Evolution and Structure of the Industry

Papermaking is thought to have originated in China in about 100 A.D. using rags, hemp and grasses as the raw material, and beating against stone mortars as the original fibre separation process. Although mechanization increased over the intervening years, batch production methods and agricultural fibre sources remained in use until the 1800s. Continuous papermaking machines were patented at the turn of that century. Methods for pulping wood, a more abundant fibre source than rags and grasses, were developed between 1844 and 1884, and included mechanical abrasion as well as the soda, sulphite, and sulphate (kraft) chemical methods. These changes initiated the modern pulp and paper manufacturing era.

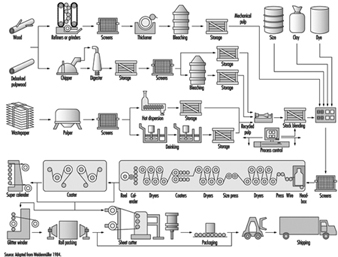

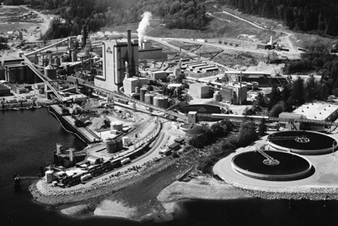

Figure 1 illustrates the major pulp and paper making processes in the current era: mechanical pulping; chemical pulping; repulping waste paper; papermaking; and converting. The industry today can be divided into two main sectors according to the types of products manufactured. Pulp is generally manufactured in large mills in the same regions as the fibre harvest (i.e., mainly forest regions). Most of these mills also manufacture paper - for example, newsprint, writing, printing or tissue papers; or they may manufacture paperboards. (Figure 2 shows such a mill, which produces bleached kraft pulp, thermomechanical pulp and newsprint. Note the rail yard and dock for shipping, chip storage area, chip conveyors leading to digester, recovery boiler (tall white building) and effluent clarifying ponds). Separate converting operations are usually situated close to consumer markets and use market pulp or paper to manufacture bags, paperboards, containers, tissues, wrapping papers, decorative materials, business products and so on.

Figure 1. Illustration of process flow in pulp and paper manufacturing operations

Figure 2. Modern pulp and paper mill complex situated on a coastal waterway

Canfor Library

There has been a trend in recent years for pulp and paper operations to become part of large, integrated forest product companies. These companies have control of forest harvesting operations (see the Forestry chapter), lumber milling (see the Lumber industry chapter), pulp and paper manufacturing, as well as converting operations. This structure ensures that the company has an ongoing source of fibre, efficient use of wood waste and assured buyers, which often leads to increased market share. Integration has been operating in tandem with increasing concentration of the industry into fewer companies and increasing globalization as companies pursue international investments. The financial burden of plant development in this industry has encouraged these trends to allow economies of scale. Some companies have now reached production levels of 10 million tonnes, similar to the output of countries with the highest production. Many companies are multinational, some with plants in 20 or more countries worldwide. However, even though many of the smaller mills and companies are disappearing, the industry still has hundreds of participants. As an illustration, the top 150 companies account for two-thirds of pulp and paper output and only one-third of the industry’s employees.

Economic Importance

The manufacture of pulp, paper and paper products ranks among the world’s largest industries. Mills are found in more than 100 countries in every region of the world, and directly employ more than 3.5 million people. The major pulp and paper producing nations include the United States, Canada, Japan, China, Finland, Sweden, Germany, Brazil and France (each produced more than 10 million tonnes in 1994; see table 1).

Table 1. Employment and production in pulp, paper, and paperboard operations in 1994, selected countries.

|

|

Number |

|

|

||

|

Number |

Production (1,000 |

Number |

Production (1,000 tonnes) |

||

|

Austria |

10,000 |

11 |

1,595 |

28 |

3,603 |

|

Bangladesh |

15,000 |

7 |

84 |

17 |

160 |

|

Brazil |

70,000 |

35 |

6,106 |

182 |

5,698 |

|

Canada |

64,000 |

39 |

24,547 |

117 |

18,316 |

|

China |

1,500,000 |

8,000 |

17,054 |

10,000 |

21,354 |

|

Czech Republic |

18,000 |

9 |

516 |

32 |

662 |

|

Finland |

37,000 |

43 |

9,962 |

44 |

10,910 |

|

Former USSR** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

France |

48,000 |

20 |

2,787 |

146 |

8,678 |

|

Germany |

48,000 |

19 |

1,934 |

222 |

14,458 |

|

India |

300,000 |

245 |

1,400 |

380 |

2,300 |

|

Italy |

26,000 |

19 |

535 |

295 |

6,689 |

|

Japan |

55,000 |

49 |

10,579 |

442 |

28,527 |

|

Korea, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mexico |

26,000 |

10 |

276 |

59 |

2,860 |

|

Pakistan |

65,000 |

2 |

138 |

68 |

235 |

|

Poland** |

46,000 |

5 |

893 |

27 |

1,343 |

|

Romania |

25,000 |

17 |

202 |

15 |

288 |

|

Slovakia |

14,000 |

3 |

304 |

6 |

422 |

|

South Africa |

19,000 |

9 |

2,165 |

20 |

1,684 |

|

Spain |

20,180 |

21 |

626 |

141 |

5,528 |

|

Sweden |

32,000 |

49 |

10,867 |

50 |

9,354 |

|

Taiwan |

18,000 |

2 |

326 |

156 |

4,199 |

|

Thailand |

12,000 |

3 |

240 |

45 |

1,664 |

|

Turkey |

12,000 |

11 |

416 |

34 |

1,102 |

|

United |

|

|

|

|

|

|

United States |

230,000 |

190 |

58,724 |

534 |

80,656 |

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

* Countries included if more than 10,000 people were employed in the industry.

