This case study describes the mammography program at Marks and Spencer, the first to be offered by an employer on a nationwide scale. Marks and Spencer is an international retail operation with 612 stores worldwide, the majority being in the United Kingdom, Europe and Canada. In addition to a number of international franchise operations, the company owns Brooks Brothers and Kings Super Markets in the United States and D’Allaird’s in Canada and pursues extensive financial activities.

The company employs 62,000 people, the majority of whom work in 285 stores in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. The company’s reputation as a good employer is legendary and its policy of good human relations with staff has included the provision of comprehensive, high-quality health and welfare programs.

Although a treatment service is provided at some work locations, this need is largely met by community-based primary care physicians. The company health policy emphasizes the early detection and prevention of disease. A number of innovative screening programs have consequently been developed over the past 20 years, many of which have predated similar projects in the National Health Service (NHS). Over 80% of the workforce is female, a fact that has influenced the choice of screening programs, which include cervical cytology, ovarian cancer screening and mammography.

Breast Cancer Screening

In the mid-1970s the New York HIP study (Shapiro 1977) proved that mammography was capable of detecting impalpable breast cancers with the expectation that earlier detection would reduce mortality. To an employer of large numbers of middle-aged women, the appeal of mammography was obvious and a screening program was introduced in 1976 (Hutchinson and Tucker 1984; Haslehurst 1986). At that time there was virtually no access to reliable high-quality mammography in the public sector and that available in private health care organizations was of variable quality and expensive. The first task therefore was to ensure access to a uniformly high quality and this challenge was met by using mobile screening units, each equipped with a waiting area, examination cubicle and mammography equipment.

Centralized administration and film processing allowed continuous checks on all aspects of quality and allowed film interpretation to be undertaken by an experienced group of mammographers. There was, however, a disadvantage in that the radiographer was not able to immediately examine the developed film to verify that there were no technical errors so that if there had been any, the employee could be recalled or other arrangements made for the necessary repeat examination.

Compliance has always been exceptionally high and has remained over 80% for all age groups. Doubtless this is due peer group pressure, the easy availability of the service at or near the worksite and, until recently, a lack of mammography facilities in the NHS.

Women are invited to join the screening program and attendance is entirely voluntary. Prior to screening, short educational sessions are carried out by the company doctor or nurse, both of whom are available to answer queries and give explanations. Common anxieties include concern about radiation dosage and worry that the compression of the breast may cause pain. Women who are recalled for further tests are seen during working hours and fully recompensed for travel expenses for themselves and a companion.

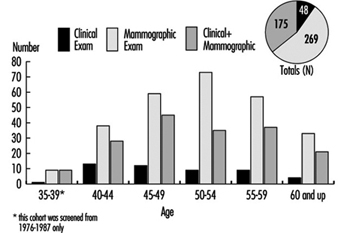

Three modalities were used for the first five years of the program: clinical examination by a highly trained nurse-practitioner, thermography and mammography. Thermography was a time-consuming examination with a high rate of false positives and made no contribution to the cancer detection rate; accordingly it was discontinued in 1981. Although of limited value in cancer detection, clinical examination, which includes a detailed review of personal and family history, provides invaluable information to the radiologist and allows the client time to discuss her fears and other health issues with a sympathetic health professional. Mammography is the most sensitive of the three tests. Cranio-caudal and lateral oblique views are taken at the initial examination with single views only at the interval check. Single reading of films is the norm, though double reading is used for difficult cases and as a random quality check. Figure 1 shows the contribution of clinical examination and mammography to the total cancer detection rate. Of the 492 cases of cancer found, 10% were detected by clinical examination alone, 54% by mammography alone, and 36% were noted by clinical examination and mammography.

Figure 1. Screening for breast cancer. Contribution of clinical examination and mammography to cancer detection, by age group.

