Metal Processing and Metal Working

Foundries

Founding, or metal casting, involves the pouring of molten metal into the hollow inside of a heat-resistant mould which is the outside or negative shape of the pattern of the desired metal object. The mould may contain a core to determine the dimensions of any internal cavity in the final casting. Foundry work comprises:

- making a pattern of the desired article

- making the mould and cores and assembling the mould

- melting and refining the metal

- pouring the metal into the mould

- cooling the metal casting

- removing the mould and core from the metal casting

- removing extra metal from the finished casting.

The basic principles of foundry technology have changed little in thousands of years. However, processes have become more mechanized and automatic. Wooden patterns have been replaced by metal and plastic, new substances have been developed for producing cores and moulds, and a wide range of alloys are used. The most prominent foundry process is sand moulding of iron.

Iron, steel, brass and bronze are traditional cast metals. The largest sector of the foundry industry produces grey and ductile iron castings. Gray iron foundries use iron or pig iron (new ingots) to make standard iron castings. Ductile iron foundries add magnesium, cerium or other additives (often called ladle additives) to the ladles of molten metal before pouring to make nodular or malleable iron castings. The different additives have little impact on workplace exposures. Steel and malleable iron make up the balance of the ferrous foundry industrial sector. The major customers of the largest ferrous foundries are the auto, construction and agricultural implement industries. Iron foundry employment has decreased as engine blocks become smaller and can be poured in a single mould, and as aluminium is substituted for cast iron. Non-ferrous foundries, especially aluminium foundry and die-cast operations, have heavy employment. Brass foundries, both free standing and those producing for the plumbing equipment industry, are a shrinking sector which, however, remains important from an occupational health perspective. In recent years, titanium, chromium, nickel and magnesium, and even more toxic metals such as beryllium, cadmium and thorium, are used in foundry products.

Although the metal founding industry may be assumed to start by remelting solid material in the form of metal ingots or pigs, the iron and steel industry in the large units may be so integrated that the division is less obvious. For instance, the merchant blast furnace may turn all its output into pig iron, but in an integrated plant some iron may be used to produce castings, thus taking part in the foundry process, and the blast furnace iron may be taken molten to be turned into steel, where the same thing can occur. There is in fact a separate section of the steel trade known for this reason as ingot moulding. In the normal iron foundry, the remelting of pig iron is also a refining process. In the non-ferrous foundries the process of melting may require the addition of metals and other substances, and thus constitutes an alloying process.

Moulds made from silica sand bound with clay predominate in the iron foundry sector. Cores traditionally produced by baking silica sand bound with vegetable oils or natural sugars have been substantially replaced. Modern founding technology has developed new techniques to produce moulds and cores.

In general, the health and safety hazards of foundries can be classified by type of metal cast, moulding process, size of casting and degree of mechanization.

Process Overview

On the basis of the designer’s drawings, a pattern conforming to the external shape of the finished metal casting is constructed. In the same way, a corebox is made that will produce suitable cores to dictate the internal configuration of the final article. Sand casting is the most widely used method, but other techniques are available. These include: permanent mould casting, using moulds of iron or steel; die casting, in which the molten metal, often a light alloy, is forced into a metal mould under pressures of 70 to 7,000 kgf/cm2; and investment casting, where a wax pattern is made of each casting to be produced and is covered with refractory which will form the mould into which the metal is poured. The “lost foam” process uses polystyrene foam patterns in sand to make aluminium castings.

Metals or alloys are melted and prepared in a furnace which may be of the cupola, rotary, reverberatory, crucible, electric arc, channel or coreless induction type (see table 1). Relevant metallurgical or chemical analyses are performed. Molten metal is poured into the assembled mould either via a ladle or directly from the furnace. When the metal has cooled, the mould and core material are removed (shakeout, stripping or knockout) and the casting is cleaned and dressed (despruing, shot-blasting or hydro-blasting and other abrasive techniques). Certain castings may require welding, heat treatment or painting before the finished article will meet the specifications of the buyer.

Table 1. Types of foundry furnaces

|

Furnace |

Description |

|

Cupola furnace |

A cupola furnace is a tall, vertical furnace, open at the top with hinged doors at the bottom. It is charged from the top with alternate layers of coke, limestone and metal; the molten metal is removed at the bottom. Special hazards include carbon monoxide and heat. |

|

Electric arc furnace |

The furnace is charged with ingots, scrap, alloy metals and fluxing agents. An arc is produced between three electrodes and the metal charge, melting the metal. A slag with fluxes covers the surface of the molten metal to prevent oxidation, to refine the metal and protect the furnace roof from excessive heat. When ready, the electrodes are raised and the furnace tilted to pour the molten metal into the receiving ladle. Special hazards include metal fumes and noise. |

|

Induction furnace |

An induction furnace melts the metal by passing a high electric current through copper coils on the outside of the furnace, inducing an electric current in the outer edge of the metal charge that heats the metal because of the high electrical resistance of the metal charge. Melting progresses from the outside of the charge to the inside. Special hazards include metal fumes. |

|

Crucible furnace |

The crucible or container holding the metal charge is heated by a gas or oil burner. When ready, the crucible is lifted out of the furnace and tilted for pouring into moulds. Special hazards include carbon monoxide, metal fumes, noise and heat. |

|

Rotary furnace |

A long, inclined rotating cylindrical furnace that is charged from the top and fired from the lower end. |

|

Channel furnace |

A type of induction furnace. |

|

Reverberatory furnace |

This horizontal furnace consists of a fireplace at one end, separated from the metal charge by a low partition wall called the fire-bridge, and a stack or chimney at the other end. The metal is kept from contact with the solid fuel. Both the fireplace and metal charge are covered by an arched roof. The flame in its path from the fireplace to the stack is reflected downwards or reverberated on the metal beneath, melting it. |

Hazards such as the danger arising from the presence of hot metal are common to most foundries, irrespective of the particular casting process employed. Hazards may also be specific to a particular foundry process. For example, the use of magnesium presents flare risks not encountered in other metal founding industries. This article emphasizes iron foundries, which contain most of the typical foundry hazards.

The mechanized or production foundry employs the same basic methods as the conventional iron foundry. When moulding is done, for example, by machine and castings are cleaned by shot blasting or hydroblasting, the machine usually has built-in dust control devices, and the dust hazard is reduced. However, sand is frequently moved from place to place on an open-belt conveyor, and transfer points and sand spillage may be sources of considerable quantities of airborne dust; in view of the high production rates, the airborne dust burden may be even higher than in the conventional foundry. A review of air sampling data in the middle 1970s showed higher dust levels in large American production foundries than in small foundries sampled during the same period. Installation of exhaust hoods over transfer points on belt conveyors, combined with scrupulous housekeeping, should be normal practice. Conveying by pneumatic systems is sometimes economically possible and results in a virtually dust-free conveying system.

Iron Foundries

For simplicity, an iron foundry can be presumed to comprise the following six sections:

- metal melting and pouring

- pattern-making

- moulding

- coremaking

- shakeout/knockout

- casting cleaning.

In many foundries, almost any of these processes may be carried out simultaneously or consecutively in the same workshop area.

In a typical production foundry, iron moves from melting to pouring, cooling, shakeout, cleaning and shipping as a finished casting. Sand is cycled from sand mix, moulding, shakeout and back to sand mixing. Sand is added to the system from core making, which starts with new sand.

Melting and pouring

The iron founding industry relies heavily on the cupola furnace for metal melting and refining. The cupola is a tall, vertical furnace, open at the top with hinged doors at the bottom, lined with refractory and charged with coke, scrap iron and limestone. Air is blown through the charge from openings (tuyers) at the bottom; combustion of coke heats, melts and purifies the iron. Charge materials are fed into the top of the cupola by crane during operation and must be stored close at hand, usually in compounds or bins in the yard adjacent to the charging machinery. Tidiness and efficient supervision of the stacks of raw materials are essential to minimize the risk of injury from slippages of heavy objects. Cranes with large electromagnets or heavy weights are often used to reduce the scrap metal to manageable sizes for charging into the cupola and for filling the charging hoppers themselves. The crane cab should be well protected and the operators properly trained.

