In this era of multinational organizations and ever-expanding international trade, employees are being increasingly called upon to undertake travel for business reasons. At the same time, more employees and their families are spending their holidays in travel to distant places around the world. While for most people such travel is usually exciting and enjoyable, it is often burdensome and debilitating and, especially for those who are not properly prepared, it can be hazardous. Although life-threatening situations may conceivably be encountered, most of the problems associated with travel are not serious. For the holiday traveller, they bring anxiety, discomfort and inconvenience along with the disappointment and added expense involved in shortening a trip and making new travel arrangements. For the business person, travel difficulties may ultimately affect the organization adversely on account of the impairment of his or her work performance in negotiations and other dealings, to say nothing of the cost of having to abort the mission and sending someone else to complete it.

This article will outline a comprehensive travel protection programme for individuals making short-term business trips and it will briefly describe steps that may be taken to circumvent the more frequently encountered travel hazards. (The reader may consult other sources—e.g., Karpilow 1991—for information on programmes for individuals on long-term expatriate assignments and on programmes for whole units or groups of employees dispatched to workstations in distant locales).

A Comprehensive Travel Protection Programme

Occasional seminars on managing the hazards of travel are a feature of many worksite health promotion programmes, especially in organizations where a sizeable proportion of employees travels extensively. In such organizations, there often is an in-house travel department which may be given the responsibility of arranging the sessions and procuring the pamphlets and other literature that may be distributed. For the most part, however, educating the prospective traveller and providing any services that may be needed are conducted on an individual rather than a group basis

Ideally, this task is assigned to the medical department or employees’ health unit, where, it is to be hoped, a knowledgeable medical director or other health professional will be available. The advantages of maintaining in-house medical unit staff, apart from convenience, is their knowledge of the organization, its policies and its people; the opportunity for close collaboration with other departments that may be involved (personnel and travel, for example); access to medical records containing health histories of those assigned to travel assignments, including details of any prior travel misadventures; and, at least, a general knowledge of the kind and intensity of work to be accomplished during the trip.

Where such an in-house unit is lacking, the travelling individual may be referred to one of the “travel clinics” that are maintained by many hospitals and private medical groups in the community. The advantages of such clinics include medical staff specializing in the prevention and treatment of the diseases of travellers, current information about conditions in the areas to be visited and fresh supplies of any vaccines that may be indicated.

A number of elements should be included if the travel protection programme is to be truly comprehensive. These are considered under the following heads.

An established policy

Too often, even when a trip has been scheduled for some time, the desired steps to protect the traveller are taken on an ad hoc, last-minute basis or, sometimes, neglected entirely. Accordingly, an established written policy is a key element in any travel protection programme. Since many business travellers are high-level executives, this policy should be promulgated and supported by the chief executive of the organization so that its provisions can be enforced by all of the departments involved in travel assignments and arrangements, which may be headed by managers of lower rank. In some organizations, the policy expressly prohibits any business trip if the traveler has not received a medical “clearance”. Some policies are so detailed that they designate minimal height and weight criteria for authorizing the booking of more expensive business-class seating instead of the much more crowded seats in the economy or tourist sections of commercial aircraft, and specify the circumstances under which a spouse or family members may accompany the traveller.

Planning the trip

The medical director or responsible health professional should be involved in planning the itinerary in conjunction with the travel agent and the individual to whom the traveller reports. The considerations to be addressed include (1) the importance of the mission and its ramifications (including obligatory social activities), (2) the exigencies of travel and conditions in the parts of the world to be visited, and (3) the physical and mental condition of the traveller along with his or her capacity to withstand the rigours of the experience and continue to perform adequately. Ideally, the traveller will also be involved in such decisions as to whether the trip should be postponed or cancelled, whether the itinerary should be shortened or otherwise modified, whether the mission (i.e., with respect to number of people visited or number or duration of meetings, etc.) should be modified, whether the traveller should be accompanied by an aide or assistant, and whether periods of rest and relaxation should be built into the itinerary.

