Low-back pain is a common ailment in populations of working age. About 80% of people experience low-back pain during their lifetime, and it is one of the most important causes for short- and long-term disability in all occupational groups. Based on the aetiology, low-back pain can be classified into six groups: mechanical, infectious (e.g., tuberculosis), inflammatory (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis), metabolic (e.g., osteoporosis), neoplastic (e.g., cancer) and visceral (pain caused by diseases of the inner organs).

The low-back pain in most people has mechanical causes, which include lumbosacral sprain/strain, degenerative disc disease, spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis and fracture. Here only mechanical low-back pain is considered. Mechanical low-back pain is also called regional low-back pain, which may be local pain or pain radiating to one or both legs (sciatica). It is characteristic for mechanical low-back pain to occur episodically, and in most cases the natural course is favourable. In about half of acute cases low-back pain subsides in two weeks, and in about 90% within two months. About every tenth case is estimated to become chronic, and it is this group of low-back pain patients that accounts for the major proportion of the costs due to low-back disorders.

Structure and Function

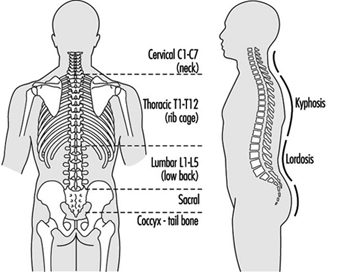

Due to upright posture the structure of the lower part of the human spine (lumbosacral spine) differs anatomically from that of most vertebrate animals. The upright posture also increases mechanical forces on the structures in the lumbosacral spine. Normally the lumbar spine has five vertebrae. The sacrum is rigid and the tail (coccyx) has no function in human beings as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. The spine, its vertebrae and curvature.

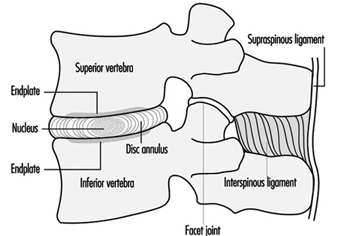

The vertebrae are bound together by intervertebral discs between the vertebral bodies, and by ligaments and muscles. These soft-tissue bindings make the spine flexible. Two adjacent vertebrae form a functional unit, as shown in figure 2. The vertebral bodies and the discs are the weight-bearing elements of the spine. The posterior parts of the vertebrae form the neural arch that protects the nerves in the spinal canal. The vertebral arches are attached to each other via facet joints (zygapophyseal joints) that determine the direction of motion. The vertebral arches are also bound together by numerous ligaments that determine the range of motion in the spine. The muscles that extend the trunk backward (extensors) are attached to the vertebral arches. Important attachment sites are three bony projections (two lateral and the spinal process) of the vertebral arches.

Figure 2. The basic functional unit of the spine.

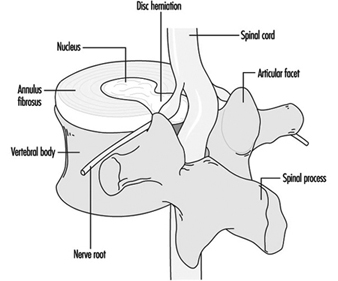

The spinal cord terminates at the level of the highest lumbar vertebrae (L1-L2). The lumbar spinal canal is filled by the extension of the spinal cord, cauda equina, which is composed of the spinal nerve roots. The nerve roots exit the spinal canal pairwise through intervertebral openings (foramina). A branch innervating the tissues in the back departs from each of the spinal nerve roots. There are nerve endings transmitting pain sensations (nociceptive endings) in muscles, ligaments and joints. In a healthy intervertebral disc there are no such nerve endings except for the outermost parts of the annulus. Yet, the disc is considered the most important source of low-back pain. Annular ruptures are known to be painful. As a sequel of disc degeneration a herniation of the semigelatinous inner part of the intervertebral disc, the nucleus, can occur into the spinal canal and lead to compression and/or inflammation of a spinal nerve along with symptoms and signs of sciatica, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Herniation of the intervertebrai disc.