Employees handling raw materials should wear hand leathers and protective boots. Careless charging can overfill the hopper and can cause dangerous spillage. If the charging process is found to be too noisy, the noise of metal-on-metal impact can be reduced by fitting rubber noise-dampening liners to storage skips and bins. The charging platform is necessarily above ground level and can present a hazard unless it is level and has a non-slip surface and strong rails around it and any floor openings.

Cupolas generate large quantities of carbon monoxide, which may leak from the charging doors and be blown back by local eddy currents. Carbon monoxide is invisible, odourless and can quickly produce toxic ambient levels. Employees working on the charging platform or surrounding catwalks should be well trained in order to recognize the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning. Both continuous and spot monitoring of exposure levels are needed. Self-contained breathing apparatus and resuscitation equipment should be maintained in readiness, and operators should be instructed in their use. When emergency work is carried out, a confined-space entry system of contaminant monitoring should be developed and enforced. All work should be supervised.

Cupolas are usually sited in pairs or groups, so that while one is being repaired the others operate. The period of use must be based on experience with durability of refractories and on engineering recommendations. Procedures must be worked out in advance for tapping out iron and for shutting down when hot spots develop or if the water cooling system is disabled. Cupola repair necessarily involves the presence of employees inside the cupola shell itself to mend or renew refractory linings. These assignments should be considered confined-space entries and appropriate precautions taken. Precautions should also be taken to prevent the discharge of material through the charging doors at such times. To protect the workers from falling objects, they should wear safety helmets and, if working at a height, safety harnesses.

Workers tapping cupolas (transferring molten metal from the cupola well to a holding furnace or ladle) must observe rigorous personal protection measures. Goggles and protective clothing are essential. The eye protectors should resist both high velocity impact and molten metal. Extreme caution should be exercised in order to prevent remaining molten slag (the unwanted debris removed from the melt with the aid of the limestone additives) and metal from coming into contact with water, which will cause a steam explosion. Tappers and supervisors must ensure that any person not involved in the operation of the cupola remains outside the danger area, which is delineated by a radius of about 4 m from the cupola spout. Delineation of a non-authorized no-entry zone is a statutory requirement under the British Iron and Steel Foundries Regulations of 1953.

When the cupola run is at an end, the cupola bottom is dropped to remove the unwanted slag and other material still inside the shell before employees can carry out the routine refractory maintenance. Dropping the cupola bottom is a skilled and dangerous operation requiring trained supervision. A refractory floor or layer of dry sand on which to drop the debris is essential. If a problem occurs, such as jammed cupola bottom doors, great caution must be exercised to avoid risks of burns to workers from the hot metal and slag.

Visible white-hot metal is a danger to workers’ eyes due to the emission of infrared and ultraviolet radiation, extensive exposure to which can cause cataracts.

The ladle must be dried before filling with molten metal, to prevent steam explosions; a satisfactory period of flame heating must be established.

Employees in metal and pouring sections of the foundry should be provided with hard hats, tinted eye protection and face shields, aluminized clothing such as aprons, gaiters or spats (lower-leg and foot coverings) and boots. Use of protective equipment should be mandatory, and there should be adequate instruction in its use and maintenance. High standards of housekeeping and exclusion of water to the highest degree possible are needed in all areas where molten metal is being manipulated.

Where large ladles are slung from cranes or overhead conveyors, positive ladle-control devices should be employed to ensure that spillage of metal cannot occur if the operator releases his or her hold. Hooks holding molten metal ladles must be periodically tested for metal fatigue to prevent failure.

In production foundries, the assembled mould moves along a mechanical conveyor to a ventilated pouring station. Pouring may be from a manually controlled ladle with mechanical assist, an indexing ladle controlled from a cab, or it can be automatic. Typically, the pouring station is provided with a compensating hood with a direct air supply. The poured mould proceeds along the conveyor through an exhausted cooling tunnel until shakeout. In smaller, job shop foundries, moulds may be poured on a foundry floor and allowed to burn off there. In this situation, the ladle should be equipped with a mobile exhaust hood.

Tapping and transport of molten iron and charging of electric furnaces creates exposure to iron oxide and other metal oxide fumes. Pouring into the mould ignites and pyrolyses organic materials, generating large amounts of carbon monoxide, smoke, carcinogenic polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and pyrolysis products from core materials which may be carcinogenic and also respiratory sensitizers. Moulds containing large polyurethane bound cold box cores release a dense, irritating smoke containing isocyanates and amines. The primary hazard control for mould burn off is a locally exhausted pouring station and cooling tunnel.

In foundries with roof fans for exhausting pouring operations, high metal fume concentrations may be found in the upper regions where crane cabs are located. If the cabs have an operator, the cabs should be enclosed and provided with filtered, conditioned air.

Pattern making

Pattern making is a highly skilled trade translating the two-dimensional design plans to a three-dimensional object. Traditional wooden patterns are made in standard workshops containing hand tools and electric cutting and planing equipment. Here, all reasonably practicable measures should be taken to reduce the noise to the greatest extent possible, and suitable ear protectors must be provided. It is important that the employees are aware of the advantages of using such protection.

Power-driven wood cutting and finishing machines are obvious sources of danger, and often suitable guards cannot be fitted without preventing the machine from functioning at all. Employees must be well versed in normal operating procedure and should also be instructed in the hazards inherent in the work.

Wood sawing can create dust exposure. Efficient ventilation systems should be fitted to eliminate wood dust from the pattern shop atmosphere. In certain industries using hard woods, nasal cancer has been observed. This has not been studied in the founding industry.

Casting in permanent metal moulds, as in die-casting, has been an important development in the foundry industry. In this case, pattern making is largely replaced by engineering methods and is really a die manufacture operation. Most of the pattern-making hazards and the risks from sand are eliminated, but are replaced by the risk inherent in the use of some sort of refractory material to coat the die or mould. In modern die-foundry work, increasing use is made of sand cores, in which case the dust hazards of the sand foundry are still present.

Moulding

The most common moulding process in the iron founding industry uses the traditional “green sand” mould made from silica sand, coal dust, clay and organic binders. Other methods of mould production are adapted from coremaking: thermosetting, cold self-setting and gas-hardened. These methods and their hazards will be discussed under coremaking. Permanent moulds or the lost foam process may also be used, especially in the aluminium foundry industry.

In production foundries, sand mix, moulding, mould assembly, pouring and shakeout are integrated and mechanized. Sand from shakeout is recycled back to the sand mix operation, where water and other additives are added and the sand is mixed in mullers to maintain the desired physical properties.

For ease of assembly, patterns (and their moulds) are made in two parts. In manual mould-making, the moulds are enclosed in metal or wooden frames called flasks. The bottom half of the pattern is placed in the bottom flask (the drag), and first fine sand and then heavy sand are poured around the pattern. The sand is compacted in the mould by a jolt-squeeze, sand slinger or pressure process. The top flask (the cope) is prepared similarly. Wooden spacers are placed in the cope to form the sprue and riser channels, which are the pathway for the molten metal to flow into the mould cavity. The patterns are removed, the core inserted, and then the two halves of the mould assembled and fastened together, ready for pouring. In production foundries, the cope and drag flasks are prepared on a mechanical conveyor, cores are placed in the drag flask, and the mould assembled by mechanical means.