** Data for 1989/90 (ILO 1992).

Source: Data for table adapted from PPI 1995.

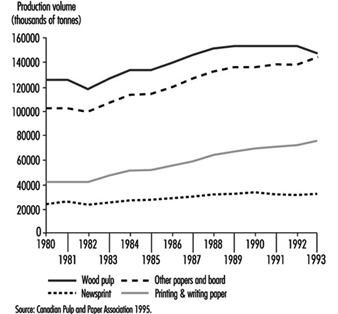

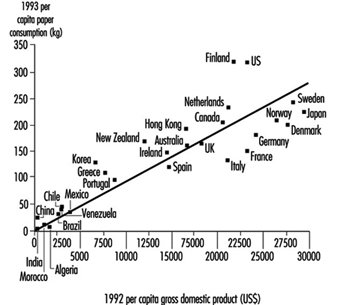

Every country is a consumer. Worldwide production of pulp, paper and paperboard was about 400 million tonnes in 1993. Despite predictions of decreased paper use in the face of the electronic age, there has been a fairly steady 2.5% annual rate of growth in production since 1980 (figure 3). In addition to its economic benefits, the consumption of paper has cultural value resulting from its function in the recording and dissemination of information. Because of this, pulp and paper consumption rates have been used as an indicator of a nation’s socioeconomic development (figure 4).

Figure 3. Pulp and paper production worldwide, 1980 to 1993

Figure 4. Paper and paperboard consumption as an indicator of economic development

The main source of fibre for pulp production over the last century has been wood from temperate coniferous forests, though more recently the use of tropical and boreal woods has been increasing (see the chapter Lumber for data on industrial roundwood harvesting worldwide). Because forested regions of the world are generally sparsely populated, there tends to be a dichotomy between the producing and using areas of the world. Pressure from environmental groups to preserve forest resources by using recycled paper stocks, agricultural crops and short-rotation plantation forests as fibre sources may change the distribution of pulp and paper production facilities throughout the world over the coming decades. Other forces, including increased paper consumption in the developing world and globalization, are also expected to play a role in relocating the industry.

Characteristics of the Workforce

Table 1 indicates the size of the workforce directly employed in pulp and paper production and converting operations in 27 countries, which together represent about 85% of world pulp and paper employment and over 90% of mills and production. In countries which consume most of what they produce (e.g., United States, Germany, France), converting operations provide two jobs for every one in pulp and paper production.

The labour force in the pulp and paper industry mainly holds full-time jobs within traditional management structures, though some mills in Finland, the United States and elsewhere have had success with flexible working hours and self-managed job-rotation teams. Because of their high capital costs, most pulping operations run continuously and require shift work; this is not true of converting plants. Working hours vary with the patterns of employment prevalent in each country, with a range from about 1,500 to more than 2,000 hours per year. In 1991, incomes in the industry ranged from US$1,300 (unskilled workers in Kenya) to US$70,000 per year (skilled production personnel in the United States) (ILO 1992). Male workers predominate in this industry, with women usually representing only 10 to 20% of the labour force. China and India may form the upper and lower ends of the range with 35% and 5% women respectively.

Management and engineering personnel at pulp and paper mills usually have university-level training. In European countries, most of the skilled blue-collar workforce (e.g., papermakers) and many of the unskilled workforce have had several years of trade-school education. In Japan, formal in-house training and upgrading is the norm; this approach is being adopted by some Latin American and North American companies. However, in many operations in North America and in the developing world, informal on-the-job training is more common for blue-collar jobs. Surveys have shown that, in some operations, many workers have literacy problems and are poorly prepared for the life-long learning required in the dynamic and potentially hazardous environment of this industry.

The capital costs of building modern pulp and paper plants are extremely high (e.g., a bleached kraft mill employing 750 people might cost US$1.5 billion to build; a chemi-thermomechanical pulp (CTMP) mill employing 100 people might cost US$400 million), so there are great economies of scale with high-capacity facilities. New and refitted plants usually use mechanized and continuous processes, as well as electronic monitors and computer controls. They require relatively few employees per unit production (e.g., 1 to 1.2 working hours per tonne of pulp in new Indonesian, Finnish and Chilean mills). Over the last 10 to 20 years, output per employee has increased as a result of incremental advances in technology. The newer equipment allows easier change-overs between product runs, lower inventories and customer-driven just-in-time production. Productivity gains have resulted in job losses in many producing nations in the developed world. However, there have been increases in employment in developing countries, where new mills being constructed, even if sparsely staffed, represent new forays into the industry.

From the 1970s to 1990, there was a decline of about 10% in the proportion of blue-collar jobs in European and North American operations, so that they now represent between 70 and 80% of the workforce (ILO 1992). The use of contract labour for mill construction, maintenance and wood-harvesting operations has been increasing; many operations have reported that 10 to 15% of their on-site workforce are contractors.