Woodworking Processes

For the purposes of this article, the processes of the woodworking industry will be considered to start with the reception of converted timber from the sawmill and continue until the shipping of a finished wood article or product. Earlier stages in the handling of wood are dealt with in the chapters Forestry and Lumber industry.

The woodworking industry produces furniture and a variety of building materials, ranging from plywood floors to shingles. This article covers the main stages in the processing of wood for the production of wooden products, which are machine working of natural wood or manufactured panels, assembly of machined parts and surface finishing (e.g., painting, staining, lacquering, veneering and so on). Figure 1 is a flow diagram for wood furniture manufacturing, which covers nearly the whole range of these processes.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for wood furniture manufacturing

Drying. Some furniture manufacturing facilities may purchase dried lumber, but others perform drying onsite using a drying kiln or oven, fired by a boiler. Usually wood waste is the fuel.

Machining. Once the lumber is dried, it is sawed and otherwise machined into the shape of the final furniture part, such as a table leg. In a normal plant, the wood stock moves from rough planer, to cutoff saw, to rip saw, to finish planer, to moulder, to lathe, to table saw, to band saw, to router, to shaper, to drill and mortiser, to carver and then to a variety of sanders.

Wood can be hand carved/worked with a variety of hand tools, including chisels, rasps, files, hand saws, sandpaper and the like.

In many instances, the design of furniture pieces requires bending of certain wooden parts. This occurs after the planing process, and usually involves the application of pressure in conjunction with a softening agent, such as water, and increased atmospheric pressure. After bending into the desired shape, the piece is dried to remove excess moisture.

Assembly. Wood furniture can either be finished and then assembled, or the reverse. Furniture made of irregularly shaped components is usually assembled and then finished.

The assembly process usually involves the use of adhesives (either synthetic or natural) in conjunction with other joining methods, such as nailing, followed by the application of veneers. Purchased veneers are trimmed to correct size and patterns, and bonded to purchased chipboard.

After assembly, the furniture part is examined to ensure a smooth surface for finishing.

Pre-finishing. After initial sanding, an even smoother surface is attained by spraying, sponging or dipping the furniture part with water to cause the wood fibres to swell and “raise”. After the surface has dried, a solution of glue or resin is applied and allowed to dry. The raised fibres are then sanded down to form a smooth surface.

If the wood contains rosin, which can interfere with the effectiveness of certain finishes, it may be derosinated by applying a mixture of acetone and ammonia. The wood is then bleached by spraying, sponging or dipping the wood into a bleaching agent such as hydrogen peroxide.

Surface finishing. Surface finishing may involve the use of a large variety of coatings. These coatings are applied after the product is assembled or in a flat line operation before assembly. Coatings could normally include fillers, stains, glazes, sealers, lacquers, paints, varnishes and other finishes. The coatings may be applied by spray, brush, pad, dip, roller or flow-coating machine.

Coatings can be either solvent based or water based. Paints may contain a wide variety of pigments, depending on the desired colour.

Hazards and Precautions

Machining safety

Woodworking manufacturing has many of the hazards to safety and health that are common to general industry, with a much larger proportion of extremely hazardous equipment and operations than most. Consequently, safety requires constant attention to safe work habits by employees, vigilant supervision, and maintenance of a safe work environment by employers.

Although in many instances woodworking machinery and equipment may be purchased without the necessary guards and other safety devices, it is management’s responsibility to provide adequate safeguards before such machinery and equipment is used. See also the articles “Routing machines” and “Wood planing machines”.

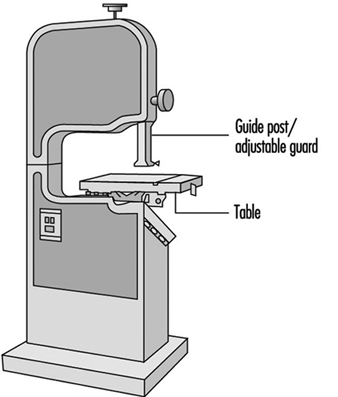

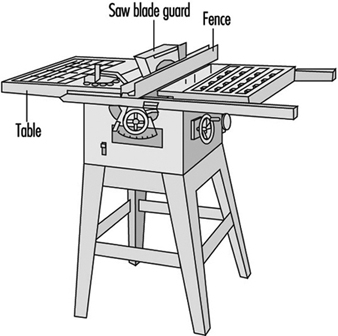

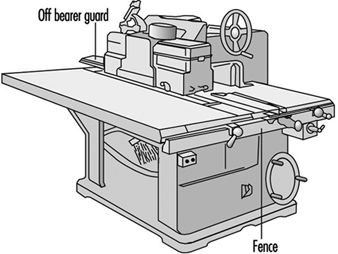

Sawing machines. Employees should be made aware of the safe operating practices necessary for the proper use of various woodworking saws (see figure 2 and figure 3).

Figure 2. Band saw

Specific guidelines are as follows:

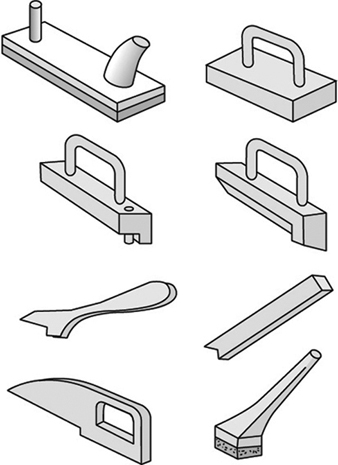

1. When feeding a table saw, hands must be kept out of the line of the cut. No guard can prevent a person’s hand from following the stock into the saw. When ripping with the fence gauge near the saw, a push stick or suitable jig must be used to complete the cut. See figure 4.

Figure 4. Push sticks

2. The saw blade must be positioned so as to minimize its protrusion above the stock; the lower the blade, the less chance for kickbacks. It is good practice to stand out of the line of the stock being ripped. A heavy leather apron or other guard for the abdomen is recommended.

3. Freehand sawing is always dangerous. The stock must always be held against a gauge or fence. See figure 3.

4. The saw must be appropriate for the job. For instance, it is an unsafe practice to rip with a table saw not equipped with a non-kickback device. Kickback aprons are recommended.

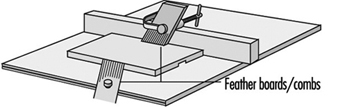

5. The dangerous practice of removing a hood guard because of narrow clearance on the gauge side can be avoided by clamping a filler board to the table between the gauge and the saw and using it to guide the stock. Employees must never be permitted to bypass guards. Combs, featherboards (see figure 5) or suitable jigs must be provided where standard guards cannot be used.

Figure 5. Featherboards & combs

6. Crosscutting long boards on a table saw should be avoided because the operator is required to use considerable hand pressure near the saw blade. Also, boards extending beyond the table may be struck by people or trucks. Long stock should be crosscut on a swing pull saw or radial arm saw with adequate supporting bench.

7. Work that should be done on special power-feed machines should not be done on general-purpose hand-fed machines.

8.To set a gauge of a table saw without taking off the guards, a permanent mark should designate the line of cut on the table top.

9. It is considered safe practice to bring equipment to a complete stop before adjusting blades or fences, and to disconnect the power source when changing blades.

10. A brush or stick should be used to clean sawdust and scrap from a saw.

A table saw is also called a variety saw because it can perform a wide variety of sawing functions. For this reason the operator should have a variety of guards, because no one guard can protect from every function. See figure 3.

Cutting machines. Cutting machines can also be hazardous if not adequately guarded and always used with respect and alertness. Cutting tools should be kept well sharpened and correctly balanced on their spindles.

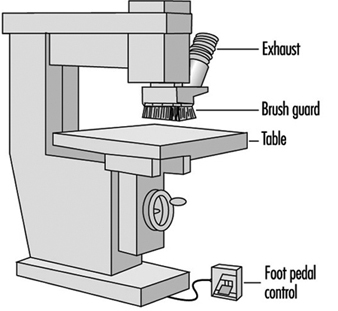

The router shown in figure 6 has a brush guard. Other routers may have a ring guard, a round guard that encircles the router bit. The purpose of guards is to keep the hands away from the cutting bit. Computer numerical controlled (CNC) routers may have several bits and are high production machines. On CNC machines the operator’s hands are kept further from the bit area. However, another problem is the high amount of wood dust. See also the article “Routing machines”.