Pre-travel medical consultation

If a routine periodic medical examination has not been performed recently, a general physical examination and routine laboratory tests, including an electrocardiogram, should be performed. The purpose is to ensure that the employee’s health will not be adversely affected either by the rigours of transit per se or by other circumstances encountered during the trip. The status of any chronic diseases needs to be determined and modifications advised for those with such conditions as diabetes, autoimmune diseases or pregnancy. A written report of the findings and recommendations should be prepared to be made available to any physicians consulted for problems arising en route. This examination also provides a baseline for evaluating potential illness when the traveller returns.

The consultation should include a discussion of the desirability of immunizations, including a review of their potential side-effects and the differences between those that are required and those that are only recommended. An inoculation schedule individualized for the traveler’s needs and departure date should be developed and the necessary vaccines administered.

Any medications being taken by the traveller should be reviewed and prescriptions provided for adequate supplies, including allowances for spoilage or loss. Modifications of timing and dosage must be prepared for travellers crossing several time zones (e.g., for those with insulin-dependent diabetes). Based on the work assignment and mode of transport, medications should be prescribed for the prevention of certain specific diseases, including (but not limited to) malaria, traveller’s diarrhoea, jet lag and high altitude sickness. In addition, medications should be prescribed or supplied for on-the-trip treatment of minor illnesses such as upper respiratory infections (particularly nasal congestion and sinusitis), bronchitis, motion sickness, dermatitis and other conditions that may be reasonably anticipated.

Medical kits

For the traveller who does not wish to spend valuable time searching for a pharmacy in case of need, a kit of medications and supplies may be invaluable. Even if the traveller may be able to find a pharmacy, the pharmacist’s knowledge of the traveller’s special condition may be limited, and any language barrier may result in serious lapses in communication. Further, the medication offerred may not be safe and effective. Many countries do not have strict drug labelling laws and quality assurance regulations are sometimes non-existent. The expiration dates of medications are often ignored by small pharmacies and the high temperatures in tropical climates may inactivate certain medications that are stored on shelves in hot shops.

While commercial kits stocked with routine medications are available, the contents of any such kit should be customized to meet the traveller’s specific needs. Among those most likely to be needed, in addition to medications prescribed for specific health problems, are drugs for motion sickness, nasal congestion, allergies, insomnia and anxiety; analgesics, antacids and laxatives, as well as medication for haemorrhoids, menstrual discomfort and nocturnal muscle cramps. The kit may furthermore contain antiseptics, bandages and other surgical supplies.

Travellers should carry either letters signed by a physician on letterhead stationery or else prescription blanks listing the medications being carried and indicating the conditions for which they have been prescribed. This may save the traveller from embarrassing and potentially long delays at international ports of entry where customs agents are especially diligent in looking for illicit drugs.

The traveller should also carry either an extra pair of eyeglasses or contact lenses with adequate supplies of cleansing solutions and other necessary appurtenances. (Those going to excessively dirty or dusty areas should be encouraged to wear eyeglasses rather than contact lenses). A copy of the user’s lens prescription will facilitate the procurement of replacement glasses should the traveller’s pair be lost or damaged.

Those who travel frequently should have their kits checked before each trip to make sure that the contents have been adjusted to the particular itinerary and are not outdated.

Medical records

In addition to notes confirming the appropriateness of the medications being carried, the traveller should carry a card or letter summarizing any significant medical history, findings on his or her pre-travel health assessment and copies of a recent electrocardiogram and any relevant laboratory data. A record of the traveller’s most recent immunizations may obviate the necessity of submitting to mandatory inoculation at the port of entry. The record should also contain the name, address, telephone and fax numbers of a physician who can supply additional information about the traveller should it be required (a Medic-Alert type of badge or bracelet can be useful in this regard).

A number of vendors can supply medical record cards with microfilm chips containing travellers’ complete medical files. While often convenient, the foreign physician may lack access to the microfilm viewer or a hand lens powerful enough to read them. There is also the problem of making sure that the information is up-to-date.

