dramatic shifts need to take place. If we do not heed the statistics, then most assuredly burnout and stress will continue to remain the significant problem it has become for all society.

Cognitive Disorders

A cognitive disorder is defined as a significant decline in one’s ability to process and recall information. The DSM IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) describes three major types of cognitive disorder: delirium, dementia and amnestic disorder. A delirium develops over a short period of time and is characterized by an impairment of short-term memory, disorientation and perceptual and language problems. Amnestic disorders are characterized by impairment of memory such that sufferers are unable to learn and recall new information. However, no other declines in cognitive functioning are associated with this type of disorder. Both delirium and amnestic disorders are usually due to the physiological effects of a general medical condition (e.g., head injuries, high fevers) or of substance use. There is little reason to suspect that occupational factors play a direct role in the development of these disorders.

However, research has suggested that occupational factors may influence the likelihood of developing the multiple cognitive deficits involved in dementia. Dementia is characterized by memory impairment and at least one of the following problems: (a) reduced language function; (b) a decline in one’s ability to think abstractly; or (c) an inability to recognize familiar objects even though one’s senses (e.g., vision, hearing, touch) are not impaired. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia.

The prevalence of dementia increases with age. Approximately 3% of people over the age of 65 years will suffer from a severe cognitive impairment during any given year. Recent studies of elderly populations have found a link between a person’s occupational history and his or her likelihood of suffering from dementia. For example, a study of the rural elderly in France (Dartigues et al. 1991) found that people whose primary occupation had been farm worker, farm manager, provider of domestic service or blue-collar worker had a significantly elevated risk of having a severe cognitive impairment when compared to those whose primary occupation had been teacher, manager, executive or professional. Furthermore, this elevated risk was not due to differences between the groups of workers in terms of age, sex, education, drinking of alcoholic beverages, sensory impairments or the taking of psychotropic drugs.

Because dementia is so rare among people younger than 65 years, no study has examined occupation as a risk factor among this population. However, a large study in the United States (Farmer et al. 1995) has shown that people under the age of 65 who have high levels of education are less likely to experience declines in cognitive functioning than are similarly aged people with less education. The authors of this study commented that education level may be a “marker variable” that is actually reflecting the effects of occupational exposures. At this point, such a conclusion is highly speculative.

Although several studies have found an association between one’s principal occupation and dementia among the elderly, the explanation or mechanism underlying the association is not known. One possible explanation is that some occupations involve higher exposure to toxic materials and solvents than do other occupations. For example, there is growing evidence that toxic exposures to pesticides and herbicides can have adverse neurological effects. Indeed, it has been suggested that such exposures may explain the elevated risk of dementia found among farm workers and farm managers in the French study described above. In addition, some evidence suggests that the ingestion of certain minerals (e.g., aluminium and calcium as components of drinking water) may affect the risk of cognitive impairment. Occupations may involve differential exposure to these minerals. Further research is needed to explore possible pathophysiological mechanisms.

Psychosocial stress levels of employees in various occupations may also contribute to the link between occupation and dementia. Cognitive disorders are not among the mental health problems that are commonly thought to be stress related. A review of the role of stress in psychiatric disorders focused on anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and depression, but made no mention of cognitive disorders (Rabkin 1993). One type of disorder, called dissociative amnesia, is characterized by an inability to recall a previous traumatic or stressful event but carries with it no other type of memory impairment. This disorder is obviously stress-related, but is not categorized as a cognitive disorder according to the DSM IV.

Although psychosocial stress has not been explicitly linked to the onset of cognitive disorders, it has been demonstrated that the experience of psychosocial stress affects how people process information and their ability to recall information. The arousal of the autonomic nervous system that often accompanies exposure to stressors alerts a person to the fact that “all is not as expected or as it should be” (Mandler 1993). At first, this arousal may enhance a person’s ability to focus attention on the central issues and to solve problems. However, on the negative side, the arousal uses up some of the “available conscious capacity” or the resources that are available for processing incoming information. Thus, high levels of psychosocial stress ultimately (1) limit one’s ability to scan all of the relevant available information in an orderly fashion, (2) interfere with one’s ability to rapidly detect peripheral cues, (3) decrease one’s ability to sustain focused attention and (4) impair some aspects of memory performance. To date, even though these decrements in information-processing skills can result in some of the symptomatology associated with cognitive disorders, no relationship has been demonstrated between these minor impairments and the likelihood of exhibiting a clinically diagnosed cognitive disorder.