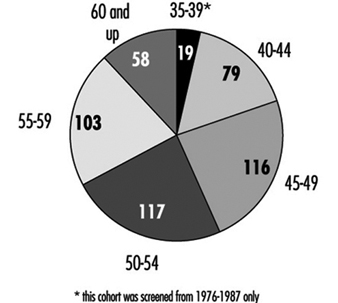

Women aged 35 to 70 were offered screening when the program was first introduced but the low cancer detection rate and high incidence of benign breast disease among those in the 35 to 39 age group led to withdrawal of the service in 1987 from these women. Figure 19 shows the numbers of screen-detected cancers by age group.

Figure 2. Age distribution of screen-detected cancers.

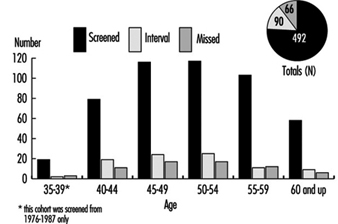

Similarly, the screening interval has changed from a yearly interval (reflecting initial enthusiasm) to a two-year gap. Figure 3 shows the number of screen-detected cancers by age group with the corresponding numbers of interval tumors and missed tumors. Interval cases are defined as those occurring after a truly negative screen during the time between routine tests. Missed cases are defined as those cancers which can be seen retrospectively on the films but were not identified at the time of the screening test.

Figure 3. Number of screen-detected cancers, interval cancers and missed cancers, by age group.

Among the screened population, 76% of breast cancers were detected at screening with a further 14% of cases occurring during the interval between examinations. The interval cancer rate will be carefully monitored to ensure that it does not rise to an unacceptably high level.

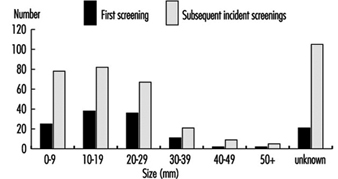

The survival benefit of screening women under the age of 50 remains unproven although it is agreed that smaller cancers are detected and this allows some women to choose between mastectomy or breast conservation therapy—a choice valued highly by many. Figure 4 shows the sizes of screen-detected cancers, the majority being under two centimeters in size and node negative.

Figure 4. Sizes of screen-detected cancers.

Impact of the Forrest Report

In the late 1980s, Professor Sir Patrick Forrest recommended that regular breast screening be made available to women over the age of 50 via the NHS (i.e., with no charge at the point of delivery of the service) (Forrest 1987). His most important recommendation was that the service should not start until specialist staff had been fully trained in the multidisciplinary approach to breast care diagnosis. Such staff was to include radiologists, nurse counselors and breast physicians. Since 1990, the United Kingdom has had an outstanding breast screening and assessment service for women over 50.

Coincidentally with this national development, Marks and Spencer reviewed its data and a major flaw in the program became apparent. The recall rate following routine screening was in excess of 8% for women over fifty and 12% for younger women. Analysis of the data showed that common reasons for recall were technical problems, such as malpositioning, processing errors, difficulties with grid lines or a need for further views. Additionally, it was clear that the use of ultrasonography, specialized mammography and fine needle aspiration cytology could cut the recall and referral rate even further. An initial study confirmed these impressions, and it was decided to redefine the screening protocol so that clients who needed further tests were not referred back to their family practitioners, but were retained within the screening program until a definitive diagnosis was made. Most of these women were returned to a schedule of routine recall after the further investigations and this reduced the formal surgical referral rate to a minimum.

Instead of duplicating the service provided by the National Health Service, a policy of partnership was developed which allowed Marks and Spencer to draw upon the expertise of the public sector while company funding is used to improve service for all. The breast screening program is now delivered by a number of providers: about half the requirement is met by the original mobile service but employees at the larger city stores now receive routine screening at specialist centers, which may either be in the private or public sectors. This cooperation with the National Health Service has been an exciting and challenging development and has helped to improve the overall standards of breast diagnosis and care for the entire population. By marrying together both private worksite and public sector programs it is possible to deliver an exceptionally high quality service to a widely distributed population.