Radiation Accidents

Description, Sources, Mechanisms

Apart from the transportation of radioactive materials, there are three settings in which radiation accidents can occur:

- use of nuclear reactions to produce energy or arms, or for research purposes

- industrial applications of radiation (gamma radiography, irradiation)

- research and nuclear medicine (diagnosis or therapy).

Radiation accidents may be classified into two groups on the basis of whether or not there is environmental emission or dispersion of radionuclides; each of these types of accident affects different populations.

The magnitude and duration of the exposure risk for the general population depends on the quantity and the characteristics (half-life, physical and chemical properties) of the radionuclides emitted into the environment (table 1). This type of contamination occurs when there is rupture of the containment barriers at nuclear power plants or industrial or medical sites which separate radioactive materials from the environment. In the absence of environmental emissions, only workers present onsite or handling radioactive equipment or materials are exposed.

Table 1. Typical radionuclides, with their radioactive half-lives

|

Radionuclide |

Symbol |

Radiation emitted |

Physical half-life* |

Biological half-life |

|

Barium-133 |

Ba-133 |

γ |

10.7 y |

65 d |

|

Cerium-144 |

Ce-144 |

β,γ |

284 d |

263 d |

|

Caesium-137 |

Cs-137 |

β,γ |

30 y |

109 d |

|

Cobalt-60 |

Co-60 |

β,γ |

5.3 y |

1.6 y |

|

Iodine-131 |

I-131 |

β,γ |

8 d |

7.5 d |

|

Plutonium-239 |

Pu-239 |

α,γ |

24,065 y |

50 y |

|

Polonium-210 |

Po-210 |

α |

138 d |

27 d |

|

Strontium-90 |

Sr-90 |

β |

29.1 y |

18 y |

|

Tritium |

H-3 |

β |

12.3 y |

10 d |

* y = years; d = days.

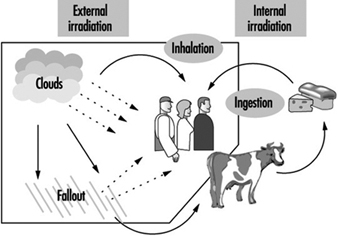

Exposure to ionizing radiation may occur through three routes, regardless of whether the target population is composed of workers or the general public: external irradiation, internal irradiation, and contamination of skin and wounds.

External irradiation occurs when individuals are exposed to an extracorporeal radiation source, either point (radiotherapy, irradiators) or diffuse (radioactive clouds and fallout from accidents, figure 1). Irradiation may be local, involving only a portion of the body, or whole body.

Figure 1. Exposure pathways to ionizing radiation after an accidental release of radioactivity in the environment

Internal radiation occurs following incorporation of radioactive substances into the body (figure 1) through either inhalation of airborne radioactive particles (e.g., caesium-137 and iodine-131, present in the Chernobyl cloud) or ingestion of radioactive materials in the food chain (e.g., iodine-131 in milk). Internal irradiation may affect the whole body or only certain organs, depending on the characteristics of the radionuclides: caesium-137 distributes itself homogeneously throughout the body, while iodine-131 and strontium-90 concentrate in the thyroid and the bones, respectively.

Finally, exposure may also occur through direct contact of radioactive materials with skin and wounds.

Accidents involving nuclear power plants

Sites included in this category include power-generating stations, experimental reactors, facilities for the production and processing or reprocessing of nuclear fuel and research laboratories. Military sites include plutonium breeder reactors and reactors located aboard ships and submarines.

Nuclear power plants

The capture of heat energy emitted by atomic fission is the basis for the production of electricity from nuclear energy. Schematically, nuclear power plants can be thought of as comprising: (1) a core, containing the fissile material (for pressurized-water reactors, 80 to 120 tonnes of uranium oxide); (2) heat-transfer equipment incorporating heat-transfer fluids; (3) equipment capable of transforming heat energy into electricity, similar to that found in power plants that are not nuclear.

Strong, sudden power surges capable of causing core meltdown with emission of radioactive products are the primary hazards at these installations. Three accidents involving reactor-core meltdown have occurred: at Three Mile Island (1979, Pennsylvania, United States), Chernobyl (1986, Ukraine), and Fukushima (2011, Japan) [Edited, 2011].

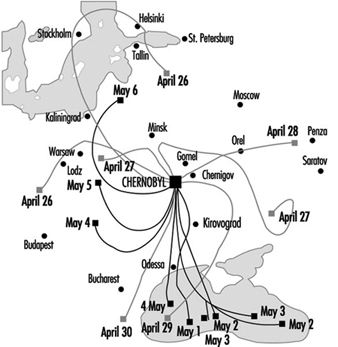

The Chernobyl accident was what is known as a criticality accident—that is, a sudden (within the space of a few seconds) increase in fission leading to a loss of process control. In this case, the reactor core was completely destroyed and massive amounts of radioactive materials were emitted (table 2). The emissions reached a height of 2 km, favouring their dispersion over long distances (for all intents and purposes, the entire Northern hemisphere). The behaviour of the radioactive cloud has proven difficult to analyse, due to meteorological changes during the emission period (figure 2) (IAEA 1991).

Table 2. Comparison of different nuclear accidents

|

Accident |

Type of facility |

Accident |

Total emitted |

Duration |

Main emitted |

Collective |

|

Khyshtym 1957 |

Storage of high- |

Chemical explosion |

740x106 |

Almost |

Strontium-90 |

2,500 |

|

Windscale 1957 |

Plutonium- |

Fire |

7.4x106 |

Approximately |

Iodine-131, polonium-210, |

2,000 |

|

Three Mile Island |

PWR industrial |

Coolant failure |

555 |

? |

Iodine-131 |

16–50 |

|

Chernobyl 1986 |

RBMK industrial |

Critically |

3,700x106 |

More than 10 days |

Iodine-131, iodine-132, |

600,000 |

|

Fukushima 2011

|

The final report of the Fukushima Assessment Task Force will be submitted in 2013. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: UNSCEAR 1993.

Figure 2. Trajectory of emissions from the Chernobyl accident, 26 April-6 May 1986

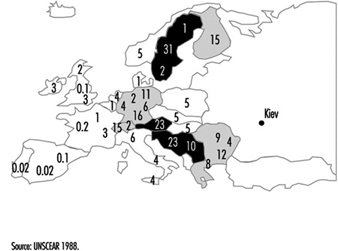

Contamination maps were drawn up on the basis of environmental measurements of caesium-137, one of the main radioactive emission products (table 1 and table 2). Areas of Ukraine, Byelorussia (Belarus) and Russia were heavily contaminated, while fallout in the rest of Europe was less significant (figure 3 and figure 4 (UNSCEAR 1988). Table 3 presents data on the area of the contaminated zones, characteristics of the exposed populations and routes of exposure.

FIgure 3. Caesium-137 deposition in Byelorussia, Russia and Ukraine following the Chernobyl accident.

Figure 4. Caesium-137 fallout (kBq/km2) in Europe following the Chernobyl accident

Table 3. Area of contaminated zones, types of populations exposed and modes of exposure in Ukraine, Byelorussia and Russia following the Chernobyl accident

|

Type of population |

Surface area ( km2 ) |

Population size (000) |

Main modes of exposure |

|

Occupationally exposed populations: |

|||

|

Employees onsite at |

≈0.44 |

External irradiation, |

|

|

General public: |

|||

|

Evacuated from the |

|

115 |

External irradiation by |

* Individuals participating in clean-up within 30 km of the site. These include fire-fighters, military personnel, technicians and engineers who intervened during the first weeks, as well as physicians and researchers active at a later date.

** Caesium-137 contamination.

Source: UNSCEAR 1988; IAEA 1991.