Figure 6. Router

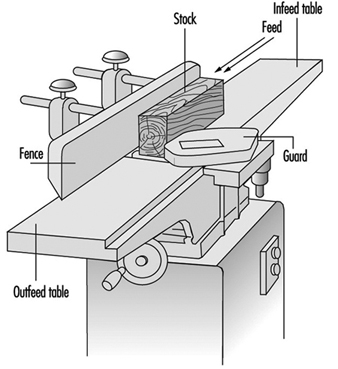

Guarding on a jointer or surface planing machine is mainly to keep the operator’s hands away from the revolving knives. The “mutton chop”-type guard allows only the portion of the knives which are cutting the stock to be exposed (see figure 7). The exposed portion of the knives behind the fence should also be guarded.

Figure 7. Jointer

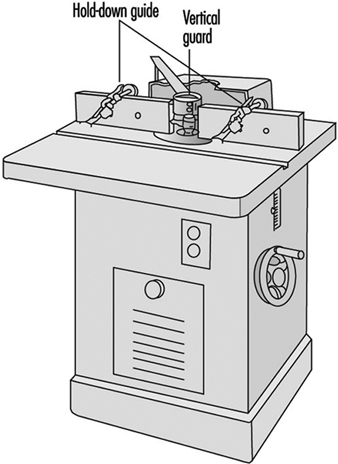

The shaper is a potentially very dangerous machine (see figure 8). If the shaper knives become separated from the above and below collars on the arbor, they can be thrown with great force. Also, stock must often be held close to the knives. This holding must be done with a fixture instead of by the operator’s hands. Featherboards can be used to hold the stock down against the table. Ring or saucer guards should be used whenever possible. A saucer guard is a round, flat, plastic disk that is mounted horizontally on the arbor above the shaper knives.

Figure 8. Shaper

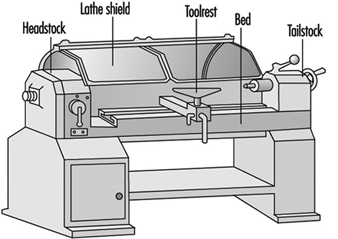

A lathe should be guarded by a hood guard because there is a danger of the stock being thrown from the machine. See figure 9. It is good practice for the hood to be interlocked with the motor so the lathe cannot be run unless the hood guard is in place.

Figure 9. Lathe

A ripsaw should have anti-kickback fingers installed to prevent the stock from reversing its direction and striking the operator. See figure 10. Also, the operator should wear a padded apron to lessen the impact if a kickback does occur.

Figure 10. Ripsaw

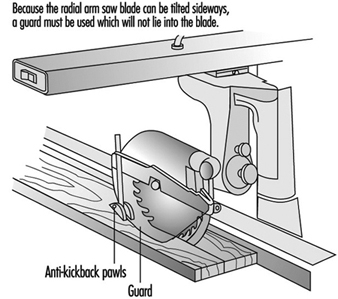

Because the radial arm saw blade can be tilted sideways, a guard must be used which will not lie into the blade. See figure 11.

Figure 11. Radial arm saw

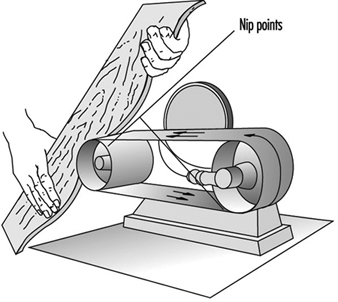

Sanding machines. Machined stock pieces are sanded down using belt, jitterbug, disc, drum or orbital sanders. Nip points are created in sanding belts. See figure 12. Often these nip points can be guarded with a hood which will also be part of a dust exhaust system.

Figure 12. Sander

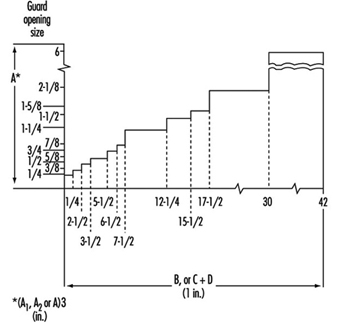

Machine guarding. Figure 13 illustrates that the opening between a guard and the point of contact must be decreased as the distance decreases.

Figure 13. Distance between guard & point of operation

Miscellaneous machine safety concerns. Care must be taken that the use of stock-clamping/holding devices do not create additional hazards.

Most woodworking machines create the necessity of the operator (and helper) wearing eye protection.

It is common practice for employees to blow dust off of themselves with compressed air. They should be cautioned to keep air pressure below 30 psi and to avoid blowing into eyes or open cuts.

Wood dust hazards

Machines that produce wood dust should be equipped with dust-collecting systems. If the exhaust system is inadequate to dispose of the wood dust, the operator may need to wear a dust respirator. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has now determined that “there is sufficient evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of wood dust”, and that “Wood dust is carcinogenic to humans (Group 1)”. Other studies indicate that wood dust may prove an irritant to the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose and throat. Some toxic woods are more actively pathogenic and may produce allergic reactions and occasionally pulmonary disorders and systemic poisoning. See table 1.

Table 1. Poisonous, allergenic and biologically active wood varieties

|

Scientific names |

Selected commercial names |

Family |

Health Impairment |

|

Abies alba Mill (A. pectinata D.C.) |

Silver fir |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Acacia spp. |

Australian blackwood |

Mimosaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Acer spp. |

Maple |

Aceraceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Afrormosia elata Harms. |

Afrormosia, kokrodua, asamala, obang, oleo pardo, bohele, mohole |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Afzelia africana Smith |

Doussié, afzelia, aligua, apa, chanfuta, lingue merbau, intsia, hintsy |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Agonandra brasiliensis Miers |

Pao, marfim, granadillo |

Olacaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Ailanthus altissima Mill |

Chinese sumac |

Simaroubaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Albizzia falcata Backer |

Iatandza |

Mimosaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; |

|

Alnus spp. |

Common alder |

Betulaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Amyris spp. |

Venezuelan or West Indian sandalwood |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Anacardium occidentale L. |

Cashew |

Anacardiaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Andira araroba Aguiar. (Vataireopsis araroba Ducke) |

Red cabbage tree |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Aningeria spp. |

Aningeria |

Sapotaceae |

Conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Apuleia molaris spruce (A. leiocarpa MacBride) |

Redwood |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Araucaria angustifolia O. Ktze |

Parana pine, araucaria |

Araucariaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Aspidosperma spp. |

Red peroba |

Apocynaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis- |

|

Astrocaryum spp. |

Palm |

Palmaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Aucoumea klaineana Pierre |

Gabon mahogany |

Burseraceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Autranella congolensis |

Mukulungu, autracon, elang, bouanga, kulungu |

Sapotaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Bactris spp. (Astrocaryum spp.) |

Palm |

Palmaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Balfourodendron riedelianum Engl. |

Guatambu, gutambu blanco |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Batesia floribunda Benth. |

Acapu rana |

Caesalpinaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Berberis vulgaris L. |

Barberry |

Berberidaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Betula spp. |

Birch |

Betulaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Blepharocarva involucrigera F. Muell. |

Rosebutternut |

Anacardiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Bombax brevicuspe Sprague |

Kondroti, alone |

Bombacaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Bowdichia spp. |

Black sucupira |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Brachylaena hutchinsii Hutch. |

Muhuhu |

Compositae |

Dermatitis |

|

Breonia spp. |

Molompangady |

Rubiaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Brosimum spp. |

Snakewood, letterwood, tigerwood |

Moraceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Brya ebenus DC. (Amerimnum ebenus Sw.) |

Brown ebony, green ebony, Jamaican ebony, tropical American ebony |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Buxus sempervirens L. |

European boxwood, East London b., Cape b. |

Buxaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Caesalpinia echinata Lam. (Guilandina echinata Spreng.) |

Brasilwood |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Callitris columellaris F. Muell. |

White cypress pine |

Cupressaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Calophyllum spp. |

Santa maria, jacareuba, kurahura, galba |

Guttiferae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Campsiandra laurifolia Benth. |