Muscles are responsible for the stability and motion of the back. Back muscles bend the trunk backward (extension), and abdominal muscles bend it forward (flexion). Fatigue due to sustained or repetitive loading or sudden overexertion of muscles or ligaments can cause low-back pain, albeit the exact origin of such pain is difficult to localize. There is controversy about the role of soft tissue injuries in low-back disorders.

Low-Back Pain

Occurrence

The prevalence estimates of low-back pain vary depending on the definitions used in different surveys. The prevalence rates of low-back pain syndromes in the Finnish general population over 30 years of age are given in table 1. Three in four people have experienced low-back pain (and one in three, sciatic pain) during their lifetime. Every month one in five people suffers from low-back or sciatic pain, and at any point in time, one in six people has a clinically verifiable low-back pain syndrome. Sciatica or herniated intervertebral disc is less prevalent and afflicts 4% of the population. About half of those with a low-back pain syndrome have functional impairment, and the impairment is severe in 5%. Sciatica is more common among men than among women, but other low-back disorders are equally common. Low-back pain is relatively uncommon before the age of 20, but then there is a steady increase in the prevalence until the age of 65, after which there is a decline.

Table 1. Prevalence of back disorders in the Finnish population over 30 years of age, percentages.

|

Men+ |

Women+ |

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of back pain |

76.3 |

73.3 |

|

Lifetime prevalence of sciatic pain |

34.6 |

38.8 |

|

Five-year prevalence of sciatic pain having caused bedrest for at least two weeks |

17.3 |

19.4 |

|

One-month prevalence of low-back or sciatic pain |

19.4 |

23.3 |

|

Point prevalence of clinically verified: |

||

|

Low-back pain syndrome |

17.5 |

16.3 |

|

Sciatica or prolapsed disc* |

5.1 |

3.7 |

+ age-adjusted

* p 0.005

Source: Adapted from Heliövaara et al. 1993.

The prevalence of degenerative changes in the lumbar spine increases with increasing age. About half of 35- to 44-year-old men and nine out of ten men 65 years or older have radiographic signs of disc degeneration of the lumbar spine. Signs of severe disc degeneration are noted in 5 and 38%, respectively. Degener-ative changes are slightly more common in men than in women. People who have degenerative changes in the lumbar spine have low-back pain more frequently than those without, but degener-ative changes are also common among asymptomatic people. In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), disc degeneration has been found in 6% of asymptomatic women 20 years or younger and in 79% of those 60 years or older.

In general, low-back pain is more common in blue-collar occupations than in white-collar occupations. In the United States, materials handlers, nurses’ aides and truck drivers have the highest rates of compensated back injuries.

Risk factors at work

Epidemiological studies have quite consistently found that low-back pain, sciatica or herniated intervertebral disc and degener-ative changes of the lumbar spine are associated with heavy physical work. Little is known, however, of the acceptable limits of physical load on the back.

Low-back pain is related to frequent or heavy lifting, carrying, pulling and pushing. High tensile forces are directed to the muscles and ligaments, and high compression to the bones and joint surfaces. These forces can cause mechanical injuries to the vertebral bodies, intervertebral discs, ligaments and the posterior parts of the vertebrae. The injuries may be caused by sudden overloads or fatigue due to repetitive loading. Repeated microtrauma, which may even occur without being noticed, have been proposed as a cause for degeneration of the lumbar spine.

Low-back pain is also associated with frequent or prolonged twisting, bending or other non-neutral trunk postures. Motion is necessary for the nutrition of the intervertebral disc and static postures may impair the nutrition. In other soft tissues, fatigue can develop. Also prolonged sitting in one position (for instance, machine seamstresses or motor vehicle drivers) increases the risk of low-back pain.

Prolonged driving of motor vehicles has been found to increase the risk of low-back pain and sciatica or herniated disc. Drivers are exposed to whole-body vibration that has an adverse effect on disc nutrition. Also sudden impulses from rough roads, postural stress and materials handling by professional drivers may contribute to the risk.

An obvious cause for back injuries is direct trauma caused by an accident such as falling or slipping. In addition to the acute injuries, there is evidence that traumatic back injuries contribute substantially to the development of chronic low-back syndromes.