Immunizations

Some countries require all arriving travellers to be vaccinated for certain diseases, such as cholera, yellow fever or plague. While the World Health Organization has recommended that only vaccination for yellow fever be required, a number of countries still require cholera immunization. In addition to protecting travellers, the required immunizations are also intended to protect their citizens from diseases that may be carried by travellers.

Recommended immunizations are intended to prevent travellers from contracting endemic diseases. This list is much longer than the “required” list and is enlarging annually as new vaccines are developed to combat new and rapidly advancing diseases. The desirability of a specific vaccine also changes frequently in accord with the amount and virulence of the disease in the particular area. For this reason, current information is essential. This may be obtained from the World Health Organization; from government agencies such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the Canada Health and Welfare Department; or from the Commonwealth Department of Health in Sydney, Australia. Similar information, usually derived from such sources, may be obtained from local voluntary and commercial organizations; it is also available in periodically updated computer software.

Immunizations recommended for all travellers include diphtheria-tetanus, polio, measles (for those born after 1956 and without a physician-documented episode of measles), influenza and hepatitis B (particularly if the work assignment may involve exposure to this hazard).

The amount of time available for departure may influence the immunization schedule and dosage. For example, for the individual who has never been immunized against typhoid, two injections, four weeks apart, should produce the highest antibody titre. If there is not enough time, those who have not been previously inoculated may be given four pills of the newly developed oral vaccine on alternate days; this will be considerably more effective than a single dose of the injected vaccine. The oral vaccine regimen may also be used as a booster for individuals who have previously received the injections.

Health Insurance and Repatriation Coverage

Many national and private health insurance programmes do not cover individuals who receive health services while outside of the specified area. This can cause embarrassment, delays in receiving needed care and high out-of-pocket expenses for individuals who incur injuries or acute illnesses while on a trip. It is prudent, therefore, to verify that the traveller’s current health insurance will cover him or her throughout the trip. If not, procurement of temporary health insurance covering the entire period of the trip should be advised.

Under certain circumstances, particularly in undeveloped areas, lack of adequate modern facilities and concern over the quality of the available care may dictate medical evacuation. The traveller may be returned to his or her home city or, when the distance is too great, to an acceptable urban medical centre en route. A number of companies provide emergency evacuation services around the world; some, however, are available only in more limited areas. Since such situations are usually quite urgent and stressful for all those involved, it is wise to make preliminary stand-by arrangements with a company that serves the areas to be visited and, since such services may be quite expensive, to confirm that they are covered by the traveller’s health insurance programme.

Post-travel Debriefing

A medical consultation soon after return is a desirable follow-up to the trip. It provides for a review of any health problems that may have arisen and the proper treatment of any that may not have entirely cleared up. It also provides for a debriefing on the circumstances encountered en route that can lead to more appropriate recommendations and arrangements if the trip is to be repeated or undertaken by others.

Coping with the Hazards of Travel

Travel almost always entails exposure to health hazards that, at the least, present inconvenience and annoyance and can lead to serious and disabling illnesses or worse. For the most part, they can be circumvented or controlled, but this usually requires a special effort on the part of the traveller. Sensitizing the traveller to recognize them and providing the information and training required to cope with them is the major thrust of the travel protection programme. The following represent some of the hazards most commonly encountered during travel.

Jet lag.

Rapid passage across time zones can disrupt the physiological and psychological rhythms—the circadian rhythms—that regulate the organism’s functions. Known as “jet lag” because it occurs almost exclusively during air travel, it can cause sleep disturbances, malaise, irritability, reduced mental and physical performance, apathy, depression, fatigue, loss of appetite, gastric distress and altered bowel habits. As a rule, it takes several days before a traveller’s rhythms adapt to the new location. Consequently, it is prudent for travellers to book long-distance flights several days prior to the start of important business or social engagements so as to allow themselves a period during which they can recover their energy, alertness and work capacities (this also applies to the return flight). This is particularly important for older travellers, since the effects of jet lag seem to increase with age.