The Three Mile Island accident is classified as a thermal accident with no reactor runaway, and was the result of a reactor-core coolant failure lasting several hours. The containment shell ensured that only a limited quantity of radioactive material was emitted into the environment, despite the partial destruction of the reactor core (table 2). Although no evacuation order was issued, 200,000 residents voluntarily evacuated the area.

Finally, an accident involving a plutonium production reactor occurred on the west coast of England in 1957 (Windscale, table 2). This accident was caused by a fire in the reactor core and resulted in environmental emissions from a chimney 120 metres high.

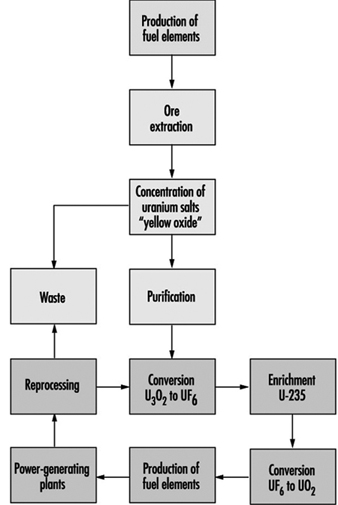

Fuel-processing facilities

Fuel production facilities are located “upstream” from nuclear reactors and are the site of ore extraction and the physical and chemical transformation of uranium into fissile material suitable for use in reactors (figure 5). The primary accident hazards present in these facilities are chemical in nature and related to the presence of uranium hexafluoride (UF6), a gaseous uranium compound which may decompose upon contact with air to produce hydrofluoric acid (HF), a very corrosive gas.

Figure 5. Nuclear fuel processing cycle.

“Downstream” facilities include fuel storage and reprocessing plants. Four criticality accidents have occurred during chemical reprocessing of enriched uranium or plutonium (Rodrigues 1987). In contrast to accidents occurring at nuclear power plants, these accidents involved small quantities of radioactive materials—tens of kilograms at most—and resulted in negligible mechanical effects and no environmental emission of radioactivity. Exposure was limited to very high dose, very short term (of the order of minutes) external gamma ray and neutron irradiation of workers.

In 1957, a tank containing highly radioactive waste exploded at Russia’s first military-grade plutonium production facility, located in Khyshtym, in the south Ural Mountains. Over 16,000 km2 were contaminated and 740 PBq (20 MCi) were emitted into the atmosphere (table 2 and table 4).

Table 4. Surface area of the contaminated zones and size of population exposed after the Khyshtym accident (Urals 1957), by strontium-90 contamination

|

Contamination ( kBq/m2 ) |

( Ci/km2 ) |

Area ( km2 ) |

Population |

|

≥ 37,000 |

≥ 1,000 |

20 |

1,240 |

|

≥ 3,700 |

≥100 |

120 |

1,500 |

|

≥ 74 |

≥ 2 |

1,000 |

10,000 |

|

≥ 3.7 |

≥ 0.1 |

15,000 |

270,000 |

Research reactors

Hazards at these facilities are similar to those present at nuclear power plants, but are less serious, given the lower power generation. Several criticality accidents involving significant irradiation of personnel have occurred (Rodrigues 1987).

Accidents related to the use of radioactive sources in industry and medicine (excluding nuclear plants) (Zerbib 1993)

The most common accident of this type is the loss of radioactive sources from industrial gamma radiography, used, for example, for the radiographic inspection of joints and welds. However, radioactive sources may also be lost from medical sources (table 5). In either case, two scenarios are possible: the source may be picked up and kept by a person for several hours (e.g., in a pocket), then reported and restored, or it may be collected and carried home. While the first scenario causes local burns, the second may result in long-term irradiation of several members of the general public.

Table 5. Accidents involving the loss of radioactive sources and which resulted in exposure of the general public

|

Country (year) |

Number of |

Number of |

Number of deaths** |

Radioactive material involved |

|

Mexico (1962) |

? |

5 |

4 |

Cobalt-60 |

|

China (1963) |

? |

6 |

2 |

Cobalt 60 |

|

Algeria (1978) |

22 |

5 |

1 |

Iridium-192 |

|

Morocco (1984) |

? |

11 |

8 |

Iridium-192 |

|

Mexico |

≈4,000 |

5 |

0 |

Cobalt-60 |

|

Brazil |

249 |

50 |

4 |

Caesium-137 |

|

China |

≈90 |

12 |

3 |

Cobalt-60 |

|

United States |

≈90 |

1 |

1 |

Iridium-192 |

* Individuals exposed to doses capable of causing acute or long-term effects or death.

** Among individuals receiving high doses.

Source: Nénot 1993.

The recovery of radioactive sources from radiotherapy equipment has resulted in several accidents involving the exposure of scrap workers. In two cases—the Juarez and Goiânia accidents—the general public was also exposed (see table 5 and box below).

The Goiвnia Accident, 1987

Between 21 September and 28 September 1987, several people suffering from vomiting, diarrhoea, vertigo and skin lesions at various parts of the body were admitted to the hospital specializing in tropical diseases in Goiânia, a city of one million inhabitants in the Brazilian state of Goias. These problems were attributed to a parasitic disease common in Brazil. On 28 September, the physician responsible for health surveillance in the city saw a woman who presented him with a bag containing debris from a device collected from an abandoned clinic, and a powder which emitted, according to the woman “a blue light”. Thinking that the device was probably x-ray equipment, the physician contacted his colleagues at the hospital for tropical diseases. The Goias Department of the Environment was notified, and the next day a physicist took measurements in the hygiene department’s yard, where the bag was stored overnight. Very high radioactivity levels were found. In subsequent investigations the source of radioactivity was identified as a caesium-137 source (total activity: approximately 50 TBq (1,375 Ci)) which had been contained within radiotherapy equipment used in a clinic abandoned since 1985. The protective housing surrounding the caesium had been disassembled on 10 September 1987 by two scrapyard workers and the caesium source, in powder form, removed. Both the caesium and the fragments of the contaminated housing were gradually dispersed throughout the city. Several people who had transported or handled the material, or who had simply come to see it (including parents, friends and neighbours) were contaminated. In all, over 100,000 people were examined, of whom 129 were very seriously contaminated; 50 were hospitalized (14 for medullary failure), and 4, including a 6-year-old girl, died. The accident had dramatic economic and social consequences for the entire city of Goiânia and the state of Goias: 1/1000 of the city’s surface area was contaminated, and the price of agricultural produce, rents, real estate, and land all fell. The inhabitants of the entire state suffered real discrimination.

Source: IAEA 1989a

The Juarez accident was discovered serendipitously (IAEA 1989b). On 16 January 1984, a truck entering the Los Alamos (New Mexico, United States) scientific laboratory loaded with steel bars triggered a radiation detector. Investigation revealed the presence of cobalt-60 in the bars and traced the cobalt-60 to a Mexican foundry. On January 21, a heavily contaminated scrapyard in Juarez was identified as the source of the radioactive material. Systematic monitoring of roads and highways by detectors resulted in the identification of a heavily contaminated truck. The ultimate radiation source was determined to be a radiotherapy device stored in a medical centre until December 1983, at which time it was disassembled and transported to the scrapyard. At the scrapyard, the protective housing surrounding the cobalt-60 was broken, freeing the cobalt pellets. Some of the pellets fell into the truck used to transport scrap, and others were dispersed throughout the scrapyard during subsequent operations, mixing with the other scrap.

Accidents involving the entry of workers into active industrial irradiators (e.g., those used to preserve food, sterilize medical products, or polymerize chemicals) have occurred. In all cases, these have been due to failure to follow safety procedures or to disconnected or defective safety systems and alarms. The dose levels of external irradiation to which workers in these accidents were exposed were high enough to cause death. Doses were received within a few seconds or minutes (table 6).

