The primary functions of the employee health service are treatment of acute injuries and illnesses occurring in the workplace, conducting fitness-to-work examinations (Cowell 1986) and the prevention, detection and treatment of work-related injuries and illnesses. However, it may also play a significant role in preventive and health maintenance programs. In this article, particular attention will be paid to the “hands on” services that this corporate unit may provide in this connection.

Since its inception, the employee health unit has served as a focal point for prevention of non-occupational health problems. Traditional activities have included distribution of health education materials; the production of health promotion articles by staff members for publication in company periodicals; and, perhaps most important, seeing to it that occupational physicians and nurses remain alert to the advisability of preventive health counseling in the course of encounters with employees with incidentally observed potential or emerging health problems. Periodic health surveillance examinations for potential effects of occupational hazards have frequently demonstrated an incipient or early non-occupational health problem.

The medical director is strategically situated to play a central role in the organization’s preventive programs. Significant advantages attaching to this position include the opportunity to build preventive components into work-related services, the generally high regard of employees, and already established relationships with high-level managers through which desirable changes in work structure and environment can be implemented and the resources for an effective prevention program obtained.

In some instances, non-occupational preventive programs are placed elsewhere in the organization, for example, in the personnel or human resources departments. This is generally unwise but may be necessary when, for example, these programs are provided by different outside contractors. Where such separation does exist, there should at least be coordination and close collaboration with the employee health service.

Depending upon the nature and location of the worksite and the organization’s commitment to prevention, these services may be very comprehensive, covering virtually all aspects of health care, or they may be quite minimal, providing only limited health information materials. Comprehensive programs are desirable when the worksite is located in an isolated area where community-based services are lacking; in such situations, the employer must provide extensive health care services, often to employees’ dependants as well, to attract and retain a loyal, healthy and productive workforce. The other end of the spectrum is usually found in situations where there is a strong community-based health care system or where the organization is small, poorly resourced or, regardless of size, indifferent to the health and welfare of the workforce.

In what follows, neither of these extremes will be the subject of consideration; instead, attention will be focused on the more common and desirable situation where the activities and programs provided by the employee health unit complement and supplement services provided in the community.

Organization of Preventive Services

Typically, worksite preventive services include health education and training, periodic health assessments and examinations, screening programs for particular health problems, and health counseling.

Participation in any of these activities should be viewed as voluntary, and any individual findings and recommendations must be held confidential between the employee health staff and the employee, although, with the consent of the employee, reports may be forwarded to his or her personal physician. To operate otherwise is to preclude any program from ever being truly effective. Hard lessons have been learned and are continuing to be learned about the importance of such considerations. Programs which do not enjoy employees’ credibility and trust will have no or only half-hearted participation. And if the programs are perceived as being offered by management in some self-serving or manipulative way, they have little chance of achieving any good.

Worksite preventive health services ideally are provided by staff attached to the employee health unit, often in collaboration with an in-house employee education department (where one exists). When the staff lacks time or the necessary expertise or when special equipment is required (e.g., with mammography), the services may be obtained by contracting with an outside provider. Reflecting the peculiarities of some organizations, such contracts are sometimes arranged by a manager outside the employee health unit—this is often the case in decentralized organizations when such service contracts are negotiated with community-based providers by the local plant managers. However, it is desirable that the medical director be responsible for setting out the framework of the contract, verifying the capabilities of potential providers and monitoring their performance. In such instances, while aggregate reports may be provided to management, individual results should be forwarded to and retained by the employee health service or maintained in sequestered confidential files by the contractor. At no time should such health information be allowed to form part of the employee’s human resources file. One of the great advantages of having an occupational health unit is not only being able to keep health records separate from other company records under the supervision of an occupational health professional but, also, the opportunity to use this information as the basis of a discreet follow-up to be sure that important medical recommendations are not ignored. Ideally, the employee health unit, where possible in concert with the employee’s personal physician, will provide or oversee the provision of recommended diagnostic or therapeutic services. Other members of the employee health service staff, such as physical therapists, massage therapists, exercise specialists, nutritionists, psychologists and health counselors will also lend their special expertise as required.