A number of approaches to minimizing jet lag have been employed. Some advocate the “jet lag diet,” alternating feasting and fasting of carbohydrates or high protein foods for three days prior to departure. Others suggest eating a high carbohydrate dinner prior to departure, limiting food intake during the flight to salads, fruit plates and other light dishes, drinking a good deal of fluids before and during the trip (enough on the plane to require the hourly use of the rest room) and avoidance of all alcoholic beverages. Others recommend the use of a head-mounted light that suppresses the secretion of melatonin by the pineal gland, the excess of which has been linked to some of the symptoms of jet lag. More recently, small doses of melatonin in tablet form (1 mg or less—larger doses, popular for other purposes, produce drowsiness) taken on a prescibed schedule several days before and after the trip, have been found useful in minimizing jet lag. While these may be helpful, adequate rest and a relaxed schedule until the readjustment has been completed are most reliable.

Air travel.

In addition to jet lag, travel by air can be difficult for other reasons. Getting to and through the airport can be a source of anxiety and irritation, especially when one has to cope with traffic congestion, heavy or bulky luggage, delayed or cancelled flights and dashing through terminals to make connecting flights. Long periods of confinement in narrow seats with insufficient leg room are not only uncomfortable but may precipitate attacks of phlebitis in the legs. Most passengers in well-maintained modern aircraft will have no difficulty breathing since cabins are pressurized to maintain a simulated altitude below that of 8,000 feet above sea level. Cigarette smoke may be annoying for those seated in or near the smoking sections of planes that have not been designated as smoke-free.

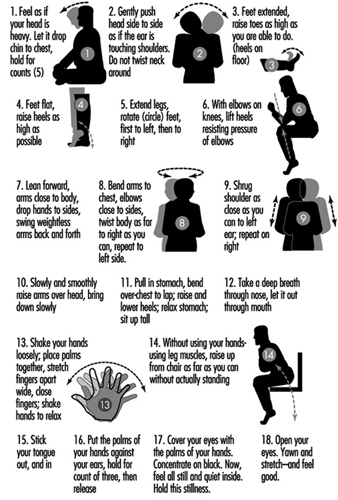

These problems can be minimized by such steps as prearranging transfers to and from the airports and assistance with baggage, providing electric carts or wheel chairs for those for whom the long walk between the terminal entrance and the gate may be troublesome, eating lightly and avoiding alcoholic beverages during the flight, drinking plenty of fluids to combat the tendency toward dehydration and getting out of one’s seat and walking about the cabin frequently. When the lattermost alternative is not feasible, performing stretching and relaxing exercises like those demonstrated in figure 1 is essential. Eye shades may be helpful in trying to sleep during the flight, while wearing ear plugs throughout the flight has been shown to decrease stress and fatigue.

Figure 1. Exercises to be performed during long airplane trips.

In some 25 countries, including Argentina, Australia, India, Kenya, Mexico, Mozambique and New Zealand, arriving aircraft cabins are required to be sprayed with insecticides before passengers are allowed to leave the plane The purpose is to prevent disease-bearing insects from being brought into the country. Sometimes, the spraying is cursory but often it is quite thorough, taking in the entire cabin, including the seated passengers and crew. Travellers who find the hydrocarbons in the spray annoying or irritating should cover their faces with a damp cloth and practice relaxation breathing exercises.

The United States objects to this practice. Transportation Secretary Federico F. Peña has proposed that all airlines and travel agencies be required to notify passengers when they will be sprayed, and the Transportation Department plans to bring this controversial issue before the International Civil Aviation Association and to cosponsor a World Health Organization symposium on this question (Fiorino 1994).

Mosquitoes and other biting pests.

Malaria and other arthropod-borne diseases (e.g., yellow fever, viral encephalitis, dengue fever, filariasis, leishmaniasis, onchocercosis, trypanosomiasis and Lyme disease) are endemic in many parts of the world. Keeping from getting bitten is the first line of defence against these diseases.

