There is a common misperception that, outside of reproductive differences, female and male workers will be similarly affected by workplace health hazards and attempts to control them. While women and men do suffer from many of the same disorders, they differ physically, metabolically, hormonally, physiologically and psychologically. For example, women’s smaller average size and muscle mass dictate special attention to the fitting of protective clothing and devices and the availability of properly designed hand tools, while the fact that their body mass is usually smaller than that of men makes them more susceptible, on average, to the effects of alcohol abuse on the liver and the central nervous system.

They also differ in the types of job they hold, in the social and economic circumstances that influence their lifestyles, and in their participation in and response to health promotion activities. Although there have been some recent changes, women are still more likely to be found in jobs that are stultifyingly routine and in which they are exposed to repetitive injury. They suffer from pay inequity and are much more likely than men to be burdened with homemaking responsibilities and the care of children and elderly dependants.

In industrialized countries women have a longer life expectancy than men; this applies to every age group. At age 45, a Japanese woman may expect to live on average another 37.5 years, and a 45-year-old Scottish woman another 32.8 years, with women from most of the other countries of the developed world falling between these limits. These facts lead to an assumption that women are, therefore, healthy. There is a lack of awareness that these “extra” years are frequently marred by chronic illness and disability much of which is preventable. Many women know far too little about the health risks they face and, therefore, about the measures they can take to control those risks and protect themselves against serious disease and injury. For example, many women are rightfully concerned about breast cancer but ignore the fact that heart disease is by far the major cause of death in women and that, owing primarily to the increase in their cigarette smoking—which is also a major risk factor for coronary artery disease—the incidence of lung cancer among women is increasing.

In the United States, a 1993 national survey (Harris et al. 1993), involving interviews of more than 2,500 adult women and 1,000 adult men, confirmed that women suffer from serious health problems and that many do not receive the care they need. Between three and four out of ten women, the survey found, are at risk for undetected treatable disease because they are not receiving appropriate clinical preventive services, largely because they lack health care insurance or because their doctors never suggested that appropriate tests were available and should be sought. Furthermore, a substantial number of the American women surveyed were not happy with their personal physicians: four out of ten (twice the proportion of men) said their physicians “spoke down” to them and 17% (compared to 10% of men) had been told that their symptoms were “all in the head”.

While overall rates of mental illness are roughly the same for men and women, the patterns are different: women suffer more from depression and anxiety disorders while drug and alcohol abuse and antisocial personality disorders are more common among men (Glied and Kofman 1995). Men are more likely to seek and receive care from mental health specialists while women are more often treated by primary care physicians, many of whom lack the interest if not the expertise to treat mental health problems. Women, especially older women, receive a disproportionate share of the prescriptions for psychotropic drugs, so that concern has arisen that these drugs are possibly being overutilized. All too often, difficulties stemming from inordinate levels of stress or from problems that are preventable and treatable are explained away by health professionals, family members, supervisors and co-workers, and even by women themselves, as being reflective of the “time of the month” or “change of life”, and, therefore, go untreated.

These circumstances are compounded by the assumption that women—young and old alike—know all there is to know about their bodies and how they function. This is far from the truth. There exists widespread ignorance and uncritically accepted misinformation. Many women feel ashamed to reveal their lack of knowledge and are being needlessly worried by symptoms that are in fact either “normal” or simply explained.

As women constitute some 50% of the workforce in a large section of the employment arena, and considerably more in some service industries, the consequences of their preventable and correctable health problems levy a significant and avoidable toll on their well-being and productivity and on the organization as well. That toll may be considerably reduced by a worksite health promotion program designed for women.

Worksite Health Promotion for Women

A good deal of health information is provided by newspapers and magazines and on television but much of that is incomplete, sensationalized or geared to the promotion of particular products or services. Too often, in reporting on current medical and scientific advances, the media raise more questions than they answer and even cause needless anxiety. Health care professionals in hospitals, clinics and private offices often fail to make sure that their patients are properly educated about the problems they present, to say nothing of taking the time to inform them about important health issues unrelated to their symptoms.

A properly designed and administered worksite health promotion program should provide accurate and complete information, opportunities to ask questions either in group or individual sessions, clinical preventive services, access to a variety of health promotion activities and counseling about adjustments that may prevent or minimize distress and disability. The worksite offers an ideal venue for the sharing of health experiences and information, particularly when they are relevant to circumstances encountered on the job. One can also take advantage of the peer pressure that is present in the workplace to provide workers with additional motivation for participating and persisting in health promoting activities and in maintaining a healthful lifestyle.

