The rationale for worksite health promotion and protection programs and approaches to their implementation have been discussed in other articles in this chapter. The greatest activity in these initiatives has taken place in large organizations that have the resources to implement comprehensive programs. However, the majority of the workforce is employed in small organizations where the health and well-being of individual workers is likely to have a greater impact on productive capacity and, ultimately, the success of the enterprise. Recognizing this, small firms have begun to pay more attention to the relationship between preventive health practices and productive, vital employees. Increasing numbers of small firms are finding that, with the help of business coalitions, community resources, public and voluntary health agencies, and creative, modest strategies designed to meet their specific needs, they can implement successful yet low-cost programs that yield significant benefits.

Over the last decade, the number of health promotion programs in small organizations has increased significantly. This trend is important as regards both the progress it represents in worksite health promotion and its implication for the nation’s future health care agenda. This article will explore some of the varied challenges faced by small organizations in implementing these programs and describe some of the strategies adopted by those who have overcome them. It is derived in part from a 1992 paper generated by a symposium on small business and health promotion sponsored by the Washington Business Group on Health, the Office of Disease Prevention of the US Public Health Service and the US Small Business Administration (Muchnick-Baku and Orrick 1992). By way of example, it will highlight some organizations that are succeeding through ingenuity and determination in implementing effective programs with limited resources.

Perceived Barriers to Small Business Programs

While many owners of small firms are supportive of the concept of worksite health promotion, they may hesitate to implement a program in the face of the following perceived barriers (Muchnick-Baku and Orrick 1992):

- “It’s too costly.” A common misconception is that worksite health promotion is too costly for a small business. However, some firms provide programmes by making creative use of free or low-cost community resources. For example, the New York Business Group on Health, a health-action coalition with over 250 member organizations in the New York City Metropolitan Area regularly offered a workshop entitled Wellness On a Shoe String that was aimed primarily at small businesses and highlighted materials available at little or no cost from local health agencies.

- “It’s too complicated.” Another fallacy is that health promotion programmes are too elaborate to fit into the structure of the average small business. However, small firms can begin their efforts very modestly and gradually make them more comprehensive as additional needs are recognized. This is illustrated by Sani-Dairy, a small business in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, that began with a home-grown monthly health promotion publication for employees and their families produced by four employees as an “ extracurricular” activity in addition to their regular duties. Then, they began to plan various health promotion events throughout the year. Unlike many small businesses of this size, Sani-Dairy emphasizes disease prevention in its medical programme. Small companies can also reduce the complexity of health promotion programmes by offering health promotion services less frequently than larger companies. Newsletters and health education materials can be distributed quarterly instead of monthly; a more limited number of health seminars can be held at appropriate seasons of the year or linked to annual national campaigns such as Heart Month, the Great American Smoke Out or Cancer Prevention Week in the United States.

- “It hasn’t been proven that the programmes work.” Small businesses simply do not have the time or the resources to do formal cost-benefit analyses of their health promotion programmes. They are forced to rely on anecdotal experience (which may often be misleading) or on inference from the research done in large-firm settings. “What we try to do is learn from the bigger companies,” says Shawn Connors, President of The International Health Awareness Center, “and we extrapolate their information. When they show that they’re saving money, we believe the same thing is happening to us.” While much of the published research attempting to validate the effectiveness of health promotion is flawed, Pelletier has found ample evidence in the literature to confirm impressions of its value (Pelletier 1991 and 1993).