Low-back pain is associated with various psychosocial factors at work, such as monotonous work and working under time pressure, and poor social support from co-workers and superiors. The psychosocial factors affect reporting and recovery from low-back pain, but there is controversy about their aetiological role.

Individual risk factors

Height and overweight: Evidence for a relationship of low-back pain with body stature and overweight is contradictory. Evidence is, however, quite convincing for a relationship between sciatica or herniated disc and tallness. Tall people may have a nutritional disadvantage due to a greater disc volume, and they may also have ergonomic problems at the worksite.

Physical fitness: Study results on an association between physical fitness and low-back pain are inconsistent. Low-back pain is more common in people who have less strength than their job requires. In some studies poor aerobic capacity has not been found to predict future low-back pain or injury claims. The least fit people may have an increased overall risk for back injuries, but the most fit people may have the most expensive injuries. In one study, good back muscle endurance prevented first-time occurrence of low-back pain.

There is considerable variation in the mobility of the lumbar spine among people. People with acute and chronic low-back pain have reduced mobility, but in prospective studies mobility has not predicted the incidence of low-back pain.

Smoking: Several studies have shown that smoking is associated with an increase in the risk of low-back pain and herniated disc. Smoking also seems to enhance disc degeneration. In experimental studies, smoking has been found to impair the nutrition of the disc.

Structural factors: Congenital defects of the vertebrae as well as unequal leg length can cause abnormal loading in the spine. Such factors are, however, not considered very important in the caus-ation of low-back pain. Narrow spinal canal predisposes to nerve root compression and sciatica.

Psychological factors: Chronic low-back pain is associated with psychological factors (e.g., depression), but not all people who suffer from chronic low-back pain have psychological problems. A variety of methods have been used to differentiate low-back pain caused by psychological factors from low-back pain caused by physical factors, but the results have been contradictory. Mental stress symptoms are more common among people with low-back pain than among symptomless people, and mental stress even seems to predict the incidence of low-back pain in the future.

Prevention

The accumulated knowledge based on epidemiological studies on the risk factors is largely qualitative and thus can give only broad guidelines for the planning of preventive programmes. There are three principal approaches in prevention of work-related low-back disorders: ergonomic job design, education and training, and worker selection.

Job design

It is widely believed that the most effective means to prevent work-related low-back disorders is job design. An ergonomic intervention should address the following parameters (shown in table 2).

Table 2. Parameters which should be addressed in order to reduce the risks for low-back pain at work.

|

Parameter |

Example |

|

1. Load |

The weight of the object handled, the size of the object handled |

|

2. Object design |

The shape, location and size of handles |

|

3. Lifting technique |

The distance from the centre of gravity of the object and the worker, twisting motions |

|

4. Workplace layout |

The spatial features of the task, such as carrying distance, range of motion, obstacles such as stairs |

|

5. Task design |

Frequency and duration of the tasks |

|

6. Psychology |

Job satisfaction, autonomy and control, expectations |

|

7. Environment |

Temperature, humidity, noise, foot traction, whole-body vibration |

|

8. Work organization |

Team work, incentives, shifts, job rotation, machine pacing, job security. |

Source: Adapted from Halpern 1992.

Most ergonomic interventions modify the loads, the design of objects handled, lifting techniques, workplace layout and task design. The effectiveness of these measures in controlling the occurrence of low-back pain or medical costs has not been clearly demonstrated. It may be most efficient to reduce the peak loads. One suggested approach is to design a job so that it is within the physical capacity of a large percentage of the working population (Waters et al. 1993). In static jobs restoration of motion can be achieved by restructuring the job, by job rotation or job enrichment.

Education and training

Workers should be trained to perform their work appropriately and safely. Education and training of workers in safe lifting have been widely implemented, but the results have not been convincing. There is general agreement that it is beneficial to keep the load close to the body and to avoid jerking and twisting, but as to the advantages of leg lift and back lift, the opinions of the experts are conflicting.

If mismatch between job demands and the strength of workers is detected and job redesign is not possible, a fitness training programme should be provided for the workers.

In prevention of disability due to low-back pain or chronicity, back school has proven effective in subacute cases, and general fitness training in subchronic cases.