The health promotion and protection activities of the employee health unit must complement its primary role of preventing and handling work-related injury and illness. When properly introduced and managed, they will greatly enhance the basic occupational health and safety program but at no time should they displace or dominate it. Placing responsibility for the preventive health services in the employee health unit will facilitate the seamless integration of both programs and make for optimal utilization of critical resources.

Program Elements

Education and training

The goal here is informing and motivating employees—and their dependants—to select and maintain a healthier lifestyle. The intent is to empower the employees to change their own health behavior so they will live longer, healthier, more productive and enjoyable lives.

A variety of communication techniques and presentation styles may be used. A series of attractive, easy-to-read pamphlets can be very useful where there are budget constraints. They may be offered in waiting-room racks, distributed by company mail, or mailed to employees’ homes. They are perhaps most useful when handed to the employee as a particular health issue is being discussed. The medical director or the person directing the preventive program must take pains to be sure that their content is accurate, relevant and presented in language and terms understood by the employees (separate editions may be required for different cohorts of a diverse workforce).

In-plant meetings may be arranged for presentations by employee health staff or invited speakers on health topics of interest. “Brown bag” lunch hour meetings (i.e., employees bring picnic lunches to the meeting and eat while they listen) are a popular mechanism for holding such meetings without interfering with work schedules. Small interactive focus groups led by a well-informed health professional are especially beneficial for workers sharing a particular health problem; peer pressure often constitutes a powerful motivation for compliance with health recommendations. One-on-one counseling, of course, is excellent but very labor-intensive and should be reserved for special situations only. However, access to a source of reliable information should always be available to employees who may have questions.

Topics may include smoking cessation, stress management, alcohol and drug consumption, nutrition and weight control, immunizations, travel advice and sexually-transmitted diseases. Special emphasis is often given to controlling such risk factors for cardiovascular and heart disease as hypertension and abnormal blood lipid patterns. Other topics often covered include cancer, diabetes, allergies, self-care for common minor ailments, and safety in the home and on the road.

Certain topics lend themselves to active demonstration and participation. These include training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid training, exercises to prevent repetitive strain and back pain, relaxation exercises, and self-defense instruction, especially popular among women.

Finally, periodic health fairs with exhibits by local voluntary health agencies and booths offering mass screening procedures are a popular way of generating excitement and interest.

Periodic medical examinations

In addition to the required or recommended periodic health surveillance examinations for employees exposed to particular work or environmental hazards, many employee health units offer more or less comprehensive periodic medical check-ups. Where personnel and equipment resources are limited, arrangements may be made to have them performed, often at the employer’s expense, by local facilities or in private physicians’ offices (i.e., by contractors). For worksites in communities where such services are not available, arrangements may be made for a vendor to bring a mobile examination unit into the plant or set up examination vans in the parking area.

Originally, in most organizations, these examinations were made available only to executives and senior managers. In some, they were extended down into the ranks to employees who had rendered a required number of years of service or who had a known medical problem. They frequently included a complete medical history and physical examination supplemented by an extensive battery of laboratory tests, x-ray examinations, electrocardiograms and stress tests, and exploration of all available body orifices. As long as the company was willing to pay their fees, examination facilities with an entrepreneurial bent were quick to add tests as new technology became available. In organizations prepared to offer even more elaborate service, the examinations were provided as part of a short stay at a popular health resort. While they often turned up important and useful findings, false positives were also frequent and, to say the least, examinations conducted in these surroundings were expensive.

In recent decades, reflecting growing economic pressures, a trend toward egalitarianism and, particularly, the marshalling of evidence regarding the advisability and utility of the different elements in these examinations, have led to their being simultaneously made more widely available in the workforce and less comprehensive.