Table 6. Main accidents involving industrial irradiators

|

Site, date |

Equipment* |

Number of |

Exposure level |

Affected organs |

Dose received (Gy), |

Medical effects |

|

Forbach, August 1991 |

EA |

2 |

several deciGy/ |

Hands, head, trunk |

40, skin |

Burns affecting 25–60% of |

|

Maryland, December 1991 |

EA |

1 |

? |

Hands |

55, hands |

Bilateral finger amputation |

|

Viet nam, November 1992 |

EA |

1 |

1,000 Gy/minute |

Hands |

1.5, whole body |

Amputation of the right hand and a finger of the left hand |

|

Italy, May 1975 |

CI |

1 |

Several minutes |

Head, whole body |

8, bone marrow |

Death |

|

San Salvador, February 1989 |

CI |

3 |

? |

Whole body, legs, |

3–8, whole body |

2 leg amputations, 1 death |

|

Israel, June 1990 |

CI |

1 |

1 minute |

Head, whole body |

10–20 |

Death |

|

Belarus, October 1991 |

CI |

1 |

Several minutes |

Whole body |

10 |

Death |

* EA: electron accelerator CI: cobalt-60 irradiator.

Source: Zerbib 1993; Nénot 1993.

Finally, medical and scientific personnel preparing or handling radioactive sources may be exposed through skin and wound contamination or inhalation or ingestion of radioactive materials. It should be noted that this type of accident is also possible in nuclear power plants.

Public Health Aspects of the Problem

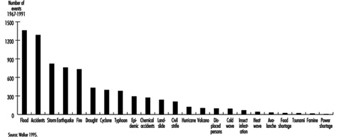

Temporal patterns

The United States Radiation Accident Registry (Oak Ridge, United States) is a worldwide registry of radiation accidents involving humans since 1944. To be included in the registry, an accident must have been the subject of a published report and have resulted in whole-body exposure exceeding 0.25 Sievert (Sv), or skin exposure exceeding 6 Sv or exposure of other tissues and organs exceeding 0.75 Sv (see "Case Study: What does dose mean?" for a definition of dose). Accidents that are of interest from the point of view of public health but which resulted in lower exposures are thus excluded (see below for a discussion of the consequences of exposure).

Analysis of the registry data from 1944 to 1988 reveals a clear increase in both the frequency of radiation accidents and the number of exposed individuals starting in 1980 (table 7). The increase in the number of exposed individuals is probably accounted for by the Chernobyl accident, particularly the approximately 135,000 individuals initially residing in the prohibited area within 30 km of the accident site. The Goiânia (Brazil) and Juarez (Mexico) accidents also occurred during this period and involved significant exposure of many people (table 5).

Table 7. Radiation accidents listed in the Oak Ridge (United States) accident registry (worldwide, 1944-88)

|

1944–79 |

1980–88 |

1944–88 |

|

|

Total number of accidents |

98 |

198 |

296 |

|

Number of individuals involved |

562 |

136,053 |

136,615 |

|

Number of individuals exposed to doses exceeding |

306 |

24,547 |

24,853 |

|

Number of deaths (acute effects) |

16 |

53 |

69 |

* 0.25 Sv for whole-body exposure, 6 Sv for skin exposure, 0.75 Sv for other tissues and organs.

Potentially exposed populations

From the point of view of exposure to ionizing radiation, there are two populations of interest: occupationally exposed populations and the general public. United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR 1993) estimates that 4 million workers worldwide were occupationally exposed to ionizing radiation in the period 1985-1989; of these, approximately 20% were employed in the production, use and processing of nuclear fuel (table 8). IAEA member countries were estimated to possess 760 irradiators in 1992, of which 600 were electron accelerators and 160 gamma irradiators.

Table 8. Temporal pattern of occupational exposure to ionizing radiation worldwide (in thousands)

|

Activity |

1975–79 |

1980–84 |

1985–89 |

|

Nuclear fuel processing* |

560 |

800 |

880 |

|

Military applications** |

310 |

350 |

380 |

|

Industrial applications |

530 |

690 |

560 |

|

Medical applications |

1,280 |

1,890 |

2,220 |

|

Total |

2,680 |

3,730 |

4,040 |

* Production and reprocessing of fuel: 40,000; reactor operation: 430,000.

** including 190,000 shipboard personnel.

Source: UNSCEAR 1993.

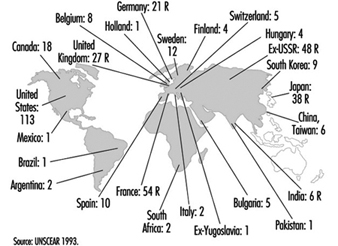

The number of nuclear sites per country is a good indicator of the potential for exposure of the general public (figure 6).

Figure 6. Distribution of power-generating reactors and fuel reprocessing plants in the world, 1989-90

Health Effects

Direct health effects of ionizing radiation

In general, the health effects of ionizing radiation are well known and depend on the dose level received and the dose rate (received dose per unit of time (see "Case Study: What does dose mean?").

Deterministic effects

These occur when the dose exceeds a given threshold and the dose rate is high. The severity of the effects is proportional to the dose, although the dose threshold is organ specific (table 9).

Table 9. Deterministic effects: thresholds for selected organs

|

Tissue or effect |

Equivalent single dose |

|

Testicles: |

|

|

Temporary sterility |

0.15 |

|

Permanent sterility |

3.5–6.0 |

|

Ovaries: |

|

|

Sterility |

2.5–6.0 |

|

Crystalline lens: |

|

|

Detectable opacities |

0.5–2.0 |

|

Impaired vision (cataracts) |

5.0 |

|

Bone marrow: |

|

|

Depression of haemopoiesis |

0.5 |

Source: ICRP 1991.

In the accidents such as those discussed above, deterministic effects may be caused by local intense irradiation, such as that caused by external irradiation, direct contact with a source (e.g., a misplaced source picked up and pocketed) or skin contamination. All these result in radiological burns. If the local dose is of the order of 20 to 25 Gy (table 6, "Case Study: What does dose mean?") tissue necrosis may ensue. A syndrome known as acute irradiation syndrome, characterized by digestive disorders (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) and bone marrow aplasia of variable severity, may be induced when the average whole-body irradiation dose exceeds 0.5 Gy. It should be recalled that whole-body and local irradiation may occur simultaneously.

Nine of 60 workers exposed during criticality accidents at nuclear fuel processing plants or research reactors died (Rodrigues 1987). Decedents received 3 to 45 Gy, while survivors received 0.1 to 7 Gy. The following effects were observed in survivors: acute irradiation syndrome (gastro-intestinal and haematological effects), bilateral cataracts and necrosis of limbs, requiring amputation.

At Chernobyl, power plant personnel, as well as emergency response personnel not using special protective equipment, suffered high beta and gamma radiation exposure in the initial hours or days following the accident. Five hundred people required hospitalization; 237 individuals who received whole-body irradiation exhibited acute irradiation syndrome, and 28 individuals died despite treatment (table 10) (UNSCEAR 1988). Others received local irradiation of the limbs, in some cases affecting over 50% of the body surface and continue to suffer, many years later, multiple skin disorders (Peter, Braun-Falco and Birioukov 1994).

Table 10. Distribution of patients exhibiting acute irradiation syndrome (AIS) after the Chernobyl accident, by severity of condition

|

Severity of AIS |

Equivalent dose |

Number of |

Number of |

Average survival |

|

I |

1–2 |

140 |

– |

– |

|

II |

2–4 |

55 |

1 (1.8) |

96 |

|

III |

4–6 |

21 |

7 (33.3) |

29.7 |

|

IV |

>6 |

21 |

20 (95.2) |

26.6 |

Source: UNSCEAR 1988.

Stochastic effects

These are probabilistic in nature (i.e., their frequency increases with received dose), but their severity is independent of dose. The main stochastic effects are:

- Mutation. This has been observed in animal experiments but has been difficult to document in humans.