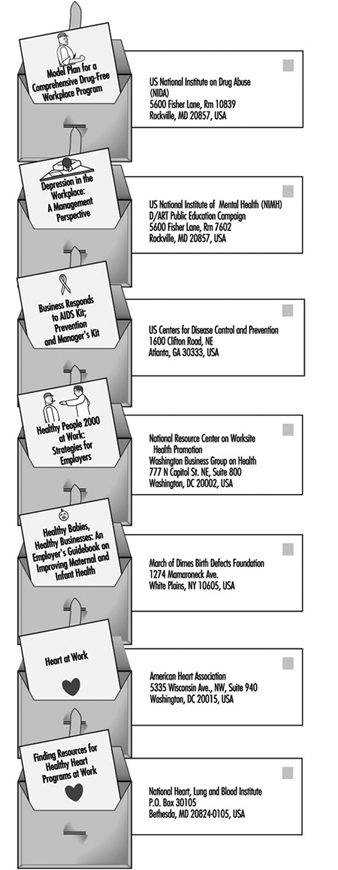

- “We don’t have the expertise to design a programme.” While this is true for most managers of small businesses, it need not present a barrier. Many of the governmental and voluntary health agencies provide free or low-cost kits with detailed instructions and sample materials (see figure 1) for presenting a health promotion programme. In addition, many offer expert advice and consulting services. Finally, in most larger communities and many universities, there are qualified consultants with whom one may negotiate short-term contracts for relatively modest fees covering onsite help in tailoring a particular health promotion programme to the needs and circumstances of a small business and guiding its implementation.

- “We’re not big enough-we don’t have the space.” This is true for most small organizations but it need not stop a good programme. The employer can “buy into” programmes offered in the neighborhood by local hospitals, voluntary health agencies, medical groups and community organizations by subsidizing all or part of any fees that are not covered by the group health insurance plan. Many of these activities are available outside of working hours in the evening or on weekends, obviating the necessity of releasing participating employees from the workplace.

Figure 1. Examples of "do-it-yourself" kits for worksite health promotion programmes in the United States.

Advantages of the Small Worksite

While small businesses do face significant challenges related to financial and administrative resources, they also have advantages. These include (Muchnick-Baku and Orrick 1992):

- Family orientation. The smaller the organization, the more likely it is that employers know their employees and their families. This can facilitate health promotion becoming a corporate-family affair building bonds while promoting health.

- Common work cultures. Small organizations have less diversity among employees than do larger organizations, making it easier to develop more cohesive programmes.

- Interdependency of employees. Members of small units are more dependent on each other. An employee absent because of illness, particularly if prolonged, means a significant loss of productivity and imposes a burden on co-workers. At the same time, the closeness of members of the unit makes peer pressure a more effective stimulant to participation in health promotion activities.

- Approachability of top management. In a smaller organization, management is more accessible, more familiar with the employees and more likely to be aware of their personal problems and needs. Furthermore, the smaller the organization, the more promptly the owner/chief operating officer is likely to become directly involved in making decisions about new programme activities, without the often stultifying effects of the bureaucracy found in most large organizations. In a small firm, that key person is more apt to provide the top-level support so vital to the success of worksite health promotion programmes.

- Effective use of resources. Because they are usually so limited, small businesses tend to be more efficient in the use of their resources. They are more likely to turn to community resources such as voluntary, government and entrepreneurial health and social agencies, hospitals and schools for inexpensive means of providing information and education to employees and their families (see figure 1).

Health Insurance and Health Promotionin Small Businesses

The smaller the firm, the less likely it is to provide group health insurance to employees and their dependants. It is difficult for an employer to claim concern for employees’ health as a basis for offering health promotion activities when basic health insurance is not made available. Even when it is made accessible, exigencies of cost restrict many small businesses to “bare bones” health insurance programs with very limited coverage.

On the other hand, many group plans do cover periodic medical examinations, mammography, Pap smears, immunizations and well baby/child care. Unfortunately, the out-of-pocket cost of covering the deductible fees and co-payments required before insured benefits are payable often acts as a deterrent to using these preventive services. To overcome this, some employers have arranged to reimburse employees for all or part of these expenditures; others find it less troublesome and costly simply to pay for them as an operating expense.

In addition to including preventive services in their coverage, some health insurance carriers offer health promotion programs to group policy holders usually for a fee but sometimes without extra charges. These programs generally focus on printed and audio-visual materials, but some are more comprehensive. Some are particularly suitable for small businesses.

In a growing number of areas, businesses and other types of organizations have formed “health-action” coalitions to develop information and understanding as well as responses to the health-related problems besetting them and their communities. Many of these coalitions provide their members with assistance in designing and implementing worksite health promotion programs. In addition, wellness councils have been appearing in a growing number of communities where they encourage the implementation of worksite as well as community-wide health promotion activities.