A third possible contributor to the relationship between occupation and cognitive impairment may be the level of mental stimulation demanded by the job. In the study of rural elderly residents in France described above, the occupations associated with the lowest risk of dementia were those that involved substantial intellectual activity (e.g., physician, teacher, lawyer). One hypothesis is that the intellectual activity or mental stimulation inherent in these jobs produces certain biological changes in the brain. These changes, in turn, protect the worker from decline in cognitive function. The well-documented protective effect of education on cognitive functioning is consistent with such a hypothesis.

It is premature to draw any implications for prevention or treatment from the research findings summarized here. Indeed, the association between one’s lifetime principal occupation and the onset of dementia among the elderly may not be due to occupational exposures or the nature of the job. Rather, the relationship between occupation and dementia may be due to differences in the characteristics of workers in various occupations. For example, differences in personal health behaviours or in access to quality medical care may account for at least part of the effect of occupation. None of the published descriptive studies can rule out this possibility. Further research is needed to explore whether specific psychosocial, chemical and physical occupational exposures are contributing to the aetiology of this cognitive disorder.

Karoshi: Death from Overwork

What Is Karoshi?

Karoshi is a Japanese word which means death from overwork. The phenomenon was first identified in Japan, and the word is being adopted internationally (Drinkwater 1992). Uehata (1978) reported 17 karoshi cases at the 51st annual meeting of the Japan Association of Industrial Health. Among them seven cases were compensated as occupational diseases, but ten cases were not. In 1988 a group of lawyers established the National Defense Counsel for Victims of Karoshi (1990) and started telephone consultation to handle inquiries about karoshi-related workers’ compensation insurance. Uehata (1989) described karoshi as a sociomedical term that refers to fatalities or associated work disability due to cardiovascular attacks (such as strokes, myocardial infarction or acute cardiac failure) which could occur when hypertensive arteriosclerotic diseases are aggravated by a heavy workload. Karoshi is not a pure medical term. The media have frequently used the word because it emphasizes that sudden deaths (or disabilities) were caused by overwork and should be compensated. Karoshi has become an important social problem in Japan.

Research on Karoshi

Uehata (1991a) conducted a study of 203 Japanese workers (196 males and seven females) who had cardiovascular attacks. They or their next of kin consulted with him regarding workers’ compensation claims between 1974 and 1990. A total of 174 workers had died; 55 cases had already been compensated as occupational disease. A total of 123 workers had suffered strokes (57 arachnoidal bleedings, 46 cerebral bleedings, 13 cerebral infarctions, seven unknown types); 50, acute heart failure; 27, myocardial infarctions; and four, aortic ruptures. Autopsies were performed in only 16 cases. More than half of the workers had histories of hypertension, diabetes or other atherosclerotic problems. A total of 131 cases had worked for long hours—more than 60 hours per week, more than 50 hours overtime per month or more than half of their fixed holidays. Eighty-eight workers had identifiable trigger events within 24 hours before their attack. Uehata concluded that these were mostly male workers, working for long hours, with other stressful overload, and that these working styles exacerbated their other lifestyle habits and resulted in the attacks, which were finally triggered by minor work-related troubles or events.

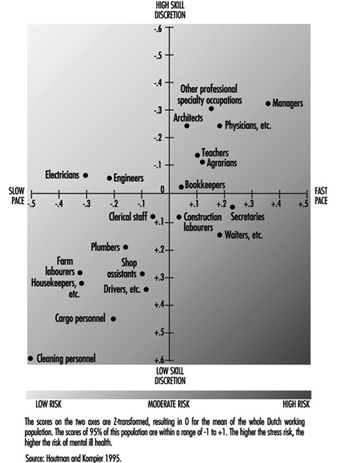

Karasek Model and Karoshi

According to the demand-control model by Karasek (1979), a high-strain job—one with a combination of high demand and low control (decision latitude)—increases the risk of psychological strain and physical illness; an active job—one with a combination of high demand and high control—requires learning motivation to develop new behaviour patterns. Uehata (1991b) reported that the jobs in karoshi cases were characterized by a higher degree of work demands and lower social support, whereas the degree of work control varied greatly. He described the karoshi cases as very delighted and enthusiastic about their work, and consequently likely to ignore their needs for regular rest and so on—even the need for health care. It is suggested that workers in not only high-strain jobs but also active jobs could be at high risk. Managers and engineers have high decision latitude. If they have extremely high demands and are enthusiastic in their work, they may not control their working hours. Such workers may be a risk group for karoshi.