Acapu rana |

Caesalpinaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Carpinus betulus |

Hornbeam |

Betulaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Cassia siamea Lamk. |

Tagayasan, muong ten, djohar |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Castanea dentata Borkh |

Chestnut, sweet chestnut |

Fagaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Castanospermum australe A. Cunn. |

Black bean, Australian or Moreton Bay chestnut |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Cedrela spp. (Toona spp.) |

Red cedar, Australian cedar |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex. Lamb.) G. Don |

Deodar |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Celtis brieyi De Wild. |

Diania |

Ulmaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Chlorophora excelsa Benth. and Hook I. |

Iroko, gelbholz, yellowood, kambala, mvule, odum, moule, African teak, abang, tatajuba, fustic, mora |

Moraceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Chloroxylon spp. |

Ceylon satinwood |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Chrysophyllum spp. |

Najara |

Sapotaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Cinnamomum camphora Nees and Ebeim |

Asian camphorwood, cinnamon |

Lauraceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Cryptocarya pleurosperma White and Francis |

Poison walnut |

Lauraceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Dacrycarpus dacryoides (A. Rich.) de Laub. |

New Zealand white pine |

Podocarpaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Dacrydium cupressinum Soland |

Sempilor, rimu |

Podocarpaceae |

conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Dactylocladus stenostachys Oliv. |

Jong kong, merebong, medang tabak |

Melastomaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Dalbergia spp. |

Ebony |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; |

|

Dialium spp. |

Eyoum, eyum |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Diospyros spp. |

Ebony, African ebony |

Ebenaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Dipterocarpus spp. |

Keruing, gurjum, yang, keruing |

Dipterocarpaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Distemonanthus benthamianus Baill. |

Movingui, ayan, anyaran, Nigerian satinwood |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Dysoxylum spp. |

Mahogany, stavewood, red bean |

Meliaceae |

dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

D. muelleri Benth. |

Rose mahogany |

||

|

Echirospermum balthazarii Fr. All. (Plathymenia reticulata Benth.) |

Vinhatico |

Mimosaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Entandophragma spp. |

Tiama |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; |

|

Erythrophloeum guineense G. Don |

Tali, missanda, eloun, massanda, sasswood, erun, redwater tree |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Esenbeckia leiocarpa Engl. |

Guaranta |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Eucalyptus spp. |

|

Myrtaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Euxylophora paraensis Hub. |

Boxwood |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Excoecaria africana M. Arg. (Spirostachys africana Sand) |

African sandalwood, tabootie, geor, aloewood, blind-your-eye |

Euphorbiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Fagara spp. |

Yellow sanders, West Indian satinwood, atlaswood, olon, bongo, mbanza |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Fagus spp. (Nothofagus spp.) |

Beech |

Fagaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Fitzroya cupressoides (Molina) Johnston |

Alerce |

Cupressaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Flindersia australis R. Br. |

Australian teak, Queensland maple, maple |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Fraxinus spp. |

Ash |

Oleaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Gluta spp. |

Rengas, gluta |

Anacardiaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Gonioma kamassi E. Mey. |

Knysna boxwood, kamassi |

Apocynaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Gonystylus bancanus Baill. |

Ramin, melawis, akenia |

Gonystylaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Gossweilerodendron balsamiferum (Verm.) Harms. |

Nigerian cedar |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Grevillea robusta A. Cunn. |

Silky oak |

Proteaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Guaiacum officinale L. |

Gaiac, lignum vitae |

Zygophyllaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Guarea spp. |

Bossé |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Halfordia scleroxyla F. Muell. |

Saffron-heart |

Polygonaceae |

Dermatitis; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Hernandia spp. |

Mirobolan, topolite |

Hernandiaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Hippomane mancinella L. |

Beach apple |

Euphorbiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Illipe latifolia F. Muell. |

Moak, edel teak |

Sapotaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Jacaranda spp. |

Jacaranda |

Bignoniaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Juglans spp. |

Walnut |

Juglandaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Juniperus sabina L. |

|

Cupressaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Khaya antotheca C. DC. |

Ogwango, African mahogany, krala |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Laburnum anagyroides Medic. (Cytisus laburnum L.) |

Laburnum |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Larix spp. |

Larch |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Liquidambar styracifolia L. |

Amberbaum, satin-nussbaum |

Hamamelidaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Liriodendron tulipifera L. |

American whitewood, tulip tree |

Magnoliaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Lovoa trichilioides Harms. (L. klaineana Pierre) |

Dibetou, African walnut, apopo, tigerwood, side |

Meliaceae |

dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Lucuma spp. (Pouteria spp.) |

Guapeva, abiurana |

Sapotaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Maba ebenus Wight. |

Makassar-ebenholz |

Ebenaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Machaerium pedicellatum Vog. |

Kingswood |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Mansonia altissima A. Chev. |

Nigerian walnut |

Sterculiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Melanoxylon brauna Schott |

Brauna, grauna |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Microberlinia brazzavillensis A. Chev. |

African zebrawood |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Millettia laurentii De Wild. |

Wenge |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; |

|

Mimusops spp. (Manilkara spp.) |

Muirapiranga |

Sapotaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; |

|

Mitragyna ciliata Aubr. and Pell. |

Vuku, African poplar |

Rubiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; |

|

Nauclea diderrichii Merrill (Sarcocephalus diderrichii De Wild.) |

Bilinga, opepe, kussia, badi, West African boxwood |

Rubiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Nesogordonia papaverifera R. Capuron |

Kotibé, danta, epro, otutu, ovové, aborbora |

Tiliaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Ocotea spp. |

Stinkwood |

Lauraceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Paratecoma spp. |

|

Bignoniaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Parinarium spp. |

|

Rosaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Peltogyne spp. |

Blue wood, purpleheart |

Caesalpinaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Phyllanthus ferdinandi F.v.M. |

Lignum vitae, chow way, tow war |

Euphorbiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Picea spp. |

European spruce, whitewood |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Pinus spp. |

Pine |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Piptadenia africana Hook f. |

Dabema, dahoma, ekhimi |

Mimosaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Platanus spp. |

Plane |

Platanaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Pometia spp. |

Taun |

Sapindaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Populus spp. |

Poplar |

Salicaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Prosopis juliflora D.C. |

Cashaw |

Mimosaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Prunus spp. |

Cherry |

Rosaceae |

dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Pseudomorus brunoniana Bureau |

White handlewood |

Moraceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Pseudotsuga douglasii Carr. (P. menziesii Franco) |

Douglas fir, red fir, Douglas spruce |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Pterocarpus spp. |

African padauk, New Guinea rosewood, red sandalwood, red sanders, quassia wood |

Papilionaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Pycnanthus angolensis Warb. (P. kombo Warb.) |

Ilomba |

Myristicaceae |

Toxic effects |

|

Quercus spp. |

Oak |

Fagaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Raputia alba Engl. |

Arapoca branca, arapoca |

Rutaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Rauwolfia pentaphylla Stapf. O. |

Peroba |

Apocynaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Sandoricum spp. |

Sentul, katon, kra-ton, ketjapi, thitto |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Schinopsis lorentzii Engl. |

Quebracho colorado, red q., San Juan, pau mulato |

Anacardiaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Semercarpus australiensis Engl. |

Marking nut |

Anacardiaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

|

Sequoia sempervirens Endl. |

Sequoia, California |

Taxodiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Shorea spp. |

Alan, almon, red balau |

Dipterocarpaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

S. assamica Dyer |

Yellow lauan, white meranti |

||

|

Staudtia stipitata Warb. (S. gabonensis Warb.) |

Niové |

Myristicaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Swietenia spp. |

Mahogany, Honduras mahogany, Tabasco m., baywood, American mahogany, |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis; toxic effects |

|

Swintonia spicifera Hook. |

Merpauh |

Anacardiaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Tabebuia spp. |

Araguan, ipé preto, lapacho |

Bignoniaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Taxus baccata L. |

Yew |

Taxaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis; toxic effects |

|

Tecoma spp. |

Green heart |

Bignoniaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Tectona grandis L. |

Teak, djati, kyun, teck |

Verbenaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Terminalia alata Roth. |