Silica dust is a potential problem wherever sand is handled. Moulding sand is usually either damp or mixed with liquid resin, and is therefore less likely to be a significant source of respirable dust. A parting agent such as talc is sometimes added to promote the ready removal of the pattern from the mould. Respirable talc causes talcosis, a type of pneumoconiosis. Parting agents are more widespread where hand moulding is employed; in the larger, more automatic processes they are rarely seen. Chemicals are sometimes sprayed onto the mould surface, suspended or dissolved in isopropyl alcohol, which is then burned off to leave the compound, usually a type of graphite, coating the mould in order to achieve a casting with a finer surface finish. This involves an immediate fire risk, and all employees involved in applying these coatings should be provided with fire-retardant protective clothing and hand protection, as organic solvents can also cause dermatitis. Coatings should be applied in a ventilated booth to prevent the organic vapours from escaping into the workplace. Strict precautions should also be observed to ensure that the isopropyl alcohol is stored and used with safety. It should be transferred to a small vessel for immediate use, and the larger storage vessels should be kept well away from the burning-off process.

Manual mould making can involve the manipulation of large and cumbersome objects. The moulds themselves are heavy, as are the moulding boxes or flasks. They are often lifted, moved and stacked by hand. Back injuries are common, and power assists are needed so employees do not need to lift objects too heavy to be carried safely.

Standardized designs are available for enclosures of mixers, conveyors and pouring and shakeout stations with appropriate exhaust volumes and capture and transport velocities. Adherence to such designs and strict preventive maintenance of control systems will attain compliance with international recognized limits for dust exposure.

Coremaking

Cores inserted into the mould determine the internal configuration of a hollow casting, such as the water jacket of an engine block. The core must withstand the casting process but at the same time must not be so strong as to resist removal from the casting during the knocking-out stage.

Prior to the 1960s, core mixtures comprised sand and binders, such as linseed oil, molasses or dextrin (oil sand). The sand was packed in a core box with a cavity in the shape of the core, and then dried in an oven. Core ovens evolve harmful pyrolysis products and require a suitable, well maintained chimney system. Normally, convection currents within the oven will be sufficient to ensure satisfactory removal of fumes from the workplace, although they contribute enormously to air pollution After removal from the oven, the finished oil sand cores can still give rise to a small amount of smoke, but the hazard is minor; in some cases, however, small amounts of acrolein in the fumes may be a considerable nuisance. Cores may be treated with a “flare-off coating” to improve the surface finish of the casting, which calls for the same precautions as in the case of moulds.

Hot box or shell moulding and coremaking are thermosetting processes used in iron foundries. New sand may be mixed with resin at the foundry, or resin-coated sand may be shipped in bags for addition to the coremaking machine. Resin sand is injected into a metal pattern (the core box). The pattern is then heated—by direct natural gas fires in the hot box process or by other means for shell cores and moulding. Hot boxes typically use a furfuryl alcohol (furan), urea- or phenol-formaldehyde thermosetting resin. Shell moulding uses a urea- or phenol-formaldehyde resin. After a short curing time, the core hardens considerably and can be pushed clear of the pattern plate by ejector pins. Hot box and shell coremaking generate substantial exposure to formaldehyde, which is a probable carcinogen, and other contaminants, depending on the system. Control measures for formaldehyde include direct air supply at the operator station, local exhaust at the corebox, enclosure and local exhaust at the core storage station and low-formaldehyde-emission resins. Satisfactory control is difficult to achieve. Medical surveillance for respiratory conditions should be provided to coremaking workers. Phenol- or urea-formaldehyde resin contact with the skin or eyes must be prevented because the resins are irritants or sensitizers and can cause dermatitis. Copious washing with water will help to avoid the problem.

Cold-setting (no-bake) hardening systems presently in use include: acid-catalyzed urea- and phenol-formaldehyde resins with and without furfuryl alcohol; alkyd and phenolic isocyanates; Fascold; self-set silicates; Inoset; cement sand and fluid or castable sand. Cold-setting hardeners do not require external heating to set. The isocyanates employed in binders are normally based on methylene diphenyl isocyanate (MDI), which, if inhaled, can act as a respiratory irritant or sensitizer, causing asthma. Gloves and protective goggles are advisable when handling or using these compounds. The isocyanates themselves should be carefully stored in sealed containers in dry conditions at a temperature between 10 and 30°C. Empty storage vessels should be filled and soaked for 24 hours with a 5% sodium carbonate solution in order to neutralize any residual chemical left in the drum. Most general housekeeping principles should be strictly applied to resin moulding processes, but the greatest caution of all should be exercised when handling the catalysts used as setting agents. The catalysts for the phenol and oil isocyanate resins are usually aromatic amines based on pyridine compounds, which are liquids with a pungent smell. They can cause severe skin irritation and renal and hepatic damage and can also affect the central nervous system. These compounds are supplied either as separate additives (three-part binder) or are ready mixed with the oil materials, and LEV should be provided at the mixing, moulding, casting and knockout stages. For certain other no-bake processes the catalysts used are phosphoric or various sulphonic acids, which are also toxic; accidents during transport or use should be adequately guarded against.

Gas-hardened coremaking comprises the carbon dioxide (CO2)-silicate and the Isocure (or “Ashland”) processes. Many variations of the CO2-silicate process have been developed since the 1950s. This process has generally been used for the production of medium to large moulds and cores. The core sand is a mixture of sodium silicate and silica sand, usually modified by adding such substances as molasses as breakdown agents. After the core box is filled, the core is cured by passing carbon dioxide through the core mixture. This forms sodium carbonate and silica gel, which acts as a binder.

Sodium silicate is an alkaline substance, and can be harmful if it comes into contact with the skin or eyes or is ingested. It is advisable to provide an emergency shower close to areas where large quantities of sodium silicate are handled and gloves should always be worn. A readily available eye-wash fountain should be located in any foundry area where sodium silicate is used. The CO2 can be supplied as a solid, liquid or gas. Where it is supplied in cylinders or pressure tanks, a great many housekeeping precautions should be taken, such as cylinder storage, valve maintenance, handling and so on. There is also the risk from the gas itself, since it can lower the oxygen concentration in the air in enclosed spaces.

The Isocure process is used for cores and moulds. This is a gas-setting system in which a resin, frequently phenol-formaldehyde, is mixed with a di-isocyanate (e.g., MDI) and sand. This is injected into the core box and then gassed with an amine, usually either triethylamine or dimethylethylamine, to cause the crosslinking, setting reaction. The amines, often sold in drums, are highly volatile liquids with a strong smell of ammonia. There is a very real risk of fire or explosion, and extreme care should be taken, especially where the material is stored in bulk. The characteristic effect of these amines is to cause halo vision and corneal swelling, although they also affect the central nervous system, where they can cause convulsions, paralysis and, occasionally, death. Should some of the amine come into contact with the eyes or skin, first-aid measures should include washing with copious quantities of water for at least 15 minutes and immediate medical attention. In the Isocure process, the amine is applied as a vapour in a nitrogen carrier, with excess amine scrubbed through an acid tower. Leakage from the corebox is the principle cause of high exposure, although offgassing of amine from manufactured cores is also significant. Great care should be taken at all times when handling this material, and suitable exhaust ventilation equipment should be installed to remove vapours from the working areas.

Shakeout, casting extraction and core knockout

After the molten metal has cooled, the rough casting must be removed from the mould. This is a noisy process, typically exposing operators well above 90 dBA over an 8 hour working day. Hearing protectors should be provided if it is not practicable to reduce the noise output. The main bulk of the mould is separated from the casting usually by jarring impact. Frequently the moulding box, mould and casting are dropped onto a vibrating grid to dislodge the sand (shakeout). The sand then drops through the grid into a hopper or onto a conveyor where it can be subjected to magnetic separators and recycled for milling, treatment and re-use, or merely dumped. Sometimes hydroblasting can be used instead of a grid, creating less dust. The core is removed here, also sometimes using high-pressure water streams.