Type A Behaviour Pattern in Japan

Friedman and Rosenman (1959) proposed the concept of Type A behaviour pattern (TABP). Many studies have showed that TABP is related to the prevalence or incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD).

Hayano et al. (1989) investigated the characteristics of TABP in Japanese employees using the Jenkins Activity Survey (JAS). Responses of 1,682 male employees of a telephone company were analysed. The factor structure of the JAS among the Japanese was in most respects equal to that found in the Western Collaborative Group Study (WCGS). However, the average score of factor H (hard-driving and competitiveness) among the Japanese was considerably lower than that in the WCGS.

Monou (1992) reviewed TABP research in Japan and summarized as follows: TABP is less prevalent in Japan than in the United States; the relationship between TABP and coronary heart disease in Japan seems to be significant but weaker than that in the US; TABP among Japanese places more emphasis on “workaholism” and “directivity into the group” than in the US; the percentage of highly hostile individuals in Japan is lower than in the US; there is no relationship between hostility and CHD.

Japanese culture is quite different from those of Western countries. It is strongly influenced by Buddhism and Confucianism. Generally speaking, Japanese workers are organization centred. Cooperation with colleagues is emphasized rather than competition. In Japan, competitiveness is a less important factor for coronary-prone behaviour than job involvement or a tendency to overwork. Direct expression of hostility is suppressed in Japanese society. Hostility may be expressed differently than in Western countries.

Working Hours of Japanese Workers

It is well known that Japanese workers work long hours compared with workers in other developed industrial countries. Normal annual working hours of manufacturing workers in 1993 were 2,017 hours in Japan; 1,904 in the United States; 1,763 in France; and 1,769 in the UK (ILO 1995). However, Japanese working hours are gradually decreasing. Average annual working hours of manufacturing employees in enterprises with 30 employees or more was 2,484 hours in 1960, but 1,957 hours in 1994. Article 32 of the Labor Standards Law, which was revised in 1987, provides for a 40-hour week. The general introduction of the 40-hour week is expected to take place gradually in the 1990s. In 1985, the 5-day work week was granted to 27% of all employees in enterprises with 30 employees or more; in 1993, it was granted to 53% of such employees. The average worker was allowed 16 paid holidays in 1993; however, workers actually used an average of 9 days. In Japan, paid holidays are few, and workers tend to save them to cover absence due to sickness.

Why do Japanese workers work such long hours? Deutschmann (1991) pointed out three structural conditions underlying the present pattern of long working hours in Japan: first, the continuing need of Japanese employees to increase their income; second, the enterprise-centred structure of industrial relations; and third, the holistic style of Japanese personnel management. These conditions were based on historical and cultural factors. Japan was defeated in war in 1945 for the first time in history. After the war Japan was a cheap wage country. The Japanese were used to working long and hard to earn their subsistence. As labour unions were cooperative with employers, there have been relatively few labour disputes in Japan. Japanese companies adopted the seniority-oriented wage system and lifetime employment. The number of hours is a measure of the loyalty and cooperativeness of an employee, and becomes a criterion for promotion. Workers are not forced to work long hours; they are willing to work for their companies, as if the company is their family. Working life has priority over family life. Such long working hours have contributed to the remarkable economic achievements of Japan.

National Survey of Workers’ Health

The Japanese Ministry of Labour conducted surveys on the state of employees’ health in 1982, 1987 and 1992. In the survey in 1992, 12,000 private worksites employing 10 or more workers were identified, and 16,000 individual workers from them were randomly selected nationwide based on industry and job classification to fill out questionnaires. The questionnaires were mailed to a representative at the workplace who then selected workers to complete the survey.

Sixty-five per cent of these workers complained of physical fatigue due to their usual work, and 48% complained of mental fatigue. Fifty-seven per cent of workers stated that they had strong anxieties, worries or stress concerning their job or working life. The prevalence of stressed workers was increasing, as the prevalence had been 55% in 1987 and 51% in 1982. The main causes of stress were: unsatisfactory relations in the workplace, 48%; quality of work, 41%; quantity of work, 34%.

Eighty-six per cent of these worksites conducted periodic health examinations. Worksite health promotion activities were conducted at 44% of the worksites. Of these worksites, 48% had sports events, 46% had exercise programmes and 35% had health counselling.

National Policy to Protect and PromoteWorkers’ Health

The purpose of the Industrial Safety and Health Law in Japan is to secure the safety and health of workers in workplaces as well as to facilitate the establishment of a comfortable working environment. The law states that the employer shall not only comply with the minimum standards for preventing occupational accidents and diseases, but also endeavour to ensure the safety and health of workers in workplaces through the realization of a comfortable working environment and the improvement of working conditions.