Indian laurel |

Combretaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Thuja occidentalis L. |

White cedar |

Cupressaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Tieghemella africana A. Chev. (Dumoria spp.) |

Makoré, douka, okola, ukola, makoré, abacu, baku, African cherry |

Sapotaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma; toxic effects |

|

Triplochiton scleroxylon K. Schum |

Obeche, samba, wawa, abachi, African whitewood, arere |

Sterculiaceae |

Dermatitis; conjunctivitis-rhinitis; asthma |

|

Tsuga heterophylla Sarg. |

Tsuga, Western hemlock |

Pinaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Turraeanthus africana Pell. |

Avodiré |

Meliaceae |

Dermatitis; allergic extrinsic alveolitis |

|

Ulmus spp. |

Elm |

Ulmaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

Vitex ciliata Pell. |

Verbenaceae |

Dermatitis |

|

|

V. congolensis De Wild. and Th. Dur |

Difundu |

||

|

V. pachyphylla Bak. |

Evino |

||

|

Xylia dolabriformis Benth. |

Mimosaceae |

Conjunctivitis-rhinitis; |

|

|

X. xylocarpa Taub. |

Pyinkado |

asthma |

|

|

Zollernia paraensis Huber |

Santo wood |

Caesalpinaceae |

Dermatitis; toxic effects |

Source: Istituto del Legno, Florence, Italy.

Increased use of high-production CNC machinery such as routers, tenoners and lathes creates more wood dust and will require new dust-collection technology.

Dust control. Most dust in a woodworking production shop is removed by local exhaust systems. However, often there is a considerable accumulation of very fine dust that has settled on rafters and other structural members, especially in areas where sanding is done. This is a hazardous situation, with great potential for fire and explosion. A flash fire over dust-covered surfaces may be followed by explosions of increasing force. In order to minimize this probability, it would be wise to use a checklist. See sample checklist in box.

Assembly hazards

A wide range of adhesives is used in the bonding of veneers to manufactured panels, depending on the characteristics required of the final product. Apart from casein glue, natural adhesives are less widely employed and the greatest use is made of synthetic adhesives such as urea-formaldehyde. Synthetic adhesives may pose a hazard of skin disease or systemic intoxication, especially those which release free formaldehyde or organic solvents into the atmosphere. Adhesives should be handled in well ventilated premises and sources of vapour emission should be equipped with exhaust ventilation. Employees should be provided with gloves, protective creams, respirators and eye protection when necessary.

The moving parts, especially blades, of veneer slicing, jointing and clipping machines should be fully guarded. Two-hand controls may be necessary.

Finishing hazards

Surface finishing. Solvents used for carrying the sprayed pigments or for thinning can include a wide variety of volatile organic compounds which may reach toxic and explosive concentrations in the air. In addition, many pigments are toxic by inhalation of spray mist (e.g., lead, manganese and cadmium pigments). Wherever dangerous concentrations of vapour or mist can occur, use exhaust ventilation (e.g., spray painting in a booth) or use water sprays. All sources of ignition, including fires, electrical equipment and static electricity, should be eliminated before any operations begin.

An active hazardous material communication programme should be in place to alert employees to all hazards created by toxic, reactive, corrosive and/or ignitable finish, glue and solvent chemicals and the protective measures that should be taken. Eating in the presence of these chemicals should be prohibited. Proper storage of flammables and proper disposal of soiled rags and steel wool which could cause spontaneous ignition are imperative.

Fire prevention. In view of the highly flammable nature of wood (especially in the form of dust and shavings) and of the other items found in a woodworking plant (such as solvents, glues and coatings), the importance of fire prevention measures cannot be overemphasized. Measures include:

- installing automatic wood-dust and shaving collection equipment on saws, planers, moulders and so on, which transport the waste to storage silos pending disposal or recovery

- prohibiting smoking at the workplace and eliminating all sources of ignition (e.g., open flames)

- ensuring regular clean-up procedures of deposited dust and shavings

- adequate maintenance of machines to prevent occurrences such as the overheating of bearings

- installation of fire barriers, sprinkler systems, fire extinguishers, fire hoses and a crew trained to use this equipment

- proper storage of flammables

- explosion-proof electrical equipment where needed.

Environmental and Public Health Concerns

The production of finished products from wood can be done without long-range environmental damage. The harvesting of trees can be done in such a manner that new growth can replace what is cut. Major deforestation such as has been the case in rain forests can be discouraged. Waste products from the machining of wood (i.e., sawdust, wood chips) can be used in chipcore or as fuel.

While there are solid waste and process wastewater implications for the woodworking industry, the major concerns are the air emissions resulting from the use of waste wood as fuel and from solvent-intensive finishing operations. Wood-fired boilers are commonly used in drying operations, while many of the finishing materials are applied by spray. In both instances, engineering controls are required to reduce air-borne particulates and recover and/or incinerate the volatile compounds.

Controls should result in operators being exposed to less toxic chemicals as less hazardous substitutes are found. Use of water-based finishes instead of solvent-based will decrease fire hazards.

General Profile

Traditionally, furniture factories have been located in Europe and North America. With the increased cost of labour in industrialized countries, more furniture production, which is labour intensive, has shifted to Far Eastern countries. It is likely that this movement will continue unless more automated equipment can be developed.

Most furniture manufacturers are small enterprises. For example, in the United States, approximately 86% of the factories in the wood furniture industry have fewer than 50 employees (EPA 1995); this is representative of the situation internationally.

The woodworking industry in the United States is responsible for manufacturing household, office, store, public building and restaurant furniture and fixtures. The woodworking industry falls under the US Bureau of the Census Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Code 25 (equivalent to International SIC Code 33) and includes: wood household furniture, such as beds, tables, chairs and bookshelves; wood television and radio cabinets; wood office furniture, such as cabinets, chairs and desks; and wood office and store fixtures and partitions, such as bar fixtures, counters, lockers and shelves.

Because production lines for assembling furniture are costly, most manufacturers do not supply an exceptionally large range of items. Manufacturers may specialize in the product manufactured, the product group or the production process (EPA 1995).

Commercial Photographic Laboratories

Materials and Processing Operations

Black-and-white processing

In black-and-white photographic processing, exposed film or paper is removed from a light-tight container in a darkroom and sequentially immersed in water solutions of developer, stop bath and fixer. After a water washing, the film or paper is dried and ready for use. The developer reduces the light-exposed silver halide to metallic silver. The stop bath is a weakly acidic solution that neutralizes the alkaline developer and stops further reduction of the silver halide. The fixer solution forms a soluble complex with the unexposed silver halide, which is subsequently removed from the emulsion in the washing process together with various water-soluble salts, buffers and halide ions.

Colour processing

Colour processing is more complex than black-and-white processing, with additional steps required for processing most types of colour film, transparencies and paper. In short, instead of one silver halide layer, as in black-and-white films, there are three superimposed silver negatives; that is, a silver negative is produced for each of three sensitized layers. On contact with the colour developer, the exposed silver halide is converted to metallic silver while the oxidized developer reacts with a specific coupler in each layer to form the dye image.

Another difference in colour processing is the use of a bleach to remove the unwanted metallic silver from the emulsion by converting metallic silver to silver halide by means of an oxidizing agent. Subsequently, the silver halide is converted to a soluble silver complex, which is then removed by washing as in the case of black-and-white processing. In addition, colour processing procedures and materials vary depending on whether a colour transparency is being formed or whether colour negatives and colour prints are being processed.

General processing design

The essential steps in photoprocessing thus consist of passing the exposed film or paper through a series of processing tanks either by hand or in machine processors. Although the individual processes may be different, there are similarities in the types of procedures and equipment used in photoprocessing. For example, there will be a storage area for chemicals and raw materials and facilities for handling and sorting incoming exposed photographic materials. Facilities and equipment are necessary for measuring, weighing and mixing processing chemicals, and for supplying these solutions to the various processing tanks. In addition, a variety of pumping and metering devices are used to deliver processing solutions to tanks. A professional or photofinishing laboratory will typically utilize larger, more automated equipment that will process either film or paper. To produce a consistent product, the processors are temperature controlled and, in most cases, are replenished with fresh chemicals as sensitized product is run through the processor.