There is a variety of approaches to programming for women. Ernst and Young, the large accounting firm, offered its London employees a series of Health Seminars for Women conducted by an outside consultant. They were attended by all grades of staff and were well received. The women who attended were secure in the format of the presentations. As an outsider, the consultant posed no threat to their employment status, and together they cleared up many areas of confusion about women’s health.

Marks and Spencer, a major retailer in the United Kingdom, conducts a program through its in-house medical department using outside resources to provide services to employees in their many regional worksites. They offer screening examinations and individual advice to all their staff, together with an extensive range of health literature and videotapes, many of which are produced in-house.

Many companies use independent health advisers outside the company. An example in the United Kingdom is the service provided by the BUPA (British United Provident Association) Medical Centers, who see many thousands of women through their network of 35 integrated but geographically scattered units, supplemented by their mobile units. Most of these women are referred through their employers’ health promotion programs; the remainder come independently.

BUPA was probably the first, at least in the United Kingdom, to establish a women’s health centre dedicated to preventive services exclusively for women. Hospital-based and free-standing women’s health centers are becoming more common and are proving attractive to women who have not been well served by the prevailing health care system. In addition to providing prenatal and obstetrical care, they tend to offer broad-ranging primary care, with most placing particular emphasis on preventive services.

The National Survey of Women’s Health Centers, conducted in 1994 by researchers from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health with support from the Commonwealth Foundation (Weisman 1995), estimated that there are 3,600 women’s health centers in the United States, of which 71% are reproductive health centers providing primarily routine outpatient gynaecological examinations, Pap tests and family planning services. They also provide pregnancy tests, abortion counseling (82%) and abortions (50%), screening and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, breast examinations and blood pressure checks.

Twelve per cent are primary care centers (these include women’s college health services) which provide basic well-woman and preventive care including periodic physical examinations, routine gynaecological examinations and Pap tests, diagnosis and treatment of menstrual problems, menopausal counseling and hormone replacement therapy, and mental health services, including drug and alcohol abuse counseling and treatment.

Breast centers constitute 6% of the total (see below), while the remainder are centers providing various combinations of services. Many of these centers have demonstrated interest in contracting to provide services to female employees of nearby organizations as part of their worksite health promotion programs.

Regardless of the venue, the success of worksite health promotion programming for women hinges not only on the reliability of the information and services offered but, more important, on the manner in which they are presented. The programs must be sensitized to women’s attitudes and aspirations as well as to their concerns and, while being supportive, they should be free of the condescension with which these problems are so often addressed.

The remainder of this article will focus on three categories of problems regarded as particularly important health concerns for women—menstrual disorders, cervical and breast cancer and osteoporosis. However, in addressing other health categories, the worksite health promotion program should ensure that any other problems of particular relevance for women will not be overlooked.

Menstrual Disorders

For the great majority of women, menstruation is a “natural” process that presents few difficulties. The menstrual cycle may be disturbed by a variety of conditions which may cause discomfort or concern for the employee. These may lead her to take sick absence on a regular basis, often reporting a “cold” or “sore throat” rather than a menstrual problem, especially if the absence certificate is to be submitted to a male manager. However, the absence pattern is obvious and referral to a qualified health professional may resolve the problem rapidly. Menstrual problems that may affect the workplace include amenorrhoea, menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea, the premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and menopause.

Amenorrhoea

While amenorrhoea may create concern, it does not ordinarily affect work performance. The most common cause of amenorrhoea in younger women is pregnancy and in older women it is menopause or a hysterectomy. However, it may also be attributable to the following circumstances:

- Poor nutrition or underweight. The reason for poor nutrition may be socioeconomic in that little food is available or affordable, but it may also be the result of self-starvation related to eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

- Excessive exercise. In many developed countries. women train excessively in physical fitness or sports programmes. Even though their food intake may be adequate, they may have amenorrhoea.

- Medical conditions. Problems arising from hypothyroidism or other endocrine disorders, tuberculosis, anaemia from any cause and certain serious, life-threatening diseases can all cause amenorrhoea.

- Contraceptive measures. Medications containing progesterone only will commonly lead to amenorrhoea. It should be noted that sterilization without цphorectomy does not cause a woman’s periods to stop.