- Cancer. The effect of irradiation on the risk of developing cancer has been studied in patients receiving radiation therapy and in survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. UNSCEAR (1988, 1994) regularly summarizes the results of these epidemiological studies. The duration of the latency period is typically 5 to 15 years from the date of exposure depending on organ and tissue. Table 11 lists the cancers for which an association with ionizing radiation has been established. Significant cancer excesses have been demonstrated among survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings with exposures above 0.2 Sv.

- Selected benign tumours. Benign thyroid adenomas.

Table 11. Results of epidemiological studies of the effect of high dose rate of external irradiation on cancer

|

Cancer site |

Hiroshima/Nagasaki |

Other studies |

|

|

Mortality |

Incidence |

||

|

Haematopoietic system |

|||

|

Leukaemia |

+* |

+* |

6/11 |

|

Lymphoma (not specified) |

+ |

0/3 |

|

|

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

+* |

1/1 |

|

|

Myeloma |

+ |

+ |

1/4 |

|

Oral cavity |

+ |

+ |

0/1 |

|

Salivary glands |

+* |

1/3 |

|

|

Digestive system |

|||

|

Oesophagus |

+* |

+ |

2/3 |

|

Stomach |

+* |

+* |

2/4 |

|

Small intestine |

1/2 |

||

|

Colon |

+* |

+* |

0/4 |

|

Rectum |

+ |

+ |

3/4 |

|

Liver |

+* |

+* |

0/3 |

|

Gall bladder |

0/2 |

||

|

Pancreas |

3/4 |

||

|

Respiratory system |

|||

|

Larynx |

0/1 |

||

|

Trachea, bronchi, lungs |

+* |

+* |

1/3 |

|

Skin |

|||

|

Not specified |

1/3 |

||

|

Melanoma |

0/1 |

||

|

Other cancers |

+* |

0/1 |

|

|

Breast (women) |

+* |

+* |

9/14 |

|

Reproductive system |

|||

|

Uterus (non-specific) |

+ |

+ |

2/3 |

|

Uterine body |

1/1 |

||

|

Ovaries |

+* |

+* |

2/3 |

|

Other (women) |

2/3 |

||

|

Prostate |

+ |

+ |

2/2 |

|

Urinary system |

|||

|

Bladder |

+* |

+* |

3/4 |

|

Kidneys |

0/3 |

||

|

Other |

0/1 |

||

|

Central nervous system |

+ |

+ |

2/4 |

|

Thyroid |

+* |

4/7 |

|

|

Bone |

2/6 |

||

|

Connective tissue |

0/4 |

||

|

All cancers, excluding leukaemias |

1/2 |

||

+ Cancer sites studied in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors.

* Positive association with ionizing radiation.

1 Cohort (incidence or mortality) or case-control studies.

Source: UNSCEAR 1994.

Two important points concerning the effects of ionizing radiation remain controversial.

Firstly, what are the effects of low-dose irradiation (below 0.2 Sv) and low dose rates? Most epidemiological studies have examined survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings or patients receiving radiation therapy—populations exposed over very short periods to relatively high doses—and estimates of the risk of developing cancer as a result of exposure to low doses and dose rates depends essentially on extrapolations from these populations. Several studies of nuclear power plant workers, exposed to low doses over several years, have reported cancer risks for leukaemia and other cancers that are compatible with extrapolations from high-exposure groups, but these results remain unconfirmed (UNSCEAR 1994; Cardis, Gilbert and Carpenter 1995).

Secondly, is there a threshold dose (i.e., a dose below which there is no effect)? This is currently unknown. Experimental studies have demonstrated that damage to genetic material (DNA) caused by spontaneous errors or environmental factors are constantly repaired. However, this repair is not always effective, and may result in malignant transformation of cells (UNSCEAR 1994).

Other effects

Finally, the possibility of teratogenic effects due to irradiation during pregnancy should be noted. Microcephaly and mental retardation have been observed in children born to female survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings who received irradiation of at least 0.1 Gy during the first trimester (Otake, Schull and Yoshimura 1989; Otake and Schull 1992). It is unknown whether these effects are deterministic or stochastic, although the data do suggest the existence of a threshold.

Effects observed following the Chernobyl accident

The Chernobyl accident is the most serious nuclear accident to have occurred to date. However, even now, ten years after the fact, not all the health effects on the most highly exposed populations have been accurately evaluated. There are several reasons for this:

- Some effects appear only many years after the date of exposure: for example, solid-tissue cancers typically take 10 to 15 years to appear.

- As some time elapsed between the accident and the commencement of epidemiological studies, some effects occurring in the initial period following the accident may not have been detected.

- Useful data for the quantification of the cancer risk were not always gathered in a timely fashion. This is particularly true for data necessary to estimate the exposure of the thyroid gland to radioactive iodides emitted during the incident (tellurium-132, iodine-133) (Williams et al. 1993).

- Finally, many initially exposed individuals subsequently left the contaminated zones and were probably lost for follow-up.

Workers. Currently, comprehensive information is unavailable for all the workers who were strongly irradiated in the first few days following the accident. Studies on the risk to clean-up and relief workers of developing leukaemia and solid-tissue cancers are in progress (see table 3). These studies face many obstacles. Regular follow-up of the health status of clean-up and relief workers is greatly hindered by the fact that many of them came from different parts of the ex-USSR and were redispatched after working on the Chernobyl site. Further, received dose must be estimated retrospectively, as there are no reliable data for this period.

General population. The only effect plausibly associated with ionizing radiation in this population to date is an increase, starting in 1989, of the incidence of thyroid cancer in children younger than 15 years. This was detected in Byelorussia (Belarus) in 1989, only three years after the incident, and has been confirmed by several expert groups (Williams et al. 1993). The increase was particularly noteworthy in the most heavily contaminated areas of Belarus, especially the Gomel region. While thyroid cancer was normally rare in children younger than 15 years, (annual incidence rate of 1 to 3 per million), its incidence increased tenfold on a national basis and twentyfold in the Gomel area (table 12, figure 7), (Stsjazhko et al. 1995). A tenfold increase of the incidence of thyroid cancer was subsequently reported in the five most heavily contaminated areas of Ukraine, and an increase in thyroid cancer was also reported in the Bryansk (Russia) region (table 12). An increase among adults is suspected but has not been confirmed. Systematic screening programmes undertaken in the contaminated regions allowed latent cancers present prior to the accident to be detected; ultrasonographic programmes capable of detecting thyroid cancers as small as a few millimetres were particularly helpful in this regard. The magnitude of the increase in incidence in children, taken together with the aggressiveness of the tumours and their rapid development, suggests that the observed increases in thyroid gland cancer are partially due to the accident.

Table 12. Temporal pattern of the incidence and total number of thyroid cancers in children in Belarus, Ukraine & Russia, 1981-94

|

Incidence* (/100,000) |

Number of cases |

|||

|

1981–85 |

1991–94 |

1981–85 |

1991–94 |

|

|

Belarus |

||||

|

Entire country |

0.3 |

3.06 |

3 |

333 |

|

Gomel area |

0.5 |

9.64 |

1 |

164 |

|

Ukraine |

||||

|

Entire country |

0.05 |

0.34 |

25 |

209 |

|

Five most heavily |

0.01 |

1.15 |

1 |

118 |

|

Russia |

||||

|

Entire country |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Bryansk and |

0 |

1.00 |

0 |

20 |

* Incidence: the ratio of the number of new cases of a disease during a given period to the size of the population studied in the same period.

Source: Stsjazhko et al. 1995.

Figure 7. Incidence of cancer of the thyroid in children younger than 15 years in Belarus

In the most heavily contaminated zones (e.g., the Gomel region), the thyroid doses were high, particularly among children (Williams et al. 1993). This is consistent with the significant iodine emissions associated with the accident and the fact that radioactive iodine will, in the absence of preventive measures, concentrate preferentially in the thyroid gland.