The casting is then removed and transferred to the next stage of the knockout operation. Often small castings can be removed from the flask by a “punch-out” process before shakeout, which produces less dust. The sand gives rise to hazardous silica dust levels because it has been in contact with molten metal and is therefore very dry. The metal and sand remain very hot. Eye protection is needed. Walking and working surfaces must be kept free of scrap, which is a tripping hazard, and of dust, which can be resuspended to pose an inhalation hazard.

Relatively few studies have been carried out to determine what effect, if any, the new core binders have on the health of the de-coring operator in particular. The furanes, furfuryl alcohol and phosphoric acid, urea- and phenol-formaldehyde resins, sodium silicate and carbon dioxide, no-bakes, modified linseed oil and MDI, all undergo some type of thermal decomposition when exposed to the temperatures of the molten metals.

No studies have yet been conducted on the effect of the resin-coated silica particle on the development of pneumoconiosis. It is not known whether these coatings will have an inhibiting or accelerating effect on lung-tissue lesions. It is feared that the reaction products of phosphoric acid may liberate phosphine. Animal experiments and some selected studies have shown that the effect of the silica dust on lung tissue is greatly accelerated when silica has been treated with a mineral acid. Urea- and phenol-formaldehyde resins can release free phenols, aldehydes and carbon monoxide. The sugars added to increase collapsibility produce significant amounts of carbon monoxide. No-bakes will release isocyanates (e.g., MDI) and carbon monoxide.

Fettling (cleaning)

Casting cleaning, or fettling, is carried out following shakeout and core knockout. The various processes involved are variously designated in different places but can be broadly classified as follows:

- Dressing covers stripping, roughing or mucking-off, removal of adherent moulding sand, core sand, runners, risers, flash and other readily disposable matter with hand tools or portable pneumatic tools.

- Fettling covers removal of burnt-on moulding sand, rough edges, surplus metal, such as blisters, stumps of gates, scabs or other unwanted blemishes, and the hand cleaning of the casting using hand chisels, pneumatic tools and wire brushes. Welding techniques, such as oxyacetylene-flame cutting, electric arc, arc-air, powder washing and the plasma torch, may be employed for burning off headers, for casting repair and for cutting and washing.

Sprue removal is the first dressing operation. As much as half of the metal cast in the mould is not part of the final casting. The mould must include reservoirs, cavities, feeders and sprue in order that it be filled with metal to complete the cast object. The sprue usually can be removed during the knockout stage, but sometimes this must be carried out as a separate stage of the fettling or dressing operation. Sprue removal is done by hand, usually by knocking the casting with a hammer. To reduce noise, the metal hammers can be replaced by rubber-covered ones and the conveyors lined with the same noise-damping rubber. Hot metal fragments are thrown off and pose an eye hazard. Eye protection must be used. Detached sprues should normally be returned to the charging region of the melting plant and should not be permitted to accumulate at the despruing section of the foundry. After despruing (but sometimes before) most castings are shot blasted or tumbled to remove mould materials and perhaps to improve the surface finish. Tumbling barrels generate high noise levels. Enclosures may be necessary, which can also require LEV.

Dressing methods in steel, iron and non-ferrous foundries are very similar, but special difficulties exist in the dressing and fettling of steel castings owing to greater amounts of burnt-on fused sand compared to iron and non-ferrous castings. Fused sand on large steel castings may contain cristobalite, which is more toxic than the quartz found in virgin sand.

Airless shot blasting or tumbling of castings before chipping and grinding is needed to prevent overexposure to silica dust. The casting must be free of visible dust, although a silica hazard may still be generated by grinding if silica is burnt into the apparently clean metal surface of the casting. The shot is centrifugally propelled at the casting, and no operator is required inside the unit. The blast cabinet must be exhausted so no visible dust escapes. Only when there is a breakdown or deterioration of the shot-blast cabinet and/or the fan and collector is there a dust problem.

Water or water and sand or pressure shot blasting may be used to remove adherent sand by subjecting the casting to a high-pressure stream of either water or iron or steel shot. Sand blasting has been banned in several countries (e.g., the United Kingdom) because of the silicosis risk as the sand particles become finer and finer and the respirable fraction thus continually increases. The water or shot is discharged through a gun and can clearly present a risk to personnel if not handled correctly. Blasting should always be carried out in an isolated, enclosed space. All blasting enclosures should be inspected at regular intervals to ensure that the dust extraction system is functioning and that there are no leaks through which shot or water could escape into the foundry. Blasters’ helmets should be approved and carefully maintained. It is advisable to post a notice on the door to the booth, warning employees that blasting is under way and that unauthorized entry is prohibited. In certain circumstances delay bolts linked to the blast drive motor can be fitted to the doors, making it impossible to open the doors until blasting has ceased.

A variety of grinding tools are used to smooth the rough casting. Abrasive wheels may be mounted on floor-standing or pedestal machines or in portable or swing-frame grinders. Pedestal grinders are used for smaller castings that can be easily handled; portable grinders, surface disc wheels, cup wheels and cone wheels are used for a number of purposes, including smoothing of internal surfaces of castings; swing-frame grinders are used primarily on large castings that require a great deal of metal removal.

Other Foundries

Steel founding

Production in the steel foundry (as distinct from a basic steel mill) is similar to that in the iron foundry; however, the metal temperatures are much higher. This means that eye protection with coloured lenses is essential and that the silica in the mould is converted by heat to tridymite or crystobalite, two forms of crystalline silica which are particularly dangerous to the lungs. Sand often becomes burnt on to the casting and has to be removed by mechanical means, which give rise to dangerous dust; consequently, effective dust exhaust systems and respiratory protection are essential.

Light-alloy founding

The light-alloy foundry uses mainly aluminium and magnesium alloys. These often contain small amounts of metals which may give off toxic fumes under certain circumstances. The fumes should be analysed to determine their constituents where the alloy might contain such components.

In aluminium and magnesium foundries, melting is commonly done in crucible furnaces. Exhaust vents around the top of the pot for removing fumes are advisable. In oil-fired furnaces, incomplete combustion due to faulty burners may result in products such as carbon monoxide being released into the air. Furnace fumes may contain complex hydrocarbons, some of which may be carcinogenic. During furnace and flue cleaning there is the hazard of exposure to vanadium pentoxide concentrated in furnace soot from oil deposits.

Fluorspar is commonly used as a flux in aluminium melting, and significant quantities of fluoride dust may be released to the environment. In certain cases barium chloride has been used as a flux for magnesium alloys; this is a significantly toxic substance and, consequently, considerable care is required in its use. Light alloys may occasionally be degassed by passing sulphur dioxide or chlorine (or proprietary compounds that decompose to produce chlorine) through the molten metal; exhaust ventilation and respiratory protective equipment are required for this operation. In order to reduce the cooling rate of the hot metal in the mould, a mixture of substances (usually aluminium and iron oxide) which react highly exothermically is placed on the mould riser. This “thermite” mixture gives off dense fumes which have been found to be innocuous in practice. When the fumes are brown in colour, alarm may be caused due to suspicion of the presence of nitrogen oxides; however, this suspicion is unfounded. The finely divided aluminium produced during the dressing of aluminium and magnesium castings constitutes a severe fire hazard, and wet methods should be used for dust collection.

Magnesium casting entails considerable potential fire and explosion hazard. Molten magnesium will ignite unless a protective barrier is maintained between it and the atmosphere; molten sulphur is widely employed for this purpose. Foundry workers applying the sulphur powder to the melting pot by hand may develop dermatitis and should be provided with gloves made of fireproof fabric. The sulphur in contact with the metal is constantly burning, so considerable quantities of sulphur dioxide are given off. Exhaust ventilation should be installed. Workers should be informed of the danger of a pot or ladle of molten magnesium catching fire, which may give rise to a dense cloud of finely divided magnesium oxide. Protective clothing of fireproof materials should be worn by all magnesium foundry workers. Clothing coated with magnesium dust should not be stored in lockers without humidity control, since spontaneous combustion may occur. The magnesium dust should be removed from the clothing.French chalk is used extensively in mould dressing in magnesium foundries; the dust should be controlled to prevent talcosis. Penetrating oils and dusting powders are employed in the inspection of light-alloy castings for the detection of cracks.