Menorrhagia

In the absence of any objective measure of menstrual flow, it is commonly accepted that any flow of menses which is heavy enough to interfere with a woman’s normal day-to-day activities, or which leads to anemia, is excessive. When the flow is heavy enough to overwhelm the normal circulating anti-clotting factor, the woman with “heavy periods” may complain of passing clots. Inability to control the blood flow by any normal sanitary protection can lead to considerable embarrassment in the workplace and may lead to a pattern of regular, monthly one- or two-day absences.

Menorrhagia may be caused by uterine fibroids or polyps. It can also be caused by an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) and, rarely, it may be the first indication of a severe anemia or other serious blood disorder such as leukaemia.

Dysmenorrhoea

Although the vast majority of menstruating women experience some discomfort at the time of menstruation, only a few have pain sufficient to interfere with normal activity and, thus, require referral for medical attention. Again, this problem may be suggested by a pattern of regular monthly absences. Such difficulties associated with menstruation may for certain practical purposes be classified thus:

- Primary dysmenorrhoea. Young women with no evidence of disease may suffer pain on the day before or on the first day of their period that is serious enough to induce them to take time off from work. Although no cause has been found, it is known to be associated with ovulation and, hence, can be prevented by the oral contraceptive pill or by other medication which prevents ovulation.

- Secondary dysmenorrhoea. The onset of painful periods in a woman in her middle thirties or later suggests pelvic pathology and should be fully investigated by a gynaecologist.

It should be noted that some over-the-counter or prescribed analgesics taken for dysmenorrhoea may cause drowsiness and can present a problem for women working in jobs that require alertness to occupational hazards.

Premenstrual syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a combination of physical and psychological symptoms experienced by a relatively small percentage of women during the seven or ten days prior to menstruation, has developed its own mythology. It has falsely been credited as the cause of women’s so-called emotionalism and “flightiness”. According to some men, all women suffer from it, while ardent feminists claim that no women have it. In the workplace, it has improperly been cited as a rationale for keeping women out of positions requiring decision making and the exercise of judgment, and it has served as a convenient excuse for denying women promotion to managerial and executive levels. It has been blamed for women’s problems with interpersonal relations and, indeed, in England it has provided the grounds for pleas of temporary insanity that enabled two separate female defendants to escape charges of murder.

The physical symptoms of PMS may include abdominal distention, breast tenderness, constipation, sleeplessness, weight gain due to increased appetite or to sodium and fluid retention, fine-movement clumsiness and inaccuracy in judgment. The emotional symptoms include excessive crying, temper tantrums, depression, difficulty in making decisions, an inability to cope in general and a lack of confidence. They always occur in the premenstrual days, and are always relieved by the onset of the period. Women taking the combined oral contraceptive pill and those who have had oophorectomies rarely get PMS.

The diagnosis of PMS is based on the history of its temporal relationship to menstrual periods; in the absence of definitive causes, there are no diagnostic tests. Its treatment, the intensity of which is determined by the intensity of the symptoms and their effect on normal activities, is empirical. Most cases respond to simple self-help measures which include abolishing caffeine from the diet (tea, coffee, chocolate and most cola soft drinks all contain significant amounts of caffeine), frequent small feedings to minimize any tendency to hypoglycemia, restricting sodium intake to minimize fluid retention and weight gain, and regular moderate exercise. When these fail to control the symptoms, physicians may prescribe mild diuretics (for two to three days only) that control sodium and fluid retention and/or oral hormones that modify ovulation and the menstrual cycle. In general, PMS is treatable and should not represent a significant problem to women in the workplace.

Menopause

Menopause reflecting ovarian failure may occur in women in their thirties or may be postponed to well beyond the age of 50; by the age of 48, about half of all women will have experienced it. The actual time of the menopause is influenced by general health, nutrition and familial factors.

The symptoms of the menopause are diminished frequency of periods usually coupled with scanty menstrual flow, hot flushes with or without night sweats, and a diminution in vaginal secretions, which may cause pain during sexual intercourse. Other symptoms frequently attributed to the menopause include depression, anxiety, tearfulness, lack of confidence, headaches, changes in skin texture, loss of sexual interest, urinary difficulties and sleeplessness. Interestingly, a controlled study involving a symptom questionnaire administered to both men and women showed that a significant portion of these complaints were shared by men of the same age (Bungay, Vessey and McPherson 1980).