Larger operations may have quality-control laboratories for chemical determinations and measurement of photographic quality of materials being produced. Although the use of packaged chemical formulations may eliminate the need for measuring, weighing and maintaining a quality-control laboratory, many large photoprocessing facilities prefer to mix their own processing solutions from bulk quantities of the constituent chemicals.

Following the processing and drying of materials, protective lacquers or coatings may be applied to the finished product, and film-cleaning operations may take place. Finally, materials are inspected, packaged and prepared for shipment to the customer.

Potential Hazards and their Prevention

Unique darkroom hazards

The potential hazards in commercial photographic processing are similar to those in other types of chemical operations; however, a unique feature is the requirement that certain portions of the processing operations be conducted in darkness. Consequently, the processing operator must have a good understanding of the equipment and its potential hazards, and of precautionary measures in case of accidents. Safelights or infrared goggles are available and can be used to provide sufficient illumination for operator safety. All mechanical elements and live electrical parts must be enclosed and projecting machine parts must be covered. Safety locks should be installed to ensure that light does not enter the darkroom and should be designed so that they allow free passage of personnel.

Skin and eye hazards

Because of the wide variety of formulae used by various suppliers and different methods of packaging and mixing photoprocessing chemicals, only a few generalizations can be made regarding the types of chemical hazards present. A variety of strong acids and caustic materials may be encountered, especially in storage and mixing areas. Many photoprocessing chemicals are skin and eye irritants and, in some cases, may cause skin or eye burns following direct contact. The most frequent health issue in photoprocessing is the potential for contact dermatitis, which most commonly arises from skin contact with alkaline developer solutions. The dermatitis may be due to irritation caused by alkaline or acidic solutions, or, in some cases, to skin allergy.

Colour developers are aqueous solutions that usually contain derivatives of p-phenylenediamine, whereas black-and-white developers usually contain p-methyl-aminophenolsulphate (also known as Metol or KODAK ELON Developing Agent) and/or hydroquinone. Colour developers are more potent skin sensitizers and irritants than black-and-white developers and may also cause lichenoid reactions. In addition, other skin sensitizers such as formaldehyde, hydroxylamine sulphate and S-(2-(dimethylamino)-ethyl)-isothiouronium dihydrochloride are found in some photoprocessing solutions. The development of skin allergy is more likely to occur after repeated and prolonged contact with processing solutions. Persons with pre-existing skin diseases or skin irritation are often more susceptible to the effects of chemicals on the skin.

Avoiding skin contact is an important goal in photoprocessing areas. Neoprene gloves are recommended for reducing skin contact, especially in the mixing areas, where more concentrated solutions are encountered. Alternatively, nitrile gloves may be used when prolonged contact with photochemicals is not required. Gloves should be of sufficient thickness to prevent tears and leaks, and should be inspected and cleaned frequently, preferably by thorough washing of the outer and inner surfaces with a non-alkaline hand cleaner. It is particularly important that maintenance personnel be provided with protective gloves during repair or cleaning of the tanks and rack assemblies, and so on, since these may become coated with deposits of chemicals. Barrier creams are not appropriate for use with photochemicals because they are not impervious to all photochemicals and may contaminate processing solutions. A protective apron or lab coat should be worn in the darkroom, and frequent laundering of work clothing is desirable. For all reusable protective clothing, users should look for signs of permeation or degradation after each use and replace clothing as appropriate. Protective goggles and a face shield also should be used, especially in areas where concentrated photochemicals are handled.

If photoprocessing chemicals contact the skin, the affected area should be flushed quickly with copious amounts of water. Because materials such as developers are alkaline, washing with a non-alkaline hand cleaner (pH of 5.0 to 5.5) reduces the potential to develop dermatitis. Clothing should be changed immediately if there is any contamination with chemicals, and spills or splashes should be immediately cleaned up. Hand-washing facilities and provisions for rinsing the eyes are particularly important in the mixing and processing areas. Emergency shower facilities should also be available.

Inhalation hazards

In addition to potential skin and eye hazards, gases or vapours emitted from some photoprocessing solutions may present an inhalation hazard, as well as contribute to unpleasant odours, especially in poorly ventilated areas. Some colour processing solutions may release vapours such as acetic acid, triethanolamine and benzyl alcohol, or gases such as ammonia, formaldehyde and sulphur dioxide. These gases or vapours may be irritating to the respiratory tract and eyes, or, in some cases, may cause other health-related effects. The potential health-related effects of these gases or vapours is concentration dependent and is usually observed only at concentrations that exceed occupational exposure limits. However, because of a wide variation in individual susceptibility, some individuals—for example, persons with pre-existing medical conditions such as asthma—may experience effects at concentrations below occupational exposure limits.

Some photochemicals may be detectable by odour because of the chemical’s low odour threshold. Although the odour of a chemical is not necessarily indicative of a health hazard, strong odours or odours that are increasing in intensity may indicate that the ventilation system is inadequate and should be reviewed.

Appropriate photoprocessing ventilation incorporates both general dilution and local exhaust to exchange air at an acceptable rate per hour. Good ventilation offers the added benefit of making the working environment more comfortable. The amount of ventilation required varies according to room conditions, processing output, specific processors and processing chemicals. A ventilation engineer may be consulted to ensure optimum operation of room and local exhaust ventilation systems. High-temperature processing and nitrogen-burst agitation of tank solutions may increase the release of some chemicals to the ambient air. Processor speed, solution temperatures and solution agitation should be set at minimum suitable performance levels to reduce the potential release of gases or vapours from processing tanks.

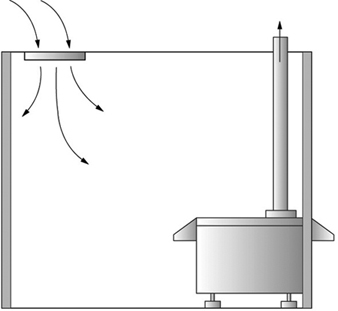

General room ventilation—for example, 4.25 m3/min supply and 4.8 m3/min exhaust (equivalent to 10 air changes per hour in a 3 x 3 x 3-metre room), with a minimum outside air replenishment rate of 0.15 m3/min per m2 floor area—is usually adequate for photographers who undertake basic photoprocessing. An exhaust rate higher than a supply rate produces a negative pressure in the room and reduces the opportunity for gases or vapours to escape to adjoining areas. The exhaust air should be discharged outside the building to avoid redistributing potential air contaminants within the building. If the processor tanks are enclosed and have an exhaust (see figure 1), the minimum air supply and exhaust rate can probably be reduced.

Figure 1. Enclosed-machine ventilation

Some operations (e.g., toning, film cleaning, mixing operations and special processing procedures) may require supplementary local exhaust ventilation or respiratory protection. Local exhaust is important because it reduces the concentration of airborne contaminants that might otherwise be recirculated by the general dilution ventilation system.

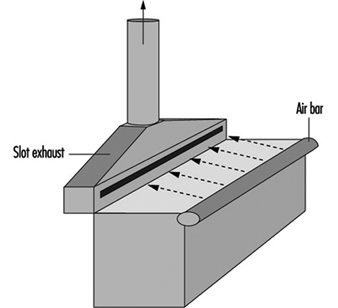

A lateral slot-type ventilation system for extracting vapours or gases at the surface of a tank may be used for some tanks. When designed and operated correctly, lateral slot-type exhausts draw clean air across the tank and remove contaminated air from the operator’s breathing zone and the surface of the processing tanks. Push-pull lateral slot-type exhausts are the most effective systems (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Open-tank with "push-pull" ventilation

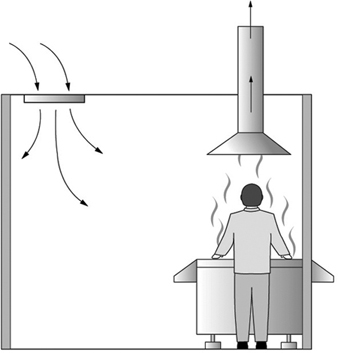

A hooded or canopy exhaust system (see figure 3) is not recommended because operators often lean over tanks with their heads under the hood. In this position, the hood draws vapours or gases into the operator’s breathing zone.