Dyes have been introduced to improve the effectiveness of these techniques. Certain red dyes have been found to be absorbed and excreted in sweat, thus causing soiling of personal clothing; although this condition is a nuisance, no effects on health have been observed.

Brass and bronze foundries

Toxic metal fumes and dust from typical alloys are a special hazard of brass and bronze foundries. Exposures to lead above safe limits in both melting, pouring and finishing operations are common, especially where alloys have a high lead composition. The lead hazard in furnace cleaning and dross disposal is particularly acute. Overexposure to lead is frequent in melting and pouring and can also occur in grinding. Zinc and copper fumes (the constituents of bronze) are the most common causes of metal fume fever, although the condition has also been observed in foundry workers using magnesium, aluminium, antimony and so on. Some high-duty alloys contain cadmium, which can cause chemical pneumonia from acute exposure and kidney damage and lung cancer from chronic exposure.

Permanent-mould process

Casting in permanent metal moulds, as in die-casting, has been an important development in the foundry. In this case, pattern making is largely replaced by engineering methods and is really a die-sinking operation. Most of the pattern making hazards are thereby removed and the risks from sand are also eliminated but are replaced by a degree of risk inherent in the use of some sort of refractory material to coat the die or mould. In modern die-foundry work, increasing use is made of sand cores, in which case the dust hazards of the sand foundry are still present.

Die casting

Aluminium is a common metal in die casting. Automotive hardware such as chrome trim is typically zinc die cast, followed by copper, nickel and chrome plating. The hazard of metal fume fever from zinc fumes should be constantly controlled, as must be chromic acid mist.

Pressure die-casting machines present all the hazards common to hydraulic power presses. In addition, the worker may be exposed to the mist of oils used as die lubricants and must be protected against the inhalation of these mists and the danger of oil-saturated clothing. The fire-resistant hydraulic fluids used in the presses may contain toxic organophosphorus compounds, and particular care should be taken during maintenance work on hydraulic systems.

Precision founding

Precision foundries rely on the investment or lost-wax casting process, in which patterns are made by injection moulding wax into a die; these patterns are coated with a fine refractory powder which serves as a mould-facing material, and the wax is then melted out prior to casting or by the introduction of the casting metal itself.

Wax removal presents a definite fire hazard, and decomposition of the wax produces acrolein and other hazardous decomposition products. Wax-burnout kilns must be adequately ventilated. Trichloroethylene has been used to remove the last traces of wax; this solvent may collect in pockets in the mould or be absorbed by the refractory material and vaporize or decompose during pouring. The inclusion of asbestos investment casting refractory materials should be eliminated due to the hazards of asbestos.

Health Problems and Disease Patterns

Foundries stand out among industrial processes because of a higher fatality rate arising from molten metal spills and explosions, cupola maintenance including bottom drop and carbon monoxide hazards during relining. Foundries report a higher incidence of foreign body, contusion and burn injuries and a lower proportion of musculoskeletal injuries than other facilities. They also have the highest noise exposure levels.

A study of several dozen fatal injuries in foundries revealed the following causes: crushing between mould conveyor cars and building structures during maintenance and trouble-shooting, crushing while cleaning mullers which were remotely activated, molten metal burns after crane failure, mould cracking, overflowing transfer ladle, steam eruption in undried ladle, falls from cranes and work platforms, electrocution from welding equipment, crushing from material-handling vehicles, burns from cupola bottom drop, high-oxygen atmosphere during cupola repair and carbon monoxide overexposure during cupola repair.

Abrasive wheels

The bursting or breaking of abrasive wheels may cause fatal or very serious injuries: gaps between the wheel and the rest at pedestal grinders may catch and crush the hand or forearm. Unprotected eyes are at risk at all stages. Slips and falls, especially when carrying heavy loads, may be caused by badly maintained or obstructed floors. Injuries to the feet may be caused by falling objects or dropped loads. Sprains and strains may result from overexertion in lifting and carrying. Badly maintained hoisting appliances may fail and cause materials to fall on workers. Electric shock may result from badly maintained or unearthed (ungrounded) electrical equipment, especially portable tools.

All dangerous parts of machinery, especially abrasive wheels, should have adequate guarding, with automatic lockout if the guard is removed during processing. Dangerous gaps between the wheel and the rest at pedestal grinders should be eliminated, and close attention should be paid to all precautions in the care and maintenance of abrasive wheels and in regulation of their speed (particular care is required with portable wheels). Strict maintenance of all electrical equipment and proper grounding arrangements should be enforced. Workers should be instructed in correct lifting and carrying techniques and should know how to attach loads to crane hooks and other hoisting appliances. Suitable PPE, such as eye and face shields and foot and leg protection, should also be provided. Provision should be made for prompt first aid, even for minor injuries, and for competent medical care when needed.

Dust

Dust diseases are prominent among foundry workers. Silica exposures are often close to or exceed prescribed exposure limits, even in well-controlled cleaning operations in modern production foundries and where castings are free of visible dust. Exposures many times above the limit occur where castings are dusty or cabinets leak. Overexposures are likely where visible dust escapes venting in shakeout, sand preparation or refractory repair.

Silicosis is the predominant health hazard in the steel fettling shop; a mixed pneumoconiosis is more prevalent in iron fettling (Landrigan et al. 1986). In the foundry, the prevalence increases with length of exposure and higher dust levels. There is some evidence that conditions in steel foundries are more likely to cause silicosis than those in iron foundries because of the higher levels of free silica present. Attempts to set an exposure level at which silicosis will not occur have been inconclusive; the threshold is probably less than 100 micrograms/m3 and perhaps as low as half that amount.

In most countries, the occurrence of new cases of silicosis is declining, in part because of changes in technology, a move away from silica sand in foundries and a shift away from silica brick and towards basic furnace linings in steel melting. A major reason is the fact that automation has resulted in the employment of fewer workers in steel production and foundries. Exposure to respirable silica dust remains stubbornly high in many foundries, however, and in countries where processes are labour intensive, silicosis remains a major problem.

Silico-tuberculosis has long been reported in foundry workers. Where the prevalence of silicosis has declined, there has been a parallel falling off in reported cases of tuberculosis, although that disease has not been completely eradicated. In countries where dust levels have remained high, dusty processes are labour intensive and the prevalence of tuberculosis in the general population is elevated, tuberculosis remains an important cause of death amongst foundry workers.

Many workers suffering from pneumoconiosis also have chronic bronchitis, often associated with emphysema; it has long been thought by many investigators that, in some cases at least, occupational exposures may have played a part. Cancer of the lung, lobar pneumonia, bronchopneumonia and coronary thrombosis have also been reported to be associated with pneumoconiosis in foundry workers.

A recent review of mortality studies of foundry workers, including the American auto industry, showed increased deaths from lung cancer in 14 of 15 studies. Because high lung cancer rates are found among cleaning room workers where the primary hazard is silica, it is likely that mixed exposures are also found.

Studies of the carcinogens in the foundry environment have concentrated on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons formed in the thermal breakdown of sand additives and binders. It has been suggested that metals such as chromium and nickel, and dusts such as silica and asbestos, may also be responsible for some of the excess mortality. Differences in moulding and core-making chemistry, sand type and the composition of iron and steel alloys may be responsible for different levels of risk in different foundries (IARC 1984).

Increased mortality from non-malignant respiratory disease was found in 8 of 11 studies. Silicosis deaths were recorded as well. Clinical studies found x-ray changes characteristic of pneumoconiosis, lung function deficits characteristic of obstruction, and increased respiratory symptoms among workers in modern “clean” production foundries. These resulted from exposures after the l960s and strongly suggest that the health risks prevalent in the older foundries have not yet been eliminated.