Exposure to radiation is a well-documented risk factor for thyroid cancer. Clear increases in the incidence of thyroid cancer have been observed in a dozen studies of children receiving radiation therapy to the head and neck. In most cases, the increase was clear ten to 15 years after exposure, but was detectable in some cases within three to seven years. On the other hand, the effects in children of internal irradiation by iodine-131 and by short half-life iodine isotopes are not well established (Shore 1992).

The precise magnitude and pattern of the increase in the coming years of the incidence of thyroid cancer in the most highly exposed populations should be studied. Epidemiological studies currently under way should help to quantify the association between the dose received by the thyroid gland and the risk of developing thyroid cancer, and to identify the role of other genetic and environmental risk factors. It should be noted that iodine deficiency is widespread in the affected regions.

An increase in the incidence of leukaemia, particularly juvenile leukaemia (since children are more sensitive to the effects of ionizing radiation), is to be expected among the most highly exposed members of the population within five to ten years of the accident. Although no such increase has yet been observed, the methodological weaknesses of the studies conducted to date prevent any definitive conclusions from being drawn.

Psychosocial effects

The occurrence of more or less severe chronic psychological problems following psychological trauma is well established and has been studied primarily in populations faced with environmental disasters such as floods, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. Post-traumatic stress is a severe, long-lasting and crippling condition (APA 1994).

Most of our knowledge on the effect of radiation accidents on psychological problems and stress is drawn from studies conducted in the wake of the Three Mile Island accident. In the year following the accident, immediate psychological effects were observed in the exposed population, and mothers of young children in particular exhibited increased sensitivity, anxiety and depression (Bromet et al. 1982). Further, an increase in depression and anxiety-related problems was observed in power-plant workers, compared to workers in another power plant (Bromet et al. 1982). In the following years (i.e., after the reopening of the power plant), approximately one-quarter of the surveyed population exhibited relatively significant psychological problems. There was no difference in the frequency of psychological problems in the rest of the survey population, compared to control populations (Dew and Bromet 1993). Psychological problems were more frequent among individuals living close to the power plant who were without a social support network, had a history of psychiatric problems, or who had evacuated their home at the time of the accident (Baum, Cohen and Hall 1993).

Studies are also under way among populations exposed during the Chernobyl accident and for whom stress appears to be an important public health issue (e.g., clean-up and relief workers and individuals living in a contaminated zone). For the moment, however, there are no reliable data on the nature, severity, frequency and distribution of psychological problems in the target populations. The factors that must be taken into account when evaluating the psychological and social consequences of the accident on residents of the contaminated zones include the harsh social and economic situation, the diversity of the available compensation systems, the effects of evacuation and resettlement (approximately 100,000 additional people were resettled in the years following the accident), and the effects of lifestyle limitations (e.g., modification of nutrition).

Principles of Prevention and Guidelines

Safety principles and guidelines

Industrial and medical use of radioactive sources

While it is true that the major radiation accidents reported have all occurred at nuclear power plants, the use of radioactive sources in other settings has nevertheless resulted in accidents with serious consequences for workers or the general public. The prevention of accidents such as these is essential, especially in light of the disappointing prognosis in cases of high-dose exposure. Prevention depends on proper worker training and on the maintenance of a comprehensive life-cycle inventory of radioactive sources which includes information on both the sources’ nature and location. The IAEA has established a series of safety guidelines and recommendations for the use of radioactive sources in industry, medicine and research (Safety Series No. 102). The principles in question are similar to those presented below for nuclear power plants.

Safety in nuclear power plants (IAEA Safety Series No. 75, INSAG-3)

The goal here is to protect both humans and the environment from the emission of radioactive materials under any circumstance. To this end, it is necessary to apply a variety of measures throughout the design, construction, operation and decommissioning of nuclear power plants.

The safety of nuclear power plants is fundamentally dependent on the “defence in depth” principle—that is, the redundancy of systems and devices designed to compensate for technical or human errors and deficiencies. Concretely, radioactive materials are separated from the environment by a series of successive barriers. In nuclear power production reactors, the last of these barriers is the containment structure (absent on the Chernobyl site but present at Three Mile Island). To avoid the breakdown of these barriers and to limit the consequences of breakdowns, the following three safety measures should be practised throughout the power plant’s operational life: control of the nuclear reaction, cooling of fuel, and containment of radioactive material.

Another essential safety principle is “operating experience analysis”—that is, using information gleaned from events, even minor ones, occurring at other sites to increase the safety of an existing site. Thus, analysis of the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents has resulted in the implementation of modifications designed to ensure that similar accidents do not occur elsewhere.

Finally, it should be noted that significant efforts have been expended to promote a culture of safety, that is, a culture that is continually responsive to safety concerns related to the plant’s organization, activities and practices, as well as to individual behaviour. To increase the visibility of incidents and accidents involving nuclear power plants, an international scale of nuclear events (INES), identical in principle to scales used to measure the severity of natural phenomena such as earthquakes and wind, has been developed (table 12). This scale is not however suitable for the evaluation of a site’s safety or for performing international comparisons.

Table 13. International scale of nuclear incidents

|

Level |

Offsite |

Onsite |

Protective structure |

|

7—Major accident |

Major emission, |

||

|

6—Serious accident |

Significant emission, |

||

|

5—Accident |

Limited emission, |

Serious damage to |

|

|

4—Accident |

Low emission, public |

Damage to reactors |

|

|

3—Serious incident |

Very low emission, |

Serious |

Accident barely avoided |

|

2—Incident |

Serious contamination |

Serious failures of safety measures |

|

|

1—Abnormality |

Abnormality beyond |

||

|

0—Disparity |

No significance from |

Principles of the protection of the general public from exposure to radiation

In cases involving the potential exposure of the general public, it may be necessary to apply protective measures designed to prevent or limit exposure to ionizing radiation; this is particularly important if deterministic effects are to be avoided. The first measures which should be applied in emergency are evacuation, sheltering and administration of stable iodine. Stable iodine should be distributed to exposed populations, since this will saturate the thyroid and inhibit its uptake of radioactive iodine. To be effective, however, thyroid saturation must occur before or soon after the start of exposure. Finally, temporary or permanent resettlement, decontamination, and control of agriculture and food may eventually be necessary.

Each of these countermeasures has its own “action level” (table 14), not to be confused with the ICRP dose limits for workers and the general public, developed to ensure adequate protection in cases of non-accidental exposure (ICRP 1991).

Table 14. Examples of generic intervention levels for protective measures for general population

|

Protective measure |

Intervention level (averted dose) |

|

Emergency |

|

|

Containment |

10 mSv |

|

Evacuation |

50 mSv |

|

Distribution of stable iodine |

100 mGy |

|

Delayed |

|

|

Temporary resettlement |

30 mSv in 30 days; 10 mSv in the next 30 days |

|

Permanent resettlement |

1 Sv lifetime |

Source: IAEA 1994.

Research Needs and Future Trends

Current safety research concentrates on improving the design of nuclear power-generating reactors—more specifically, on the reduction of the risk and effects of core meltdown.

The experience gained from previous accidents should lead to improvements in the therapeutic management of seriously irradiated individuals. Currently, the use of bone marrow cell growth factors (haematopoietic growth factors) in the treatment of radiation-induced medullary aplasia (developmental failure) is being investigated (Thierry et al. 1995).

The effects of low doses and dose rates of ionizing radiation remains unclear and needs to be clarified, both from a purely scientific point of view and for the purposes of establishing dose limits for the general public and for workers. Biological research is necessary to elucidate the carcinogenic mechanisms involved. The results of large-scale epidemiological studies, especially those currently under way on workers at nuclear power plants, should prove useful in improving the accuracy of cancer risk estimates for populations exposed to low doses or dose rates. Studies on populations which are or have been exposed to ionizing radiation due to accidents should help further our understanding of the effects of higher doses, often delivered at low dose rates.