Figure 3. Overhead canopy exhaust

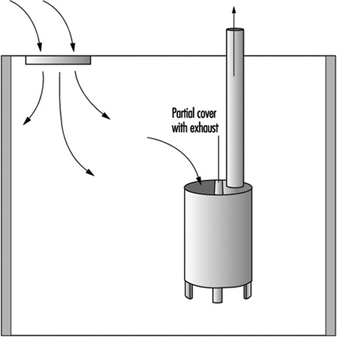

Split-tank covers with local exhaust attached to the stationary portion on mixing tanks may be used to supplement general room ventilation in mixing areas. Tank covers (tight-fitting covers or floating lids) should be used to prevent the release of potential air contaminants from storage and other tanks. A flexible exhaust may be attached to tank covers to facilitate the removal of volatile chemicals (see figure 4). As appropriate, automixers, which allow individual parts of multicomponent products to be added directly to and subsequently mixed in processors, should be used because they decrease the potential for operator exposure to photochemicals.

Figure 4. Chemical mixing tank exhaust

When mixing dry chemicals, the containers should be emptied gently to minimize chemical dust from becoming airborne. Tables, benches, shelves and ledges should be wiped with a water-dampened cloth frequently to keep residual chemical dust from accumulating and later becoming airborne.

Facility and operations design

Surfaces that may be contaminated with chemicals should be constructed to permit flushing with water. Adequate provisions should be made for floor drains, particularly in storage, mixing and processing areas. Because of the potential for leaks or spills, arrangements should be made for containment, neutralization and proper disposal of photochemicals. Since floors may be wet at times, flooring around potentially wet areas should be covered with non-skid tape or paint for safety purposes. Consideration should also be given to potential electrical hazards. For electrical devices used in or near water, ground-fault circuit interrupters and appropriate grounding should be used.

As a general rule, photochemicals should be stored in a cool (at temperatures no lower than 4.4 °C), dry (relative humidity between 35 and 50%), well-ventilated area, where they can be easily inventoried and retrieved. Chemical inventories should be actively managed so that the quantities of hazardous chemicals stored can be minimized and so that materials are not stored beyond their expiration dates. All containers should be properly labelled.

Chemicals should be stored to minimize the likelihood of container breakage during storage and retrieval. Chemical containers should not be stored where they can fall over, above eye level or where personnel have to stretch to reach them. Most hazardous materials should be stored at a low level and on a firm base in order to avoid possible breakage and spilling on the skin or eyes. Chemicals that, if accidentally mixed, might lead to fire, explosion or toxic chemical release should be segregated. For example, strong acids, strong bases, reducers, oxidizers and organic chemicals should be stored separately.

Flammable and combustible liquids should be stored in approved containers and storage cabinets. Storage areas should be kept cool, and smoking, open flames, heaters or anything else that might cause accidental ignition should be prohibited. During transfer operations, it should be ensured that containers are properly bonded and grounded. The design and operation of storage and handling areas for flammable and combustible materials should comply with applicable fire and electrical codes.

Whenever possible, solvents and liquids should be dispensed by metering pumps rather than by pouring. Pipetting of concentrated solutions and establishing siphons by mouth should not be permitted. The use of pre-weighed or pre-measured preparations may simplify operations and reduce the opportunities for accidents. Careful maintenance of all pumps and lines is necessary to avoid leakage.

Good personal hygiene should always be practiced in photoprocessing areas. Chemicals should never be placed in beverage or food containers or vice versa; only containers intended for chemicals should be used. Food or drink should never be brought into areas where chemicals are used, and chemicals should not be stored in refrigerators used for food. After handling chemicals, hands should be washed thoroughly, especially before eating or drinking.

Training and education

All personnel, including maintenance and housekeeping, should be trained in safety procedures relevant to their job tasks. An education programme for all personnel is essential in promoting safe work practices and preventing accidents. The educational programme should be carried out before personnel are allowed to work, at regular intervals thereafter and whenever new potential hazards are introduced into the workplace.

Summary

The key to working safely with photoprocessing chemicals is to understand the potential hazards of exposure and to manage the risk to an acceptable level. Risk management strategies for controlling potential occupational hazards in photoprocessing should include:

- providing personnel with training on potential hazards and safety procedures in the workplace,

- encouraging personnel to read and understand hazard communication vehicles (e.g., safety data sheets and product labels),

- maintaining workplace cleanliness and good personal hygiene,

- making certain that processors and other equipment are installed, operated and maintained to manufacturers’ specifications,

- substituting with less hazardous or less odorous chemicals, where possible,

- using engineering controls (e.g., general and local exhaust ventilation systems) where applicable,

- using protective equipment (e.g., protective gloves, goggles or face shield) when necessary,

- establishing procedures to ensure prompt medical attention for anyone with evidence of injury, and

- consideration of environmental exposure monitoring and health monitoring of employees as a verification of effective risk management strategies.

Additional information on black-and-white processing is discussed in the Entertainment and the arts chapter.

Overview of Environmental Issues

Major Environmental Issues

Solvents

Organic solvents are used for a number of applications in the printing industry. Major uses include cleaning solvents for presses and other equipment, solubilizing agents in inks, and additives in fountain solutions. In addition to general concerns about volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, some potential solvent components may be persistent in the environment or have high ozone-depleting potential.

Silver

During black-and-white and colour photographic processing, silver is released into some of the processing solutions. It is important to understand the environmental toxicology of silver so that these solutions can be properly handled and disposed of. While free silver ion is highly toxic to aquatic life, its toxicity is much lower in a complexed form as in photoprocessing effluent. Silver chloride, silver thiosulphate and silver sulphide, which are forms of silver commonly observed in photoprocessing, are over four orders of magnitude less toxic than silver nitrate. Silver has a high affinity for organic material, mud, clay and other matter found in natural environments, and this lessens its potential impact in aquatic systems. Given the extremely low level of free silver ion found in photoprocessing effluents or in natural waters, control technology appropriate to complexed silver is sufficiently protective of the environment.

Other photoprocessing effluent characteristics

The composition of photographic effluent varies, depending on the processes being run: black-and-white, colour reversal, colour negative/positive or some combination of these. Water comprises 90 to 99% of the effluent volume, with the majority of the remainder being inorganic salts that function as buffers and fixing (silver halide-solubilizing) agents, iron chelates, such as FeEthylene diamine tetra-acetic acid, and organic molecules that serve as developing agents and anti-oxidants. Iron and silver are the significant metals present.

Solid waste

Every component of the printing, photography and reproduction industries generates solid waste. This can consist of packaging waste such as cardboard and plastics, consumables such as toner cartridges or waste material from operations such as scrap paper or film. Increasing pressure on industrial generators of solid waste has led businesses to examine carefully options to lower solid waste through reduction, reuse or recycling.

Equipment

Equipment plays an obvious role in determining the environmental impact of the processes used in the printing, photography and reproduction industries. Beyond this, scrutiny is increasing on other aspects of equipment. One example is energy efficiency, which relates back to the environmental impact of the energy generation. Another example is “takeback legislation”, which requires the manufacturers to receive equipment back for proper disposal after its useful commercial life.

Control Technologies

The effectiveness of a given control methodology can be quite dependent on the specific operating processes of a facility, the size of that facility and the necessary level of control.

Solvent control technologies

Solvent use can be reduced in several ways. More volatile components, such as isopropyl alcohol, can be replaced with compounds having lower vapour pressure. In some situations, solvent-based inks and washes can be replaced with water-based materials. Many printing applications need improvements in water-based options to compete effectively with solvent-based materials. High-solids ink technology can also result in reduction of organic solvent use.

Solvent emissions can be lowered by reducing the temperature of dampening or fountain solutions. In limited applications, solvents can be captured on adsorptive materials such as activated carbon, and reused. In other instances, windows of operation are too strict to allow captured solvents to be reused directly, but they may be recaptured for recycling offsite. Solvent emissions may be concentrated in condenser systems. These systems consist of heat exchangers followed by a filter or electrostatic precipitator. The condensate passes through an oil-water separator before ultimate disposal.