Prevention of lung disorders is essentially a matter of dust and fume control; the generally applicable solution is providing good general ventilation coupled with efficient LEV. Low-volume, high-velocity systems are most suitable for some operations, particularly portable grinding wheels and pneumatic tools.

Hand or pneumatic chisels used to remove burnt-on sand produce much finely divided dust. Brushing off excess materials with revolving wire brushes or hand brushes also produces much dust; LEV is required.

Dust control measures are readily adaptable to floor-standing and swing-frame grinders. Portable grinding on small castings can be carried out on exhaust-ventilated benches, or ventilation may be applied to the tools themselves. Brushing can also be carried out on a ventilated bench. Dust control on large castings presents a problem, but considerable progress has been made with low-volume, high-velocity ventilation systems. Instruction and training in their use is needed to overcome the objections of workers who find these systems cumbersome and complain that their view of the working area is impaired.

Dressing and fettling of very large castings where local ventilation is impracticable should be done in a separate, isolated area and at a time when few other workers are present. Suitable PPE that is regularly cleaned and repaired, should be provided for each worker, along with instruction in its proper use.

Since the 1950s, a variety of synthetic resin systems have been introduced into foundries to bind sand in cores and moulds. These generally comprise a base material and a catalyst or hardener which starts the polymerization. Many of these reactive chemicals are sensitizers (e.g., isocyanates, furfuryl alcohol, amines and formaldehyde) and have now been implicated in cases of occupational asthma among foundry workers. In one study, 12 out of 78 foundry workers exposed to Pepset (cold-box) resins had asthmatic symptoms, and of these, six had a marked decline in airflow rates in a challenge test using methyl di-isocyanate (Johnson et al. 1985).

Welding

Welding in fettling shops exposes workers to metal fumes with the consequent hazard of toxicity and metal fever, depending on the composition of the metals involved. Welding on cast iron requires a nickel rod and creates exposure to nickel fumes. The plasma torch produces a considerable amount of metal fumes, ozone, nitrogen oxide and ultraviolet radiation, and generates high levels of noise.

An exhaust-ventilated bench can be provided for welding small castings. Controlling exposures during welding or burning operations on large castings is difficult. A successful approach involves creating a central station for these operations and providing LEV through a flexible duct positioned at the point of welding. This requires training the worker to move the duct from one location to another. Good general ventilation and, when necessary, the use of PPE will aid in reducing the overall dust and fume exposures.

Noise and vibration

The highest levels of noise in the foundry are usually found in knockout and cleaning operations; they are higher in mechanized than in manual foundries. The ventilation system itself may generate exposures close to 90 dBA.

Noise levels in the fettling of steel castings may be in the range of 115 to 120 dBA, while those actually encountered in the fettling of cast iron are in the 105 to 115 dBA range. The British Steel Casting Research Association established that the sources of noise during fettling include:

- the fettling tool exhaust

- the impact of the hammer or wheel on the casting

- resonance of the casting and vibration against its support

- transmission of vibration from the casting support to surrounding structures

- reflection of direct noise by the hood controlling air flow through the ventilation system.

Noise control strategies vary with the size of the casting, the type of metal, the work area available, the use of portable tools and other related factors. Certain basic measures are available to reduce noise exposure of individuals and co-workers, including isolation in time and space, complete enclosures, partial sound-absorbing partitions, execution of work on sound-absorbing surfaces, baffles, panels and hoods made from sound-absorbing or other acoustical materials. The guidelines for safe daily exposure limits should be observed and, as a last resort, personal protective devices may be used.

A fettling bench developed by the British Steel Casting Research Association reduces the noise in chipping by about 4 to 5 dBA. This bench incorporates an exhaust system to remove dust. This improvement is encouraging and leads to hope that, with further development, even greater noise reductions will become possible.

Hand-arm vibration syndrome

Portable vibrating tools may cause Raynaud’s phenomenon (hand-arm vibration syndrome—HAVS). This is more prevalent in steel fettlers than in iron fettlers and more frequent among those using rotating tools. The critical vibratory rate for the onset of this phenomenon is between 2,000 and 3,000 revolutions per minute and in the range of 40 to 125 Hz.

HAVS is now thought to involve effects on a number of other tissues in the forearm apart from peripheral nerves and blood vessels. It is associated with carpal tunnel syndrome and degenerative changes in the joints. A recent study of steelworks chippers and grinders showed they were twice as likely to develop Dupuytren’s contracture than a comparison group (Thomas and Clarke 1992).

Vibration transmitted to the hands of the worker can be considerably reduced by: selection of tools designed to reduce the harmful ranges of frequency and amplitude; direction of the exhaust port away from the hand; use of multiple layers of gloves or an insulating glove; and shortening of exposure time by changes in work operations, tools and rest periods.

Eye problems

Some of the dusts and chemicals encountered in foundries (e.g., isocyanates, formaldehyde and tertiary amines, such as dimethlyethylamine, triethylamine and so on) are irritants and have been responsible for visual symptoms among exposed workers. These include itchy, watery eyes, hazy or blurred vision or so called “blue-grey vision”. On the basis of the occurrence of these effects, reducing time-weighted average exposures below 3 ppm has been recommended.

Other problems

Formaldehyde exposures at or above the US exposure limit are found in well-controlled hot-box core-making operations. Exposures many times above the limit may be found where hazard control is poor.

Asbestos has been used widely in the foundry industry and, until recently, it was often used in protective clothing for heat-exposed workers. Its effects have been found in x-ray surveys of foundry workers, both among production workers and maintenance workers who have been exposed to asbestos; a cross-sectional survey found the characteristic pleural involvement in 20 out of 900 steel workers (Kronenberg et al. 1991).

Periodic examinations

Preplacement and periodic medical examinations, including a survey of symptoms, chest x rays, pulmonary function tests and audiograms, should be provided for all foundry workers with appropriate follow-up if questionable or abnormal findings are detected. The compounding effects of tobacco smoke on the risk of respiratory problems among foundry workers mandate inclusion of advice on smoking cessation in a programme of health education and promotion.

Conclusion

Foundries have been an essential industrial operation for centuries. Despite continuing advances in technology, they present workers with a panoply of hazards to safety and health. Because hazards continue to exist even in the most modern plants with exemplary prevention and control programmes, protecting the health and well-being of workers remains an ongoing challenge to management and to the workers and their representatives. This remains difficult both in industry downturns (when concerns for worker health and safety tend to give way to economic stringencies) and in boom times (when the demand for increased output may lead to potentially dangerous short cuts in the processes). Education and training in hazard control, therefore, remain a constant necessity.

Forging and Stamping

Process Overview

Forming metal parts by application of high compressive and tensile forces is common throughout industrial manufacturing. In stamping operations, metal, most often in the form of sheets, strips or coils, is formed into specific shapes at ambient temperatures by shearing, pressing and stretching between dies, usually in a series of one or more discrete impact steps. Cold-rolled steel is the starting material in many stamping operations creating sheet metal parts in the automotive and appliance and other industries. Approximately 15% of workers in the automotive industry work in stamping operations or plants.

In forging, compressive force is applied to pre-formed blocks (blanks) of metal, usually heated to high temperatures, also in one or more discrete pressing steps. The shape of the final piece is determined by the shape of the cavities in the metal die or dies used. With open impression dies, as in drop hammer forging, the blank is compressed between one die attached to the bottom anvil and the vertical ram. With closed impression dies, as in press forging, the blank is compressed between the bottom die and an upper die attached to the ram.

Drop hammer forges use a steam or air cylinder to raise the hammer, which is then dropped by gravity or is driven by steam or air. The number and force of the hammer blows are manually controlled by the operator. The operator often holds the cold end of the stock while operating the drop hammer. Drop hammer forging once comprised about two-thirds of all forging done in the United States, but is less common today.

