In its Health of the Nation policy declaration, the government of the United Kingdom subscribed to the twin strategy (to paraphrase their statement of aims) of (1) “adding years to life” by seeking an increase in life expectancy and a reduction in premature death, and (2) “adding life to years” by increasing the number of years lived free from ill-health, by reducing or minimizing the adverse effects of illness and disability, by promoting healthy lifestyles and by improving physical and social environments—in short, by improving the quality of life.

It was felt that efforts to achieve these aims would be more successful if they were exerted in already existent “settings”, namely schools, homes, hospitals and workplaces.

While it was known that there was considerable health promotion activity at the workplace (European Foundation 1991), no comprehensive baseline information existed on the level and nature of workplace health promotion. Various small-scale surveys had been conducted, but these had all been limited in one way or another, either by being concentrated on a single activity such as smoking, or restricted to a small geographical area or based on a small number of workplaces.

A comprehensive survey of workplace health promotion in England was undertaken on behalf of the Health Education Authority. Two models were used to develop the survey: the 1985 US National Survey of Worksite Health Promotion (Fielding and Piserchia 1989) and a 1984 survey carried out by the Policy Studies Institute of Workplaces in Britain (Daniel 1987).

The survey

There are over 2,000,000 workplaces in England (the workplace is defined as a geographically contiguous setting). The distribution is enormously skewed: 88% of workplaces employ fewer than 25 people onsite and cover about 30% of the workforce; only 0.3% of workplaces employ more than 500 people, yet these few very large sites account for some 20% of total employees.

The survey was originally structured to reflect this distribution by over-sampling the larger worksites in a random sample of all workplaces, including both the public and private sectors and all sizes of workplace; however, those who were self-employed and were working from home were excepted from the survey. The only other exclusions were various public bodies such as defense establishments, police and prison services.

In total 1,344 workplaces were surveyed in March and April of 1992. Interviewing was carried out by telephone, with the average completed interview taking 28 minutes. Interviews were held with whatever person was responsible for health-related activities. At smaller workplaces, this was seldom someone with a health specialization.

Findings of the survey

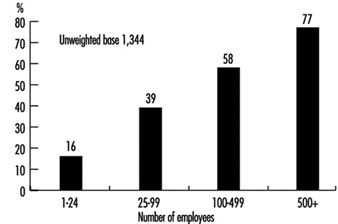

Figure 1 shows the spontaneous response to the inquiry as to whether any health-related activities had been undertaken in the past year and the marked size relationship to type of respondent.

Figure 1. Whether any health-related activities were undertaken in last 12 months.

A succession of spontaneous questions, and questions that were prompted in the course of interviewing, elicited from respondents considerably more information as to the extent and nature of health-related activities. The range of activities and incidence of such activity is shown in table 1. Some of the activities, such as job satisfaction (understood in England as a catch-all term covering such aspects as responsibility for both the pace and content of the work, self-esteem, management-worker relationships and skills and training) are normally regarded as outside the scope of health promotion, but there are commentators who believe that such structural factors are of great importance in improving health.

Table 1. Range of health-related activities by size of workforce.

|

Size of workforce (activity in %) |

|||||

|

All |

1-24 |

25-99 |

100-499 |

500+ |

|

|

Smoking and tobacco |

31 |

29 |

42 |

61 |

81 |

|

Alcohol and sensible drinking |

14 |

13 |

21 |

30 |

46 |

|

Diet |

6 |

5 |

13 |

26 |

47 |

|

Healthy catering |

5 |

4 |

13 |

30 |

45 |

|

Stress management |

9 |

7 |

14 |

111 |

32 |

|

HIV/AIDS and sexual health practices |

9 |

7 |

16 |

26 |

42 |

|

Weight control |

3 |

2 |

4 |

12 |

30 |

|

Exercise and fitness |

6 |

5 |

10 |

20 |

37 |

|

Heart health and heart disease-related activities |

4 |

2 |

9 |

18 |

43 |

|

Breast screening |

3 |

2 |

4 |

15 |

29 |

|

Cervical screening |

3 |

2 |

5 |

12 |

23 |

|

Health screening |

5 |

4 |

10 |

29 |

54 |

|

Lifestyle assessment |

3 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

21 |

|

Cholesterol testing |

4 |

3 |

5 |

11 |

24 |

|

Blood pressure control |

4 |

3 |

9 |

16 |

44 |

|

Drugs and alcohol abuse-related activities |

5 |

4 |

13 |

14 |

28 |

|

Women’s health-related activities |

4 |

4 |

6 |

14 |

30 |

|

Men’s health-related activities |

2 |

2 |

5 |

9 |

32 |

|

Repetitive strain injury avoidance |

4 |

3 |

10 |

23 |

47 |

|

Back care |

9 |

8 |

17 |

25 |

46 |

|

Eyesight |

5 |

4 |

12 |

27 |

56 |

|

Hearing |

4 |

3 |

8 |

18 |

44 |

|

Desk and office layout design |

9 |

8 |

16 |

23 |

45 |

|

Interior ventilation and lighting |

16 |

14 |

26 |

38 |

46 |

|

Job satisfaction |

18 |

14 |

25 |

25 |

32 |

|

Noise |

8 |

6 |

17 |

33 |

48 |

Unweighted base = 1,344.