Training needs to be extended also to management. Aspects of management training include early intervention, initial conservative treatment, patient follow-up, job placement and enforcement of safety rules. Active management programmes can significantly reduce long-term disability claims and accident rates.

Medical personnel should be trained in the benefits of early intervention, conservative treatment, patient follow-up and job placement techniques. The Quebec Task Force report on the management of activity-related spinal disorders and other clinical practice guidelines gives sound guidance for proper treatment. (Spitzer et al. 1987; AHCPR 1994.)

Worker selection

In general, pre-employment selection of workers is not considered an appropriate measure for prevention of work-related low-back pain. History of previous back trouble, radiographs of the lumbar spine, general strength and fitness testing—none of these has shown good enough sensitivity and specificity in identifying persons with an increased risk for future low-back trouble. The use of these measures in pre-employment screening can lead to undue discrimination against certain groups of workers. There are, however, some special occupational groups (e.g., fire-fighters and police officers) in which pre-employment screening can be considered appropriate.

Clinical characteristics

The exact origin of low-back pain often cannot be determined, which is reflected as difficulties in the classification of low-back disorders. To a great extent the classification relies on symptom characteristics supported by clinical examination or by imaging results. Basically, in clinical physical examination patients with sciatica caused by compression and/or inflammation of a spinal nerve root can be diagnosed. As to many other clinical entities, such as facet syndrome, fibrositis, muscular spasms, lumbar compartment syndrome or sacro-iliac syndrome, clinical verification has proven unreliable.

As an attempt to resolve the confusion the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders carried out a comprehensive and critical literature review and ended up recommending the use of the classification for low-back pain patients shown in table 3.

Table 3. Classification of low-back disorders according to the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders

1. Pain

2. Pain with radiation to lower limb proximally

3. Pain with radiation to lower limb distally

4. Pain with radiation to lower limb and neurological signs

5. Presumptive compression of a spinal nerve root on a simple radiogram (i.e., spinal instability or fracture)

6. Compression of a spinal nerve root confirmed by: Specific imaging techniques (computerized tomography,

myelography, or magnetic resonance imaging), Other diagnostic techniques (e.g., electromyography,

venography)

7. Spinal stenosis

8. Postsurgical status, 1-6 weeks after intervention

9. Postsurgical status, >6 weeks after intervention

9.1. Asymptomatic

9.2. Symptomatic

10. Chronic pain syndrome

11. Other diagnoses

For categories 1-4, additional classification is based on

(a) Duration of symptoms (7 weeks),

(b) Working status (working; idle, i.e., absent from work, unemployed or inactive).

Source: Spitzer et al. 1987.

For each category, appropriate treatment measures are given in the report, based on critical review of the literature.

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis means a defect in the vertebral arch (pars inter- articularis or isthmus), and spondylolisthesis denotes forward displacement of a vertebral body relative to the vertebra below. The derangement occurs most frequently at the fifth lumbar vertebra.

Spondylolisthesis can be caused by congenital abnormalities, by a fatigue fracture or an acute fracture, instability between two adjacent vertebrae due to degeneration, and by infectious or neo- plastic diseases.

The prevalence of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis ranges from 3 to 7%, but in certain ethnic groups the prevalence is considerably higher (Lapps, 13%; Eskimos in Alaska, 25 to 45%; Ainus in Japan, 41%), which indicates a genetic predisposition. Spondylolysis is equally common in people with and without low-back pain, but people with spondylolisthesis are susceptible to recurrent low-back pain.

An acute traumatic spondylolisthesis can develop due to an accident at work. The prevalence is increased among athletes in certain athletic activities, such as American football, gymnastics, javelin throwing, judo and weight lifting, but there is no evidence that physical exertion at work would cause spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Piriformis syndrome

Piriformis syndrome is an uncommon and controversial cause for sciatica characterized by symptoms and signs of sciatic nerve compression at the region of the piriformis muscle where it passes through the greater sciatic notch. No epidemiological data on the prevalence of this syndrome are available. The present knowledge is based on case reports and case series. Symptoms are aggravated by prolonged hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Recently piriformis muscle enlargement has been verified in some cases of piriformis syndrome by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. The syndrome can result from an injury to the piriformis muscle.