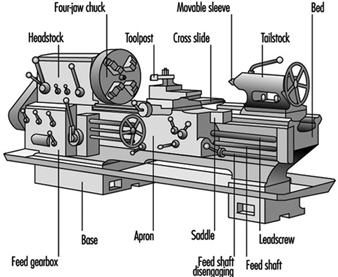

Press forges use a mechanical or hydraulic ram to shape the piece with a single, slow, controlled stroke (see figure 1). Press forging is usually controlled automatically. It can be done hot or at normal temperatures (cold-forging, extruding). A variation on normal forging is rolling, where continuous applications of force are used and the operator turns the part.

Figure 1. Press forging

Die lubricants are sprayed or otherwise applied to die faces and blank surfaces before and between hammer or press strokes.

High-strength machine parts such as shafts, ring gears, bolts and vehicle suspension components are common steel forging products. High-strength aircraft components such as wing spars, turbine disks and landing gear are forged from aluminium, titanium or nickel and steel alloys. Approximately 3% of automotive workers are in forging operations or plants.

Working Conditions

Many hazards common in heavy industry are present in stamping and forging operations. These include repetitive strain injuries (RSIs) from repeated handling and processing of parts and operation of machine controls such as palm buttons. Heavy parts place workers at risk for back and shoulder problems as well as upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Press operators in automotive stamping plants have rates of RSIs that are comparable to those of assembly plant workers in high-risk jobs. High-impulse vibration and noise are present in most stamping and some forging (e.g., steam or air hammer) operations, causing hearing loss and possible cardiovascular illness; these are among the highest-noise industrial environments (over 100 dBA). As in other forms of automation-driven systems, worker energy loads can be high, depending on the parts handled and machine cycling rates.

Catastrophic injuries resulting from unanticipated machine movements are common in stamping and forging. These can be due to: (1) mechanical failure of machine control systems, such as clutch mechanisms in situations where workers are routinely expected to be within the machine operating envelope (an unacceptable process design); (2) deficiencies in machine design or performance that invite unprogrammed worker interventions such as moving jammed or misaligned parts; or (3) improper, high-risk maintenance procedures performed without adequate lockout of the entire machine network involved, including parts transfer automation and the functions of other connected machines. Most automated machine networks are not configured for quick, efficient and effective lockout or safe trouble-shooting.

Mists from machine lubricating oils generated during normal operation are another generic health hazard in stamping and forging press operations powered by compressed air, potentially putting workers at risk for respiratory, dermatological and digestive diseases.

Health and Safety Problems

Stamping

Stamping operations have high risk of severe laceration due to the required handling of parts with sharp edges. Possibly worse is the handling of the scrap resulting from cut-off perimeters and punched out sections of parts. Scrap is typically collected by gravity-fed chutes and conveyors. Clearing occasional jams is a high-risk activity.

Chemical hazards specific to stamping typically arise from two main sources: drawing compounds (i.e., die lubricants) in actual press operations and welding emissions from assembly of the stamped parts. Drawing compounds (DCs) are required for most stamping. The material is sprayed or rolled onto sheet metal and further mists are generated by the stamping event itself. Like other metalworking fluids, drawing compounds may be straight oils or oil emulsions (soluble oils). Components include petroleum oil fractions, special lubricity agents (e.g., animal and vegetable fatty acid derivatives, chlorinated oils and waxes), alkanolamines, petroleum sulphonates, borates, cellulose-derived thickeners, corrosion inhibitors and biocides. Air concentrations of mist in stamping operations may reach those of typical machining operations, although these levels tend to be lower on average (0.05 to 2.0 mg/m3). However, visible fog and accumulated oil film on building surfaces are often present, and skin contact may be higher due to extensive handling of parts. Exposures most likely to present hazards are chlorinated oils (possible cancer, liver disease, skin disorders), rosin or tall oil fatty acid derivatives (sensitizers), petroleum fractions (digestive cancers) and, possibly, formaldehyde (from biocides) and nitrosamines (from alkanolamines and sodium nitrite, either as DC ingredients or in surface coatings on incoming steel). Elevated digestive cancer has been observed in two automotive stamping plants. Microbiological blooms in systems that apply DCs by rolling it onto sheet metal from an open reservoir can pose risks to workers for respiratory and dermatological problems analogous to those in machining operations.

Welding of stamped parts is often performed in stamping plants, usually without intermediate washing. This produces emissions that include metal fumes and pyrolysis and combustion products from drawing compound and other surface residues. Typical (primarily resistance) welding operations in stamping plants generate total particulate air concentrations in the range 0.05 to 4.0 mg/m3. Metal content (as fumes and oxides) usually makes up less than half of that particulate matter, indicating that up to 2.0 mg/m3 is poorly characterized chemical debris. The result is haze visible in many stamping plant welding areas. The presence of chlorinated derivatives and other organic ingredients raises serious concerns over the composition of welding smoke in these settings and strongly argues for ventilation controls. Application of other materials prior to welding (such as primer, paint and epoxy-like adhesives), some of which are then welded over, adds further concern. Welding production repair activities, usually done manually, often pose higher exposures to these same air contaminants. Excess rates of lung cancer have been observed among welders in an automotive stamping plant.

Forging

Like stamping, forging operations can pose high laceration risks when workers handle forged parts or trim the flash or unwanted edges off parts. High impact forging can also eject fragments, scale or tools, causing injury. In some forging activities, the worker grasps the working piece with tongs during the pressing or impact steps, increasing the risk for musculoskeletal injuries. In forging, unlike stamping, furnaces for heating parts (for forging and annealing) as well as bins of hot forgings are usually nearby. These create potential for high heat stress conditions. Additional factors in heat stress are the worker’s metabolic load during manual handling of materials and, in some cases, heat from combustion products of oil-based die lubricants.

Die lubrication is required in most forging and has the added feature that the lubricant comes in contact with high-temperature parts. This causes immediate pyrolysis and aerosolization not only in the dies but also subsequently from smoking parts in cooling bins. Forging die lubricant ingredients can include graphite slurries, polymeric thickeners, sulphonate emulsifiers, petroleum fractions, sodium nitrate, sodium nitrite, sodium carbonate, sodium silicate, silicone oils and biocides. These are applied as sprays or, in some applications, by swab. Furnaces used for heating metal to be forged are usually fired by oil or gas, or they are induction furnaces. Emissions can result from fuel-fired furnaces with inadequate draft and from non-ventilated induction furnaces when incoming metal stock has surface contaminants, such as oil or corrosion inhibitors, or if, prior to forging, it was lubricated for shearing or sawing (as in the case of bar stock). In the US, total particulate air concentrations in forging operations typically range from 0.1 to 5.0 mg/m3 and vary widely within forging operations due to thermal convection currents. An elevated lung cancer rate was observed among forging and heat treatment workers from two ball-bearing manufacturing plants.

Health and Safety Practices

Few studies have evaluated actual health effects in workers with stamping or forging exposures. Comprehensive characterization of the toxicity potential of most routine operations, including identification and measurement of priority toxic agents, has not been done. Evaluating the long-term health effects of die lubrication technology developed in the 1960s and 1970s has only recently become feasible. As a result, regulation of these exposures defaults to generic dust or total particulate standards such as 5.0 mg/m3 in the US. While probably adequate in some circumstances, this standard is not demonstrably adequate for many stamping and forging applications.

Some reduction in die lubricant mist concentrations is possible with careful management of the application procedure in both stamping and forging. Roll application in stamping is preferred when feasible, and using minimal air pressure in sprays is beneficial. Possible elimination of priority hazardous ingredients should be investigated. Enclosures with negative pressure and mist collectors can be highly effective but may be incompatible with parts handling. Filtering air released from high-pressure air systems in presses would reduce press oil mist (and noise). Skin contact in stamping operations can be reduced with automation and good personal protective wear, providing protection against both laceration and liquid saturation. For stamping plant welding, washing parts prior to welding is highly desirable, and partial enclosures with LEV would reduce smoke levels substantially.