Other matters that were investigated included the decision-making process, budgets, workforce consultation, awareness of information and advice, benefits of health promotion activity to employer and employee, difficulties in implementation, and perception of the importance of health promotion. There are several general points to make:

- Overall, 40% of all workplaces undertook at least one major health related activity in the previous year. Apart from activity on smoking in workplaces with more than 100 employees, no single health promotion activity occurs in a majority of workplaces ranked by size.

- In small workplaces the only direct health promoting activities of any significance are for smoking and alcohol. Even then, both are of minority incidence (29% and 13%).

- The immediate physical environment, reflected in such factors as ventilation and lighting, are considered to be substantively health related, as is job satisfaction. However, these are mentioned by less than 25% of workplaces with under 100 employees.

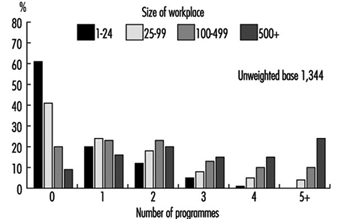

- As the workplace increases in size, it is not just that a higher percentage of workplaces undertake any activity, there is also a wider range of activity in any one workplace. This is shown in figure 15.5, which illustrates the likelihood of one or more of the major programmes. Only 9% of the largest workplaces have no programme at all and over 50% have at least three. In the smallest workplaces, only 19% have two or more programmes. In between, 35% of 25-99 workplaces have two or more programmes, while 56% of 100-499 workplaces have two or more programmes and 33% have three or more. However, it would be too much to read into these figures any semblance of what might be called a “healthy workplace”. Even if such a workplace were defined as one with 5+ programmes in place, there needs to a be an evaluation of the nature and intensity of the programme. In-depth interviewing suggests that in very few instances is the health activity integrated into a planned health promotion function and in even fewer cases, if any, is there modification of either the practices or objectives of the workplace to increase the emphasis on health enhancement.

- After smoking programmes, which get an 81% incidence in the largest workplaces, and alcohol, the next highest incidences are for eyesight testing, health screening and back care.

- Breast and cervical screening have a low incidence, even in workplaces with 60%+ of female employees (see table 2).

- Public sector workplaces show double the level of incidence for activities of those in the private sector. This holds across all the activities

- In regard to smoking and alcohol, foreign-owned companies have a higher incidence of workplace activity than British ones. However, the differential is relatively minor in most activities apart from health screening (15% against 5%) and the concomitant activities such as cholesterol and blood pressure.

- Only in the public sector is there a significant involvement in HIV/AIDS activity. In most of the activities the public sector outperforms the other industry sectors with the notable exception of alcohol.

- Workplaces which have no health promotion activity are virtually all small or medium-size in the private sector, British-owned and predominantly in the distribution and catering industries.

Figure 2. Likelihood of number of major health promotion programmes, by size of workforce.

Table 2. Participation rates in breast and cervical cancer screening (spontaneous and prompted) by percentage of female workforce.

|

Percentage of the workforce that is female |

||

|

More than 60% |

Less than 60% |

|

|

Breast screening |

4% |

2% |

|

Cervical screening |

4% |

2% |

Unweighted base = 1,344.

Discussion

The quantitative telephone survey and the parallel face-to-face interviewing revealed a considerable amount of information as to the level of health promotion activity at the workplace in England.

In a study of this nature, it is not possible to untangle all the confounding variables. However, it would seem that size of workplace, in terms of number of employees, public as opposed to private ownership, levels of unionization, and the nature of the work itself are important factors.

Communication of health promotion messages is largely through group methods such as posters, leaflets or videos. In larger workplaces there is a far greater likelihood of individual counseling being available, particularly for things like smoking cessation, alcohol problems and stress management. It is clear from the research methods used that health promotion activities are not “embedded” in the workplace and are highly contingent activities which, in the large majority of cases, are dependent for effectiveness on individuals. To date, health promotion has not made out the necessary cost/benefit base for its implementation. Such a cost/benefit calculation need not be a detailed and sophisticated analysis but simply an indication that it is of value. Such an indication may be of great benefit in persuading more private sector workplaces to increase their activity levels. There are very few of what might be termed “healthy workplaces”. In very few instances is the health promotion activity integrated into a planned health promotion function and in even fewer cases, if any, is there modification of either the practice or objectives of the workplace to increase emphasis on health enhancement.

Conclusion

Health promotion activities seem to be increasing, with 37% of respondents claiming that such activity had increased in the previous year. Health promotion is considered to be an important issue, with even 41% of small workplaces saying it was very important. Considerable benefits to employee health and fitness were ascribed to health promotion activities, as was reduced absenteeism and sickness.

However, there is little formal evaluation, and while written policies have been introduced, they are by no means universal. While there is support for the aims of health promotion and positive advantages are perceived, there is yet too little evidence of institutionalization of the activities into the culture of the workplace. Workplace health promotion in England seems to be contingent and vulnerable.