The menopause, coming as it does at about the age of 50, may coincide with what has been called the “mid-life transition” or the “mid-life crisis”, terms coined to denote collectively the experiences which seem to be shared by both men and women in their middle years (if anything, they appear to be more common among men). These include loss of purpose, dissatisfaction with one’s job and with life in general, depression, waning interest in sexual activity and a tendency to diminished social contacts. It may be precipitated by the loss of spouse or partner through separation or death or, as regards one’s job, by failure to win an expected promotion or by separation, whether by termination or voluntary retirement. In contrast to menopause, there is no known hormonal basis for the mid-life transition.

Particularly in women, this period may be associated with the “empty nest syndrome,” the sense of purposelessness that may be felt when, their children having left the home, their whole perceived raison d’être seems to have been lost. In such cases, the job and the social contacts in the workplace often provide a stabilizing, therapeutic influence.

Like many of the other “female problems,” menopause has developed its own mythology. Preparatory education debunking these myths supplemented by sensitive supportive counseling will go far to preventing significant dislocations. Continuing to work and maintaining her satisfactory performance on the job may be of crucial value in sustaining a woman’s well-being at this time.

It is at this point that the advisability of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) needs to be considered. Currently the subject of some controversy, HRT was originally prescribed to control menopausal symptoms if they became excessively severe. While usually effective, the hormones commonly used often precipitated vaginal bleeding and, more important, they were suspected of being carcinogenic. As a result, they were prescribed only for limited periods of time, just long enough to control the troublesome menopausal symptoms.

HRT has no effect on the symptoms of the mid-life transition. However, if a woman’s flushes are controlled and she can get a good night’s sleep because her night sweats are prevented, or if she can respond to lovemaking more enthusiastically because it is no longer painful, then some of her other problems may be resolved.

Today, the value of long-term HRT is increasingly being recognized in maintaining the integrity of bone in women with osteoporosis (see below) and in reducing the risk of coronary heart disease, now the highest-ranking cause of death among women in industrialized countries. Newer hormones, combinations and sequences of administration may eliminate the occurrence of planned vaginal bleeding and there appears to be little or no risk of carcinogenesis, even among women with a history of cancer. However, because many physicians are strongly biased for or against HRT, women need to be educated about its benefits and disadvantages so that they can participate confidently in the decision about whether to use it or not.

Recently, calling to mind the millions of women “baby boomers” (children born after the Second World War) who will be reaching the age of menopause within the next decade, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) warned that staggering increases in osteoporosis and heart disease could result unless women are better educated about menopause and the interventions designed to prevent disease and disability and to prolong and enhance their lives after menopause (Voelker 1995). ACOG president William C. Andrews, MD, has proposed a three-pronged program that includes a massive campaign to educate physicians about the menopause, a “perimenopausal visit” to a physician by all women over the age of 45 for a personal risk assessment and in-depth counseling, and involvement of the news media in educating women and their families about the symptoms of menopause and the benefits and risks of treatments like HRT before women reach menopause. The worksite health promotion program can make a major contribution to such an educational effort.

Screening for Cervical and Breast Disease

With regard to women’s needs, a health promotion program should either provide or, at least, recommend periodic screening for cervical and breast cancer.

Cervical disease

Regular screening for precancerous cervical changes by means of the Pap test is a well-established practice. In many organizations, it is made available in the workplace or in a mobile unit brought to it, eliminating the need for female employees to spend time traveling to a facility in the community or visiting their personal physicians. The services of a physician are not required in the administration of this procedure: satisfactory smears may be taken by a well-trained nurse or technician. More important is the quality of the reading of the smears and the integrity of the procedures for record-keeping and reporting of the results.

Breast cancer

Although breast screening by mammography is widely practiced in almost all developed countries, it has been established on a national basis only within the United Kingdom. Currently, over a million women in the United Kingdom are screened, with each woman aged 50 to 64 having a mammogram every three years. All the examinations, including any further diagnostic studies needed to clarify abnormalities in the initial films, are free of charge to the participants. The response to the offer of this three-year cycle of mammography has been over 70%. Reports for the 1993-1994 period (Patnick 1995) show a rate of 5.5% for referral to further assessment; 5.5 women per 1,000 women screened were discovered to have breast cancer. The positive predictive value for surgical biopsy was 70% in this program, compared to some 10% in programs reported elsewhere in the world.