Suggestions for Small Businesses

The following suggestions will help to ensure the successful initiation and operation of a health promotion program in a small business:

- Integrate the programme with other company activities. The programme will be more effective and less expensive when it is integrated with the employee group health insurance and benefit plans, the labour relations policies and the corporate environment, and the company’s business strategy. Most important, it must be coordinated with the company’s occupational and environmental health and safety policies and practices.

- Analyze cost data for both employees and the company. What employees want, what they need, and what the company can afford can be vastly different. The company must be able to allocate the resources required for the programme in terms of both the financial outlays and the time and effort of employees involved. It would be futile to launch a programme that could not be continued for lack of resources. At the same time, budget projections should include increases in resource allocations to cover expansion of the programme as it takes hold and grows.

- Involve employees and their representatives. A cross-section of the workforce-i.e., top management, supervisors and rank-and-file workers-should be involved in designing, implementing and evaluating the programme. Where there is a labour union, its leadership and shop stewards should be similarly involved. Often an invitation to co-sponsor the programme will defuse a union’s latent opposition to company programmes intended to enhance employee welfare if that exists; it may also serve to stimulate the union to work for replication of the programme by other companies in the same industry or area.

- Involve employees’ spouses and dependants. Health habits usually are characteristics of the family. Educational materials should be addressed to the home and, to the extent possible, employees’ spouses and other family members should be encouraged to participate in the activities.

- Obtain top management’s endorsement and participation. The company’s top executives should publicly endorse the programme and confirm its value by actually participating in some of the activities.

- Collaborate with other organizations. Wherever possible, achieve economies of scale by joining forces with other local organizations, using community facilities, etc.

- Keep personal information confidential. Make a point of keeping personal information about health problems, test results and even participation in particular activities out of personnel files and obviate potential stigmatization by keeping it confidential.

- Give the programme a positive theme and keep changing it. Give the programme a high profile and publicize its objectives widely. Without dropping any useful activities, change the programme’s emphasis to generate new interest and to avoid appearing stagnant. One way to accomplish this is to “piggy back” on national and community programmes such as National Heart Month and Diabetes Week in the United States.

- Make it easy to be involved. Activities that cannot be accommodated at the worksite should be located at convenient locations nearby in the community. When it is not feasible to schedule them during working hours, they may be held during the lunch hour or at the end of a work shift; for some activities, evenings or weekends may be more convenient.

- Consider offering incentives and awards. Commonly used incentives to encourage programme participation and recognize achievements include released time, partial or 100% rebates of any fees, reduction in employee’s contribution to group health insurance plan premiums (“risk-rated” health insurance), gift certificates from local merchants, modest prizes such as T-shirts, inexpensive watches or jewelry, use of a preferred parking space, and recognition in company newsletters or on worksite bulletin boards.

- Evaluate the programme. The numbers of participants and their drop-out rates will demonstrate the acceptability of particular activities. Measurable changes such as smoking cessation, loss or gain of weight, lower levels of blood pressure or cholesterol, indices of physical fitness, etc., can be used to appraise their effectiveness. Periodic employee surveys can be used to assess attitudes toward the programme and elicit suggestions for improvement. And review of such data as absenteeism, turnover, appraisal of changes in quantity and quality of production, and utilization of health care benefits may demonstrate the value of the programme to the organization.

Conclusion

Although there are significant challenges to be overcome, they are not insurmountable. Health promotion programs may be no less, and sometimes even more, valuable in small organizations than in larger ones. Although valid data are difficult to come by, it may be expected that they will yield similar returns of improvement with regard to employee health, well-being, morale and productivity. To achieve these with resources that are often limited requires careful planning and implementation, the endorsement and support of top executives, the involvement of employees and their representatives, the integration of the health promotion program with the organization’s health and safety policies and practices, a health care insurance plan and appropriate labor-management policies and agreements, and utilization of free or low-cost materials and services available in the community.