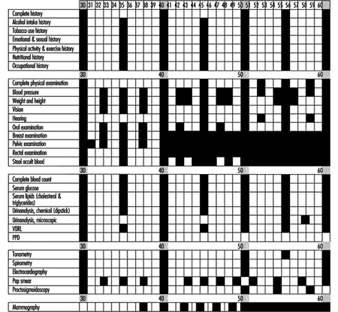

The US Preventive Services Task Force published an assessment of the effectiveness of 169 preventive interventions (1989). Figure 1 presents a useful lifetime schedule of preventive examinations and tests for healthy adults in low-risk managerial positions (Guidotti, Cowell and Jamieson 1989) Thanks to such efforts, periodic medical examinations are becoming less costly and more efficient.

Figure 1. Lifetime health monitoring programme.

Periodic health screening

These programs are designed to detect as early as possible health conditions or actual disease processes which are amenable to early intervention for cure or control and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with poor lifestyle habits, which if changed will prevent or delay the occurrence of disease or premature aging.

The focus is usually towards cardiorespiratory, metabolic (diabetes) and musculoskeletal conditions (back, repetitive strain), and early cancer detection (colorectal, lung, uterus and breast).

Some organizations offer a periodic health risk appraisal (HRA) in the form of a questionnaire probing health habits and potentially significant symptoms often supplemented by such physical measurements as height and weight, skin-fold thickness, blood pressure, “stick test” urinalysis and “finger-stick” blood cholesterol. Others conduct mass screening programs aimed at individual health problems; those aimed at examining subjects for hypertension, diabetes, blood cholesterol level and cancer are most common. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss which screening tests are most useful. However, the medical director may play a critical role in selecting the procedures most appropriate for the population and in evaluating the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of the particular tests being considered. Particularly when temporary staff or outside providers are employed for such procedures, it is important that the medical director verify their qualifications and training in order to assure the quality of their performance. Equally important are prompt communication of the results to those being screened, the ready availability of confirmatory tests and further diagnostic procedures for those with positive or equivocal results, access to reliable information for those who may have questions, and an organized follow-up system to encourage compliance with the recommendations. Where there is no employee health service or its involvement in the screening program is precluded, these considerations are often neglected, with the result that the value of the program is threatened.

Physical conditioning

In many larger organizations, physical fitness programs constitute the core of the health promotion and maintenance program. These include aerobic activities to condition the heart and lungs, and strength and stretching exercises to condition the musculoskeletal system.

In organizations with an in-plant exercise facility, it is often placed under the direction of the employee health service. With such a linkage, it becomes available not only for fitness programs but also for preventive and remedial exercises for back pain, hand and shoulder syndromes, and other injuries. It also facilitates medical monitoring of special exercise programs for employees who have returned to work following pregnancy, surgery or myocardial infarction.

Physical conditioning programs can be effective, but they must be structured and guided by trained personnel who know how to guide the physically unfit and impaired to a state of proper physical fitness. To avoid potentially adverse effects, each individual entering a fitness program should have an appropriate medical evaluation, which may be performed by the employee health service.

Program Evaluation

The medical director is in a uniquely advantageous position to evaluate the organization’s health education and promotion program. Cumulative data from periodic health risk appraisals, medical examinations and screenings, visits to the employee health service, absences due to illness and injury, and so on, aggregated for a particular cohort of employees or the workforce as a whole, can be collated with productivity assessments, worker’s compensation and health insurance costs and other management information to provide, over time, an estimate of the effectiveness of the program. Such analyses may also identify gaps and deficiencies suggesting the need for modification of the program and, at the same time, may demonstrate to management the wisdom of continuing allocation of the required resources. Formulas for calculating the cost/benefit of these programs have been published (Guidotti, Cowell and Jamieson 1989).

Conclusion

There is ample evidence in the world literature supporting worksite preventive health programs (Pelletier 1991 and 1993). The employee health service is a uniquely advantageous venue for conducting these programs or, at the very least, participating in their design and monitoring their implementation and results. The medical director is strategically placed to integrate these programs with activities directed at occupational health and safety in ways that will promote both aims for the benefit of both individual employees (and their families, when included in the program) and the organization.