In larger operations, incinerators (sometimes called afterburners) can be used to destroy emitted solvents. Platinum or other precious metal materials may be used to catalyze the thermal process. Non-catalyzed systems must operate at higher temperatures but are not sensitive to processes that can poison catalysts. Heat recovery is generally necessary to make non-catalyzed systems cost effective.

Silver recovery technologies

The level of silver recovery from photoeffluent is controlled by the economics of recovery and/or by solution discharge regulations. Major silver recovery techniques include electrolysis, precipitation, metallic replacement and ion exchange.

In electrolytic recovery, current is passed through the silver-bearing solution and silver metal is plated on the cathode, usually a stainless steel plate. The silver flake is harvested by flexing, chipping or scraping and sent to a refiner for reuse. Attempting to lower the residual solution silver level significantly below 200 mg/l is inefficient and can result in formation of undesired silver sulphide or noxious sulphurous byproducts. Packed-bed cells are capable of reducing silver to lower levels but are more complex and expensive than cells with two-dimensional electrodes.

Silver may be recovered from solution by precipitation with some material that forms an insoluble silver salt. The most common precipitating agents are trisodium trimercaptotriazine (TMT) and various sulphide salts. If a sulphide salt is used, care must be taken to avoid generation of highly toxic hydrogen sulphide. TMT is an inherently safer alternative recently introduced to the photoprocessing industry. Precipitation has a recovery efficiency of greater than 99%.

Metallic replacement cartridges (MRCs) allow the flow of the silver-bearing solution over a filamentous deposit of iron metal. Silver ion is reduced to silver metal as iron is oxidized to ionic soluble species. The metallic silver sludge settles to the bottom of the cartridge. MRCs are not appropriate in areas where iron in the effluent is a concern. This method has a recovery efficiency of greater than 95%.

In ion exchange, anionic silver thiosulphate complexes exchange with other anions on a resin bed. When the capacity of the resin bed is exhausted, additional capacity is regenerated by stripping the silver with a concentrated thiosulphate solution or converting the silver to silver sulphide under acidic conditions. Under well-controlled conditions, this technique can lower silver below 1 mg/l. However, ion-exchange can be used only on solutions dilute in silver and thiosulphate. The column is extremely sensitive to stripping if the thiosulphate concentration of the influent is too high. Also, the technique is very labour- and equipment-intensive, making it expensive in practice.

Other photoeffluent control technologies

The most cost-efficient method to handle photographic effluent is via biological treatment at a secondary waste treatment plant (often referred to as a publicly owned treatment works, or POTW). Several constituents or parameters of photographic effluent may be regulated by sewer discharge permits. In addition to silver, other common regulated parameters include pH, chemical oxygen demand, biological oxygen demand and total dissolved solids. Multiple studies have demonstrated that photoprocessing wastes (including the small amount of silver remaining after reasonable silver recovery) following biological treatment are not expected to have an adverse effect on the receiving waters.

Other technologies have been applied to photoprocessing wastes. Haul-away for treatment in incinerators, cement kilns or other ultimate disposal is practised in some regions of the world. Some laboratories reduce the volume of solution to be hauled away through evaporation or distillation. Other oxidative techniques such as ozonation, electrolysis, chemical oxidation and wet air oxidation have been applied to photoprocessing effluents.

Another major source of reduced environmental burden is through source reduction. The level of silver coated per square metre in sensitized goods is steadily decreasing as new generations of products enter the marketplace. As the silver levels in media decrease, the amount of chemicals necessary to process a given area of film or paper has also decreased. Regeneration and reuse of solution overflows have also resulted in less environmental burden per image. For example, the amount of colour developing agent required to process a square metre of colour paper in 1996 is less than 20% of that required in 1980.

Solid-waste minimization

The desire to minimize solid waste is encouraging efforts to recycle and reuse materials rather than dispose of them in landfills. Recycling programmes exist for toner cartridges, film cassettes, single-use cameras and so on. Recycling and reuse of packaging is becoming more prevalent as well. More packaging and equipment parts are being labelled appropriately to allow more efficient material recycling programmes.

Life cycle analysis design for the environment

All of the issues discussed above have resulted in increasing consideration of the entire life cycle of a product, from procuring of natural resources to creating the products, to dealing with end-of-life issues for these products. Two related analytic tools, life cycle analysis and design for the environment, are being used to incorporate environmental issues into the decision-making process in product design, development and sales. Life cycle analysis takes into consideration all of the inputs and material flows for a product or process and attempts to quantitatively measure the impact on the environment of different options. Design for the environment brings into consideration various aspects of product design such as recyclability, reworkability and so on to minimize the impact on the environment of the production or disposal of the equipment in question.

Health Issues and Disease Patterns

Interpreting the human health data in the printing, commercial photographic processing and reproduction industry is no simple matter, since the processes are complex and are continually evolving - sometimes dramatically. While the use of automation has substantially reduced manual work exposures in modernized versions of all three of the disciplines, work volume per employee has increased substantially. Furthermore, dermal exposure represents an important route of exposure for these industries, yet is less well characterized by available industrial hygiene data. Case reporting of the less serious, reversible effects (e.g., headaches, nose and eye irritation) is incomplete and under-reported in the published literature. Despite these challenges and limitations, epidemiological studies, health surveys and case reports provide a substantial amount of information regarding the health status of workers in these industries.

Printing Activities

Agents and exposures

Today there are five categories of printing processes: flexography, gravure, letterpress, lithography and screen printing. The type of exposure that can occur from each process is related to the types of printing inks that are used and to the likelihood of inhalation (mists, solvent fumes and so on) and penetrable skin contact from the process and cleaning activities employed. It should be noted that the inks are composed of organic or inorganic pigments, oil or solvent vehicles (i.e., carriers), and additives applied for special printing purposes. Table 1 outlines some characteristics of different printing processes.

Table 1. Some potential exposures in the printing industry

|

Process |

Type of ink |

Solvent |

Potential exposures |

|

Flexography and gravure |

Liquid inks (low viscosity) |

Volatiles |

Organic solvents: xylene, benzene |

|

Letterpress and lithography |

Paste inks (high viscosity) |

Oils— |

Ink mist: hydrocarbon solvents; isopropanol; polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) |

|

Screen printing |

Semipaste |

Volatiles |

Organic solvents: xylene, cyclohexanone, butyl acetate |

Mortality and chronic risks

Several epidemiological and case-report studies exist on printers. Exposure characterizations are not quantified in much of the older literature. However, respirable-size carbon black particles with potentially carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (benzo(a)pyrene) bound to the surface have been reported in rotary letterpress printing machine rooms of newspaper production. Animal studies find the benzo(a)pyrene tightly bound to the surface of the carbon black particle and not easily released to lung or other tissues. This lack of “bioavailability” makes it more difficult to determine whether cancer risks are feasible. Several, but not all, cohort (i.e., populations followed through time) epidemiological studies have found suggestions of increased lung cancer rates in printers (table 2). A more detailed assessment of over 100 lung cancer cases and 300 controls (case-control type study) from a group of over 9,000 printing workers in Manchester, England (Leon, Thomas and Hutchings 1994) found that the duration of work in a machine room was related to lung cancer occurrence in rotary letterpress workers. Since smoking patterns of the workers are not known, direct consideration of the role of occupation in the study is unknown. However, it is suggestive that rotary letterpress work may have presented a lung cancer risk in previous decades. In some areas of the world, however, older technologies, such as rotary letterpress work, may still exist and thus afford opportunities for preventive assessments, as well as installation of appropriate controls where needed.