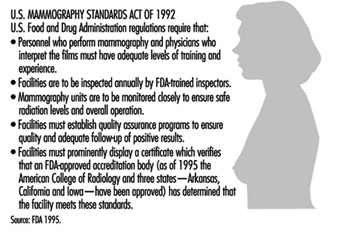

The critical issues in mammography are the quality of the procedure, with particular emphasis on minimizing radiation exposure, and the accuracy of the interpretation of the films. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has promulgated a set of quality regulations proposed by the American College of Radiology that, commencing October 1, 1994, must be observed by the more than 10,000 medical units taking or interpreting mammograms around the country (Charafin 1994). In accordance with the national Mammography Standards Act (enacted in 1992), all mammography facilities in the United States (except those operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs, which is developing its own standards) had to be certified by the FDA as of this date. These regulations are summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1. Mammography quality standards in the United States.

A recent phenomenon in the United States is the increase in the number of breast or breast health centers, 76% of which have appeared since 1985 (Weisman 1995). They are predominantly hospital-affiliated (82%); the others are primarily profit-making enterprises owned by physician groups. About a fifth maintain mobile units. They provide outpatient screening and diagnostic services including physical breast examinations, screening and diagnostic mammography, breast ultrasound, fine-needle biopsy and instruction in breast self-examination. Slightly more than one-third also offer treatment for breast cancer. While primarily focused on attracting self-referrals and referrals by community physicians, many of these centers are making an effort to contract with employer- or labor union-sponsored health promotion programs to provide breast screening services to their female participants.

Introducing such screening programs into the workplace can generate considerable anxiety among some women, particularly those with personal or family histories of cancer and those found to have “abnormal” (or inconclusive) results. The possibility of such non-negative results should be carefully explained in presenting the program, along with the assurance that arrangements are in place for the additional examinations needed to explain and to act upon them. Supervisors should be educated to sanction absences by these women when the necessary follow-up procedures cannot be expeditiously arranged outside of working hours.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disorder, much more prevalent in women than in men, that is characterized by a gradual decline in bone mass leading to susceptibility to fractures which may result from seemingly innocuous movements and accidents. It represents an important public health problem in most developed countries.

The most common sites for fractures are the vertebrae, the distal portion of the radius and the upper portion of the femur. All fractures at these sites in older individuals should cause one to suspect osteoporosis as a contributing cause.

While such fractures usually occur later in life, after the individual has left the workforce, osteoporosis is a desirable target for worksite health promotion programs for a number of reasons: (1) the fractures may involve retirees and add significantly to their medical care costs, for which the employer may be responsible; (2) the fractures may involve the elderly parents or in-laws of current employees, creating a dependant-care burden that can compromise their attendance and work performance; and (3) the workplace presents an opportunity to educate younger people about the eventual danger of osteoporosis and to urge them to initiate the lifestyle changes that can slow its progress.

There are two types of primary osteoporosis:

- Post-menopausal, which is related to loss of oestrogens and, hence, is more prevalent in women than in men (ratio = 6:1). It is commonly found in the 50-to-70 age group and is associated with vertebral fractures and Colles fractures (of the wrist).

- Involutional, which occurs mainly in those over the age of 70 and is only twice as common among women than in men. It is thought to be due to age-related changes in vitamin D synthesis and is associated chiefly with vertebral and femoral fractures.

Both types may be present simultaneously in women. In addition, in a small percentage of cases, osteoporosis has been attributed to a variety of secondary causes including: hyperparathyroidism; the use of corticosteroids, L-thyroxine, aluminum-containing antacids and other drugs; prolonged bed rest; diabetes mellitus; the use of alcohol and tobacco; and rheumatoid arthritis.

Osteoporosis may be present for years and even decades before fractures result. It can be detected by well-standardized x-ray measurements of bone density, calibrated for age and sex, and supplemented by laboratory evaluation of calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Unusual radiolucency of bone in conventional x rays may be suggestive, but such osteopenia usually cannot be reliably detected until more than 30% of the bone is lost.

It is generally agreed that screening asymptomatic individuals for osteoporosis should not be employed as a routine procedure, especially in worksite health promotion programs. It is costly, not very reliable except in the most well-staffed facilities, involves exposure to radiation and, most important, does not identify those women with osteoporosis who are most likely to have fractures.