The infrastructure (organization, equipment and tools) necessary for the timely collection of data essential for the evaluation of the health effects of radiation accidents must be in place well in advance of the accident.

Finally, extensive research is necessary to clarify the psychological and social effects of radiation accidents (e.g., the nature and frequency of, and risk factors for, pathological and non-pathological post-traumatic psychological reactions). This research is essential if the management of both occupationally and non-occupationally exposed populations is to be improved.

Transportation of Hazardous Material: Chemical and Radioactive

The industries and economies of nations depend, in part, on the large numbers of hazardous materials transported from the supplier to the user and, ultimately, to the waste disposer. Hazardous materials are transported by road, rail, water, air and pipeline. The vast majority reach their destination safely and without incident. The size and scope of the problem is illustrated by the petroleum industry. In the United Kingdom it distributes around 100 million tons of product every year by pipeline, rail, road and water. Approximately 10% of those employed by the UK chemical industry are involved in distribution (i.e., transport and warehousing).

A hazardous material can be defined as “a substance or material determined to be capable of posing an unreasonable risk to health, safety or property when transported”. “Unreasonable risk” covers a broad spectrum of health, fire and environmental considerations. These substances include explosives, flammable gases, toxic gases, highly flammable liquids, flammable liquids, flammable solids, substances which become dangerous when wet, oxidizing substances and toxic liquids.

The risks arise directly from a release, ignition, and so on, of the dangerous substance(s) being transported. Road and rail threats are those which could give rise to major accidents “which could affect both employees and members of the public”. These dangers can occur when materials are being loaded or unloaded or are en route. The population at risk is people living near the road or railway and the people in other road vehicles or trains who might become involved in a major accident. Areas of risk include temporary stopover points such as railway marshalling yards and lorry parking areas at motorway service points. Marine risks are those linked to ships entering or leaving ports and loading or discharging cargoes there; risks also arise from coastal and straits traffic and inland waterways.

The range of incidents which can occur in association with transport both while in transit and at fixed installations include chemical overheating, spillage, leakage, escape of vapour or gas, fire and explosion. Two of the principal events causing incidents are collision and fire. For road tankers other causes of release may be leaks from valves and from overfilling. Generally, for both road and rail vehicles, non-crash fires are much more frequent than crash fires. These transport-associated incidents can occur in rural, urban industrial and urban residential areas, and can involve both attended and unattended vehicles or trains. Only in the minority of cases is an accident the primary cause of the incident.

Emergency personnel should be aware of the possibility of human exposure and contamination by a hazardous substance in accidents involving railways and rail yards, roads and freight terminals, vessels (both ocean and inland based) and associated waterfront warehouses. Pipelines (both long distance and local utility distribution systems) can be a hazard if damage or leakage occurs, either in isolation or in association with other incidents. Transportation incidents are often more dangerous than those at fixed facilities. The materials involved may be unknown, warning signs may be obscured by rollover, smoke or debris, and knowledgeable operatives may be absent or casualties of the event. The number of people exposed depends on population density, both by day and night, on the proportions indoors and outdoors, and on the proportion who may be considered particularly vulnerable. In addition to the population who are normally in the area, personnel of the emergency services who attend the accident are also at risk. It is not uncommon in an incident involving transport of hazardous materials that a significant proportion of the casualties include such personnel.

In the 20-year period 1971 through 1990, about 15 people were killed on the roads of the United Kingdom because of dangerous chemicals, compared with the annual average of 5,000 persons every year in motor accidents. However, small quantities of dangerous goods can cause significant damage. International examples include:

- A plane crashed near Boston, USA, because of leaking nitric acid.

- Over 200 people were killed when a road tanker of propylene exploded over a campsite in Spain.

- In a rail accident involving 22 rail cars of chemicals in Mississauga, Canada, a tanker containing 90 tonnes of chlorine was ruptured and there was an explosion and a large fire. There were no fatalities, but 250,000 persons were evacuated.

- A rail collision alongside the motorway in Eccles, United Kingdom, resulted in three deaths and 68 injuries from the collision, but none from the resulting serious fire of the petroleum products being transported.

- A petrol tanker went out of control in Herrborn, Germany, burning down a large part of the town.

- In Peterborough, United Kingdom, a vehicle carrying explosives killed one person and almost destroyed an industrial centre.

- A petrol tanker exploded in Bangkok, Thailand, killing a large number of people.

The largest number of serious incidents have arisen with flammable gas or liquids (partially related to the volumes moved), with some incidents from toxic gases and toxic fumes (including products of combustion).

Studies in the UK have shown the following for road transport:

- frequency of accident while conveying hazardous materials: 0.12 x 10–6/km

- frequency of release while conveying hazardous materials: 0.027 x 10–6/km

- probability of a release given a traffic accident: 3.3%.

These events are not synonymous with hazardous material incidents involving vehicles, and may constitute only a small proportion of the latter. There is also the individuality of accidents involving the road transport of hazardous materials.

International agreements covering the transport of potentially hazardous materials include:

Regulations for the Safe Transport of Radioactive Material 1985 (as amended 1990): International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, 1990 (STI/PUB/866). Their purpose is to establish standards of safety which provide an acceptable level of control of the radiation hazards to persons, property and the environment that are associated with the transport of radioactive material.

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea 1974 (SOLAS 74). This sets basic safety standards for all passenger and cargo ships, including ships carrying hazardous bulk cargoes.

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 (MARPOL 73/78). This provides regulations for the prevention of pollution by oil, noxious liquid substances in bulk, pollutants in packaged form or in freight containers, portable tanks or road and rail wagons, sewage and garbage. Regulation requirements are amplified in the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code.

There is a substantial body of international regulation of the transportation of harmful substances by air, rail, road and sea (converted into national legislation in many countries). Most are based on standards sponsored by the United Nations, and cover the principles of identification, labelling, prevention and mitigation. The United Nations Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods has produced Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods. They are addressed to governments and international organizations concerned with the regulation of the transport of dangerous goods. Among other aspects, the recommendations cover principles of classification and definitions of classes, listing of the content of dangerous goods, general packing requirements, testing procedures, making, labelling or placarding, and transport documents. These recommendations—the “Orange Book”—do not have the force of law, but form the basis of all the international regulations. These regulations are generated by various organizations:

- the International Civil Aviation Organization: Technical Instructions for Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air (Tis)

- the International Maritime Organization: International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code (IMDG Code)

- the European Economic Community: The European Agreement Concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR)

- the Office of International Rail Transport: Regulations Concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Rail (RID).

The preparation of major emergency plans to deal with and mitigate the effects of a major accident involving dangerous substances is as much needed in the transportation field as for fixed installations. The planning task is made more difficult in that the location of an incident will not be known in advance, thus requiring flexible planning. The substances involved in a transport accident cannot be foreseen. Because of the nature of the incident a number of products may be mixed together at the scene, causing considerable problems to the emergency services. The incident may occur in an area which is highly urbanized, remote and rural, heavily industrialized, or commercialized. An added factor is the transient population who may be unknowingly involved in an event because the accident has caused a backlog of vehicles either on the public highway or where passenger trains are stopped in response to a rail incident.

There is therefore a necessity for the development of local and national plans to respond to such events. These must be simple, flexible and easily understood. As major transport accidents can occur in a multiplicity of locations the plan must be appropriate to all potential scenes. For the plan to work effectively at all times, and in both remote rural and heavily populated urban locales, all organizations contributing to the response must have the ability to maintain flexibility while conforming to the basic principles of the overall strategy.

The initial responders should obtain as much information as possible to try to identify the hazard involved. Whether the incident is a spillage, a fire, a toxic release, or a combination of these will determine responses. The national and international marking systems used to identify vehicles transporting hazardous substances and carrying hazardous packaged goods should be known to the emergency services, who should have access to one of the several national and international databases which can help to identify the hazard and the problems associated with it.