Article 69 of the law, amended in 1988, states that the employer shall make continuous and systematic efforts for the maintenance and promotion of workers’ health by taking appropriate measures, such as providing health education and health counselling services to the workers. The Japanese Ministry of Labour publicly announced guidelines for measures to be taken by employers for the maintenance and promotion of workers’ health in 1988. It recommends worksite health promotion programmes called the Total Health Promotion Plan (THP): exercise (training and counselling), health education, psychological counselling and nutritional counselling, based on the health status of employees.

In 1992, the guidelines for the realization of a comfortable working environment were announced by the Ministry of Labour in Japan. The guidelines recommend the following: the working environment should be properly maintained under comfortable conditions; work conditions should be improved to reduce the workload; and facilities should be provided for the welfare of employees who need to recover from fatigue. Low-interest loans and grants for small and medium-sized enterprises for workplace improvement measures have been introduced to facilitate the realization of a comfortable working environment.

Conclusion

The evidence that overwork causes sudden death is still incomplete. More studies are needed to clarify the causal relationship. To prevent karoshi, working hours should be reduced. Japanese national occupational health policy has focused on work hazards and health care of workers with problems. The psychological work environment should be improved as a step towards the goal of a comfortable working environment. Health examinations and health promotion programmes for all workers should be encouraged. These activities will prevent karoshi and reduce stress.

Work and Mental Health

This chapter provides an overview of major types of mental health disorder that can be associated with work—mood and affective disorders (e.g., dissatisfaction), burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychoses, cognitive disorders and substance abuse. The clinical picture, available assessment techniques, aetiological agents and factors, and specific prevention and management measures will be provided. The relationship with work, occupation or branch of industry will be illustrated and discussed where possible.

This introductory article first will provide a general perspective on occupational mental health itself. The concept of mental health will be elaborated upon, and a model will be presented. Next, we will discuss why attention should be paid to mental (ill) health and which occupational groups are at greatest risk. Finally, we will present a general intervention framework for successfully managing work-related mental health problems.

What Is Mental Health: A Conceptual Model

There are many different views about the components and processes of mental health. The concept is heavily value laden, and one definition is unlikely to be agreed upon. Like the strongly associated concept of “stress”, mental health is conceptualized as:

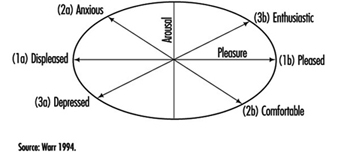

- a state—for example, a state of total psychological and social well-being of an individual in a given sociocultural environment, indicative of positive moods and affects (e.g., pleasure, satisfaction and comfort) or negative ones (e.g., anxiety, depressive mood and dissatisfaction).

- a process indicative of coping behaviour—for example, striving for independence, being autonomous (which are key aspects of mental health).

- the outcome of a process—a chronic condition resulting either from an acute, intense confrontation with a stressor, such as is the case in a post-traumatic stress disorder, or from the continuing presence of a stressor which may not necessarily be intense. This is the case in burnout, as well as in psychoses, major depressive disorders, cognitive disorders and substance abuse. Cognitive disorders and substance abuse are, however, often considered as neurological problems, since pathophysiological processes (e.g., degeneration of the myelin sheath) resulting from ineffective coping or from the stressor itself (alcohol use or occupational exposition to solvents, respectively) can underlie these chronic conditions.

Mental health may also be associated with:

- Person characteristics like “coping styles”—competence (including effective coping, environmental mastery and self-efficacy) and aspiration are characteristic of a mentally healthy person, who shows interest in the environment, engages in motivational activity and seeks to extend him- or herself in ways that are personally significant.

Thus, mental health is conceptualized not only as a process or outcome variable, but also as an independent variable—that is, as a personal characteristic that influences our behaviour.

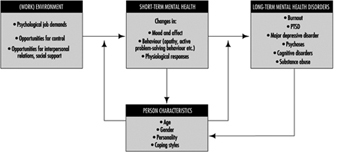

In figure 1 a mental health model is presented. Mental health is determined by environmental characteristics, both in and outside the work situation, and by characteristics of the individual. Major environmental job characteristics are elaborated upon in the chapter “Psychosocial and organizational factors”, but some points on these environmental precursors of mental (ill) health have to be made here as well.

Figure 1. A model for mental health.