Table 2. Cohort studies of printing trade mortality risks

|

Population studied |

Number of workers |

Mortality risks* (95% C.I.) |

||||

|

Follow-up period |

Country |

All causes |

All cancers |

Lung cancer |

||

|

Newspaper pressmen |

1,361 |

(1949–65) – 1978 |

USA |

1.0 (0.8–1.0) |

1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

1.5 (0.9–2.3) |

|

Newspaper pressmen |

,700 |

(1940–55) – 1975 |

Italy |

1.1 (0.9–1.2) |

1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

1.5 (0.8–2.5) |

|

Typographers |

1,309 |

1961–1984 |

USA |

0.7 (0.7–0.8) |

0.8 (0.7–1.0) |

0.9 (0.6–1.2) |

|

Printers (NGA) |

4,702 |

(1943–63) – 1983 |

UK |

0.8 (0.7–0.8) |

0.7 (0.6–0.8) |

0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

|

Printers (NATSOPA) |

4,530 |

(1943–63) – 1983 |

UK |

0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

|

Rotogravure |

1,020 |

(1925–85) – 1986 |

Sweden |

1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

1.4 (1.0–1.9) |

1.4 (0.7–2.5) |

|

Paperboard printers |

2,050 |

(1957–88) – 1988 |

USA |

1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

0.6 (0.3–0.9) |

0.5 (0.2–1.2) |

* Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR) = number of observed deaths divided by number of expected deaths, adjusted for age effects over the time periods in question. An SMR of 1 indicates no difference between observed and expected. Note: 95% confidence intervals are provided for the SMRs.

NGA = National Graphical Association, UK

NATSOPA = National Society of Operative Printers, Graphical and Media Personnel, UK.

Sources: Paganini-Hill et al. 1980; Bertazzi and Zoccheti 1980; Michaels, Zoloth and Stern 1991; Leon 1994; Svensson et al. 1990; Sinks et al. 1992.

Another group of workers that has been substantially studied are lithographers. Modern lithographers’ exposure to organic solvents (turpentine, toluene and so on), pigments, dyes, hydroquinone, chromates and cyanates has been markedly reduced in recent decades due to the use of computer technologies, automated processes and changes in materials. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recently concluded that occupational exposures in printing process are possibly carcinogenic to humans (IARC 1996). At the same time, it may be important to point out that IARC’s conclusion is based on historical exposures which, in most cases, should be significantly different today. Reports of malignant melanoma have suggested risks about twice the expected rate (Dubrow 1986). While some postulate that skin contact with hydroquinone could be related to melanoma (Nielson, Henriksen and Olsen 1996), it has not been confirmed in a hydroquinone manufacturing plant where significant exposure to hydroquinone was reported (Pifer et al. 1995). However, practices which minimize skin contact with solvents, particularly in plate cleaning, should be emphasized.

Photographic Processing Activities

Exposures and agents

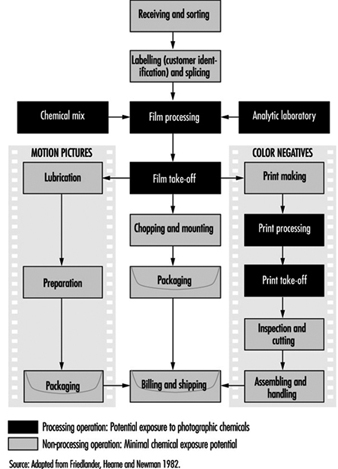

Photographic processing of black-and-white or colour film or paper can be done either manually or by essentially fully automated larger-scale processes. The selection of the process, chemicals, working conditions (including ventilation, hygiene and personal protective equipment) and workload can all influence the types of exposures and potential health issues of the occupational environment. The types of jobs (i.e., processor-related tasks) having the greatest potential for exposure to key photographic chemicals, such as formaldehyde, ammonia, hydroquinone, acetic acid and colour developers, are noted in table 3. The typical photographic processing and handling work flow is depicted in figure 1.

Table 3. Tasks in photographic processing with chemical exposure potential

|

Work area |

Tasks with exposure potential |

|

Chemical mixing |

Mix chemicals into solution. |

|

Analytical laboratory |

Handle samples. |

|

Film/print processing |

Process film and print using developers, hardeners, bleaches. |

|

Film/print take-off |

Remove processed film and prints for drying. |

Figure 1. Photographic processing operations

In more recently designed high-volume processing units, some of the steps in the workflow have been combined and automated, making inhalation and skin contact less likely. Formaldehyde, an agent that has been used for decades as a colour image stabilizer, is diminishing in concentration in photographic product. Depending on the specific process and site environmental conditions, its air concentration may range from non-detectable levels in the operator’s breathing zone up to about 0.2 ppm at machine dryer vents. Exposures can also occur during equipment cleaning, making or replenishing stabilizer fluid and unloading processors, as well as in spill situations.

It should be noted that while chemical exposures have been the primary focus of most health studies of photographic processors, other work environmental aspects, such as reduced light, materials handling and the postural demands of the job, are also of preventive health interest.

Mortality risks

The only published mortality surveillance of photographic processors suggests no increased risks of death for the occupation (Friedlander, Hearne and Newman 1982). The study covered nine processing laboratories in the United States, and was updated to cover 15 more years of follow-up (Pifer 1995). It should be noted that this is a study of over 2,000 employees who were actively working at the beginning of 1964, with over 70% of them having had at least 15 years of employment in their profession at that time. The group was followed for 31 years, through 1994. Many exposures relevant earlier in the careers of these employees, such as carbon tetrachloride, n-butylamine, and isopropylamine, were discontinued in the laboratories over thirty years ago. However, many of the key exposures in modern laboratories (i.e., acetic acid, formaldehyde and sulphur dioxide) were also present in previous decades, albeit at much higher concentrations. During the 31-year follow-up time period, the standardized mortality ratio was only 78% of that expected (SMR 0.78), with 677 deaths in the 2,061 workers. No individual causes of death were significantly increased.

The 464 processors in the study also had reduced mortality, whether compared to the general population (SMR 0.73) or to other hourly workers (SMR 0.83) and had no significant increases in any cause of death. Based on available epidemiological information, it does not appear that photographic processing presents an increased mortality risk, even at the higher concentrations of exposure likely to have been present in the 1950s and 1960s.

Pulmonary disease

The literature has very few reports of pulmonary disorders for photographic processors. Two articles, (Kipen and Lerman 1986; Hodgson and Parkinson 1986) describe a total of four potential pulmonary responses to processing workplace exposures; however, neither had quantitative environmental exposure data to assess the measured pulmonary findings. No increases in longer-term illness absence for pulmonary disorders was identified in the only epidemiological review of the subject (Friedlander, Hearne and Newman 1982); however, it is important to note that illness-absences of eight consecutive days were required in order to be captured in that study. It appears that respiratory symptoms can be aggravated or initiated in sensitive individuals by exposure to higher concentrations of acetic acid, sulphur dioxide and other agents in photographic processing, should ventilation be poorly controlled or errors occur during mixing, resulting in the release of undesired concentrations of these agents. However, work-related pulmonary cases have only rarely been reported in this occupation (Hodgson and Parkinson 1986).

Acute and subchronic effects

Contact irritative and allergic dermatitis has been reported in photographic processors for decades, starting with the initial use of colour chemicals in the late 1930s. Many of these cases occurred in the first few months of a processor’s exposure. The use of protective gloves and improved handling processes have substantially reduced photographic dermatitis. Eyesplashes with some photochemicals can present risks of corneal injury. Training on eyewash procedures (flushing eyes with cool water for at least 15 minutes followed by medical attention) and the use of protective eyewear is particularly important for photoprocessors, many of whom may work in isolation and/or in diminished light environments.

Some ergonomics concerns exist regarding the operation of rapid-turnaround, high-volume photographic processing units. The mounting and dismounting of large rolls of photographic paper can present a risk of upper back, shoulder and neck disorders. The rolls can weigh 13.6 to 22.7 kg (30 to 50 pounds), and may be awkward to handle, depending partly on access to the machine, which can be compromised in compact work sites.

Injuries and strains to the staff can be prevented by proper staff training, by provision of adequate access to the rolls and by considerations of human factors in the general design of the processing area.

Prevention and methods of early detection of effects

Protection from dermatitis, respiratory irritation, acute injury and ergonomic disorders starts with the recognition that such disorders can occur. With proper worker information (including labels, material safety data sheets, protective equipment and health protection training programmes), periodic health/safety reviews of the worksetting and informed supervision, prevention can be strongly emphasized. In addition, the early identification of disorders can be facilitated by having a medical resource for worker health reporting, coupled with targeted voluntary periodic health assessments, focusing on respiratory and upper extremity symptoms in questionnaires and direct observation of exposed skin areas for signs of work-related dermatitis.