Accordingly, although everyone is subject to some degree of bone loss, the prevention program for osteoporosis is focused on those individuals who are at higher risk for its more rapid progression and who are therefore more susceptible to fractures. A special problem is that although the earlier in life the preventive measures are started, the more effective they are, it is nonetheless difficult to motivate younger people to adopt lifestyle changes in the hope of avoiding a health problem that may develop at what many of them consider to be a very remote age of life. A saving grace is that many of the recommended changes are also useful in the prevention of other problems as well as in promoting general health and well-being.

Some risk factors for osteoporosis cannot be changed. They include:

- Race. On average, Whites and Orientals have lower bone density than Blacks matched age for age and are therefore at greater risk.

- Sex. Women have less dense bones than men when matched for age and race and therefore are at greater risk.

- Age. All people lose bone mass with age. The stronger the bones are in youth, the less likely is it that the loss will reach potentially dangerous levels in old age.

- Family history. There is some evidence of a genetic component in the attainment of peak bone mass and the rate of subsequent bone loss; thus, a family history of suggestive fractures in family members may represent an important risk factor.

The fact that these risk factors cannot be altered makes it important to give attention to those that can be modified. Among the measures that may be taken to delay the onset of osteoporosis or to diminish its severity, the following may be mentioned:

- Diet. If adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D are not present in the diet, supplementation is recommended. This is particularly important for people with lactose intolerance who tend to avoid milk and milk products, the major sources of dietary calcium, and is most effective if maintained from childhood until the thirties as peak bone density is being achieved. Calcium carbonate, the most commonly used form of calcium supplementation, frequently causes side effects such as constipation, rebound hyperacidity, abdominal bloating and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Accordingly, many people substitute preparations of calcium citrate which, despite a significantly lower content of elemental calcium, is better absorbed and has fewer side-effects. The amounts of vitamin D present in the usual multivitamin preparation suffice for slowing the bone loss of osteoporosis. Women should be cautioned against excessive doses, which may lead to hypervitaminosis D, a syndrome that includes acute renal failure and increased resorption of bone.

- Exercise. Regular moderate weight-bearing exercise-for example, 45 to 60 minutes of walking at least three times a week-is advisable.

- Smoking. Women who smoke have their menopause on average two years earlier than non-smokers. Without hormone replacement, the earlier menopause will accelerate post-menopausal bone loss. This is another important reason to counter the current trend to increased cigarette smoking among women.

- Hormone replacement therapy. If oestrogen replacement is undertaken, it should be started early in the progress of the menopausal changes since the rate of bone loss is greatest during the first few years after menopause. Because bone loss is resumed after the discontinuation of oestrogen therapy, it should be maintained indefinitely.

Once osteoporosis is diagnosed, treatment is aimed at circumventing further bone loss by following all of the above recommendations. Some recommend using calcitonin, which has been shown to increase total body calcium. However, it must be given parenterally; it is expensive; and there is yet no evidence that it retards or reverses the loss of calcium in the bone or reduces the occurrence of fractures. Biphosphonates are gaining ground as anti-resorptive agents.

It must be remembered that osteoporosis sets the stage for fractures but it does not cause them. Fractures are caused by falls or sudden injudicious movements. While the prevention of falls should be an integral part of every worksite safety program, it is particularly important for individuals who may have osteoporosis. Thus, the health promotion program should include education about safeguarding the environment in both the workplace and in the home (e.g., eliminating or taping down trailing electrical wires, painting the edges of steps or irregularities in the floor, tacking down slippery rugs and promptly drying up any wet spots) as well as sensitizing individuals to such hazards as insecure footwear and seats that are difficult to get out of because they are too low or too soft.

Women’s Health and Their Work

Women are in the paid workforce to stay. In fact, they are the mainstay of many industries. They should be treated as equal to men in every respect; only some aspects of their health experience are different. The health promotion program should inform women about these differences and empower them to seek the kind and quality of health care they need and deserve. Organizations and those who manage them should be educated to understand that most women do not suffer from the problems described in this article, and that, for the small proportion of women who do, prevention or control is possible. Except in rare instances, no more frequent than among men with similar health problems, these problems do not constitute barriers to good attendance and effective work performance.

Many women managers get to their high positions not only because their work is excellent, but because they experience none of the problems of female health that have been outlined above. This can make some of them intolerant and unsupportive of other women who do have such difficulties. One major area of resistance to women’s status in the workplace, it appears, can be women themselves.

A worksite health promotion program that embodies a focus on women’s health issues and problems and addresses them with appropriate sensitivity and integrity can have an important positive impact for good, not only for the women in the workforce, but also for their families, the community and, most important, the organization.