Rapid control of the incident is vital. The chain of command must be identified clearly. This may change during the course of the event from the emergency services through the police to the civil government of the affected area. The plan must be able to recognize the effect on the population, both those working in or resident in the potentially affected area and those who may be transients. Sources of expertise on public health matters should be mobilized to advise on both the immediate management of the incident and on the potential for longer-term direct health effects and indirect ones through the food chain. Contact points for obtaining advice on environmental pollution to water courses and so on, and the effect of weather conditions on the movement of gas clouds must be identified. Plans must identify the possibility of evacuation as one of the response measures.

However, the proposals must be flexible, as there may be a range of costs and benefits, both in incident management and in public health terms, which will have to be considered. The arrangements must outline clearly the policy with respect to keeping the media fully informed and the action being taken to mitigate the effects. The information must be accurate and timely, with the spokesperson being knowledgeable as to the overall response and having access to experts to respond to specialized queries. Poor media relations can disrupt the management of the event and lead to unfavourable and sometimes unjustified comments on the overall handling of the episode. Any plan must include adequate mock disaster drills. These enable the responders to and managers of an incident to learn each other’s personal and organizational strengths and weaknesses. Both table-top and physical exercises are required.

Although the literature dealing with chemical spills is extensive, only a minor part describes the ecological consequences. Most concern case studies. The descriptions of actual spills have focused on human health and safety problems, with ecological consequences described only in general terms. The chemicals enter the environment predominantly through the liquid phase. In only a few cases did accidents having ecological consequences also affect humans immediately, and the effects on the environment were not caused by identical chemicals or by identical release routes.

Controls to prevent risk to human health and life from the transport of hazardous materials include quantities carried, direction and control of means of transport, routing, as well as authority over interchange and concentration points and developments near such areas. Further research is required into risk criteria, quantification of risk, and risk equivalence. The United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive has developed a Major Incident Data Service (MHIDAS) as a database of major chemical incidents worldwide. It currently holds information on over 6,000 incidents.

Case Study: Transport of Hazardous Materials

An articulated road tanker carrying about 22,000 litres of toluene was travelling on a main arterial road which runs through Cleveland, UK. A car pulled into the path of the vehicle, and, as the truckdriver took evasive action, the tanker overturned. The manlids of all five compartments sprang open and toluene spilled on the roadway and ignited, resulting in a pool fire. Five cars travelling on the opposite carriageway were involved in the fire but all occupants escaped.

The fire brigade arrived within five minutes of being called. Burning liquid had entered the drains, and drain fires were evident approximately 400m from the main incident. The County Emergency Plan was put into action, with social services and public transport put on alert in case evacuation was needed. Initial action by the fire brigade concentrated on extinguishing car fires and searching for occupants. The next task was identifying an adequate water supply. A member of the chemical company’s safety team arrived to coordinate with the police and fire commanders. Also in attendance were staff from the ambulance service and the environmental health and water boards. Following consultation it was decided to permit the leaking toluene to burn rather than extinguish the fire and have the chemical emitting vapours. Police put out warnings over a four-hour period utilizing national and local radio, advising people to stay indoors and close their windows. The road was closed for eight hours. When the toluene fell below the level of the manlids, the fire was extinguished and the remaining toluene removed from the tanker. The incident was concluded approximately 13 hours after the accident.

Potential harm to humans existed from thermal radiation; to the environment, from air, soil and water pollution; and to the economy, from traffic disruption. The company plan which existed for such a transportation incident was activated within 15 minutes, with five persons in attendance. A county offsite plan existed and was instigated with a control centre coming into being involving police and the fire brigade. Concentration measurement but not dispersion prediction was performed. The fire brigade response involved over 50 persons and ten appliances, whose major actions were fire-fighting, washing down and spillage retention. Over 40 police officers were committed in traffic direction, warning the public, security and press control. The health service response encompassed two ambulances and two onsite medical staff. Local government reaction involved environmental health, transport and social services. The public were informed of the incident by loudspeakers, radio and word of mouth. The information focused on what to do, especially on sheltering indoors.

The outcome to humans was two admissions to a single hospital, a member of the public and a company employee, both injured in the crash. There was noticeable air pollution but only slight soil and water contamination. From an economic perspective there was major damage to the road and extensive traffic delays, but no loss of crops, livestock or production. Lessons learned included the value of rapid retrieval of information from the Chemdata system and the presence of a company technical expert enabling correct immediate action to be taken. The importance of joint press statements from responders was highlighted. Consideration needs to be given to the environmental impact of fire-fighting. If the fire had been fought in the initial stages, a considerable amount of contaminated liquid (firewater and toluene) potentially could have entered the drains, water supplies and soil.

Avalanches: Hazards and Protective Measures

Ever since people began to settle in mountainous regions, they have been exposed to the specific hazards associated with mountain living. Among the most treacherous hazards are avalanches and landslides, which have taken their toll of victims even up to the present day.

When the mountains are covered with several feet of snow in winter, under certain conditions, a mass of snow lying like a thick blanket on the steep slopes or mountain tops can become detached from the ground underneath and slide downhill under its own weight. This can result in huge quantities of snow hurtling down the most direct route and settling into the valleys below. The kinetic energy thus released produces dangerous avalanches, which sweep away, crush or bury everything in their path.

Avalanches can be divided into two categories according to the type and condition of the snow involved: dry snow or “dust” avalanches, and wet snow or “ground” avalanches. The former are dangerous because of the shock waves they set off, and the latter because of their sheer volume, due to the added moisture in the wet snow, flattening everything as the avalanche rolls downhill, often at high speeds, and sometimes carrying away sections of the subsoil.

Particularly dangerous situations can arise when the snow on large, exposed slopes on the windward side of the mountain is compacted by the wind. Then it often forms a cover, held together only on the surface, like a curtain suspended from above, and resting on a base that can produce the effect of ball-bearings. If a “cut” is made in such a cover (e.g., if a skier leaves a track across the slope), or if for any reason, this very thin cover is torn apart (e.g., by its own weight), then the whole expanse of snow can slide downhill like a board, usually developing into an avalanche as it progresses.

In the interior of the avalanche, enormous pressure can build up, which can carry off, smash or crush locomotives or entire buildings as though they were toys. That human beings have very little chance of surviving in such an inferno is obvious, bearing in mind that anyone who is not crushed to death is likely to die from suffocation or exposure. It is not surprising, therefore, in cases where people have been buried in avalanches, that, even if they are found immediately, about 20% of them are already dead.

The topography and vegetation of the area will cause the masses of snow to follow set routes as they come down to the valley. People living in the region know this from observation and tradition, and therefore keep away from these danger zones in the winter.

In earlier times, the only way to escape such dangers was to avoid exposing oneself to them. Farmhouses and settlements were built in places where topographical conditions were such that avalanches could not occur, or which years of experience had shown to be far removed from any known avalanche paths. People even avoided the mountain areas altogether during the danger period.

Forests on the upper slopes also afford considerable protection against such natural disasters, as they support the masses of snow in the threatened areas and can curb, halt or divert avalanches that have already started, provided they have not built up too much momentum.

Nevertheless, the history of mountainous countries is punctuated by repeated disasters caused by avalanches, which have taken, and still take, a heavy toll of life and property. On the one hand, the speed and momentum of the avalanche is often underestimated. On the other hand, avalanches will sometimes follow paths which, on the basis of centuries of experience, have not previously been considered to be avalanche paths. Certain unfavourable weather conditions, in conjunction with a particular quality of snow and the state of the ground underneath (e.g., damaged vegetation or erosion or loosening of the soil as a result of heavy rains) produce circumstances that can lead to one of those “disasters of the century”.