Controls to reduce heat stress in stamping and hot forging include minimizing the amount of manual material handling in high-heat areas, shielding of furnaces to reduce radiation of heat, minimizing the height of furnace doors and slots and using cooling fans. The location of cooling fans should be an integral part of the design of air movement to control mist exposures and heat stress; otherwise, cooling may be obtained only at the expense of higher exposures.

Mechanization of material handling, switching from hammer to press forging when possible and adjusting the work rate to ergonomically practical levels can reduce the number of musculoskeletal injuries.

Noise levels can be reduced through a combination of switching from hammer to press forges when possible, well-designed enclosures and quieting of furnace blowers, air clutches, air leads and parts handling. A hearing conservation programme should be instituted.

PPE needed includes head protection, foot protection, goggles, hearing protectors (around are as with excessive noise), heat- and oil-proof aprons and leggings (with heavy use of oil-based die lubricants) and infrared eye and face protection (around furnaces).

Environmental Health Hazards

The environmental hazards arising from stamping plants, relatively minor compared to those from some other types of plants, include disposal of waste drawing compound and washing solutions and the exhausting of welding smoke without adequate cleaning. Some forging plants historically have caused acute degradation of local air quality with forging smoke and scale dust. However, with appropriate air cleaning capacity, this need not occur. Disposition of stamping scrap and forging scale containing die lubricants is another potential issue.

Welding and Thermal Cutting

This article is a revision of the 3rd edition of the Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety article “Welding and thermal cutting” by G.S. Lyndon.

Process Overview

Welding is a generic term referring to the union of pieces of metal at joint faces rendered plastic or liquid by heat or pressure, or both. The three common direct sources of heat are:

- flame produced by the combustion of fuel gas with air or oxygen

- electrical arc, struck between an electrode and a workpiece or between two electrodes

- electrical resistance offered to passage of current between two or more workpieces.

Other sources of heat for welding are discussed below (see table 1).

Table 1. Process materials inputs and pollution outputs for lead smelting and refining

|

Process |

Material input |

Air emissions |

Process wastes |

Other wastes |

|

Lead sintering |

Lead ore, iron, silica, limestone flux, coke, soda, ash, pyrite, zinc, caustic, baghouse dust |

Sulphur dioxide, particulate matter contain-ing cadmium and lead |

||

|

Lead smelting |

Lead sinter, coke |

Sulphur dioxide, particulate matter contain-ing cadmium and lead |

Plant washdown wastewater, slag granulation water |

Slag containing impurities such as zinc, iron, silica and lime, surface impoundment solids |

|

Lead drossing |

Lead bullion, soda ash, sulphur, baghouse dust, coke |

Slag containing such impurities as copper, surface impoundment solids |

||

|

Lead refining |

Lead drossing bullion |

In gas welding and cutting, oxygen or air and a fuel gas are fed to a blowpipe (torch) in which they are mixed prior to combustion at the nozzle. The blowpipe is usually hand held (see figure 1). The heat melts the metal faces of the parts to be joined, causing them to flow together. A filler metal or alloy is frequently added. The alloy often has a lower melting point than the parts to be joined. In this case, the two pieces are generally not brought to fusion temperature (brazing, soldering). Chemical fluxes may be used to prevent oxidation and facilitate the joining.

Figure 1. Gas welding with a torch & rod of filter metal. The welder is protected by a leather apron, gauntlets and goggles

In arc welding, the arc is struck between an electrode and the workpieces. The electrode can be connected to either an alternating current (AC) or direct current (DC) electric supply. The temperature of this operation is about 4,000°C when the workpieces fuse together. Usually it is necessary to add molten metal to the joint either by melting the electrode itself (consumable electrode processes) or by melting a separate filler rod which is not carrying current (non-consumable electrode processes).

Most conventional arc welding is done manually by means of a covered (coated) consumable electrode in a hand-held electrode holder. Welding is also accomplished by many semi or fully automatic electric welding processes such as resistance welding or continuous electrode feed.

During the welding process, the welding area must be shielded from the atmosphere in order to prevent oxidation and contamination. There are two types of protection: flux coatings and inert gas shielding. In flux-shielded arc welding, the consumable electrode consists of a metal core surrounded by a flux coating material, which is usually a complex mixture of mineral and other components. The flux melts as welding progresses, covering the molten metal with slag and enveloping the welding area with a protective atmosphere of gases (e.g., carbon dioxide) generated by the heated flux. After welding, the slag must be removed, often by chipping.

In gas-shielded arc welding, a blanket of inert gas seals off the atmosphere and prevents oxidation and contamination during the welding process. Argon, helium, nitrogen or carbon dioxide are commonly used as the inert gases. The gas selected depends upon the nature of the materials to be welded. The two most popular types of gas-shielded arc welding are metal- and tungsten inert gas (MIG and TIG).

Resistance welding involves using the electrical resistance to the passage of a high current at low voltage through components to be welded to generate heat for melting the metal. The heat generated at the interface between the components brings them to welding temperatures.

Hazards and Their Prevention

All welding involves hazards of fire, burns, radiant heat (infrared radiation) and inhalation of metal fumes and other contaminants. Other hazards associated with specific welding processes include electrical hazards, noise, ultraviolet radiation, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, fluorides, compressed gas cylinders and explosions. See table 2 for additional detail.

Table 2. Description and hazards of welding processes

|

Welding Process |

Description |

Hazards |

|

Gas welding and cutting |

||

|

Welding |

The torch melts the metal surface and filler rod, causing a joint to be formed. |

Metal fumes, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, noise, burns, infrared radiation, fire, explosions |

|

Brazing |

The two metal surfaces are bonded without melting the metal. The melting temperature of the filler metal is above 450 °C. Heating is done by flame heating, resistance heating and induction heating. |

Metal fumes (especially cadmium), fluorides, fire, explosion, burns |

|

Soldering |

Similar to brazing, except the melting temperature of the filler metal is below 450 °C. Heating is also done using a soldering iron. |

Fluxes, lead fumes, burns |

|

Metal cutting and flame gouging |

In one variation, the metal is heated by a flame, and a jet of pure oxygen is directed onto the point of cutting and moved along the line to be cut. In flame gouging, a strip of surface metal is removed but the metal is not cut through. |

Metal fumes, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, noise, burns, infrared radiation, fire, explosions |

|

Gas pressure welding |

The parts are heated by gas jets while under pressure, and become forged together. |

Metal fumes, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, noise, burns, infrared radiation, fire, explosions |

|

Flux-shielded arc welding |

||

|

Shielded metal arc welding (SMAC); “stick” arc welding; manual metal arc welding (MMA); open arc welding |

Uses a consumable electrode consisting of a metal core surrounded by a flux coating |

Metal fumes, fluorides (especially with low-hydrogen electrodes), infrared and ultraviolet radiation, burns, electrical, fire; also noise, ozone, nitrogen dioxide |

|

Submerged arc welding (SAW) |

A blanket of granulated flux is deposited on the workpiece, followed by a consumable bare metal wire electrode. The arc melts the flux to produce a protective molten shield in the welding zone. |

Fluorides, fire, burns, infrared radiation, electrical; also metal fumes, noise, ultraviolet radiation, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide |

|

Gas-shielded arc welding |

||

|

Metal inert gas (MIG); gas metal arc welding (GMAC) |

The electrode is normally a bare consumable wire of similar composition to the weld metal and is fed continuously to the arc. |

Ultraviolet radiation, metal fumes, ozone, carbon monoxide (with CO2 gas), nitrogen dioxide, fire, burns, infrared radiation, electrical, fluorides, noise |

|

Tungsten inert gas (TIG); gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW); heliarc |