Insect repellents containing “DEET” (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) may be used on the skin and/or clothing. Because DEET can be absorbed through the skin and may cause neurological symptoms, preparations with a DEET concentration over 35% are not recommended, especially for infants. Hexanediol is a useful alternative for those who may be sensitive to DEET. Skin-So-Soft®, the commercially available moisturizer, needs to be reapplied every twenty minutes or so to be an effective repellent.

All persons travelling in areas where insect-borne diseases are endemic should wear long-sleeve shirts and long trousers, especially after dusk. In hot climates, wearing loose-fitting thin cotton or linen garments is actually cooler than leaving the skin exposed. Perfumes and scented cosmetics, soaps and lotions that may attract insects should be avoided. Lightweight mesh jackets, hoods and face guards are particularly helpful in highly infested areas. Mosquito bed netting and window screens are important adjuncts. (Before retiring, it is important to spray the inside of the bednetting in case undesirable insects have become trapped in it.)

Protective clothing and nets may be treated with a DEET-containing repellent or with permethrin, an insecticide available in both spray and liquid formulations.

Malaria.

Despite decades of mosquito eradication efforts, malaria remains endemic in most tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Because it is so dangerous and debilitating, the mosquito control efforts described above should be supplemented by prophylactic use of one or more antimalarial drugs. While a number of fairly effective antimalarials have been developed, some strains of the malaria parasite have become highly resistant to some if not all of the currently used drugs. For example, chloroquine, traditionally the most popular, is still effective against strains of malaria in certain parts of the world but is useless in many other areas. Proguanil, mefloquine and doxycycline are currently most commonly used for chloroquine-resistant strains of malaria. Maloprim, fansidar and sulfisoxazole are also used in certain areas. A prophylactic regimen is started prior to entering the malarious area and continued for some time after leaving it.

The choice of the drug is based on “up to the minute” recommendations for the particular areas to be visited by the traveller. The potential side-effects should also be considered: for example, fansidar is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, while mefloquine should not be used by airline pilots or others in whom central nervous system side-effects could impair performance and affect the safety of others, nor by those taking beta-blockers or calcium-channel blockers or other drugs that alter cardiac conduction.

Contaminated water.

Contaminated tap water may be a problem all over the world. Even in modern urban centers, defective pipes and faulty connections in older or poorly maintained buildings may allow the spread of infection. Even bottled water may not be safe, particularly if the plastic seal on the cap is not intact. Carbonated beverages are generally safe to drink provided they have not been allowed to go flat.

Water can be disinfected by heating it to 62ºC for 10 minutes or by adding iodine or chlorine after filtering to remove parasites and worm larvae and then allowing it to stand for 30 minutes.

Water filtration units sold for camping trips are usually not appropriate for areas where the water is suspect since they do not inactivate bacteria and viruses. So-called “Katadyn” filters are available in individual units and filter out organisms larger than 0.2 microns but must be followed by iodine or chlorine treatment to remove viruses. The more recently developed “PUR” filters combine 1.0 micron filters with exposure to a tri-iodine resin matrix that eliminates bacteria, parasites and viruses in a single process.

In areas where the water may be suspect, the traveller should be advised not to use ice or iced drinks and to avoid brushing the teeth with water that has not been purified.

Another important precaution is to avoid swimming or dangling limbs in fresh-water lakes or streams harboring the snails carrying the parasites that cause schistosomiasis (bilharzia).

Contaminated food.

Food may be contaminated at the source by the use of “night soil” (human body wastes) as a fertilizer, in passage by a lack of refrigeration and exposure to flies and other insects, and in preparation by poor hygiene on the part of cooks and food handlers. In this respect, the food prepared by a street vendor where one can see what is being cooked and how it is being prepared may be safer than the “four star” restaurant where the posh ambience and clean uniforms worn by the staff may hide lapses in the storage, preparation and serving of the food. The old adage, “If you can’t boil it or peel it yourself, don’t eat it” is probably the best advice one can give the traveller.