Whether an area is particularly exposed to the threat of an avalanche depends not only on prevailing weather conditions, but to an even greater extent on the stability of the snow cover, and on whether the area in question is situated in one of the usual avalanche paths or outlets. There are special maps showing areas where avalanches are known to have occurred or are likely to occur as a result of topographical features, especially the paths and outlets of frequently occurring avalanches. Building is prohibited in high-risk areas.

However, these precautionary measures are no longer sufficient today, as, despite the prohibition of building in particular areas, and all the information available on the dangers, increasing numbers of people are still attracted to picturesque mountain regions, causing more and more building even in areas known to be dangerous. In addition to this disregard or circumvention of building bans, one of the manifestations of the modern leisure society is that thousands of tourists go to the mountains for sport and recreation in winter, and to the very areas where avalanches are virtually pre-programmed. The ideal ski slope is steep, free of obstacles and should have a sufficiently thick carpet of snow—ideal conditions for the skier, but also for the snow to sweep down into the valley.

If, however, risks cannot be avoided or are to a certain extent consciously accepted as an unwelcome “side-effect” of the enjoyment gained from the sport, then it becomes necessary to develop ways and means of coping with these dangers in another manner.

To improve the chances of survival for people buried in avalanches, it is essential to provide well-organized rescue services, emergency telephones near the localities at risk and up-to-date information for the authorities and for tourists on the prevailing situation in dangerous areas. Early warning systems and excellent organization of rescue services with the best possible equipment can considerably increase chances of survival for people buried in avalanches, as well as reducing the extent of the damage.

Protective Measures

Various methods of protection against avalanches have been developed and tested all over the world, such as cross-frontier warning services, barriers and even the artificial triggering-off of avalanches by blasting or firing guns over the snow fields.

The stability of the snow cover is basically determined by the ratio of mechanical stress to density. This stability can vary considerably according to the type of stress (e.g., pressure, tension, shearing strain) within a geographical region (e.g., that part of the snow field where an avalanche might start). Contours, sunshine, winds, temperature and local disturbances in the structure of the snow cover—resulting from rocks, skiers, snowploughs or other vehicles—can also affect stability. Stability can therefore be reduced by deliberate local intervention such as blasting, or increased by the installation of additional supports or barriers. These measures, which can be of a permanent or temporary nature, are the two main methods used for protection against avalanches.

Permanent measures include effective and durable structures, support barriers in the areas where the avalanche might start, diversionary or braking barriers on the avalanche path, and blocking barriers in the avalanche outlet area. The object of temporary protective measures is to secure and stabilize the areas where an avalanche might start by deliberately triggering off smaller, limited avalanches to remove the dangerous quantities of snow in sections.

Support barriers artificially increase the stability of the snow cover in potential avalanche areas. Drift barriers, which prevent additional snow from being carried by the wind to the avalanche area, can reinforce the effect of support barriers. Diversionary and braking barriers on the avalanche path and blocking barriers in the avalanche outlet area can divert or slow down the descending mass of snow and shorten the outflow distance in front of the area to be protected. Support barriers are structures fixed in the ground, more or less perpendicular to the slope, which put up sufficient resistance to the descending mass of snow. They must form supports reaching up to the surface of the snow. Support barriers are usually arranged in several rows and must cover all parts of the terrain from which avalanches could, under various possible weather conditions, threaten the locality to be protected. Years of observation and snow measurement in the area are required in order to establish correct positioning, structure and dimensions.

The barriers must have a certain permeability to let minor avalanches and surface landslides flow through a number of barrier rows without getting larger or causing damage. If permeability is not sufficient, there is the danger that the snow will pile up behind the barriers, and subsequent avalanches will slide over them unimpeded, carrying further masses of snow with them.

Temporary measures, unlike the barriers, can also make it possible to reduce the danger for a certain length of time. These measures are based on the idea of setting off avalanches by artificial means. The threatening masses of snow are removed from the potential avalanche area by a number of small avalanches deliberately triggered off under supervision at selected, predetermined times. This considerably increases the stability of the snow cover remaining on the avalanche site, by at least reducing the risk of further and more dangerous avalanches for a limited period of time when the threat of avalanches is acute.

However, the size of these artificially produced avalanches cannot be determined in advance with any great degree of accuracy. Therefore, in order to keep the risk of accidents as low as possible, while these temporary measures are being carried out, the entire area to be affected by the artificial avalanche, from its starting point to where it finally comes to a halt, must be evacuated, closed off and checked beforehand.

The possible applications of the two methods of reducing hazards are fundamentally different. In general, it is better to use permanent methods to protect areas that are impossible or difficult to evacuate or close off, or where settlements or forests could be endangered even by controlled avalanches. On the other hand, roads, ski runs and ski slopes, which are easy to close off for short periods, are typical examples of areas in which temporary protective measures can be applied.

The various methods of artificially setting off avalanches involve a number of operations which also entail certain risks and, above all, require additional protective measures for persons assigned to carry out this work. The essential thing is to cause initial breaks by setting off artificial tremors (blasts). These will sufficiently reduce the stability of the snow cover to produce a snow-slip.

Blasting is especially suitable for releasing avalanches on steep slopes. It is usually possible to detach small sections of snow at intervals and thus avoid major avalanches, which take a long distance to run their course and can be extremely destructive. However, it is essential that the blasting operations be carried out at any time of day and in all types of weather, and this is not always possible. Methods of artificially producing avalanches by blasting differ considerably according to the means used to reach the area where the blasting is to take place.

Areas where avalanches are likely to start can be bombarded with grenades or rockets from safe positions, but this is successful (i.e., produces the avalanche) in only 20 to 30% of cases, as it is virtually impossible to determine and to hit the most effective target point with any accuracy from a distance, and also because the snow cover absorbs the shock of the explosion. Besides, shells may fail to go off.

Blasting with commercial explosives directly into the area where avalanches are likely to start is generally more successful. The most successful methods are those whereby the explosive is carried on stakes or cables over the part of the snow field where the avalanche is to start, and detonated at a height of 1.5 to 3 m above the snow cover.

Apart from the shelling of the slopes, three different methods have been developed for getting the explosive for the artificial production of avalanches to the actual location where the avalanche is to start:

- dynamite cableways

- blasting by hand

- throwing or lowering the explosive charge from helicopters.

The cableway is the surest and at the same time the safest method. With the help of a special small cableway, the dynamite cableway, the explosive charge is carried on a winding rope over the blasting location in the area of snow cover in which the avalanche is to start. With proper rope control and with the help of signals and markings, it is possible to steer accurately towards what are known from experience to be the most effective locations, and to get the charge to explode directly above them. The best results with respect to triggering off avalanches are achieved when the charge is detonated at the correct height above the snow cover. Since the cableway runs at a greater height above the ground, this requires the use of lowering devices. The explosive charge hangs from a string wound around the lowering device. The charge is lowered to the correct height above the site selected for the explosion with the help of a motor which unwinds the string. The use of dynamite cableways makes it possible to carry out the blasting from a safe position, even with poor visibility, by day or night.

Because of the good results obtained and the relatively low production costs, this method of setting off avalanches is used extensively in the entire Alpine region, a licence being required to operate dynamite cableways in most Alpine countries. In 1988, an intensive exchange of experience in this field took place between manufacturers, users and government representatives from the Austrian, Bavarian and Swiss Alpine areas. The information gained from this exchange of experience has been summarized in leaflets and legally binding regulations. These documents basically contain the technical safety standards for equipment and installations, and instructions on carrying out these operations safely. When preparing the explosive charge and operating the equipment, the blasting crew must be able to move as freely as possible around the various cableway controls and appliances. There must be safe and easily accessible footpaths to enable the crew to leave the site quickly in case of emergency. There must be safe access routes up to cableway supports and stations. In order to avoid failure to explode, two fuses and two detonators must be used for every charge.