Traveller’s diarrhoea.

Travellers’ diarrhoea is encountered worldwide in modern urban centres as well as in undeveloped areas. While most cases are attributed to organisms in food and drink, many are simply the result of strange foods and food preparation, dietary indiscretions and fatigue. Some cases may also follow bathing or showering in unsafe water or swimming in contaminated lakes, streams and pools.

Most cases are self-limited and respond promptly to such simple measures as maintaining an adequate fluid intake, a light bland diet and rest. Simple medications such as attapulgite (a clay product that acts as an absorbent), bismuth subsalicylate and anti-motility agents such as loperamide or reglan may help to control the diarrhoea. However, when the diarrhoea is unusually severe, lasts more than three days, or is accompanied by repeated vomiting or fever, medical attention and the use of appropriate antibiotics are advisable. Selection of the antibiotic of choice is guided by laboratory identification of the offending organism or, if that is not feasible, by an analysis of the symptoms and epidemiological information about the prevalence of particular infections in the areas visited. The traveller should be provided with a pamphlet such as the one developed by the World Health Organization (figure 2) that explains what to do in simple, non-alarming language.

Prophylactic use of antibiotics has been suggested before one enters an area where water and food are suspect, but this is generally frowned upon since the antibiotics themselves may cause symptoms and taking them in advance may lead the traveller to ignore or become lax towards the precautions that have been advised.

Figure 2. A sample of a World Health Organization educational pamphlet on traveller’s diarrhoea.

MISSING

In some cases, the onset of the diarrhoea may not occur until after the return home. This is particularly suggestive of parasitic disease and is an indication that the appropriate laboratory tests be made to determine whether such an infection exists.

Altitude sickness.

Travellers to mountainous regions such as Aspen, Colorado, Mexico City or La Paz, Bolivia, may have difficulty with the altitude, particularly those with coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure or lung diseases such as emphysema, chronic bronchitis or asthma. When mild, altitude sickness may cause fatigue, headache, exertional dyspnoea, insomnia or nausea. These symptoms generally subside after a few days of diminished physical activity and rest.

When more severe, these symptoms may progress to respiratory distress, vomiting and blurred vision. When this occurs, the traveller should seek medical attention and get to a lower altitude as quickly as possible, perhaps meanwhile even inhaling supplementary oxygen.

Crime and civil unrest.

Most travellers will have the sense to avoid war zones and areas of civil unrest. However, while in strange cities, they may unwittingly stray into neighbourhoods where violent crime is prevalent and where tourists are popular targets. Instructions on safeguarding jewelry and other valuables, and maps showing safe routes from the airport to the centre of the city and which areas to shun, may be helpful in avoiding being victimized.

Fatigue.

Simple fatigue is a frequent cause of discomfort and impaired performance. A good deal of the difficulty attributed to jet lag is often the result of the rigours of travel in planes, buses and automobiles, poor sleep in strange beds and strange surroundings, overeating and alcohol consumption, and schedules of business and social engagements that are too full and demanding.

The business traveller is often bedevilled by the volume of work to clear up prior to departure as well as in preparing for the trip, to say nothing of catching up after the return home. Teaching the traveller to prevent the accumulation of undue fatigue while educating the executive to whom he or she reports to consider this ubiquitous hazard in laying out the assignment is often a key element in the travel protection programme.

Conclusion

With the increase in travel to strange and distant places for business and for pleasure, protecting the health of the traveller has become an important element in the worksite health promotion programme. It involves sensitizing the traveller to the hazards that will be encountered and providing the information and the tools needed to circumvent them. It includes medical services such as the pre-travel consultations, immunizations and provisions of medications that are likely to be needed en route. Participation by the organization’s management is also important in developing reasonable expectations for the mission, and making suitable travel and living arrangements for the trip. The goal is successful completion of the mission and the safe return of a healthy, travelling employee.